Violence is a phenomenon involving the interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors. Several studies have developed programs to prevent the occurrence of these behaviors in children, adolescents and adults. When these programs focus on mothers of young children, not only is there an improvement of child cognitive, emotional and social development, but also the whole family benefits from it.

ObjectiveTo assess the effects of the Programa de Entrenamiento Materno Infantil: Enfoque Neuropsicológico (PREMIEN) in maternal parenting style behaviors and its impact on the development of executive functions in preschool children.

MethodsA descriptive, prospective, correlational study was conducted using a convenience sample that included 40 dyads of mothers and their children between 3 and 6 years old. A control group of 43 children whose mothers did not attend the PREMIEN intervention was paired to the PREMIEN sample in order to compare results at post test assessment. The PREMIEN program was implemented and it provides strategies to the mothers so as to promote physical, cognitive and emotional development of their children. A pre and post assessment of children's perception of parental style of his mother and the development of executive functions was performed.

ResultsThere were changes in perception of parenting style by children at post test and with the control group. There was also an increase in their scores on tasks of executive functions at post test and compared to a control group.

ConclusionsEducational interventions that provide mothers with strategies and knowledge regarding the cognitive and emotional development of their preschool children, have an impact on mother–child relationship, promoting interpersonal affective behavior and mother responsiveness to the needs of their children and they also promote the development of self-control and regulation of children, which allow them a functional social adjustment, thus preventing the onset of antisocial behavior.

La violencia es un fenómeno que implican factores biológicos, psicológicos y sociales. Diversos estudios han desarrollado programas para prevenir conductas violentas en niños, adolescentes y adultos. Los resultados muestran que cuando estos programas se enfocan en madres de niños pequeños, mejoran diversos aspectos no sólo del desarrollo del niño, como su desarrollo cognitivo, emocional y social, sino de la familia en general.

ObjetivoEvaluar los efectos del Programa de Entrenamiento Materno Infantil: Enfoque Neuropsicológico (PREMIEN) en las conductas maternas de estilo parental y el impacto en el desarrollo de las funciones ejecutivas de sus hijos en edad preescolar.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio descriptivo, prospectivo y correlacional utilizando una muestra seleccionada por conveniencia de 40 díadas de madres y sus hijos entre 3 y 6 años. Los niños fueron pareados con una muestra control de 43 niños cuyas madres no asistieron al programa para comparar los resultados del post test. Se implementó el programa PREMIEN el cual proporciona estrategias a las madres para favorecer el desarrollo físico, cognitivo y emocional de sus hijos. Se realizó una evaluación pre y post de los niños sobre la percepción del estilo parental de su madre y el desarrollo de funciones ejecutivas.

ResultadosSe encontraron cambios en la percepción del estilo parental de los niños en el post test y en su desempeño en tareas de funciones ejecutivas en el post test comparado con el pre test y un grupo control.

ConclusionesLas intervenciones que proporcionan estrategias y conocimientos del desarrollo cognitivo y emocional a madres de niños preescolares, tienen un impacto en la relación interpersonal madre-hijo promoviendo conductas afectivas y responsivas ante las necesidades de los niños y favorecen su desarrollo de auto control y auto regulación, lo cual que les permitirá mejor ajuste social previniendo la aparición de conductas antisociales.

Violence is a complex phenomenon involving the interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors. Among these factors, executive functions (EF) and dysfunction of the frontal lobes have been given special emphasis. It has been hypothesized that cognitive disorders including impulsivity, poor planning, mental inflexibility, low verbal intelligence, and alterations in attention, predispose subjects to feelings of frustration and anxiety, to difficulties in emotional regulation and finally, to an increased risk of aggressive or violent behavior.1–4

EF is considered a general cognitive and emotional domain that encompasses a variety of functions to guide goal-directed behavior.5–9 Miyake et al.10 identified three separable, but no totally independent constructs of EF. Mental flexibility is considered as the ability to shift set, to alter behavior according to changes in the dimensional relevance of stimuli11; in addition, working memory is defined as the process by which symbolic representations are accessed and held on-line to guide a response.12 Finally, inhibition is the ability to supress a dominant response and execute an alrtenate one instead.13

