The links between body weight and sexuality, notably sexual dysfunction (SD), are intricate and not yet fully understood. A more individual-focused evaluation of sexual difficulties, as recently provided by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), contributes to improve precision in SD diagnosis and has the potential to advance our knowledge on the association between body weight and SD.

ObjectivesTo identify gender differences in sexual behaviors and SD among Portuguese men and women within different classes of body mass index (BMI); and to explore the association between BMI and SD by using the new DSM-5 criteria.

Material and methodsFace-to-face interviews followed by self-completed questionnaires of primary healthcare users in Portugal (n=323). Data on sociodemographic variables, BMI, sexual behaviors and SD were collected. DSM-5 criteria were used to assess sexual dysfunction. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) and the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) for men and women, respectively, were used for comparison purposes.

ResultsOverweight and obese women reported less sexual partners, less satisfaction with sexual frequency and rated sexual life as less important. These differences were not found among men. Normal weight men and women had a higher score of IIEF and FSFI, respectively, than those overweight and obese. No significant effects of BMI scale on SD following DMS-5 were detected.

ConclusionsWomen's sexual function is more impacted by BMI than men's. Individual-orientated approaches, as proposed in DSM-5, may allow a better understanding on the relation between body size and sexuality in both genders.

La relación entre el peso corporal y la sexualidad, en particular la disfunción sexual (DS), es compleja y aún no se entiende por completo. Una evaluación de las dificultades sexuales más centrada en el individuo, como la recientemente proporcionada por el Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales (DSM-5), contribuye a mejorar la precisión en el diagnóstico de la DS y tiene el potencial para avanzar en el conocimiento sobre la asociación entre el peso corporal y la DS.

ObjetivoIdentificar diferencias de género en conductas sexuales y DS entre varones y mujeres portuguesas con diferentes clases de índice de masa corporal (IMC), y explorar la asociación entre IMC y DS utilizando los nuevos criterios del DSM-5.

Material y métodosEntrevistas cara a cara con usuarios de atención primaria de salud en Portugal (n=323), seguidas de cuestionarios autocompletados. Se recogieron datos sobre variables sociodemográficas, IMC, conductas sexuales y DS. Los criterios del DSM-5 se utilizaron para evaluar la DS. El Índice Internacional de Función Eréctil (IIEF) y el Índice de Función Sexual Femenina (IFSF) se utilizaron con fines comparativos, para varones y mujeres, respectivamente.

ResultadosLas mujeres con sobrepeso y obesidad comunicaron menos parejas sexuales, menor satisfacción con la frecuencia sexual y calificaron la vida sexual como menos importante. Estas diferencias no se encontraron entre los varones. Los varones y mujeres de peso normal tuvieron una puntuación más alta de IIEF y IFSF, respectivamente, que los varones y las mujeres con sobrepeso y obesidad. No se detectaron efectos importantes de la escala del IMC en la DS según el DSM-5.

ConclusiónLa función sexual de las mujeres está más afectada por el IMC que la de los varones. Los enfoques orientados al individuo, como se propone en el DSM-5, pueden permitir una mejor comprensión de la relación entre el peso corporal y la sexualidad en ambos sexos.

Obesity is a worldwide epidemic that has registered a dramatic increase over the last decades. By 2025, its global prevalence is expected to rise up to 18% in men and 21% in women.1 While associated with increased all-cause mortality,2 obesity is also a risk factor for various noncommunicable diseases,3 such as cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes.4 Moreover, stigma and discrimination toward overweight and obese individuals, self-perception of body size and shape, and the way it influences their social networks pose negative consequences for individuals’ physical and psychological health, as well as for their psychosocial functioning.5 Notwithstanding, the intricate association between obesity and sexuality, among other aspects of quality of life, is not yet fully understood.6,7

Previous studies on this relation have produced conflicting results.8,9 For example, overweight and obese subjects are more likely to have fewer sexual partners for a delimited time frame when compared with normal weight individuals.10 In addition, they are more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors, such as multiple and/or casual risky partners and unprotected sexual intercourse, than normal weight individuals.10,11 On the contrary, no differences in sexual practices (e.g., masturbation, oral sex, intercourse)12 and unintended pregnancies8 were found between sexually active women of different body sizes measured as body mass index (BMI).

