Dermatologic emergencies represent about 8–20% of the diseases seen in the Emergency Department of hospitals. It is often a challenge for primary care physicians to differentiate mundane skin ailments from more serious, life threatening conditions that require immediate intervention. In this review we included the following conditions: Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrosis, pemphigus vulgaris, toxic shock syndrome, fasciitis necrotising, angioedema/urticaria, meningococcemia, Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Las enfermedades dermatológicas representan del 8% al 20% de la consulta en el Servicio de Urgencias de los hospitales. Para el médico de primer contacto constituye un reto el diferenciar enfermedades leves de aquellas que ponen en peligro la vida y requieren intervención inmediata. De estas existen múltiples que pueden ser potencialmente fatales y otras que requieren ser evaluadas por el especialista. En esta revisión se incluyen las siguientes enfermedades: Síndrome de Stevens-Johnson (SSJ)/necrolisis epidérmica tóxica (NET), pénfigo vulgar (PV), síndrome de choque tóxico (SST), fascitis necrotizante (FN), angioedema/urticaria, meningococcemia, enfermedad de Lyme y Fiebre Macular de las Montañas Rocosas (FMMC).

Between 8% and 20% of patients seen in hospital emergency departments present with dermatological diseases.1,2 Differentiating between mild and life-threatening conditions that required immediate treatment can be challenging for doctors in charge of the preliminary assessment of the patient.2 Many dermatological disease can be fatal and must be evaluated by a dermatologist, intensivist, surgeon, or other specialist.3 In this review, we will focus on the following diseases: Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS)/Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), pemphigus vulgaris (PV), toxic shock syndrome (TSS), necrotising fasciitis (NF), angiooedema/urticaria, meningococcaemia, Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF). Some of these entities require aggressive hospital treatment and must be diagnosed immediately. Others should be referred to a specialist for watchful waiting to prevent potentially severe or incapacitating complications.

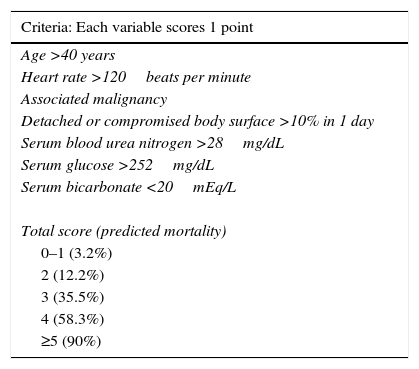

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN)These are part of a spectrum of life-threatening, drug-induced mucocutaneous diseases. The drugs most frequently involved are allopurinol, aniconvulsants such as phenytoin and carbamazepine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, sulphonamides and beta-lactams.3 Incidence is estimated at between 0.4% and 7% per million inhabitants, irrespective of age group or sex. SJS/TEN is characterised by prodromal symptoms such as general malaise, rhinitis, odynophagia, conjuctivitis, myalgia and arthralgia, which can last up to 2 weeks. During this time, a macular rash with or without atypical target lesions appears, usually in truncal areas, and then extends to the extremities. Bullae also form, sometimes accompanied by denuded areas with a positive Nikolsky's sign (Toxic epidermal necrolysis).3–6 (Figs. 1 and 2). Mucous membrane involvement is found in 70–100% of cases, with inflammation, pain and severe ulceration that can progress to involve the oesophageal and tracheal mucosa, thus increasing the risk of respiratory failure.3,5 Nearly all patients have ocular and genital involvement. TEN is believed to be severe form of SJS, where severity is measured by the extent of body surface area (BSA) involvement. In SJS, <10% of total BSA is involved, while in TEN this increases to >30%. Between 10% and 30% of cases are considered to involve SJS/NET overlap.3 NET is characterised by ulceration of the skin, necrosis and severe systemic alterations affecting the lungs, the cardiovascular and gastrointestinal systems, the kidneys and blood. Patients can present with anaemia, leukopaenia, hepatitis, severe abdominal pain, hypoalbuminaemia, hyponatraemia, encephalopathy and myocarditis.5 Diagnosis is based on clinical and histological findings. The main skin findings include erythema, erythematous or violaceous spots and morbilliform or atypical target lesions, which progress to bullae formation, epidermal detachment and even necrosis. Patients report a recent history of constitutional symptoms such as fever, general malaise and anorexia. Mucosal involvement is found in nearly all cases. Histology findings include full thickness epidermal necrosis, separation at the dermoepidermal junction, CD4+ T lymphocyte infiltrates in the dermis and CD8+ T lymphocyte infiltrates in the epidermis. Complications include hypotension, kidney failure, corneal ulcers, anterior uveitis, erosive vulvovaginitis or balanitis, respiratory failure, seizures and coma. The most common sequelae are ocular scars and blindness.4 The mortality rate ranged from 25% to 30%, and can be due to a number of causes, the most common being sepsis. The SCORTEN (SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrosis) (Table 1) scale was developed to assess the severity of the disease and predict a fatal outcome in patients with acute TEN. The scale consists of 7 variables, each scoring 1 point: (1) age >40 years; (2) heart rate >120bpm; (3) associated malignancy; (4) Detached or compromised body surface >10%; (5) serum blood urea nitrogen >28mg/dL; (6) serum glucose >252mg/dL; and (7) serum bicarbonate <20mEq/L. Risk of mortality increases by 3.2% in patients with a score of 0–1 points, by 35.3% in patients scoring 3 points, and up to 90% in patients with a score of ≥5.7 Supportive strategies include identifying and discontinuing administration of the causative drug, admission to a burn unit or intensive care unit, if necessary, administration of intravenous liquids, maintaining electrolyte and temperature homeostasis, and ophthalmologic assessment in the case of occular involvement. Skin lesions should be treated with appropriate dressing; antihistamines and steroids are given for pruritus, and antimicrobial therapy will be rendered in cases of superinfection due to skin-barrier breakdown. Additional therapy consists of ocular lubrication, ophthalmic cyclosporine, and antiseptics for oral hygiene.2 There is insufficient evidence in the literature to recommend adjuvant systemic therapy such as systemic steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, α tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNF-α) and N-acetylcysteine in NET, and these must be used at the discretion of the attending physician.7

