We captured Promops centralis and recorded its echolocation calls in Bahía de Kino, Sonora, which represents the first record of this species for the state of Sonora, Mexico. Our new record extends the distribution of P. centralis at least 1,300km northwest from the northernmost known locality, Cuautla, Jalisco. Until now, there was no evidence of the occurrence of P. centralis in the deserts of northern Mexico. These new records are ecologically significant as they show that this species also occurs in extreme dry areas such as the Sonoran Desert. Our findings suggest that P. centralis may be more widely distributed than previously thought.

Se capturó al murciélago Promops centralis y se grabaron sus llamadas de ecolocalización en la localidad de Bahía de Kino, Sonora; este es el primer registro de la especie para el estado de Sonora, México. Este nuevo registro amplía la distribución de P. centralis por lo menos 1,300km al noroeste de la localidad más norteña previamente conocida, Cuautla, Jalisco. Hasta ahora no existía evidencia de la presencia de P. centralis en los desiertos del norte de México. Este nuevo registro es de importancia ecológica ya que por primera vez se muestra que esta especie puede subsistir en áreas extremadamente secas como el Desierto de Sonora. Nuestro hallazgo sugiere que P. centralis puede estar más ampliamente distribuido de lo que se pensaba con anterioridad.

The Molossidae is a diverse group of bats (fourth largest bat family, ca. 100 species), with most of the species occurring in tropical and subtropical regions (Simmons, 2005). Molossids are typical open space bats that hunt high up in the air and roam over large distances. They are rarely captured in mist nets so there is a general lack of information on many species. The genus Promops is restricted to the New World and currently encompasses 3 species (Gregorin & Chiquito, 2010): Promops centralis, Promops nasutus and Promops davisoni. P. centralis is the most widely distributed, from Mexico (Jalisco to Yucatán) throughout South America, from Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, to the Amazon basin in Brazil, western Bolivia, Paraguay, northeastern Argentina and the northern coast of Brazil, Guianas, and Venezuela (Eger, 2008; Pacheco, Cadenillas, Salas, Tello, & Zeballos, 2009; Simmons, 2005). Despite its large distributional range, little is known about the ecology of this species. Like most molossids, P. centralis possesses long and narrow-tipped wings (high wing loading and aspect ratio) which are well suited to fly at high speed but are less suited for high maneuverability (Freeman, 1981; Norberg & Rayner, 1987). In accordance, these bats are known to forage in open areas above the forest canopy or in open landscapes (Jung, Molinari, & Kalko, 2014; Kalko, Estrada-Villegas, Schmidt, Wegmann, & Meyer, 2008). P. centralis occurs in a very diverse range of habitats such as rain forest, tropical dry forest and pine-oak (Arita, 1997; Sánchez-Cordero, Bonilla, & Cisneros, 1993; Simmons & Voss, 1998), pastures (MacSwiney, Bolivar, Clarke, & Racey, 2006), and has even been reported in urban areas (Jung & Kalko, 2011; Regueras & Magaña-Cota, 2008). The echolocation calls of P. centralis are very conspicuous as they are characterized by upward frequency modulation similar to the genus Molossops (Jung et al., 2014). Within sequences up- and downward modulated calls can alternate irregularly. Species-specific variation of echolocation calls has been previously described in detail (while assigning it to Cynomops mexicanus by MacSwiney et al., 2006).

In Mexico, this species has been recorded from Jalisco southward throughout the west coast to the Yucatán Peninsula. We report here the capture of this species for the first time in the extreme north of Mexico, in the state of Sonora, where there was no record of this species in the northern desert habitats of Mexico.

