Transient ejaculation failure can be seen on the oocyte retrieval day which might cause the cancelation of oocyte retrieval procedure. The aim of this study was to evaluate the management of these patients and to assess the clinical outcome of intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) using spermatozoa obtained from them.

MethodsThe records of the oocyte pick-up (OPU) procedures between November 2014 and January 2017 were reviewed, the management and ICSI outcomes of 26 patients with transient ejaculation failure due to erectile difficulties on the oocyte retrieval day were evaluated.

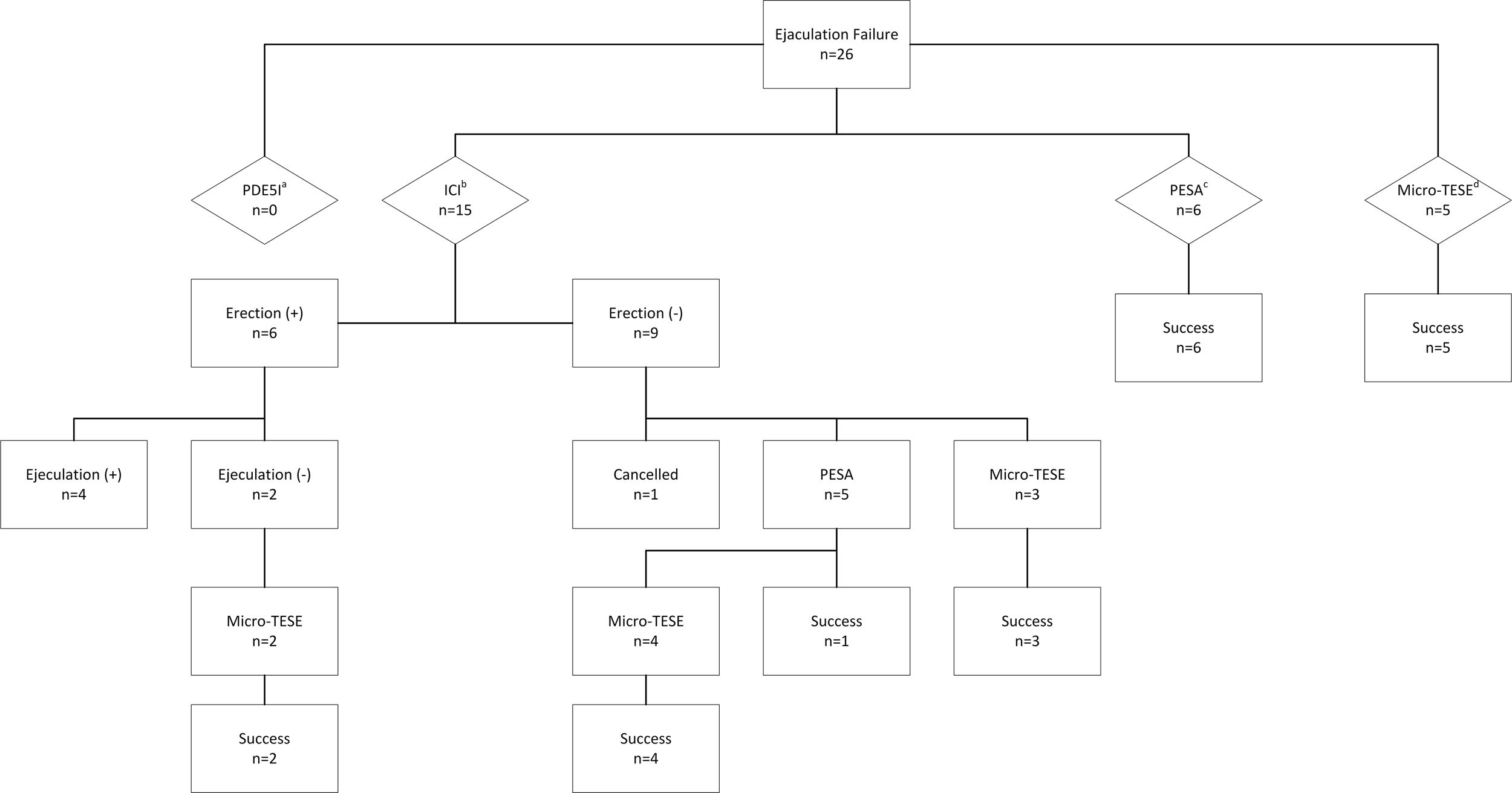

ResultsIntracavernosal injection (ICI), percutaneous sperm aspiration (PESA) and microdissection testicular sperm extraction (micro-TESE) were performed to 15, 6 and 5 patients, respectively. The sperm retrieval rate (SRR) and live birth rate (LBR) of ICI, PESA and micro-TESE were 26%, 63.6% and 100% and 40%, 16.7%, 38.4% respectively.

