Post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) is common among patients undergoing surgical procedures with spinal anesthesia. Conservative therapy might be associated with poor outcomes and delayed recovery. The aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of acupuncture on post-dural puncture headache in comparison to conservative treatment.

MethodIn this single-blind randomized clinical trial 60 PDPH patients were divided into three groups. Group A received conservative pharmacological treatment, group B received acupuncture and group C received acupuncture sham. Outcomes were measured as pain intensity (visual analog scale VAS) and recovery time (time that pain falls from 4–7 to 0–3 on visual analog scale).

ResultsAll three groups had no significant difference in terms of gender, age, and baseline pain (immediately after the surgery). Pain intensity decreased significantly in acupuncture group comparing to other groups. Furthermore, acupuncture reduced pain faster than other treatments. The overall general condition of the patients in group A and B was not significantly different, however significantly improved compared to group C.

ConclusionAcupuncture therapy can be an effective method to manage PDPH in a shorter time and can reduce the need for epidural blood patch and pharmacological analgesia. However, further randomized trails are required to validate these findings.

La cefalea pospunción dural (PHPD) es común entre los pacientes sometidos a un procedimiento quirúrgico con raquianestesia. La terapia conservadora puede estar asociada a malos resultados y recuperación tardía. El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar el efecto de la acupuntura sobre la PHPD en comparación con el tratamiento conservador.

MétodoEn este ensayo clínico aleatorio simple ciego se dividió a los 60 pacientes con PHPD en 3 grupos. El grupo A recibió tratamiento farmacológico conservador, el grupo B recibió acupuntura, y el grupo C recibió acupuntura simulada. Los resultados se midieron como intensidad del dolor (escala analógica visual EVA) y tiempo de recuperación (tiempo en que el dolor cae de 4-7 a 0-3 en la escala analógica visual).

ResultadosLos 3 grupos no tuvieron diferencias significativas en términos de sexo, edad y dolor inicial (inmediatamente después de la cirugía). La intensidad del dolor disminuyó significativamente en el grupo de acupuntura en comparación con los demás grupos. Además, la acupuntura redujo el dolor más rápidamente que otros tratamientos. El estado general de los pacientes de los grupos A y B no fue significativamente diferente, pero mejoró significativamente en comparación con el grupo C.

ConclusiónLa terapia de acupuntura puede ser un método efectivo para manejar PHPD en un tiempo más corto, y puede reducir la necesidad de parches sanguíneos epidurales y analgesia farmacológica. Sin embargo, se requieren más pruebas aleatorias para validar estos hallazgos.

One of the complications of spinal anesthesia is a headache called Spinal headache or Post Dural puncture headache (PDPH). Despite preventive measures, PDPH is still seen in 0.16%–1.3% patients in experienced hands whereas in 86% of the patients are presented with PDPH due to the usage of large needle used for epidural.1 It can cause discomfort and brain injuries in severe cases.2 The leakage of cerebrospinal fluid into the dura as a result of puncture hole is a known cause of PDPH.3

A number of therapeutic strategies are practiced to treat PHPD effectively.4 The current PDHP treatment is based on conservative therapies and if the headache persists for up to 24h, normal saline, caffeine and epidural blood patches are used. Prolonged hospitalization also add to economic burden to the health care sector.5

Several researches have indicated the analgesic use of acupuncture and it is associated with the reduced need of pharmacological agents.6,7 Conservative treatments are associated with a number of side effects whereas acupuncture has low-to-no side effects.8 It is also effective against different types of headaches.9–11 Acupuncture against PHPD has been supported by some case reports.12

This is a first randomized control trial designed to evaluate the effects of acupuncture in comparison to conservative treatment against moderate PHPD among patients who underwent surgical procedure using spinal anesthesia.

MethodsThe randomized clinical trial was conducted on all the patients referred to Imam Reza Hospital for surgery under spinal anesthesia. Patients who underwent spinal anesthesia and experienced headache were evaluated using VAS (visual analog scale). The patients were randomly (electronically) divided into three groups of 20 each: (A) Common supportive treatment, (B) Acupuncture treatment, (C) Sham acupuncture treatment.

