The purpose of this study is to ascertain the changes in tobacco use and alcohol consumption, as well as the family history related to the risk for chronic disorders in students from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, UNAM), when transitioning from secondary school to university.

MethodologyThe data from the Comprehensive Health Assessment Survey performed on university students by the Department of Health Services (Direccion General de Servicios Medicos, DGSM) was analysed and compared with their previous health state, tobacco use and alcohol consumption, excess weight, obesity and health issues of relatives.

Results593 students participated in the survey, of whom 69.6% were women. The greatest mean BMI variation was between the age of 14 and 16. 1.54% reported having high blood pressure during secondary school and 1.69% during university. In three years, alcohol consumption increased by 32% and tobacco use by 7.6%. As for the relatives’ health state, the predominance of high blood pressure went from 24.1 to 30.4, obesity went from 27.6 to 31.3, tobacco use went from 24.5 to 24.9 and type 2 diabetes mellitus went from 12.8% to 16.2% with p<0.01.

ConclusionsThe changes in risk factors point to a higher risk profile for chronic disorders. Future health damages could be reduced if measures were taken among young people.

Conocer loscambios en el consumo de tabaco y alcohol así como los antecedentes familiares en cuanto a riesgos de enfermedades crónicas, en estudiantes de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), al transitar del bachillerato a la licenciatura.

MetodologíaSe analizó y comparó información de la Encuesta de Valoración Integral de Salud que aplica a universitarios la Dirección General de Servicios Médicos (DGSM), sobre su estado de salud previo, consumo de tabaco y alcohol, sobrepeso, obesidad y problemas de salud de familiares.

ResultadosParticiparon 593 alumnos, 69.6% mujeres. La mayor diferencia de promedio del IMC se presentó entre los 14 y los 16 años. El 1.54% refirió hipertensiónarterial durante el bachillerato y 1.69% en licenciatura. En tres años, el consumo de alcohol se incrementó en un 32% y en 7.6% para tabaco. En cuanto al estado de salud de los familiares, la prevalencia de hipertensión arterial pasó de 24.1 a 30.4, obesidad de 27.6 a 31.3, tabaquismo de 24.5 a 24.9 y diabetes mellitus tipo 2 de 12.8% a 16.2% con p<0.01.

ConclusionesLos cambiosde los factores de riesgo apuntalan hacia un perfil de mayor riesgo para enfermedades crónicas. Actuar en los jóvenes puede reducir daños a la salud a futuro.

In the last few decades, there have been transitions in the health profile of Mexicans, with an increase in the frequency of chronic disorders in children, adolescents and young adults, together with significant social variations that have caused changes in eating patterns, physical activity and the way in which leisure time is viewed. These changes have promoted health risk behaviours.

Among the main risk factors for this type of disorders are ones associated with the environment, stressful situations, a sedentary lifestyle and a high consumption of fats and carbohydrates that turn into excess weight and obesity,1 alcohol consumption and tobacco use at progressively younger ages, with a higher consumption by women,2,3 and other biological risks such as family history and inherited conditions.

It is extremely important to know the behaviour of risk factors to identify preventive actions and strategies. Early detection, check-ups and timely treatments for non-contagious chronic diseases are also important in order to anticipate actions on potentially modifiable risk factors. A 13.6% predominance for metabolic syndrome was found amongst adolescents, and the presence of one or more risk factors was detected as a possible cause for the increase in the likelihood of developing cardiovascular diseases.4

Various risk factors associated with cultural, leisure and free time factors were analysed in students from the Autonomous University of Tlaxcala (Universidad Autonoma de Tlaxcala). Studies in supposedly healthy students were carried out to explore some risk factors: a predominance of excess weight and obesity of 23% and 6%, respectively, was observed; 63% reported not performing any physical activity; 20.1% reported smoking on a daily basis and 22.6% reported consuming alcoholic beverages frequently.5

Excess weight and obesity were observed amongst adolescents nationwide, 32.7% for men and 33.6% for women (NHANES, 2006).1 Risk factors associated with tobacco use in adolescents were the incidence of this habit among relatives, peer pressure and the influence of cultural patterns.6

In schoolchildren between the age of 10 and 17, 23.1% were smokers and, among these, 63.5% smoked on a daily basis. It was found that the older they were, the more physiologically dependent they were.7 The frequency in tobacco use amongst adolescents was also compared in urban and rural areas: in urban settings, tobacco use variations were found according to gender, 27.6% of women used tobacco, whereas the predominance in men was of 19.3%. In rural settings, the predominance of tobacco use was higher in men than in women.2

