Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is an autoimmune disease that affects the skin and mucous membranes. It is caused by antibodies directed against desmoglein 3 which leads to the breakdown of the junctions between keratinocytes in the suprabasal epidermis, causing flaccid blisters. Nail involvement in PV has been associated with chronic PV and immunosuppressive therapy, which can increase the risk of bacterial, viral or fungal infection in the nail apparatus.

ObjectivesTo determine which species cause onychomycosis in patients with PV treated with prednisone 1mg/kg/day.

Materials and methodsAn observational, descriptive study was performed in 169 patients: 85 were diagnosed with PV and treated with prednisone at a dose of 1mg/kg/day (patients), and 84 without PV and not treated with steroids (controls).

ResultsThe species most commonly isolated in the PV group was Trichophyton rubrum (29%), followed by Trichophyton mentagrophytes (6%), non-dermatophyte moulds (3%) and Candida albicans (3%). However, in 59% of cases, the causative agent was not identified.

ConclusionsThe presence of onychomycosis in patients with PV was not associated with the use of glucocorticoids; no greater prevalence of onychomycosis was observed in patients without PV and without steroid therapy.

El pénfigo vulgar (PV) es una enfermedad autoinmune, que afecta la piel y las mucosas, producida por anticuerpos dirigidos contra la desmogleína 3, que lleva a la ruptura de las uniones entre los queratinocitos en la epidermis suprabasal, generando ampollas flácidas. La afección del aparato ungueal en el PV se ha asociado al curso crónico de la enfermedad y a la terapéutica inmunosupresora empleada, lo cual puede incrementar el riesgo de sobreinfección bacteriana, viral o micótica en el aparato ungueal.

ObjetivosDeterminar las especies aisladas como causa de onicomicosis en pacientes con pénfigo vulgar en tratamiento con prednisona a dosis de 1mg/kg/día.

Material y métodosEs un estudio observacional, descriptivo y transversal. Se incluyeron 169 pacientes, de los cuales 85 eran pacientes con PV en tratamiento con prednisona a dosis de 1mg/kg/día (casos) y 84 sujetos sin PV y sin terapia con esteroides (controles).

ResultadosLas especies involucradas en el grupo 1 (PV) tenían como las más frecuente a T. rubrum (29%), seguido de T. mentagrophytes (6%), hongos Moho (3%) y C. albicans (3%), no obstante, en el 59% de los casos no fue posible la identificación de la especie.

ConclusionesLa presencia de OM en pacientes con PV no se asoció al uso de tratamiento esteroide; asimismo no se observó mayor prevalencia de OM en comparación con los sujetos sin PV y sin terapia con esteroides.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is an autoimmune disease of the skin and mucosa. It is caused by antibodies that mainly target desmoglein 3,1–3 resulting in a loss of cohesion between suprabasal keratinocytes. This leads to the formation of flaccid bullae on the skin and mucous membranes that rupture easily to form areas of painful, superficial erosion. PV is considered a severe, incapacitating disease that undermines quality of life and general health. The impact of the disease is directly proportional to the extent of the lesions, the chronicity of the condition, various functional problems, the presence of bacterial or mycotic septicaemia, and the need for immunosuppressant therapy, all of which contribute to morbidity and mortality in these patients.

Nail apparatus involvement is usually found in patients with chronic PV treated with immunosuppressants, such as prednisone alone or in combination with adjuvant therapy, such as disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil and methotrexate, among others). In PV patients, therapy is usually administered for 4–5 years, and this can increase the risk of bacterial, viral and/or mycotic superinfection of the nail apparatus.4

Fungal infections of the nail are caused by dermatophytes, yeasts or moulds; immunosuppressants, poor circulation, diabetes mellitus, injury, HIV infection, chronic injury and humidity will predispose a patient to this type of infection.4

Fungi usually affect the nails of the toes; the principal infectious agents are dermatophytes, such as Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and various species of Candida.5,6

Diagnosis is based on microbiological tests and cultures to isolate the aetiological agent and determine the type onychomycosis (OM) involved, following which specific treatment can be started.7,8

There is scant mention in the literature of nail involvement, such as paronychia, onychodystrophy, onychomycosis, subungual bleeding and discolouration in patients with PV, and no studies have hitherto explored the frequency and pathogenesis of onychomycosis in PV patients compared with healthy subjects. This situation prompted us to conduct a study to determine these parameters.