Severity of illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis.

| Criteria: Each variable scores 1 point |

|---|

| Age >40 years |

| Heart rate >120beats per minute |

| Associated malignancy |

| Detached or compromised body surface >10% in 1 day |

| Serum blood urea nitrogen >28mg/dL |

| Serum glucose >252mg/dL |

| Serum bicarbonate <20mEq/L |

| Total score (predicted mortality) |

| 0–1 (3.2%) |

| 2 (12.2%) |

| 3 (35.5%) |

| 4 (58.3%) |

| ≥5 (90%) |

Data from Swartz et al.

PV continues to be associated with significant morbidity. Annual incidence of the disease is 0.42 per 100,000 inhabitants, and is most common in people between the ages of 40 and 60 years. PV is a blistering skin disease in which between 50% and 70% of patients present with painful oral lesions. The primary eruption consists of flaccid blisters that easily rupture leaving painful, superficial erosions on the oral epithelium, lips and palate. This can be followed by flaccid blisters on seemingly healthy skin, with a positive Nikolsky's sign, which rapidly progress to painful erosions, predominantly on the scalp, truncal area, and often on the face and neck (Figs. 3 and 4). The areas of erosion can be large, painful, and prone to bleeding. Other areas of involvement include the oesophageal, laryngeal, nasopharyngeal, vaginal and rectal mucosa. Diagnosis is based on clinical signs and direct immunofluorescence assay.3,8 Histopathology findings include suprabasilar bullae with predominantly neutrophilic and eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence shows immunoglobulin G (IgG) and complement (C3) deposition on cell surfaces, giving the characteristic “honeycomb” pattern”.8,9 Patients with extensive lesions should be admitted to a specialised dermatology ward, and multidisciplinary management is sometimes required. Treatment consists of topical steroids for early oral lesions and systemic steroids for extended disease. These can be combined with adjuvant immunosuppressive therapy from the outset, particularly in patients at high risk due to steroid therapy. They can also be combined with first-line drugs such as azathioprine (1–3mg/kg/day) or mycophenolate mofetil (2g/day) or mycophenolic acid (144mg/day).10–12 Supportive therapy consists of antiseptic dressings, analgesics, nutritional management and evaluation by a gastroenterologist. PV can cause permanent sequelae, not only from skin and mucosal lesions, but also from the side effects of treatment. Poor prognosis factors in patients with PV include: onset before 40 years of age, ethnic origin (Sephardic Jews), mucosal involvement, and poor response to treatment.13 Evolution is chronic, and without prompt treatment mortality rates can be as high as 50%, usually due to secondary sepsis. Mortality fell to 10% after the introduction of systemic steroids.3

