Battered child syndrome is any act of physical, sexual or psychological aggression, negligence or intentional neglect against a minor.

ObjectiveTo estimate the frequency and characteristics of battered child syndrome in patients on the Paediatric Burns Unit of the Health Services of the State of Puebla.

Materials and methodsIn a 1 year and 10 month period, 313 patients under 18 years of age admitted to the Paediatric Burns Unit of the Health Services of the State of Puebla with a diagnosis of burns secondary to battered child syndrome were evaluated and a questionnaire to determine the possibility of child abuse was administered.

Results13 patients met criteria for suspected abuse; 9 were female and 4 were male. One was an infant, 4 were preschool-age children, 4 were school-age children and 4 were adolescents. The form of abuse was negligence and/or neglect in 62% of cases, physical abuse in 15% of cases, sexual abuse in 15% of cases and psychological abuse in 8% of cases.

ConclusionsHaving knowledge of and being able to identify battered child syndrome may prevent fatal injuries. It is important to equip healthcare staff on first-contact care units with the knowledge to establish a presumptive diagnosis of child/adolescent abuse. Only through proper investigation of social events may just solutions be sought and implemented.

El síndrome del niño maltratado es toda agresión u omisión física, sexual, psicológica o negligencia intencional contra una persona menor de edad.

ObjetivoEstimar la frecuencia y características del síndrome del niño maltratado en pacientes de la Unidad Pediátrica de Quemados de los Servicios de Salud del Estado de Puebla.

Material y MétodosEn un periodo de 1 año y 10 meses se evaluaron 313 pacientes menores de 18 años que ingresaron con diagnóstico de quemadura secundaria a síndrome del niño maltratado a la Unidad Pediátrica de Quemados de los Servicios de Salud del Estado de Puebla y se aplicó un cuestionario que permitió establecer la posibilidad de maltrato infantil.

Resultados13 pacientes cumplieron con criterios para la sospecha de maltrato, 9 mujeres y 4 hombres. Un lactante, 4 preescolares, 4 escolares y 4 adolescentes. La forma de maltrato en 62% fue negligencia y/o descuido, 15% físico, sexual 15% y psicológico 8%.

ConclusionesEl conocimiento e identificación del síndrome del niño maltratado puede prevenir lesiones fatales. Es importante capacitar al personal de salud de las unidades de atención de primer contacto con el conocimiento para establecer el diagnóstico presuntivo de maltrato infanto-juvenil. Sólo la adecuada investigación de los hechos sociales permitirá buscar y establecer las soluciones justas.

Battered child syndrome (BCS) is defined as “any act of physical, sexual or psychological aggression, negligence or intentional neglect against a minor that affects his or her biopsychosocial integrity and is performed on a regular or occasional basis, at home or away from home, by a person, institution or society”.1

Since 1999, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has considered it to be a worldwide public health problem.2 The WHO has estimated that 40 million children worldwide from 0 to 14 years of age experience some form of abuse and approximately 53,000 children died in 2002 owing to homicide.3

At the Comprehensive Care Clinic for Abused Children of the Mexican National Paediatric Institute (CAINM-INP), 35–40 new cases of abuse are diagnosed and handled each year.3

Three elements are required for the presentation of BCS: an assaulted child who sometimes suffers from psychomotor delay, an adult aggressor and situations in the family environment involving a triggering factor.4

In Mexico, since 1999, institutions such as the Mexican National System for Comprehensive Family Development (DIF) and the Mexican National Institute for Geographical Statistics and Computing (INEGI) have been keeping a registry of reported and detected causes to show that the problem exists and is increasing.5

There are various risk factors involved in BCS: child factors (under 4 years of age, unwanted and having special needs). Parent or caregiver factors (history of abuse, alcohol consumption, drug use and financial difficulties). Relationship factors (family breakdown and violence between other family members) and social and community factors (social and gender inequalities, unemployment and poverty).6 Physical, emotional and behavioural “indicators” in both the child and the aggressor may be used to diagnose abuse in a minor.7

On the Paediatric Burns Unit (PBU) of the Health Services of the State of Puebla, demand for medical care due to accidental burns has a high incidence; however, there is no instrument that distinguishes cases of accidental origin from cases of non-accidental origin, that is to say, cases that may result from child or adolescent abuse.

