Klinefelter syndrome is the most frequently found aneuploidy among male patients. Its clinical presentation is very heterogeneous, and thus poses a challenge for a timely diagnosis.

MethodsA retrospective study was carried out with 51 consecutively selected patients diagnosed with Klinefelter Syndrome from Jan/2010 to Dec/2019. The karyotypes were identified using high resolution GTL banding at the Genetics Department. Multiple clinical and sociological parameters were studied by collecting data from the clinical records.

Results44 (86%) of the 51 patients presented a classical karyotype (47,XXY) and 7 (14%) showed evidence of mosaicism. The mean age at diagnosis was 30.2±14.3 years old. Regarding the level of education (N=44), 26 patients (59.1%) had no secondary education, with 5 (11.4%) patients having concluded university studies. Almost two thirds of the sample revealed learning difficulties (25/38) and some degree of intellectual disability was present in 13.6% (6/44). Half of the patients were either non-qualified workers (19.6%) or workers in industry, construction, and trades (30.4%), which are jobs that characteristically require a low level of education. The proportion of unemployed patients was 6.5%. The main complaints were infertility (54.2%), followed by hypogonadism-related issues (18.7%) and gynecomastia (8.3%). 10 patients (23.8%, N=42) were biological parents. With regards the question of fertility, assisted reproductive techniques were used in 39.6% of the studied subjects (N=48), with a success rate (a take home baby) of 57.9% (11/19), 2 with donor sperm and 9 with the patients’ own gametes. Only 41% of the patients (17/41) were treated with testosterone.

ConclusionThis study identifies the most important clinical and sociological findings of Klinefelter syndrome patients that should be considered when deciding workout and disease management.

El síndrome de Klinefelter es la aneuploidía más frecuente entre los pacientes varones. Su presentación clínica es muy heterogénea, por lo que supone un reto para su diagnóstico oportuno.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio retrospectivo con 51 pacientes seleccionados consecutivamente con diagnóstico de Síndrome de Klinefelter desde enero de 2010 hasta diciembre de 2019. Los cariotipos se identificaron mediante bandeo GTL de alta resolución en el Departamento de Genética. Se estudiaron múltiples parámetros clínicos y sociológicos mediante la recogida de datos de las historias clínicas.

ResultadosDe los 51 pacientes, 44 (86%) presentaron un cariotipo clásico (47,XXY) y siete (14%) evidenciaron mosaicismo. La edad media al diagnóstico fue de 30,2 ± 14,3 años. En cuanto al nivel de estudios (n = 44), 26 pacientes (59,1%) no tenían estudios secundarios, y cinco (11,4%) habían concluido estudios universitarios. Casi dos tercios de la muestra revelaban dificultades de aprendizaje (25/38) y algún grado de discapacidad intelectual estaba presente en 13,6% (6/44). La mitad de los pacientes eran trabajadores no cualificados (19,6%) o trabajadores de la industria, la construcción y los oficios (30,4%), que son empleos que característicamente requieren un bajo nivel educativo. La proporción de pacientes en paro era de 6,5%. Las principales quejas eran la infertilidad (54,2%), seguida de problemas relacionados con el hipogonadismo (18,7%) y la ginecomastia (8,3%); 10 pacientes (23,8%, n = 42) eran padres biológicos. En cuanto a la cuestión de la fertilidad, se utilizaron técnicas de reproducción asistida en 39,6% de los sujetos estudiados (n = 48), con una tasa de éxito (un bebé para llevar a casa) de 57,9% (11/19), dos con semen de donante y nueve con gametos propios de los pacientes. Solo 41% de los pacientes (17/41) fueron tratadas con testosterona.

ConclusionesEste estudio identifica los hallazgos clínicos y sociológicos más importantes de los pacientes con síndrome de Klinefelter que deben tenerse en cuenta a la hora de decidir el tratamiento y el manejo de la enfermedad.

Klinefelter syndrome (KS) is the most frequent aneuploidy among male patients, with an estimated prevalence of 152 per 100,000 live-born males.1 It was first reported in 1942 by Klinefelter et al., who described a group of 9 patients with hypogonadism, azoospermia, gynecomastia, and high levels of plasmatic follicle stimulating hormone (FSH). The cornerstone of their diagnosis is the karyotype study, which shows a 47, XXY chromosome complement in approximately 90% of the cases. The rest of the patients present mosaicisms (i.e., 46XY/47XXY or 46XY/45X/47XXY), structural abnormalities [i.e., 47,XX,der(Y), 47,XY,der(X),] and chromosomal aneuploidies with two or more extra chromosomes (48XXXY and 49XXXXY).2,3 The clinical presentation of KS is very heterogeneous, even in the presence of the same karyotype, ranging from no signs and symptoms to a phenotype comprising sexual alterations (in the context of hypergonadotropic hypogonadism), infertility, obesity, development delay, neurological/psychiatric disturbances, and learning difficulties, among other symptoms.4,5 Most KS cases are not diagnosed during lifetime,6 and, for this reason, it is essential to know who these patients are from a clinical and social perspective, in order to increase the chance of diagnosis. Considering that a limited literature exists on KS in Portugal,7 the objective of this study was to clarify the clinical and sociological characteristics of patients who have this syndrome.