Developmental research has shown that EF emerge early in development and they develop with important changes between 2 and 5 years old. This age is considered as an important stage in the acquisition of self-regulated behavior, both in cognitive and emotional domains.14 Emotional development and emotion regulation are considered to maintain a bi-directional influence on the development of EF. Self-regulation assumes a consequence of vertical and horizontal integration across levels of biological and social influences (i.e. positive social relationships, productivity, achievement, and a positive sense of self). Early childhood programs with activities aimed to exercising and promoting executive functions can be effective in enhancing self-regulation, school readiness, and school success15 Neural systems underlying social, emotional, and cognitive development undergo a protracted development, thus being especially sensitive to environmental influences16 such as care giving and quality of environmental stimulation during infancy and childhood.17

One of the most important environmental factors during childhood is the mother–child relationship. This relationship can be characterized in terms of parental control and parental responsiveness, which are both referred to, as parenting style.18,19 Evidence that links between negative caregiving and child EF are increasingly manifested during early childhood. Although maternal EF and negative caregiving are related, they provide unique information about the development of child EF.20 It has been suggested that positive parenting during the earliest stages of development is a critical environmental factor that has strong influences on child self-regulation, on his social and academic adjustment and overall, on mental health in typically developing children,21–23 thus allowing children to engage in prosocial behaviors and to prevent appearance of violent behaviors or drug addiction even in risk environments.24 Similarly, composite scores of parental behavior and child attachment were related to child performance on EF tasks entailing strong working memory and cognitive flexibility components.25 Researchers pointed out that educational programs aimed to improve the quality of mother–child relationship may be more efficient in preventing appearance of antisocial behaviors in children.26–29 Indeed, results of these programs have shown substantial benefits in reducing crime indices, in raising earnings, on promoting education and in long term, to benefit both adult and children's mental and physical health. Parenting programs16 may be effective in improving aspects of family life that are likely to be associated with maltreatment,7 such as parental attitudes and parenting skills.30,31

Evidence showed that early intervention may prevent later problems. Programs that reduce behavioral problems and promote positive parenting skills are targeting risk factors for later delinquent behavior and violence, and so, they are likely to prevent them.

In order to develop a program to prevent violent behaviors Mexican populations at risk, the ‘Programa de Entrenamiento Materno Infantil: Enfoque Neuropsicológico’ (or PREMIEN in Spanish)32 was developed. The rationale behind this program is in line with the aforementioned notion that posits that the quality of mother–child interactions during infancy and childhood constitutes an important factor for children functional psychological development. Therefore, the PREMIEN32 was designed to provide information to mothers living in high risk environments that would allow them to become aware of the importance of the interaction with their children, and thus, avoid the onset of violent or addictive behaviors.

This program includes 25 group sessions covered in approximately 6 months.

During these sessions, Ph.D. students of the neuropsychological department led weekly sessions targeted to mothers living in high risk environments, in which a strong emphasis to the importance of their child's physical, social, emotional and cognitive development was given. These sessions included group activities, role playing, stories and discussion on focus points. At the end of each session, mothers were given worksheets to carry out daily ludic activities at home with their children for 15min. The worksheets activities include literacy and numerical skills, motor and conceptual abilities, and social and emotional development. The present study was conducted to evaluate the effects of the Programa de Entrenamiento Materno Infantil: Enfoque Neuropsicológico (PREMIEN),32 developed for Mexican population. As aforementioned the program is targeted to mothers who are expected to gain knowledge and implement affective and behavioral strategies in the interaction with their children. However, the effects are expected to indirectly impact their children; thus, we expect to observe changes in the children perception of their mother's parenting style as well as in improvements of their cognitive development, specifically, in executive functions given their relationship with the onset of violent or aggressive behavior. We hypothesized that children whose mothers attended the program would improve their performance in measures of EF after the intervention.

MethodA pre-experimental, non-random controlled trial study was conducted using a convenience sample that included 40 dyads mother–children. Sample was selected from a Mexico's city suburban area, Nicolás Romero, characterized by poverty and lack of urban services. A control group of 43 children whose mothers did not attend the PREMIEN intervention was paired to the PREMIEN sample in order to compare results at post test assessment. For children, exclusionary criteria included history of head injury, learning disability, developmental delay, or other neurological or psychiatric problems.

ProcedureThe sample of mothers and children was assessed prior to the beginning of the PREMIEN program; mothers were assessed regarding their demographic characteristics. Mothers answered a questionnaire to establish socioeconomic status, parental education and occupational status; they also provided information on relevant issues about the development of their children. Children were assessed using the Neuropsychological Battery for Preschoolers33 and a Parenting Style Scale34 in order to establish their perception of their mothers’ parenting style. Children were tested individually in a quiet location.

PREMIEN program was implemented in 25 weekly sessions (6 months).