The exploration of body size and its relationship with sexuality has been mainly studied in narrowly diverse samples, such as college students9 and low income women.11 Considering that this relation may be directly or indirectly influenced by socioeconomic, psychological and demographic variables,9 the generalizability of the results depends on the analysis of more diverse samples. Since previous studies have reported differences between men and women in the way sexuality is influenced by body weight, gender seems to be a key variable to consider in such investigations.10,13 For instance, the analysis of a national random sample of French individuals revealed that sexual dysfunction (SD), the impairment of sexual functioning caused by clinical syndromes,14 was associated with BMI in men but not in women.10 In fact, whereas higher prevalence of SD has been consistently reported in overweight and obese men, and not in their lean counterparts,15,16 this association is not as clear for women.10,17

According to the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), a positive diagnosis of SD occurs when individuals experience difficulties during 75–100% of the sexual encounters for a minimum period of six months, and these problems have caused them serious clinical distress.14,18 These new morbidity criteria provide more precise thresholds with regard to the frequency (all the time versus specific situations/partners), duration (onset of the difficulty at the first sexual experience versus after a period of normal sexual function) and severity (from mild to severe distress over the symptoms) of sexual difficulties.14 Therefore, the diagnostic classification of DSM-5 withdraws the strict medical model, acknowledging a linear sexual response cycle for both genders, and emphasizes the individual evaluation of sexual difficulties, considering it separately for men and women.18 The use of DSM-5 criteria results in lower prevalence estimates than those of population studies following less strict severity criteria.19 However, the contribution of the new DSM-5 criteria to our understanding on the relation between sexuality and other variables, such as body weight and self-perception of body shape, is currently unknown.

The main aim of this study is to contribute to overcome the gaps in the current knowledge on the association between body size and sexuality. To accomplish this, it addresses the following specific objectives: (a) to identify gender differences in sexual behaviors and sexual dysfunction among Portuguese men and women within different classes of BMI; and (b) to explore the association between BMI and sexual dysfunction by using the new DSM-5 severity criteria.

Materials and methodsSetting and participantsThis article draws on data from a wider study, the Sexual Observational Study (SEXOS), which was conducted in primary healthcare centers in Lisbon, Portugal, between January and April 2011.20 Male and female users of the collaborating centers, aged 18–80 years old (n=323), were systematically invited to a standardized interview. This consisted of two parts: (a) a face-to-face interview on sociodemographic and health variables, and a sexual health inquiry, including the self-report of sexual problems; followed by (b) a self-completed questionnaire assessing sexual activity, knowledge, practices and beliefs about sexual problems and their treatment. Questionnaires aimed at reducing potential response bias arising from the disclosure of sensitive information to the interviewers.21 The entire interviews were conducted in a private room of the participating centers by male interviewers for male users and by female interviewers for female participants. The setting was made socially acceptable and appropriate, so the participants were comfortable in discussing aspects of their sexuality. The interviewers were psychologists with special training on the topics under study.22,23

Instruments and outcome measuresSociodemographic characteristics collected included gender, age, marital status, educational level, and employment status. Information on height and weight was collected and used to determine BMI, which is the most used measure to assess body size in research.12 BMI is defined as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). Participants were grouped into four BMI classes following World Health Organization4: underweight, BMI<18.5kg/m2; normal weight, BMI 18.5–25.0kg/m2; overweight BMI 25.0–30.0kg/m2; and obesity BMI≥30.0kg/m2.