11% consumed alcohol for the first time between the age of 10 and 12; 68% between the age of 13 and 17 during family reunions, where 17% of relatives used tobacco, 30% consumed alcohol and 8% illegal drugs.8

Amongst university students there were variations according to gender: men regarded tobacco and stress as the most harmful factors, while women indicated an excessive consumption of alcohol. Tobacco use, alcohol abuse, stress and having a hostile attitude were found to be associated with the presence of cardiovascular diseases. Also, we found that men take part in more sports than women and that women try to lose weight more often.9

In conclusion, during the different life stages there were changes in lifestyle, as well as in the consumption of alcohol and the use of tobacco; there were changes in eating patterns and physical activity, and there was a more sedentary lifestyle,10,11 all of which may represent health risk behaviours.

The purpose of this study is to explore and compare the behaviour of some risk factors in chronic disorders through the analysis of the data from the Automated Medical Examination (Examen Medico Automatizado, EMA)12 that the Department of Health Services (DGSM) performed on secondary school students admitted to UNAM's School of Medicine, class of 2010.

MethodologyTo know the behaviour of the risk profile for chronic disorders of the students from the School of Medicine, we performed a comparative analysis with students of both genders from the National Autonomous University of Mexico who answered the EMA and who had their personal weight and height data from secondary school, in addition to having the data for the same variables from university.

Sources of informationThe EMA is a comprehensive health assessment tool composed of three auto-reply documents, structured in 63 large sections, which comprise 210 questions. Except for weight and height, the rest of the data are qualitative.

The data on health issues from close relatives (father, mother and siblings) was analysed putting emphasis on previous and current health issues, such as the existence of neoplasias, type-2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), pneumopathies, cardiopathies, obesity and hypertension (HTA); as well as a history of tobacco use and alcoholism. For analysis purposes, close relatives were grouped under one heading.

Alcohol consumption and tobacco use were deemed negative if during the period under study students reported they had not smoked tobacco or drunk alcoholic beverages; and it was deemed positive if they answered they had used or consumed these substances at some point, even if they did not do so currently. When students were reported as positive, to estimate the age at which usage of both substances was initiated, the life period was divided into: prior the age of 15, between the age of 15 and 17, and older than 17; frequency of tobacco use was divided into 1–3 cigarettes, 4–9, 10–15, and 16 or more cigarettes per week; for alcohol consumption they were asked if they drank once a month, between one to three times a year and specifically at family parties, or if it was once a week, once a month, three or more days a week. The amount of alcohol was established as glasses or beers and consumption was divided into 1, 2–3, 4–5, and 6 or more per occasion.

To define excess weight and obesity, criteria recommended by the Ministry of health in the National Health Chart was used; the Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated by age and gender, by age group both for men and women. In the chart, the population between the age of 10 and 19 was considered as adolescents and as adults when they were over the age of 19.

Statistical analysisAn exploratory analysis of the data from the students who belonged to the class of 2010 was carried out. Kappa concordance was calculated. To know and assess the changes exhibited by medical students from the class of 2010, EMA's data were grouped and analysed, beginning by evaluating the risk factors for chronic disorders. To identify the change over the study period, McNemar's test was calculated for two populations with paired proportions with a level of significance of 95%. To perform the statistical analysis, the SPSS and EPIDAT 3.1 statistical packages were used.

ResultsData from 593 students at the moment of admittance to an intermediate higher education level and to the School of Medicine was used; out of these students, 413 (69.6%) were women. The age interval at the intermediate higher education level fluctuated between 13 and 37, and at a higher level fluctuated between 16 and 40. At the intermediate higher education level, 87.8% were between the ages of 13 and 14, the average being age 15. At a higher level of education, 85.6% were between the ages of 17 and 18, with an average age of 18 and an SD of 1 and 1.5 for women and men, respectively, at both measuring moments. 97.3% finished secondary school in three years and the rest in four years.

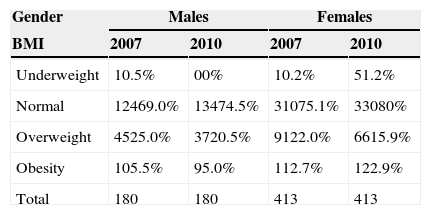

When analysing changes in weight, height and BMI between secondary school and university, it was found that there were greater changes in weight, height and BMI at a younger age. The greatest fluctuation was in a student aged 13, where weight variation was of +15kg, and height variation of +27cm, with a BMI change of −0.1. As for excess weight during the same study period, men went from 25% to 25.5% (p<0.01) and women from 22% to 15.9% (p<0.00) (see Table 1).

