Patterns of diversity are scale dependent and beta-diversity is not the exception. Mexico is megadiverse due to its high beta diversity, but little is known if it is scale-dependent and/or taxonomic-dependent. We explored these questions based on the self-similarity hypothesis of beta-diversity across spatial scales. Using geographic distribution ranges of 2 513 species, we compared the beta-diversity patterns of 4 groups of terrestrial vertebrates, across 7 spatial scales (from ~10km2 to 160 000km2), within 5 different (historically and environmentally) regions in Mexico: Northwest, Northeast, Centre, Southeast and the Yucatán Peninsula. We found that beta-diversity: 1) was not selfsimilar along the range of scales, being larger than expected according to the null model at coarse scale, and lower, but not significantly different, to expected at intermediate and fine scales; 2) varied across spatial scales, depending on the taxonomic group and on the region; 3) was higher at coarser scales; 4) was highest in the Centre and Southeast regions, and lowest in the Yucatán Peninsula, and 5) was higher for amphibians and reptiles than mammals and birds. As a consequence, beta-diversity of each group contributes differentially to the megadiversity of Mexico, likely due to a variation in the biogeographical histories and the perception of each group to environmental heterogeneity. These results show the importance of identify the appropriate geographical scale for biodiversity conservation analyses, such as for example, the analysis of complementarity.

Los patrones de diversidad son dependientes de la escala y la diversidad beta no es la excepción. Se ha propuesto que México es megadiverso por su alta diversidad beta, aunque existe poca información sobre si dicha diversidad es dependiente de la escala espacial, regiones geográficas y/o diferentes grupos taxonómicos. Aquí abordamos estas preguntas de manera cuantitativa, con base en la hipótesis de auto-similitud en el escalamiento de la diversidad. Utilizando áreas de distribución de 2 513 especies de vertebrados terrestres mexicanos, comparamos los patrones de diversidad beta de los 4 grupos taxonómicos, a lo largo de 7 escalas espaciales (de ~10km2 a 160 000km2) y en 5 regiones con diferentes características históricas y ambientales (Noroeste, Noreste, Centro, Sur y la Península de Yucatán). Se observó que la diversidad beta: 1) no resultó auto-similar en el intervalo de escalas analizado, siendo, a escalas gruesas, mayor a lo esperado de acuerdo con el modelo nulo, y a escalas finas e intermedias menor aunque no significativamente diferente a lo esperado; 2) varió a diferentes escalas espaciales según el grupo taxonómico y región; 3) fue mayor a escalas geográficas gruesas; 4) fue mayor en las regiones del centro y sureste y menor en la península de Yucatán, y 5) fue mayor en anfibios y reptiles que en mamíferos y aves. En consecuencia, la diversidad beta de cada grupo taxonómico contribuye de manera distinta a la megadiversidad de México, probablemente debido a las diferencias en la historia biogeográfica y en la percepción de la heterogeneidad ambiental de cada grupo taxonómico. Los resultados muestran la importancia de la detección de la escala apropiada para optimizar análisis para la conservación de la biodiversidad, como es el caso del análisis de complementariedad.

Patterns of diversity and distribution of species are scale dependent (Whittaker et al., 2001; Willis and Whittaker, 2002; Rahbek, 2005), implying that form and properties of those patterns will change correspondingly to spatial scale. Beta diversity, the component of diversity that quantifies changes in species composition, is correlated with environmental heterogeneity, which is ultimately related to spatial scale. As geographical area increases, it is likely that additional habitat types and/or different geographic features are included (Rosenzweig, 1995), thus, beta diversity should be scale-dependent (Koleff et al., 2003; Tuomisto, 2010; Barton et al., 2013).

In addition to its sensitiveness to spatial scale, beta diversity is per se a scaling factor that relates 2 or more ‘inventories’ of species (Shmida and Wilson, 1985). Beta diversity detects the contribution of the diversity at finer spatial scales (alpha diversity) to coarse scales (gamma diversity). For example, in a region of high gamma diversity where alpha diversity is significantly low, beta diversity should be necessarily high in order to ‘compensate’ the low alpha diversity. Conversely, if alpha diversity is high, beta diversity has to be low.