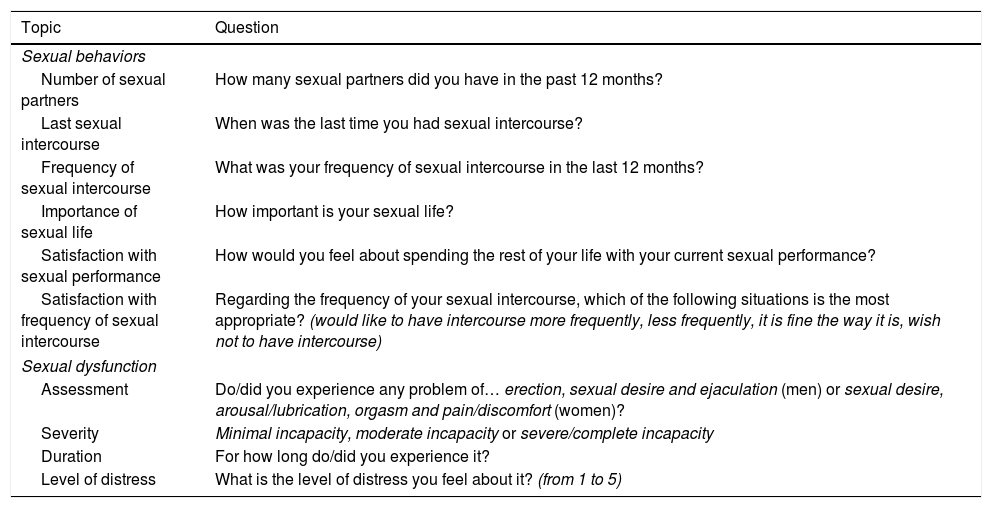

Self-completed questionnaires contained six questions on sexual behaviors and four questions on SD, as presented in Table 1. For those participants who reported sexual difficulties, additional information was gathered regarding the severity, duration and associated distress, as recommended by DSM-5.14 Accordingly, participants who reported one or more sexual difficulties for more than six months, ranging from moderate to severe incapacity, and that caused a distress level of three or more (from 1 to 5) were diagnosed with SD.

Questionnaire used in the analysis of sexual behaviors and sexual dysfunction.

| Topic | Question |

|---|---|

| Sexual behaviors | |

| Number of sexual partners | How many sexual partners did you have in the past 12 months? |

| Last sexual intercourse | When was the last time you had sexual intercourse? |

| Frequency of sexual intercourse | What was your frequency of sexual intercourse in the last 12 months? |

| Importance of sexual life | How important is your sexual life? |

| Satisfaction with sexual performance | How would you feel about spending the rest of your life with your current sexual performance? |

| Satisfaction with frequency of sexual intercourse | Regarding the frequency of your sexual intercourse, which of the following situations is the most appropriate? (would like to have intercourse more frequently, less frequently, it is fine the way it is, wish not to have intercourse) |

| Sexual dysfunction | |

| Assessment | Do/did you experience any problem of… erection, sexual desire and ejaculation (men) or sexual desire, arousal/lubrication, orgasm and pain/discomfort (women)? |

| Severity | Minimal incapacity, moderate incapacity or severe/complete incapacity |

| Duration | For how long do/did you experience it? |

| Level of distress | What is the level of distress you feel about it? (from 1 to 5) |

For comparison purposes, sexual function was also assessed using the following standardized self-completion questionnaires: the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) for men and the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) for women. For the erectile dysfunction domain, a cut-off score of 25 was used for IIEF, whereas a cut-off score of 29 was defined for overall female sexual dysfunction following FSFI.24 These are the most widely used and validated self-completion questionnaires for measuring sexual function.25 Moreover, the validated Portuguese versions of both have good psychometric properties,24,26,27 as was also the case for this sample. Both instruments had good internal reliability, with standardized Cronbach's α of 0.95 for the IIEF and 0.92 for the FSFI.

Statistical analysisData was coded onto SPSS 20.0 database and checked for accuracy. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05 for all tests. Differences between men and women were assessed using Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests, and Non-Parametric Mann–Whitney test. Further statistical analyses were performed separately for men and women to explore gender differences in the association between BMI classes and sexual behaviors. Chi-square and Fisher's exact tests and Non-Parametric Kruskal–Wallis test were used to compare sexual activity between BMI groups. Logistic regression was used to assess the association between BMI scale (continuous variable) and SD diagnosis following the cut-off points previously defined (dichotomous variable) while considering other explanatory variables. Therefore, unadjusted and adjusted models for age and marital status were conducted (with odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals).

Ethical considerationsBefore enrollment in the study, each participant signed an informed consent. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Lisbon Health Region and Tagus Valley. Permission from the Portuguese Data Protection Authority was also obtained.

