Although smoking is the main risk factor, it is not the only one. Current medical evidence shows that airflow limitation also develops for other reasons.

ObjectiveOur main objective was to determine risk factors which are associated with chronic pulmonary disease, among patients of 40–85 years old at Internal Medicine and Pneumology Departments at the Jose Carrasco Arteaga and Vicente Corral Moscoso Hospitals.

Materials and methodsThis is a case–control study. Our sample was calculated with a 95% confidence interval, an 80% ratio of statistical power, an odds ratio of 3 and a 10% exposure factor with its lowest frequency; a pairing procedure was applied according to gender and age and subjects entered the study sequentially.

ResultsIn all, 318 patients were evaluated, 106 of whom were cases and 212 controls. Both groups were similar in age and the same gender (P>.05). Males constituted 72.3%, with an average age of 62.4 years (±13.1D.E.). An index of over 20 pack years was a risk factor for COPD (OR: 9.03, 95% CI: 3.76–21.72; P=.000). In the case of biomass fumes, this was an exposure index of over 100h/year (OR: 9.65, 95% CI: 4.87–19.32, P=.000). Dust exposure, air pollution and a family history of COPD in patients’ parents were not risk factors for COPD.

ConclusionsRisk factors for COPD were attributable to smoking and biomass smoke exposure.

El tabaquismo es el principal factor de riesgo para enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC), pero no es el único. La evidencia médica actual demuestra que la limitación al flujo aéreo también se desarrolla por otras causas.

ObjetivosDescribir el perfil demográfico de los pacientes con EPOC e identificar posibles factores de riesgo para su desarrollo en sujetos entre 40 y 85 años en los servicios de neumología y medicina interna de los Hospitales José Carrasco Arteaga y Vicente Corral Moscoso en la ciudad de Cuenca, Ecuador.

MétodosEstudio multicéntrico de casos y controles. Se reclutó como casos a personas entre 40 y 85 años con diagnóstico de EPOC y como controles a personas de la misma edad sin diagnóstico previo de EPOC y que no presentaban síntomas de EPOC en el momento de realizar el estudio. La muestra se calculó sobre la base del 95% de nivel de confianza, 80% de poder estadístico, OR de 3 y 10% del factor de exposición con más baja frecuencia; se pareó por edad y sexo e ingresaron al estudio de manera secuencial.

ResultadosSe evaluaron 318 sujetos, 106 casos y 212 controles. Los grupos fueron similares en promedio de edad y sexo (p> 0.05). El 72.3% fueron hombres; el promedio de edad fue 62.4 años (±13.1D.E.). El índice paquetes/años superior a 20 resultó ser factor de riesgo para EPOC (OR de 9.03, IC95%, 3.76 – 21.72; valour de p = 0.000), al igual que la exposición al humo de leña en horas/años mayor a 100 (OR de 9.65, IC 95% 4.87 – 19.32; valour de p = 0.000).

ConclusionesLos factores de riesgo para EPOC son exposición al tabaco y humo de leña.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a worldwide public health problem.1 The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines COPD as a common, preventable and treatable disease characterised by progressive airflow limitation.2 The prevalence of COPD in those aged between 40 and 80 years in Spain varies between 9.1%, according to the IBERPOC3 study, and 10.2% according to the EPI-SCAN study (95% CI: 9.2–11.1).4

Worldwide, this disease is the fourth cause of mortality and its prognosis is linked to multiple factors related to the severity of the disease.5 The PREPOCOL study shows that the prevalence of COPD is 8.9% in over-40-year-olds.6 In the WHO 2014 records, there are 65 million COPD patients globally and it is estimated that by 2030 the disease will have been become the third leading cause of death and the fourth for disability worldwide.7

The PLATINUM study concludes that in Latin America the lowest prevalence of COPD is 7.8%, in Mexico, and 19.8%, the highest, in Uruguay. The rate is higher in men than in women, passive smokers, and those exposed to woodsmoke and dust.8 Smoking is the main risk factor and the most studied.9 It is of great concern that more and more non-smokers are developing the disease, and this has been the starting point for new research on other associated factors.10 There is overwhelming statistical evidence to suggest that this is not the only one.10 When considering the possibility of extending these categories in order to catalogue associated factors, this condition will affect more those over 40, thus becoming a major public health problem.11 The American Lung Association cites exposure to dust, environmental pollution and inherited genetic disorders such as homozygous deficit of alpha-1-antitrypsin, as risk factors for COPD.12

