Although over the past decade the management of invasive fungal infection has improved, considerable controversy persists regarding antifungal prophylaxis in solid organ transplant recipients.

AimsTo identify the key clinical knowledge and make by consensus the high level recommendations required for antifungal prophylaxis in solid organ transplant recipients.

MethodsSpanish prospective questionnaire, which measures consensus through the Delphi technique, was conducted anonymously and by e-mail with 30 national multidisciplinary experts, specialists in invasive fungal infections from six national scientific societies, including intensivists, anesthetists, microbiologists, pharmacologists and specialists in infectious diseases that responded to 12 questions prepared by the coordination group, after an exhaustive review of the literature in the last few years. The level of agreement achieved among experts in each of the categories should be equal to or greater than 70% in order to make a clinical recommendation. In a second term, after extracting the recommendations of the selected topics, a face-to-face meeting was held with more than 60 specialists who were asked to validate the pre-selected recommendations and derived algorithm.

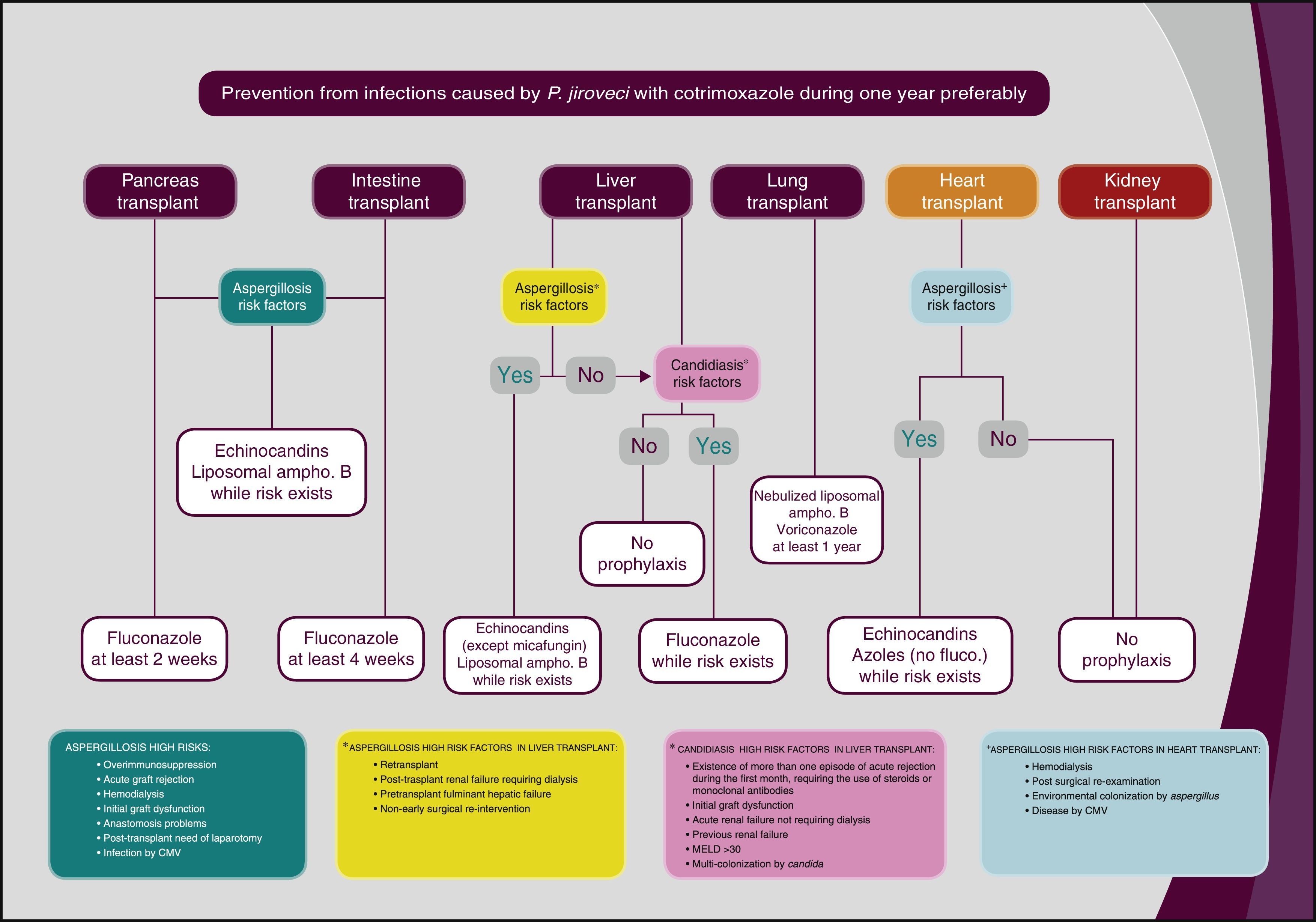

Measurements and primary outcomesEchinocandin antifungal prophylaxis should be considered in liver transplant with major risk factors (retransplantation, renal failure requiring dialysis after transplantation, pretransplant liver failure, not early reoperation, or MELD>30); heart transplant with hemodialysis, and surgical re-exploration after transplantation; environmental colonization by Aspergillus, or cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection; and pancreas and intestinal transplant in case of acute graft rejection, hemodialysis, initial graft dysfunction, post-perfusion pancreatitis with anastomotic problems or need for laparotomy after transplantation. Antifungal fluconazole prophylaxis should be considered in liver transplant without major risk factors and MELD 20–30, split or living donor, choledochojejunostomy, increased transfusion requirements, renal failure without replacement therapy, early reoperation, or multifocal colonization or infection with Candida; intestinal and pancreas transplant with no risk factors for echinocandin treatment. Liposomal amphotericin B antifungal prophylaxis should be considered in lung transplant (inhalant form) and liver transplant with major risk factors. Antifungal prophylaxis with voriconazole should be considered in lung transplant, and heart transplant with hemodialysis, surgical re-exploration after transplantation, environmental colonization by Aspergillus, or CMV infection.

