Circumcision is one of the oldest elective surgical interventions in the history of mankind. Though many studies have been conducted on the surgical complications of circumcision, the potential effects on the mental state of the children has not been satisfactorily reviewed. In this prospective study, we analyzed potential effects of circumcision on their mental state, anxiety levels and moods using updated scales.

Material and methodsOne hundred and two male children aged between 6 and 8 and their families were included in the study. Children with their families completed sociodemographic data form Anxiety Sensitivity Index For Children, the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), Depression Scale for Children during the preoperative period. All children received oral 0.5mg/kg midazolam as a premedication before circumcision procedure. Circumcisions were performed under general anesthesia in the operating room. During the 6th week of the postoperative period, the children and their families were returned to the facility and parents were asked to complete the questionnaire again.

ResultsMean score of the preoperative depression scale was statistically and significantly higher than the mean postoperative depression scale score (P=0.001; P<0.01). Pre-, and post-operative depression scale scores of the children with divorced parents showed a higher statistical significance higher than those of the children whose family togetherness was not broken (P=0.001; P<0.01).

ConclusionBefore circumcision, in all children to be circumcised a tendency to depression and an increase in anxiety were observed regardless of the presence of subgroups. At the end of the study, it was found that low socioeconomic level, disrupted family dynamic, and/or the presence of mental disease in a parent could increase the predisposition to pre and post-operative depression. At this stage the main factor determining the level of anxiety is the procedure of circumcision itself.

La circuncisión es una de las intervenciones quirúrgicas electivas más antiguas de la historia de la humanidad. Aunque muchos estudios se han realizado sobre las complicaciones quirúrgicas de la circuncisión, su efecto potencial sobre el estado mental de los niños no se ha aclarado mucho. En este estudio prospectivo se analizaron los efectos potenciales de la circuncisión en su estado mental, los niveles de ansiedad y estados de ánimo que por medio de escalas actualizadas.

Material y métodosCiento dos niños varones de edades comprendidas entre los 6 y los 8 años y sus familias fueron incluidos en el estudio. Los niños con sus familias completaron el formulario de datos sociodemográficos Ansiedad Índice de Sensibilidad Para los niños, Capacidades y Dificultades (SDQ), escala de depresión para los niños durante el período preoperatorio. Todos los niños recibieron por vía oral 0,5mg/kg de midazolam como premedicación antes de procedimiento de circuncisión. Las circuncisiones se realizaron bajo anestesia general en la sala de operaciones. Durante la sexta semana del postoperatorio, los niños y sus familias regresaron y completaron las mismas encuestas una vez más.

ResultadosLa media de puntuación de la escala de depresión preoperatoria fue estadística y significativamente más alta que la puntuación media postoperatoria escala de depresión (p=0,001; p<0,01). Las puntuaciones pre y post operatorias en la escala de depresión de los niños con padres divorciados mostraron una mayor significación estadística que las de los niños cuyo núcleo familiar no estaba roto (p=0,001; p<0,01).

ConclusiónAntes de la circuncisión, en todos los niños que iban a ser circuncidados se aprecia una tendencia a la depresión y el aumento de la ansiedad, independientemente de la presencia de subgrupos. Una vez concluida la investigación, se observó que un bajo nivel de ingresos, una dinámica familiar desequilibrada y/o la presencia de un trastorno mental en un progenitor podrían predisponer a la depresión pre y postoperatoria. En esta etapa el factor principal que determina el nivel de ansiedad es el procedimiento de la circuncisión sí mismo.

Circumcision is one of the oldest elective surgical interventions in the history of mankind. Its first applications were related to a religious ritual, however it has become a routine neonatal surgery performed in the USA and European countries in consideration of its beneficial effects on hygiene and protection from cancer. Nowadays every year 13.3 million boys have been circumcised.1 According to World Health Organization data in 30–33% of the male population aged ≥15 years have been circumcised. In Islamic countries circumcision has higher incidence rates. In Turkey religious and cultural factors take the lead. Contrary to western populations, in Turkey circumcision is performed at an average age of 7 years. The operation of circumcision is described in a way as to move from childhood to adolescence, which becomes a positive motivator for the children.2

Health is defined as a physical, psychological and social well-being. Though many studies have been conducted on the surgical complications of circumcision, the potential effects on the mental state of the children has not been satisfactorily reviewed. Besides the relationship between these potential effects, social environment and socioeconomic state is another matter of curiosity.

Our purpose for this prospective study was to analyze the potential effects of circumcision on a child's mental state, anxiety level, and mood by taking the social environment into consideration and using updated scales.