MethodsWe conducted a retrospective study of 51 consecutively selected patients who had been diagnosed with KS from January 2010 to December 2019. All the patients presented a karyotype (performed in the genetics department of the Faculty of Medicine of our hospital) with an X-chromosome polysomy and at least one Y chromosome, either as a pure lineage, or as a mosaicism. At least 30 metaphases were analyzed during our karyotype study.

We collected data by searching patient clinical records. We studied multiple clinical and sociological parameters, such as: the type of karyotype, anthropometric measures, age at diagnosis, marital status, profession, level of education, learning difficulties, intellectual disability, anxiety/depression issues, complains of sexual dysfunction, gynecomastia, and incomplete development of secondary sexual characteristics. In addition, we also studied the reasons that motivated the etiological study, including: spermogram characteristics, paternity issues, assisted reproductive techniques, tobacco and alcohol consumption, analytical parameter at diagnosis (Luteinizing hormone – LH, FSH and total testosterone), anthropometric measures (body mass index – BMI), and the proportion of patients who were medicated with testosterone/being followed with an endocrinological consultation. Clinical data of the recorded files was complemented, in those cases with missing information, with data obtained through telephonic contact with the patients (mainly regarding sociological features such as current marital status, profession, scholar education and reasons that motivated diagnostic workout).

We considered that a patient who had undergone fertility treatment when submitted to a testicular biopsy with viable spermatozoa extraction, followed by intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) techniques; or when the patient opted to use donor sperm to conceive. Patients who had undergone testicular biopsy with no viable gametes were not considered to have been subject to fertility treatment. A patient was considered to have learning difficulties if they had failed a school year, or if they had any clinical records regarding this issue. Depression or intellectual disabilities were also considered if a patient presented any reference to suffering from these disturbances in their records. The conditions classified as “hypogonadism” in the reasons that motivated diagnostic workout were considered to be those related with sexual disfunction (e.g., low libido or sexual disfunction) and those encompassing delays in secondary sexual characteristics development.

Statistical analyses were performed with the use of SPSS Statistics 26® software. Categorical variables are presented as the number of individuals followed by their proportion (in percentage) included in each category. Continuous variables (such as BMI, LH and FSH) are presented as means and standard deviations.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for health of our hospital.