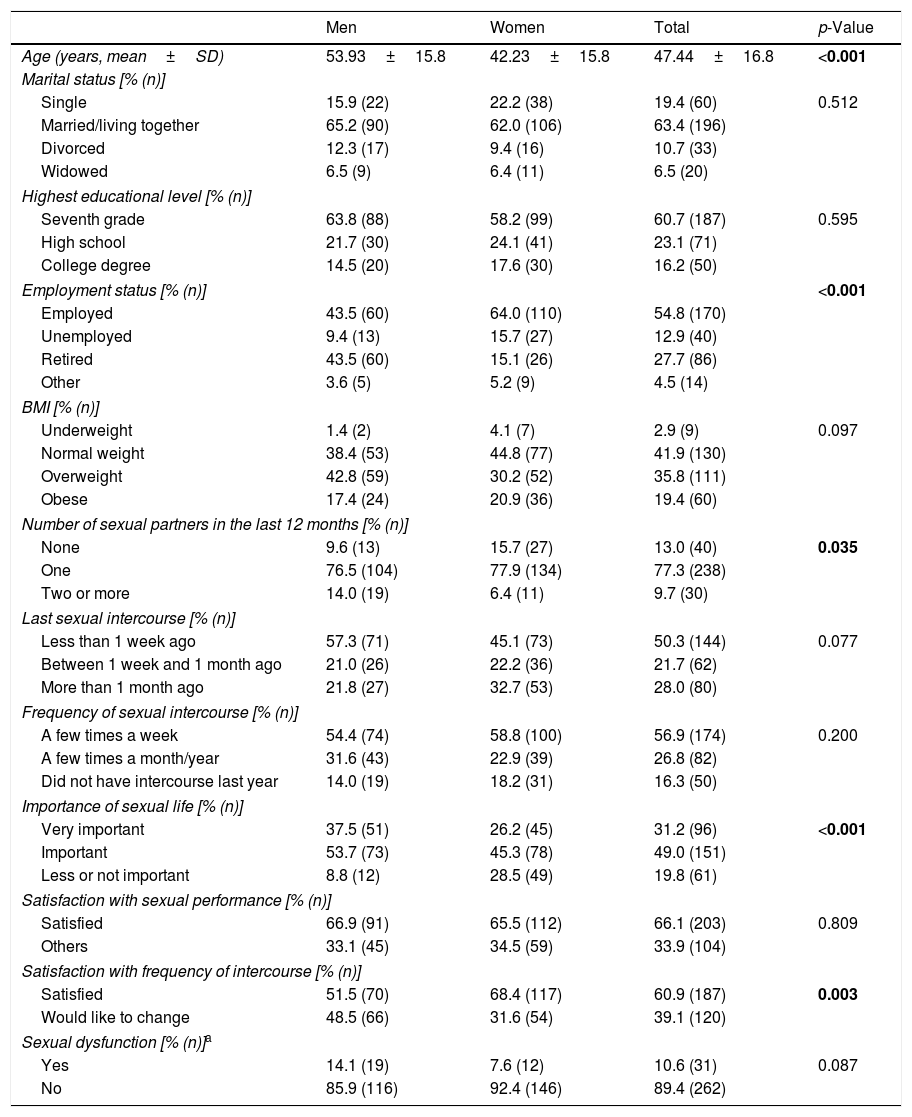

ResultsSociodemographic characterizationThe initial sample contained 323 individuals, 310 (96.0%) of whom completed the information on weight and height and thus, constituted the final group for analyses: 138 (44.5%) men and 172 (55.5%) women. This was a diverse sample for sociodemographic characteristics (Table 2). Significant differences were found between men and women regarding age and employment status. Women were, on average, 11 years younger than men (p<0.001) and unlike men, they were mainly employed (64.0%, p<0.001).