Spinal anesthesia was administered with 24-gauge Sprotte needle using hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% at L4–L5 level in a single puncture by an experienced anesthesiologist and patients with PDPH from 24h to 7 days were examined using VAS scale. The patients were sufficiently hydrated using intravenous saline before anesthesia to reduce the incidence of hypotension. The headache was seen to worsen with 15min when the patients moved from supine with upright position and got better when patients lie down. The headache was typically associated with postural changes. The international criteria for classification of headache disorders was used to identify PDPH.13 Patients with moderate pain, i.e. score from 3 to 7 on the visual analog scale were included in the study. Patients were under ASA I or II class. Written consent was obtained from all the patients for the participation in the study.

Patients with chronic headache, those who had taken painkillers 24h earlier and those with VAS scores of 0–3 or 7–10, categorized as mild and severe headache, respectively, were excluded from the study.

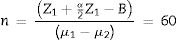

The sample size of the study was calculated using the following function:

Because the study groups were randomly selected and all the patients were referred to the same hospital, having similar socioeconomic status and confounding factors of exclusion criteria, we expected the groups to be the same. If they were not identical in terms of confounding factors, it was decided to control the effect of confounding factors by stratification. Each patient had a two-digit code, the digit on the left of the patient group code (1–3) and the digit to the right was the patient number in that group. The researcher who evaluated pain in patients was not aware of the type of intervention.

Conservative treatment: Patients in this group was under bed rest and were advised to drink at least 2l of fluid per day, with the use of analgesics (codydramol composed of dihydrocodeine tartrate and paracetamol, 2 tablets every 6h, diclofenac 50mg every 8h and dexamethasone ampoule was provided).

Acupuncture group received one course of treatment after reporting the pain. Acupuncture was performed in British form at trigger points, target points and fixed points of acupuncture according to acupuncture protocols. Acupuncture points were selected as follows: (1) for headache: Gallbladder 14, 20 and 21; (2) for neck pain: 12 small intestine plus trigger points; (3) for colon: 4 relaxation points as follows: Gallbladder 14 1 inch above the eyebrow line. Gallbladder 20: below the occiput. Gallbladder 21: connecting half CV line acromion. Small intestine 12: upper middle scapula colon 4: (length of fingertip sixty) from the edge of the webbed space (fingertips) between the index finger. Needles of a size of 0.25 and a length of 13–33mm were used. 1–2mm of the needles were inserted and were maneuvered for a few seconds with repetitive twisting according to the principles of the technique. The acupuncture needles were then left there for about 10min. Immediately before removal, each needle was manipulated up again for a few seconds. Acupuncture treatment was performed twice in 48h. In the sham acupuncture group, similar needles were used in the same places but without effect (sinking).

Data collectionImmediately after treatment, at intervals of 30min, 3h, 6h later, 12h later, 24h, 48h and 7 days from the start of treatment in each group, the pain was assessed using VAS. For 7 days, we assessed the patient's general condition, which was based on the patient's own rating of his health status; improve, worsen or no change.

Statistical analysisThe data was computerized and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v22. The difference in variables was measured by descriptive and analytical statistics using Fisher's exact test and one-way ANOVA. If the groups were not the same in terms of confounding factors, stratification and Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel method was used. The mean severity of headache between the three treatment groups was measured by Kruskall–Wallis test. The reduction in the headache (average pain reduction) was analyzed by longitudinal data analysis using linear mixed model (linear mixed models). The recovery time was estimated by survival analysis using Kaplan–Meier test.

Ethical parametersPatients who did not show improvement in headache were treated with epidural blood patch, if the pain level did not decrease within 30min after treatment. At any stage of the study where patient did not wish to continue the collaboration, he/she was excluded from the study. The study was approved by the board of ethical committee of Imam Reza Hospital.

ResultsDemographic dataA total of 60 patients entered our study, who were equally divided in three groups, as discussed in previous section. A patient in group B (acupuncture group) suffered from severe headache, VAS=8 and was treated with blood patch, however, was replaced with another patient. All the patients included in the study were men, 100%.

The mean age of the all patients included in 31.1±10.0 years, ranging from 19 to 55 years. In group A, the mean age of the patients was 33.7±11.2 years, in group B was 28.1±8.0 years and in group C was 31.7±10.2 years. The age difference between the three groups was not statistically significant (p=0.2).