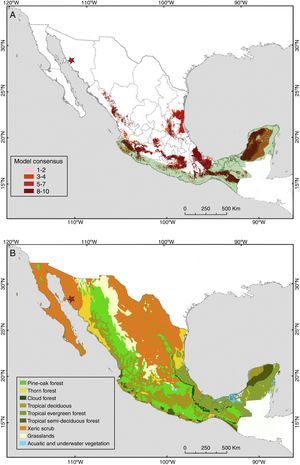

Field work was conducted on the nights of the 8th and 9th of April 2014 in Bahía de Kino, Sonora. Our study site was one of the few artificial water reservoirs in this area (28°50′1.09″N, 111°35′57.20″W). The pond had a size of ca. 90m×90m with some palm trees close to the edge of the water and mainly surrounded by crops (Fig. 1). However, the pond is relatively close to the natural vegetation typical for the Sonoran Desert, dominated by small shrubs and columnar cacti (Mexican giant cardon: Pachycereus pringlei, saguaro: Carnegiea gigantea, organ pipe cactus: Stenocereus thurberi) (Van Devender, 2002). We used mist nets for capturing bats and acoustic monitoring to record the echolocation calls of all the bats flying near the study site. Captured bats were identified using a bat identification guide (Medellín, Arita, & Sánchez-Herrera, 2008). Acoustic recordings were obtained using a real time acoustic ultrasound recording device (batcorder, ecoObs GmbH, Nürnberg, Germany) located at 1.5m above the ground. Both, mist netting and use of the acoustic recording device started at sunset and ended at midnight. We followed the guidelines for the use of wild mammal species in research as recommended by the American Society of Mammalogists (Sikes & The Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists, 2016). All captures were carried out under permission of the Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Mexico (FAUT-0001).