ConclusionsAlthough a limited number of cases were evaluated in this study, micro-TESE appears to be the preferable approach when assessed both in terms of sperm retrieval method success and ICSI results.

Se puede observar una incapacidad transitoria para eyacular el día de la recuperación de oocitos, que podría provocar la anulación del procedimiento. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar el tratamiento de estos pacientes y el resultado clínico de la inyección intracitoplasmática de espermatozoides (IICE) con espermatozoides propios.

MétodosSe revisaron las historias clínicas de procedimientos de aspiración de oocitos (OPU) entre noviembre de 2014 y enero de 2017, se evaluaron el tratamiento y los resultados de la IICE en 26 pacientes con incapacidad temporal para eyacular a causa de dificultades eréctiles el día de recuperación de oocitos.

ResultadosLa inyección intracavernosa (ICI), la aspiración percutánea de espermatozoides del epidídimo (PESA) y la microcirugía para la extracción de espermatozoides testiculares (micro-TESE) se realizaron a 15, 6 y 5 pacientes, respectivamente. La tasa de recuperación de espermatozoides (SRR) y la tasa de recién nacidos vivos (LBR) de ICI, PESA y micro-TESE fueron del 26, del 63,6 y del 100%, por una parte, y del 40, del 16,7 y del 38,4%, respectivamente.

ConclusionesAunque se ha analizado un número limitado de casos en este estudio, parece que la micro-TESE es el enfoque preferible cuando se evalúa tanto el éxito del método de recuperación de espermatozoides como el de los resultados de la IICE.

The process of in vitro fertilization (IVF) can be physically and emotionally stressful for the infertile couples.1 In this process, the male partner's role is to produce spermatozoa as well as to support his partner.2 However, the male partners may experience transient ejaculation failure on the day of oocyte retrieval due to physiological and psychological reasons and if sperm cannot be obtained, the couples face the risk of cancelation of the oocyte retrieval procedure.3 Resorting to cryopreservation of the oocytes or sperm donation would be the only possibilities to overcome this situation. However, cryopreservation of oocytes and the use of donor spermatozoa may not be in compliance with the legislation and laws of some countries including ours.3,4

In the previous reports, several methods, including sildenafil use, prostatic massage, electroejaculation and surgical retrieval of sperm have successfully been used to help this group of patients.3,5–9 However, almost all of these studies are case reports.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the management of patients experiencing a transient ejaculation failure due to sexual arousal difficulties on the day of oocyte retrieval and the clinical outcome of ICSI using spermatozoa obtained from these patients.

MethodsPatientsWe retrospectively reviewed the records of the oocyte pick-up (OPU) procedures performed between November 2014 and January 2017 and evaluated the management and ICSI outcomes of 26 patients with ejaculation failure due to erectile difficulties on the day of oocyte retrieval treated between November 2014 and January 2017. All patients made the attempt to give sperm samples after 2–7 days of sexual abstinence in a specially designated room in our embryology laboratory, with the aid of audiovisual stimulation. The baseline clinical evaluation for each patient included a comprehensive history and a complete physical examination. All patients had a normal semen analysis according to the World Health Organization criteria10 and there was no history of either erectile dysfunction or anorgasmia before the day of oocyte retrieval.

All patients were informed treatment options including the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, intracavernosal injection (ICI) of papaverine, percutaneous sperm aspiration (PESA) and microdissection testicular sperm extraction (micro-TESE). Of the 26 patients, 15 chose ICI of papaverine, 6 preferred PESA and 5 preferred micro-TESE (Fig. 1). Informed consent form was obtained from all patients before each procedure commenced. The study was approved by Baskent University Institutional Review Board (Project no: KA17/363) and was supported by Baskent University Research Fund.

ICI was performed according to the technique previously reported by Linet et al.11 After 60mg intracavernosal papaverine (Papaverin HCl, Galen, Turkey) injection, pressure was applied to the injection site until bleeding stopped. All patients had audiovisual stimulation to achieve erection. All patients were informed about the risk of priapism.