Materials and methodsHundred and two boys aged between 6 and 8 years, and their families were included in the study. The children with their families completed socio-demographic data form, Anxiety Sensitivity Index For Children, The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), Depression Scale for Children during the preoperative period. Parents were asked about any previous application history of psychiatry outpatient clinics (does not matter if they had taken any medical treatment or not). All children received oral 0.5mg/kg midazolam as a premedication before circumcision procedure. Circumcisions were performed under general anesthesia in the operating room. None of the children were hospitalized after the circumcision process and all of them were discharged at the 6th hour of the postoperative.

During the 6th week of the postoperative, the children and their families were returned to the facility and parents were asked to complete the questionnaires (Anxiety Sensitivity Index For Children, The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), Depression Scale) again. Scoring of the scales was performed according to relevant literature information, and the results were subjected to statistical analysis. Anxiety Sensitivity Index for Children consists of 20 questions to determine their anxiety levels. This scale was originally described by Spielberger in the year 1976.3 Besides each item is evaluated, ranked, and calculated based on the symptomatic severity of the anxiety as 0,1, and 2 points, Depression Scale for Children was firstly used by Weissman et al., which consists 20 questions in all. Its scoring was performed, based on the symptomatic severity of depression as 0, 1, 2, and 3 points. Cut-off value of the final score for the diagnosis of depression was accepted as 15 points.4

Ethical standardThese study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Regional Ethical Vetting Board (Istanbul) and performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Statistical analysisFor statistical evaluation of the data obtained in the study, IBM SPSS Statistics 22 program was used. Fitness of parameters to normal distribution was evaluated using Shapiro–Wilks test. For intergroup comparisons of quantitative data with non-normal distribution, Mann–Whitney U test was used. For intergroup comparisons of the parameters with non-normal distribution, Kruskal–Wallis test, and for the identification of the group, which differed from others, Mann–Whitney U test were used. For the pre, and post-operative comparisons of parameters with normal distribution paired sample t test, and for those with non-normal distribution Wilcoxon-signed test were used. Significance of data was evaluated at P<0.05.

ResultsMean score of the preoperative depression scale was statistically significantly higher than mean postoperative depression scale score (P: 0.001; P<0.01).

A statistically significant difference between mean scores of pre, and postoperative strengths, and difficulties questionnaire of the children was not found (P>0.05).

Mean total score of the preoperative anxiety sensitivity index (ASI) for children was statistically significantly higher than mean total postoperative ASI score (P: 0.001; P<0.01).

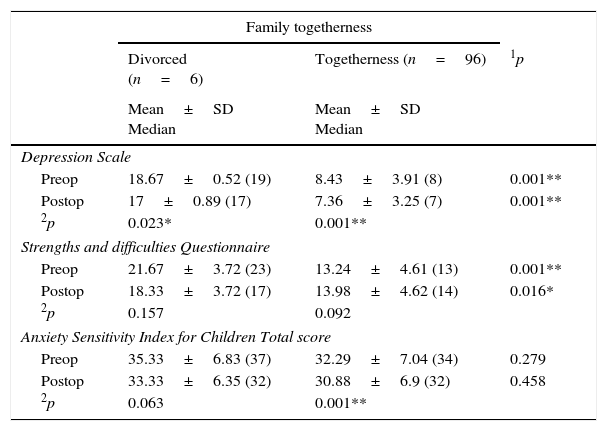

Pre, and post-operative depression scale scores of the children with divorced parents were statistically significantly higher than those of the children whose family togetherness was not broken (P: 0.001; P<0.01).

Preoperative strengths, and difficulties questionnaire scores of the children of the divorced parents were statistically significantly higher than the children whose family integrity was not broken (P: 0.001; P<0.01).

The Strengths, and difficulties questionnaire scores of the children of divorced parents were found to be statistically significantly higher than the children whose family togetherness was not broken (P: 0.016; P<0.05).

A statistically significant difference was not detected between total pre, and postoperative anxiety sensitivity indices with respect to family togetherness (P>0.05) (Table 1).

