Severe alcoholic hepatitis (SAH) presents high early mortality-rate (90 days) and is related to several complications. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact on early mortality-rate of developed complications in patients with SAH, and to evaluate the accuracy of different prognostic scoring systems to predict early mortality.

Subjects and methodsCohort study. Were included 110 patients with SAH. We collected data about development of complications: acute renal failure (ARF), hepatic encephalopathy (HE), variceal bleeding (VB), infections; alcohol intake (g/day) and presence of cirrhosis by ultrasonography (USG). Child-Pugh, Maddrey's modified discriminant function (DF), Model for End stage Liver Disease (MELD); Age, Bilirubin, INR, and Creatinine score (ABIC); Lille score, and Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score (GAHS) were calculated. Primary endpoint was 90-day mortality. To evaluate survival according to the development of complications we performed a Cox regression model. Accuracy of different prognostic scoring systems was evaluated trough ROC curves.

Results90-day mortality-rate was 71 patients (64.5%). 79 patients (71.8%) had evidence of cirrhosis in the USG, 59 (53.6%) developed HE, 54 (49.1%) ARF, 41 (37.3%) VB, and 41 (37.3%) infection. In the Cox-regression model significant association was found between greater risk of mortality and the development of HE (HR 8.0; IC al 95% 3.0 a 21.4; P=0.0001) and presence of cirrhosis in the USG (HR 3.0; 95% CI 1.0 to 8.7; P=0.045). Regard to prognostic scoring systems we found that Lille score ≥ 0.45 was the best predictor of early mortality in patients with SAH (AUROC=0.83; 95% CI 0.75 to 0.91, P<0.0001).

ConclusionsThe development of HE is the main factor associated to early mortality. Coexistence of cirrhosis is a factor that worsen the prognosis. Lille score is the most accurate for predict early mortality.

La hepatitis alcohólica severa (HAS) presenta elevada mortalidad a corto plazo (90 días) y se asocia a diversas complicaciones. El objetivo de este estudio fue valorar el impacto que tienen las complicaciones desarrolladas en pacientes con HAS sobre la mortalidad temprana y evaluar la exactitud de diferentes índices para predecir mortalidad a corto plazo.

Materiales y métodosEstudio de cohorte. Se incluyeron 110 pacientes con diagnóstico de HAS. Se registraron desarrollo de complicaciones: Insuficiencia renal aguda (IRA), encefalopatía hepática (EH), hemorragia variceal (HV), infecciones, consumo de alcohol (g/día) y presencia de cirrosis por ultrasonido (USG). Se calcularon Child-Pugh; función discriminante modificada de Maddrey; Model for End stage Liver Disease (MELD); Age, Bilirubin, INR, and Creatinine score (ABIC); puntuación de Lille, escala de hepatitis alcohólica de Glasgow (GAHS). El desenlace primario fue mortalidad a 90 días. Para evaluar supervivencia en relación al desarrollo de complicaciones se realizó regresión de Cox. La exactitud de los diferentes índices pronósticos se evaluó mediante curvas COR.

ResultadosLa mortalidad a 90 días fue de 71 pacientes (64.5%). 79 pacientes (71.8%) tenían evidencia de cirrosis por USG, 59 (53.6%) desarrollaron EH, 54 (49.1%) IRA, 41 (37.3%) HV, y 41 (37.3%) infección. En el análisis de regresión de Cox se encontró asociación entre riesgo de mortalidad y desarrollo de EH (HR 8.0; IC al 95% 3.0 a 21.4; P=0.0001) y presencia de cirrosis en USG (HR 3.0; IC al 95% 1.0 a 8.7; P=0.045). Respecto a los índices pronósticos el puntaje de Lille ≥ 0.45 fue el mejor predictor de mortalidad temprana en pacientes con HAS (ABC=0.83; IC al 95% 0.75 a 0.91, P<0.0001).

ConclusionesEl desarrollo de EH es el principal factor asociado a mortalidad temprana. La coexistencia de cirrosis es un factor que empeora el pronóstico. El puntaje de Lille es el más exacto para predecir mortalidad temprana.