Hu et al. mention that over the past decade, COPD has become a worldwide public health problem, and also noted as a risk factor exposure to smoke from burning biomass (firewood), especially in unventilated, confined interiors.13 The Bolivian Institute of Altitude Biology in the Faculty of Medicine at the Universidad Mayor de San Andres in Bolivia concluded that in la Paz, the prevalence of COPD is 12.9%, and noted that there are other factors apart from smoking that cause disease, such as the use of firewood, environmental pollution and workplace exposure: data that should be considered when further research is undertaken.14 The use of firewood for cooking and heating homes is common in developing countries.15

The association between COPD and woodsmoke has been demonstrated in several epidemiological studies, some of which were conducted in Latin America by Dennis et al.,16 and Pérez-Padilla et al.17 in Mexico; Luna in Guatemala,18 and Albalak in Bolivia.19 Most studies associate this with chronic respiratory symptoms. Dennis and Pérez Padilla link exposure time with spirometry studies and describe a direct relation between frequency of COPD, respiratory symptoms and increased exposure to woodsmoke.16,17 A big question remains as to whether woodsmoke, the working environment, hereditary genetic factors and pollutants in our environment could be risk factors. The aim of this paper is to describe the demographic profile of patients with COPD and identify possible risk factors for the development of the disease in individuals between 40 and 85 years attending two general hospitals in Cuenca, Ecuador.

Materials and methodsStudy designTo undertake the FARIECE study (risk factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the city of Cuenca, Ecuador), a multicentre, case–control study was designed and implemented between January 2011 and December 2012 at the Pneumology and Internal Medicine Departments (inpatient and outpatient) at the Carrasco Arteaga and José Vicente Corral Moscoso Hospitals, in the city of Cuenca, Ecuador. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research and Bioethics Committees at the University of Cuenca Medical School at the José Carrasco Arteaga Hospital and Vicente Corral Moscoso Hospital in Ecuador.

Population and field of studyTo recruit patients, doctors specialising in pneumology and internal medicine at the two hospitals were involved. The diagnosis of COPD was based on GOLD guidelines, supported by clinical history and lung function tests that demonstrated airflow limitation (ratio of FEV1/FVC<.70 pre- and post-bronchodilator), and the fact that this limitation was not reversible after bronchodilation testing (FEV1<80% of the predicted value and a FEV1/FVC<70% after using salbutamol, with no reversibility). Cases selected were subjects with a clinical and spirometry diagnosis of COPD, between 40 and 85 years old, who were attending inpatient and/or outpatient units. As controls, subjects between 40 and 85 years with no diagnosis of COPD and normal spirometry were selected. These subjects were inpatients and/or outpatients. The controls had to be included in the first 7 days after identification of each case, and they could have no family relationship between each other.

Patients excluded were those with community-acquired pneumonia, congestive heart failure, chronic or pulmonale, nosocomial pneumonia or ventilator-caused, tuberculosis, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, spirometry consistent with an obstructive pattern with reversibility of over 12%, or 200ml, after salbutamol; restrictive or mixed spirometry pattern; or exacerbation in their lung disease over the previous 4 weeks. Also excluded were patients with any physical or mental impairment that would hinder running diagnostic tests, and people who had not signed informed consent to participate in the study.

The sample was calculated using multiple, stratified probability sampling without replacement, based on a 95% confidence interval; 80% statistical power; OR 3; and 10% of the lowest rate of exposure factor. Subjects were paired by age and sex and entered the study sequentially. In the first phase we worked with medical specialists in Pneumology and Internal Medicine at the two hospitals. Taking part were two pneumologists and 3 internists from each hospital, i.e. 2 teams of 5 specialists who each contributed 159 subjects, 53 cases and 106 controls.

