We analyzed the distribution and diversity patterns of ground dwelling spiders in the main plant associations of the protected area known as Churince, in the Cuatro Ciénegas Basin, Coahuila, Mexico. Spiders were collected with pitfall ramp traps during the years 2011 and 2012. We found 29 families and 144 morpho-species. The most abundant families were Gnaphosidae, Lycosidae and Salticidae. The most common species were Gnaphosa sp. and G. hirsutipes. There were 4 new records for Mexico and 4 for the Chihuahuan Desert, including 2 possible new species of Sergiolus and Oecobius. The number of species was high in comparison when compared with other studies in the Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts. The species abundances were fitted to the Fisher distribution. The rarefied richness was highest at sites with denser vegetation and high humidity. Dominance was high and richness low in sparsely vegetated sites. The wandering hunters were dominant in all sites, but the guild diversity was higher in sites with high plant complexity

Se analizaron los patrones de distribución y diversidad de arañas que habitan el suelo en los principales tipos de vegetación del área protegida conocida como Churince, en el valle de Cuatro Ciénegas, Coahuila, México. Las arañas fueron recolectadas durante los años 2011 y 2012 usando trampas de caída de tipo rampa. Se encontraron 29 familias y 144 morfo-especies. Las familias más abundantes fueron Gnaphosidae, Lycosidae y Salticidae. Las especies más comunes fueron Gnaphosa sp. y G. hirsutipes. Se obtuvieron 4 registros nuevos para México y 4 para el desierto chihuahuense, incluyendo 2 posibles especies nuevas de los géneros Sergiolus y Oecobius. El número de especies fue alto en comparación con lo documentado en otros sitios de los desiertos chihuahuense y sonorense. La abundancia de las especies se ajustó a la distribución de Fisher. La riqueza rarefaccionada fue más alta en los sitios con mayor densidad de vegetación y con mayor humedad. La dominancia fue más alta y la riqueza más baja en sitios sin vegetación o con vegetación escasa. El gremio de las cazadoras errantes fue el más numeroso en todos los sitios, pero la diversidad de gremios fue mayor en sitios en donde la complejidad vegetal fue mayor.

Spiders are known to respond to a wide variety of environmental conditions and can be indicators of plant associations and habitat perturbations (Cardoso, Silva, Oliveira, & Serrano, 2004; Wheater, Cullen, & Bell, 2000). In spite of their high diversity and the fact that they are the main insect and other terrestrial arthropod predators (Polis & Yamashita, 1991; Turnbull, 1973), there are only very few studies of spider communities in arid environments of North America (e. g. Broussard & Horner, 2006; Gertsch & Riechert, 1976; Lightfoot, Brantley, & Allen, 2008; Muma, 1975; Richman, Brantley, Hu, & Whitehouse, 2011; Sánchez & Parmenter, 2002). Spider communities have been studied in scrubland vegetation and oases in the south of the Peninsula of Baja California (Jiménez, 1988; Jiménez & Navarrete, 2010; Llinas-Gutiérrez & Jiménez, 2004) but, to date, there are few studies in the Chihuahuan Desert and none in the portion of this ecoregion corresponding to the north of Mexico.

The Chihuahuan Desert includes the largest arid and semi-arid region in Mexico. Due to its topography and habitat diversity, it has a high number of species that includes birds (Contreras-Balderas, López-Soto, & Torres-Ayala, 2004), reptiles and amphibians (Mendoza-Quijano, Arturo, Liner, & Bryson Jr., 2006) and arthorpods such as scorpions and thrips. These 2 arthropod groups also have a number of endemic species in the basin (Sissom & Hendrixson, 2006; Williams, 1968; Zúñiga-Sámano, Johansen-Naime, García-Martínez, Retana-Salazar, & Sánchez-Valdez, 2012). There are no studies on the composition, diversity or distribution of spider species in Cuatro Ciénegas. However, the New Mexico Museum of Southwestern Biology collected and published a general report on arthropods where 24 spider families were recorded from various localities and substrates of the Cuatro Ciénegas Basin (Division of Arthropods and Natural Heritage of the New Mexico Museum of Southwestern Biology Biology Department, 2010).

The Valley of Cuatro Ciénegas is located in the Chihuahuan Desert. Given the high levels of endemism and species biodiversity, 85,000 hectares have been designated as a flora and fauna protected area by the federal government (Gómez-Pompa & Dirzo, 1995) and it is an internationally important wetland included in the Ramsar convention list. It is also among the Priority Eco-regions for Conservation according to the World Wildlife Fund (Souza et al., 2006).

The diversity of some groups, including bacteria, vertebrates and plants in Cuatro Ciénegas is well known and one of the aims of this study was to present the first results on spider diversity in the area. Additionally, we assessed the spider distribution in the main vegetation types in order to respond to the following basic questions: 1) How many species are there and what is the species abundance distribution pattern? 2) How do richness and dominance vary between vegetation types? 3) Which species are associated with any of the main types of vegetation? and 4) How does the guild proportion vary between plant communities?

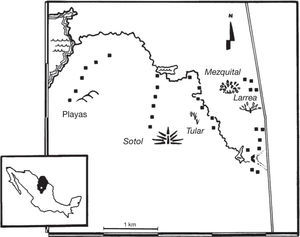

Materials and methodsStudy areaThe Valley of Cuatro Ciénegas, Coahuila, Mexico is located between 26°45’00”-27°00’00”N, 101°48’49”-102°17’53” W, at an altitude of 740 m asl. It is an enclosed watershed surrounded by high mountains (>3,100 m). Annual precipitation is ≈150mm. The mean temperatures of the warmest and coldest months are 28.5 °C and 14.5 °C respectively. The valley hosts a large system of natural springs, streams and ponds of great interest for scientific research.