After completion of the PREMIEN program the sample of mothers and children completed a post-test evaluation to identify the immediate effects of the program on children development of executive functions and perceived mother's parenting style. Mothers answered a questionnaire regarding all the topics reviewed in the program so as to assure they remember the main ones. Children were assessed with the Neuropsychological Battery for Preschoolers33 and the Parenting Style Scale.34 These instruments were also applied to a control group of children between 3 and 6 years old from the same community whose mothers did not attend the program. This control group was only assessed once due to limitations regarding mother's and their children availability to fulfill a second evaluation. These results were used for comparing PREMIEN group at post test.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics on demographic characteristics. Pre and post test results on executive functions of PREMIEN group were analyzed with a t test for related samples. A t test for independent samples and an effect size analysis were used to compare executive functions results of PREMIEN group and control group at post test. A chi square was used to analyze results on children's perceived parenting style at pre and post test for the PREMIEN group and at post test between PREMIEN and control group.

InstrumentsParenting style scale.34 This scale consists of 20 images of different behaviors children would do. Each item includes four possible answers depicting different parental styles: authoritarian, parents use by high levels of control and demands to the child with low levels of nurturance; democratic, exerts high levels of control of child's behavior, in the context of nurturance and open communication; permissive, characterized by high levels of nurturance and warmth, and low levels of control and demands; and neglectful parents are uninvolved in any of their children's activities or needs, neglecting any structure and responsiveness to them.

Children were asked to point to the image that they consider their mother would do if they were to perform a specific behavior, for example: “What would your mother do if you hit a dog with a stone?” The four response options depict the authoritarian, democratic, permissive and neglectful style and children had to choose one of them.

Neuropsychological battery for preschoolers.33 This battery assesses three different processes regarding executive functions in children from 3 to 6 years old: inhibitory control, mental flexibility and working memory. Indices can be obtained for these three main areas, as well as an overall performance index. Cronbach α is 0.75 which is considered as high, and test-retest reliability is 0.81.

Inhibitory Control index included tests of motor response inhibition, inhibition of automated responses and delay of gratification task. Working memory included digits backwards, Corsi blocks backwards and pointing of images in a reversed order. Flexibility index included a classification and a search task.

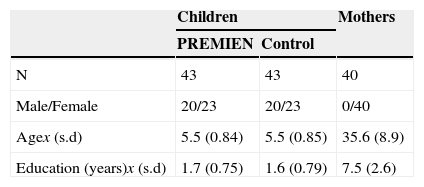

ResultsMothers’ age range was between 22 and 48 years old (x=35.6, s.d.=0.8.9) and level of education was between 5 and 9 years (x=7.5, s.d.=2.6). Children were between 3 and 6 years old (x=5.5, s.d.=0.84).

Table 1 shows the demographics of the mothers and children sample.