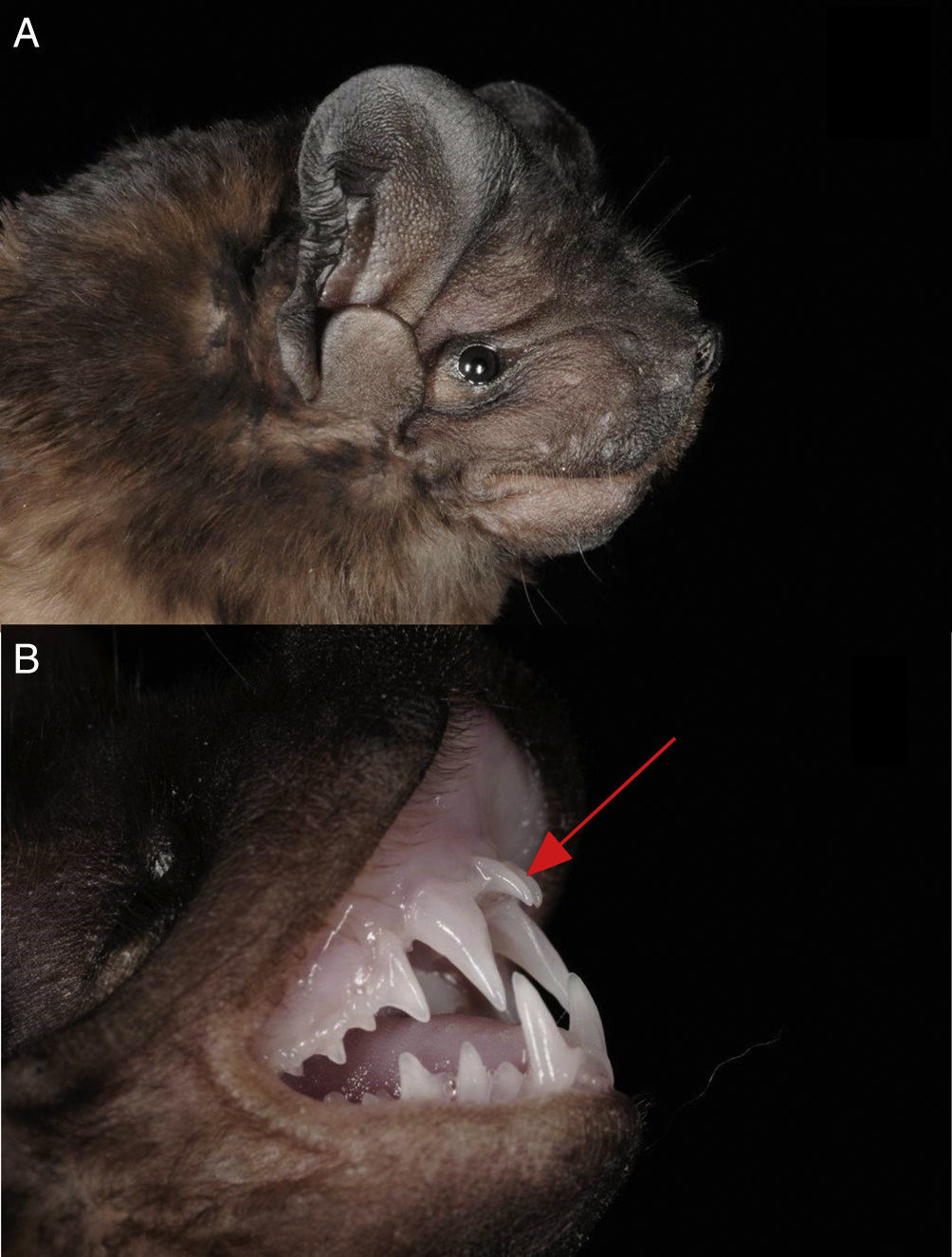

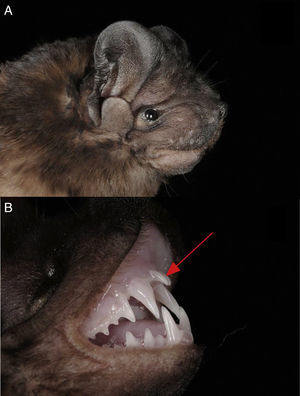

In total we captured 12 individuals of 2 bat families (Vespertilionidae and Molossidae). We identified 2 individuals of P. centralis, 1 in each capture night, both individuals presented the characteristic morphological features of P. centralis: upper lip without grooves (Fig. 2A), forearm less than 56mm, dark pelage (darker in the dorsal part than in the ventral part) and the incisors protruding substantially from the front of the canines (Fig. 2B). The first captured individual was an adult male, reproductively inactive, with a forearm of 54.8mm, the time of capture was around 22:00h. The collected individual was deposited in the National Collection of Mammals, UNAM, Mexico (catalog number 47626). The second individual, captured around 20:00h and released after taking measurements and photographs, was an adult male, reproductively inactive with a forearm of 55.4mm.