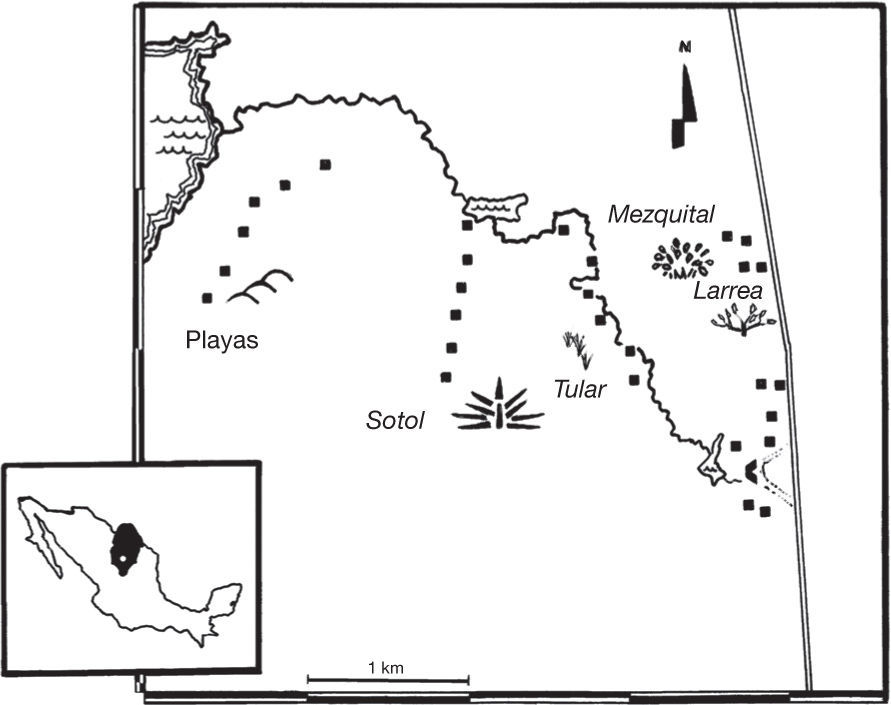

VegetationThe spiders were collected in the 5 main vegetation associations of the locality known as Churince: 1) mezquite shrubland (mezquital) where Prosopis glandulosa is dominant, 2) wet grassland where Sporobolus sp. and Distichlis spicata are the dominant species (tular), 3) small-leaved desert scrub dominated by Larrea tridentata and Fouqueria splendens (larrea), 4) Dasylirion wheeleri desert scrub (sotol), and 5) areas lacking vegetation near the main water body in the area (playas). The Churince area is c. 2,000 ha (Fig. 1). We used a 2 m pole to estimate the vegetation density of grasses, shrubs, cacti, and desert spoon or common sotol. The method consists of placing the pole in a perpendicular position from the ground and to record any plant contact (Corcuera, Jiménez, & Valverde, 2008; McNett & Rypstra, 2000). We registered the number of contacts at 0-1 m and >1 m. This procedure was repeated each meter –50 m– in 5 linear transects in each plant association. The distance between transects was 100 m. Since more than 1 contact could be made in a single point, density values could be >200. The density of grasses, sotol shrubs and cacti was the sum of the number of contacts with the stick for each group. We also measured the number of contacts with no vegetation. The percentage of soil humidity from each site was measured by means of a gravimetric analysis. For this purpose, 5 samples of 100g of fresh soil were weighed in each site. These were then dried in an 80 °C furnace until a constant weight was obtained, and once dried, the weight was measured again. Moisture percentage was the difference between the 2 measurements. An average of the results of the 5 replicas for each site was calculated.

SpidersSpiders were caught weekly from March to May and from September to November 2011 and from January to May and July to October 2012. Six replicates (sample units) of 5 traps each were placed in each vegetation association separated by 100 m. Two of these replicates were lost in mezquital and larrea (the final sampling effort therefore consisted of 26 sample units and 130 traps altogether). We removed the traps between collecting periods, but these were placed in the same locations when sampling again. The 5 traps in each sample unit site were placed in the center and extreme ends of a 10 × 10 m quadrat. Each trap consisted of a plastic recipient (15 × 23 × 8cm) with two 6 × 6cm lateral openings. A triangular aluminum ramp was placed in the lower part of each opening (Bouchard, Wheeler, & Goulet, 2000). Each ramp was previously varnished with a sand texture aerosol. The recipients were filled with water and a small quantity of detergent added to lower the surface tension. It has been shown that these traps are efficient to assess spider communities (Brennan, Majer, & Reyhaert, 1999; Pearce et al., 2005).

All the adults and juveniles were determined to species level or morphospecies. Specimens were identified to the family and genus levels according to Ubick et al., 2005 id="bib0225"Ubick, Paquin, Cushing, & Roth (2005) and, when possible, to the species level with the taxonomic works of various authors. Scientific names were checked in the World spider catalogue (2014). Each species was assigned to a guild following Cardoso, Pekár, Jocque, and Coddington (2011). These authors considered foraging strategy (type of web and hunting method), prey range (stenophagous or euryphagous), vertical stratification (ground or foliage) and circadian activity (diurnal or nocturnal). We used this classification because it takes a global approach and considers earlier guild groupings undertaken by others.

The specimens were preserved in 75% ethanol and deposited in the Arachnological Collection (CARCIB) at the Center for Biological Research of the Northwest, La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico.

Statistical analysesWe tested the theoretical and the observed distribution of spider abundances with a chi-square goodness-of-fit test.

Since sample sizes were different, we used rarefaction analyses to compare the number of species between sites (James & Rathbun, 1981). The first order Jacknife estimator was used to evaluate the sampling efficiency. This estimator can give a reasonable estimate when the number of samples is small (González-Oreja, de la Fuente-Díaz Ordaz, Hernández-Santín, Buzo-Franco, & Bonache-Regidor, 2011). This analysis was done with EstimateS v. 8.0 (Colwell, 2006).

Dominance was calculated with the Simpson's diversity index (Magurran, 2004). In order to visually compare the abundance patterns of species between the different types of vegetation, rank-abundance curves were elaborated (James & Rathbun, 1981). The species distribution was analyzed with a correspondence analysis using MVSP v. 3.1 (Kovach, 1999). We used the abundance of each species but eliminated those species with less than 3 individuals from the analysis since very low numbers may result from random catches.

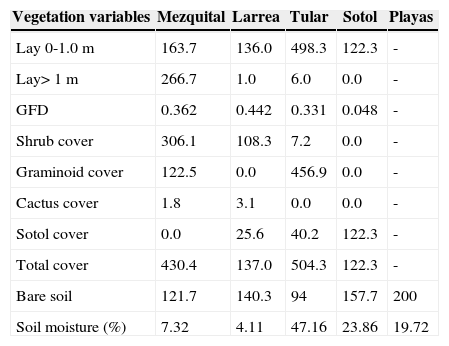

ResultsHabitat variablesThe mezquite shrubland had the highest vegetation density in the >1 m layer. The diversity of plant growth life forms was also relatively high. It was the only site with trees and had the highest shrub cover. Soil humidity was low because the soil is compact in comparison to the other sites and it does not allow for very much water accumulation (Table 1). The larrea site had the highest diversity of growth forms and the lowest content of soil moisture. Vegetation cover was relatively low and the soil was also compact in this site. The tular grassland had the highest vegetation cover and soil humidity. The Dasylirion desert scrub (sotol) had relatively high soil moisture but the vegetation cover was low. The high dominance of D. whelleri is reflected in the low growth form diversity. The site with bare soil or playas outlined a body of water. It had no plant cover and the soil moisture was intermediate compared to the other sites (Table 1).