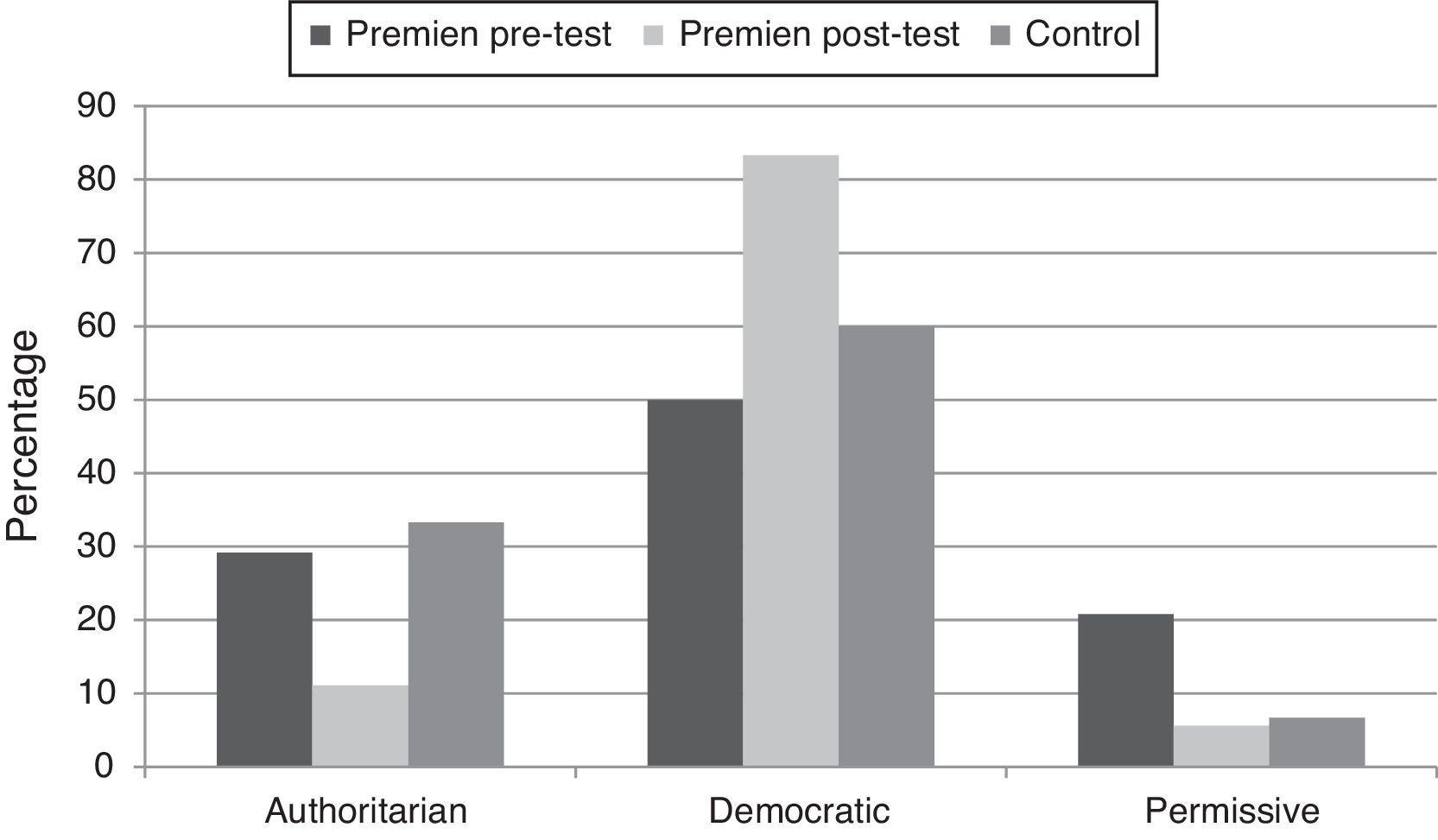

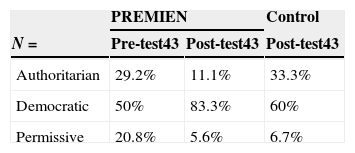

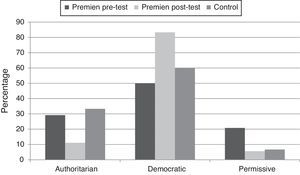

At pretest, 29.2% of children perceived their mother parenting style as authoritarian, while 50% perceived it as democratic and 20.8% as permissive. None of the children perceived his mother as neglectful either at pre or post test, nor in the control group. Upon completion of the PREMIEN program, there was a significant increase of 33% of the children who perceived their mother as democratic, while the percentage of the authoritarian style decreased 18% and the permissive one decreased 15% (x2 (2, n=43)=14.156, p<05). The control group results showed that children perceived their mother parenting style as authoritarian 22% more than the PREMIEN group at post test, whereas 23% less children perceived their mother as democratic and 1% more children perceived their mother as permissive compared to the PREMIEN group at post test (x2 (2, n=80)=12.704, p<0.05). These results are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1.

Parenting style perceived by children.

| PREMIEN | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N = | Pre-test43 | Post-test43 | Post-test43 |

| Authoritarian | 29.2% | 11.1% | 33.3% |

| Democratic | 50% | 83.3% | 60% |

| Permissive | 20.8% | 5.6% | 6.7% |

Percentage of parenting style perceived by children in the PREMIEN group at pre and post test and the control group at post test.