The objective was to estimate the frequency and characteristics of battered child syndrome in patients on the Paediatric Burns Unit of the Health Services of the State of Puebla.

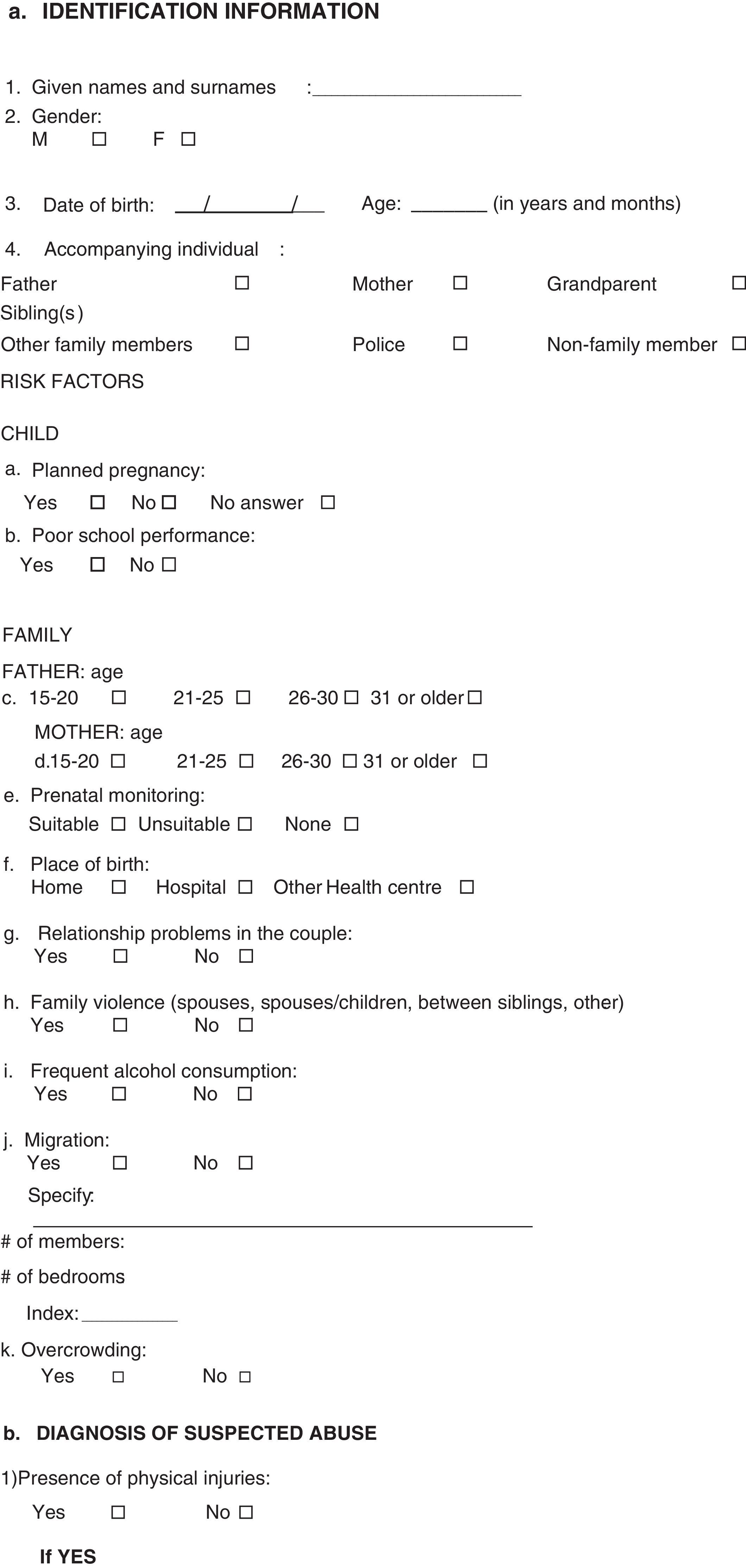

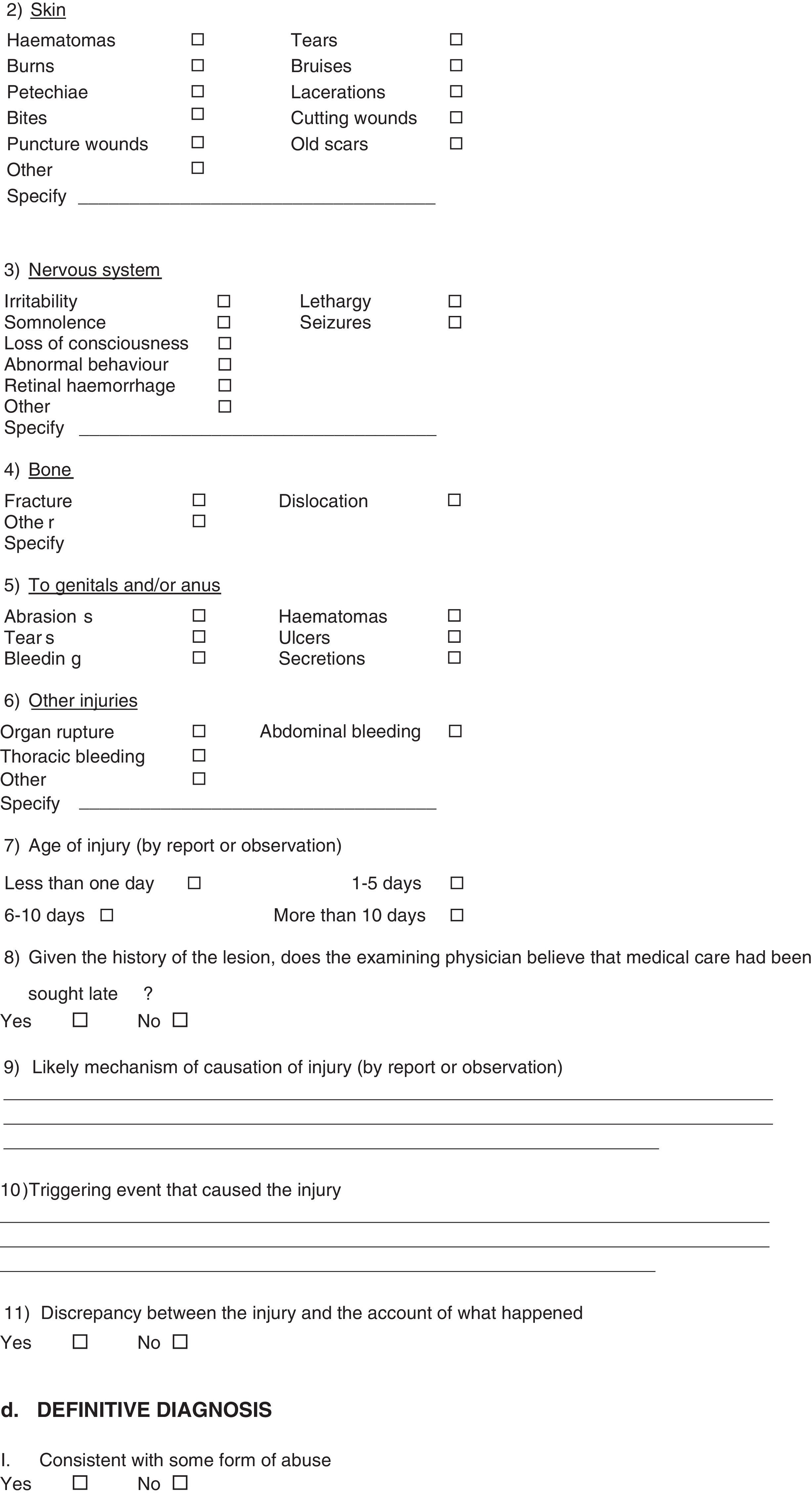

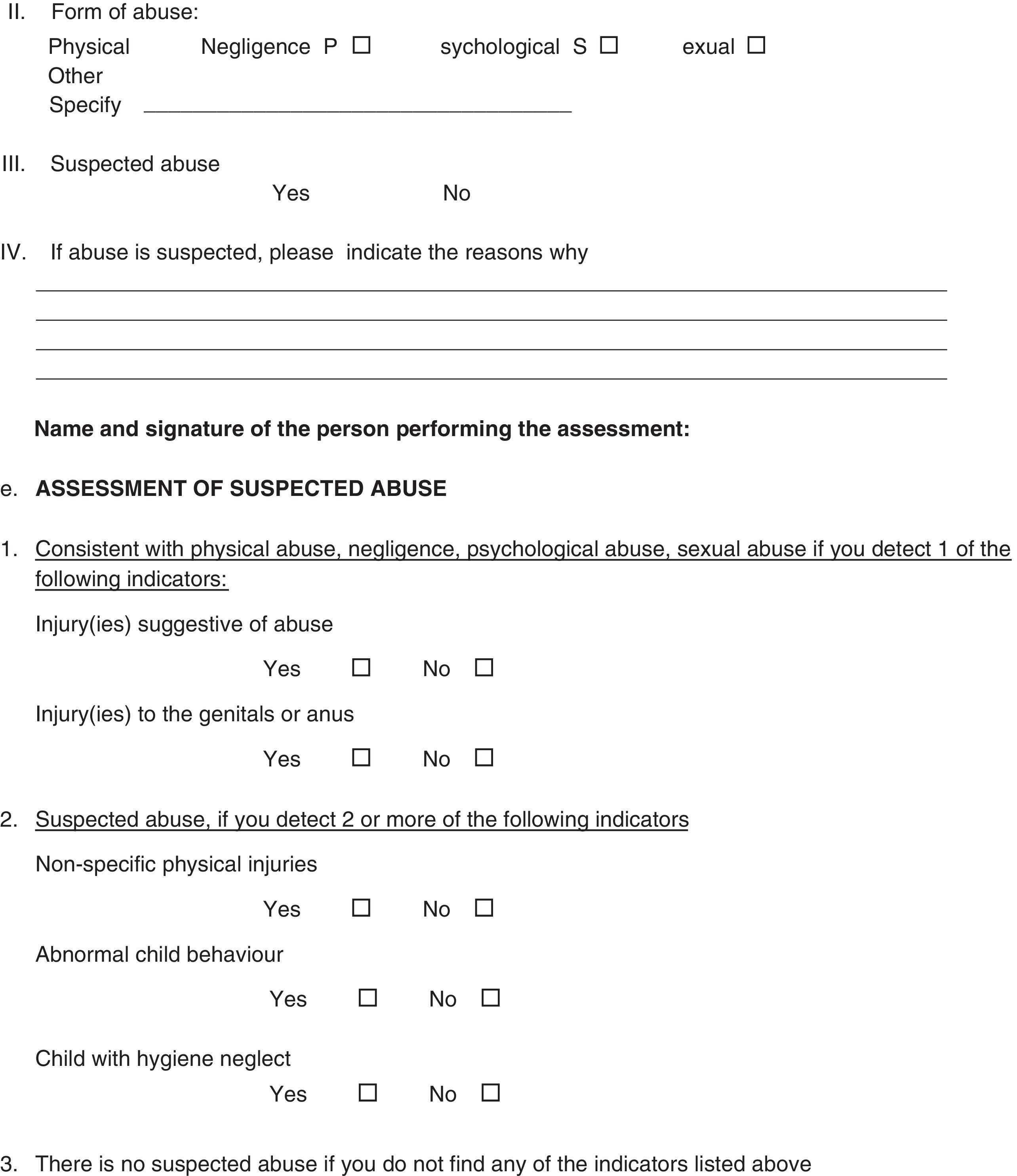

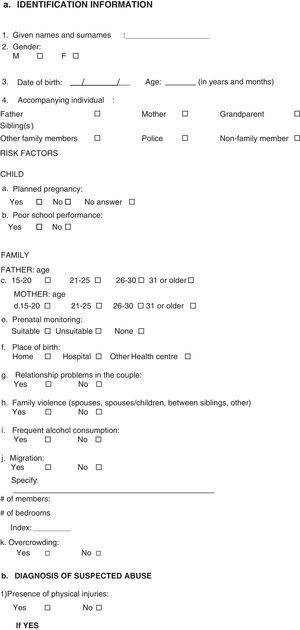

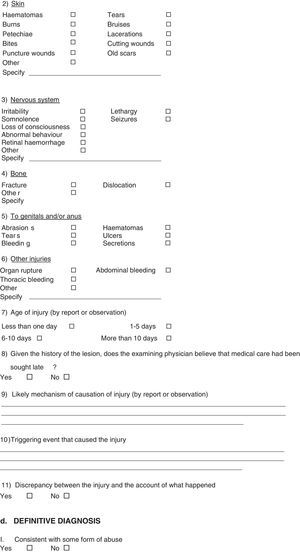

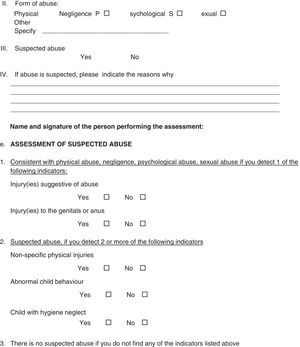

Materials and methodsA longitudinal, descriptive, observational study from January 2013 to December 2014, in patients under 18 years of age admitted to the PBU of the Health Services of the State of Puebla with a diagnosis of burns secondary to battered child syndrome. Patients who were transferred to other medical