Sociodemographic characterization of the sample and data on sexual behaviors and sexual dysfunction for men and women (non-imputed data).

| Men | Women | Total | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean±SD) | 53.93±15.8 | 42.23±15.8 | 47.44±16.8 | <0.001 |

| Marital status [% (n)] | ||||

| Single | 15.9 (22) | 22.2 (38) | 19.4 (60) | 0.512 |

| Married/living together | 65.2 (90) | 62.0 (106) | 63.4 (196) | |

| Divorced | 12.3 (17) | 9.4 (16) | 10.7 (33) | |

| Widowed | 6.5 (9) | 6.4 (11) | 6.5 (20) | |

| Highest educational level [% (n)] | ||||

| Seventh grade | 63.8 (88) | 58.2 (99) | 60.7 (187) | 0.595 |

| High school | 21.7 (30) | 24.1 (41) | 23.1 (71) | |

| College degree | 14.5 (20) | 17.6 (30) | 16.2 (50) | |

| Employment status [% (n)] | <0.001 | |||

| Employed | 43.5 (60) | 64.0 (110) | 54.8 (170) | |

| Unemployed | 9.4 (13) | 15.7 (27) | 12.9 (40) | |

| Retired | 43.5 (60) | 15.1 (26) | 27.7 (86) | |

| Other | 3.6 (5) | 5.2 (9) | 4.5 (14) | |

| BMI [% (n)] | ||||

| Underweight | 1.4 (2) | 4.1 (7) | 2.9 (9) | 0.097 |

| Normal weight | 38.4 (53) | 44.8 (77) | 41.9 (130) | |

| Overweight | 42.8 (59) | 30.2 (52) | 35.8 (111) | |

| Obese | 17.4 (24) | 20.9 (36) | 19.4 (60) | |

| Number of sexual partners in the last 12 months [% (n)] | ||||

| None | 9.6 (13) | 15.7 (27) | 13.0 (40) | 0.035 |

| One | 76.5 (104) | 77.9 (134) | 77.3 (238) | |

| Two or more | 14.0 (19) | 6.4 (11) | 9.7 (30) | |

| Last sexual intercourse [% (n)] | ||||

| Less than 1 week ago | 57.3 (71) | 45.1 (73) | 50.3 (144) | 0.077 |

| Between 1 week and 1 month ago | 21.0 (26) | 22.2 (36) | 21.7 (62) | |

| More than 1 month ago | 21.8 (27) | 32.7 (53) | 28.0 (80) | |

| Frequency of sexual intercourse [% (n)] | ||||

| A few times a week | 54.4 (74) | 58.8 (100) | 56.9 (174) | 0.200 |

| A few times a month/year | 31.6 (43) | 22.9 (39) | 26.8 (82) | |

| Did not have intercourse last year | 14.0 (19) | 18.2 (31) | 16.3 (50) | |

| Importance of sexual life [% (n)] | ||||

| Very important | 37.5 (51) | 26.2 (45) | 31.2 (96) | <0.001 |

| Important | 53.7 (73) | 45.3 (78) | 49.0 (151) | |

| Less or not important | 8.8 (12) | 28.5 (49) | 19.8 (61) | |

| Satisfaction with sexual performance [% (n)] | ||||

| Satisfied | 66.9 (91) | 65.5 (112) | 66.1 (203) | 0.809 |

| Others | 33.1 (45) | 34.5 (59) | 33.9 (104) | |

| Satisfaction with frequency of intercourse [% (n)] | ||||

| Satisfied | 51.5 (70) | 68.4 (117) | 60.9 (187) | 0.003 |

| Would like to change | 48.5 (66) | 31.6 (54) | 39.1 (120) | |

| Sexual dysfunction [% (n)]a | ||||

| Yes | 14.1 (19) | 7.6 (12) | 10.6 (31) | 0.087 |

| No | 85.9 (116) | 92.4 (146) | 89.4 (262) | |

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; statistically significant differences are in bold (p<0.05).

No statistically significant differences were found in the mean values of BMI between genders. Overall, 19.4% of the participants were obese, 35.8% were overweight and 41.9% were normal weight. The percentage of participants classified as underweight was very low (2.9%). In order to not decrease the statistical power due to a reduced sample size, underweight and normal weight participants were grouped for further analyses, which only considered three BMI categories: under/normal weight, overweight and obesity.