Investigating patterns and processes explaining beta diversity across spatial scales is crucial for understanding structure and maintenance of biodiversity (Harte et al., 2005). Moreover, detailed information on how beta diversity is correlated with spatial scale improves the estimation of extinction rates due to habitat loss (e. g., Tanentzap et al., 2012), land protection policies for designing efficient and accurate monitoring strategies, and the understanding of the structural mechanisms of ecological diversity (Harte et al., 2005; Drakare et al., 2006; Barton et al., 2013).

There are different approaches to study beta diversity as a scaling factor of diversity. One of the most common approaches is centered in the use of the additive model relating alpha and gamma diversity (Loreau, 2000; Crist and Veech, 2006; Jost, 2007; Jost et al., 2010); that is y= β + αmean, where γ is gamma diversity, the total number of species of the region and a mean is alpha diversity, the average species number of the sites that conform the region. This approach allows the use of the same units (number of species) for alpha, beta and gamma diversity. However, results depend on the species richness of the system, thus comparisons among different systems are not straightforward. This disadvantage can be overcome by using the multiplicative formula, defined as the ratio between the gamma diversity to the mean of alpha diversity, βW= γαmean-1 (Whittaker, 1960, 1972). Another alternative is to use the species-area relationship S= cAz (SAR, Crawley and Harral, 2001; Lennon et al., 2002; Šizling and Storch, 2004), where S is the number of species, c is the intercept, A is the area of the sampled units, and z is the slope, that is, the rate at which new species accumulates as area increases. In its power function form (plotting the log values of species number and the log values of the area), the SAR produces straight lines. The slope z of the lines is related to beta diversity: a steeper slope corresponds to a faster accumulation of species, indicating higher beta diversity (Rosenzweig, 1995). This approach also allows a direct comparison between systems of different richness (Crawley and Harral, 2001). Arita and Rodríguez (2002) proposed a method that integrates the equations that relate alpha and gamma diversity in a multiplicative way, and the SAR. This method has the additional advantage of providing an explicit null hypothesis of self-similarity, that is, ‘if the species area relationship is a power function, then beta diversity most be scale invariant’ (Arita and Rodríguez, 2002; Harte et al., 1999).

Up to date no clear patterns regarding the self-similarity of beta diversity have emerged. Whereas some studies report that beta diversity is self-similar (e. g., Noguez et al., 2005), other studies found that beta diversity differs from self-similarity, at least in some ranges of the scales (Crawley and Harral, 2001; Arita and Rodríguez, 2002; Ulrich and Buszko, 2003; McGlinn et al., 2012;Jones et al., 2011). Clearly, more studies are needed for elucidating the spatial scaling of beta diversity and its conservation implications (Evans et al., 2005).

Mexico is one of the megadiverse countries in the world; however, unlike other megadiverse countries, its high biological diversity does not depend on high values of alpha diversity, but rather is explained by exceptionally high beta diversity (Arita and Rodríguez, 2002). Indeed, the empirical evidence for Mexican vertebrates shows consistent high beta diversity regardless of the spatial scale. Studies ranging from landscape scale (~1 to 10km2) (Moreno and Halffter, 2001) to coarse scales (~2 500 to 160 000km2), report high beta diversity for mammals (Arita and Rodríguez, 2002; Rodríguez and Arita, 2004; Koleff et al., 2008). Similar studies at coarse spatial scale for reptiles and amphibians (~2 500km2) (Flores-Villela et al., 2005; Koleff et al., 2008) and birds (Lira-Noriega et al., 2007; Koleff et al., 2008), have also found high beta diversity.

Nonetheless, on one side, the variety of methods applied to measure beta diversity, and the high variation in the scale of analyses in both elements of scale, extent and grain (sensuBarton et al., 2013), difficult comparisons between studies. Thus, there is a need to systematically explore the scaling patterns of beta diversity, in order to elucidate whether the hypothesis that Mexico is particularly high beta diverse is sustained at different spatial scales.