units or who requested their voluntary discharge were excluded. To establish the possibility of accidental or intentional burns in these patients, a survey with medical and social indicators was conducted to assess child abuse.8 The study was conducted with information obtained from this questionnaire with four headings: identification information, risk factors for the child and for the family; diagnosis of suspected abuse: presence of physical injuries of the skin, nervous system, bones, genitals or anus; assessment of suspected abuse; and definitive diagnosis. Each section assessed different variables (Annex 1). A clinical evaluation was also performed to assess the pattern of injuries and thus determine whether or not they had characteristics of intentional or accidental burns. This survey started to be administered on the patient's arrival at the PBU.

The following findings were looked for in the medical interview:

- –

Inconsistency or changes in the medical record, with little cause/effect relationship

- –

Disconnect between interview information and clinical findings

- –

Inconsistency between the trauma or injury and the child's psychomotor capabilities

- –

Abnormal family reaction to the harm or injury, whether an under-reaction or an over-reaction

- –

Disappearance of symptoms in a family member's absence and reappearance in the family member's presence

- –

Delay in seeking medical attention

- –

Lack of maternal affection

- –

Violent language towards the minor

- –

Multiple injuries in different stages of resolution

- –

Fractures in minors under 2 years of age associated with other consolidated fractures

- –

Symmetrical burns

- –

Sexual abuse

- –

Poor overall appearance in terms of clothing, nutrition and socialisation

- –

Consumption of alcoholic beverages by the people who bring the child in

- –

Other signs that in the clinician's judgement may point to abuse

A total of 313 patients were obtained; 187 of them were male and 126 of them were female. 13 cases were identified as battered child syndrome (BCS); 9 were female (69%) and 4 were male (31%). They were classified by age group as 1 infant, 4 preschool-age children, 4 school-age children and 4 adolescents.