BMI and age were associated in both genders: under/normal weight individuals were significantly younger (men: 49.62±17.30 years old; women: 35.35±13.82 years old; p<0.05) than those overweight (men: 57.54±15.00 years old; women: 46.23±13.93 years old) and obese (men: 54.96±11.79 years old; women: 52.19±15.78 years old). Differences in sociodemographic variables among BMI classes were only found for women (p<0.001). Obese women were older, mainly married or living together (75.0%), and obtained a lower educational level (82.9%) than under/normal weight (39.0%) and overweight (71.7%) counterparts. Although obese women were mainly employed (41.7%), this percentage was higher in the under/normal weight sample (71.1%; p=0.004).

BMI and sexual dysfunctionThe majority of the participants (76.5%) had only one partner in the previous 12 months. Most men and women were sexually active: nearly half reported having had intercourse in the previous week (50.3%) and 56.9% stated having intercourse a few times a week. Significantly more women (15.7%) than men (9.6%) referred not having a partner in the previous year, whereas more men (14.0%) than women (6.4%) revealed having two or more partners during the same period of time (p=0.035).

With regards to the importance attributed to sexual life, significantly more women (28.5%) considered sexual life of little or no importance (p<0.001). In contrast, more men (48.5%) assumed they would like to change their frequency of sexual intercourse (p=0.003). No differences between genders were found regarding the diagnosis of SD following DSM-5 criteria (Table 2).

