We aimed to investigate the effect of major thoracic surgery on sexual functions and psychogenic aspects of men who underwent surgery for lung cancer.

Material and methodsThis study was conducted to assess depression and erectile function in patients who underwent surgical treatment for lung cancer. The data of 50 patients in the study group, and 39 participants in the control group who met the criteria were analyzed. Erectile dysfunction (ED) and symptoms of depression were assessed in patients before and three months after surgery.

ResultsThe mean ages were 58.4±11.6 and 61.3±6.9 years; the mean BMIs were 25.6±4.3kg/m2 and 24.8±5.7kg/m2; the mean forced vital capacities (FVC) were 3.1±0.6L and 3.4±1.4L; the mean FEV1/FVC were 86.1±10.3 and 80.3±4.1; the mean Beck Depression Inventory scores were 9.3±6.9 and 6.0±6.2, and the mean FVC% were 82.9±14.9 and 82.0±26.2 for the study and control groups, respectively. The mean preoperative International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) scores were 14.1±4.1 and 10.8±4.7 postoperative in the study group, and 17.4±8.6 in the control group. The logistic regression analysis showed that postoperative complications resulted in a 3.95-times higher risk of suffering from ED.

ConclusionOur study supported that surgical treatment of lung cancer adversely affected psychogenic status and sexual function due to its stringent nature. The fear of death affects the quality of life and the psychogenic aspect of the patients with lung cancer. Clinicians should thoroughly inform the patients about sexual dysfunction and psychogenic disorders, and when needed providing an appropriate sexual counseling and treatment is necessary. Good communication contributes to a better quality of life.

Nos proponemos investigar el efecto que tiene la cirugía torácica mayor en las funciones sexuales y los aspectos psicogénicos de los varones que se sometieron a una intervención quirúrgica para tratar el cáncer de pulmón.

Material y métodosEste estudio se realizó con el fin de valorar la depresión y la función eréctil en los pacientes que se sometieron a una intervención quirúrgica para tratar el cáncer de pulmón. Se analizaron los datos de 50 pacientes en el grupo de estudio y 39 participantes del grupo control que cumplieron con los criterios. Se evaluó la disfunción eréctil (DE) y los síntomas de depresión en los pacientes antes de la intervención y 3 meses después de la misma.

ResultadosLa media de edades fue de 58,4±11,6 años y 61,3±6,9 años; la media del IMC fue de 25,6±4,3kg/m2 y 24,8±5,7kg/m2; la media de las capacidades vitales forzadas (CVF) fue de 3,1±0,6l y 3,4±1,4l; la media de los VEF1/FCV fue de 86,1±10,3 y 80,3±4,1; la media de los resultados del inventario de depresión de Beck fue de 9,3±6,9 y 6,0±6,2, y la media de los porcentajes de CVF fue de 82,9±14,9 y 82,0±26,2 para el grupo de estudio y el de control, respectivamente. Las puntuaciones medias preoperatorias en el Índice Internacional de Función Eréctil (IIFE-5) fueron de 14,1±4,1 y 10,8±4,7 en las postoperatorias en el grupo de estudio, y 17,4±8,6 en el grupo de control. El análisis de regresión logística mostró que las complicaciones del postoperatorio resultaron en un riesgo 3,95 veces mayor de sufrir DE.

ConclusionesNuestro estudio apoya que, dada la severidad del tratamiento quirúrgico del cáncer de pulmón, los pacientes vieron afectado su estado psicogénico y su función sexual. El miedo a la muerte afecta la calidad de vida y el aspecto psicogénico de los pacientes con cáncer de pulmón. El personal médico debería informar detenidamente a los pacientes acerca de la disfunción sexual y los trastornos psicogénicos y, siempre que sea necesario, deberán proporcionar asesoramiento sexual y tratamiento. Una buena comunicación contribuye a una mejor calidad de vida.