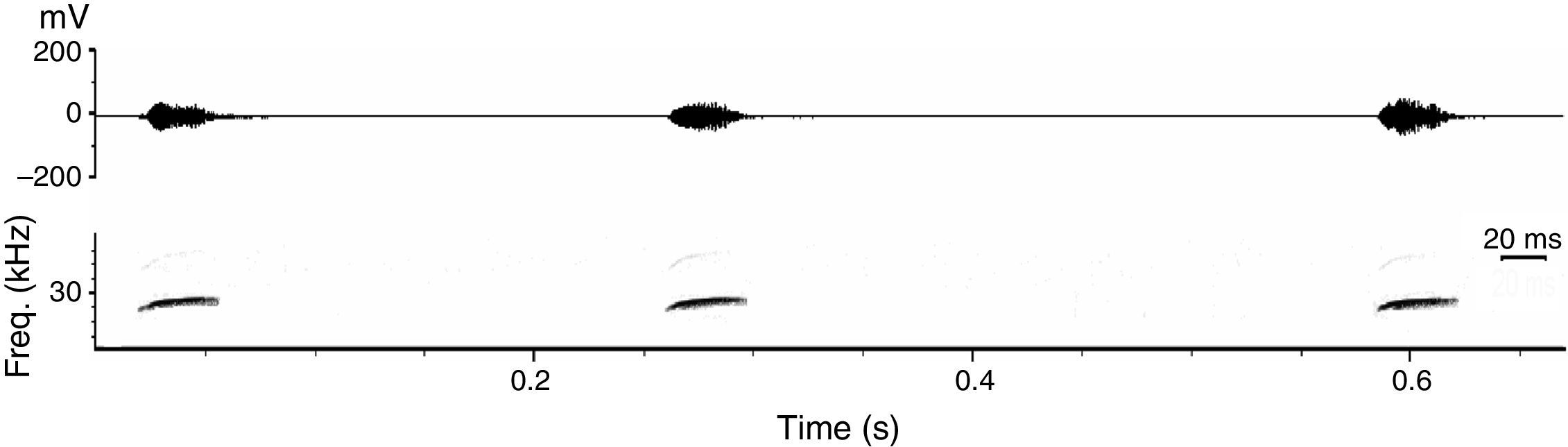

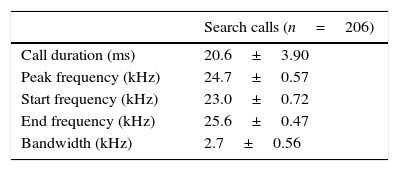

We analyzed 13 echolocation sequences (n=206 upward modulated echolocation calls) of P. centralis. Corroborating with previous publications, this species has very particular echolocation calls (Jung et al., 2014), which are easily identified using acoustic recordings for species inventory. Contrary to most molossids, their search calls are upward modulated quasi-constant frequency calls with a variable upward modulated FM-component at the beginning (i.e., the start frequency is lower than the end frequency). Call sequences are characterized by interspersed downward-modulated signals, especially before prey-capture attempts. Upward and downward modulated signals do not overlap in frequency range. The upward modulated search calls of P. centralis are long, low frequency quasi-constant calls with the highest energy in the first harmonic (Fig. 3; Table 1).

Call parameters of the upward modulated calls (mean±SD) of Promops centralis. We analyzed a total of 206 calls from 13 different sequences.