PESA techniquePESA was performed under local anesthesia according to the technique previously described by Craft et al.12 When a sufficient number of spermatozoa had been retrieved for ICSI, PESA was terminated. When it was not able to extract spermatozoa from one side, the aspiration was repeated on the contralateral epididymis.

Micro-TESE techniqueMicro-TESE was performed according to the technique previously described under sedoanalgesia and/or local anesthesia.13,14 After the mini incision made in the tunica, more opaque and larger seminiferous tubules were selected, removed under magnification with an operating microscope. These tubules were evaluated by an embryologist. When a sufficient number of spermatozoa has been retrieved, micro-TESE was terminated.

Sperm preparationIn ejaculated sperm group, ejaculate samples of the patients were treated with density gradient centrifugation using SupraSperm (Origio, Malov, Denmark) after liquefaction. This discontinuous density gradient in conical tube (Falcon 2095, Falcon Plastics, Belgium) consisted of two (80% and 55%) 1mL layers of SupraSperm (Origio) medium. After the addition of ejaculate onto the 55% layer, the gradient was centrifuged. After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed. The sperm pellet was washed twice with 5mL of Sperm Preparation Medium (Origio, Malov, Denmark). The sperm pellet was resuspended with 1mL of Universal IVF Medium (Origio, Malov, Denmark) and placed in the incubator until the time of ICSI.

In epididymal sperm group, the aspirated epididymal fluid into the syringe filled with 2mL HEPES buffered medium (Quinn's Advantage medium with HEPES, SAGE, USA and Human serum albumin, SAGE, USA) transferred to the Petri dish (Falcon Plastics, Belgium). Evaluation of the wet preparation was performed under an inverted microscope (Olympus IX71, Tokyo, Japan) by experienced embryologists. In patients with spermatozoa present, medium was transferred to the conical tube and centrifuged. Following disposal of supernatant fluid, the sample was resuspended in 0.5mL of medium and placed in the incubator until the time of ICSI.

In testicular sperm group, the testicular tissues in the Petri dish filled with 3mL HEPES buffered medium (SAGE) were prepared according to mechanical technique.15 Evaluation of the wet preparation was performed under an inverted microscope by experienced embryologists. After verification of the presence of spermatozoa, the mixture of tissue and medium was transferred to the conical tube and centrifuged. The supernatant fluid was removed. The final sample was resuspended in 0.2mL of medium and placed in the incubator until the time of ICSI.

Ovarian stimulationOvarian stimulation was performed with either to the agonist or antagonist protocol according to previously reported studies.16 The ovarian stimulation was induced using urinary hCG (Pregnyl, Merck Sharpe Dome, The Netherlands) or a recombinant hCG (choriogonadotropin-alfa, Ovitrelle, Merck Sereno, Italy). In frozen-thawed ICSI cycles, endometrial preparation was done with daily 6mg estradiol oral tablet (Estrofem, Novo Nordisk, Australia). When endometrial thickness reached 8mm, luteal support was started with either progesterone capsule (Progestan, Kocak, Turkey), three times in a day or daily vaginal progesterone gel (Crinone gel 8%, MerckSereno, Italy).

OPU technique and ICSITransvaginal ultrasound-guided OPU was performed under sedoanalgesia. Metaphase II (MII) oocytes were selected and prepared for ICSI. ICSI was performed as described previously.16,17 Embryo grading was done according to the Istanbul consensus on embryo assessment.18 All embryos were transferred with a transfer catheter (Cook Medical Inc, USA) on 2–5 days after ICSI.

Data interpretationAge, infertility period, history of varicocelectomy, sperm retrieval rate (SRR), fertilization rate (FR), implantation rate (IR), clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) and live birth rate (LBR) were determined. FR was calculated as the percentage of the number of fertilized oocytes per number of MII oocytes that have undergone ICSI. IR was calculated by dividing the number of gestational sacs by the number of transferred embryos. Miscarriage rate was calculated by dividing the number of spontaneous pregnancy losses before 20 weeks of gestation by the total number of pregnancies.19 Clinical pregnancy was regarded as presence of intrauterine gestational sac with fetal heart beat visualized by ultrasound examination. LBR was defined as the number of deliveries that resulted in a live born neonate, expressed as a percentage of embryo transfers.19

Statistical analysisThe IBM Statistical Package for the Social Science version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analyses. For each continuous variable, Shapiro–Wilk test and histograms were used to check normality.

