To evaluate the quality of information in You Tube videos pertaining to premature ejaculation.

Materials and methodsA search for “premature ejaculation” (PE) was performed on You Tube in August 2018. Two senior urologist viewers watched and categorized each video for their sources, suggestions and information contents (excellent, fair or poor).

ResultsOf the three hundred videos viewed on You Tube, 155 videos were included and analyzed. Mean video length (mean±standard deviation) was 3.08±2.02min. The information content was excellent only in 17 (10.9%) of all videos while for a majority of them it was poor (57.4% n=89). Fair videos constituted 31.7% (n=49) of the videos. There was no relation between the trustworthiness of the videos’ contents and either their viewings or ratings (p=0.561, p=0.0966, respectively). Videos uploaded by health professionals were more reliable than those uploaded by laypersons (p<0.001).

ConclusionsThe study suggests that although some videos, especially those uploaded by healthcare professionals, are useful; the majority of them have misleading information. Therefore, they are not a reliable source of PE information for patients. It is incumbent on urologists to counsel patients for other available useful internet information sources on PE.

Evaluar la calidad de la información de los vídeos de YouTube relacionados con la eyaculación precoz (EP).

Materiales y métodosSe realizó una búsqueda en YouTube sobre EP en agosto de 2018. Dos urólogos con experiencia vieron y clasificaron cada vídeo por sus fuentes, sugerencias y contenido científico (excelente, aceptable o deficiente).

ResultadosDe los 300 vídeos vistos en YouTube, se incluyeron y analizaron 155 vídeos. La duración media del vídeo (media±desviación estándar) fue de 3,08±2,02min. El contenido científico fue excelente solo en 17 (10,9%) de todos los vídeos, mientras que en la mayoría de ellos esta fue deficiente (57,4%; n=89). Los vídeos aceptables constituyeron el 31,7% (n=49). No hubo relación entre la fiabilidad de los contenidos de los vídeos y el número de visualizaciones o las valoraciones de los usuarios (p=0,561; p=0,0966, respectivamente). Los vídeos subidos por profesionales sanitarios fueron más fiables que los subidos por profanos (p<0,001).

ConclusionesEl estudio sugiere que, aunque algunos vídeos, especialmente aquellos publicados por profesionales sanitarios, son útiles, la mayoría de ellos contienen información engañosa. Por tanto, no son una fuente fiable de información sobre la EP para los pacientes. Les corresponde a los urólogos aconsejar a los pacientes sobre otras fuentes de información disponibles en Internet que resulten útiles.

Premature ejaculation (PE) is a common male sexual dysfunction with a prevalence varying from 19.8% to 55%.1,2 Men with PE report a low degree of satisfaction with their sexual relationship, low satisfaction in sexual intercourse, difficulty relaxing during intercourse, and less frequent intercourse.3,4 However, the negative effect of PE extends beyond sexual dysfunction. PE can negatively affect self-confidence as well as the relationship with the partner, and can result in mental distress, anxiety, embarrassment and depression.5 However, a recent report indicated that only 9% of men with self-reported PE discussed their condition with a physician.6 Embarrassment and believing that there is no effective treatment are the major reasons for not seeking advice on PE with their doctor.7,8

More and more, sites with video content are considered to be valid sources of information. You Tube, the most popular of these sites, has more than 2 billion views each day, with a new video uploaded on average every minute and the typical user spending at least 15min each day on the site.9,10 Recent reports have shown a significant increase in the use of the internet for obtaining health information.11,12 However, healthcare providers and government agencies are concerned about the accuracy and quality of the information given on the internet, for two main reasons: the increased use of You Tube to present subjective information and, more importantly, a lack of guidelines and monitoring of the content of the information on the site. These issues raise questions of the reliability of this information and the risk of propagating misleading information.13–16

Use of You Tube as a source of information has not yet been evaluated. In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the quality of information in You Tube videos pertaining to premature ejaculation.

Material and methodsYou Tube (http://www.youtube.com) was searched using the key word “premature ejaculation” on August 28, 2018 by two senior urologists. The first 300 videos were screened on the assumption that the majority of users would not go beyond the first 10–15 pages for a searched item.