On the other side, it is well documented that the capacity of dispersion of the species is related to beta diversity (Baselga et al., 2012). Some studies have demonstrated the relatively low beta diversity of birds, the group of the highest dispersion capacity among vertebrates (Buckley and Jetz, 2008). Conversely, for amphibians and reptiles, in the groups with lower dispersal capacity, the studies report the highest beta diversity (e. g., Qian, 2009; Dobrovolski et al., 2012). This tendency was clearly documented for the vertebrates of Mexico at the country level (scale of 2 500km2): amphibians and reptiles have the highest beta diversity, followed by mammals, while birds have the lowest beta diversity (Koleff et al., 2008). Recently, Calderón-Patrón et al. (2013) found that in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, southern Mexico, at fine and intermediate scales (cells of 10 x 10km and 20 x 20km respectively), birds have higher dissimilarities that amphibians, contrarily to the idea that vagility and beta diversity are negatively related. These new findings reinforce the necessity to investigate the effect of the scale in the beta diversity patterns of different taxonomic groups, and to find out whether the tendency found at the scale of 2 500km2 (Koleff et al., 2008) is sustained at other spatial scales.

Herein, we explore systematically and quantitatively the scaling patterns of beta diversity for Mexican terrestrial vertebrates. Specifically, 1) we test the hypothesis of selfsimilarity in beta diversity; 2) identify the spatial scale or scales where beta diversity is higher or lower than the expected self-similar value; 3) explore whether the pattern is maintained in different geographic regions, and 4) identify general patterns of beta diversity between taxonomic groups.

Materials and methodsDatabasesWe used 3 comprehensive databases of distribution maps based on Environmental Niche Models (ENM) of 2 513 terrestrial vertebrates distributed in Mexico. Data were compiled from different sources, including: 883 resident land birds (Navarro-Sigüenza et al., 2003; Navarro-Sigüenza and Peterson, 2007), 344 mammals (Ceballos et al., 2002), 364 amphibians, and 811 reptiles (Ochoa-Ochoa et al., 2006). The distribution models ranged between 70 and 97% of the total species of each group of terrestrial vertebrates occurring in Mexico. These models have been considered robust and an adequate approximation to the Mexican distribution range for terrestrial vertebrates, and have been used for biogeography and conservation studies (e. g., Sánchez-Cordero et al., 2005; Lira-Noriega et al., 2007; Pronatura-Mexico and The Nature Conservancy, 2007; Conabio-Conanp-TNC-Pronatura-FCF, UANL, 2007; Munguía et al., 2008; Koleff et al., 2008; Ochoa-Ochoa et al., 2014;Villalobos et al., 2013).