ConclusionsThe management of antifungal prophylaxis in solid organ transplant recipients requires the application of knowledge and skills that are detailed in our recommendations and the algorithm developed therein. These recommendations, based on the DELPHI methodology, may help to identify potential patients, standardize their management and improve overall prognosis.

Aunque en la última década se ha observado una mejora en el tratamiento de la infección fúngica invasiva, todavía existen numerosas controversias en la profilaxis antifúngica del paciente trasplantado de órgano sólido.

ObjetivosIdentificar los principales conocimientos clínicos y elaborar recomendaciones con un alto nivel de consenso, necesarias para la profilaxis antifúngica del paciente trasplantado de órgano sólido.

MétodosSe realizó un cuestionario prospectivo español, que valora el consenso mediante la técnica Delphi. El cuestionario se llevó a cabo de forma anónima y por correo electrónico con 30 expertos multidisciplinarios nacionales, especialistas en infecciones fúngicas invasivas de seis sociedades científicas nacionales, que incluían intensivistas, anestesistas, microbiólogos, farmacólogos y especialistas en enfermedades infecciosas que respondieron a 12 preguntas preparadas por el grupo de coordinación, tras una revisión exhaustiva de la bibliografía de los últimos años. El nivel de acuerdo alcanzado entre los expertos en cada una de las categorías debía ser igual o superior al 70% para elaborar una recomendación. En un segundo término, después de extraer las recomendaciones de los temas seleccionados, se celebró una reunión presencial con más de 60 especialistas y se les solicitó la validación de las recomendaciones preseleccionadas y del algoritmo derivado de estas.

Mediciones y resultados principalesDebe considerarse la profilaxis antifúngica con equinocandinas en el trasplante hepático con los principales factores de riesgo (retrasplante, insuficiencia renal postrasplante con necesidad de diálisis, insuficiencia hepática pretrasplante, reintervención quirúrgica no precoz, o MELD>30); trasplante cardíaco con hemodiálisis, y reexploración quirúrgica postrasplante; colonización ambiental por Aspergillus, o infección por citomegalovirus; trasplante de páncreas e intestino si existe rechazo agudo del injerto, hemodiálisis, disfunción inicial del injerto, problemas en la anastomosis con pancreatitis posperfusión, o necesidad de laparotomía postrasplante. Debe considerarse la profilaxis antifúngica con fluconazol en el trasplante hepático sin los principales factores de riesgo y MELD de 20-30, split o donante vivo, coledocoyeyunostomía, altos requerimientos transfusionales, fracaso renal sin necesidad de terapia sustitutiva, reintervención precoz o colonización multifocal o infección por Candida, y trasplante de páncreas e intestino sin factores de riesgo para el tratamiento con equinocandina. Debe considerarse la profilaxis antifúngica con anfotericina B liposómica en el trasplante pulmonar (vía inhalada) y el trasplante hepático con los principales factores de riesgo. Debe considerarse la profilaxis antifúngica con voriconazol en el trasplante pulmonar y el trasplante cardíaco con hemodiálisis, reexploración quirúrgica postrasplante, colonización ambiental por Aspergillus o enfermedad por citomegalovirus.

ConclusionesEl manejo de la profilaxis antifúngica del paciente trasplantado de órgano sólido requiere la aplicación de los conocimientos y destrezas que se detallan en nuestras recomendaciones y en el algoritmo desarrollado. Estas recomendaciones basadas en la metodología Delphi pueden ayudar a identificar a los potenciales pacientes, estandarizar su tratamiento en conjunto y mejorar su pronóstico.

Solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients have a very high risk of invasive fungal infection (IFI), especially by Candida, Aspergillus, and, to a lesser degree, by Cryptococcus, mucorales and other filamentous fungi.17

In almost 50% of the IFI cases in SOT recipients, Candida is the most prevalent pathogen.17 Even though the incidence of invasive candidiasis (IC) varies depending on the transplanted organ – certainly high in liver, pancreas and intestinal transplants17 and very rare in the case of heart transplants21 –, the rate of global mortality in a period of 12 months associated to IC is 34%.20 Candidemia is the most common IC clinical presentation, and its incidence rate in SOT recipients is established at around 4%.13

On the other hand, the invasive aspergillosis (IA) rate in Europe varies from 0.2% to 3.5%, depending on the type of SOT recipients, being significantly more common in lung transplants.14 Despite the traditional consideration of IA as a complication associated to immediate post-transplantation, the risk continues high up to three months after the intervention.5

The type of SOT recipients conditions the selection of universal prophylaxis versus guided prophylaxis. Nevertheless, the existence of different inter-center protocols and the diverse epidemiology of fungal infections among different programs, makes it difficult to establish definitive recommendations on prophylaxis in SOT recipients.6,7 In this context, IFI in SOT recipients is an excellent target for the use of antifungal prophylaxis.28

The primary goal of this research is to analyze the current situation of antifungal prophylaxis in SOT recipients in hospitals throughout the country, and to obtain a set of therapeutic recommendations for different situations through the DELPHI methodology. For this purpose, a panel including specialists from six scientific societies was formed – Spanish Society of Mycology (AEM), as the promoter; the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC); the Spanish Society of Anesthesiology, Reanimation and Pain Therapeutics (SEDAR); the Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC); the Spanish Society of Chemotherapy (SEQ); the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacies (SEFH) – all with extensive experience in the treatment of critically-ill patients. They were requested to answer a questionnaire drafted by the seven coordinators responsible for the study, who had previously conducted a thorough review of the existing literature, as performed in the two previous editions of this project.26,27

After the group of coordinators elaborated the resulting recommendations, a second round of analysis was conducted in a face-to-face meeting in which the 60 specialists distributed throughout the whole country, who care for solid organ transplant recipients, validated the pre-selected recommendations and the algorithm derived from them through a voting procedure.