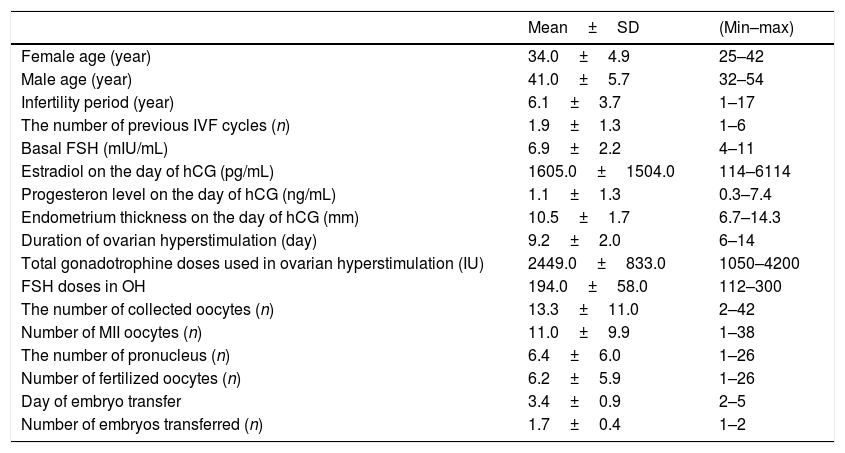

ResultsPatient characteristics3549 OPU procedures were performed during this study period. All patients had no known medical problems. The medical history of the patients revealed varicocelectomy in 7 patients. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Characteristics of intracytoplasmic sperm injection patients.

| Mean±SD | (Min–max) | |

|---|---|---|

| Female age (year) | 34.0±4.9 | 25–42 |

| Male age (year) | 41.0±5.7 | 32–54 |

| Infertility period (year) | 6.1±3.7 | 1–17 |

| The number of previous IVF cycles (n) | 1.9±1.3 | 1–6 |

| Basal FSH (mIU/mL) | 6.9±2.2 | 4–11 |

| Estradiol on the day of hCG (pg/mL) | 1605.0±1504.0 | 114–6114 |

| Progesteron level on the day of hCG (ng/mL) | 1.1±1.3 | 0.3–7.4 |

| Endometrium thickness on the day of hCG (mm) | 10.5±1.7 | 6.7–14.3 |

| Duration of ovarian hyperstimulation (day) | 9.2±2.0 | 6–14 |

| Total gonadotrophine doses used in ovarian hyperstimulation (IU) | 2449.0±833.0 | 1050–4200 |

| FSH doses in OH | 194.0±58.0 | 112–300 |

| The number of collected oocytes (n) | 13.3±11.0 | 2–42 |

| Number of MII oocytes (n) | 11.0±9.9 | 1–38 |

| The number of pronucleus (n) | 6.4±6.0 | 1–26 |

| Number of fertilized oocytes (n) | 6.2±5.9 | 1–26 |

| Day of embryo transfer | 3.4±0.9 | 2–5 |

| Number of embryos transferred (n) | 1.7±0.4 | 1–2 |

n, number; mL, milliliter; mm, millimeter; mIU, milli-international units; pg, picogram; ng, nanogram; hCG, human chorionic gonadotrophin; SD, standard deviation; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; MII, metaphase 2.

Six of 15 patients (40%) had adequate erections after ICI and 2 of these 6 patients could not give a sperm sample for ICSI. Of these 11 patients with erection and ejaculation problems, 5 decided to have PESA and 5 decided to have TESE procedure. The remaining one patient did not want to have another procedure. The OPU procedure was canceled for this couple. In this group, the total number of attempts to obtain spermatozoa was 29 (Fig. 1) and the number of attempts per patient was 1.93.

PESASuitable spermatozoa for ICSI were obtained in 7 of 11 (63.6%) of the patients. In 4 patients in whom PESA failed, simultaneous micro-TESE was performed. The SRR in all patients who initially preferred PESA was 100% (6/6) and the number of attempts per patient was 1.

Micro-TESESuitable spermatozoa for ICSI were recovered in 14 of 14 (100%) of the patients. The SRR in all patients who initially preferred micro-TESE was 100% (5/5) and the number of attempts per patient was 1.

ICSIDemographic and ovarian stimulation parameters are summarized in Table 1.