In the second phase, a specialist at each centre was selected from among professionals with experience in both clinical and epidemiological research to coordinate their group. The third phase consisted of patient selection. These were selected by systematic sampling, obtained from the daily list of hospitalised patients and from patients with an appointment with a specialist who was taking part in the study. These patients had to meet all the inclusion criteria and none of the previously mentioned exclusion criteria. In order to have 2 controls per case, 315 patients had to be evaluated.

Questionnaires on data collectionEach specialist participant filled in a questionnaire on patient data collection. This had to be completed at one single medical visit and included socio-demographic data on smoking habits, personal and family history, comorbidities, treatment, spirometry data, diagnosis and probable known risk factors. The data on personal and family history and comorbidity were reported by patients and/or taken from medical records. We defined the variables studied on the basis of the PLATINO21 study: current smoking was defined as any number of cigarettes smoked in the previous 30 days; the number of cigarettes smoked currently; and the number of cigarettes smoked per day currently; the number of cigarettes smoked over the subject's lifetime; and the total number of cigarettes smoked, on average, per day, over the entire period during which the subject had smoked in his/her life. Subjects who had smoked less than one cigarette per day in one year were considered non-smokers. Also included was: the age at which subjects had stopped smoking, and the age at which they had given up smoking completely.

The rate of smoking exposure was classified into two groups. The first group was designated low risk. The first two categories of risk classification proposed by Villalba and cols22 were used (no risk and average risk). The second group was designated as a high-risk group, taking the last two categories of this classification (acute risk and high risk) and including exposure to woodsmoke as background for the use of firewood in the kitchen stove or for home heating. Other considerations were level of education, taken as the last course completed at school; exposure to dust in the workplace; duration of exposure to dust; and the rate of exposure to smoke for subjects exposed to more than 200h/year (result of multiplying the number of hours exposed daily by the years of exposure to woodsmoke). The risk of COPD was found to be 75 times higher than in people without this exposure.17

Pulmonary function testsAll cases and controls underwent base line and post bronchodilator spirometry tests. The recommendations of the European Respiratory Society and the American Thoracic Society20 were followed to ensure reproducibility of the data obtained.

Statistical analysisThe population taken for statistical analysis included all selected patients who met the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Descriptive statistics of all parameters were produced, including measurement of central tendency and dispersion with its two tailed confidence interval of 95% for quantitative variables, and absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables. Pairing was by age and sex. In the comparison of independentw variables (cases versus controls) and odds ratio, confidence interval of 95% was obtained. Statistical significance was calculated from the P value. The Student t test was used in the case of quantitative variables. The SPSS statistical package, version 20, was used for all statistical analyses.