Evaluation of pre- and post-operative scale scores according to family togetherness.

| Family togetherness | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Divorced (n=6) | Togetherness (n=96) | 1p | |

| Mean±SD Median | Mean±SD Median | ||

| Depression Scale | |||

| Preop | 18.67±0.52 (19) | 8.43±3.91 (8) | 0.001** |

| Postop | 17±0.89 (17) | 7.36±3.25 (7) | 0.001** |

| 2p | 0.023* | 0.001** | |

| Strengths and difficulties Questionnaire | |||

| Preop | 21.67±3.72 (23) | 13.24±4.61 (13) | 0.001** |

| Postop | 18.33±3.72 (17) | 13.98±4.62 (14) | 0.016* |

| 2p | 0.157 | 0.092 | |

| Anxiety Sensitivity Index for Children Total score | |||

| Preop | 35.33±6.83 (37) | 32.29±7.04 (34) | 0.279 |

| Postop | 33.33±6.35 (32) | 30.88±6.9 (32) | 0.458 |

| 2p | 0.063 | 0.001** | |

1 Preoperative.

2 Postoperative.

*p < 0.05: statistically significant difference (less than 5% chance of being wrong).

**p < 0.01: statistically highly significant difference (less than 1% chance of being wrong).

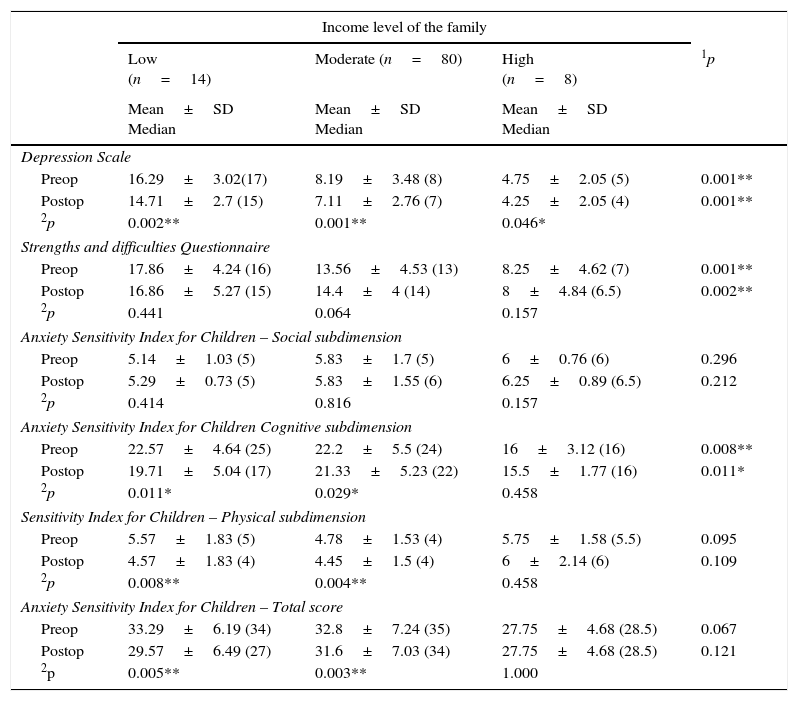

A statistically significant difference was not found between pre, and post-operative depression scale scores with respect to family income levels (P: 0.001; P<0.01). As a result of pairwise comparisons performed so as to determine in which income level the source of difference arises, preoperative depression scale scores of the children of the low-income families were found to be statistically significantly higher than the children of families with moderate (P: 0.001), and good (P: 0.001) income levels (P<0.01).

Preoperative strengths, and difficulties questionnaire scores of the children of different family income levels were statistically significantly different (P: 0.001; P<0.01).

Postoperative strengths, and difficulties questionnaire scores of the children of the families with different income levels were statistically significantly different (P: 0.002; P<0.01).

A statistically significant difference was not detected between total pre, and post-operative anxiety index scores among children of the families with different income levels (P>0.05). However, a statistically significant difference was detected between pre, and post-operative cognitive sub-dimension scores of the anxiety sensitivity indices of the children belonging to various family income levels (Table 2).

Evaluation of pre- and post-operative scale scores based on income levels of the families.

| Income level of the family | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n=14) | Moderate (n=80) | High (n=8) | 1p | |