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is the most common form of sexual dysfunction that can cause ongoing emotional distress and disrupt sexual relationships.1 Several factors can affect sexual function including cancer treatment, chronic diseases, and major surgeries. Previous studies have investigated the relationship between major surgery as in cardiac surgery and sexual dysfunction.2,3 The possibility of the sexual function being affected after cancer treatment, due to physical and psychological etiologies, ranges from 40% to 100%.4 The prevalence of psychological problems in patients with lung cancer was reported between 35.1% and 43.6%.5 ED is defined as a persistent inability to attain and maintain an erection sufficient enough to permit satisfactory sexual performance.6 In a collaborative study of eight European centers, ED prevalence was found 30% of the male population aged 40–79 with a mean age of 60 years.7 There are several risk factors in the etiology of ED, such as aging, smoking, drug use, diabetes mellitus, and vascular disease.8 Higher prevalence of ED has been reported in men who smoke ≥ 20 packs/year compared to 10–19 packs/year smokers.9

Sexual problems may develop at any point during the course of a patient's cancer, including at diagnosis, during treatment, or during post-treatment follow up.10 Such problems typically continue after cancer treatment and do not resolve for a while. To date, many studies have been reported on sexual function in patients with different types of cancer, questioning sexual function.11,12 To the best of our knowledge, there is no any clinical research specifically investigated the relationship between thoracotomy and sexual functioning in patients who underwent major thoracic surgery for lung cancer. Our objective was to show the effects of major thoracic surgery on sexual function and psychological status in men with lung cancer.

Material and methodsStudy design and patient populationTo the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first in the literature to compare ED, psychogenetic, and pulmonary functions in patients underwent thoracotomy for lung cancer. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and complied with local regulatory requirements. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ondokuz Mayis University.

Fifty patients in the study group and 39 healthy participants in the control group completed the study. Fourteen of them were out of follow-up, and the study was completed with 50 patients. All patients were orally and written informed about the study and consent forms were obtained. This was a descriptive and cross-sectional study, conducted to assess depression and erectile function in 50 male patients who underwent thoracotomy or video thoracoscopic surgery for lung cancer. All subjects in the study and control groups were married men who were monogamous and having regular sexual relations before surgery. Before the surgery and after the postoperative third month, all patients were asked to fill out the International Index of Erectile Function Questionnaire (IIEF-5) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) in addition to pulmonary function.

Main outcome measuresAssessment of erectile functionAfter providing personal medical histories, including any history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, drug use, liver or kidney diseases, and information on previous operations and sexual history, the patients were asked to complete the validated Turkish form of the IIEF-5 which is an excellent diagnostic tool with high sensitivity and specificity (sensitivity=0.97; specificity=0.88).13 The IIEF-5 questionnaire consists of six questions each scored on a scale of 1 (almost never or never) to 5 (almost always or always). If a total score of six questions is equal to or greater than 25, the erectile function is considered normal. However, any score below 25 indicates the presence of ED. Subsequently, men were classified into five diagnostic categories: no ED (Erectile Function (EF) score=26–30); mild ED (EF score=22–25); mild to moderate ED (EF score=17–21); moderate ED (EF score=11–16); and severe ED (EF score=6–10).14

Assessment of depressive symptomsThe Beck's depression inventory, first described in 1961, is one of the most commonly used tools for the self-measure of emotional, cognitive, somatic, and motivational components.15

Preoperative and postoperative psychological statuses of the patients in this study were assessed as no depression (<13 pts), minimal–moderate depressive symptoms (range 14–19), moderate–severe depressive symptoms (range 20–29), and severe depressive symptoms (range 30–63). A score of less than 14 was considered of no depression. Because the participants who were allocated to the control group were consisted from healthy volunteers, BDI assessment performed only once.