The videos were analyzed if they were in English, <10min in length, and had primary content related to premature ejaculation. We did not analyze patient testimonials, videos without sound, not related to premature ejaculation, unable to access, news reports about an individual's premature ejaculation diagnosis or treatment, satire, duplicated, film scene and song name. We extracted the title and duration of the video, number of views, viewer rating, author of the video, affiliation of the author (layperson or medical professional) and suggestions of the video (no suggestion, drug treatments, surgical treatments, behavior treatments and alternative treatments).

Two urologists analyzed each video's overall information and scientific content and rated it as excellent, fair or poor as a co-decision. Due to lack of standardized and validated means available to perform this kind of analysis, a set of predetermined criteria were used to grade the videos. An excellent video required accurate facts and discussion of both advantages and disadvantages of a given video's suggestion. A fair rating would also be factually correct, but only discuss advantages of a suggestion. A poor video would neither be factually correct nor discussing any particular facets of premature ejaculation.

Continuous variables were given as mean±standard deviation while categorical ones were given as number and percentage (%). The normality was tested with Shapiro–Wilk Test. Mann–Whitney U Test was used for comparison of groups of two. For comparison of three or more groups, Kruskal–Wallis H Test was used. Pearson Chi-Square and Fisher's Exact Test were used to analyze the crosstabs. Statistical analysis was done with IBM SPSS for Windows version 21.0 package (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). The level of significance used was p<0.05.

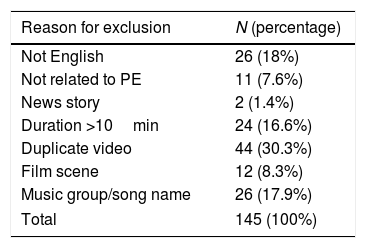

ResultsAmong the 22,700 videos, we analyzed the first 300 videos. Of the 300 videos, 155 (51.7%) videos were included in the study while 145 (48.3%) were excluded according to our study criteria. The reasons for the exclusions are listed in Table 1 in detail.

Mean video length (mean±standard deviation) was 3.08±2.02min, mean date duration was 910.52±650.60 days, mean rating was 104.81±341.54, and mean view was 53,178.45±145,896.57 and mean view/date duration was 48.44±115.43view/day.

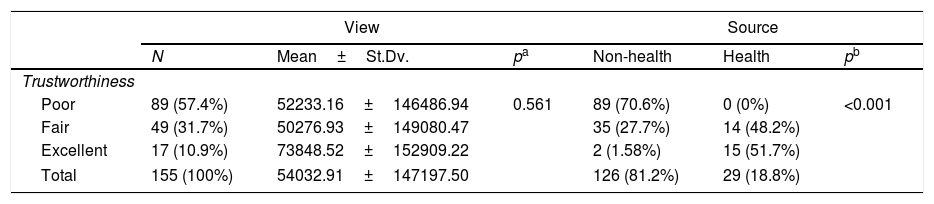

Our ratings for videos showed that the information content was excellent only in 17 (10.9%) of all videos while a majority of them were poor (57.4% n=89). Fair videos constituted 31.7% (n=49) of the videos.

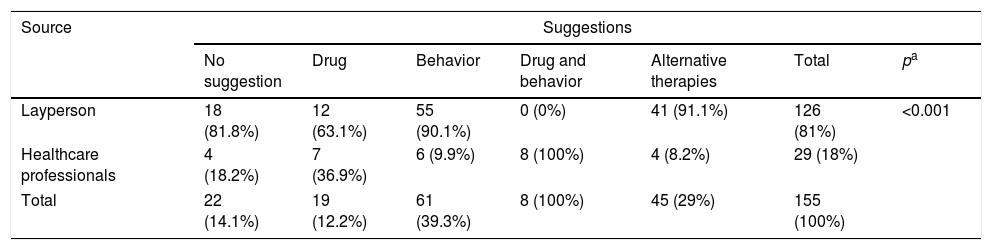

Kruskal–Wallis test revealed that there was no relation between the trustworthiness of the videos’ contents and neither their viewings nor ratings (p=0.561, p=0.0966, respectively) (Table 2). According to the analysis of videos rated by us, videos uploaded by health professionals were more reliable than those uploaded by laypersons (p<0.001). Detailed characteristics of the videos related to the sources are presented in Table 3.