The panel was made up of 30 specialists from different geographic locations in the country from six scientific societies involved in the study. The criteria of inclusion were based on their experience in the research of invasive fungal infections (IFI), as well as their expertise in antifungal prophylaxis in SOT recipients.

The Delphi methodology used in this study aimed to optimize the consultation process of the 30 panel members. More specifically, thanks to the Delphi methodology, we were able to identify the groups’ opinions; not only those of one individual, but of each of the experts in different areas of information as suggested by the coordinators.

An agreement/disagreement consensus for each question was achieved when scoring equal to or higher than 70% (21 out of 30) in Top 4 (score of 7 or more points) of the total number of experts consulted. The coordinators posed a total of 12 questions (Annex 1) to be assessed by the experts by means of a metric scale.

The study methodology was based on the development of only one phase aimed to discover the level of consensus of all questions. To fulfill this goal, between May 19 and 26, 2014, the 30 specialists (Annex 2) participating in the study anonymously answered the online questionnaire of 12 questions. The coordinators responsible for the systematic research of the literature to elaborate the questions did not answer the questionnaire.

Thereafter, as mentioned above, recommendations were extracted and an algorithm elaborated and validated by the 73 experts in a face-to-face meeting held on September 25, 2014 (Annex 3).

Results1. Variables considered risk factors for the development of aspergillosis in liver transplant recipientsAnswers provided by the coordinators: retransplant, the event of more than one acute rejection requiring the use of steroids or monoclonal antibodies during the first month, post-transplant renal failure, pretransplant fulminant liver failure, dialysis, poor graft function (basically primary graft failure), surgical reintervention, prior renal failure, severe bacterial infection requiring antibiotic therapy for more than 10 days, bile leak and/or primary hepaticojejustonomy, presence of vascular graft complications, transfusion requirement >10 red blood cell units, surgery time >10h, assisted ventilation >7 days.

RationaleThe existence of different inter-center protocols and the diverse epidemiology of fungal infections among different programs, makes it difficult to establish definitive recommendations on prophylaxis in SOT recipients.6,7 Although infections by Candida are the most common fungal infections in liver transplants, due to the high morbidity and mortality rates caused by Aspergillus infection, coverage in high-risk patients is necessary.2,6–8,22,23 In fact, aspergillosis is a serious and very common complication in liver transplants, whereas re-transplants and dialysis are the main risk factors to acquire infections by Aspergillus in this population.3

The majority of the panel members (92.9%) agreed on considering retransplant as a risk factor for acquiring an Aspergillus infection in liver transplant recipients. In particular, on a scale of 0–10 in which 10 stands for the highest score, 26 out of 28 experts granted this 7 or more points, so a consensual agreement was established (Top 4 ≥70%). In addition, the experts also reached consensus when defining the following items as aspergillosis risk factors: presence of more than one acute rejection requiring the use of steroids or monoclonal antibodies during the first month (24 out of 28 answers with 7 or more points; Top 4: 85.7), post-transplant renal failure (23, 82.1%), pre-transplant fulminant liver failure (23, 82.1%), dialysis (23, 82.1%), surgical re-intervention (20; 71.4%), previous renal failure with creatinine values >2mg/dl (20; 71.4%), appearance of serious bacterial infection requiring antibiotic therapy for more than 10 days (20; 71.4%), bile leak, bilomas, and/or primary hepaticojejunostomy (20; 71.4%), and the presence of vascular graft complications (20; 71.4%).

In contrast, consensus was not reached (Top 4 <70%) when considering the transfusion requirement >10 red blood cell units as an aspergillosis risk factor (18 out of 28 answers with 7 or more points; Top 4: 64.3%), surgery time >10h and assisted ventilation for a period superior to 7 days (16; 57.1%).

2. Agreement on antifungals considered prophylactic treatment in high-risk liver transplant recipientsAnswers provided by the coordinators: itraconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole, liposomal amphotericin B, amphotericin B lipid complex, anidulafungin, caspofungin, micafungin.

RationaleA prophylaxis treatment against Candida in high-risk liver transplant recipients is recommended. The effectiveness and good tolerability of fluconazole (100–400mg/during 21–60 days), as well as liposomal amphotericin B (1mg/kg/during 5 days) has been proven in this field.2,6–8,22,23 The study by Fortún et al. proves the effectiveness and tolerability of caspofungin in antifungal prophylaxis in high-risk liver transplant recipients.4

Most specialists positively assessed the prophylactic administration of caspofungin, anidulafungin and liposomal amphotericin B in high-risk liver transplant recipients. Specifically, on a scale of 0–10 points in which 10 stands for the highest level of agreement, 25 out of 28 experts (89.3%) granted 7 or more points to the administration of caspofungin under these circumstances; in the case of anidulafungin and liposomal amphotericin B, the opinion was shared by 22 participants (78.6%). Thus, a high consensual agreement was reached regarding these three antifungals (Top 4 ≥70%).

In contrast, no consensus was achieved when considering the convenience of prescribing a prophylactic treatment with micafungin (19 out of 28 answers with 7 or more points; Top 4: 67.9%), amphotericin B lipid complex (10; 35.7%), voriconazole (8; 28.6%), itraconazole (8; 28.6%) or posaconazole (6; 21.4%) in this population.

3. Agreement on not administering any type of antifungal prophylaxis in liver transplant recipients in the absence of high-risk factorsRationaleThe incidence rate of aspergillosis in liver transplant recipients is just around 0.5%.10 In addition, although diverse studies have shown the incidence of infections caused by other filamentous fungi,19,24 there is not a clear recommendation about prophylaxis against them in SOT recipients. In this context, it should be taken into account that prevention against infections caused by filamentous fungi in SOT recipients is not a general practice, since the preferred measure is protecting transplant areas against massive inoculants, such as those produced during refurbishing works. Moreover, the use of HEPA filters is not necessary, as in the case of neutropenic patients.2,6–8,22,23

Only 18 out of 28 expert consultants (64.3%) did not consider necessary the administration of a prophylactic antifungal treatment in patients undergoing a liver transplant with no risk-factors, thus consensus was not established (Top 4 <70%).