Their risk factors were believed to include the following: young parents — we identified 12 cases in which the mother was ≥18 years of age and 1 case in which the mother was a minor, as opposed to 11 cases in which the father was ≥18 years of age and 2 cases in which the father was a minor; unplanned pregnancy — in 11 cases (85%) the pregnancy was unplanned and in 2 cases (15%) the pregnancy was planned; poor prenatal monitoring — 9 patients (69%) had undergone poor prenatal monitoring and 4 (31%) had undergone suitable prenatal monitoring; and a hospital birth — 11 patients (85%) were born in a hospital setting while 2 patients (15%) were born at home.

The family factors that were investigated included the presence of relationship problems in the couple, which were considered to be a desire or intent to separate. There were relationship problems in 12 cases (92%). With respect to the presence of intrafamily violence, in 10 cases (77%) there was a need for medical and/or psychological care due to inappropriate behaviour on the part of the couple and in 3 cases (23%) there was not such a need; 7 cases (54%) involved alcohol consumption to the point of intoxication and 6 cases (46%) did not. In 11 cases (85%) overcrowding was reported and in 2 cases (25%) it was not.

Of the 13 patients who had physical injuries, 100% had burns, 1 had a fracture, 2 had seizures, 1 had irritability, 1 had somnolence, 1 had lethargy and 1 had an injury to the genitals. At the time of the medical review it was determined that in 4 cases (31%) less than 1 day had elapsed since the injury had occurred, in 6 cases (46%) 1–5 days had elapsed, in 2 cases (15%) 6–10 days had elapsed, and in 1 case (8%) more than 10 days had elapsed since the injury had occurred.

Regarding the medical assessment and the clinical course of the wounds, it was believed that in 11 cases (85%) medical care had been sought late and in 2 cases (15%) medical care had been sought in a timely manner.

Regarding the relationship between the injuries and the account of what had happened, in 11 cases (85%) there were discrepancies and in 2 cases (15%) there were no discrepancies.

The presence of injuries to the genitals and/or anus was examined, and it was found that 1 patient (8%) had abrasions and the other 12 patients (92%) did not have this type of injury.

Of the 13 patients in total, only 2 (15%) stated that they had been assaulted and 11 patients (85%) denied that they had been assaulted.

The patients’ behaviour was studied on their admission in the company of the aggressor: 10 (77%) showed abnormal behaviour while 3 (23%) did not.

In the evaluation on admission it was found that 11 patients (85%) had hygiene neglect while 2 (15%) did not meet this criterion.