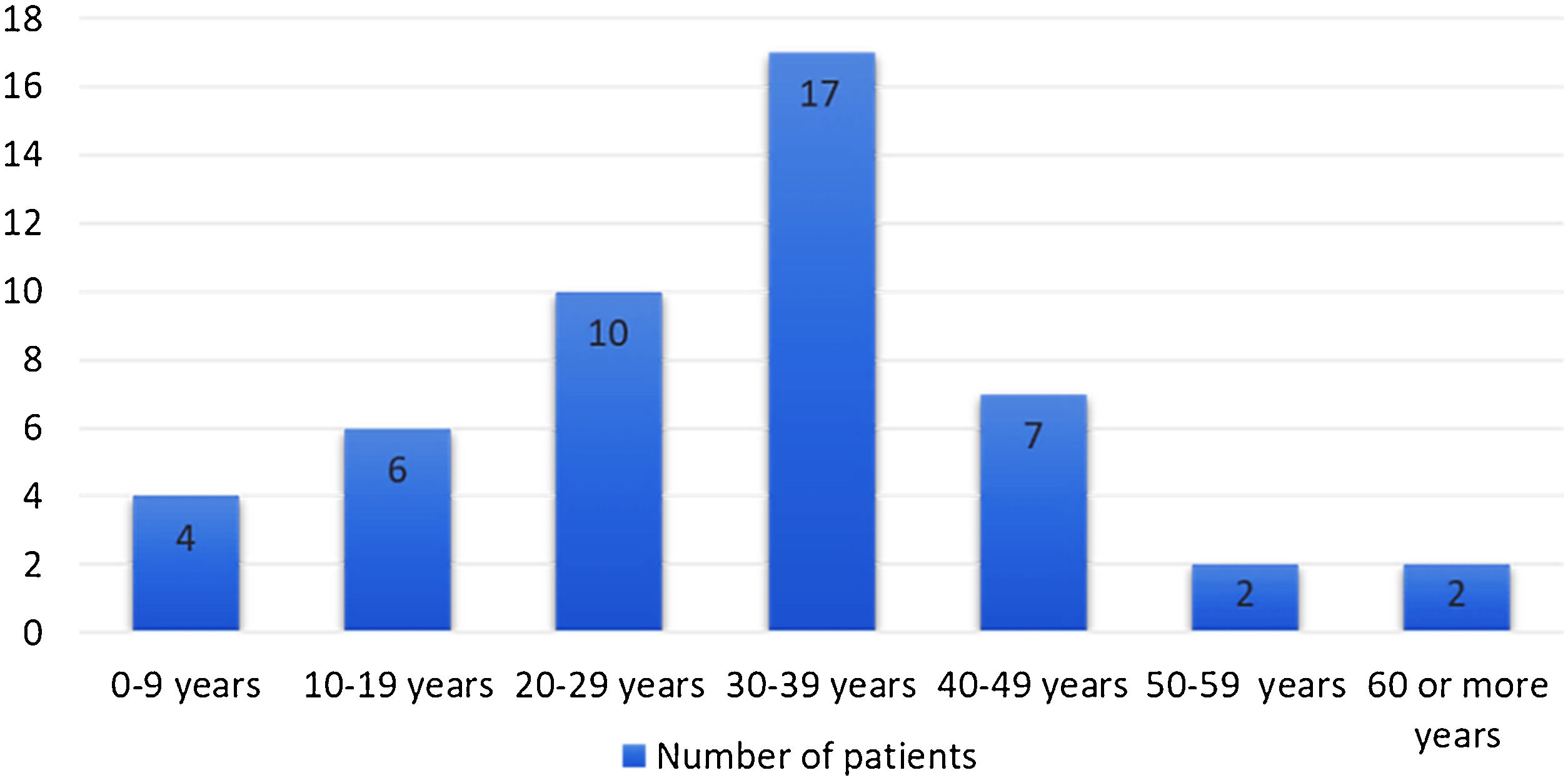

ResultsForty-four (86.3%) of the 51 patients presented a classical karyotype (47,XXY) and 7 (13.7%) showed evidence of mosaicism. Among these mosaic patients, the karyotype was 47,XXY/46,XY in six of them, and 47,XXY/46,XY/45,X in the other one. Eight of the 48 patients (16.7%) were aged under 18 years old when the diagnosis was made. A prenatal diagnosis was made in one case (2.1%) and four cases (8.3%) were aged 50 or more at the time of diagnosis. Most cases were aged 30–39 years at diagnosis, with more than 50% of the patients being diagnosed during the 3rd and 4th decades of life (Fig. 1). Of the 47 patients for whom information regarding their marital status was obtained, 27 (57%) were married, 13 (28%) were single, 4 (9%) were in a ‘de facto union’, and 3 (6%) were divorced. Regarding the level of education (N=44), 26 patients (59.1%) had not achieved secondary education, with only 5 of them (11.4%) having concluded university studies. Almost two thirds of the studied subjects revealed learning difficulties (25 out of 38) and some degree of intellectual disability was mentioned in the clinical records of 13.6% of the sample (6 out of 44). A history of tobacco consumption was referred to for almost half of the patients (20 out of 42), while alcohol abuse was present in 9.5% of them. Half of the patients were either non-qualified workers (19.6%) or qualified workers in industry, construction, or trades (30.4%), usually in jobs requiring a low level of education. The proportion of unemployed patients was 6.5%. KS was diagnosed in the context of infertility in most patients (54.2%), followed by complains related with hypogonadism (18.7%) and gynecomastia (8.3%). Biological paternity was achieved in 10 out of 42 patients (23.8%), although in 8 of these 10 cases this was the result of assisted reproductive techniques. These techniques were used in 43.2% of the studied subjects (the majority using their own spermatozoa), with a success rate of 57.9% (11 out of 19). Of these 11, 2 of the four patients (50%) who achieved paternity did so with donor sperm, with the other 9 patients using their own spermatozoa (9 out of 15, 60%). A spermogram revealed azoospermia in more than 90% of patients (28 out of 31). A BMI of between 25 and 29.9kg/m2 was presented by 18 patients (51.4%), and 4 (11.5%) had obesity (Note: 45.4% of the Portuguese male population is overweight, while 24.9% has obesity).8 Lower segment, upper segment, and arm span data are not presented, because this clinical information was only obtained for very of the few patients.