4. Variables considered risk-factors for the development of aspergillosis in heart transplant recipientsAnswers provided by the coordinators: hemodialysis, surgical re-exploration after transplantation, environmental colonization by Aspergillus, cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections, acute rejection.

RationaleThe existence of different inter-center protocols and the diverse epidemiology of fungal infections among different programs, makes it difficult to establish definitive recommendations on prophylaxis in SOT recipients.2,6–8,22,23 Re-intervention, CMV infections, post-transplant hemodialysis and environmental colonization by Aspergillus are aspergillosis risk-factors in patients undergoing a heart transplant.15

The members of the board agreed on considering each and every one of the variables proposed by the coordinators as Aspergillus infection risk-factors in patients undergoing a heart transplant. Specifically, on a scale of 0–10, in which 10 stands for the highest level of agreement, 25 out of 28 experts (89.3%) granted 7 or more points to hemodialysis as a risk-factor; an assessment shared by 24 experts (85.7%) regarding re-exploration after transplantation and by 23 specialists (82.1%) regarding environmental colonization by Aspergillus spp., CMV infection and acute rejection, were collected. Therefore, a high level of consensus was achieved regarding the proposed variables (Top 4 ≥70%).

5. Agreement on the use of antifungals as a prophylactic treatment in heart transplant recipientsAnswers provided by the coordinators: itraconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole, liposomal amphotericin B, amphotericin B lipid complex, anidulafungin, caspofungin, micafungin

RationaleThe medical guidelines of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) recommend the administration of voriconazole or echinocandins in high-risk heart transplant recipients.6,7 Specifically, on a scale of 0–10 points, in which 10 stands for the highest level of agreement, 24 out of 28 experts (85.7%) granted 7 or more points to the administration of caspofungin in this situation; an opinion shared by 22 participants (78.6%) in the case of anidulafungin and micafungin, and by 20 experts (71.4%) in the case of voriconazole, were registered. There was, therefore, a high consensual agreement on the use of the four antifungals mentioned above (Top 4 ≥70%).

In contrast, consensus was not reached when considering the convenience of administering a prophylactic treatment with itraconazole (15 out of 28 answers with 7 or more points; Top 4: 53.6%), posaconazole (15; 53.6%) liposomal amphotericin B (14; 50%), and amphotericin B lipid complex (9; 32.17%) in this population.

6. Agreement on not administering any type of antifungal prophylactic treatment in heart transplant recipients in the absence of risk-factorsRationaleAntifungal prophylaxis is usually administered only in high-risk heart transplant recipients.16 Moreover, even though there are several studies which prove the incidence of infectious diseases caused by other filamentous fungi,19,24 there is not a clear recommendation on prophylaxis against them in SOT recipients. In this context, it should be taken into account that prevention against infections caused by filamentous fungi in SOT recipients is not a general practice, since the preferred measure is protecting transplant areas against massive inoculants, such as those produced during refurbishing works. Moreover, the use of HEPA filters is not necessary, as in the case of neutropenic patients.2,6–8,22,23

Most of the expert consultants (85.7%) agreed on the fact that antifungal prophylaxis is not necessary in patients undergoing a heart transplant in the absence of risk factors. Specifically, on a scale of 0–10 in which 10 stands for the highest rate of agreement, 24 out of 28 experts (85.7%) granted 7 or more points, so a consensual agreement was established (Top 4 ≥70%).

7. Variables considered risk factors for the development of aspergillosis in pancreas or intestinal transplant recipientsAnswers provided by the coordinators: over-immunosuppression, acute graft rejection, hemodialysis, initial graft dysfunction, anastomotic problems, need for laparotomy after transplantation, cytomegalovirus infection, bacterial infection.

RationaleThe existence of different inter-center protocols and the diverse epidemiology of fungal infections among different programs, makes it difficult to establish definitive recommendations on antifungal prophylaxis in SOT recipients.6,7 Although infections by Candida are the most common fungal infections in pancreas9 transplants and intestinal1 transplants, the high morbidity and mortality rates of infections caused by Aspergillus in high-risk patients makes its coverage necessary.2,6–8,22,23

Most members of the panel (92.9%) agreed on considering over-immunosupression and acute graft rejection as aspergillosis risk factors in patients undergoing pancreas or intestinal transplants.

Specifically, on a scale of 0–10 points in which 10 stands for the highest level of agreement, 26 out of 28 experts granted 7 or more points to both variables, thus, a consensual agreement was reached (Top 4 ≥70%). Moreover, consensus was also reached when considering hemodialysis (25 out of 28 answers with 7 or more points; Top 4: 89.3%), initial graft dysfunction (25; 89.3%), anastomotic problems (23; 82.1%), need for laparotomy after transplantation (23; 82.1%) and CMV infection as Aspergillus infection risk factors.

In contrast, consensus was not reached (Top 4 <70%) when considering bacterial infections (18 out of 28 answers with 7 or more points; Top 4: 64.3%) as aspergillosis risk factor in this population.

8. Agreement on the use of antifungals as a prophylactic treatment in high-risk pancreas or intestinal transplant recipientsAnswers provided by the coordinators: itraconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole, liposomal amphotericin B, amphotericin B lipid complex, anidulafungin, caspofungin, micafungin.