The relationship between physician rated content and view/source of the You Tube videos.

| View | Source | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean±St.Dv. | pa | Non-health | Health | pb | |

| Trustworthiness | ||||||

| Poor | 89 (57.4%) | 52233.16±146486.94 | 0.561 | 89 (70.6%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Fair | 49 (31.7%) | 50276.93±149080.47 | 35 (27.7%) | 14 (48.2%) | ||

| Excellent | 17 (10.9%) | 73848.52±152909.22 | 2 (1.58%) | 15 (51.7%) | ||

| Total | 155 (100%) | 54032.91±147197.50 | 126 (81.2%) | 29 (18.8%) | ||

Suggestions of the videos according to their sources.

| Source | Suggestions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No suggestion | Drug | Behavior | Drug and behavior | Alternative therapies | Total | pa | |

| Layperson | 18 (81.8%) | 12 (63.1%) | 55 (90.1%) | 0 (0%) | 41 (91.1%) | 126 (81%) | <0.001 |

| Healthcare professionals | 4 (18.2%) | 7 (36.9%) | 6 (9.9%) | 8 (100%) | 4 (8.2%) | 29 (18%) | |

| Total | 22 (14.1%) | 19 (12.2%) | 61 (39.3%) | 8 (100%) | 45 (29%) | 155 (100%) | |

Patients with premature ejaculation (PE) are reluctant to discuss their sexual problems with their family, friends and also doctors. In an effort to seek healthcare decisions, patients with PE are increasingly turning to the internet to better understand their sexual disorders and treatments. Our study suggests that You Tube hosts many videos related to PE and health consumers are viewing this information.

Misleading information is found on You Tube and healthcare consumers can encounter such material during the information- seeking process. Singh et al., studying videos related to rheumatoid arthritis, reported that 54.9% (n=102) of the videos were useful and 30.4% were misleading, including misinformation about the causal mechanism and the promotion of unscientific therapies that are yet to be approved by an appropriate agency.17 A recent study on prostate cancer information found that among the reviewed videos, 73% had fair or poor information content.18 Similar to these reports mentioned above, the present study found that the majority of the videos pertaining to PE on You Tube had poor quality information. Videos with poor quality information may influence negatively healthcare consumers with PE and can have catastrophic implications.

As far as the relationship between the trustworthiness of the videos and both their ratings and viewership are concerned, the literature has found different results. Akshay et al. reported that useful videos were rated and viewed significantly higher than misleading videos.19 A recent study found that no significant correlation existed between the content and the number of views or rating by You Tube viewers.18 Our analysis indicates that there is no significant correlation between the content and the number of views or rating.

Reviewing the excellent videos with regard to their source, we obviously see that the majority of the excellent or fair videos have been uploaded by healthcare professionals. This situation was also reported in videos on incontinence, with Sajadi and Goldman finding that 46% of videos presented useful information. Of this useful information, 64% came from healthcare professionals or organizations.20 Clerici et al. analyzed videos on rhabdomyosarcoma. They found that 82.5% (n=149) of the videos involved personal experience, and only 16.7% of all the videos included useful information. Only one created by a physician was completely accurate.21 Similar to these results, in a study on videos related to rheumatoid arthritis conducted by Singh et al., 36.4% of the videos were from independent users, followed by profit organizations (22.5%), government entities/schools and professional organizations (21.5%), and health information websites (19.6%). Strikingly, 73.9% of the videos from medical advertisements and for-profit organizations were misleading.17

This study suggests that the majority of the videos pertaining to PE on You Tube contain misleading information. Notably, these videos were uploaded by laypersons. There were no differences in the number of views and their ratings between excellent and poor videos. Therefore, these findings suggest that there is a high probability for lay users to encounter misleading information. In view of these findings, urologists should take responsibility for counseling their patients on accessing the internet to receive aid in their decision-making. Moreover, authoritative videos by trusted sources should be posted for dissemination of reliable dissemination.

ConclusionIn conclusion, although some videos, especially those uploaded by healthcare professionals, are useful, the majority of them have misleading information. Therefore, You Tube is an inadequate source of information for individual persons seeking to better receive information on PE. It is incumbent on urologists to counsel patients with other available useful internet information sources on PE.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestThere was no conflict of interest.