| Mean±SD Median | Mean±SD Median | Mean±SD Median | ||

| Depression Scale | ||||

| Preop | 16.29±3.02(17) | 8.19±3.48 (8) | 4.75±2.05 (5) | 0.001** |

| Postop | 14.71±2.7 (15) | 7.11±2.76 (7) | 4.25±2.05 (4) | 0.001** |

| 2p | 0.002** | 0.001** | 0.046* | |

| Strengths and difficulties Questionnaire | ||||

| Preop | 17.86±4.24 (16) | 13.56±4.53 (13) | 8.25±4.62 (7) | 0.001** |

| Postop | 16.86±5.27 (15) | 14.4±4 (14) | 8±4.84 (6.5) | 0.002** |

| 2p | 0.441 | 0.064 | 0.157 | |

| Anxiety Sensitivity Index for Children – Social subdimension | ||||

| Preop | 5.14±1.03 (5) | 5.83±1.7 (5) | 6±0.76 (6) | 0.296 |

| Postop | 5.29±0.73 (5) | 5.83±1.55 (6) | 6.25±0.89 (6.5) | 0.212 |

| 2p | 0.414 | 0.816 | 0.157 | |

| Anxiety Sensitivity Index for Children Cognitive subdimension | ||||

| Preop | 22.57±4.64 (25) | 22.2±5.5 (24) | 16±3.12 (16) | 0.008** |

| Postop | 19.71±5.04 (17) | 21.33±5.23 (22) | 15.5±1.77 (16) | 0.011* |

| 2p | 0.011* | 0.029* | 0.458 | |

| Sensitivity Index for Children – Physical subdimension | ||||

| Preop | 5.57±1.83 (5) | 4.78±1.53 (4) | 5.75±1.58 (5.5) | 0.095 |

| Postop | 4.57±1.83 (4) | 4.45±1.5 (4) | 6±2.14 (6) | 0.109 |

| 2p | 0.008** | 0.004** | 0.458 | |

| Anxiety Sensitivity Index for Children – Total score | ||||

| Preop | 33.29±6.19 (34) | 32.8±7.24 (35) | 27.75±4.68 (28.5) | 0.067 |

| Postop | 29.57±6.49 (27) | 31.6±7.03 (34) | 27.75±4.68 (28.5) | 0.121 |

| 2p | 0.005** | 0.003** | 1.000 | |

1 Preoperative.

2 Postoperative.

* p < 0.05: statistically significant difference (less than 5% chance of being wrong).

** p < 0.01: statistically highly significant difference (less than 1% chance of being wrong).

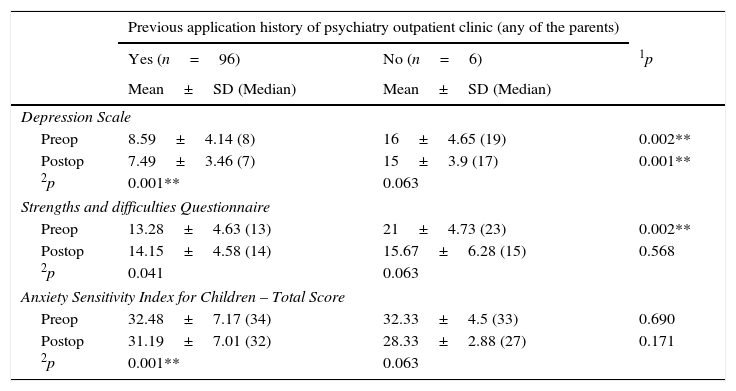

Preoperative depression scale scores of the children whose one or two parents had a previous application history of psychiatry outpatient clinic were statistically significantly higher than those without any psychiatric history (P: 0.002; P<0.01).

Postoperative depression scale scores of the children whose one or two parents had a previous application history of psychiatry outpatient clinic were statistically significantly higher than those without any psychiatric history (P: 0.001; P<0.01).

Preoperative strengths, and difficulties questionnaire scores of the children whose one or two parents had a previous application history of psychiatry outpatient clinic were statistically significantly higher than those without any psychiatric history (P: 0.002; P<0.01).

Postoperative strengths, and difficulties questionnaire scores of the children did not differ statistically significantly whether their parents had a previous application history of psychiatry outpatient clinic or not (P>0.05).

A statistically significant difference was not found between total pre, and postoperative anxiety sensitivity index scores when presence of a previous application history of psychiatry outpatient clinic was taken into consideration (P>0.05) (Table 3).

Evaluation of pre- and post-operative scale scores based on previous application history of psychiatry outpatient clinic (any of the parents).

| Previous application history of psychiatry outpatient clinic (any of the parents) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=96) | No (n=6) | 1p | |

| Mean±SD (Median) | Mean±SD (Median) | ||

| Depression Scale | |||

| Preop | 8.59±4.14 (8) | 16±4.65 (19) | 0.002** |

| Postop | 7.49±3.46 (7) | 15±3.9 (17) | 0.001** |

| 2p | 0.001** | 0.063 | |

| Strengths and difficulties Questionnaire | |||

| Preop | 13.28±4.63 (13) | 21±4.73 (23) | 0.002** |

| Postop | 14.15±4.58 (14) | 15.67±6.28 (15) | 0.568 |

| 2p | 0.041 | 0.063 | |

| Anxiety Sensitivity Index for Children – Total Score | |||

| Preop | 32.48±7.17 (34) | 32.33±4.5 (33) | 0.690 |

| Postop | 31.19±7.01 (32) | 28.33±2.88 (27) | 0.171 |

| 2p | 0.001** | 0.063 | |

1 Preoperative.

2 Postoperative.

* p < 0.05: statistically significant difference (less than 5% chance of being wrong).