Plant density at 2 heights (lay 0-1.0= vegetation density from 0 to 1 m; lay> 2= vegetation density above 1 m height) as well as the cover of shrubs, graminoids (grasses, sedges and rushes), sotol and cactus in 5 plant associations in the region of Churince, Cuatro Cienegas, Coahuila, Mexico. The units refer to the number of contacts with a graduated pole (see methodology). Bare soil is the number of points with no vegetation. The total number of points was 200 but in each point there could be more than 1 plant contacts. GFD is the diversity (ShannonWiener) of growth forms. The percentage of soil moisture is also shown

| Vegetation variables | Mezquital | Larrea | Tular | Sotol | Playas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lay 0-1.0 m | 163.7 | 136.0 | 498.3 | 122.3 | - |

| Lay> 1 m | 266.7 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 0.0 | - |

| GFD | 0.362 | 0.442 | 0.331 | 0.048 | - |

| Shrub cover | 306.1 | 108.3 | 7.2 | 0.0 | - |

| Graminoid cover | 122.5 | 0.0 | 456.9 | 0.0 | - |

| Cactus cover | 1.8 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - |

| Sotol cover | 0.0 | 25.6 | 40.2 | 122.3 | - |

| Total cover | 430.4 | 137.0 | 504.3 | 122.3 | - |

| Bare soil | 121.7 | 140.3 | 94 | 157.7 | 200 |

| Soil moisture (%) | 7.32 | 4.11 | 47.16 | 23.86 | 19.72 |

A total of 701 spider specimens were caught. These were grouped in 144 morphospecies, 105 genera and 29 families (Appendix). Half of the individuals (50.6%) were adults (10.98% females and 39.6% males, and 49.4% immature). Four species were new records for Mexico (Dictyna agressa Ivie, 1974 (Dictynidae), Trachyzelotes lyonneti (Audouin, 1826) (Gnaphosidae), Haplodrassus dixiensis Chamberlin and Woodbury, 1929 (Gnaphosidae) and Apollophanes texanus (Banks, 1904) (Philodromidae), and 3 unidentified species for the Chihuahuan Desert (Paratheuma sp. (Desidae) 1 species of the Leptonetidae and 1 of Pisauridae). We also found 2 possible new species of Sergiolus (Gnaphosidae) and Oecobius (Oecobiidae).

The most abundant family was Gnaphosidae (49.3%), followed by Lycosidae (15.1%), Salticidae (11.5%), Philodromidae (5.5%), Dictynidae (4.2%), Thomisidae (3.4%) and Araneidae (3%). Gnaphosidae had the highest number of species (38), followed by Lycosidae (22), Salticidae (20), Thomisidae (9), Philodromidae (8), Araneidae and Dictynidae (both 5). The most abundant species were G. hirsutipes and Gnaphosa sp. (Gnaphosidae) (17% of the total), 1 unidentified species of Pardosa (Lycosidae) (6%), Haplodrassus dixiensis (Gnaphosidae) (5%), Habronattus sp. (Salticidae) (4%), Calillepis sp. (Gnaphosidae) and Gnaphosa salsa (Gnaphosidae) (each one representing 3.5% of the total catch). Most species were rare with 105 species represented by ≤ 3 individuals and 74 species with only 1 individual.

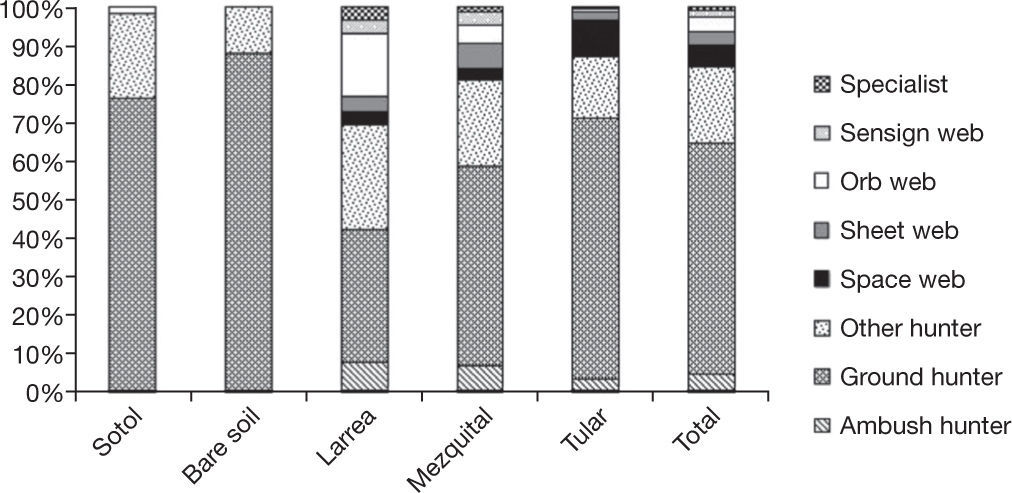

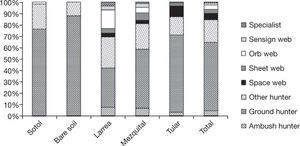

Spiders were grouped in 8 guilds following Cardoso et al. (2011): ambush hunters (Sicariidae and Thomisidae), ground hunters (Corinnidae, Gnaphosidae, Liocranidae, Lycosidae, Oonopidae, Zorocratidae), other hunters (Anyphaenidae, Miturgidae, Philodromidae, Salticidae, Scytodidae, Clubionidae, Oxyopidae), space web weavers (Dictynidae, Diguetidae, Leptonetidae, Nesticidae, Theridiidae), sheet web weavers (Linyphiidae, Pisauridae, Desidae, Dipluridae), orb web weavers (Araneidae), sensing web weavers (Cyrtauchenidae, Filistatidae, Oecobiidae) and specialist spiders (Caponiidae) (Appendix). The families from the other hunter guild have been included by other authors as aerial hunters/runners. They are typically found on plant structures (foliage, trunks or branches) (Dias, Carvalho, Bonaldo, & Brescovit, 2009). Ground hunters and other hunting spiders were represented by the largest number of individuals in all sites (60.6% and 18.4%). Specialists and sensing web weavers were only represented by 1.1% and 1% respectively. We only found individuals of these 2 groups in the playas site. In the rest of the sites, especially in mezquital and larrea, other guilds were present in relatively high proportions (Fig. 2).