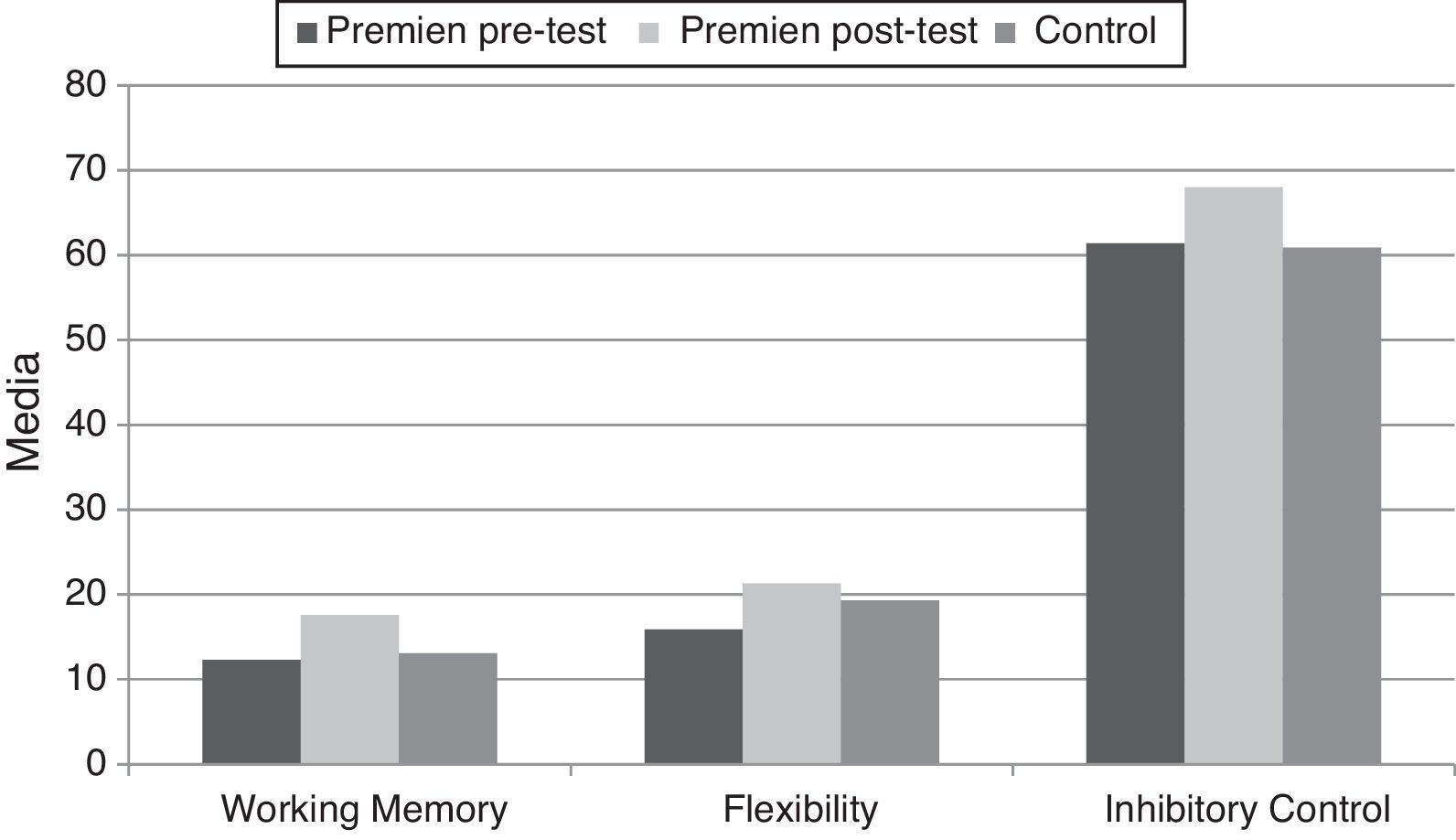

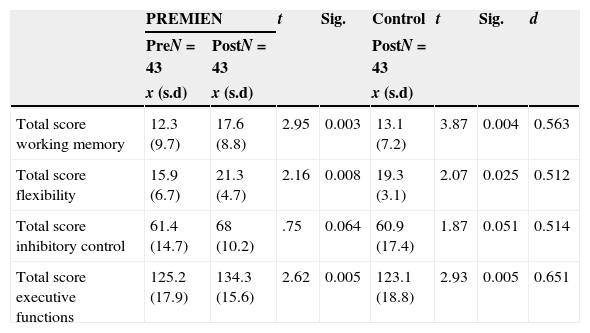

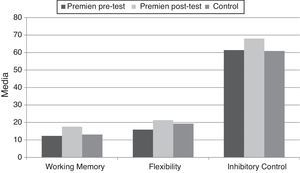

Scores of individual tasks of each function were combined in order to obtain the total score for the indices of inhibitory control, working memory and flexibility. Table 3 shows results at pre and post test of the PREMIEN group. As it can be observed, the children whose mothers attended the program increased their scores in all indices of the battery. Significant increases were found for working memory, flexibility and for the total executive functions indices.