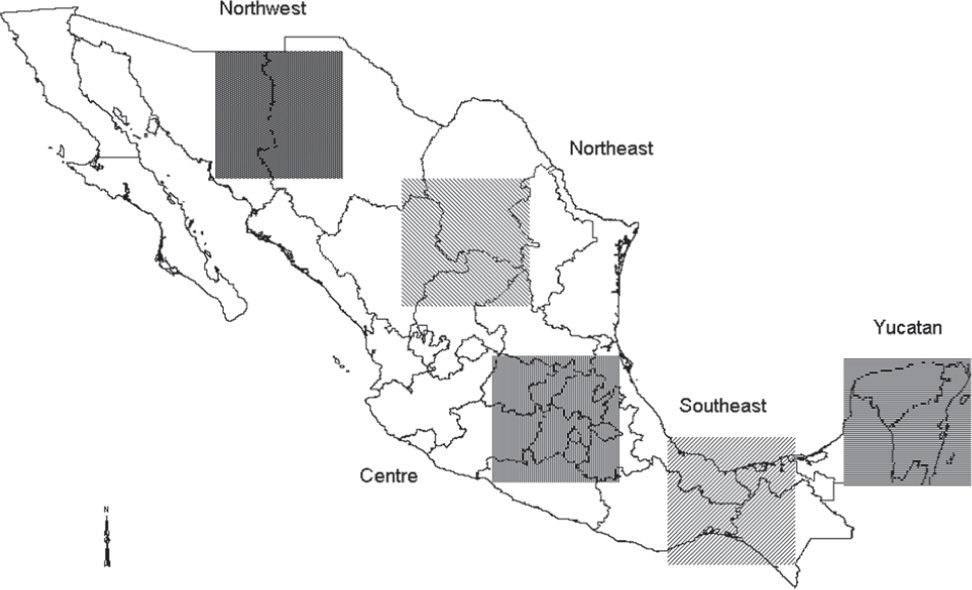

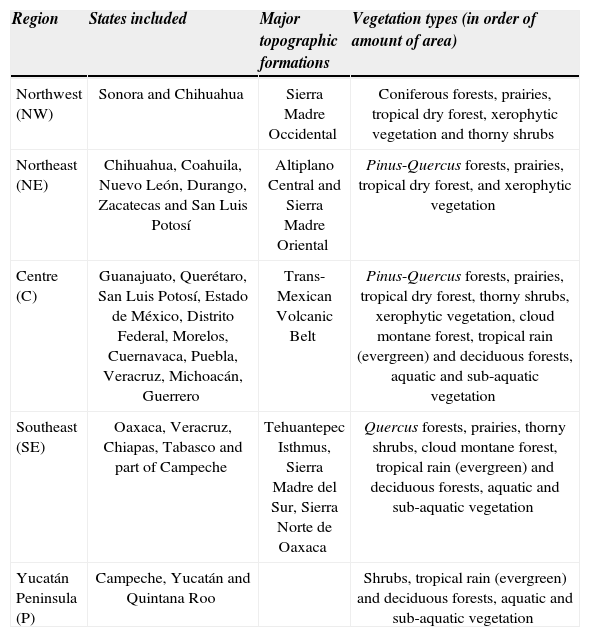

RegionsWe selected 5 regions representing contrasting environmental conditions in Mexico: Northwest (NW), Northeast (NE), Centre (C), Southeast (SE) and the Yucatán Peninsula (P) (Fig. 1). Two of those regions were placed within the Nearctic realm, 2 were located in the Neotropic realm, and 1 was positioned in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt. The extent of each region was 160 000km2 (400 x 400km side). A brief description of the each region can be found in Table 1.

Brief description of each region selected for the analyses of scaling beta diversity

| Region | States included | Major topographic formations | Vegetation types (in order of amount of area) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northwest (NW) | Sonora and Chihuahua | Sierra Madre Occidental | Coniferous forests, prairies, tropical dry forest, xerophytic vegetation and thorny shrubs |

| Northeast (NE) | Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, Durango, Zacatecas and San Luis Potosí | Altiplano Central and Sierra Madre Oriental | Pinus-Quercus forests, prairies, tropical dry forest, and xerophytic vegetation |

| Centre (C) | Guanajuato, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, Estado de México, Distrito Federal, Morelos, Cuernavaca, Puebla, Veracruz, Michoacán, Guerrero | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | Pinus-Quercus forests, prairies, tropical dry forest, thorny shrubs, xerophytic vegetation, cloud montane forest, tropical rain (evergreen) and deciduous forests, aquatic and sub-aquatic vegetation |

| Southeast (SE) | Oaxaca, Veracruz, Chiapas, Tabasco and part of Campeche | Tehuantepec Isthmus, Sierra Madre del Sur, Sierra Norte de Oaxaca | Quercus forests, prairies, thorny shrubs, cloud montane forest, tropical rain (evergreen) and deciduous forests, aquatic and sub-aquatic vegetation |

| Yucatán Peninsula (P) | Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo | Shrubs, tropical rain (evergreen) and deciduous forests, aquatic and sub-aquatic vegetation |