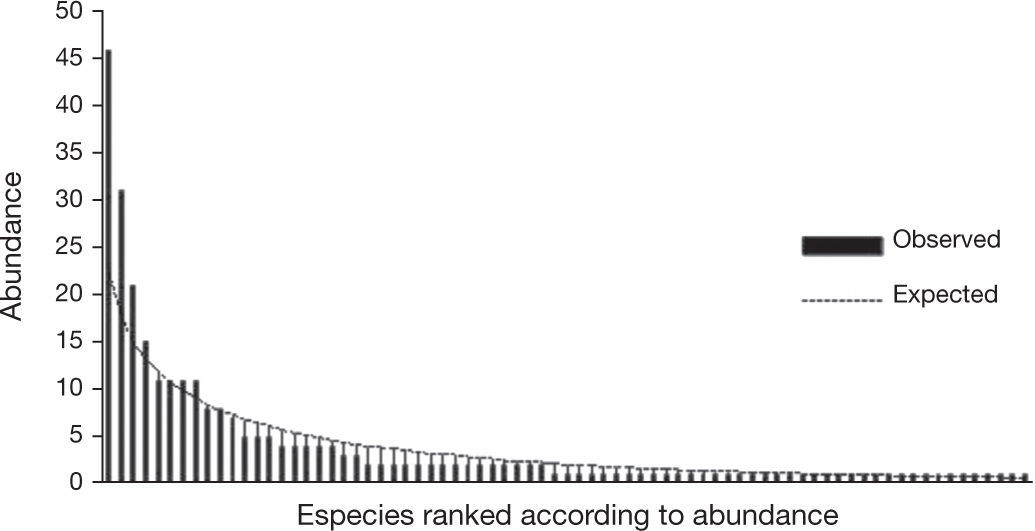

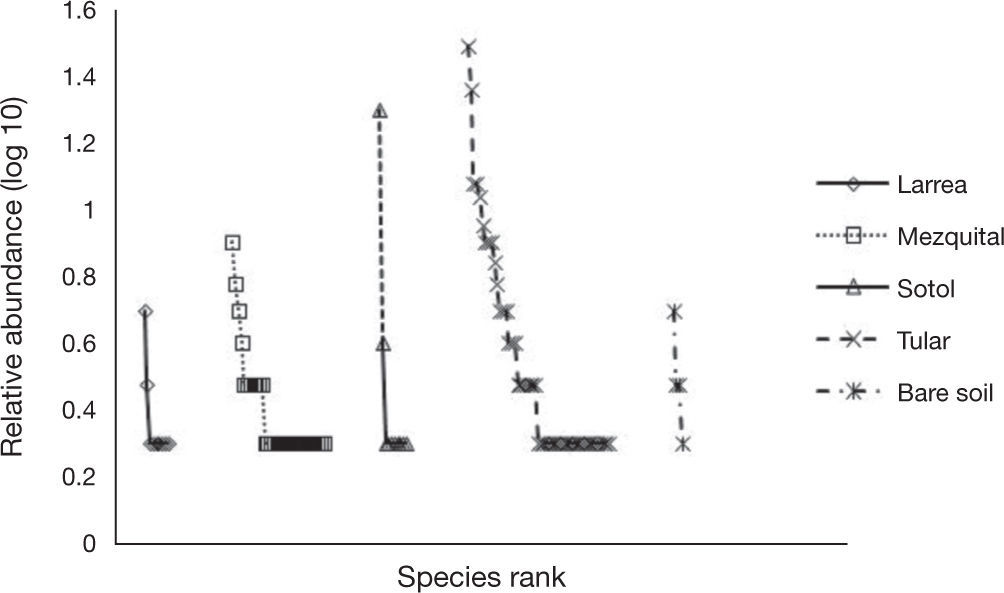

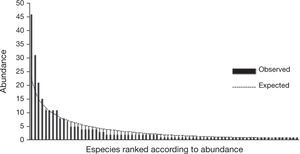

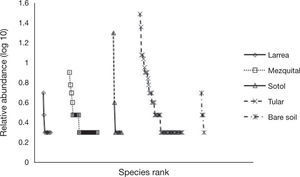

Relative abundancesThe distribution of the species abundances was adjusted to Fisher's logarithmic series (a few abundant species and many rare species) (McGill, 2011) with α= 33.5 and x= 0.893 (Fig. 3). The difference between the expected distribution and the one observed was not significant (χ2= 44.97, 75gg. l., p> 0.05).

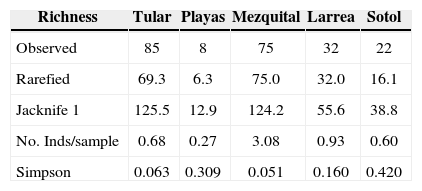

Species richness and dominance between sitesAccording to the Jacknife estimator 64% of the ground dwelling spiders were collected in the region, and an average of 62% for each vegetation type (Table 2). The rarefied richness was higher in mezquital and tular (Table 2). The 2 vegetation layers (0-1 m and >1 m) were well represented in the first site, but the second one presented a higher density of the 0-1 m as well as a higher percentage of soil moisture (Table 1). The lowest number of species and individuals was found in the playas site (Table 2).

Observed and rarefied species richness as well as expected number of species according to the Jacknife 1 estimator in 5 plant associations in Cuatro Cienegas, Coahuila, Mexico. Spider abundance and dominance (Simpson Index) are also included

| Richness | Tular | Playas | Mezquital | Larrea | Sotol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | 85 | 8 | 75 | 32 | 22 |

| Rarefied | 69.3 | 6.3 | 75.0 | 32.0 | 16.1 |

| Jacknife 1 | 125.5 | 12.9 | 124.2 | 55.6 | 38.8 |

| No. Inds/sample | 0.68 | 0.27 | 3.08 | 0.93 | 0.60 |

| Simpson | 0.063 | 0.309 | 0.051 | 0.160 | 0.420 |

The rank-abundance curves show that dominance was higher and equitability lower in the 2 sites with less vegetation (sotol and playas) (Fig. 4). This was confirmed by the Simpson index (Table 2).