Materials and methodsThis is an observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study in 169 patients seen at the dermatology outpatient department of the “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga” General Hospital of Mexico from September 2014 to April 2015 (7 months). Patients with a clinical, histological and immunological diagnosis of PV treated with 1mg/kg/day prednisone were included in group 1, and matched for age and sex with an equal number of healthy subjects with no diagnosis of PV or autoimmune disease and not treated with steroids (group 2). Both groups were tested for OM using microscopy studies and clinical tests (culture). All patients were evaluated by the same dermatologist who recorded the following study parameters in the data collection sheet: percentage of body surface area affected by PV, nail involvement, type of OM, topography, and time since onset of OM.

The data were analysed descriptively using measures of central tendency and scatter. The database was compiled in Excel. Binomial regression analysis was used to determine risk factors for onychomycosis. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.

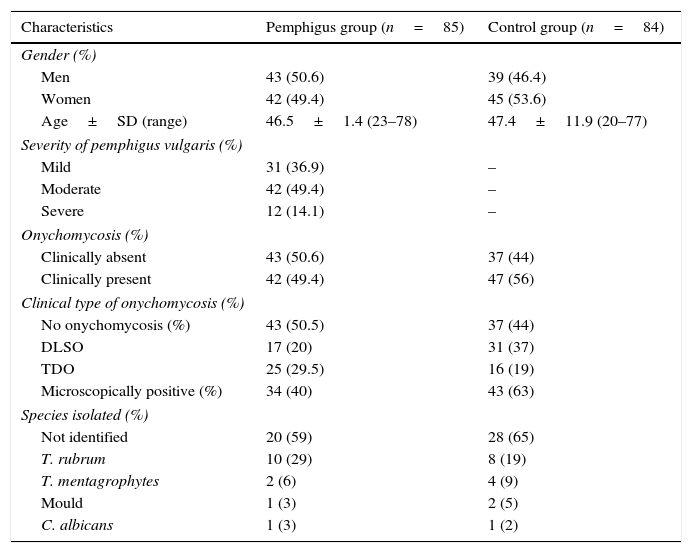

ResultsA total of 169 patients were included in the study, of which 85 (50%) were assigned to group 1 (PV) and 84 (50%) to group 2. No patients were excluded. In group 1, 50.6% were men and 49.4% women; average age was 46.5 years. Most patients were diagnosed with moderate PV.

OM was diagnosed clinically in 49.4% of patients. The most common clinical form was total dystrophic OM (TDO, 29.5%), followed by distal-lateral subungual OM (DLSO) in 20% of patients.

Microscopic examination revealed filaments in 40% of cases. T. rubrum was isolated in 29% of cultured samples, followed by T. mentagrophytes (6%), moulds (3%) and Candida albicans (3%). In 59% of specimens the aetiological agent could not be identified (Table 1).

Characteristics of the study population.

| Characteristics | Pemphigus group (n=85) | Control group (n=84) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | ||

| Men | 43 (50.6) | 39 (46.4) |

| Women | 42 (49.4) | 45 (53.6) |

| Age±SD (range) | 46.5±1.4 (23–78) | 47.4±11.9 (20–77) |

| Severity of pemphigus vulgaris (%) | ||

| Mild | 31 (36.9) | – |

| Moderate | 42 (49.4) | – |

| Severe | 12 (14.1) | – |

| Onychomycosis (%) | ||

| Clinically absent | 43 (50.6) | 37 (44) |

| Clinically present | 42 (49.4) | 47 (56) |

| Clinical type of onychomycosis (%) | ||

| No onychomycosis (%) | 43 (50.5) | 37 (44) |

| DLSO | 17 (20) | 31 (37) |

| TDO | 25 (29.5) | 16 (19) |

| Microscopically positive (%) | 34 (40) | 43 (63) |

| Species isolated (%) | ||

| Not identified | 20 (59) | 28 (65) |

| T. rubrum | 10 (29) | 8 (19) |

| T. mentagrophytes | 2 (6) | 4 (9) |

| Mould | 1 (3) | 2 (5) |

| C. albicans | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

DLOS: distal-lateral subungual onychomycosis; PSO: proximal subungual onychomycosis; SD: standard deviation; TDO: total dystrophic onychomycosis.