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS)Toxic shock syndrome is an acute, multi-system, toxin-mediated illness, often resulting in shock and multi-organ failure early in its course. It represents the most fulminant expression of a spectrum of diseases caused by toxin-producing strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus [GAS]). It has an incidence of 1–5 per 100,000 inhabitants. It can result from primary S. aureus infection in women who use tampons during their menstrual period, or in patients with infected surgical wounds. When it is caused by S. pyogenes it is secondary to soft-tissue infections, with a mortality rate of 30%. TSS is found at the extremes of age, and mortality is greater among patients with comorbidities, patients recovering from varicella infection, and those taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.13 The toxins released by these bacteria trigger massive cytokine secretion by T lymphocytes, leading to hypotension and multiorgan failure. TSS secondary to S. aureus infection presents after a 2–3-day prodromal illness consisting of fever, chills, nausea and abdominal pain. This is followed by the appearance of a generalised, nonpruritic maculopapular or petechial rash. Desquamation is a characteristic late feature. Signs appear initially in truncal areas and extend outwards to affect the soles and palms. Multiorgan failure consists of arrhythmia, kidney and liver failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation and acute respiratory distress syndrome .2 Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome is usually triggered by soft tissue infection such as necrotising fasciitis, cellulitis, and myositis. Patients present with a prodromal illness involving fever, odynophagia, enlarged lymph glands and abdominal pain. The initial lesion not be evident, and can present as a blunt trauma, haematoma, muscle strain or joint effusion. Examination may reveal rash, haemorrhagic bullae, skin sloughing, and oedema. Patients rapidly progress to hypotension and organ failure. Diagnosis of TSS is based on both clinical signs and culture of body fluids. However, the presence or absence of bacteria will not affect prognosis. Mortality associated with streptococcal TSS is much higher than with staphylococcal TSS, and can be as high as 80% in association with myositiss.13 Aggressive supportive management is required to treat hypotension and potential multi-organ failure.2 Antibiotic treatment with β-lactams and lincosamides is recommended while awaiting the results of specimen culture.13

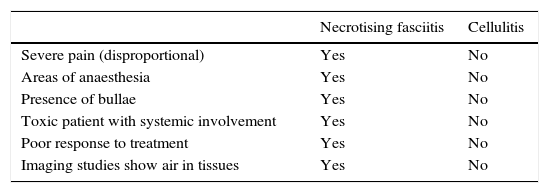

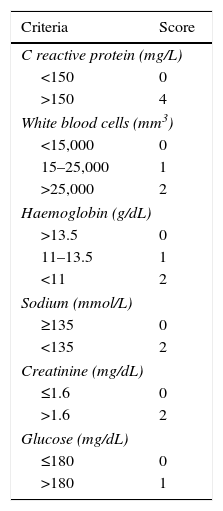

Necrotising fasciitisNecrotising fasciitis (NF) is a potentially fatal soft-tissue infection characterised by extensive necrosis of the superficial fascia. Onset is insidious, and the disease progresses rapidly. NF can arise after a skin lesion or through haematogenous dissemination. Around 50% of cases involve young adults. Infection can be polymicrobial or caused by a single pathogen, most frequently Streptoccocus pyogenes. Polymicrobial NF is typically caused by a mixture of anaerobic and facultative organisms that act in synergy to cause initial symptoms that can be mistaken for cellulitis. As the disease progresses, infectious organisms proliferate and spread from the subcutaneous tissue along the superficial and deep fascial planes. Enzymes and bacterial toxins are pivotal to the infection, as exotoxins bind the T-cell receptors triggering excessive cytokine secretion, which is a factor in organ failure and septic shock syndrome.14 Preliminary skin findings in streptococcal NF are diffuse oedema of the affected area, severe pain, fever and chills. This is followed by the appearance of haemorrhagic bullae; as infection progresses painless ulcers develop. If not treated promptly, the patient will develop eschar, vascular occlusion, ischaemia and tissue necrosis (Figs. 5 and 6). Findings of hypotension, tachycardia, pain disproportionate to the obvious lesion and local crepitus are signs and symptoms that should raise suspicion of NF. Rapid disease progression and poor response to treatment in a patient diagnosed with cellulitis, with tachycardia and altered mental state also suggest NF. It is important to rule out urticaria, as both entities are clinically similar (Table 2).2,13,15 Diagnostic likelihood can be established on the basis of the Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotising Fasciitis (LRINEC). In this system, a score of ≥6 raises suspicion of NF, while a score of ≥ is highly predictive of the disease (Table 3).16 Plain radiography can reveal the presence of gas in soft tissue. Computed tomography is more sensitive in the detection of subcutaneous gas, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can define the extension of the disease and is also useful in guiding emergency surgical debridement. The sensitivity of MRI, however, is marred by its lack of specificity.14 Prompt diagnosis, aggressive management of the infection and surgical debridement of necrotic tissue are essential for effective treatment of NF. Antibiotics suitable for streptococcal infection should be administered. Wide spectrum antibiotics should be used when the causal agent cannot be identified. Intravenous immunoglobin can be a beneficial concomitant treatment to neutralise superantigens and reduce TNF-α and IL-6 levels.2