| Search calls (n=206) | |

|---|---|

| Call duration (ms) | 20.6±3.90 |

| Peak frequency (kHz) | 24.7±0.57 |

| Start frequency (kHz) | 23.0±0.72 |

| End frequency (kHz) | 25.6±0.47 |

| Bandwidth (kHz) | 2.7±0.56 |

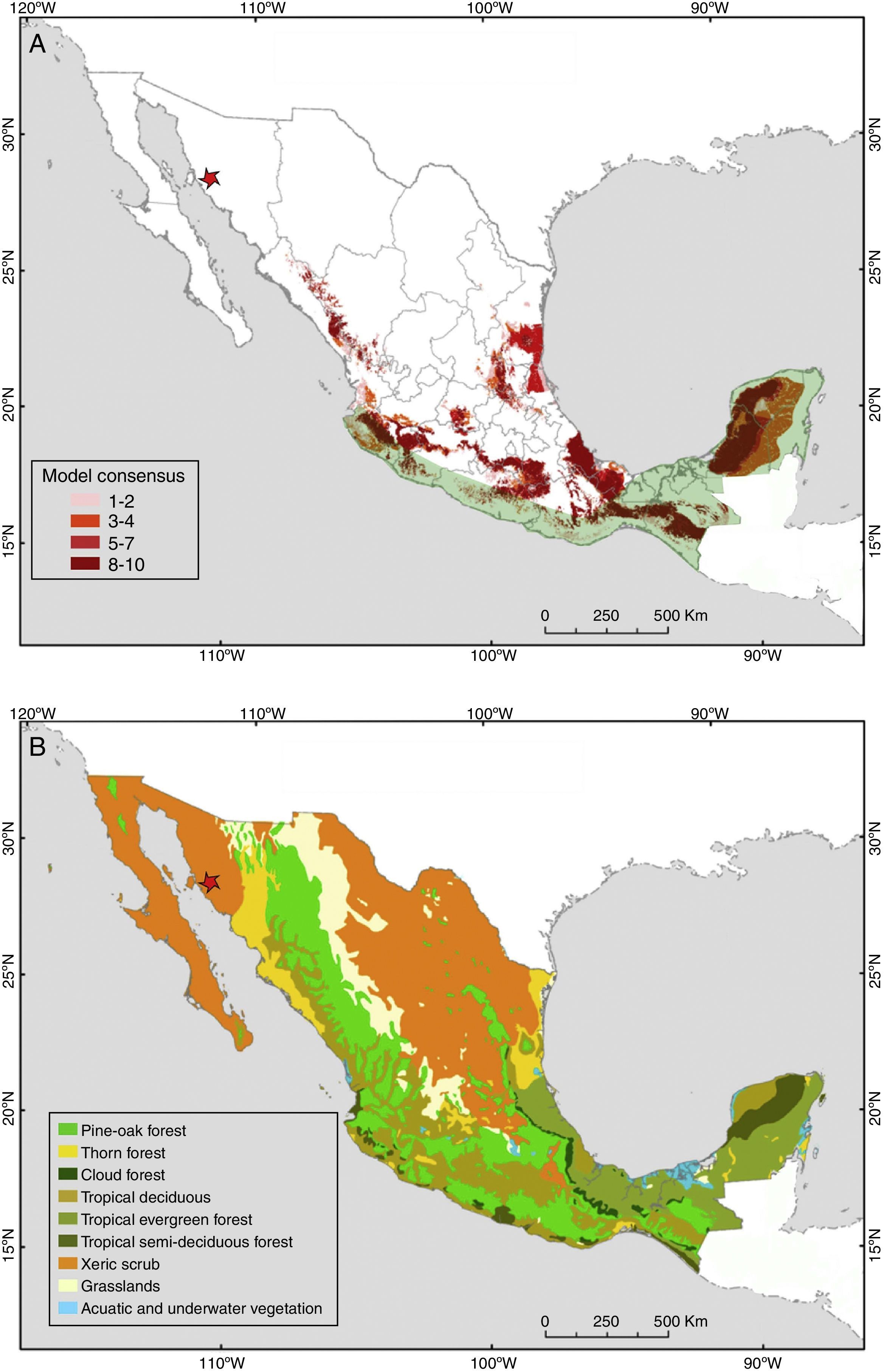

Our new records of P. centralis, besides being the first for the state of Sonora, extend the distributional range of this species by 1300km northwesterly. So far, the northernmost records of P. centralis were from Cuautla, Jalisco (Watkins, Jones, & Genoways, 1972) and one recent record from the city of Guanajuato (Regueras & Magaña-Cota, 2008). Additionally, this is the first record of P. centralis for the Sonoran Desert (xeric shrublands). This type of habitat covers large part of northwestern Mexico and southwest of the United States, with an approximate area of 260,000km2 (Phillips & Comus, 2000). The xeric shrublands of the northern Mexican deserts covered originally approximately 40% of the Mexican territory (Rzedowski, 1978; Fig. 4B), nowadays they cover only ca. 30% of the country (Inegi, 2005). Our finding of the occurrence of P. centralis in this type of habitat suggests that the potential distribution of this species (Fig. 4A) may cover a much larger area than previously thought.

(A) Potential distribution of Promops centralis in Mexico (modified from Ceballos, Blanco, González y Martínez, 2006). Light green shading indicates the current known distribution of this species in Mexico (modified from Medellín et al., 2008). The red star represents the location of the new records reported in this study. (B) Potential vegetation of Mexico (modified from Rzedowski, 1990). These captures were in a type of habitat (xeric shrublands) where P. centralis was considered to be absent. This habitat type is extensively distributed in the north of Mexico, therefore, this species may be more widely distributed than previously thought.

In addition to the 2 captures, we also recorded many echolocation passes of P. centralis during the 2 nights of acoustic monitoring. The measurements of the call parameters in this study are similar to those previously reported for P. centralis (Jung et al., 2014; MacSwiney et al., 2006). In contrast to most molossids, which demonstrate a high variability in echolocation call frequencies, hampering acoustic species identification (Gillam et al., 2009; Kalko et al., 2008) echolocation calls of P. centralis, are very characteristic and thus a reliable indicator for the occurrence of this species. Thus acoustic monitoring can be an important tool to enhance our knowledge about the ecology of this species.

In dry habitats, where water is limited, the few available water bodies are hot spots of activity of the regional fauna. We recorded echolocation calls and captured P. centralis while the animals were approaching the pond for drinking or capturing insects gathered near the water. With extensive monitoring efforts, combining acoustic and mist netting techniques at similar locations it may be possible to record this species at additional localities in the northern deserts of Mexico where this species has not yet been found. Our results indicate that, more than ever before, standardized, careful acoustic surveillance is rapidly becoming an essential tool for biodiversity monitoring.

We want to thank all the people who contributed to the field work. Scientific collecting permits were provided to R.A.M. by the Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (FAUT-0001). This study was supported by a joint DFG-Conacyt Bilateral Cooperation program under the number 190901 [to R.A.M] and TS 81/8-1 and 8-2 [to M.T. and K.J.]

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.