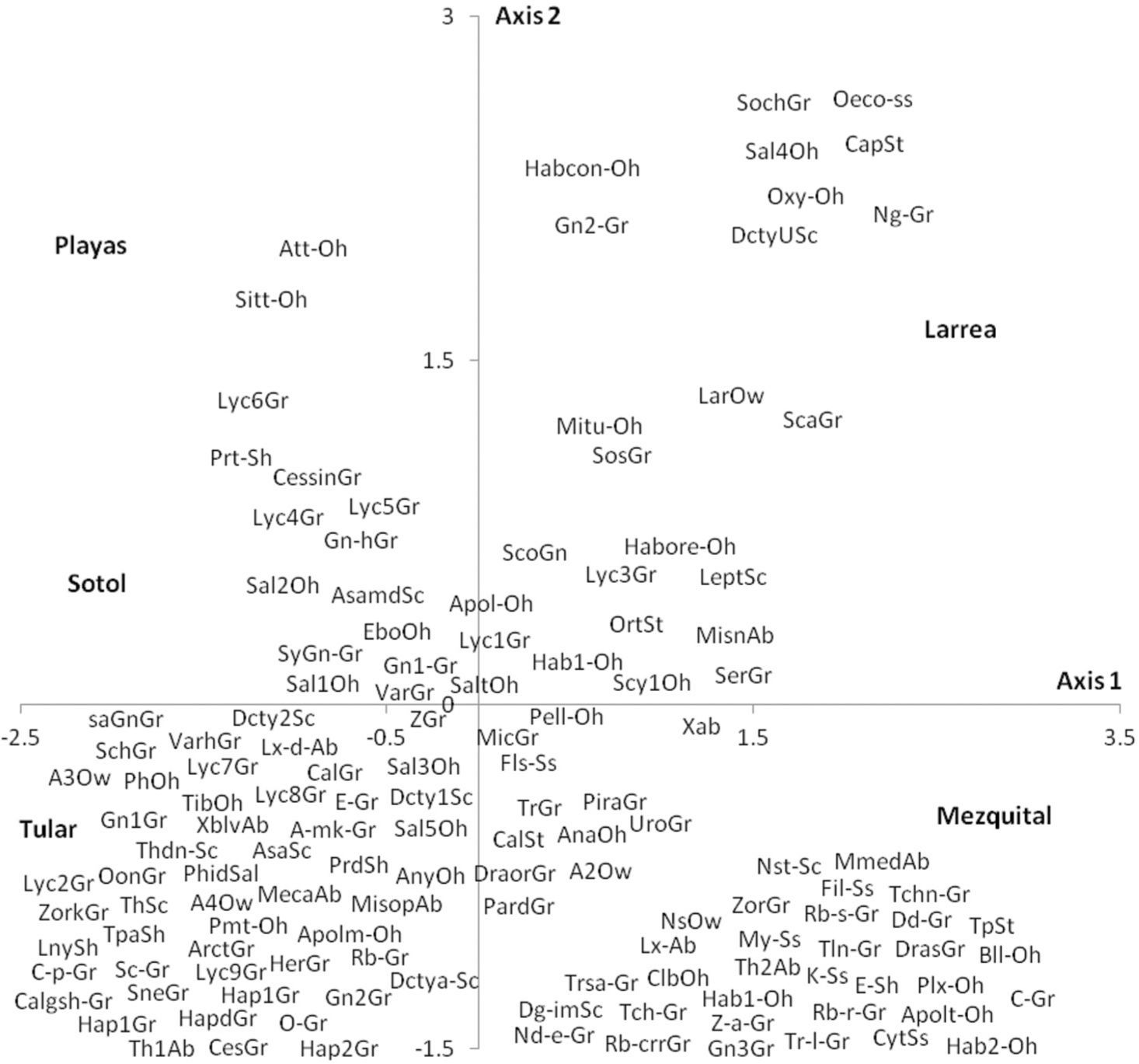

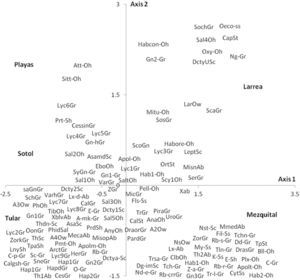

Species distributionThe spider species distribution was examined by means of a correspondence analysis. The first axis (eigenvalue= 0.461) of the ordination explained 32% of the variation. The second axis (eigenvalue= 0.398) explained a further 27.7%. The results of the correspondence analysis show that the 2 sites with less vegetation (playas and sotol) lacked many of the guilds found elsewhere and mainly had species of Gnaphosidae and Lycosidae. The difference between these 2 sites is that in the sotol area, species from Salticidae were also found (Fig. 5). Even though mezquital and larrea shared several species, most species from the former belonged to the ground hunter guild (i. e. Gnaphosidae and Lycosidae); in larrea, on the other hand, the species present belonged to various guilds (ambushers, other hunters, and orb, sensing web and space web weavers). Drassyllus orgilus, Zorocrates karli, and an unidentified species of Gnaphosidae were exclusive to the mezquite shrubland. We found 14 unique species in tular: 2 species of Dictynidae, 1 Gnaphosidae (Callilepis gertschi), 5 species of Lycosidae (Varacosa hoffmannae and 4 others), 1 Philodromidae, 2 Salticidae (Asagena medialis and Phidippus sp.), 2 Thomisidae (Misumenops and another one which was not identified) and 1 Theridiidae (Fig. 5).

DiscussionLocally, the species abundance distribution of the Churince region follows a pattern that is common when few environmental variables determine the species population density (May, 1975), as is the case of temperature and dryness in desert areas (Granados-Sánchez, Hernández-García, & López-Ríos, 2012; Louw & Seely, 1982). This pattern seems to be similar in the arid communities of Baja California and other North American deserts (Jiménez & Navarrete, 2010; Richman et al., 2011).

We found many more males than females (10.98% females and 39.6% males, 49.35% juveniles). Since most spiders were wandering males, perhaps they were seeking out females living in galleries or webs that tended to be more sessile. These would increase the likelihood of capturing more males in the type of traps we used in the study (Agnew & Smith, 1989).

Compared to other studies conducted in different regions of the Great Basin, Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts in North American, Cuatro Ciénegas has a higher number of families and species. Hatley and MacMahon (1980), for example, found 40 species from 11 families from 4,613 specimens in Lake Bonneville, in the Great Basin Desert, USA, while Llinas-Gutiérrez and Jiménez (2004) found 61 species from 22 families in an oasis in the Sonoran Desert of Baja California Sur, Mexico. Later Jiménez and Navarrete (2010) reported 52 species from 22 families of ground spiders in the sarcocaule shrubland in the same region. Broussard and Horner (2006) published a list of 66 species and 24 families in the region of Trans-Pecos, Texas, in the Chihuahuan Desert. In a 30 year study, Richman et al. (2011) found 117 species of 24 families in Jornada del Muerto, Nuevo Mexico. This site is also part of the Chihuahuan Desert. The authors compared their study area with White Sands, Nuevo Mexico, where 39 species and 14 families were collected, and with Valley of Fire in the Mohave Desert in Nevada, where 91 species and 23 families were found. With the exception of White Sands and the Baja California wetlands, Gnaphosidae and Salticidae had the higher richness in all deserts. White Sands consists of loose gypsum dunes and therefore the ground conditions are very different from the other sites mentioned here. Comparatively, this site had the lower number of species which may be explained by the soil conditions and lack of vegetation. Proportionally, the Baja California wetlands had the lowest number of Gnaphosidae species and the highest of Araneidae (10 species followed by 6 in Jornada del Muerto and 5 in Churince). This is mainly because direct sampling from the vegetation was used in this site. Dictynidae was the second richest family in White Sands (6 species). This is surprising because most species of the family are arboreal and make webs on foliage. This may explain why they were trapped in the 2 sites with more vegetation in Churince (tular and mezquital). On the other hand, members of the cribellate species of the genus are troglobites and live below ground level (Ubick & Richman, 2005) and therefore the local place and substrate where they were collected could explain their presence in White Sands. The other relatively common families in the studies mentioned above where Theridiidae, Thomisidae and Philodromidae and, in particular for Churince, the wolf spiders.

Several wolf spiders species are well adapted to the arid environments (Russell-Smith, 2002); however, none of the mentioned studies has documented as many species as those found in this study. There are 39 species/morphospecies of this family in the Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts (9 species in Jornada del Muerto, 2 in White Sands, 5 in Valley of Fire, 6 in the Big Bend, 4 in Baja California wetlands, 2 in Comitán a Baja California scrubland and 23 in Churince) (Jiménez & Navarrete, 2010; Llinas-Gutiérrez & Jiménez, 2004; Richman et al., 2011). It appears that each site has its own wolf spider assembly since, for instance, only 1 species, Camptostoma parallela, has been found in Churince and one other location (Jornada del Muerto). The same is true for the other species. The wetlands from Baja California Sur do not share any species with the other sites and only Hogna coloradensis was found in more than 2 locations, Jornada del Muerto, Valley of Fire and White Sands. The fact that few species are shared among deserts suggests that the random assembly rules may be true for these communities (Weiher & Keddy, 1999). The high number of lycosids and other species in Churince may be due to the presence of the different vegetation associations and moisture conditions which have been colonized by several genera which include diurnal and nocturnal species. Camptocosa species, for example, are nocturnal (Dondale, Jiménez, & Nieto, 2005), Arctosa are fossorial and nocturnal (Jiménez pers. obs.) while Pirata and Pardosa are diurnal and cursorial, (Correa-Ramírez, Jiménez, & García-De León, 2010; Wallace & Exline, 1978). The coexistence of the similar species may result from the resource partitioning resulting from a variety of habits.