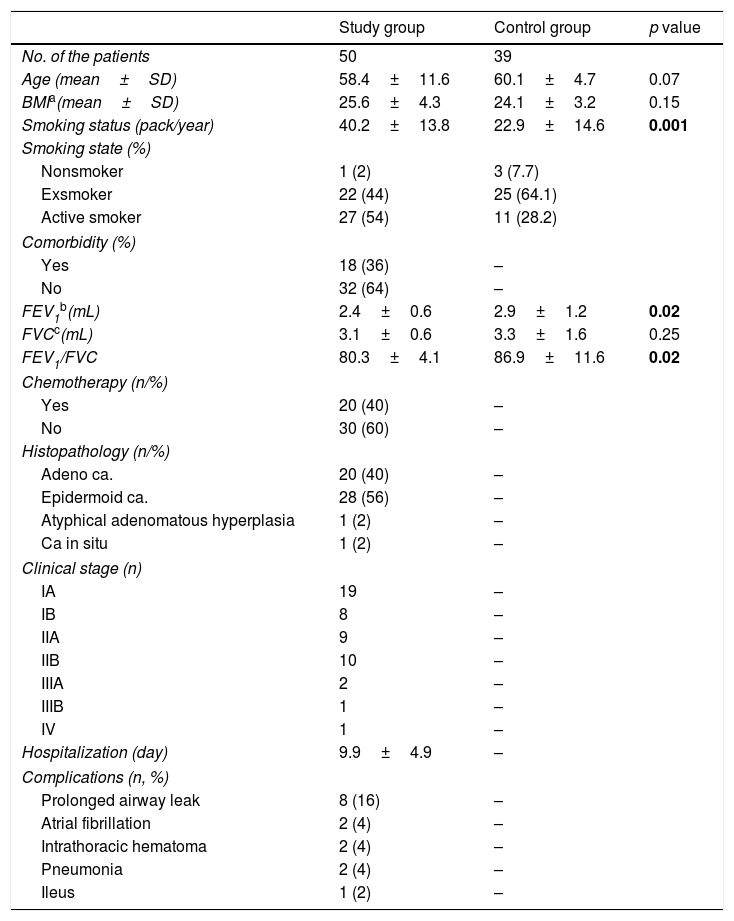

Secondary outcomesSmoking state and status (packs/year), surgical intervention, hospitalization time, and postoperative complications were recorded. Histopathological evaluation and clinical stages of the patients were performed (Table 1). The patients’ smoking histories were evaluated as packs per year (pack/year). Spirometry was performed to evaluate respiratory functions.

Characteristics of the study and control group.

| Study group | Control group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of the patients | 50 | 39 | |

| Age (mean±SD) | 58.4±11.6 | 60.1±4.7 | 0.07 |

| BMIa(mean±SD) | 25.6±4.3 | 24.1±3.2 | 0.15 |

| Smoking status (pack/year) | 40.2±13.8 | 22.9±14.6 | 0.001 |

| Smoking state (%) | |||

| Nonsmoker | 1 (2) | 3 (7.7) | |

| Exsmoker | 22 (44) | 25 (64.1) | |

| Active smoker | 27 (54) | 11 (28.2) | |

| Comorbidity (%) | |||

| Yes | 18 (36) | – | |

| No | 32 (64) | – | |

| FEV1b(mL) | 2.4±0.6 | 2.9±1.2 | 0.02 |

| FVCc(mL) | 3.1±0.6 | 3.3±1.6 | 0.25 |

| FEV1/FVC | 80.3±4.1 | 86.9±11.6 | 0.02 |

| Chemotherapy (n/%) | |||

| Yes | 20 (40) | – | |

| No | 30 (60) | – | |

| Histopathology (n/%) | |||

| Adeno ca. | 20 (40) | – | |

| Epidermoid ca. | 28 (56) | – | |

| Atyphical adenomatous hyperplasia | 1 (2) | – | |

| Ca in situ | 1 (2) | – | |

| Clinical stage (n) | |||

| IA | 19 | – | |

| IB | 8 | – | |

| IIA | 9 | – | |

| IIB | 10 | – | |

| IIIA | 2 | – | |

| IIIB | 1 | – | |

| IV | 1 | – | |

| Hospitalization (day) | 9.9±4.9 | – | |

| Complications (n, %) | |||

| Prolonged airway leak | 8 (16) | – | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 (4) | – | |

| Intrathoracic hematoma | 2 (4) | – | |

| Pneumonia | 2 (4) | – | |

| Ileus | 1 (2) | – | |

Sexually active adult male patients having regular sexual activity who underwent thoracotomy for lung cancer with no history of bleeding disorders and previous interventions including major surgery, radiotherapy, hormonal or psychiatric therapy (psychiatric diseases and antidepressant medications most depress erectile function) that may affect genital system were included into the study group. Patients younger than 18 years were also excluded.

Sexual active healthy males who were willing to participate to study with no history of abovementioned interventions were included in the control group.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 15.0 for Windows) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) and frequency (%). A comparison of preoperative and postoperative IIEF-5 scores, and Beck Depression Inventory scores were performed using a Student's t-test (two-way). To compare the groups, we used the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normal data. Results were evaluated using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test to compare between groups. The intra-group data within each of the three groups were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-normal data. Pearson's Chi-Square and Fisher's exact tests were used to compare percentages. A level of p<0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsThe mean ages of the study group and control group were 58.4±11.6 (29–77) and 60.1±4.7 (48–78) years, respectively (p=0.07). The mean body mass indexes (BMIs) were 25.6±4.3 and 24.1±3.2kg/m2 (p=0.15), respectively. Smoking status were 40.2±13.8 (0–100) packs/year in the study group and 22.9±14.6 (0–40) packs/year in the control group (p=0.001). In the study group, one patient (2%) was a nonsmoker, 22 (44%) were ex-smokers, and 27 (54%) were active smokers. In the control group, three men (7.7%) were nonsmoker, 25 (64.1%) were ex-smokers, and 11 (28.2%) were active smokers. Of the patients in the study group, 18 (36%) had comorbidities such as cardiovascular, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus.