Regarding analytical parameters at the time of diagnosis, the results revealed elevated levels of LH in 89.3% of the patients (19.8±9.7, N=28), with increased levels of FSH in 100% of the patients under study (31.4±13.1, N=25). The level of total testosterone was reduced in 57.1% of the sample (2.7±2.2; N=28). Only 41% of the patients (17 out of 41) were treated with testosterone (usually via intramuscular administration – see Table 1).

Clinical and sociological characteristics of the patients under study.

| Parameter | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Marital status (N=47) | |

| Married | 27 (57.4) |

| De facto union | 4 (8.5) |

| Single | 13 (27.7) |

| Divorced | 3 (6.4) |

| Scholar education (N=44) | |

| 0–4th grade | 6 (13.6) |

| 5–6th grade | 8 (18.2) |

| 7–9th grade | 12 (27.3) |

| 10–12th grade | 13 (29.5) |

| Graduate/Master's degree | 4 (9.1) |

| Doctorate | 1 (2.3) |

| Learning difficulties (N=38) | 25 (65.8) |

| Intellectual disability (N=44) | 6 (13.6) |

| Depression/anxiety problems (N=41) | 20 (48.8) |

| Tobacco consumption (N=42) | |

| Smoker | 14 (33.3) |

| Ex-smoker | 6 (14.3) |

| No history of tobacco consumption | 22 (52.4) |

| Alcohol abuse (N=42) | 4 (9.5) |

| Profession (N=46) | |

| Qualified workers of industry, construction, and trade | 14 (30.4) |

| Non-qualified workers | 9 (19.6) |

| Student | 5 (10.9) |

| Unemployed | 3 (6.5) |

| Social-service related jobs/security area and Salesmen | 3 (6.5) |

| Scientific/intellectual specialists | 3 (6.5) |

| Technicians and intermediate-level professions | 2 (4.3) |

| Directors and Executive Managers | 2 (4.3) |

| Machine/installation operators and Assembly Workers | 2 (4.3) |

| Retired | 2 (4.3) |

| Armed forces related jobs | 1 (2.2) |

| Reason that motivated diagnostic workout (N=48) | |

| Infertility | 26 (54.2) |

| Hypogonadism | 9 (18.7) |

| Gynecomastia | 4 (8.3) |

| Psychomotor development delay | 3 (6.2) |

| Learning difficulties | 2 (4.2) |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 2 (4.2) |