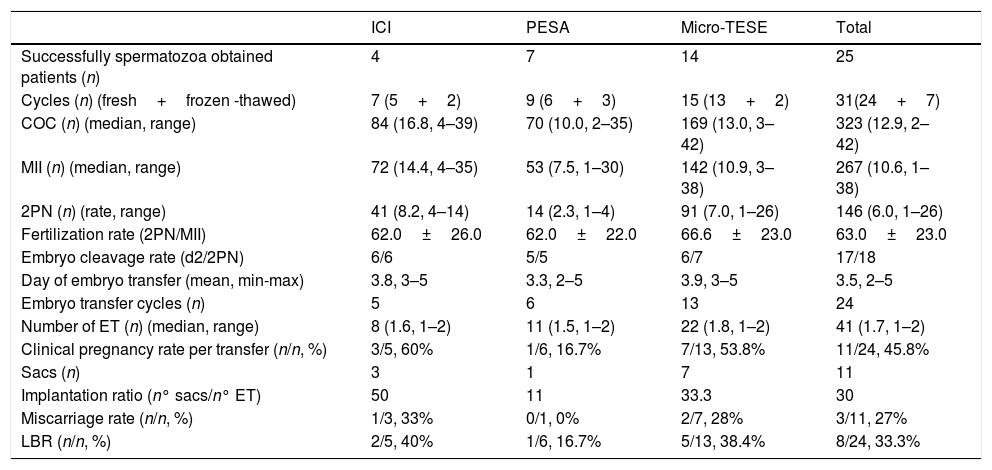

26 male patients who were not able to give sperm on the day of OPU, had 31 ICSI cycles. Among these, embryo transfer was canceled in two cycles because of a high progesterone level above 1.5ng/mL, in two cycles no oocyte was picked up from the follicles, in one cycle embryo did not enter cleavage stage, in one cycle total fertilization failure was encountered and in one cycle due to ovarian hyperstimulation. Embryo transfer was done in the remaining 24 cycles which 21 of them were fresh and 3 of them were frozen-thawed cycles. The pregnancy rates and LBR were different in cycles with different sperm extraction (ICI, PESA, micro-TESE) (Table 2). The pregnancy rates for ICI, PESA and micro-TESE were 60%, 16.7% and 53.8% and the LBR were 40%, 16.7% and 38.4%, respectively.

ICSI and embryological outcomes of patients.

| ICI | PESA | Micro-TESE | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Successfully spermatozoa obtained patients (n) | 4 | 7 | 14 | 25 |

| Cycles (n) (fresh+frozen -thawed) | 7 (5+2) | 9 (6+3) | 15 (13+2) | 31(24+7) |

| COC (n) (median, range) | 84 (16.8, 4–39) | 70 (10.0, 2–35) | 169 (13.0, 3–42) | 323 (12.9, 2–42) |

| MII (n) (median, range) | 72 (14.4, 4–35) | 53 (7.5, 1–30) | 142 (10.9, 3–38) | 267 (10.6, 1–38) |

| 2PN (n) (rate, range) | 41 (8.2, 4–14) | 14 (2.3, 1–4) | 91 (7.0, 1–26) | 146 (6.0, 1–26) |

| Fertilization rate (2PN/MII) | 62.0±26.0 | 62.0±22.0 | 66.6±23.0 | 63.0±23.0 |

| Embryo cleavage rate (d2/2PN) | 6/6 | 5/5 | 6/7 | 17/18 |

| Day of embryo transfer (mean, min-max) | 3.8, 3–5 | 3.3, 2–5 | 3.9, 3–5 | 3.5, 2–5 |

| Embryo transfer cycles (n) | 5 | 6 | 13 | 24 |

| Number of ET (n) (median, range) | 8 (1.6, 1–2) | 11 (1.5, 1–2) | 22 (1.8, 1–2) | 41 (1.7, 1–2) |

| Clinical pregnancy rate per transfer (n/n, %) | 3/5, 60% | 1/6, 16.7% | 7/13, 53.8% | 11/24, 45.8% |

| Sacs (n) | 3 | 1 | 7 | 11 |

| Implantation ratio (n° sacs/n° ET) | 50 | 11 | 33.3 | 30 |

| Miscarriage rate (n/n, %) | 1/3, 33% | 0/1, 0% | 2/7, 28% | 3/11, 27% |

| LBR (n/n, %) | 2/5, 40% | 1/6, 16.7% | 5/13, 38.4% | 8/24, 33.3% |

COC, cumulus-oocyte complexes; MII, metaphase 2 oocytes; PN, two pronuclei; d2, embryos on day 2 after fertilization; ET, embryos transferred; LBR, live birth rate; n, number.