Type of surgeryThe surgeries performed were divided into two categories: orthopedic (26 cases and 43.3% of the total) and urology (34 cases and 56.7% of the total). The details of the type of surgeries performed are provided in Fig. 2. The difference in type surgeries performed in the three groups was not statistically significant (p=0.8).

Duration of the surgeryThe duration of surgery in all groups varied from 30mins to 95min (188.5±13.72min). The duration of the surgery in all three groups is provided in (Fig. 1). The difference in surgery duration was statistically significant among the groups (p=0.02).

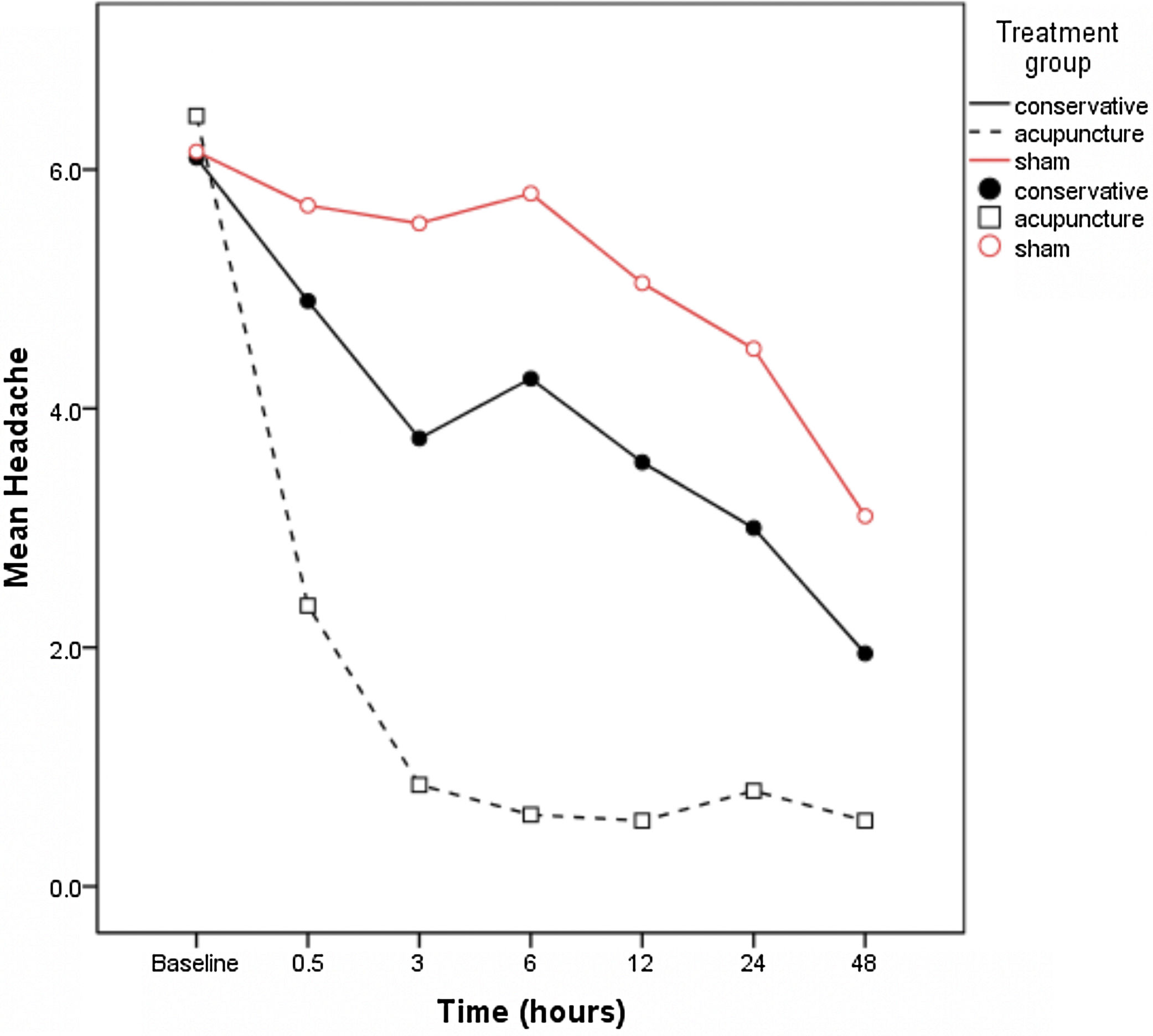

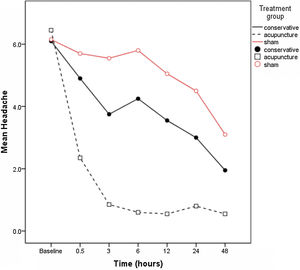

PainHeadache at various postoperative intervals; 30min, 3h, 6h, 24h, 48h 7 days after each intervention all the groups is summarized in Table 1. The baseline headache (immediately) after the surgery was not significantly different among the three groups, p=0.326. However, following the intervention, at all the intervals the pain scores were significantly different among the three groups, p<0.05.

Mean and standard deviation of headache 30min, 3h, 6h, 24h, 48h 7 days after each intervention in each treatment group.

| Time (h) | Total | Group | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Acupuncture | Sham | |||

| Baseline | 6.2±0.8 | 6.1±0.9 | 6.5±0.8 | 6.2±0.8 | 0.326 |

| 6 (5–7) | 6 (5–7) | 7 (5–7) | 6 (5–7) | ||

| 0.5 | 4.3±2.1 | 4.9±1.8 | 2.4±1.9 | 5.7±1 | <0.001 |

| 5 (0–7) | 5 (2–7) | 2.5 (0–7) | 6 (3–7) | ||

| 3 | 3.4±2.3 | 3.8±1.3 | 0.9±1.2 | 5.6±1.2 | <0.001 |

| 3 (0–7) | 3 (2–7) | 0.5 (0–4) | 5 (3–7) | ||