Differential diagnosis between necrotising fasciitis and cellulitis.

| Necrotising fasciitis | Cellulitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Severe pain (disproportional) | Yes | No |

| Areas of anaesthesia | Yes | No |

| Presence of bullae | Yes | No |

| Toxic patient with systemic involvement | Yes | No |

| Poor response to treatment | Yes | No |

| Imaging studies show air in tissues | Yes | No |

Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotising Fasciitis (LRINEC).

| Criteria | Score |

|---|---|

| C reactive protein (mg/L) | |

| <150 | 0 |

| >150 | 4 |

| White blood cells (mm3) | |

| <15,000 | 0 |

| 15–25,000 | 1 |

| >25,000 | 2 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | |

| >13.5 | 0 |

| 11–13.5 | 1 |

| <11 | 2 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | |

| ≥135 | 0 |

| <135 | 2 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | |

| ≤1.6 | 0 |

| >1.6 | 2 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | |

| ≤180 | 0 |

| >180 | 1 |

Drug hypersensitivity reactions are difficult to predict and can be life-threatening. This type of reaction is characterised by the appearance of symptoms within 1h following administration of the drug. Patients usually present with urticaria, angiooedema, rhinitis, bronchospasm, anaphylaxis or anaphylactic shock, mainly mediated by immunoglobulin E (IgE). Acute urticaria and angiooedema are usual self-limiting. However, mucocutaneous airway inflammation can be life-threatening in itself, or can be a contributing factor in anaphylactic shock. Urticaria is characterised by pruritic rash that can appear on any part of the body. These manifestations last only a few hours while new lesion appears in other areas.17 Angiooedema is characterised by well-circumscribed areas of oedema caused by increased vascular permeability. It most frequently involves the skin and the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts. Patients typically present subcutaneous oedema, generally on the face, extremities and genitals. Unlike a rash, which is pruritic, the oedema is accompanied by burning pain and sensation of pressure at the site of the swelling. In contrast to urticaria, angiooedema can persist for several days.2,17 Urticaria can be associated with angioedema in 50% of cases. Although often idiopathic, angioedema can be induced by medications, allergens, or physical agents.2 Typically, 10–25% of cases are due to angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitor therapy, which occurs in 1–2 per 1000 new users. In these cases, it is not associated with urticaria, and the angiooedema is asymmetrical and lasts between 24 and 48h17 Penicillins, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and radiographic contrast media are other important triggers. Angioedema can occur as a result of C1 (INHC1) esterase inhibitor deficiency. Two rare but well-described categories exist: hereditary angioedema, which is transmitted in autosomal-dominant fashion; and acquired angioedema, which can be associated with autoimmune disorders and B-cell lymphoproliferative malignant disease.2,18 The skin is involved in 90% of cases of anaphylactic shock (urticaria and/or angiooedema). Other organs involved include the upper respiratory tract (inflammation of the tongue and larynx), lower respiratory tract (dyspnoea, wheezing, hypoxaemia), gastrointestinal tract (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal pain) and the cardiovascular system (dizziness, hypotension and syncope) in around 30% of patients.17 Treatment is largely supportive. Airway patency must be ensured. Cool, moist compresses and antihistamines can be used to control local burning. Referral to an allergy specialist for appropriate investigations should be considered.