The numerically dominant species in other deserts of North America belong to the families Miturgidae (Syspira tigrina) in Baja California (Jiménez & Navarrete, 2010), Oxyopidae and Philodromidae (Oxyopes tridens and Tibellus chamberliini respectively) in Jornada del Muerto and Lycosidae and Gnaphosidae (Pardosa sp. and Callilepis gerschi respectively) in the Big Bend. In the case of Cuatro Ciénegas, the dominant species were G. hirsutipes and Gnaphosa sp.1 (Gnaphosidae) and Pardosa sp. (Lycosidae). Gnaphosa hirsutipes in particular, has been captured in riparian vegetation (Platnick & Shadab, 1975). In this study, it was one of the most abundant species in all sites of Cuatro Ciénegas, but it was particularly abundant in the more humid or shaded environments, such as tular and mezquital. Similarly, species of Pardosa, also common in these 2 sites, are associated with humid areas or water bodies (Punzo & Farmer, 2006).

The rarefied number of species was larger and dominance was lower in mezquital (the site that presents the higher density of the >1 m vegetation layer) and tular (which had the highest vegetation density in the 0-1 m layer, and higher soil humidity) (Table 2). The larrea site was on rocky ground and had the greater diversity of plant growth forms (Table 1). This would suggest that this plant association would present a higher number of microhabitats in comparison to the others but the number of species found here was lower than that in the 2 sites mentioned above. The low humidity and poor shade conditions may reflect the low spider diversity. Other studies have found that spider richness and abundance is related to shade and humidity (Jiménez & Navarrete, 2010; Polis & Yamashita, 1991).

The higher dominance in playas and sotol (Table 2, Fig. 4) could be due to the uncompacted sandy soil where only a few plants, such as D. wheeleri can grow. Together with the bare soil site (playas), the sotol area is more exposed to wind and temperature fluctuations than the other sites and few tolerant spider species can achieve relatively high densities in these conditions. Gnaphosidae is one of the most diverse families in deserts around the world (Polis & Yamashita, 1991), and the genus Gnaphosa is common in other arid regions in North America. The dominant species in both sites were Gnaphosa sp.1 and G. salsa. Together with Ebo sp. (Philodromidae), they were the only species present in all locations. This suggests that they are tolerant to arid environments.

Some species of Habronattus (Salticidae) are typical of arid environments (Griswold, 1987) and in this study Habronattus sp. 1 was one of the most abundant species. Other species, such as Habronattus oregonensis is widely distributed in the United States and Canada in a wide variety of microenvironments which indicates that it is also tolerant to harsh conditions (Griswold, 1987). As well, H. oregonensis, the dominant species in the sites with more vegetation belonged to the Lycosidae (Pardosa sp.), Pisauridae, Araneidae (Larina sp.) families. With the exception of Larinia sp., represented by a single individual in sotol, these species were absent in the more exposed sites.

Out of the 29 families, only 5 were found in the playas and 6 in the sotol sites, while 14, 19 and 20 were found in larrea, tular and mezquital (Appendix). The family Araneidae was well represented in the larrea site since this is where the vegetation architecture is suitable for orb weavers (Cloudsley-Thompson, 1983). Larinia sp. was also abundant in the larrea site.

The type of traps we used capture more individuals of ground hunters than individuals from other guilds but sensing web (Cyrtaucheniidae, Filistatidae), specialists (Caponiidae), sheet web weavers (Desidae and Linyphiidae), some web weavers (Dictynidae) and some other hunters of Philodromidae and Salticidae and ambushers of Thomisidae live in low vegetation and/or on the ground and are also amenable to be caught with ramp traps. It is therefore possible to compare the proportions of each of these guilds between sites. The most diverse guild in desert regions all around the world is the ground hunting group (Cloudsley-Thompson, 1983; Polis & Yamashita, 1991; Taucare-Ríos, 2012). In this study, this guild represented 60% of the individuals caught and 60% of the number of species. Nonetheless, when comparing sites, 88% of the abundance and 63% of the species richness of this guild were found in bare soil while the percentages in the sites with greater vegetal diversity were considerably lower (35% and 44% in larrea and 52% and 43% in the mezquital site) (Fig. 2). This result was expected because sites with a higher vegetation density and complexity have more microhabitats available for species from different guilds. In this particular case, the diversity of growth forms was directly associated with the diversity of guilds (r= 0.96, p= 0.0085). The correspondence analysis showed the relationship between the sites and the species present in each one of them (Fig. 5). It also confirmed that the species present in larrea and mezquital belong to various guilds. The number of species of different guilds was not as high in tular, but this site had the highest number of unique species (41 species in comparison with 34 in the mezquital, and only 2 in the sotol and playas). This final result indicates that both, vegetation and humidity, offer conditions where the species can find shelter in desert environments (Llinas-Gutiérrez & Jiménez, 2004).

Even when the number of individuals captured in 2 years of sampling was low, a large number of species was found compared to those recorded for other locations in the Chihuahuan and Sonora deserts. The strikingly different plant associations and soil types with different structure and humidity content result in a wide variety of microhabitats that could partly explain the high number of species. The low abundances could be due to meteorological fluctuations throughout the year that cause population ecological crunches (Wiens, 1977). This could also explain the coexistence of ecologically similar species (Wiens, 1977), represented by ground hunters in particular. In addition, the high concentrations of carbonates, sulfates and gypsum in the soil limit the growth of vegetation and possibly the availability of prey.

AcknowledgementsWe want to express our gratitude to Dr. Valeria Souza from the Instituto de Ecología, UNAM, for her help in developing this project. We are also very thankful to our professors César Hernández, Martha Elsa Castro, Patricia Lorena Arizpe, Juan Pablo Ayala, to the students from the Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Agropecuario No. 22 Venustiano Carranza in Cuatro Ciénegas, and to Juan Biviano García Luján and Jesús Ángel Bravo Villa, for their collaboration with the fieldwork. YBF acknowledges the scholarship granted by the Conacyt. We thank the reviewers and the associated editor for the comments and suggestions that improved our work. Specimens were collected with permit SGPA/DGVS FAUT-0230 granted by the Undersecretary management for environmental protection.

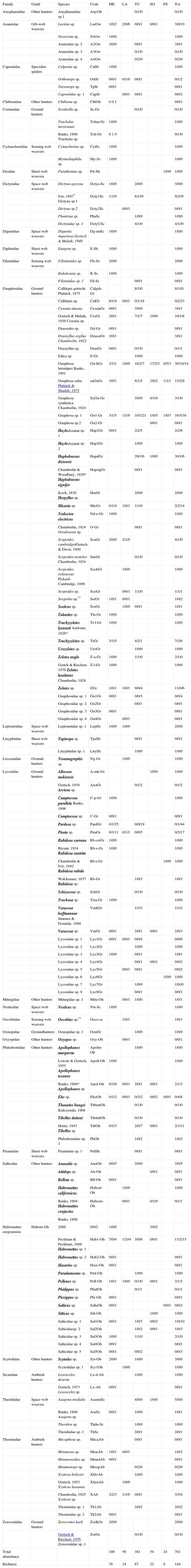

Spider species and guilds found in the main vegetation types in the region of Churince, Cuatro Ciénegas. (*) new recorded for Mexico, (**) possible new species. SO: stool; PS: playas; LA: Larrea; ME: mezquital; TU: tular. Number of males, females and juveniles are included (i.e. 5/2/0 means that there were 5 males, 2 females and zero juveniles for a particular species in a particular site)

