The acute renal failure (ARF) contributes to a longer hospital stay, morbidity, mortality and use of resources in critical patients.

The estimate of its incidence was difficult, mainly due to the lack of a generally accepted definition.

ObjectiveTo determine the incidence, risk factors and effects of the ARF in critical patients.

Material and methodsStudy of prospective cohort. Patients hospitalised in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) were included. The population was divided into 4 groups: A: without ARF; B: with ARF at ICU admission; C: ARF developed at the ICU; and D: ARF at the admission, solved and developed again at the ICU. Descriptive and inferential statistics (Student's t, χ2 and ANOVA).

ResultsOf 360 patients, 50.5% were men. The mean age was 49 years. From the total, 145 (40.3%) did not develop ARF (group A). The main comorbidities were diabetes mellitus and high blood pressure. Patients with sepsis, shock and multiple organ failure showed a greater ARF frequency (p<0.001). The ARF incidences were 30.3% in group B, 20.3% in group C and 9.2% in group D. The attributable mortality was 11.8%, 16.6% and 26.1%, respectively. There was a higher use of resources in groups C and D.

ConclusionsThe ARF incidence in critical patients ranges from 9.2% to 30.3%. The main risk factors are sepsis, shock and MODS.

La lesión renal aguda (LRA) contribuye a mayor estancia hospitalaria, morbilidad, mortalidad y consumo de recursos en pacientes críticos.

Estimar su incidencia era complicado, principalmente por la falta de una definición generalmente aceptada.

ObjetivoDeterminar incidencia, factores de riesgo y efectos de la LRA en pacientes críticos.

Material y métodosEstudio de cohorte prospectiva. Se incluyeron pacientes hospitalizados en Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos (UCI). La población se dividió en 4 grupos: A. Sin LRA; B. con LRA al ingreso a UCI; C. LRA desarrollada en UCI; y, D. LRA al ingreso, resuelta y nuevamente desarrollada en UCI. Estadística descriptiva e inferencial (t de Student, χ2 y ANOVA).

ResultadosDe 360 pacientes, 50.5% fueron hombres. La edad media fue 49 años. Del total, 145 (40.3%) no desarrollaron LRA (grupo A). Las principales comorbilidades fueron diabetes mellitus e hipertensión arterial. Los pacientes con sepsis, choque y falla multiorgánica presentaron mayor frecuencia de LRA (p<0.001). Las incidencias de LRA fueron 30.3% en el grupo B, 20.3% en el grupo C y 9.2% en el grupo D. La mortalidad atribuible fue de 11.8%, 16.6% y 26.1%, respectivamente. Hubo mayor consumo de recursos en los grupos C y D.

ConclusionesLa incidencia de LRA en pacientes críticos oscila entre 9.2% y 30.3%. Los principales factores de riesgo son sepsis, choque y SDOM.

Acute renal failure (ARF) is a frequent problem which significantly contributes to morbidity and mortality, particularly in critical patients. It is characterised by the sudden loss of the kidney capacity to excrete waste products, concentrate urine, preserve electrolytes and keep the water balance. It is particularly common in the intensive care unit (ICU), where it is associated to a 50–80% mortality.1–4

In Mexico, different studies have reported differing incidence and mortality rates because there was no accepted ARF definition.5–9

The aim of this study is to assess the incidence, risk factors, effects on the morbidity, mortality and use of resources in patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) at the university general hospital in Mexico, using the updated definition of the group Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN).4

Material and methodsIn this study of the prospective cohort, 18 year-old patients admitted to the ICU of the General Hospital in Mexico were included, from April 2013 to October 2014. Patients with chronic renal disease were excluded.

Demographic information (age, genre), clinical data (urine output per hour by kilogram and creatinine), presence of comorbidities (sepsis, shock, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS)) were collected. The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS 3 (severity of the disease)), modified Brussels scale (organic failure) and Nine Equivalents nursing Manpower use Score (NEMS (use of resources)) were assessed.10–12 The use of resources (invasive mechanical ventilation, continuous drug infusions, blood derivatives, length of stay in the ICU and hospital stay) were recorded.