Severe alcoholic hepatitis (SAH) is a pathological condition associated with a high risk short-term mortality (90 days), without treatment, 50% of patients die within the first two months.1–4 Treatment with corticosteroids or pentoxifylline has demonstrated improvement on survival, nevertheless, immediate mortality remains ranging from 15% to 50% of cases according to severity.5 Several factors, such as, excessive alcohol intake and cirrhosis, age, liver failure, gastrointestinal bleeding, concomitant viral B or C infection and persistent alcohol intake, have been identified as independent poor prognostic markers in patients with chronic liver disease.6 In patients with SAH, the development of complications, such as, hepatic encephalopathy (HE) or hepatorenal syndrome has a negative impact on survival.7

Several scoring systems are available to establish a prognosis in patients with SAH. The clinical utility of the different scoring systems has been compared by several studies with conflicting results.8 Is true that Maddrey's modified discriminant function (DF) is a useful tool to determine need for therapy if it is ≥ 32.9 However, to assess the prognosis of patients with SAH, several studies have demonstrated that the Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, the Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score (GAHS), and the Hepatic Venous Pressure Gradient (HVPG) are better predictors of survival than DF.10–17 The Lille score has shown to identify patients who do not respond to corticosteroids therapy, with an increased risk of death in the next 6 months.18 The Age, Bilirubin, INR, and Creatinine (ABIC) score identify patients with low, intermediate and high risk of death at 90 days and at 1 year.19

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact on early mortality-rate (90 days) of developed complications in patients with SAH, and to evaluate the accuracy of different prognostic scoring systems to predict early mortality.

Subjects and methodsStudy designObservational, prospective, cohort study. We evaluated 121 patients. Were included 110 patients with SAH diagnosis who were attended at Gastroenterology Department from “Hospital General de México” from April 2010 to May 2012. We excluded patients with concomitant comorbidities: chronic hepatitis C (4), chronic hepatitis B (1), diabetes (3), concomitant use of herbal (3).

ProcedureWe collected data about development of complications: acute renal failure (ARF), HE, variceal bleeding (VB), infections; alcohol intake expressed as g/day and presence of cirrhosis in the ultrasonography (USG). Child-Pugh, DF, MELD, ABIC, Lille score, and GAHS were calculated. Primary endpoint was mortality at 90 days.

DefinitionsSevere alcoholic hepatitis (SAH)Was defined according to clinical and biochemical parameters as follows: History of chronic and heavy alcohol intake greater than 80g/day in the last 5 years, with rapid onset of jaundice in the absence of biliary tract obstruction by ultrasound, with painful hepatomegaly and ascites, raised transaminases more than two times above the normal value, aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio greater than 2 times normal value, leukocytosis with predominance of neutrophils, total bilirubin greater than 5mg/dL, DF greater than 32, calculated with the formula [4.6 x(patient prothrombin time (PT) –control PT, in seconds)+ Total bilirubin in mg/dL].7,20

Acute renal failure (ARF)This condition was defined, according to the criteria from the Acute Kidney Injury Network, as the abrupt reduction (48hours) of renal function, characterized by an increase of 0.3mg/dL in the serum creatinine compared with the baseline value. Patients who had a baseline value of serum creatinine greater than 1.5mg/dL at the time of admission were considered ARF cases.21,22

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE)This condition was defined clinically by neuropsychiatric alterations and neuromuscular signs according to the West-Haven criteria.23

Variceal bleeding (VB)This condition was defined by the presence of melena or hematemesis associated with gastroesophageal varices determined by endoscopy.24

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)Was defined according to the guidelines of the American Association for Study of Liver Diseases, as an ascites neutrophil count greater than 250/mm3.25

Other infectionsPneumonia was diagnosed in patients who developed cough with expectoration and consolidation in the chest X-ray. Urinary tract infection was diagnosed in patients having urinary symptoms associated with abnormal urinary examination and urinary cultures, including a bacterial count greater than 100,000 CFU. Patients with diarrhea were evaluated by microscopic fresh stool examination and stool cultures. When patients developed odynophagia or dysphagia, esophageal candidiasis was considered. The diagnosis was confirmed through oral cavity examination and endoscopy with the presence of compatible lesions; brushing for mycological examination was performed in all cases.