| Family | Guild | Species | Code | ME | LA | TU | SO | PS | Tot |

| Anyphaenidae | Other hunters | Anyphaenidae sp.1 | AnyOh | 0/1/0 | 0/1/0 | ||||

| Araneidae | Orb-web weavers | Larinia sp. | LarOw | 1/0/2 | 2/0/6 | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | 3/0/10 | |

| Neoscona sp. | NsOw | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Araneidae sp. 2 | A2Ow | 3/0/0 | 0/0/1 | 3/0/1 | |||||

| Araneidae sp. 3 | A3Ow | 0/1/0 | 0/1/0 | ||||||

| Araneidae sp. 4 | A4Ow | 0/2/0 | 0/2/0 | ||||||

| Caponiidae | Specialist spiders | Calponia sp. | CalSt | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||

| Orthonops sp. | OrtSt | 0/0/1 | 0/1/0 | 0/0/1 | 0/1/2 | ||||

| Tarsonops sp. | TpSt | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Caponiidae sp. 1 | CapSt | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | 0/0/2 | |||||

| Clubionidae | Other hunters | Clubiona sp. | ClbOh | 0 0 1 | 0/0/1 | ||||

| Corinnidae | Ground hunters | Scotinella sp. | Sc-Gr | 0/1/0 | 0/1/0 | ||||

| Trachelas mexicanus | Tchm-Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Banks, 1898 Trachelas sp. | Tch-Gr | 0 1 0 | 0/1/0 | ||||||

| Cyrtaucheniidae | Sensing web weavers | Cytauchenius sp. | CytSs | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||

| Myrmekiaphila sp. | My-Ss | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Desidae | Sheet web weavers | Paratheuma sp. | Prt-Sh | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||

| Dictynidae | Space web weavers | Dictyna agressa | Dctya-Sc | 1/0/0 | 2/0/0 | 3/0/0 | |||

| Ivie, 1947* Dictyna sp.1 | Dcty1Sc | 1/1/0 | 8/1//9 | 9/2//9 | |||||

| Dictyna sp.2 | Dcty2Sc | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Phantyna sp. | PhaSc | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Dictynidae sp. 1 | DctyUSc | 4/1/0 | 4/1//0 | ||||||

| Diguetidae | Space web weavers | Diguetia imperiosa Gertsch & Mulaik, 1940 | Dg-imSc | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||

| Dipluridae | Sheet web weavers | Euagrus sp. | E-Sh | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||

| Filistatidae | Sensing web weavers | Filistatoides sp. | Fls-Ss | 2/0/0 | 2/0/0 | ||||

| Kukulcania sp. | K-Ss | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Filistatidae sp. 1 | Fil-Ss | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Gnaphosidae | Ground hunters | Callilepis gertschi Platnick, 1975 | Calgsh-Gr | 8/1/0 | 8/1//0 | ||||

| Callilepis sp. | CalGr | 0/1/4 | 0/0/1 | 0/1/18 | 0/2/23 | ||||

| Cesonia sincera | CessinGr | 0/0/1 | 3/0/0 | 3/0/1 | |||||

| Gertsch & Mulaik, 1936 Cesonia sp. | CesGr | 2/0/1 | 7/1/7 | 1/0/0 | 10/1/8 | ||||

| Drassodes sp. | Dd-Gr | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Drassyllus orgilus Chamberlin, 1922 | DrasorGr | 3/0/1 | 3/0/1 | ||||||

| Drassyllus sp. | DrasGr | 0/0/1 | 0/1/0 | 0/1/1 | |||||

| Eilica sp. | E-Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Gnaphosa hirsutipes Banks, 1901 | Gn-hGr | 2/1/1 | 1/0/0 | 16/2/7 | 17/2/3 | 0/5/3 | 36/10/14 | ||

| Gnaphosa salsa Platnick & Shadab, 1975 | saGnGr | 3/0/1 | 8/1/5 | 3/0/2 | 1/1/1 | 15/2/9 | |||

| Gnaphosa synthetica Chamberlin, 1924 | SyGn-Gr | 3/0/0 | 0/1/0 | 3/1/0 | |||||

| Gnaphosa sp. 1 | Gn1-Gr | 3/1/5 | 1/1/0 | 10/1/21 | 1/0/5 | 1/0/7 | 16/3/38 | ||

| Gnaphosa sp.2 | Gn2-Gr | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Haplodrassus sp. 1 | Hap1Gr | 0/0/1 | 2/2/5 | 2/2/6 | |||||

| Haplodrassus sp. 2 | Hap2Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Haplodrassus dixiensis | HapdGr | 29/1/6 | 1/0/0 | 30/1/6 | |||||

| Chamberlin & Woodbury, 1929* Haplodrassus signifer | HapsigGr | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Koch, 1839 Herpyllus sp. | HerGr | 2/0/0 | 2/0/0 | ||||||

| Micaria sp. | MicGr | 0/1/4 | 1/0/1 | 1/1/9 | 2/2/14 | ||||

| Nodocion electricus | Nd-e-Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Chamberlin, 1924 Orodrassus sp. | O-Gr | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Scopoides cambridgeiGertsch & Davis, 1940 | ScaGr | 2/0/0 | 2/1/0 | 4/1/0 | |||||

| Scopoides nesiotes Chamberlin, 1924 | SneGr | 0/1/0 | 0/1/0 | ||||||

| Scopoides ochraceus Pickard-Cambridge, 1899 | SochGr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Scopoides sp. | ScoGr | 0/0/1 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/1 | |||||

| Sergiolus sp.** | SerGr | 1/0/1 | 0/0/1 | 1/0/2 | |||||

| Sosticus sp. | SosGr | 1/0/0 | 0/0/1 | 1/0/1 | |||||

| Talanites sp. | Tln-Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Trachyzelotes lyonneti Audouin, 1826* | Tr-l-Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Trachyzelotes sp. | TrGr | 3/1/5 | 4/2/1 | 7/3/6 | |||||

| Urozelotes sp. | UroGr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Zelotes anglo | Z-a-Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/1/0 | 2/1/0 | |||||

| Gertch & Riechert, 1976 Zelotes lasalanus Chamberlin, 1928 | Z-l-Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Zelotes sp. | ZGr | 1/0/1 | 1/0/1 | 9/0/4 | 11/0/6 | ||||

| Gnaphosidae sp. 1 | Gn1Gr | 0/0/1 | 0/0/3 | 0/0/4 | |||||

| Gnaphosidae sp. 2 | Gn2Gr | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Gnaphosidae sp. 3 | Gn3Gr | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Gnaphosidae sp. 4 | Gn4Gr | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Leptonetidae | Space web weavers | Leptonetidae sp. 1 | LeptSc | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | 2/0/0 | |||

| Linyphiidae | Sheet web weavers | Tapinopa sp. | TpaSh | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||

| Linyphiidae sp. 1 | LnySh | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Liocranidae | Ground. hunters | Neoanagraphis sp. | Ng-Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||

| Lycosidae | Ground hunters | Allocosa mokiensis | A-mk-Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||

| Gertsch, 1934 Arctosa sp. | ArctGr | 0/1/2 | 0/1/2 | ||||||

| Camptocosa parallela Banks, 1898 | C-p-Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Camptocosa sp. | C-Gr | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Pardosa sp. | PardGr | 0/1/25 | 0/0/19 | 0/1/44 | |||||