The ARF was defined as the stage 1 of the AKIN classification, creatinine increase >0.3mg/dL or 1.5–2 times increase in basal value, urine output <0.5mL/Kg/h per six hours 4.

Sepsis was defined as the presence of infection together with systemic manifestations (temperature >38.3°C or <36°C, heart rate >90 heartbeats per minute, tachypnoea, leukocytes >12,000/μL or <4000/μL, systolic blood pressure <90Torr). Severe sepsis such as low blood perfusion induced by sepsis or organic dysfunction (hyperlactataemia, PaO2/FiO2 <300, urine output <0.5mL/Kg/h, creatinine >2mg/dL, bilirrubine >2mg/dL, platelets <100,000/μL).13

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) was defined as the progressive dysfunction of two or more physiological systems considered as the sum of 6 or more points in the modified Brussels scale.11

Patients were divided into four groups. Group A, patients who did not show ARF; group B, patients who already had ARF at the admission to the ICU; group C, patients who developed ARF during their stay at the ICU; and group D, patients who were admitted with ARF which was resolved during their stay and developed again in the same stay at the ICU. Descriptive statistics: Frequencies, proportions, arithmetical means, standard deviations and cumulative incidence of ARF. Inferential statistics: 2-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) test for the dimensional variables and χ2 for non-parametric variables, considering a p value <0.05 significant. The statistical package used was the SPSS v. 13 (SPSS®, Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsDuring the study period, 400 patients were included in the cohort; 31 of them were excluded because they had chronic renal disease and 9 because they did not have full information. 360 cases remained for the analysis.

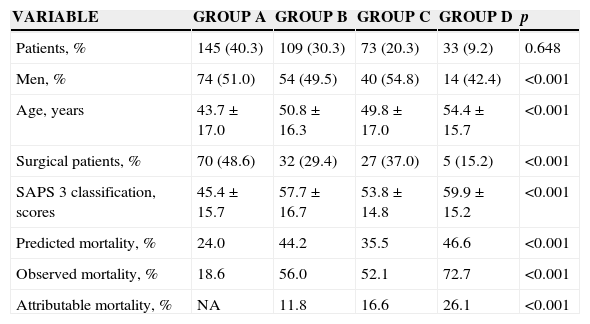

Of the 360 patients, 182 (50.5%) were men. The mean age was 49 years. The information by groups is found in Table 1. Patients with ARF during admission to the ICU, solved and developed it again during their stay in ICU, were the oldest patients, generally came from medical areas and showed a higher severity of the disease (p<0.001, for all the variables). The progressive gradient of attributable mortality between groups from 11.8% in group B to 26.1% in group D stands out.

Comparison among groups.

| VARIABLE | GROUP A | GROUP B | GROUP C | GROUP D | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, % | 145 (40.3) | 109 (30.3) | 73 (20.3) | 33 (9.2) | 0.648 |

| Men, % | 74 (51.0) | 54 (49.5) | 40 (54.8) | 14 (42.4) | <0.001 |

| Age, years | 43.7±17.0 | 50.8±16.3 | 49.8±17.0 | 54.4±15.7 | <0.001 |

| Surgical patients, % | 70 (48.6) | 32 (29.4) | 27 (37.0) | 5 (15.2) | <0.001 |

| SAPS 3 classification, scores | 45.4±15.7 | 57.7±16.7 | 53.8±14.8 | 59.9±15.2 | <0.001 |

| Predicted mortality, % | 24.0 | 44.2 | 35.5 | 46.6 | <0.001 |

| Observed mortality, % | 18.6 | 56.0 | 52.1 | 72.7 | <0.001 |

| Attributable mortality, % | NA | 11.8 | 16.6 | 26.1 | <0.001 |

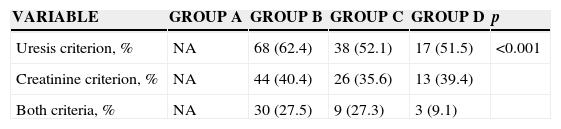

The ARF incidence varied according to the group and criterion used. The group incidences were 30.3% for group B, 20.3% for group C and 9.2% for group D. Therefore, the highest incidences were found when the uresis criterion was used. The lowest incidences were obtained when uresis and creatinine criteria were required (Table 2).