The mean forced vital capacities (FVCs) were 3.1±0.6L for the study group and 3.3±1.6L (p=0.25) for the control group. The mean FVC% were 82.9±14.9 for the study group and 81.2±24.4 (p=0.79) for the control group. The mean forced expiratory volume in 1st second (FEV1)/FVC was 80.3±4.1 for the study group and 86.9±11.6 (p=0.02) for the control group. In the study group, 20 (40%) patients received chemotherapy following surgery, whereas 30 (60%) did not.

Histopathological examination of the study group revealed adenocarcinoma in 20 patients (40%), epidermoid carcinoma in 28 (56%) and in situ carcinoma in 2 (4%). The mean hospital stay in the study group was 9.9±4.9 (3–26) days. TNM classification for non-small cell lung cancer in the study group is shown in Table 1. Among the patients, 8 (16%) had prolonged postoperative airway leakage, 2 (4%) had atrial fibrillation, 2 (4%) had intrathoracic hematoma, and 1 (2%) had paralytic ileus.

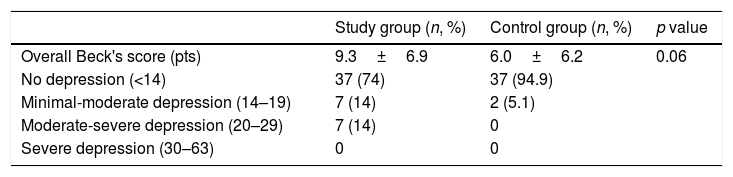

The mean BDI scores were 9.3±6.9 and 5.7±6.4 in the study and control groups, respectively (p=0.05) (Table 2). Among the subjects in the study group, seven patients (14%) had minimal–moderate depressive symptoms and 7 (14%) had moderate–severe depressive symptoms, whereas only two patients (5.1%) in the control group showed depression. The mean postoperative Beck's score was 9.3±6.9 and it was found to be associated with ED during study period (p=0.01).

Beck's scores of the groups.

| Study group (n, %) | Control group (n, %) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Beck's score (pts) | 9.3±6.9 | 6.0±6.2 | 0.06 |

| No depression (<14) | 37 (74) | 37 (94.9) | |

| Minimal-moderate depression (14–19) | 7 (14) | 2 (5.1) | |

| Moderate-severe depression (20–29) | 7 (14) | 0 | |

| Severe depression (30–63) | 0 | 0 |

p<0.05: significant.