| Obesity | 2 (4.2) |

| Gynecomastia (N=41) | 18 (43.9) |

| Incomplete secondary sex characteristic development (N=30) | 20 (66.7) |

| Microorquidism (N=42) | 36 (85.7) |

| Sexual disfunction (N=36) | 14 (38.9) |

| Paternity (N=42) | |

| No | 26 (61.9) |

| Biological father | 11 (26.2) |

| Adoptive father | 3 (7.1) |

| Father after recurring to donor sperm | 2 (4.8) |

| Spermogram (N=31) | |

| Azoospermia/Oligospermia | 28 (90.3) |

| Impaired mobility of the spermatozoa | 1 (3.2) |

| No alterations | 2 (6.5) |

| Assisted reproductive treatments (N=44) | |

| No | 25 (56.8) |

| Yes, with donor sperm | 4 (9.1) |

| Yes, with the patient's own spermatozoa | 15 (34.1) |

| Testosterone treatment (N=41) | 14 (41.5) |

This observational study was designed to identify the main characteristics of those patients with KS in our hospital. The majority of the 51 patients in the sample presented the classical phenotype 47,XXY (86.3%), which is in line with previous data that shows that the proportion of this particular karyotype lies between 80 and 90% of total subjects.5,9–11 It is also important to highlight that 83.3% of the patients for who information was collected regarding the age at diagnosis were diagnosed during adulthood, with 4 of them only discovering that they had KS when they were aged 50, or more. This proportion is higher than previous studies on the issue of KS, such as that of the Danish cohort described by Aksglaede et al. (47.0% of the 166 patients were adults),12 or the Indian cohort from Asirvatham et al. (61.4% of 44 KS patients),13 although it is in line with the study from Brazil (where only 21% were diagnosed before the age of 20).14 The late age at diagnosis among our cohort of patients should raise awareness of this syndrome and points to the importance of maintain a high level of suspicion if a successful diagnostic approach is to be achieved (mainly among young individuals). The reason that led to the diagnostic of KS in most of our patients was infertility (54.2% of all patients and 65% of patients diagnosed as an adult). Once again, this could be related with the absence of a distinct phenotype in many of the patients, leading to a low frequency of KS diagnosis at younger ages and to the detection of this syndrome only when patients want to be parents. This is in line with the studies such as that of Aksglaede et al., which showed that 67.7% of individuals diagnosed during adulthood were infertile (46 of 68 patients with classical phenotype).12 The other recently published study on KS in Portugal by Barbosa et al. found different results, where gynecomastia was the main motive for referencing these patients for endocrinology consultation (31.3% of all cases). This can be explained, at least partially, by the smaller sample size (composed of 16 patients) of this study.15 Regarding the professional occupations of our KS patients, we verified that 50% of them had jobs that required a low level of differentiation/education, and that 6.5% were unemployed. We found that no other report in the literature addresses this important aspect of KS lives. These results could be associated with an increased proportion of learning difficulties (65.8%) and a certain degree of intellectual disability for 13.6% of the patients with KS (which is also related with their academic performance – 59.1% did not achieve secondary studies). The neuropsychological phenotype of the patients with KS varies greatly. Despite this fact, the most consistent findings in the literature are: impaired verbal skills, an increased incidence of dyslexia, and dysfunctions in social behaviour. These factors should motivate the need to prescribe speech and language therapy and specialized help at school for those patients diagnosed during a young age.16 These learning and social difficulties count among the various sources of anxiety and depression, which represent two of the most frequent and debilitating symptoms of KS.2 Almost half of the patients under study (48.8%) reported a history of mood disturbances, together with depression and/or anxiety. Previous data regarding this issue reported that approximately 18% of KS patients have generalized anxiety, and that 19–24% have clinical depression, with 68% of KS individuals reporting depressive symptoms.17 One of the main issues among KS patients is the question of fertility and paternity.18 Our study demonstrated that almost 25% of the patients under study achieved biological paternity, and that the success rate of assisted reproductive techniques was 57.9%. A previous meta-analysis of 29 trials by Corona et al.6 reported that a total number of 218 biochemical pregnancies were achieved after 410 intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles (pregnancy rate=43%). Similar results were observed when live birth rate per ICSI cycle was analyzed (211 live births).19 We acknowledge that the proportions of our patients with fertility problems is unexpectedly high for KS patients when compared with previous existent data, especially regarding those achieving paternity with their own spermatozoa. One explanation for these findings could be the low number of individuals submitted to assisted reproductive techniques in our group of patients (only 19 patients). Other important aspect is that the process regarding reproductive techniques or adoption is not detailed in the clinical files, and, for this reason, the clinician following the patient needs to ask them about this issue. This can lead obviously to an overestimation of the proportion related with parenthood (especially biological parenthood), as the patient might feel more prone to tell the doctor that a child was conceived with their own spermatozoa, rather than with donor sperm. In addition, 2 of the 11 patients claiming biological parenthood conceived without assisted reproductive techniques, even though they presented a classical phenotype (47,XXY). Considering the difficulties that these patients face in conceiving (even with medical assistance), the authors believe that these two particular cases should be interpreted with caution.

Finally, we would like to highlight the surprising low proportion of KS patients who had been treated with testosterone in our study sample (41%). The causes for this phenomenon seem to be the low referral from the endocrinology department, the abandoning of endocrinology consultations by some patients, and the precarious interdisciplinary dialogue. These results should raise some questions about how KS patients are being followed in Portugal, leading us to find different solutions to maximize health and quality of life and to avoid undertreatment.

This study presents some limitations, one being its retrospective design. Some information was collected through telephonic contact with the patients, which is a factor that needs to be considered when interpreting the results. Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this research presents the biggest sample analysis to date of KS patients being followed in Portugal. In addition, it combines clinical and sociological factors in the same study, giving a broad picture of the patients that could be another useful tool for the management of patients who have this disease. Finally, our research reinforces the hypothesis that a long-term multidisciplinary approach to KS patients is required, based on the complex and heterogeneous presentation of KS, that combines the expertise of medical areas such as endocrinology, paediatrics, psychology/psychiatry, and urology, among others.1

ConclusionThis study represents the most important clinical and sociological findings of KS patients in Portugal, which should be considered during the diagnostic analysis of patients and disease management. Gaining knowing about these factors would be important for the promotion of health and the quality of life of KS patients, which would also avoid inefficient treatment.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Ethical approvalAll the procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the hospital and/or national research committee and are in compliance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consentThe need for informed consent was waived by the local ethics committee.

Grant supportThere is no grant support to declare.

FundingThere is no funding to declare.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.