Coexistence of cirrhosis by USGThese data was collected from the report of the radiologist according to ultrasonographic findings such as, increased coarsened and heterogeneous echo texture of the liver, surface nodularity, segmental hypertrophy/atrophy including caudate width/right lobe width > 0.65, signs of portal hypertension, including enlarged portal vein > 13mm, enlarged superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and splenic vein > 10mm, loss of respiratory variation in SMV and splenic vein diameter, reversal or to-and-fro portal vein flow, portal vein thrombosis and/or cavernous transformation, portalization of hepatic vein waveform, recanalization and hepatofugal paraumbilical venous flow, portosystemic collaterals.26

Statistical analysisThe distribution of numerical variables were analyzed with Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, asymmetry and kurtosis, in case of non-normal distribution were expressed as median and range, and in case of normal distribution as mean and standard deviation (SD). Qualitative variables were expressed as proportion and percentage. To evaluate survival according to the development of complications we performed a Cox regression model. Accuracy of different prognostic scoring systems was evaluated trough ROC curves. A P value≤0.05 was considered significant. SPSS version 19.0 was employed.

Results103 patients (93.6%) were male. Media of age was 43.3±9.3 year-old. Media of alcohol intake was 342±170g/day. About treatment, 70 patients (63.6%) received prednisone 40mg/day and 40 (36.4%) were treated with pentoxifylline 400mg thrice in day. Mortality rate at 90 days was 71 patients (64.5%). All patients were classified as Child-Pugh C. 79 patients (71.8%) had evidence of cirrhosis in the USG, 59 (53.6%) developed HE, 54 (49.1%) developed ARF, 41 (37.3%) developed VB, 41 (37.3%) developed infection. The reported infections were: 18 patients (16.4%) developed esophageal candidiasis, 10 (9.1%) urinary tract infection, 7 (6.4%) SBP, 4 (3.6%) pneumonia, 2 (1.8%) diarrhea.

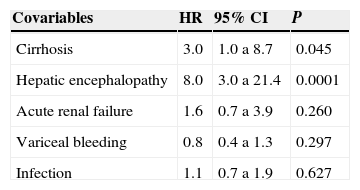

In the Cox-regression model significant association was found between greater risk of mortality and the development of HE (HR 8.0; IC al 95% 3.0 a 21.4; P=0.0001) and presence of cirrhosis in the USG (HR 3.0; 95% CI 1.0 to 8.7; P=0.045). See table 1.

Cox regression model evaluating main determinant clinical factors associated to mortality at 90 days in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.

| Covariables | HR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | 3.0 | 1.0 a 8.7 | 0.045 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 8.0 | 3.0 a 21.4 | 0.0001 |

| Acute renal failure | 1.6 | 0.7 a 3.9 | 0.260 |

| Variceal bleeding | 0.8 | 0.4 a 1.3 | 0.297 |

| Infection | 1.1 | 0.7 a 1.9 | 0.627 |

CI=confidence interval; HR=Hazard ratio.

P≤0.05 was considered significant.