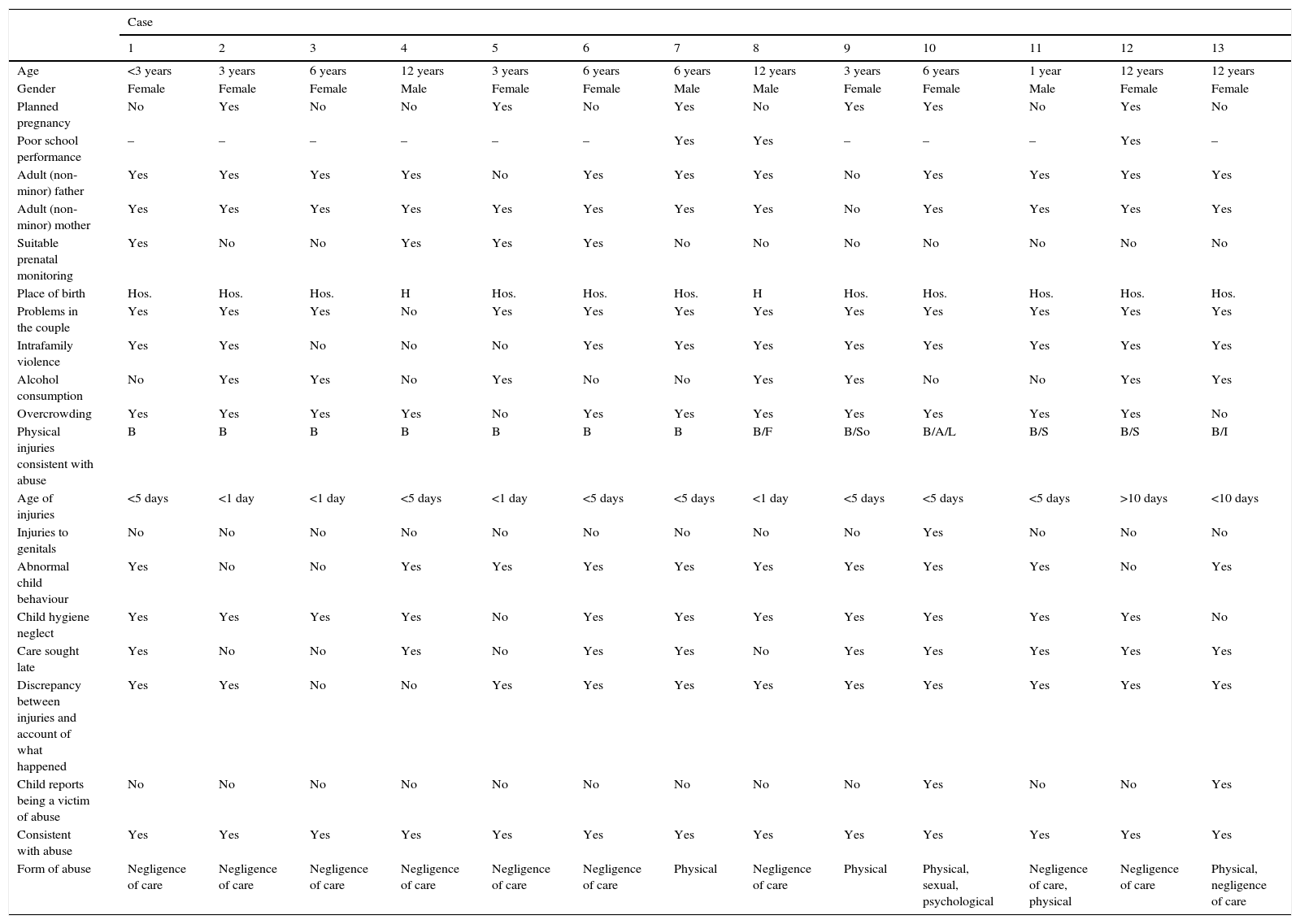

Once battered child syndrome had been diagnosed in the 13 patients, the most common type of abuse was identified. Negligence and/or neglect afflicted 8 patients (62%), 2 patients (15%) had physical abuse in addition to negligence, 2 patients (15%) showed physical abuse exclusively and only 1 patient (8%) had physical, sexual and psychological abuse simultaneously (see Table 1).

Characteristics of each reported case of BCS.

| Case | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

| Age | <3 years | 3 years | 6 years | 12 years | 3 years | 6 years | 6 years | 12 years | 3 years | 6 years | 1 year | 12 years | 12 years |

| Gender | Female | Female | Female | Male | Female | Female | Male | Male | Female | Female | Male | Female | Female |

| Planned pregnancy | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Poor school performance | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes | – |

| Adult (non-minor) father | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adult (non-minor) mother | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Suitable prenatal monitoring | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Place of birth | Hos. | Hos. | Hos. | H | Hos. | Hos. | Hos. | H | Hos. | Hos. | Hos. | Hos. | Hos. |

| Problems in the couple | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Intrafamily violence | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Alcohol consumption | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Overcrowding | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Physical injuries consistent with abuse | B | B | B | B | B | B | B | B/F | B/So | B/A/L | B/S | B/S | B/I |

| Age of injuries | <5 days | <1 day | <1 day | <5 days | <1 day | <5 days | <5 days | <1 day | <5 days | <5 days | <5 days | >10 days | <10 days |

| Injuries to genitals | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Abnormal child behaviour | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Child hygiene neglect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Care sought late | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Discrepancy between injuries and account of what happened | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Child reports being a victim of abuse | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Consistent with abuse | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Form of abuse | Negligence of care | Negligence of care | Negligence of care | Negligence of care | Negligence of care | Negligence of care | Physical | Negligence of care | Physical | Physical, sexual, psychological | Negligence of care, physical | Negligence of care | Physical, negligence of care |

Hos.: hospital, H: home. B: burn, L: lethargy. F: bum/fracture, I: irritability. A: abrasion, S: seizures.