In group 2, 34.5% were men and 65.5% women; average age was 57.4 years.

OM was diagnosed clinically in 56% of patients. The most common clinical form was DLSO in 37%, followed by TDO in 19% of patients.

Microscopic examination revealed filaments in 63% of cases. T. rubrum was isolated in 19% of cultured samples. In 65% of specimens the aetiological agent could not be identified.

The following factors were included in the logistic regression analysis: comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, obesity), presence, duration and severity of PV, and dose and dosing interval of systemic steroid and adjuvant). None of the foregoing were risk factors for onychomycosis.

DiscussionOnychomycosis is the most common form of nail disease, being responsible for 50% of nail infections and 30% of superficial mycoses. Most cases of onychomycosis are caused by dermatophytes, mainly T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes var. interdigitale. Together, these cause 90% of fungal infection in toenails, and 50% in fingernails. These are followed by Candida species in 1.7% of toenail infections and 29.2% in fingernails, and finally by moulds.9–11 OM can undermine quality of life, and in immunocompromised patients they can be the route of entry for soft tissue infections and cause fungaemia, thus increasing the morbidity burden and risk of mortality. No studies have as yet determined the aetiological agents associated with OM in patients with PV.

Our study has shown that far from being uncommon in PV patients, OM was found in 49.4% of the study population, with most infections being dermatophytic in origin. The predominant species was T. rubrum, which was isolated in both groups, although more frequently in PV patients, irrespective of the systemic steroid regimen or adjuvant used, disease severity or activity (data not shown). Although this would suggest that PV is a risk factor for OM, this association was not shown on the regression analysis.

In immunocompromised patients, such as kidney transplant recipients, diabetics, patients with lymphoma or those receiving immunosuppressants, the species most frequently isolated are Candida, followed by dermatophytes, and lastly combined infections.12 In PV patients taking immunosuppressants, we found dermatophytes (T. rubrum) to be the primary pathogenic agents of OM, followed by T. mentagrophytes, moulds, and lastly C. albicans. This contrasts with the findings of other studies in immunocompromised populations, and shows that not only immunosuppressants but also PV are important factors in the development of dermatophytic OM.

Nail involvement is found in the later, chronic stages of PV, although it could also be associated with immunosuppressant therapy (which promotes bacterial, viral and/or mycotic superinfection). The nail infections most frequently described in the few studies available on the subject include paronychia, onychodystrophy, onychomycosis, subungual haemorrhage, discolouration or Beau lines, mostly involving the first and second fingers. OM is found in between 20% and 30% of cases.13 In our study, the most commonly found clinical type was TDO in 29.5% of patients, followed by DLSO in 20%. Nail disease is most prevalent in the 40–60 years age group, a finding echoed in our study.

OM usually involves the toes, and incidence is higher in men, possibly due to associated factors.14,15 In our study, incidence was higher in men, the most common site of infection was the toes, and T. rubrum was isolated in most (29%) cases, followed by T. mentagrophytes (6%), moulds (3%), and C. albicans (3%). Similar proportions were found in the control group.

In conclusion, this is the first study in Mexico to focus on the clinical and microbiological patterns of OM among PV patients. In view of its impact on the general health of these patients, it would be advisable to actively screen PV patients for OM. If OM is suspected, scrapings should be taken for microscopic examination and culture to isolate the pathogenesis and administer the best and most effective treatment. OM is more than a mere cosmetic problem. Further studies in different populations are needed to determine the real prevalence of OM and confirm our findings.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.