MeningococcaemiaMeningococcaemia is a leading cause of meningitis in the paediatric population. It is caused by Neisseria meningitidis, and incidence is estimated at 1.1 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. It affects children and adolescents, with incidence peaking in infants aged 6–12 months. The classic presentation of meningococcaemia is maculopapular or petechial rash and fever, chills, malaise and disorientation.2,3 Rash is a pathognomonic sign of the disease, starting with tender skin followed by erythema, which is hard to distinguish from a viral rash. These signs are followed by petechiae on the wrists, ankles and axillae, which spreads to the head, palms and soles. Within a few hours, these progress to form a purpuric rash, followed by thrombolysis with perivascular bleeding. The disease rapidly progresses to septic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, shock and death.3 Meningococcaemia should be suspected in all patients, particularly children, presenting with petechial rash and fever, and blood, cerebrospinal fluid (if not contraindicated), needle aspiration and skin biopsy should be draw for culture to confirm a bacterial pathogenesis.20 Besides supportive management, therapy with a third-generation cephalosporin or intravenous penicillin G2 therapy should be started. Cefotaxime (80mg/kg) or ceftriaxone (80mg/kg) are the treatments of choice for initial management of patients in shock with a clinical diagnosis of meningococcemia. The foregoing therapies can be complemented with systemic dexamethasone to reduce brain damage, although it is contraindicated in meningococcal septic shock without meningitis19 Chloramphenicol can be used in patients with penicillin allergy.2 Patients with persistent shock or signs of raised intracranial pressure should be transferred to an intensive care unit.20

Lyme diseaseLyme disease is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted to humans by 2 species of tick, Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus after passing through a host reservoir, such as deer or mice.3 The disease progresses in 3 stages. Stage 1 (localised) appears 7–10 days after infection and is characterised by erythema migrans (EM) at the site of infection. Patients develop local lymphadenopathy, and around 60% present constitutional symptoms, such as fever, myalgia, arthralgia, malaise, headache and fatigue. In stage 2, the disease spreads to the central nervous (CNS), musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular systems. Dissemination occurs within days or up to months after the initial infection. Borrelial lymphocytoma, which is caused by Borrelia afzelii and is endemic to Europe and Asia, is a cutaneous manifestation of the disease in which patients present multiple EM plaques. Stage 3 is characterised by encephalopathy and chronic arthritis. Skin manifestations are rare at this stage. Around 50% of adults and 90% of children present EM, which is characterised by an erythematous macule at the site of entry which spreads to form a circular macule measuring between 5 and 50cm in diameter (mean 13cm). As it disseminates, the macule takes on the typical bull's eye pattern.22,23 The presence of multiple EM lesions, which can occur simultaneously or sequentially, is typical of stage 2 of the disease. Systemic involvement can occur even in the absence of obvious lesions. When multiple lesions occur, they usually take the form of small, ring-shaped rashes. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA) is a chronic manifestation that can appear months or even years after infection. It manifests as erythematous plaques on the arms and legs, which progress to form atrophic, hyperpigmented lesions. The disease is associated with neuropathy in 60% of cases, mainly allodynia.21 Early diagnosis is essential to prevent systemic involvement. The need for diagnostic tests in areas where Lyme disease is not endemic is controversial. In asymptomatic patients presenting with tick bite, watchful waiting for 30 days is the best approach.22,24 Stage 1 treatment consists of a 3-week course of 100mg doxycycline every 12h.22,25 Intravenous antibiotic therapy is needed in advanced stages with neurological complications, atrioventricular block and meningitis. Although it does not meet the criteria for a medical emergency, early diagnosis of Lyme disease is essential to prevent complications.3

Rocky Mountain spotted feverRocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a potentially life-threatening disease that is usually transmitted to humans through tick bites carrying the bacterium Rickettsia rickettsii.2 Cases of RMSF have been reported in the north and south of Mexico.26 It is associated with a mortality of 3–7% among treated patients and 30–70% among those not treated promptly or adequately. In about 60% of cases, patients present with a triad of fever, headache and rash following a tick bite. The purpuric macules and papules typical of this condition appear within the first 2 weeks on the wrists and ankles. They rapidly spread to the palms and soles and eventually to the trunk and face. Multiorgan involvement may lead to a variety of symptoms. Complications of RMSF include peripheral oedema due to hepatic failure and hypoalbuminemia, myocarditis and cardiogenic shock, acute kidney failure, altered mental state, seizures or coma, meningismus and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Besides symptomatic support, appropriate treatment with doxycycline, the antibiotic drug of choice, should be initiated immediately and continued for 3 after resolution of fever and clinical improvement.27 The tick should be removed if embedded in the skin at the time of presentation.2

ConclusionsMany dermatological diseases are potentially life-threatening, and it is imperative that emergency physicians are able to differentiate between mild conditions and life-threatening diseases that require immediate intervention. In this review, we have described the principle dermatologic diseases that can be potentially fatal. However, there are many more, less common diseases that can be classified as dermatologic emergencies, such as loxoscelism, mucormycosis, cutaneous amebiasis, and so on, in which input from the dermatologist is a key element in diagnostic suspicion.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.