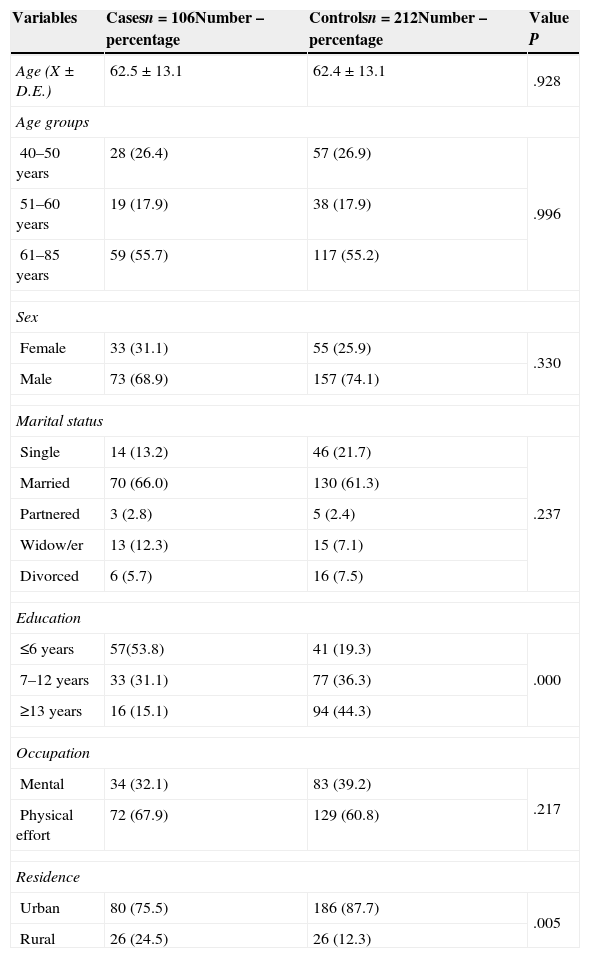

ResultsA total of 10 researchers recruited 318 patients, 106 cases and 212 controls. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The average age in the case group was 62.5 years of age, with standard deviation (SD)±13.1; and in the control group: 62.4 years of age with standard deviation (SD) of ±13.1. Average age in the case group and controls was similar (P-value .928). A total of 88 women (27.7%) and 230 men (72.3%) were located, of whom 73 were male cases (68.9%) plus 157 male controls which constituted 74.1% of the total. Contrasting these proportions with the Chi-square test gave a P-value of .330, thus confirming that the groups (both cases and controls) were similar for the gender variable. The lower limit for age was 40 and the upper limit was 85; the median was 63 years; the 25th percentile was 50 and the 75th percentile was 74.

General characteristics of the study group.

| Variables | Casesn=106Number – percentage | Controlsn=212Number – percentage | Value P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (X±D.E.) | 62.5±13.1 | 62.4±13.1 | .928 |

| Age groups | |||

| 40–50 years | 28 (26.4) | 57 (26.9) | .996 |

| 51–60 years | 19 (17.9) | 38 (17.9) | |

| 61–85 years | 59 (55.7) | 117 (55.2) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 33 (31.1) | 55 (25.9) | .330 |

| Male | 73 (68.9) | 157 (74.1) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 14 (13.2) | 46 (21.7) | .237 |

| Married | 70 (66.0) | 130 (61.3) | |

| Partnered | 3 (2.8) | 5 (2.4) | |

| Widow/er | 13 (12.3) | 15 (7.1) | |

| Divorced | 6 (5.7) | 16 (7.5) | |

| Education | |||

| ≤6 years | 57(53.8) | 41 (19.3) | .000 |

| 7–12 years | 33 (31.1) | 77 (36.3) | |

| ≥13 years | 16 (15.1) | 94 (44.3) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Mental | 34 (32.1) | 83 (39.2) | .217 |

| Physical effort | 72 (67.9) | 129 (60.8) | |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 80 (75.5) | 186 (87.7) | .005 |

| Rural | 26 (24.5) | 26 (12.3) | |

For their analysis, they were classified into three age groups (40–50 years; 51–60 years; and 61–85 years of age). The highest percentages were for patients aged over or equal to 61 years: 59 cases (55.7%). Among the group aged 40–50 years old, 28 cases were identified (26.4%) and among those aged 51–60 years old, 19 cases (17.9%) were identified. The predominant marital status in the case group was married: 70 patients (66%), followed by single: 14 patients (13.2%). Of the 318 patients, 110 patients (34.6%) were studied over a period of 7–12 years and 110 patients (34.6%) were studied for 13 years or longer. Most cases had no education whatsoever or had only completed primary education. Out of all the cases we found a total of 72 patients whose occupation required physical effort, i.e. 67.9% or 34 patients. Those with a mental occupation represented 32.1%.