Body Mass Index by gender in students from the National Autonomous University of Mexico, class of 2007–2010.

| Gender | Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 2007 | 2010 | 2007 | 2010 |

| Underweight | 10.5% | 00% | 10.2% | 51.2% |

| Normal | 12469.0% | 13474.5% | 31075.1% | 33080% |

| Overweight | 4525.0% | 3720.5% | 9122.0% | 6615.9% |

| Obesity | 105.5% | 95.0% | 112.7% | 122.9% |

| Total | 180 | 180 | 413 | 413 |

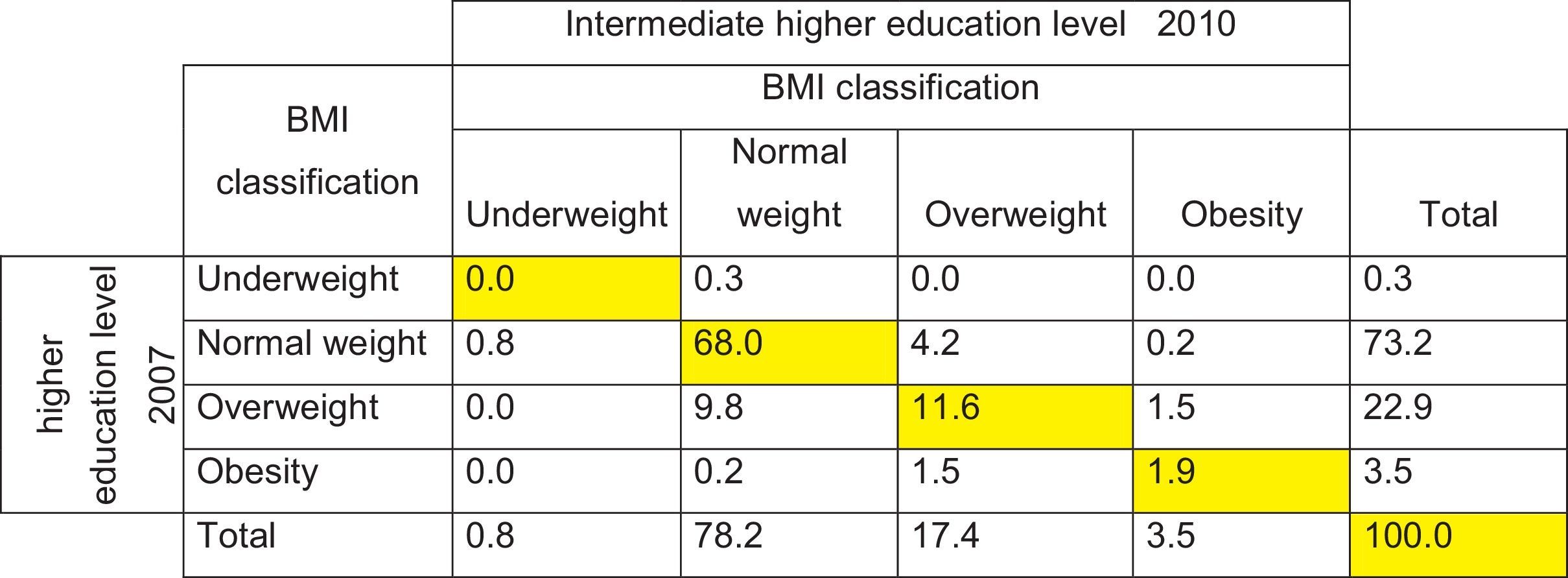

As for the somatometric characteristics, 22.9% at the intermediate higher education level were found to be overweight and 3.5% obese; at a higher level of education, 17% of the students were overweight and obesity did not vary between the first and the second measurement. As shown in Table 2, during the study period, the BMI variation was insignificant; 81.5% of the students did not change their status.

As for the pathological personal history, 1.54% reported having high blood pressure during secondary school and 1.69% during university. The rest of their personal history was not relevant to this study.