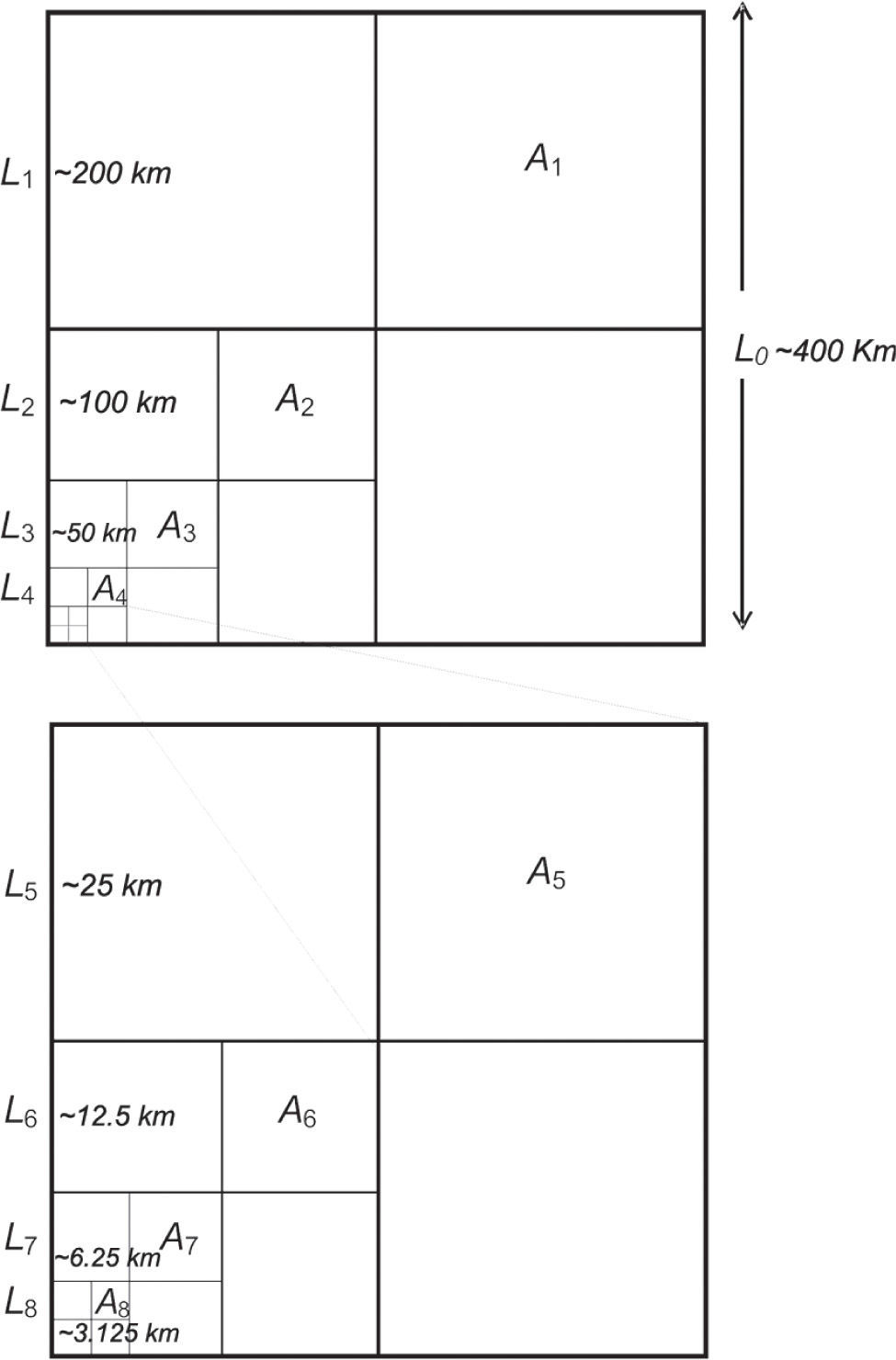

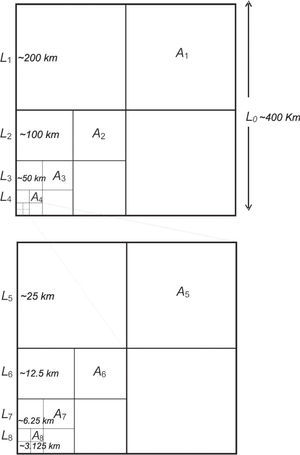

We fixed the ‘extent’ of our study (squares of 160 000km2) and varied the ‘grain’ (sensuBarton et al., 2013) as follows. Seven spatial scales were obtained by dividing the regions in successively smaller squares following the method proposed by Arita and Rodríguez (2002). Overall, it is a nested design, where the unit of study is a square, and the scales are subdivisions of the square that are progressively smaller. Following this procedure, we started with a 400 x 400km square, the coarsest region (A1); then, we subdivided it in 4 squares, 200 x 200km (A2). The next scale was constructed by subdividing each 200 x 200km squares in 4 squares, 100 x 100km, obtaining 16 squares of 100 x 100km (A3). We repeated the procedure in the next 5 scales. The finest spatial scale corresponds to 16 384 squares of 3.12 x 3.12km (A8). We subdivided the initial square 7 times, then, the scales ranged from around 160 000km2 to around 10km2 (Fig. 2).

System of nested squares designed to analyze the scaling of species diversity proposed by Arita and Rodriguez (2002). A square-shaped region of side L0 and area A0= L02, is divided into 4 squares of side Lj= L0/2 and area Aj= LJ2= AQ/22. By iterating the division i times, a series of increasingly smaller squares of side Li= L0/2i and area Ai= Li2= AQ/22 is obtained. The nested design for this study comprise a wide range of scales, as the region A0= 400 x 400km (—160 000km2) is divided 7 times: Aj= 200 x 200km (—40 000km2), A2= 100 x 100km (—10 000km2), A3= 50 x 50km (—2 500km2), A4= 25 x 25km (—625km2), A5= 12.5 x 12.5km (—156.25km2), A6= 6.25 x 6.25km (~39.06km2), A7= 3.12 x 3.12km (—9.76km2) (for clarity, the progressively finer squares are illustrated only in the lower left corners of squares)