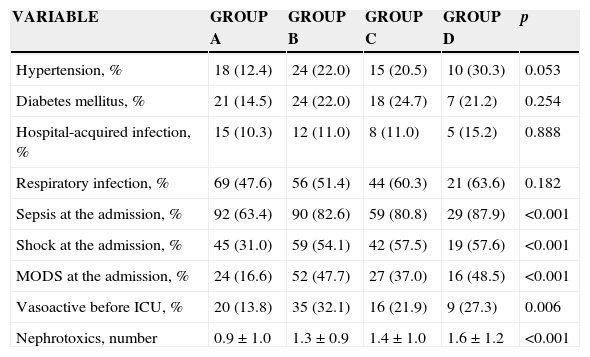

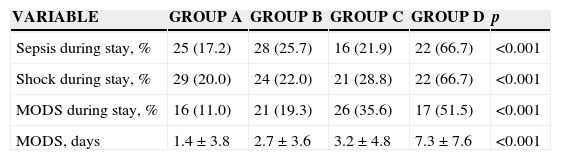

The main comorbidities were diabetes mellitus type 2 and hypertension, with no significant difference among groups. However, a hypertension gradient was found among groups. There were no documented differences among groups regarding the presence and origin of infections (Table 3). However, the presence of sepsis, shock, MODS and the use of vasopressors at admission were frequently found from groups A to D (p>0.001), these conditions having a deleterious effect of on renal function. The relative risks of the presence of sepsis, shock and MODS on admission to the ICU were associated with the ARF development during the stay in the ICU, and were the following: 1.176 (CI 95% 1.051–1.316), 1.441 (CI 95% 1.159–17.91) and 1.376 (CI 95% 1.023–1.851), respectively. The nephrotoxic agents were more used in groups C and D (p<0.001), whereas the vasoactives were more used in groups B and D. Similarly, sepsis, shock and MODS developed during the stay in the ICU were commonly related to the ARF from group A to group D. A higher number of days of MODS were also documented as it progressed from group A to group D (p<0.001) (Table 4).

ARF risk factors.

| VARIABLE | GROUP A | GROUP B | GROUP C | GROUP D | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension, % | 18 (12.4) | 24 (22.0) | 15 (20.5) | 10 (30.3) | 0.053 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 21 (14.5) | 24 (22.0) | 18 (24.7) | 7 (21.2) | 0.254 |

| Hospital-acquired infection, % | 15 (10.3) | 12 (11.0) | 8 (11.0) | 5 (15.2) | 0.888 |

| Respiratory infection, % | 69 (47.6) | 56 (51.4) | 44 (60.3) | 21 (63.6) | 0.182 |

| Sepsis at the admission, % | 92 (63.4) | 90 (82.6) | 59 (80.8) | 29 (87.9) | <0.001 |

| Shock at the admission, % | 45 (31.0) | 59 (54.1) | 42 (57.5) | 19 (57.6) | <0.001 |

| MODS at the admission, % | 24 (16.6) | 52 (47.7) | 27 (37.0) | 16 (48.5) | <0.001 |

| Vasoactive before ICU, % | 20 (13.8) | 35 (32.1) | 16 (21.9) | 9 (27.3) | 0.006 |

| Nephrotoxics, number | 0.9±1.0 | 1.3±0.9 | 1.4±1.0 | 1.6±1.2 | <0.001 |

Comorbidities developed during the stay in the ICU.