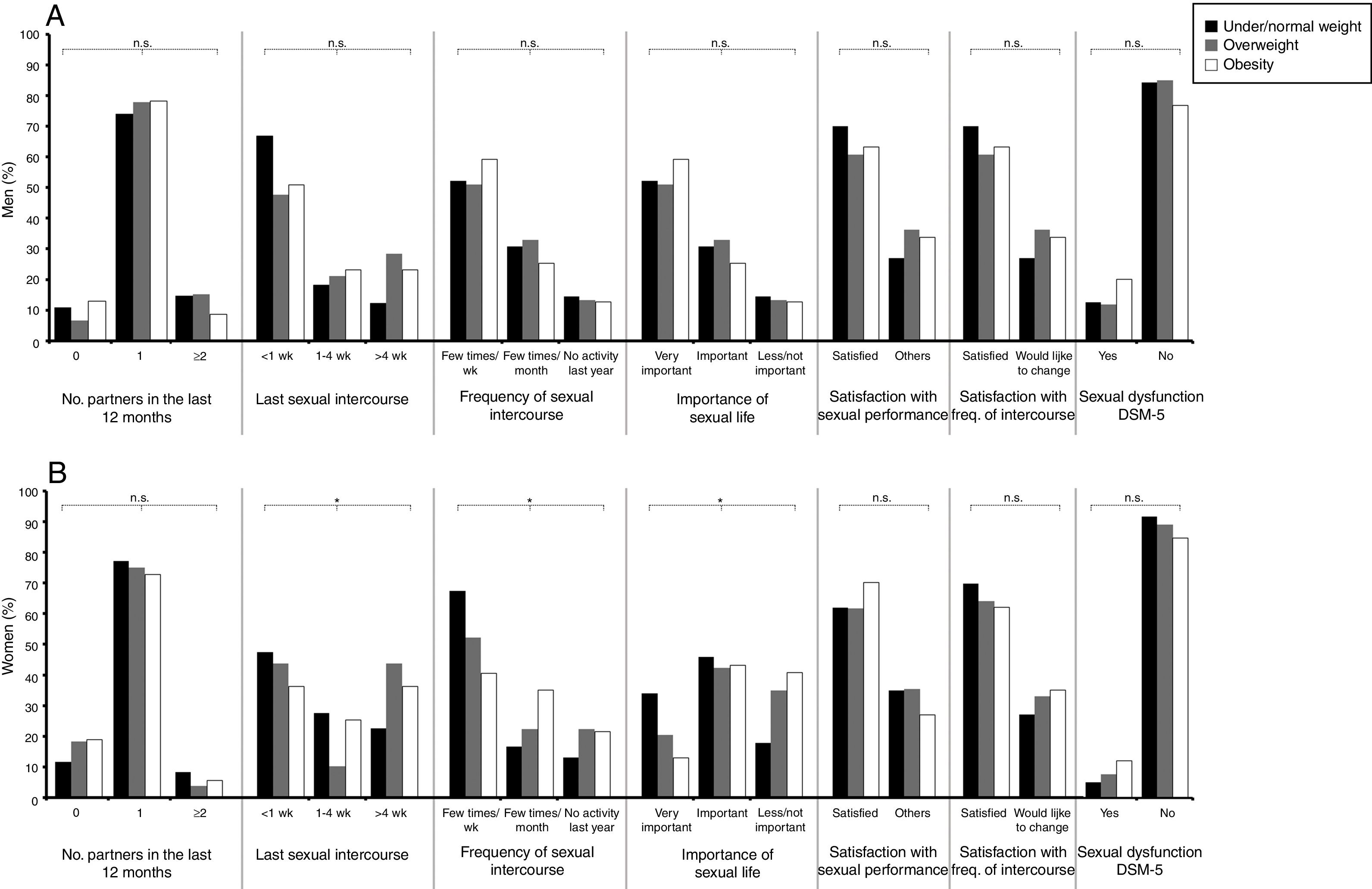

Concerning sexual behaviors in men (Fig. 1A), only SD as measured by IIEF differed among BMI classes (p=0.012). Under/normal weight men had a higher IIEF score (61.55±12.73) than those overweight (53.33±18.24) and obese (55.47±14.79). In contrast, no differences among BMI classes in the diagnosis of SD were found using DSM-5 criteria.

On the other hand, several differences were found among BMI classes and sexual behaviors in women (Fig. 1B). Obese and overweight women reported less sexual activity than those of normal weight. The number of women who stated having had sexual intercourse in the previous week was lower when BMI was higher (p=0.040). A similar tendency was found in the number of women who reported having sexual intercourse a few times a week (p=0.048). Less obese women considered sexual life very important (13.9%, p=0.021) than those overweight (20.8%) and normal weight (34.9%).

Concerning sexual function measured by the FSFI, its score was significantly lower (p=0.007) for overweight (28.76±5.29) and obese (27.80±5.34) than normal weight women (30.73±4.58). Similar to men, no differences in the diagnosis of SD as assessed by DSM-5 were found.

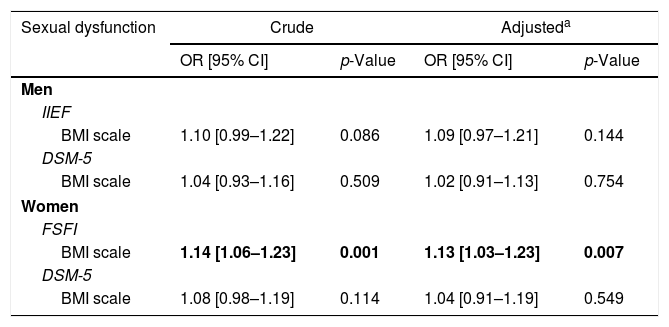

The results of the logistic regression are consistent with the ones presented above. No significant effects of BMI scale on SD according to DSM-5 for men and women were detected using unadjusted and adjusted models for age and marital status (Table 3). However, BMI scale was found to have an effect on SD only for women when FSFI score was used (unadjusted model, OR=1.14, 95% CI: 1.06–1.23).

Results of the logistic regression investigating the association between BMI scale and sexual dysfunction.

| Sexual dysfunction | Crude | Adjusteda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | |

| Men | ||||

| IIEF | ||||

| BMI scale | 1.10 [0.99–1.22] | 0.086 | 1.09 [0.97–1.21] | 0.144 |

| DSM-5 | ||||

| BMI scale | 1.04 [0.93–1.16] | 0.509 | 1.02 [0.91–1.13] | 0.754 |

| Women | ||||

| FSFI | ||||

| BMI scale | 1.14 [1.06–1.23] | 0.001 | 1.13 [1.03–1.23] | 0.007 |

| DSM-5 | ||||

| BMI scale | 1.08 [0.98–1.19] | 0.114 | 1.04 [0.91–1.19] | 0.549 |

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; IIEF: International Index of Erectile Function; FSFI: Female Sexual Function Index; OR: Odds Ratio and the corresponding 95% CI: Confidence Interval; statistically significant differences are in bold (p<0.05).