| 6 | 3.6±2.5 | 4.3±1.5 | 0.6±1.1 | 5.8±1.1 | <0.001 |

| 3.5 (0–7) | 3.5 (3–7) | 0 (0–4) | 6 (3–7) | ||

| 12 | 3.1±2.3 | 3.6±1.6 | 0.6±1.1 | 5.1±1.4 | <0.001 |

| 3 (0–7) | 3 (0–7) | 0 (0–4) | 5 (1–7) | ||

| 24 | 2.8±2.1 | 3±1.7 | 0.8±1.2 | 4.5±1.3 | <0.001 |

| 3 (0–7) | 3 (0–6) | 0 (0–4) | 5 (1–7) | ||

| 48 | 1.9±1.9 | 2±1.8 | 0.6±1.2 | 3.1±1.7 | <0.001 |

| 2 (0–7) | 2.5 (0–6) | 0 (0–4) | 3 (0–7) | ||

| 7 days | 0.3±0.7 | 0.3±0.8 | 0±0 | 0.5±0.8 | 0.016 |

| 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–3) | ||

Results are presented as mean±SD, median (range).

Post hoc test was used to evaluate the severity of headache in the treatment groups (A and B). The results showed that at any time other than zero, the severity of headache in the acupuncture group was significantly lower than the conservative treatment group and the sham group (p<0.05) and also at all the time the severity of headache in the conservative group was significantly lower than the sham group (p<0.05).

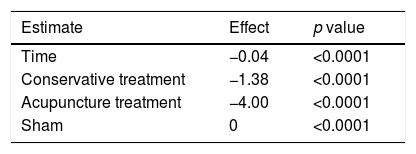

According to the longitudinal data analysis, the results showed that the average pain reduction in the acupuncture group was significantly more than other groups, p<0.001. This means that if we consider sham as the base, after 1h, the average pain in the acupuncture group was about 4 units less than the sham group, and in the conservative group at this time, the average pain hour was about 1 unit less than sham. The difference between the groups was statistically significant (p<0.0001) (Table 2). The same test also showed that the average pain reduction in the conservative group was significantly (p<0.0001) higher than the sham group.