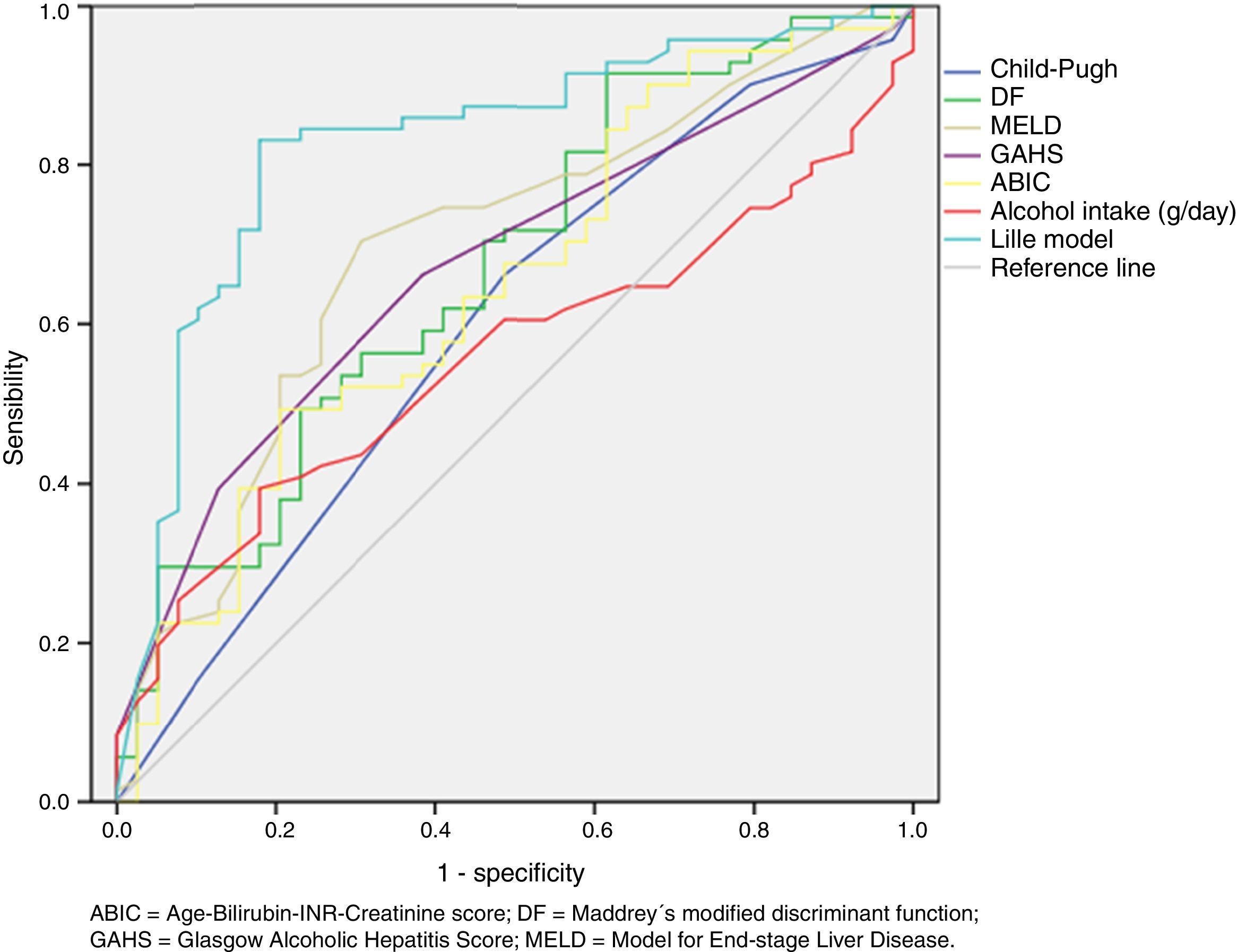

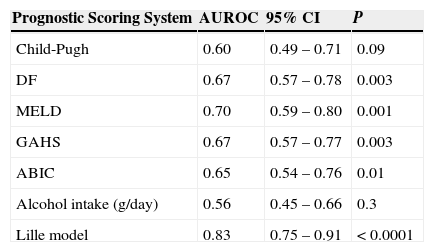

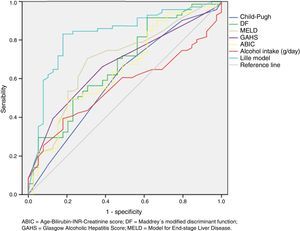

Regard to prognostic scoring systems we found that Lille score ≥ 0.45 was the best predictor of early mortality in patients with SAH (AUROC=0.83; 95% CI 0.75 to 0.91, P<0.0001). See table 2 and figure 1.