Neuropsychological battery for preschoolers.

| PREMIEN | t | Sig. | Control | t | Sig. | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PreN=43 | PostN=43 | PostN=43 | ||||||

| x (s.d) | x (s.d) | x (s.d) | ||||||

| Total score working memory | 12.3 (9.7) | 17.6 (8.8) | 2.95 | 0.003 | 13.1 (7.2) | 3.87 | 0.004 | 0.563 |

| Total score flexibility | 15.9 (6.7) | 21.3 (4.7) | 2.16 | 0.008 | 19.3 (3.1) | 2.07 | 0.025 | 0.512 |

| Total score inhibitory control | 61.4 (14.7) | 68 (10.2) | .75 | 0.064 | 60.9 (17.4) | 1.87 | 0.051 | 0.514 |

| Total score executive functions | 125.2 (17.9) | 134.3 (15.6) | 2.62 | 0.005 | 123.1 (18.8) | 2.93 | 0.005 | 0.651 |

x=media, s.d=standard deviation, sig.=p<0.05. The table shows comparisons between results at pre and post test of the PREMIEN group, and comparison at post test between PREMIEN and control group.

When the PREMIEN group was compared to the control group at the end of the program, significant differences were found for working memory, inhibitory control, flexibility and the total score of executive functions. Effect size analysis showed a moderate effect on the three indices of the battery as well as for the total score. The results are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 2.

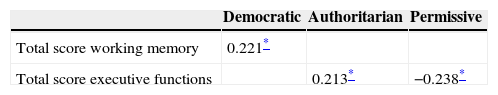

Additionally, we made a correlation analysis with post test data from the children in the PREMIEN program group regarding their perceived parenting style and the total score for working memory, inhibitory control, flexibility and the executive functions index. We found that the executive functions total score is positively correlated with the authoritarian style and negatively correlated with the permissive style, while the working memory total score is positively correlated with democratic parenting style. These results are shown in Table 4.

DiscussionThe objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of the PREMIEN program on executive function development in preschool children and on the perception of their mother's parenting style. Results showed that PREMIEN program might have an influence on children's cognitive development, specifically in working memory and flexibility functions and in children's perceived parenting style likely attributable to mothers’ change in parenting behaviors.

Previous work has showed that parenting style may be a protective factor for children living in adverse environments characterized by violence and poverty. This influence seems to be exerted through parent's awareness of their children's physical, affective and cognitive needs.23,35 The PREMIEN program32 aimed to providing information to mothers that allow them to be sensitive and responsive to their children when interacting with them. At post test, children perceived a change in their mother's parenting style, authoritarian and permissive style diminished while an increase in the democratic style was observed. This might not only impact in immediate behavioral management of the child, but also in providing a supporting environment which in turn might contribute to the child mental health, personality development and subsequent attitudes toward social life in general.22,36

The risk context in which children live in the communities where the program was implemented, not only influences the presence of social, emotional or behavioral maladjustment such as exhibiting violent or addictive behaviors, but also affect their cognitive development. In this sense it is an important finding the fact that children whose mothers attended the PREMIEN program had improved their scores in cognitive processes such as working memory, which allows them to maintain and manipulate information to achieve immediate and long-term goals as well as their ability to switch between different response options and strategies to solve problems. The preschool period is characterized by changes in the development of language, symbolic thought and self-knowledge which allows the development of a self-regulated and directed behavior toward goals.14,30 Therefore, this developmental stage is relevant to the attainment of different cognitive processes considered as executive functions. It has been pointed out that preschool children who show functional working memory abilities and inhibitory control skills perform better on reading and math measures when assessed between 6 and 8 years old; furthermore, this advantage seems to remain even at college years.31,37

Correlation analysis showed that both democratic and authoritarian styles are positively associated with an increase in the score of tasks of executive functions. Psychological research has showed that both styles provide a structured framework for children behavior26; thus this might influence development of executive functions through children's compliance and knowledge of rules and consequences to their behaviors. Democratic style, however, adds an affective factor and consideration of children's needs in parent-child interactions. On the other hand, the permissive style is characterized by absence of consistent rules and limits to child behavior, and correlation analysis showed a negative association. This parenting style promotes poor self-regulation, thus affecting an adequate development of executive functions. Although correlation indices are low, they point to the importance of parenting style in cognitive development in preschool children. Different parenting styles would promote certain behaviors, skills and abilities which might facilitate or impede cognitive attainments.

Overall, these results might support the notion that when parents provide high quality stimulation, both cognitive and emotional, even in high risk environments, children are able to improve their cognitive abilities and even perceive a change in their mother's behavior in everyday interactions.

Conflict of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.