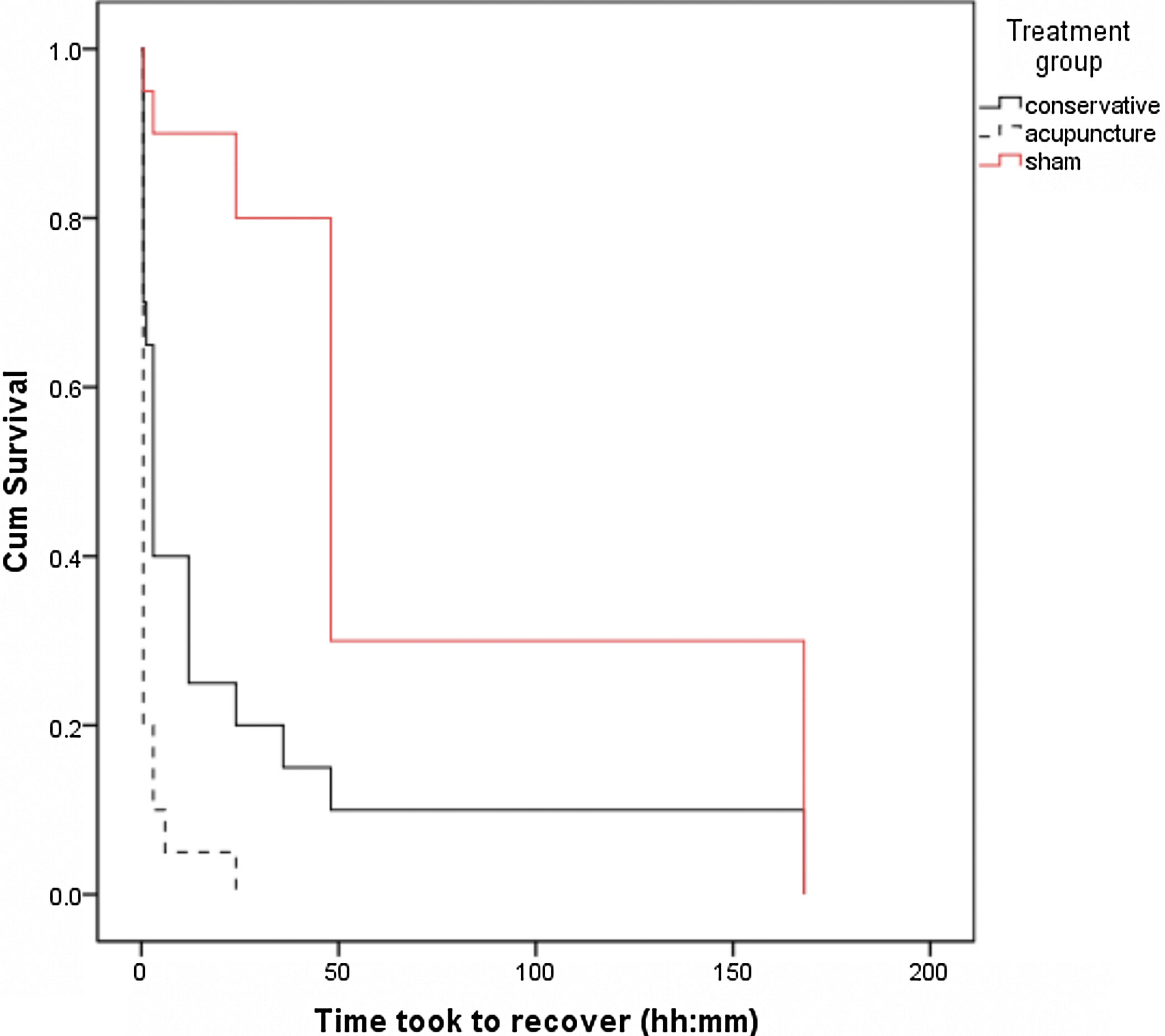

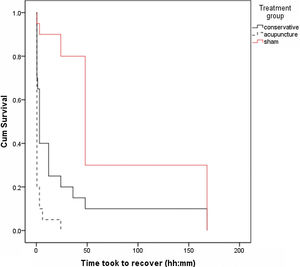

Time to treat painWe evaluated the time taken to reach from moderate to mild (0–3 on VAS) pain in the three roups. In group A, it took 25.1±11.3h, in group B 2.0±1.0h, and in group C it took 14.0±1.77h to reach the scale of mild-to-no headache. Survival analysis and Kaplan–Meier test showed that this time was significantly the shortest in acupuncture group (group B), p<0.001. Also, the time duration of pain reduction in the conservative group was significantly (p<0.0001) shorter than the sham group. Overall, after 7 days, all groups had reach pain scale of 0–3 (Fig. 2).