The main goal of this study was to identify differences in sexual behaviors, sexual satisfaction and SD among Portuguese men and women of different BMI classes. Results herein show that overweight and obese women report less sexual activity and satisfaction than those of normal weight. Moreover, differences among BMI classes regarding the assessment of SD were only detected for women through FSFI, but not following IIEF for men or the new classification of DSM-5 for both genders.

Obesity has been previously described as affecting sexual experiences for both men and women.15,28 Our findings support this proposition and go further by revealing that women's sexuality is more likely to be affected by overweight than men's. This result is in line with others previously reported in the literature.10 A deeper understanding on female sexuality requires the complex interplay between social and medical factors to be taken into account. In fact, it has been reported that the variation of women's sexual satisfaction is better explained through social desire variables (e.g., intimacy, emotional closeness, stress, sexual knowledge) than by SD alone.29

Differences detected between men and women emphasize the relevance of taking into account several variables when considering the relation between BMI and sexual behaviors. For example, age has been described as a mediator of the effects of BMI.9 However, the small sample size of the present study did not allow the potential mediator effect of age to be ascertained. Furthermore, and to our knowledge, no data examining the relation between body image (i.e., self-perception, thoughts and feelings about own body) and BMI has been previously collected. Men and women with greater body fat accumulation are more likely to have a simultaneously poorer affective body image and body image specific to the sexual encounter (i.e., body appearance cognitive distraction). However, this relation is complex and differs between men and women.30,31 Thus, further investigation on the relation between body image and BMI is desirable.31

The difference found between SD measured by the international index FSFI and DSM-5 is the most interesting result of this study. Scores of FSFI reveal an impact of body weight on sexual function that was not detected when DSM-5 based on self-reports was used. While the limitations of IIEF and FSFI have been previously discussed,32 DSM-5 new criteria reflect a less strict medical view on sexuality of both men and women. Following DSM-5, the assessment of sexual function moved forward to focus on the individual's sexual experiences, and the diagnosis of SD occurs whenever individuals experience persistent, frequent and distressing claims.19 Altogether, the three morbidity criteria allow the distinction between situations of transient and persistent sexual dysfunction, thus resulting in a more precise diagnosis of SD.

Strengths and limitationsThe main strength of this study is the use of DSM-5 criteria to assess the relation between body weight and SD, for the first time, among Portuguese men and women. Furthermore, the sample of the present study had a good level of diversity in terms of sociodemographic characteristics, even between genders (e.g., women were younger than men), a limitation pointed out on most of the previous studies in this field.9 However, the small sample size allied to data derived from one specific region in Portugal precluded the usage of more robust statistical methods, this being the main limitation of the present study. Additionally, this paper draws on data from a wider study, which somehow limited the operationalization of DSM-5 definition. Finally, height and weight were self-reported by the participants. Previous research has reported a discrepancy between objective and subjective measures of body weight, which might have contributed some bias to the calculation of BMI.33

Final considerationsAn effect of BMI on sexual function for women was noted, even despite the already discussed limitations of the undertaken analysis. Body size is differently experienced by each person and consequently, has an impact on how their own sexuality is lived as well. The new DSM-5 criteria go beyond the strict medical model and focus on the individual's experiences, which allow a better understanding on the relation between body size and sexuality. Indeed, the assessment and management of SD would greatly benefit from the adoption of approaches orientated to the individualized experience of sexuality. Future studies specifically designed to accommodate DSM-5 new definition, with nationally representative samples and investigating variables associated with intimacy and sexuality (body image satisfaction, self-esteem, and body appearance cognitive distraction) are desirable and would allow a more precise understanding on the effects of body weight in sexual behaviors and SD.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

FundingThis study was supported by a grant from AstraZeneca Foundation. The funding source did not have any role in study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; preparation, review and submission of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

We would like to thank ACES-Odivelas Health Units, SEXOS Study Research Team, and to all men and women who kindly participated in the study.