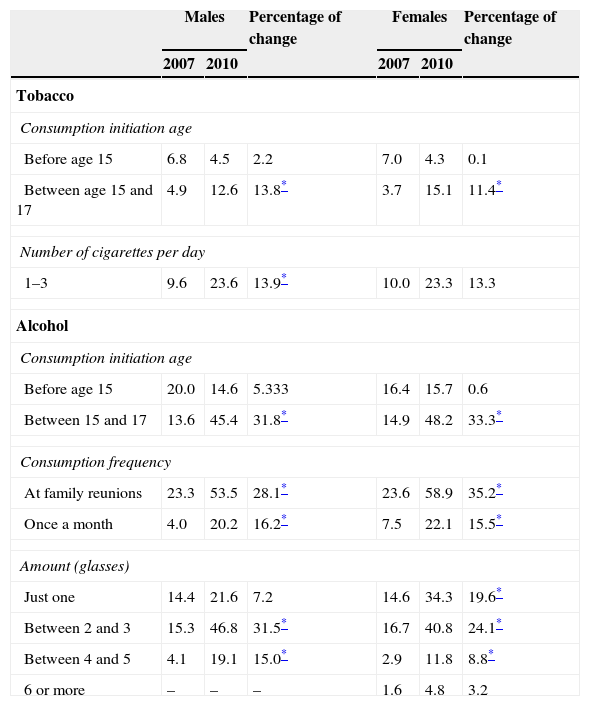

Regarding the habits explored in students, it was found that 2.7% smoked at the intermediate higher education level. Out of this percentage, 62% had done so prior the age of 15 and everyone stated they smoked between one to three cigarettes a day. At university level, 11.3% stated they smoked; 57% started smoking between the ages of 15 and 16, and 76.6% smoked between one to three cigarettes a day. 72.8% of the cases did not change their smoker status during their transition from secondary school to university.

As for alcohol consumption at the intermediate higher education level, 24.1% reported they consumed alcohol occasionally. Of these, 62.2% began drinking alcohol between the ages of 15 and 16; 83.8% consumed alcoholic beverages between one and three times a year at family parties, and 13.2% once a month. At university level, consumption increased by 32.2%: 56.3% of the students reported they consumed alcohol at least occasionally; out of that percentage, 61.3% started consuming alcohol between the ages of 15 and 16. As shown in Table 3, when looking at the percentage of change for this period, there was a significant increase in the consumption of these substances.

Tobacco use and alcohol consumption characteristics in students and percentage of change, 2007–2010. National Autonomous University of Mexico.

| Males | Percentage of change | Females | Percentage of change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2010 | 2007 | 2010 | |||

| Tobacco | ||||||

| Consumption initiation age | ||||||

| Before age 15 | 6.8 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 7.0 | 4.3 | 0.1 |

| Between age 15 and 17 | 4.9 | 12.6 | 13.8* | 3.7 | 15.1 | 11.4* |

| Number of cigarettes per day | ||||||

| 1–3 | 9.6 | 23.6 | 13.9* | 10.0 | 23.3 | 13.3 |

| Alcohol | ||||||

| Consumption initiation age | ||||||

| Before age 15 | 20.0 | 14.6 | 5.333 | 16.4 | 15.7 | 0.6 |

| Between 15 and 17 | 13.6 | 45.4 | 31.8* | 14.9 | 48.2 | 33.3* |

| Consumption frequency | ||||||

| At family reunions | 23.3 | 53.5 | 28.1* | 23.6 | 58.9 | 35.2* |

| Once a month | 4.0 | 20.2 | 16.2* | 7.5 | 22.1 | 15.5* |

| Amount (glasses) | ||||||

| Just one | 14.4 | 21.6 | 7.2 | 14.6 | 34.3 | 19.6* |

| Between 2 and 3 | 15.3 | 46.8 | 31.5* | 16.7 | 40.8 | 24.1* |

| Between 4 and 5 | 4.1 | 19.1 | 15.0* | 2.9 | 11.8 | 8.8* |

| 6 or more | – | – | – | 1.6 | 4.8 | 3.2 |

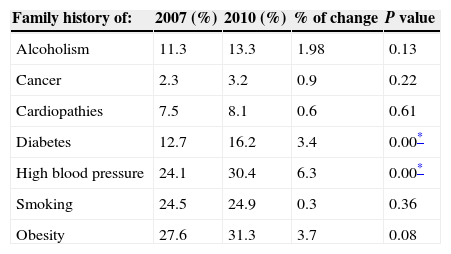

As for the students’ family history, there was 86.5% data correspondence for alcoholism, 81.4% for tobacco use, 86% for cancer, 84.6% for DM2, 68.5% for obesity and 70.8% for high blood pressure. Table 4 shows how the percentage of change increased by 6.3% for high blood pressure, 3.4% for DM2 and 3.70% for obesity, with significant differences, except for obesity for which significance was borderline.