For a long time, children's physical and emotional needs were ignored, and even though knowledge of their requirements for optimal development has improved, abuse has persisted.9 The role of healthcare staff obliges them to report such cases, not only in their professional practice, but also in society, to attempt to resolve the various situations typical of this problem.10 Medical intervention in cases of child abuse consists of: establishing the diagnosis, or the suspected diagnosis, of abuse; starting the necessary treatment; and ensuring that the minor is protected so that he or she is not assaulted again.11 To do this, we require the cooperation of other professionals and specialists.

The immediate family plays a very important role in children who experience abuse. Generally, the families are dysfunctional and there are risk factors such as alcoholism and drug addiction in addition to the parents’ history of being childhood abuse victims. From an economic point of view, they are families marked by poverty and marginalisation where abandonment and rejection are rife.12 In this study, 54% of patients’ parents consumed alcohol to the point of intoxication, 85% of patients had hygiene neglect, some patients experienced overcrowding and a large percentage of patients did not have access to basic education.

When we compared the results of this report with what has been reported in the specialised literature with respect to sociodemographic considerations, we found a particular prevalence in the female gender, as well as in preschool children. However, we found a low incidence in infants, both groups believed to be the most vulnerable to experiencing abuse.13 Unplanned pregnancy, young parents, mothers with major affective disorders, problems related to the couple, intrafamily violence and alcoholism were the main risk factors14–17 revealed in our study, since more than 50% of the population studied had these risk factors. The most commonly found injuries were second-degree superficial and deep burns by scalding. However, it was not possible to compare with other studies conducted since there have been no reports from paediatric burns units. It has been reported that the majority of burns in children occur at home and that the most common places are the kitchen and the bathroom.14 Injuries to the genitals or anus have been the least common type of injury in all reports of abused children. We found 1 case, corresponding to 8% of the population studied. In 85% of cases, medical care was sought late, there was a discrepancy between the injury and the account of the facts, and the child had hygiene neglect corresponding to that reported.3 One noteworthy finding was that 77% (10 cases) exhibited behavioural changes when they were in the company of their aggressor.18 It is important to mention some limitations of the study. The cases reviewed were selected from a PBU in the State of Puebla; therefore, the results do not specifically reflect the number of cases of child abuse in the community, and for this reason its incidence cannot be calculated.

ConclusionsMinors belong to the most vulnerable populations owing to their physical, affective, economic and social dependence on adults. This renders them easy targets for a range of types of abuse. Health institutions represent a window of opportunity for timely prevention and detection of violence and care in response to it.19

Having knowledge of and being able to identify BCS may prevent injuries that are fatal or leave some type of sequelae, many of which may be prevented with simple strategies such as reporting identified cases.

It must be borne in mind that it is not possible to solve any problem without first gaining an in-depth knowledge of it. Only through proper investigation and knowledge of social events may the most just and appropriate solutions be sought and implemented.

There is much work to be done in the comprehensive management of abused children, since the aim is to prevent the recurrence of abuse as well as its potential negative sequelae.

It must be taken into account that when a child arrives at an intensive burns care unit, child abuse due to negligence of care should initially be suspected, by the simple fact of a minor having suffered such a burn. It must be considered that the mechanisms that caused the injuries may have been preventable by the parents or caregivers (boiling water at floor level, candles, hot food, etc.) or intentional depending on the case.

Physicians must be capable of diagnosing or suspecting abuse in all patients in whom any risk factor has been detected, accompanied by physical or psychological signs of abuse. Identification will allow strategies for prevention and monitoring of the condition to be implemented, in an attempt to halt this multifaceted social phenomenon.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingNo funding.

Conflict of interestNo conflict of interest.

No acknowledgements.