RationaleIt is recommended to prescribe a prophylactic treatment against Candida in pancreas and intestinal transplant recipients. The administration of fluconazole (100–400mg/d during 21–60 days), as well as liposomal amphotericin B (1mg/kg/d during 5 days) has proven effectiveness and a good tolerability in this field.2,6–8,18,22,23

The majority of specialists positively valued the administration of echinocandins – anidulafungin, caspofungin, micafungin – as a prophylactic treatment in high-risk pancreas or intestinal transplant recipients. Specifically, on a scale of 0–10 points in which 10 stands for the highest level of agreement, 24 out of 28 experts (85.7%) granted 7 or more points to the administration of anidulafungin in this situation; an opinion shared by 22 participants (78.6%) in the case of the administration of caspofungin and micafungin was also registered. Thus, a high consensual agreement was reached regarding these three echinocandins (Top 4 ≥70%).

In contrast, no consensus was reached when considering the convenience of prescribing a prophylactic treatment with liposomal amphotericin B (18 out of 28 answers with 7 or more points; Top 4: 64.3%), amphotericin B lipid complex (10; 35.7%), or an extended azole spectrum voriconazole (14; 50%), posaconazole (9; 32.1%), itraconazole (8; 28.6%) in this population.

9. Agreement on not administering any type of antifungal prophylaxis in pancreas or intestinal transplant recipients in the absence of high-risk factorsRationaleDespite of the lack of studies in scientific literature designed to evaluate the role of antifungal prophylaxis in intestinal transplant recipients, its administration should be recommended due to the high risk of infection by Candida in this population. Likewise, it is recommended to prescribe a prophylactic treatment in pancreas transplant recipients.2,6–8,18,22,23

Only 11 out of 28 experts (39.3%) agreed on pointing out that antifungal prophylaxis is not necessary for patients undergoing a pancreas or intestinal transplant in the absence of risk factors, thus consensus was not established (Top 4 <70%) in this case.

10. Agreement on the use of antifungals as a prophylactic treatment in lung transplant recipientsAnswers provided by the coordinators: itraconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole, inhalant form of liposomal amphotericin B, amphotericin B lipid complex, anidulafungin, caspofungin, micafungin.

RationaleLung transplant recipients benefit from the administration of amphotericin B nebulizer (6mg/8h 4 months, and afterwards every 24h longlife) or voriconazole for no less than 12 months as a prophylactic treatment against Aspergillus.6,7,11,25

Most members of the panel agreed on the convenience of administering inhaled amphotericin B and voriconazole as a prophylactic treatment in lung transplant recipients.

Specifically, on a scale of 0–10 in which 10 stands for the highest rate of agreement, 24 out of 28 experts (85.7%) granted 7 or more points to the administration of inhaled amphotericin B and voriconazole in this situation, thus consensus was established regarding both therapeutic alternatives (Top 4 ≥70%).

In contrast, there was no consensus when considering a prophylactic treatment with amphotericin B lipid complex (14 out of 28 answers with 7 or more points; Top 4: 50%), posaconazole (13; 46.4%), itraconazole (9; 32.1%) or an echinocandin – caspofungin (12; 42.9%), anidulafungin (11; 39.3%), micafungin (11; 39.3%) – in this population.

11. Agreement on the duration of the prophylactic treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in kidney transplant recipientsRationaleKidney transplant recipients only need prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii.6,7 The most extended prophylactic treatment to prevent infections by P. jirovecii is the administration of cotrimoxazole, a drug which also has activity against Listeria, Toxoplasma, Nocardia and Legionella, among others. Cotrimoxazole may be administered in different regimens (trimethoprim 160mg+sulfamethoxazole 800mg/12h Saturdays and Sundays, trimethoprim 160mg+sulfamethoxazole 800mg/day, 3 days a week, trimethoprim 160mg+sulfamethoxazole 800mg/day, etc.).

A consensus was not reached by experts (Top 4 <70%) on the convenience of the three periods of time proposed by the coordinators for the maintenance of prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in kidney transplant recipients: 3 months (18 out of 28 answers with 7 points or more; Top 4: 64.3%), 6 months (17; 60.7%), and 1 year (3; 10.7%).

12. Agreement on the duration of the prophylactic treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the rest of transplant recipientsAnswers provided by the coordinators: 3 months, 6 months, 1 year.

RationaleProphylaxis must be initiated after surgery and cover at least the maximum risk period (6–12 months). In this context, it should be remembered that prophylaxis cannot eradicate P. jirovecii, so it will only be effective if continuously administered.6,7,12

Most members of the panel (71.4%) agreed on pointing out the need to maintain prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for a year in patients who have undergone a solid organ transplant – not renal transplants. Specifically, on a scale of 0–10 in which 10 stands for the highest rate of agreement, 20 out of 28 experts granted 7 or more points, so a consensual agreement was established (Top 4 ≥70%) for a 1 year duration treatment (20 answers in Top 4; 71.4%). As for the rest of the periods proposed by the coordinators, only 10 specialists (35.7%) granted 7 or more points to a 6 month period of prophylaxis and 7 experts granted points to a 3 month period of prophylaxis (25%).