** p < 0.01: statistically highly significant difference (less than 1% chance of being wrong).

Circumcision is one of the oldest elective surgical interventions in the history of mankind. Its first applications were related to a religious ritual, however it has become a routine neonatal surgery performed in the USA, and European countries in consideration of its beneficial effects on hygiene, and protection from cancer.5,6 Though circumcision is the most frequently performed elective surgical intervention in the whole world, its numerous short, and long-term potential complications should not be forgotten. Pain, difficult wound healing, bleeding, infection, psychological trauma, and high cost rank on top.7,8 In the literature, some complications of the circumcision including even death can be seen. Probability of decrease in sexual satisfaction both in men, and women because of erectile tissue loss has been reported in the literature.7–10

Though numerous investigations have been conducted on early postoperative surgery complications of circumcision performed during childhood, adequate numbers of analytical studies have not been performed on its long-term non-surgical complications. In a study, which was performed on 476 circumcised male children, complications were reported in 8 (1.7%) children, and 3 of which were related to anesthetic complications.11 The most frequently reported surgical complication was excessive bleeding (0.6%).12 In a prospective cohort study performed on 700 male circumcised children, excessive bleeding (2.2%), and postoperative infection (1.3%) were seen. However in circumcisions performed by specialists out of the hospital setting excessive bleeding, and postoperative infection were reported in 3.6, and 2.7% of the circumcisions, respectively.13 In a study performed in Iran long-term surgical complications were seen in 7.4% of circumcisions performed which included redundant (3.6%) or excessively excised (1.3%) foreskin, and meatal stenosis (0.9%).14

Health is defined as a general physical, psychological and social well-being. Physical, and psychological traumatic events are major causes of instability in the life of the children It has negative effects on cognitive abilities, academic, and social success, and daily behaviors.15 Circumcisions have a potential factor to create similar effects on male children in their preschool period. Problems related to mental, and psychological health are prevalently seen important issues during childhood, and adolescence,16–20 and nearly 50% of all mental health problems seen in adults have an onset in the adolescence period.21 Anxiety disorder, depression, trauma-related symptoms, and some behavioral problems are prevalently seen in examples, which can be diagnosed, and treated during childhood, and adolescence.

While examining psychological state of children, it is very important to make objective evaluations using globally accepted, and updated scales. At this point we used 3 scales, which have been advocated in literature studies, namely anxiety sensitivity index for children, strengths, difficulties questionnaire, and depression scale for children.

State anxiety defines how an individual feels her/himself, and the way he/she reflects his/her feelings. Level of anxiety is related to the apprehension felt by an individual during a certain period of time, and the way it is reflected outward with the pressure of external factors or under certain circumstances. As has been reported in various studies, planning of medical intervention, and surgical process have a strong impact on the child's concerns, and worries.22–24 Incidence rates of anxiety disorder vary in different age groups (school age, 6–12 years; 3–5% and adolescents 13–18 years: 10–19%)25,26 and these rates increase day by day.27 Anxiety is the most frequently reported psychological symptom. Besides, especially in small children unusual symptoms as muscle strain, headache, stomachache, and fits of anger can be indicators of anxiety.28 Especially pediatric patients aged 6–12 years have worries about their body integrities. They wonder about the details, and duration of the operation, the time when they can stand up and walk, and their self-image after the operation.