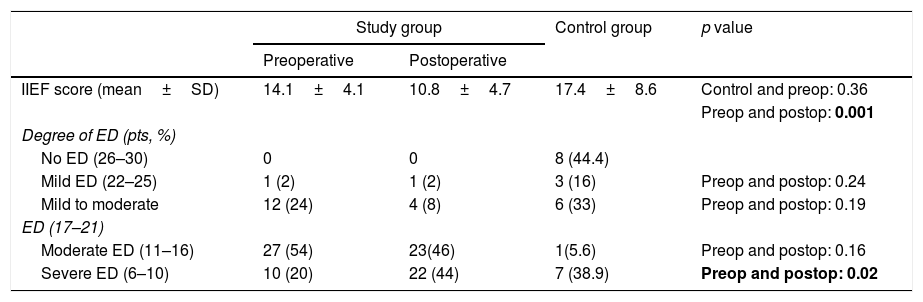

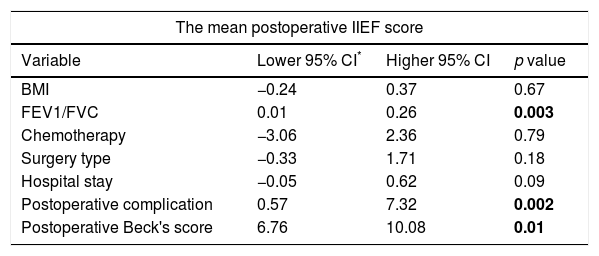

The mean preoperative IIEF-5 scores for the study group was 14.1±4.1 (4–22), and the mean postoperative IIEF-5 score was 10.8±4.7 (1–22) (p<0.001). The mean IIEF-5 score for the control group was 17.4±8.6. The mean postoperative IIEF-5 value significantly decreased when compared to the preoperative value in the study group (p=0.001) (Table 3). The IIEF scores were similar in the control group and the study group in the preoperative term (p=0.36). Logistic regression analysis showed that a decrease in FEV1/FVC was associated with increased of ED (p=0.02), with a confident interval (CI) of 0.01–0.26; logistic regression analysis also showed that the presence of postoperative complications resulted in 3.95-fold higher risk of ED (p=0.02, CI=0.57–7.32). There was no increased risk of ED in terms of BMI, chemotherapy, and hospital stay (p>0.05) (Table 4).

IIEF scores and correlations between the groups.

| Study group | Control group | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | Postoperative | |||

| IIEF score (mean±SD) | 14.1±4.1 | 10.8±4.7 | 17.4±8.6 | Control and preop: 0.36 |

| Preop and postop: 0.001 | ||||

| Degree of ED (pts, %) | ||||

| No ED (26–30) | 0 | 0 | 8 (44.4) | |

| Mild ED (22–25) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 3 (16) | Preop and postop: 0.24 |

| Mild to moderate | 12 (24) | 4 (8) | 6 (33) | Preop and postop: 0.19 |

| ED (17–21) | ||||

| Moderate ED (11–16) | 27 (54) | 23(46) | 1(5.6) | Preop and postop: 0.16 |

| Severe ED (6–10) | 10 (20) | 22 (44) | 7 (38.9) | Preop and postop: 0.02 |

p<0.05: significant.

Relationships between mean postoperative IIEF-5 score and other variables using logistic regression analysis.

| The mean postoperative IIEF score | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Lower 95% CI* | Higher 95% CI | p value |

| BMI | −0.24 | 0.37 | 0.67 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.003 |

| Chemotherapy | −3.06 | 2.36 | 0.79 |

| Surgery type | −0.33 | 1.71 | 0.18 |

| Hospital stay | −0.05 | 0.62 | 0.09 |

| Postoperative complication | 0.57 | 7.32 | 0.002 |

| Postoperative Beck's score | 6.76 | 10.08 | 0.01 |

CI* confidential index, p<0.05: significant.

Our main aim was to investigate the relationship between thoracotomy, psychological status and possible alterations in erectile function in men with lung cancer. Cancer is a chronic disease that generally results in death when early diagnosis and early treatment are not properly done. Lung cancer accounts for around 13% of all types of cancer and the most frequently seen and lethal type of all cancers.16 Eighty percent of lung cancers have been reported as non-small cell carcinoma (NSCLC). In our study, 96% of the patients were in NSCLC group. This discrepancy can be explained by the small number of our patients.

Due to vascular, hormonal, and anatomical reasons, major pelvic surgeries can cause sexual dysfunction.17 Although sexual dysfunction is not a life-threatening condition, it may affect a man's sense of well-being and social status due to several reasons such as patient reluctance to discuss the topic, lack of assessment training, or a lack of standardized sexuality questionnaires,18 we observed no patient reluctance to discuss sexuality and thus believe validated IIEF-5 questionnaire could easily be used with cancer patients.

