Observations on the diet of Crotalus triseriatus (Mexican dusky rattlesnake) from central México are reported. We recovered the remains of 12 individual prey items from 11 different snakes. Prey included 7 rodents, 4 lizards and 1 salamander. These observations reinforce that C. triseriatus consumes a diverse diet and utilizes varied foraging strategies.

Se registran observaciones sobre la dieta de Crotalus triseriatus (serpiente de cascabel oscura mexicana) en el centro de México. Recuperamos 12 diferentes presas provenientes de 11 serpientes. Las presas incluyen 7 roedores, 4 lagartijas y 1 salamandra. Nuestras observaciones sugieren que C. triseriatus tiene una dieta diversa y presenta hábitos alimenticios variados.

Basic information describing the natural history and ecology of most Mexican snakes remains fragmentary, particularly for species endemic to the country. Published descriptions of the diets of many Mexican rattlesnakes are limited by small datasets, and often are based on little more than conjecture and anecdote (e. g., Campbell and Lamar, 2004; Mociño-Deloya et al., 2008; Meik et al., 2012). In the absence of more exhaustive studies, combining information from various published anecdotal accounts can provide a more complete view than can each individual observation or small dataset. Here, we provide data concerning the diet of C. triseriatus, a small rattlesnake (68.3cm total length maximum size recorded; Klauber, 1997) endemic to México and distributed in the highlands of the Transverse Volcanic Cordillera, from west-central Veracruz westward through parts of Puebla, Tlaxcala, State of México, Morelos, and extreme northern Guerrero to western Michoacán and Jalisco (Flores-Villela and Hernández-García, 1989, 2006; Campbell and Lamar, 2004). We also summarize previously published observations concerning the diet of this species.

We collected 6 adult and 1 neonate C. triseriatus during August-September 2007 and October 2008 in the state of México in the municipalities of Jocotitlán, (19°43' N, 99°46' W, 2 800–3 000m asl), and Chapa de Mota (19°46' N, 99°35' W, 2 675m asl). We encountered most C. triseriatus along the margins of crop fields and pastures, often along the interface between areas modified by agricultural use and more natural vegetation. We also examined 2 adult and 2 neonate C. triseriatus from the Museo de Zoología de la Facultad de Ciencias (MZFC) which contained prey material.

We obtained the remains of 7 prey items from snakes captured in the field. Most snakes were found in the morning or early afternoon, and were processed the same day they were found. All snakes were anesthetized with isoflurane (Setser, 2007), then sexed, measured and weighed. Two snakes spontaneously regurgitated prey items. Prey remains were obtained from the remaining snakes by expressing feces during processing, and by collecting naturally voided feces from snakes while held captive. We preserved fecal samples and regurgitated prey in 96% ethanol for subsequent identification. We obtained 5 individual prey items from 4 preserved specimens; 1 neonate snake contained the remains of 2 different prey items. We identified lizard remains to the greatest resolution possible using morphological or scale characters. We identified mammalian remains based on microscopic examination of hair (Moore et al., 1974), and by examination of tooth and bone characters (Whorley, 2000).

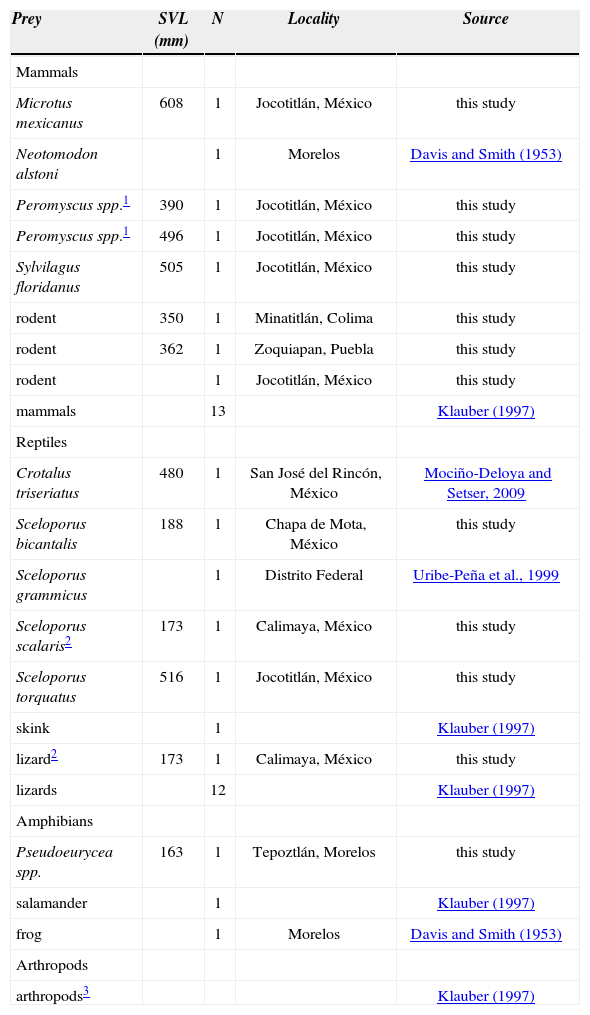

In total, we obtained prey remains from 11 snakes (4 females and 7 males). Snakes included 3 neonates and 8 adult or subadult snakes. We found mammal hair and/or bones in 7 samples; 4 of these samples were identified to genus or species, the 3 remaining samples could only be identified as rodents. Two of 3 neonate snakes had eaten lizards. The other neonate had consumed a salamander. In contrast, all mammals were taken by larger snakes (350–608mm SVL; Table 1).