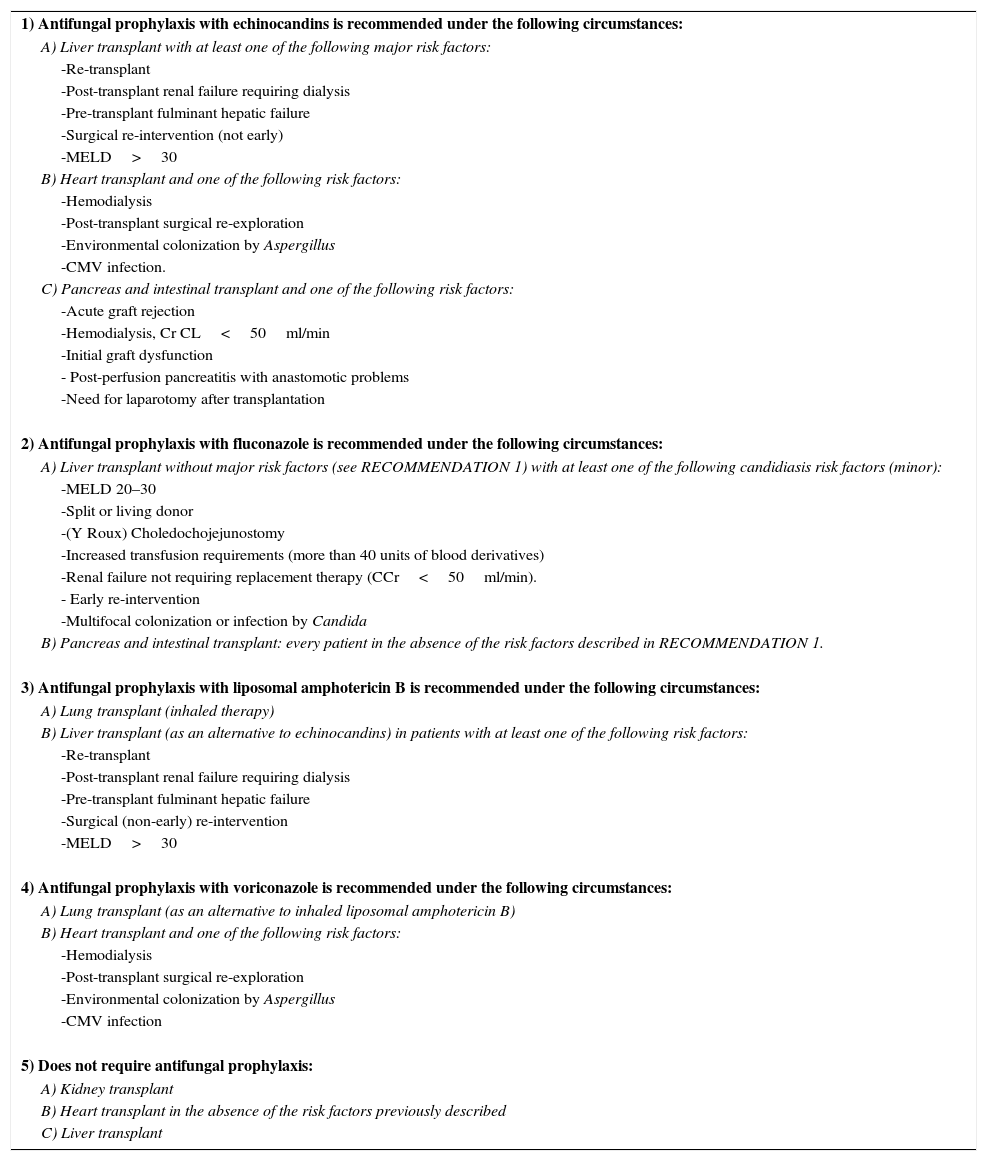

Recommendations and algorithmOnce the results achieved in the Delphi methodology regarding antifungal prophylaxis in solid organ transplant recipients were collected, five recommendations were elaborated and the conclusions are exhibited in Table 1. They are based on the questions which reached a consensus equal or higher than 70%. These recommendations and the algorithm deriving from them (Fig. 1) were validated thereafter during a face-to-face meeting with the hospital experts.

Recommendations in SOT patients.

| 1) Antifungal prophylaxis with echinocandins is recommended under the following circumstances: |

| A) Liver transplant with at least one of the following major risk factors: |

| -Re-transplant |

| -Post-transplant renal failure requiring dialysis |

| -Pre-transplant fulminant hepatic failure |

| -Surgical re-intervention (not early) |

| -MELD>30 |

| B) Heart transplant and one of the following risk factors: |

| -Hemodialysis |

| -Post-transplant surgical re-exploration |

| -Environmental colonization by Aspergillus |

| -CMV infection. |

| C) Pancreas and intestinal transplant and one of the following risk factors: |

| -Acute graft rejection |

| -Hemodialysis, Cr CL<50ml/min |

| -Initial graft dysfunction |

| - Post-perfusion pancreatitis with anastomotic problems |

| -Need for laparotomy after transplantation |

| 2) Antifungal prophylaxis with fluconazole is recommended under the following circumstances: |

| A) Liver transplant without major risk factors (see RECOMMENDATION 1) with at least one of the following candidiasis risk factors (minor): |

| -MELD 20–30 |

| -Split or living donor |

| -(Y Roux) Choledochojejunostomy |

| -Increased transfusion requirements (more than 40 units of blood derivatives) |

| -Renal failure not requiring replacement therapy (CCr<50ml/min). |

| - Early re-intervention |

| -Multifocal colonization or infection by Candida |

| B) Pancreas and intestinal transplant: every patient in the absence of the risk factors described in RECOMMENDATION 1. |

| 3) Antifungal prophylaxis with liposomal amphotericin B is recommended under the following circumstances: |

| A) Lung transplant (inhaled therapy) |

| B) Liver transplant (as an alternative to echinocandins) in patients with at least one of the following risk factors: |

| -Re-transplant |

| -Post-transplant renal failure requiring dialysis |

| -Pre-transplant fulminant hepatic failure |

| -Surgical (non-early) re-intervention |

| -MELD>30 |

| 4) Antifungal prophylaxis with voriconazole is recommended under the following circumstances: |

| A) Lung transplant (as an alternative to inhaled liposomal amphotericin B) |

| B) Heart transplant and one of the following risk factors: |

| -Hemodialysis |

| -Post-transplant surgical re-exploration |

| -Environmental colonization by Aspergillus |

| -CMV infection |

| 5) Does not require antifungal prophylaxis: |

| A) Kidney transplant |

| B) Heart transplant in the absence of the risk factors previously described |

| C) Liver transplant |

This consensus has been sponsored by MSD Laboratories, Spain.

We thank Carmen Romero and Ainhoa Torres (Entheos Editorial Group) for their excellent work and dedication to this project.