Family members’ health issues reported by UNAM's students 2007–2010.

| Family history of: | 2007 (%) | 2010 (%) | % of change | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcoholism | 11.3 | 13.3 | 1.98 | 0.13 |

| Cancer | 2.3 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 0.22 |

| Cardiopathies | 7.5 | 8.1 | 0.6 | 0.61 |

| Diabetes | 12.7 | 16.2 | 3.4 | 0.00* |

| High blood pressure | 24.1 | 30.4 | 6.3 | 0.00* |

| Smoking | 24.5 | 24.9 | 0.3 | 0.36 |

| Obesity | 27.6 | 31.3 | 3.7 | 0.08 |

N=593.

In general, students are healthy when admitted to the intermediate higher education level and they remain healthy until their admittance to university. However, it is essential to point out that, although the frequency is low, some students have high levels of blood pressure, which is important since it has been discovered that diabetic patients have a history of illnesses such as high blood pressure, overweight and obesity during their adolescence.12

The majority of the participants in this study had a normal BMI with no significant changes during the study period. There were students who had excess weight and obesity, which is important to point out since nationwide in the 2006 NHANES1 there was an increase of 7.8% in overweight and an increase of 3.3% in obesity in the population between the ages of 12 and 19. In turn, an association between BMI increase and an increase in the level of blood pressure was found in adolescents from Mexico City, with a predominance of hypertension by the 95th percentile of 10.0%.13

As for the risk factors deemed modifiable in this study, during the study period, tobacco use increased in 3 out of 100 students and alcohol consumption in 30 out of 100 participants. This is consistent with another study, in which the same results were obtained when comparing alcohol consumption and tobacco use in secondary and university students.14

In this study, the predominance in the consumption of alcohol and tobacco use was high, and there was a significant increase in the consumption of alcohol, at least occasionally. It is considered that the average age at which adolescents start secondary school is 15 and 18 for university. It is important to point out that the levels found in this study are higher than the ones found by the 2012 NHANES,16 where it is indicated that 28.8% of men and 21.2% of women stated they consumed alcohol between the ages of 10 and 19, nationwide. On average, adolescents smoked a tobacco product for the first time at age 14.6, with no difference between men and women. It was found that 20.1% university students smoked on a daily basis and 22.6% reported consuming alcoholic beverages frequently.5

Students reported that the change in tobacco use amongst relatives was not significant, but it was significant for the consumption of alcohol, which coincides with what was reported in the 2012 NHANES15 where it is reported that from 2000 to 2012, tobacco use went down from 22.3% to 19.9% and alcohol consumption rose from 39.7% to 53.9% amongst the adult population. The results found in this study coincide with other studies, where 17% of the children state that their first experience with alcohol was at family reunions. The influence people (friends and family members) exert constitutes a well-known fact, particularly for siblings and parents, with a tendency to consume alcohol and tobacco simultaneously.8

Due to the importance family history and inheritance have as risk factors in the emergence of chronic disorders, it should be pointed out that within the 3-year period the frequency of chronic disorders increased significantly among the students’ close relatives, since it was found that children and adolescents with a family history of DM2 have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, which has been associated with dyslipidaemias16 and 61% of the patients with diabetes has a first-degree relative with DM2, 32% with obesity and 42% with high blood pressure.17

Between the first and the second measurements there was also an increase in the number of close relatives with these disorders, which is important to emphasise, since given the students’ age it could be assumed that their parents are probably young adults. Although these risk factors are not modifiable, it was discovered that at a higher number of risk factors for non-contagious chronic diseases, the probabilities of cardiovascular disease rises,17 with a positive association between the existence of a family history and the existence of metabolic syndrome.18

In the last few decades, there have been alterations in the health profile of Mexicans, with an increase in the frequency of chronic disorders in children, adolescents and young adults. If we know the environments where young people generally grow, and, in particular, if we know the school setting, it can be possible to identify health risk behaviours and carry out actions that contribute to modify them.

Conclusions and recomendationsIn spite of the fact that the student population who participated in this study is apparently healthy, it is necessary to take into account that the follow-up period is brief: the changes observed in the consumption of alcohol and tobacco use are primarily significant within the student population, as well as among close relatives. This is why it is essential to consider and implement campaigns specifically directed towards this population with the aim of cutting their consumption.

By knowing that the more risk factors, the higher the risk of developing chronic disorders, it is imperative to identify preventive actions and strategies, as well as early detection, check-ups and timely treatment for non-contagious chronic diseases, and to anticipate actions on potentially modifiable risk factors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.