Prey items of Mexican dusky rattlesnakes (Crotalus triseriatus) from this study and the literature. Snake snout-vent length (SVL, in mm), sample number (N) and locality are given when available

| Prey | SVL (mm) | N | Locality | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammals | ||||

| Microtus mexicanus | 608 | 1 | Jocotitlán, México | this study |

| Neotomodon alstoni | 1 | Morelos | Davis and Smith (1953) | |

| Peromyscus spp.1 | 390 | 1 | Jocotitlán, México | this study |

| Peromyscus spp.1 | 496 | 1 | Jocotitlán, México | this study |

| Sylvilagus floridanus | 505 | 1 | Jocotitlán, México | this study |

| rodent | 350 | 1 | Minatitlán, Colima | this study |

| rodent | 362 | 1 | Zoquiapan, Puebla | this study |

| rodent | 1 | Jocotitlán, México | this study | |

| mammals | 13 | Klauber (1997) | ||

| Reptiles | ||||

| Crotalus triseriatus | 480 | 1 | San José del Rincón, México | Mociño-Deloya and Setser, 2009 |

| Sceloporus bicantalis | 188 | 1 | Chapa de Mota, México | this study |

| Sceloporus grammicus | 1 | Distrito Federal | Uribe-Peña et al., 1999 | |

| Sceloporus scalaris2 | 173 | 1 | Calimaya, México | this study |

| Sceloporus torquatus | 516 | 1 | Jocotitlán, México | this study |

| skink | 1 | Klauber (1997) | ||

| lizard2 | 173 | 1 | Calimaya, México | this study |

| lizards | 12 | Klauber (1997) | ||

| Amphibians | ||||

| Pseudoeurycea spp. | 163 | 1 | Tepoztlán, Morelos | this study |

| salamander | 1 | Klauber (1997) | ||

| frog | 1 | Morelos | Davis and Smith (1953) | |

| Arthropods | ||||

| arthropods3 | Klauber (1997) |

In 2 cases we were able to obtain measurements of prey mass, a 28.7g Sceloporus torquatus eaten by an adult snake (20.4% of the snake's mass) and a 3.9g Sceloporus bicantalis consumed by a neonate snake (46.4 % of the snake's mass), other prey items were too digested to allow estimation of their original masses. One snake contained more than 1 prey item, a small (173mm SVL) neonate male which contained a freshly ingested Sceloporus scalaris, as well as a second lizard too digested to be identified.

Mammals represented the largest proportion of prey in our sample. Many rattlesnakes frequently eat ectothermic prey when young, but increasingly consume rodents at larger sizes (Holycross et al., 2002), a pattern also present in our data from C. triseriatus. While adult snakes relied more heavily on mammals, we also encountered an adult that had taken a lizard. Although Klauber (1997) did not list body length for the snakes he examined, he recorded equal numbers of lizards and mammals by the snakes in his sample, suggesting that C. triseriatus may continue to consume lizards as adults, as do many small rattlesnakes (Holycross et al., 2002).

An Eastern Cottontail, Sylvilagus floridanus, had been consumed by 1 snake. We were not able to determine the age of this prey item; however, because this is a relatively large prey, it is probable that the individual was a juvenile. In a study of a larger rattlesnake from the same region, Crotalus polystictus was observed to only consume juvenile S. floridanus (E. Mociño-Deloya, unpubl. data), and it is unlikely that the smaller C. triseriatus takes larger prey than C. polystictus.

Our data, along with previously available data, indicate that C. triseriatus is a generalist predator which consumes a highly diverse diet. Although prey records remain scant, this species is known to consume small rodents, pups of larger mammals, lizards, snakes, amphibians, insects and centipedes (Table 1). The latter 4 prey categories are uncommon prey for rattlesnakes (Campbell and Lamar, 2004) and highlight the diversity of prey taken by C. triseriatus. The consumption of a variety of arthropods, reported by Klauber (1997), is notable as vertebrate eating snakes seldom include insects in their diet (Campbell and Lamar, 2004). Furthermore, it may be inferred that this species likely forages both by day, when lizards are active, and at dusk or night, when many rodents are most active. Similarly, although we assume that like most rattlesnakes (Campbell and Lamar, 2004), C. triseriatus primarily encounters prey through ambush foraging, the consumption of an Eastern Cottontail pup and a snake presumed to have been ingested as carrion (Mociño-Deloya and Setser, 2009) indicates that it may opportunistically forage actively.

Museum specimens: MZFC 7595, 11382, 11383, 19744.

We thank Semarnat, and in particular F. Sánchez, for providing necessary permits (SGPA/DGVS/06843/07) to EMD. We also thank C. Setser, and D. Setser for providing logistical assistance. We thank Oscar Flores Villela for loan of MZFC specimens.