Comparision between of the area under de curve of different prognostic scoring systems to predict mortality at 90 days in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.

| Prognostic Scoring System | AUROC | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child-Pugh | 0.60 | 0.49 – 0.71 | 0.09 |

| DF | 0.67 | 0.57 – 0.78 | 0.003 |

| MELD | 0.70 | 0.59 – 0.80 | 0.001 |

| GAHS | 0.67 | 0.57 – 0.77 | 0.003 |

| ABIC | 0.65 | 0.54 – 0.76 | 0.01 |

| Alcohol intake (g/day) | 0.56 | 0.45 – 0.66 | 0.3 |

| Lille model | 0.83 | 0.75 – 0.91 | < 0.0001 |

ABIC=Age-Bilirubin-INR-Creatinine score; AUROC=area under de receiver operating charcteristic curve; CI=confidence interval; DF=Maddrey's modified discriminant function; GAHS=Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score; MELD=Model for End-stage Liver Disease.

P≤0.05 was considered significant.

Area under de receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of different prognostic scoring systems to predict mortality at 90 days in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.

ABIC=Age-Bilirubin-International normalized ratio-Creatinine score; DF=Maddrey's modified discriminant function; GAHS=Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score; MELD=Model for End-stage Liver Disease.

In our cohort most of patients were male (93.6%). Worldwide, men are more likely than women to drink excessively. Excessive drinking is associated with significant increases in short-term risks to health and safety, and the risk increases as the amount of drinking increases.27–31 Patterns of alcohol consumption also is different between men and women, for example, men average about 12.5 binge drinking episodes per person per year, while women average about 2.7 binge drinking episodes per year.28 Proportion of patients who meet criteria for alcohol dependence is greater in men than in women (17% vs. 8%, respectively).32 Men consistently have higher rates of alcohol-related deaths and hospitalizations than women.33,34

In our cohort, the media of age was 43.3±9.3 year-old. In Mexico, cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases represents the second cause of death in economically active population (age ranging from15 to 64 year-old).35

About treatment, 70 patients (63.6%) received prednisone 40mg/day and 40 (36.4%) were treated with pentoxifylline 400mg thrice in day. Actually, corticosteroids are recommended as the first line therapy for severe alcoholic hepatitis, pentoxifylline usually is reserved for those cases with any contraindication for corticosteroids use; such as, gastrointestinal bleeding; active bacterial, viral or fungal infections; or acute renal failure.36 An advantage from the treatment with pentoxifylline, is that has demonstrated protective effect against development of hepatorenal syndrome.37–40 However, there is no evidence about significant difference in survival-rate at 30 days between patients treated with corticosteroids and those treated with pentoxifylline.39,40

Mortality rate at 90 days in our cohort was 64.5%. Alcoholic hepatitis is a distinct clinical syndrome among people with chronic and active alcohol abuse, with a potential for 30 - 40% mortality at 1 month among those with severe disease. Corticosteroids or pentoxifylline are the current pharmacologic treatment options, but they provide only about 50% survival benefit.41