| VARIABLE | GROUP A | GROUP B | GROUP C | GROUP D | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis during stay, % | 25 (17.2) | 28 (25.7) | 16 (21.9) | 22 (66.7) | <0.001 |

| Shock during stay, % | 29 (20.0) | 24 (22.0) | 21 (28.8) | 22 (66.7) | <0.001 |

| MODS during stay, % | 16 (11.0) | 21 (19.3) | 26 (35.6) | 17 (51.5) | <0.001 |

| MODS, days | 1.4±3.8 | 2.7±3.6 | 3.2±4.8 | 7.3±7.6 | <0.001 |

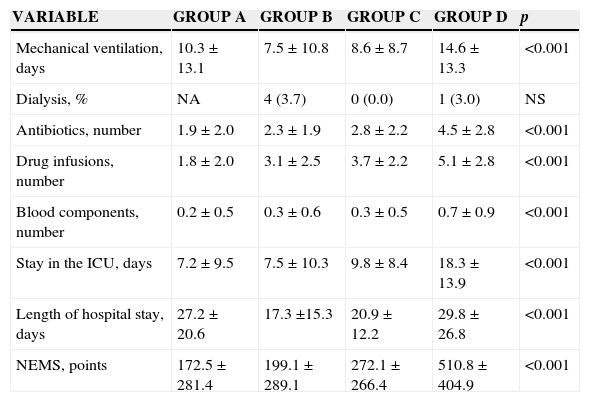

In addition, patients required a higher number of vital support elements if they had ARF on admission and then developed it in the ICU, or in case both events took place (Table 5) (p<0.001, for all the cases). This is also reflected in the length of stay in the ICU and the hospital, and the use of resources assessed by the NEMS score (p<0.001) (Table 6).

Use of resources.

| VARIABLE | GROUP A | GROUP B | GROUP C | GROUP D | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical ventilation, days | 10.3±13.1 | 7.5±10.8 | 8.6±8.7 | 14.6±13.3 | <0.001 |

| Dialysis, % | NA | 4 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.0) | NS |

| Antibiotics, number | 1.9±2.0 | 2.3±1.9 | 2.8±2.2 | 4.5±2.8 | <0.001 |

| Drug infusions, number | 1.8±2.0 | 3.1±2.5 | 3.7±2.2 | 5.1±2.8 | <0.001 |

| Blood components, number | 0.2±0.5 | 0.3±0.6 | 0.3±0.5 | 0.7±0.9 | <0.001 |

| Stay in the ICU, days | 7.2±9.5 | 7.5±10.3 | 9.8±8.4 | 18.3±13.9 | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 27.2±20.6 | 17.3 ±15.3 | 20.9±12.2 | 29.8±26.8 | <0.001 |

| NEMS, points | 172.5±281.4 | 199.1±289.1 | 272.1±266.4 | 510.8±404.9 | <0.001 |

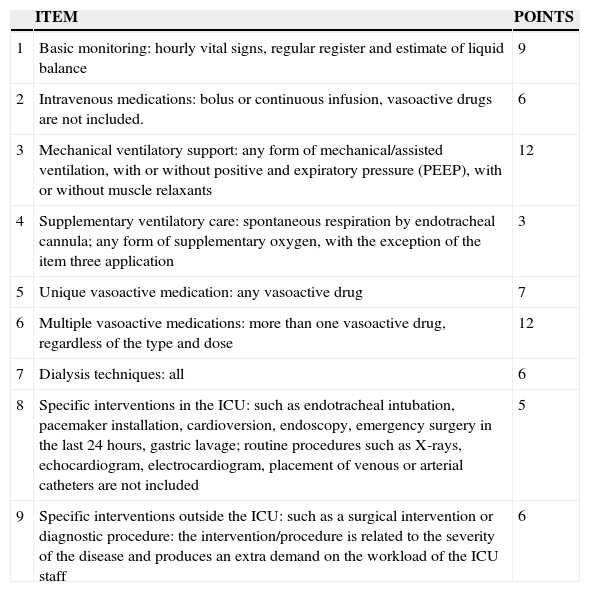

NEMS scale.