We constructed presence-absence matrices (PAM) by intersecting all distributional maps with the set of grids in ArcView 3.2 (ESRI, 1999), and run all analyses in geographic coordinates. The intersected databases were exported to Access, performing a crosstab query to create each PAM. All steps were done for each taxonomic group and region at each spatial scale. Using PAM, we calculated the total species number for the coarsest scale (200 x 200km) and the average species number for the 7 subsequent spatial scales.

The beta diversity modelWe followed a method proposed by Arita and Rodríguez (2002), consisting in constructing ‘species-scale plots’. Details of the analytical procedure area presented elsewhere (Arita and Rodríguez, 2002), but briefly, the data required to construct the plots is the average species number (Si) at each scale, except the first point (A1) that corresponds to the total species number of the region (gamma diversity; S0). Beta diversity is the slope resulting from connecting 2 adjacent points in the plot; consequently we obtained values of beta diversity for 7 spatial scales (1-2, 2-3, 3-4, 4-5, 5-6, 6-7, and 7-8). Measured in this way, and in agreement with the system of fully nested squares, beta diversity ranges from 1 (when Si= Si _j) to 4 units (when each of the nested regions has a completely different set of species).

The model predicts that if the slope of the line connecting 2 adjacent points of the graph is constant along all the scales, beta diversity is self-similar (Arita and Rodríguez, 2002). In order to evaluate if the observed values of beta diversity differ significantly or not from the expected beta diversity, we calculated an expected value simply by dividing the total species number of the region, by the average species number at the finest scale, and dividing that value by 4 (β= (S0/S8)/4) (Arita and Rodriguez, 2002, p. 544). We generated the expected beta diversity for each taxonomic group, for the 5 regions.