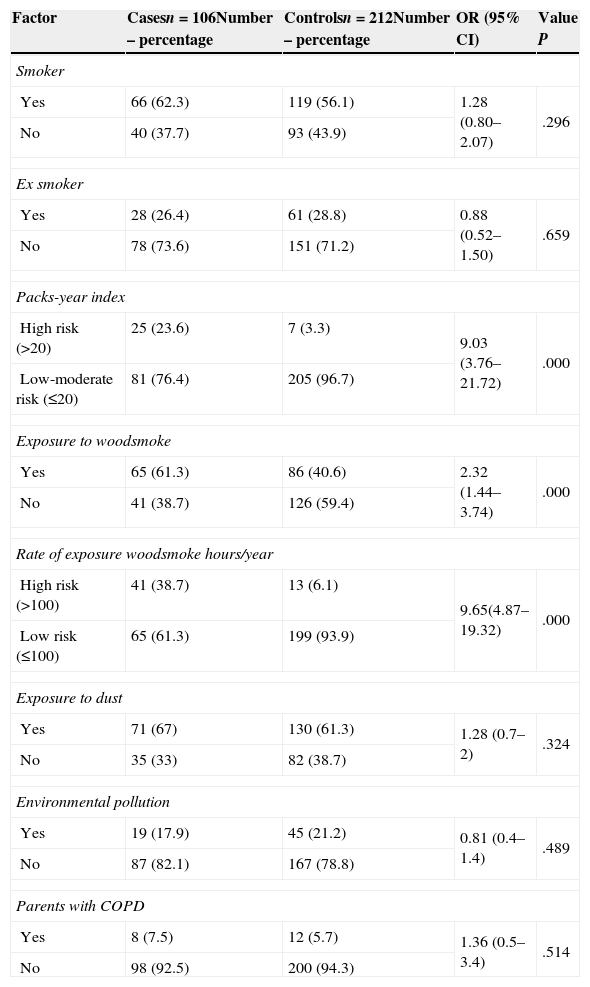

By correlating the P-value, odds ratios and CI of 95% for the groups analysed it was found that a pack-year index of over 20 proved to be a risk factor for COPD (OR: 9.03, 95% CI: 3.76–21.72 and P-value of .000). For exposure to woodsmoke this ratio was h/year over 100 (OR: 9.65, 95% CI: 4.87–19.32; P-value of .000). Full patient details are shown in Table 2. In the case group with a total of 106 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 66 (62.3%) were smokers and 40 (37.7%) were not. In the control group, out of a total of 212 patients, 119 (56.1%) were smokers. These data provide an OR of 1.28 (95% CI: 0.80–2.07) and a P-value of .296. Out of 106 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 28 (26.4%) were former smokers and 78 (73.6%) were not. Out of 212 disease-free patients, 61 (28.8%) were former smokers and 151 (71.2%) were not. This gave an OR of 0.88 (95% CI: 0.52–1.50) and a P-value of .659. In the case group a total of 106 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 25 (23.6%) qualified as high risk on the pack-year index and 81 (76.4%) qualified as low-moderate risk. In the control group, a total of 212 patients, 7 (3.3%) were at high risk on the pack-year index, and 205 (96.7%) were low-moderate risk.

Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and smoking, woodsmoke, dust, environmental pollution and genetic factors.

| Factor | Casesn=106Number – percentage | Controlsn=212Number – percentage | OR (95% CI) | Value P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoker | ||||