Male partners may experience transient ejaculation failure on the oocyte retrieval day due to social pressure, being in a complex medical procedure and a different environment.3 In such cases, there are several options available, including audiovisual support, sildenafil use, prostatic massage, ICI, PESA and TESE for couples to have their own children.1,3,5–8 If these methods are not successful or cannot be performed, the OPU procedure may have to be canceled.8

Oocyte cryopreservation or sperm donation seem to be alternative solutions for not canceling the OPU procedure.3,4 However, in some countries, legislation and laws do not permit oocyte cryopreservation and the use of donor spermatozoa.

During the study period, 26 cases of unexpected ejaculation failure occurred and a total of 3549 oocyte retrieval cycles were carried out, giving an incidence of 0.73%. Okohue et al. and Junsheng et al. reported the incidence of ejaculation failure on the day of the oocyte retrieval as 1.66% and 1.12%, respectively.1,3 Our incidence may be lower because in our clinic we routinely provide audiovisual support to the patients.

None of our patients agreed the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors. It may be associated with the embarrassment of having to identify themselves as having erectile difficulties.

In our study, the success rate of ICI is low. However, a significant proportion of psychogenic patients do not completely respond to ICI of papaverine or prostaglandin E1.20 Various hypotheses have been proposed to explain this situation. Intense stress linked to the procedure can cause the lack of erectile response to ICI.20 The drugs such as papaverine, prostaglandin E1 or combination therapies can be used for ICI. We used papaverine because in our country, neither prostaglandin E1 nor the combination form is available in the market.

A study by Esteves et al. reported that the SRR with PESA in 146 patients with obstructive azoospermia was 78%.21 In their study, patients were divided into 3 groups according to the etiology of obstruction as congenital bilateral absence of vas deference (CBAVD) group (n=32), vasectomy group (n=59) and post-infection obstruction group (n=55). SRR was 96.8% in the CBAVD group, 69.5% in the vasectomy group and 76.4% in the post-infection obstruction group.21 In patients with obstructive azoospermia, success rates of PESA range from 61% to 100%.22 Our SRR with PESA is similar to the literature.

In patients with transient ejaculation failure on the oocyte retrieval day, TESA may also be a treatment option. Its simplicity and ability to be accomplished with local anesthesia are advantages but the high complication rate and long operative time due to multiple punctures may outweigh the advantages of this blind procedure.23 When we look at it in terms of SRR, TESA is inferior to TESE and micro-TESE.23 Moreover, TESE and micro-TESE can be safely performed under local anesthesia and/or sedoanalgesia. Therefore, we preferred micro-TESE for testicular sperm retrieval.

ICSI was performed by using ejaculated, epididymal and testicular spermatozoa. The overall pregnancy rate was 45.8% and LBR was 33.3%. Although statistical analysis is not possible due to the small number of patients in groups, it is remarkable that the pregnancy rate is low in the PESA group (Table 2). Junsheng et al., who have a similar male population, reported a CPR of 38.83% and an LBR of 29.13%.3

The numbers of attempts per patient according to initial patients’ preferences were 1.93 in ICI group, and 1 for both PESA and micro-TESE groups. Although ICI is less invasive than PESA and micro-TESE, the success rates of the PESA and the micro-TESE were remarkably higher. However, the PR of PESA group was lower than micro-TESE group. Thus, micro-TESE seems to be the preferable method for the patients who experience transient ejaculation failure on the day of oocyte retrieval.

Besides the preference of the couples and the physician, the facilities of the centers and the legal obligations of the countries are also determinants for determining the approach.

This study has some limitations including retrospective nature and small cohort size which caused non-homogenized ICSI parameters. Additionally, the rarity of this acute situation hinders the attempts to design a prospective study.

To the best of our knowledge, the current study of 26 patients is the second largest series of the patients with transient ejaculation failure on the day of oocyte retrieval. Almost all of the other studies in the literature consist of case reports and case series.1,2,4–9 Furthermore, we report the success rates of different sperm retrieval methods and the results of ICSI with sperm obtained with these methods. In our study, micro-TESE appears to be the preferable approach to obtain sperm for ICSI in patients with transient ejaculation failure due to erectile difficulties on the oocyte retrieval day.

ConclusionsThe management of the patients with transient erectile difficulties on the day of oocyte retrieval may be challenging. There are several treatment options however, the choice of the optimal treatment is unclear. In addition, some countries have legal limitations such as the restriction of oocyte cryopreservation and sperm donation. The preference of the couples and the physician, the facilities of the centers and the legal obligations of the countries are also determinants for determining the treatment choice.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

FundingThis research was supported by Baskent University Research Fund.

Conflicts of interestAll authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.