| Pirata sp. | PiraGr | 0/1/11 | 0/1/1 | 0/0/5 | 0/2/17 | ||||

| Rabidosa carrana | Rb-crrGr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Bryant, 1934 Rabidosa santrita | Rb-s-Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Chamberlin & Ivie, 1942 Rabidosa rabida | Rb-r-Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Walckenaer, 1837 Rabidosa sp. | Rb-Gr | 1/0/3 | 1/0/3 | ||||||

| Schizocosa sp. | SchGr | 0/1/0 | 0/1/0 | ||||||

| Trochosa sp. | Trsa-Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Varacosa hoffmannae Jimenez & Dondale, 1988 | VarhGr | 1/3/2 | 1/3/2 | ||||||

| Varacosa sp. | VarGr | 0/0/1 | 2/0/1 | 0/0/1 | 2/0/3 | ||||

| Lycosidae sp. 1 | Lyc1Gr | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | 0/0/4 | 0/0/6 | ||||

| Lycosidae sp. 2 | Lyc2Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Lycosidae sp. 3 | Lyc3Gr | 1/0/0 | 0/0/1 | 1/0/1 | |||||

| Lycosidae sp. 4 | Lyc4Gr | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | 0/0/2 | |||||

| Lycosidae sp. 5 | Lyc5Gr | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | 0/0/2 | |||||

| Lycosidae sp. 6 | Lyc6Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Lycosidae sp. 7 | Lyc7Gr | 1/0/0 | 1/0//0 | ||||||

| Lycosidae sp. 9 | Lyc9Gr | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Miturgidae | Other hunters | Miturgidae sp. 1 | Mitu-Oh | 0/0/1 | 1/0/0 | 1/0/1 | |||

| Nesticidae | Space web weavers | Nesticus sp. | Nst-Sc | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||

| Oecobiidae | Sensing web weavers | Oecobius sp.** | Oeco-ss | 1/0/1 | 1/0/1 | ||||

| Oonopidae | Groundhunters | Oonopidae sp. 1 | OonGr | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||

| Oxyopidae | Other hunters | Oxyopes sp. | Oxy-Oh | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||

| Philodromidae | Other hunters | Apollophanes margareta | Apolm-Oh | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||

| Lowrie & Gertsch, 1955 Apollophanes texanus | Apolt-Oh | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Banks, 1904* Apollophanes sp. | Apol-Oh | 0/1/0 | 0/0/1 | 2/0/1 | 0/0/1 | 2/1/3 | |||

| Ebo sp. | EboOh | 0/1/2 | 0/0/1 | 0/3/2 | 0/0/2 | 0/0/1 | 0/4/8 | ||

| Thanatus bungei Kulczynski, 1908 | ThbunOh | 0/1/0 | 0/1/0 | ||||||

| Tibellus duttoni | TibdutOh | 0/1/0 | 0/1/0 | ||||||

| Hentz, 1847 Tibellus sp. | TibOh | 0/1/3 | 2/0/7 | 0/0/1 | 2/1/11 | ||||

| Philodromidae sp. 1 | PhOh | 1/0/2 | 1/0/2 | ||||||

| Pisauridae | Sheet web weavers | Pisauridae sp. 1 | PrdSh | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||

| Salticidae | Other hunters | Anasaitis sp. | AnaOh | 0/0/5 | 2/0/0 | 2/0/5 | |||

| Attidops sp. | Att-Oh | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Bellota sp. | Bll-Oh | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Habronattus californicus | Habcal-Oh | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Banks, 1904 Habronattus conjuctus | Habcon-Oh | 0/0/1 | 0/1/0 | 0/1/1 | |||||

| Banks, 1898 | |||||||||

| Habronattus oregonensis | Habore-Oh | 2/0/0 | 0/0/2 | 1/0/0 | 3/0/2 | ||||

| Peckham & Peckham, 1888 Habronattus sp. 1 | Hab1-Oh | 7/0/4 | 1/2//4 | 3/0/6 | 0/0/1 | 11/2/15 | |||

| Habronattus sp. 2 | Hab2-Oh | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Hasarius sp. | Hass-Oh | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Paradamoetas sp. | Pmt-Oh | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Pellenes sp. | Pell-Oh | 1/0/1 | 1/0/0 | 0/1/0 | 0/0/1 | 2/1/2 | |||

| Phidippus sp. | PhidOh | 0/1/1 | 0/1/1 | ||||||

| Plexippus sp. | Plx-Oh | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Salticus sp. | SaltsOh | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | 0/0/2 | |||||

| Sitticus sp. | Sitt-Oh | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Salticidae sp. 1 | Sal1Oh | 0/0/1 | 1/0/7 | 0/0/2 | 1/0/10 | ||||

| Salticidaesp. 2 | Sal2Oh | 1/0/2 | 0/0/1 | 1/0/3 | |||||

| Salticidae sp. 3 | Sal3Oh | 1/0/0 | 1/1/0 | 2/1/0 | |||||

| Salticidae sp. 4 | Sal4Oh | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Salticidae sp. 5 | Sal5Oh | 0/0/1 | 0/0/2 | 0/0/3 | |||||

| Scytodidae | Other hunters | Scytodes sp. | Syt-Oh | 2/0/0 | 1/0/0 | 3/0/0 | |||

| Scytodidae sp. 1 | Scy1Oh | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Sicariidae | Ambush hunters | Loxosceles deserta | Lx-d-Ab | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||

| Gertsch, 1973 Loxosceles sp. | Lx-Ab | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Theridiidae | Space web weavers | Asagena medialis | AsamdSc | 4/0/0 | 1/0/0 | 5/0/0 | |||

| Banks, 1898 Asagena sp. | AsaSc | 0/0/1 | 1/0/0 | 1/0/1 | |||||

| Theridon sp. | Thdn-Sc | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Theridiidae sp. 1 | ThSc | 2/0/1 | 2/0/1 | ||||||

| Thomisidae | Ambush hunters | Mecaphesa sp. | MecaAb | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||

| Misumena sp. | MisnAb | 1/0/1 | 0/0/1 | 1/0/2 | |||||

| Misumenoides sp. | MmedAb | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Misumenops sp. | MisopAb | 0/2/0 | 0/2/0 | ||||||

| Xysticus bolivari | XblvAb | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Gertsch, 1953 Xysticus lassanus | XlassAb | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | ||||||

| Chamberlin, 1925 Xysticus sp. | XAb | 2/2/3 | 1/1/0 | 0/0/1 | 3/3/4 | ||||

| Thomisidae sp. 1 | Th1Ab | 2/0/2 | 2/0/2 | ||||||

| Thomisidae sp. 2 | Th2Ab | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 | ||||||

| Zorocratidae | Ground hunters | Zorocrates karli | ZorKGr | 2/0/0 | 2/0/0 | ||||

| Gertsch & Riechert, 1976 Zorocratidae sp. 1 | ZorGr | 0/1/0 | 0/1/0 | ||||||

| Total abundance | 186 | 56 | 381 | 54 | 24 | 701 | |||

| Richness | 76 | 34 | 87 | 22 | 8 | 144 |