In our study, main clinical risk factor associated with mortality in patients with SAH, were concomitant cirrhosis demonstrated by USG and the development of HE. However, several are the clinical factors associated with poor prognosis and short-term mortality in patients with SAH. Altamirano J, et al,42 found that alcohol intake ≥120g/day was associated with greater mortality-rate in a cohort of Mexican patients. However, when we evaluated the alcohol intake isolated as a prognostic test, we identified that this parameter is not the best for this purpose. Potts JR, et al,43 in a large cohort of English patients, found that the overall mortality was 57.8%, 96.8% of deaths being liver-related and 65.1% occurring after the index hospitalization. Hepatorenal syndrome was the only baseline factor independently associated with short-term mortality (HR 3.78, 95% CI 1.98–7.19, P<0.0001). Zhao JM, et al,44 evaluated factors related to mortality in patients with severe hepatitis for several causes, they found that mortality was higher in patients with cirrhosis compared with non-cirrhotic patients (40% vs. 4.3%, P=0.002). Also, patients without HE had lower mortality than with HE (3.33% vs 46.51%). The mortality of patients with HE Stage III and IV was 72.73%. Finally, the results of multivariate conditional logistic regression analysis indicated that HE, serum creatinine levels were risk factors for death. Recently, Orntoft NW, et al,45 found that most deaths within the first 84 days after admission in patients with alcoholic hepatitis resulted from liver failure (40%), infections (20%), or hepatorenal syndrome (11%). Beyond 84 days, causes of deaths differed between patients with and without cirrhosis; cirrhosis was present in 51% of patients diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis; most patients without cirrhosis died of causes related to alcohol abuse, whereas most patients with cirrhosis (n=675) died of liver failure (34%), infections (16%), or VB (11%).

In our study, infections did not represent a major cause of death in patients with SAH. However, other authors have reported bacterial infections as a main cause of death.46–49 Immune system dysfunction has been reported in patients with SAH. Neutrophils are an essential component of the innate immune response and key players in the pathogenesis of alcoholic hepatitis. Jaeschke H, et al,50 found decreased neutrophil phagocytic capacity correlating with disease severity. Mookerjee RP, et al,51 also demonstrated neutrophil dysfunction in patients with alcoholic hepatitis.52 Regard to infections found in our patients, is noteworthy that the most frequent was esophageal candidiasis, an explanation for this finding could be the potential side-effects of corticosteroids that are numerous, including anti-anabolism, muscle breakdown, immunosuppression, increased susceptibility to infection, and increased risk of GI bleeding.53

Several studies have compared the accuracy to predict mortality-rate of the available prognostic systems, nevertheless, this is the first study that compared the five main scoring systems available to assess the prognosis in alcoholic hepatitis (Lille score, ABIC, MELD, DF, GAHS). This study demonstrated that response to treatment, evaluated trough the Lille score was the best predictor of early mortality in patients with SAH. According to Lille score, patients with SAH are classified as non-responders if Lille score results above 0.45. In the original study, Louvet A, et al,54 found that non-responders have a marked decrease in 6-month survival as compared with responders (25%+/- 3.8% versus 85%+/- 2.5%, P<0.0001). A very important variable in the Lille score is the level of serum bilirubin at 7 days after start treatment with corticosteroids. The decrease in the bilirubin level is a crucial determinant of response to treatment.54 In a study by Bargalló-García A, et al,55 MELD score, urea and bilirubin values one week after admission were independently associated with both in-hospital survival (OR=1.14, 1.012 and 1.1, respectively), and survival at 6 months (OR=1, 15; 1.014 and 1.016, respectively).

In our study MELD was identified as the second best predictor of early mortality in our cohort, this is consistent with results from the study by Bargalló-García A55, who identified the MELD score as the best scoring system, and similar to ABIC when compared with Child-Pugh and GAHS. Other scoring systems, as DF, GASH, and ABIC obtained similar AUROC values in our study.

Is an important limitation of our study, that our patients lack of biopsy, that is the gold standard to confirm the diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis. Furthermore, our diagnosis of concomitant cirrhosis was based on ultrasonographic changes, and is well known that this is not the best method to confirm the presence of cirrhosis. Also, a good proportion of patients in this cohort received treatment with pentoxifylline, and it is well kwon that this drug is a nephro-protective agent against hepatorenal syndrome development in patients with SAH, thus, this fact could explain that in this cohort, ARF did not represent a risk factor for death, but this asseveration was not formally analyzed in our study.

ConclusionsThe development of HE is the main factor associated to early mortality. Coexistence of cirrhosis is a factor that worsen the prognosis in patients with SAH. Lille score is the most accurate for predict early mortality, then, we could infer that response to treatment is a crucial determinant of survival.

Conflict of interestAuthors declare have not conflict of interest.