Rafael Zaragoza Crespo

Intensive Care Department, Dr. Peset University Hospital. Valencia, Spain

Ricard Ferrer Roca

Intensive Care Department, Vall d¿Hebron University Hospital. Barcelona, Spain

Alejandro Hugo Rodríguez

Intensive Care Department, Joan XXIII University Hospital. Tarragona, Spain

Emilio Maseda Garrido

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, La Paz University Hospital. Madrid, Spain

Pedro Llinares Mondéjar

Infectious Diseases Department, A Coruña University Complex. A Coruña, Spain

Santiago Grau Cerrato

Pharmacy Department, Hospital del Mar. Barcelona, Spain

José María Aguado García

Infectious Diseases Department, 12 de Octubre University Hospital. Madrid, Spain

Gerardo Aguilar Aguilar

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Valencia Clinical University Hospital. Valencia, Spain

Benito Almirante Gragera

Infectious Diseases Department, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital. Barcelona, Spain

Francisco Álvarez Lerma

Intensive Care Department, Hospital del Mar. Barcelona, Spain

César Aragón González

Intensive Care Department, Carlos Haya University Hospital. Málaga, Spain

María Izaskun Azcárate Egaña

Intensive Care Department, Donostia University Hospital. Donostia, Spain

Marcio Borges Sa

Sepsis Unit Coordinator, Son Llàtzer Hospital. Palma de Mallorca, Spain

Mercedes Bouzada Rodríguez

Anaesthesia, Resuscitation and Pain Therapy Department, University Hospital Clinic of Santiago. Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Juan Carlos del Pozo Laderas

Intensive Care Department, Reina Sofía University Hospital. Córdoba, Spain

Carmen Fariñas Álvarez

Intensive Care Department, Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital. Santander, Spain

Jesús Fortún Abete

Infectious Diseases Department, Ramón y Cajal University Hospital. Madrid, Spain

Beatriz Galván Guijo

Intensive Care Department, La Paz University Hospital. Madrid, Spain

José Garnacho Montero

Intensive Care Department, Virgen del Rocío University Hospital. Sevilla, Spain

José Ignacio Gómez Herreras

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Valladolid Clinical University Hospital. Valladolid, Spain

Rafael Huarte Lacunza

Pharmacy Department, Miguel Servet University Hospital. Zaragoza, Spain

Cristóbal León Gil

Intensive Care Department, Valme University Hospital. Sevilla, Spain

Rafael León López

Intensive Care Department, Reina Sofía University Hospital. Córdoba, Spain

Patricia Muñoz García

Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Department, Gregorio Marañón University Hospital. Madrid, Spain

Jordi Nicolás Picó

Pharmacy Department, Son Llàtzer Hospital. Palma de Mallorca, Spain

Pedro Olaechea Astigarraga

Intensive Care Department, Galdakao Usansolo Hospital. Vizcaya, Spain

Javier Pemán García

Microbiology Unit, La Fe University and Polythecnic Hospital. Valencia, Spain

María Luisa Pérez del Molino Bernal

Microbiology and Parasitology Unit, Santiago de Compostela University Hospital Complex. Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Leonor Periañez Párraga

Pharmacy Department, Son Espases University Hospital. Palma de Mallorca, Spain

Guillermo Quindós Andrés

Microbiology Unit, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Basque Country University. Vizcaya, Spain

Jesús Rico Feijoo

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Río Hortega University Hospital. Valladolid, Spain

María Rodríguez Mayo

Microbiology Unit, A Coruña University Hospital Complex. A Coruña, Spain

Eva Romá Sánchez

Pharmacy Department, La Fe University and Polythecnic Hospital. Valencia, Spain

Isabel Ruiz Camps

Infectious Diseases Department, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital. Barcelona, Spain

Miguel Salavert Lleti

Infectious Diseases Department, La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital. Valencia, Spain

Juan Carlos Valía Vera

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, General University Hospital Consortium. Valencia, Spain

César Aldecoa Álvarez-Santullano

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Río Hortega University Hospital. Valladolid, Spain

Rosa Ana Álvarez Fernández

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Asturias Central University Hospital. Asturias, Spain

Rocío Armero Ibáñez

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Doctor Peset University Hospital. Valencia, Spain

Fernando Armestar Rodríguez

Intensive Care Department, Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital. Badalona, Barcelona, Spain

Miguel Ángel Arribas Santamaría

Intensive Care Department, Arnau de Vilanova Hospital. Valencia, Spain

José Ignacio Ayestarán Rota

Intensive Care Department, Son Espases University Hospital. Palma de Mallorca, Spain

María Ángeles Ballesteros Sanz

Intensive Care Department, Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital. Santander, Spain

María José Bartolomé Pacheco

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital. Santander, Spain

Unai Bengoetxea Uriarte

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Basurto Hospital. Bilbao, Vizcaya, Spain

Eva Benveniste Pérez

Intensive Care Department, Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital. Badalona, Barcelona, Spain

José Blanquer Olivas

Intensive Care Department, Valencia Clinical University Hospital. Valencia, Spain

Felipe Bobillo del Amo

Intensive Care Department, San Carlos Clinical University Hospital. Madrid, Spain

Ángel Caballero Sáez

Intensive Care Department, San Millán Hospital Complex- San Pedro Hospital. Logroño, La Rioja, Spain

Andrés Carrillo Alcaraz

Intensive Care Department, Morales Meseguer University General Hospital. Murcia, Spain

José Castaño Pérez

Intensive Care Department, Virgen de las Nieves University Hospital. Granada, Spain

Pedro Castro Rebollo

Intensive Care Department, Clínic i Provincial of Barcelona Hospital. Barcelona, Spain

Milagros Cid Manzano

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Complex of Ourense University Hospital. Ourense, Spain

Belén Civantos Martín

Intensive Care Department, La Paz University Hospital. Madrid, Spain

María Victoria de la Torre Prados

Intensive Care Department, Virgen de la Victoria University Hospital. Málaga, Spain

David Domínguez García

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria University Hospital. Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain

Juan Ramón Fernández Villanueva

Intensive Care Department, Complex of Santiago Compostela University Hospital. A Coruña, Spain