At this point, the questions of the children should be responded honestly. Procedure should be described step-by-step using audiovisual models. Thus anxiety level of the child can be lowered.29–31 Besides pharmacological, and non-pharmacological means or combination of them can be used.32 Some sedative medications as midazolam can be used preoperatively to decrease the levels of preoperative anxiety.33,34 Based on the statistical results of our study, disregarding what types of subgroups were present, the mean of preoperative anxiety sensitivity index scores was detected remarkably higher than the mean of postoperative anxiety sensitivity index scores. Similarly, in a study performed, a statistically significant difference was detected between pre, and post-operative anxiety levels. In the outcome evaluation of the authors, only verbal information given in the hospital to the children was not found to be adequately enlightening, on the contrary it had a negative effect on the anxiety levels of the children.35 In another study, correlations between preoperative anxiety levels of the children, and their mothers were found.36 In a study performed by Fortier et al. an inverse correlation was detected between educational level of the family, and the anxiety level of their child.33 In a separate study, a similar correlation was detected between socioeconomic level of the family, and anxiety level of the child.36 However in our evaluation process, anxiety sensitivity index scores of the children were analyzed separately based on the state of family togetherness, income levels of the families, and presence of a psychiatric disease in one or both of the parents, but any statistically significant difference was not detected between subgroups. At this point, we found the timing of the preoperative preparation, required amount of information, and its timing were directly associated with the age and developmental level of the child. Besides this preoperative preparation should last as long as all the questions of the child are answered. However, it should not be too long to create unnecessary worries in the mind of the child.22,30

According to the results of an American epidemiological study, it was detected that 10.5% of the preschool children had a mood disorder like anxiety disorder or depression and 2.1% fit the diagnostic criteria of depressive disorders.37 In preschool children depression manifests itself with irritable affect lasting longer than 2 weeks. Contrary to those seen in adolescents, or adults affective disorders in children are rarely long lasting, and uninterrupted. Since lack of desire for playing with toys, difficulties in arriving a decision, and lack of self-confidence can be early signs of depression, play behaviors of the child should be watched out.38 Subclinical signs, frequent weeping episodes, and nervousness may aid in the diagnosis of depression. During preschool period, clinically identified or subclinical depression combined with anxiety disorder effecting daily life of a child is more worrisome.39 In our study we used updated, and objective scale in the diagnosis, and follow-up of the depression advocated by the literature findings. When we evaluated the outcomes, our overall cut-off value for the depression scale was not 15 points. Irrespective of the subgroups, mean pre-, and post-operative values were 9.03±4.5, and 7.93±3.89 pts (0.001**) respectively. However, mean preoperative depression scale score was statistically significantly higher than corresponding mean postoperative score (P: 0.001; P<0.01). To investigate this significant increase in preoperative depression scale scores, the children were re-evaluated in subgroups based on their social environments, and family structure. In addition to some socio-demographic data as age, and gender of the children, socioeconomic state is also very important. Recently, a socioeconomic gradient has been defined in childhood depression observed in the USA, and Europe. In this study with similar outcomes in adults, and children, depression was more frequently encountered among people with lower socioeconomic income level.40,41 Also in our study, a statistically significant difference was found between pre-, and post-operative depression scale scores of the children of the families with different income levels (P: 0.001; P<0.01). As a result of pairwise comparisons aiming to detect the source of difference, depression scale scores of the children of the families with lower income levels were statistically significantly higher than those belonging to the families with moderate (P: 0.001), and good (P: 0.001) income levels (P<0.01).

As a general information on mental, and psychological health state, presence of a family member with a mental disease is an independent risk factor.42–46 A certain psychopathological condition of the mother can directly or indirectly effect the development of the child.47,48 In a study, health-related quality of life scale (HRQL SF-36) scores of the parents were found to be correlated with those of their children.49 As is known, in the children of the depressive mothers cognitive, and behavioral problems (especially internalization) are more frequently seen.50 Also in our study, when compared with the children of healthy parents, in children whose parents have mental disorders pre, and post-operative depression scale scores were statistically significantly higher which further supports literature findings. On the other hand, family integrity and interrelationship between parents are very important for the psychological stability, and type of the reaction of the children when exposed to trauma. Mc Carthy et al. detected direct correlations between unhealthy family setting, presence of only one parent, lack of health-related social security, and life guality of the children.51 At this point, also in our study, when compared with children living with their parents, pre, and post-operative depression scale scores were found to be statistically significantly higher in children of divorced parents (P: 0.001; P<0.01).

In conclusion, before circumcision, in all children to be circumcised tendency to depression, and increase in anxiety were observed irrespective of the presence of subgroups. Following a detailed examination low-income level of the family, disrupted family togetherness, presence of a previous application history of psychiatry outpatient clinic in a parent may be said to increase predisposition to pre, and post-operative depression. However, none of these factors have an independent effect on pre, and post-operative levels of anxiety. At this stage the main factor determining the level of anxiety is the procedure of circumcision itself. However, naturally, larger scale and detailed investigations should be conducted on this issue.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestNo conflict was declared by the authors.