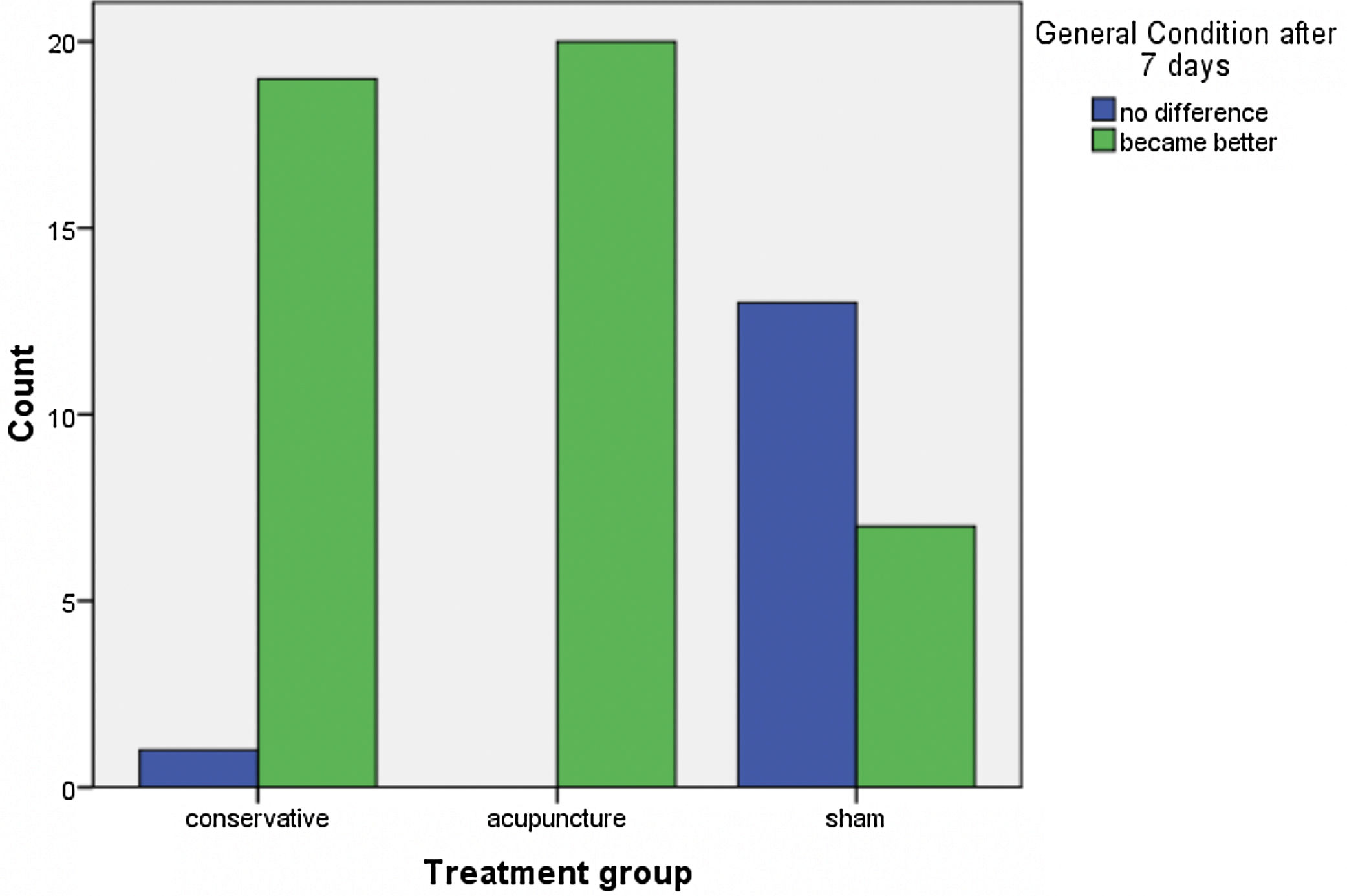

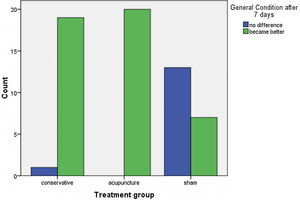

General condition of the patientAs seen in Table 1, the overall condition of the patient in group A and B was not significantly different after 7 days, p=0.2. However, compared to sham group, the overall condition was significantly better in group A and B, p<0.05 (Fig. 3).