Rafael García Hernández

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Puerta del Mar University Hospital. Cádiz, Spain

Rafael Franco Llorente

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Virgen de las Nieves University Hospital. Granada, Spain

Luis Gajate Martín

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Ramón y Cajal University Hospital. Madrid, Spain

Emilio García Prieto

Intensive Care Department, Asturias Central University Hospital. Oviedo, Asturias, Spain

Pau Garro Martínez

Intensive Care Department, Granollers General Hospital. Barcelona, Spain

Carolina Giménez-Esparza Vic

Intensive Care Department, Vega Baja Hospital. Orihuela, Alicante, Spain

Ricardo Gimeno Costa

Intensive Care Department, La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital. Valencia, Spain

Francisco Javier González de Molina Ortiz

Intensive Care Department, Mutua de Terrassa University Hospital. Barcelona, Spain

Marta Gurpegui Puente

Intensive Care Department, Miguel Servet University Hospital. Zaragoza, Spain

María José Gutiérrez Fernández

Intensive Care Department, San Agustín Hospital. Avilés, Asturias, Spain

Joaquín Lobo Palanco

Intensive Care Department, Navarra Hospital Complex. Pamplona, Navarra, Spain

Mauro Loinaz Bordonabe

Intensive Care Department, Navarra Hospital Complex. Pamplona, Navarra, Spain

Esther María López Ramos

Intensive Care Department, Príncipe de Asturias University Hospital. Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Spain

María Pilar Luque Gómez

Intensive Care Department, Lozano Blesa Clinic University Hospital. Zaragoza, Spain

Juan Francisco Machado Casas

Intensive Care Department, Jaén Hospital Complex. Jaén, Spain

José Miguel Marcos Vidal

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Virgen Blanca Hopital Complex. León, Spain

Fernando Maroto Monserrat

Intensive Care Department, San Juan de Dios del Aljarafe Hospital. Bormujos, Sevilla, Spain

Juan Carlos Martínez Cejudo

Intensive Care Department, Infanta Elena University Hospital. Huelva, Spain

María del Carmen Martínez Ramagge

Intensive Care Department, La Línea Hospital (AGSCampo of Gibraltar). La Línea de la Concepción, Cádiz, Spain

Ignacio Moreno Puigdollers

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital. Valencia, Spain

Lorena Mouríz Fernández

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Lucus Augusti University Hospital. Lugo, Spain

Luis Alberto López Olaondo

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Navarra University Clinic. Pamplona, Navarra, Spain

Sergio Ossa Echeverri

Intensive Care Department, Burgos University Hospital. Burgos, Spain

Juan Carlos Pardo Talavera

Intensive Care Department, Reina Sofía General University Hospital. Murcia, Spain

Inés María Parejo Cabezas

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, San Pedro de Alcántara Hospital. Cáceres, Spain

Jorge Pereira Tamayo

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Álvaro Cunqueiro University Hospital. Vigo, Pontevedra, Spain

Miguel Ángel Pereira Loureiro

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Álvaro Cunqueiro University Hospital. Vigo, Pontevedra, Spain

Ana Pérez Carbonell

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Elche General University Hospital. Alicante, Spain

Marcos Pérez Carrasco

Intensive Care Department, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital. Barcelona, Spain

Demetrio Pérez Civantos

Intensive Care Department, Infanta Cristina University Hospital. Badajoz, Spain

María José Pérez-Pedrero Sánchez-Belmonte

Intensive Care Department, Virgen de la Salud Hospital. Toledo, Spain

David Pestaña Lagunas

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Ramón y Cajal University Hospital. Madrid, Spain

Pedro Picatto Hernández

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Asturias Central University Hospital. Oviedo, Asturias, Spain

Rosa Poyo-Guerrero Lahoz

Intensive Care Department, Son Llàtzer Hospital. Palma de Mallorca, Spain

Luis Quecedo Gutiérrez

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, La Princesa University Hospital. Madrid, Spain

Roberto Reig Valero

Intensive Care Department, Castellón General Hospital. Castellón, Spain

Manuel Rodríguez Carvajal

Intensive Care Department, Juan Ramón Jiménez Hospital. Huelva, Spain

Enrique Samsó Sabé

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Hospital del Mar. Barcelona, Spain

Catalina Sánchez Ramírez

Intensive Care Department, Doctor Negrín of Gran Canaria University Hospital. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain

Margarita Sánchez Castilla

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda University Hospital. Madrid, Spain

Susana Sancho Chinesta

Intensive Care Department, Doctor Peset University Hospital. Valencia, Spain

Juan Carlos Sotillo Díaz

Intensive Care Department, Gregorio Marañón General University Hospital. Madrid, Spain

José Manuel Soto Blanco

Intensive Care Department, San Cecilio University Hospital. Granada, Spain

Luis Suárez Gonzalo

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, La Paz University Hospital. Madrid, Spain

Teresa Tabuyo Bello

Intensive Care Department, A Coruña University Hospital. A Coruña, Spain

Eduardo Tamayo Gómez

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Valladolid Clinic University Hospital. Valladolid, Spain

Luis Mariano Tamayo Lomas

Intensive Care Department, Río Hortega University Hospital. Valladolid, Spain

Gonzalo Tamayo Medel

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Cruces University Hospital. Bilbao, Vizcaya, Spain

Vicente Torres Pedrós

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Son Espases University Hospital. Palma de Mallorca, Spain

Montserrat Vallverdú Vidal

Intensive Care Department, Arnau de Vilanova University Hospital. Lleida, Spain

Marina Varela Durán

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Pontevedra University Hospital Complex. Pontevedra, Spain

Paula Vera Artazcoz

Intensive Care Department, Santa Creu i Sant Pau Hospital. Barcelona, Spain

María Elena Vilas Otero

Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical Critical Care, Álvaro Cunqueiro University Hospital. Pontevedra, Spain