| Yes | 66 (62.3) | 119 (56.1) | 1.28 (0.80–2.07) | .296 |

| No | 40 (37.7) | 93 (43.9) | ||

| Ex smoker | ||||

| Yes | 28 (26.4) | 61 (28.8) | 0.88 (0.52–1.50) | .659 |

| No | 78 (73.6) | 151 (71.2) | ||

| Packs-year index | ||||

| High risk (>20) | 25 (23.6) | 7 (3.3) | 9.03 (3.76–21.72) | .000 |

| Low-moderate risk (≤20) | 81 (76.4) | 205 (96.7) | ||

| Exposure to woodsmoke | ||||

| Yes | 65 (61.3) | 86 (40.6) | 2.32 (1.44–3.74) | .000 |

| No | 41 (38.7) | 126 (59.4) | ||

| Rate of exposure woodsmoke hours/year | ||||

| High risk (>100) | 41 (38.7) | 13 (6.1) | 9.65(4.87–19.32) | .000 |

| Low risk (≤100) | 65 (61.3) | 199 (93.9) | ||

| Exposure to dust | ||||

| Yes | 71 (67) | 130 (61.3) | 1.28 (0.7–2) | .324 |

| No | 35 (33) | 82 (38.7) | ||

| Environmental pollution | ||||

| Yes | 19 (17.9) | 45 (21.2) | 0.81 (0.4–1.4) | .489 |

| No | 87 (82.1) | 167 (78.8) | ||

| Parents with COPD | ||||

| Yes | 8 (7.5) | 12 (5.7) | 1.36 (0.5–3.4) | .514 |

| No | 98 (92.5) | 200 (94.3) | ||

These data provided an OR of 9.03 (95% CI: 3.76–21.72) and a P-value of .000. A total of 41 COPD patients (38.7%) were found to be high risk on the h/year index for exposure to woodsmoke and 65 (61.3%) were at low risk. In the control group, 13 of the 212 patients (6.1%) were found to be at high risk after we obtained their hours/year index for exposure to woodsmoke, and 199 (93.9%) were low risk. These data provided an OR of 9.65; CI: 4.87–19.32 (95%) and a P-value of .000. The dust exposure data give an OR of 1.28; CI: 0.7–2 (95%) and a P-value of .324, which is not a statistically significant risk factor. Nor was the exposure to environmental contamination variable with an OR of 0.81; CI: 0.4–1.4 (95%) and a P-value of .489, nor a history of father or mother with COPD with an OR of 1.36; CI: 0.5–3.4 (95%) and a P-value of .514.

DiscussionOur results show that the variables associated with the presence of COPD in a population between 40 and 85 years of age were smoking and exposure to woodsmoke. In Ecuador, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses,23 COPD is the third cause of mortality in Ecuador. It is therefore possible to intervene and change this situation in our environment, with the awareness that its main risk factors can be worked on. When comparing the percentage results with others conducted worldwide, we found that COPD occurs in people aged over 60, with an average age of 62. This can be observed in most studies in neighbouring countries, such as the Colombian study, PREPOCOL.6

One of the most interesting findings among the subjects in our sample is the fact that the risk of developing COPD is low in the fourth decade of life, compared with later ages. Our results indicate that the less educated the patient, the greater the risk of developing COPD. However, at present there are no consistent data establishing a clear link between the risk of developing COPD and level of education, which could be a way of assessing socioeconomic status. Paradoxically, the presence of dust in the home and workplace does not seem to be related to the diagnosis of COPD, which is consistent with reports on innocuousness, if the exposure time is short. However there is a bias here, since this variable has not been researched. In our study, we show that family history as a risk factor for the diagnosis of COPD is not significant. It was not confirmed whether being a smoker or former smoker was a major risk factor.

We took the operational definition of “smoker” in the PLATINO8 study, and in our study we saw that being a smoker was not a risk factor. The explanation may be that the smoking variable was applied using non-smoker, smoker and former smoker but it did not include how many cigarettes were smoked per day.

To associate the risk of COPD and number of cigarettes smoked, we used the packs-year index. Patients in a high risk category (over 20, using the packs-year smoking index) were statistically significant. This result is related to other analytical studies, for example, Amigo et al.24 show that patients with COPD are heavier smokers than those without the disease. Heavy smokers are at 4 times greater a risk of disease than non-smokers. We also found an association between COPD and exposure to woodsmoke when the hours/year ratio was applied, especially in the case of patients in the high risk category (more than 100h/year). The results presented for both smoking and exposure to woodsmoke - as these were modifiable risk factors – are important for primary prevention.

Women who reside in and come from rural areas have been exposed to biomass smoke, this being the main risk factor. Women in our society and, even more so, those living in rural areas, and are being or have been exposed to woodsmoke, are still relegated from childhood to tasks of housework and food preparation and have no opportunity to visit the doctor's surgery. Worse still, they are not able to have an early lung function assessment. Therefore, a clinical history from the general practitioner who is working in their social services in a rural area is required to investigate the possible risk factors of COPD triggers.

Women and children living in rural areas are a vulnerable group as regards suffering from lung diseases, which are a consequence of inhaling toxins from biomass combustion. The idiosyncrasy of our population, coupled with poverty, is the main cause identified in the use of biomass as fuel, and poverty is precisely the main barrier to introducing change and using other less harmful fuels.

Healthcare policies must develop strategies to prevent pulmonary, cardiovascular and other chronic diseases which are the consequence of exposure to these indoor air pollutants. Mechanisms must be sought to warn people of the harmful effects of smoking and biomass smoke (wood for burning) on lung health. There are a number of different variables associated with the development of COPD and a knowledge of these can help prevent the onset of this disease in this population. Therefore, longitudinal studies are required to explain the role of these factors in the development of the disease.

FundingThis study was self-financed by the authors.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.