| ITEM | POINTS | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Basic monitoring: hourly vital signs, regular register and estimate of liquid balance | 9 |

| 2 | Intravenous medications: bolus or continuous infusion, vasoactive drugs are not included. | 6 |

| 3 | Mechanical ventilatory support: any form of mechanical/assisted ventilation, with or without positive and expiratory pressure (PEEP), with or without muscle relaxants | 12 |

| 4 | Supplementary ventilatory care: spontaneous respiration by endotracheal cannula; any form of supplementary oxygen, with the exception of the item three application | 3 |

| 5 | Unique vasoactive medication: any vasoactive drug | 7 |

| 6 | Multiple vasoactive medications: more than one vasoactive drug, regardless of the type and dose | 12 |

| 7 | Dialysis techniques: all | 6 |

| 8 | Specific interventions in the ICU: such as endotracheal intubation, pacemaker installation, cardioversion, endoscopy, emergency surgery in the last 24hours, gastric lavage; routine procedures such as X-rays, echocardiogram, electrocardiogram, placement of venous or arterial catheters are not included | 5 |

| 9 | Specific interventions outside the ICU: such as a surgical intervention or diagnostic procedure: the intervention/procedure is related to the severity of the disease and produces an extra demand on the workload of the ICU staff | 6 |

This is the first ARF study of Mexican critical patients that presents its incidence using the AKIN group's definition. It is also the first one to study the risk factors, medical consequences and use of resources in this population.

The ARF incidences vary according to whether it is present on admission to the ICU and then is resolved, if it is developed during the stay in the ICU or it is present on admission to the ICU, or it is resolved and then develops again and this is correlated to morbidity, mortality and the use of resources. Therefore, when performing studies of this condition, the time of presentation should be considered. Thus, in this study, the ARF was more common on admission to the ICU, then the one developed during the stay and, finally, the one present at the admission, which was resolved and then appeared again. This has already been mentioned by our group.9

The incidences reported in the three groups are found within intervals reported in literature which generally consider only the ARF developed in the ICU, reporting 10.1–69.5% rates, according to the scale used and stage.14–17

As Salgado et al. have reported, the uresis criterion is more sensitive than the creatinine criterion to define ARF, as found in this study.14

Similarly, Levi et al. reported that patients from medical areas showed more ARF cases than surgical patients. In addition, older patients were found in groups B and D, those who had ARF on admission to the ICU, regardless of whether it was resolved and developed again.16

Regarding the risk factors, the same factors as those in international literature were found.16,18 Sepsis and shock continue being the main risk factors for ARF development. At the same time, the management of these clinical conditions requires a greater use of vasoactives and drugs that turn to be nephrotoxic, favouring the persistence of renal damage, as previously reported.9

ARF development is an independent mortality predictor, increasing from 18.6% without ARF to 72.7% when two or more ARF events occur on admission and then during the stay in the ICU. However, mortality was lower than reported in the literature; it reached up to 50% in some series.14,19 In this way, the mortality attributable to ARF on admission was 11.8%, but increased to 26.1% when there were two or more ARF events from admission to the ICU.

The mechanism by which the ARF contributes to the increase in mortality is not completely understood, but the volume overload, coagulation anomalies and a greater incidence of sepsis and multiple organ failure play an important role.20–25

The use of resources evidently increases when a patient develops ARF.9 In the present study, greater use of mechanical ventilatory support, use of drug infusions, blood components and antibiotics was documented, which led to a longer stay in the ICU and the hospital. The measurement of the use of resources through the NEMS scale showed an output greater than double in the presence of ARF. The NEMS scale is equivalent to the Therapeutic Intervention Score System (TISS) and its usefulness is to classify patients into 4 classes to assign nurses to: Class I <10 points, patients who do not need UTI; Class II 10–19 points, 1:2 nurse–patient relation; Class III 20–39 points, 1:1 nurse–patient relation; and Class IV ≥40 points, 2:1 relation, two nurses per patient.26

Study limitations. The nature of a unique centre limits generalisation, and the design of a relatively small cohort does not allow the assessment of other contributory factors of prognostic importance.

However, the present study characterises the incidence, risk factors and impact on the ARF regarding health, life and use of resources, using the most recent standardised definition which simultaneously uses the serum creatinine and urinary output criteria.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare not to have any conflict of interest in the elaboration of this work.