Our results showed that postoperative long-term complications (p=0.02) and FEV1/FVC (p=0.02) were associated with ED. Chronic airway obstruction may lead to chronic hypoxemia. In addition to major surgical procedures, chronic hypoxia may cause deterioration of the delicate balance between the four previously mentioned factors and can predispose to the development of ED.19 Molecular oxygen and testosterone have an important role in the release of nitric oxide. Thus, hypoxia decreases nitric oxide synthase activity.20 The standard cut-off ratio for airway obstruction of FEV1/FVC is accepted as 0.7, with any ratio lower than 0.7 suggesting an airway obstruction.21 Although the mean FEV1/FVC significantly decreased in the study group (80.3±4.1) compared to the control group (86.1±10.3), ED cannot be explained by hypoxia, because the mean value of FEV1/FVC was greater than 0.7 in both groups. Although sexual dysfunction could not be attributed to respiratory changes for this study, smoking may contribute to further development of erectile dysfunction mainly because most of the patients were smokers, and smoking increases the effects of other vascular disorders, including high blood pressure and atherosclerosis.22 In our study, thoracic surgery led to a marked postoperative increase of severe ED as shown Table 3, but there was no significant change in patients with mild and mild to moderate ED in the study group. The decrease in the postoperative IIEF-5 score, and similarity of the mean IIEF-5 scores both in the study and control groups within the 3-month period suggested that the mean ED score decreased secondary to thoracotomy. It has been shown that chronic diseases such as metabolic disorders or cancer cause deterioration in mental well-being.23 In this context, the increased number of patients with severe ED can be explained by the additive effects of thoracic surgery, underlying complications, psychological impairment24 and endothelial dysfunction. Depression prevalence was found between 37 and 46% in curatively resected lung cancer patients.25 In concordance with literature, our results showed that 17 patients (34%) had mild and moderate depressive symptoms. We showed postoperative complications were associated with an increase in severe ED and depressive symptoms. Tumors located in the abdomen and pelvis may cause erectile dysfunction by affecting the vascular and autonomic plexus involved in erectile function. A new cancer diagnosis can lead to different degrees of depression in patients with distantly located tumors far from the genital or abdominal region and can lead to ED. Because significant number of our patients were diagnosed with early-stage lung cancer (Stage I and Stage II), we believe that the latter mechanism might have been effective on ED (Table 3.)

In addition, we showed a statistically significant association between postoperative IIEF-5 scores and BDI scores. Far location of the surgical field away from the genital region, led us to think that psychological reasons were the main reason for ED in patients with lung cancer. Although the majority of the patients were within non-depressive limits, the moderate depressive symptom rate in the study group was significantly higher than the control group. The negative impact of depression on sexual functioning has been commonly described among women, but less frequently in men in the literature. Fabre et al., reported a correlation with severity of depressive symptoms and decreased orgasm and erection.26 Recovery of BDI score in the post-operative term suggested us that erectile dysfunction might have been affected by depressive state.

Sex hormone level was statistically non-significantly reported to tend decline in lung cancer.27 Therefore, a different mechanism may play role in erectile dysfunction. Early side effects of chemotherapy mostly appear seven-to-ten days after administration and may affect the energy and desire of the patients, but this does not last long. Late complications usually occur after three months. When compared with non-chemotherapy arm, our finding showed no association with ED and chemotherapy. This can be explained with a single measurement of the sexual function directly after chemotherapy may not be indicative of long-term outcomes, and longer follow-up periods are needed to support this hypothesis.

Serious complications require additional intervention may have resulted in longer hospitalization. However, in the present study, the mean hospital stay was rather shorter because of the low incidence of complications. Therefore, we think the duration of hospital stay did not affect ED, but the presence of complications that prolong hospitalization may affect ED.

The limitations of this study include a failure to compare preoperative and postoperative plasma testosterone levels, the small number of patients, the fact that the patients’ partners were not queried on female sexual function, and the lack of investigation of other causes of sexual dysfunctions such as ejaculatory disorders, orgasmic function, and sexual desire. Further detailed longitudinal studies are needed to study these variables in the future.

ConclusionThis study supports that surgical treatment of lung cancer has multiple and variable adverse effects on the psychogenic status and sexual function. The stringent treatment processes that are applied may exacerbate ED. Moreover, underestimation of ED by physicians and the fear of death in patients may lower the quality of life in cancer patients. Before the thoracotomy, all patients with lung cancer should be informed in detail about sexual dysfunction and psychogenic disorders. The clinician's responsibility is to provide patients with appropriate sexual counseling and rehabilitation. Good communication contributes to a better quality of life. Since the erectile function on a psychosocial basis has been poorly studied to date, the present study will contribute an important addition to the literature.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Authors’ contributionMustafa Suat Bolat, Burcin Celik, Hale Kefeli Celik, and Ekrem Akdeniz participated in the conception and performance, data acquisition, and analysis and data of the work that has resulted in the submitted manuscript.

Mustafa Suat Bolat, Burcin Celik, Hale Kefeli Celik participated in the drafting of the article and in its possible revisions.

Mustafa Suat Bolat, Burcin Celik, Hale Kefeli Celik, and Ekrem Akdeniz approved the final version to be published.

FundingNone declared.

Conflict of interestAuthors declare no conflict of interest