DiscussionOur study is the first study to report the therapeutic effects of acupuncture on postdural puncture headache. The findings of our study reported that acupuncture is more effective and faster to treat headache following spinal anesthesia as compared to conservative treatment using analgesics.

Headache after spinal anesthesia (or low-pressure headache) is usually a vague or burning headache that can be accompanied by dizziness, nausea and vomiting, neck and back pain and sensitivity to light and auditory signals.14 Symptoms worsen when standing or moving, and improve slightly in the supine position. PDPH may be associated with cerebrospinal fluid loss during puncture.15 Common therapeutic approaches include adequate fluid intake, normal oral analgesia, and caffeine anti-migraine treatments.16 Epidural blood patch is also used for the purpose, however, similar to other pharmacological agents, it is associated with side effects.17 Acupuncture has been used successfully to treat headache with various etiologies (migraine, cluster, tension, and chronic type without classification).18

All the patients in our study were presented with PDPH due to spinal anesthesia. Routine needles were used for spinal anesthesia and initial intensity of the headache was not significant among the patients. The patients were thereby, provided three different types of interventions; conservative treatment, acupuncture and acupuncture placebo or sham. In our center, following spinal anesthesia, patients presented with mild headache based on VAS score, are provided with conservative treatment and those provided with severe headache are treated with epidural blood patch. Blood patch is also used among patients with moderate headache where in the cases of dissatisfaction, acupuncture is recommended.

For analgesic effects of acupuncture, needles are inserted and manipulated to restore the flow of energy (QI) along the body channels (Meridians). In Western medicine, acupuncture is based on the principles of neurophysiology, in which the insertion of acupuncture needles releases endorphins and regulates pain pathways. Acupuncture points are selected based on the patient's signs and symptoms.6

A case report on patients reported the use acupuncture to treat PDPH among patients who underwent surgical procedure under spinal anesthesia. Before acupuncture, the patients had VAS score 7–8 and significant reduction in the pain was seen few minutes following the acupuncture.12 Similarly, Perera19 reported the use of acupuncture to treat postdural headache among elective cesarean section patients.

Dietzel, Witstruck20 presented five case studies of female patients presented with headache following epidural anesthesia. All the patients reported a significant decrease in the pain following acupuncture and the dose and need of analgesic were reduced. Our study compares the effects of analgesics against acupuncture to treat PDPH. The findings of our study are in line with these case reports.

Acupuncture techniques target muscle spasm (neck stiffness and band-like tightening) as well as tender points along the gall bladder meridian with general relaxation and analgesic points. In the Perara study, 4 out of 6 patients remained asymptomatic after one initial treatment session. However, the various studies included a small number of cases and were not fully explained, so interpreting the data was difficult. In our study, the sample size was appropriate (20 cases per group) and the design of the study was RCT, so the results can be justified.

Sharma and Cheam14 reported two cases of low-pressure post-partum headache due to aneuraxial labor analgesia where patients had pain score of 3 and 7–9, respectively. The pain in these patients were successfully managed by acupuncture in two days.

Acupuncture is relatively safe and minimally invasive if performed by specialists. It is a simple and easy-to-learn technique.19 Many patients feel relaxed after acupuncture.21 The risks and side effects of acupuncture are small and usually insignificant.22 It may cause drowsiness or lightheadedness after treatment and in some cases, can cause vasovagal attack, especially in those who are needle-phobic.23 Studies by Huei-chi horing and Jo DJ. Lee reported the development of PDPH after treatment for lower back pain by acupuncture due to the use of a long needle.24,25

ConclusionDuring our study, one patient acquired severe pain and was treated with blood patch. According to the results of our study, acupuncture may be effective, less invasive, and effective for PDPH. The cost is very low, and patients are usually relaxed and satisfied.9 Blood patching is an invasive procedure that requires skill. Special precautions should be taken as it is not routinely performed in the ward. Blood patch may cause infection and secondary dural puncture may occur.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestThe authors deny any conflict of interest in any terms or by any means during the study.

The study was approved by the Board of Ethical Committee of Imam Reza Hospital.