We tested if there were significant differences between the observed and expected values of beta diversity using Chisquare tests. Due to the non-independence of beta diversities among spatial scales, the comparisons were performed at each spatial scale separately. The first test included all regions and all the taxa in order to obtain a general trend of beta diversity across scales. After that, in order to evaluate if each taxonomic groups followed that general trend among regions, we performed the test separately for each region. We do not include these results due the small sample size (N= 4), which can lead to inaccuracy in the tests.

For a straightforward interpretation of the results, we plotted the observed beta diversity directly in ‘beta diversity-scale plots’. In this plot, if beta diversity is self-similar, we would observe a parallel line to the X-axis.

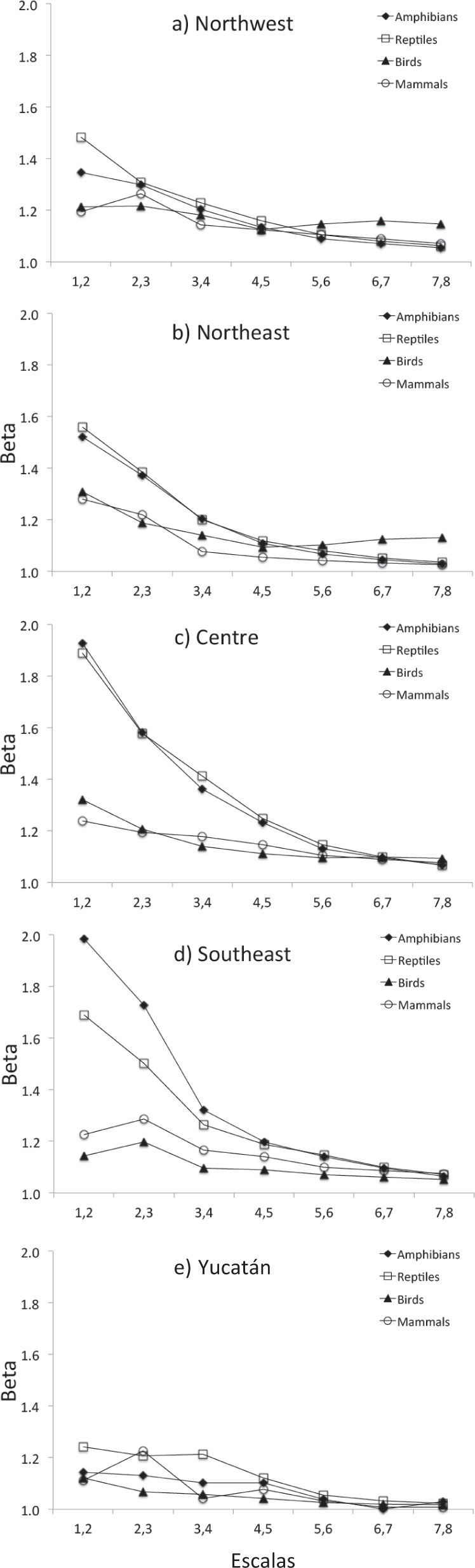

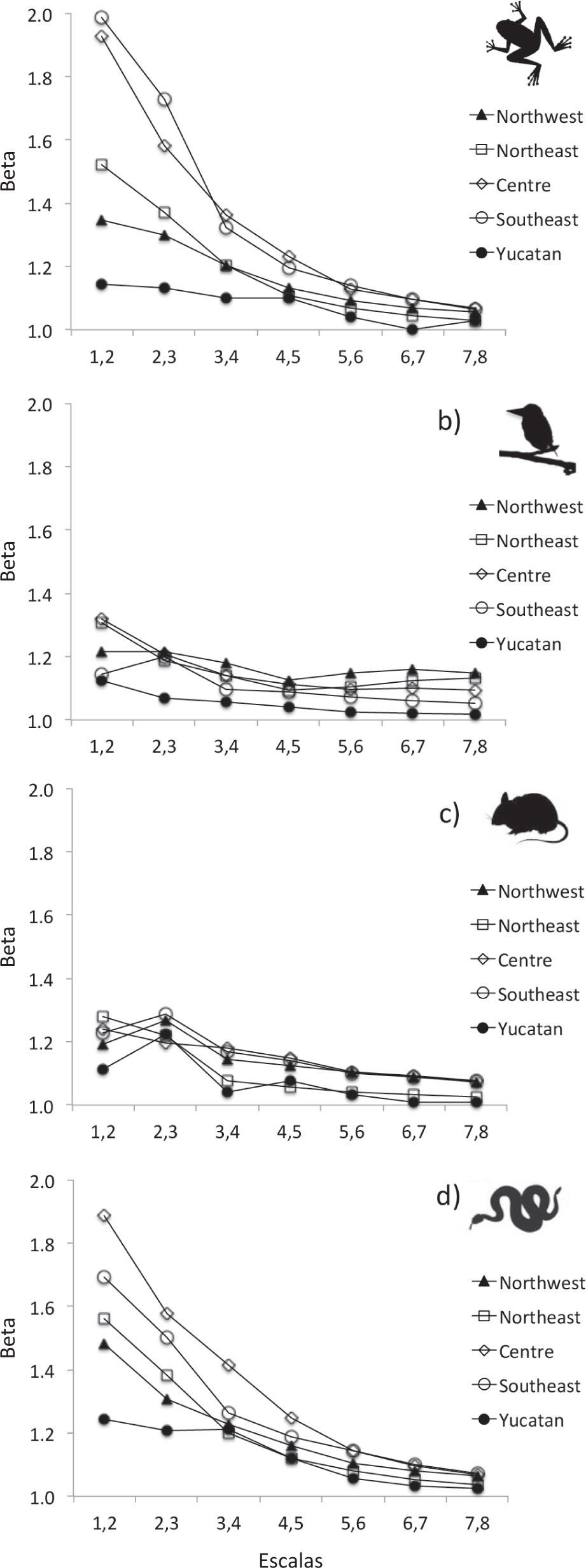

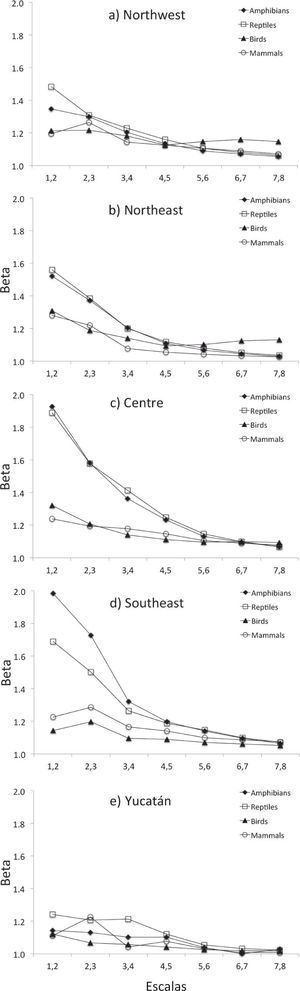

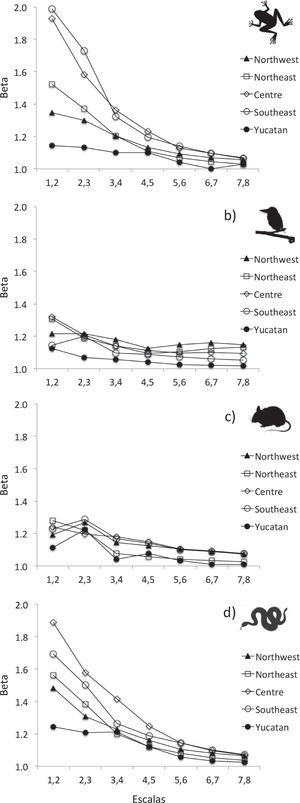

ResultsOverall, beta diversity was not self-similar across the range of scales, and the patterns varied along the scales, depending on the geographic region and the taxonomic group (Figs. 3, 4; Table 2).

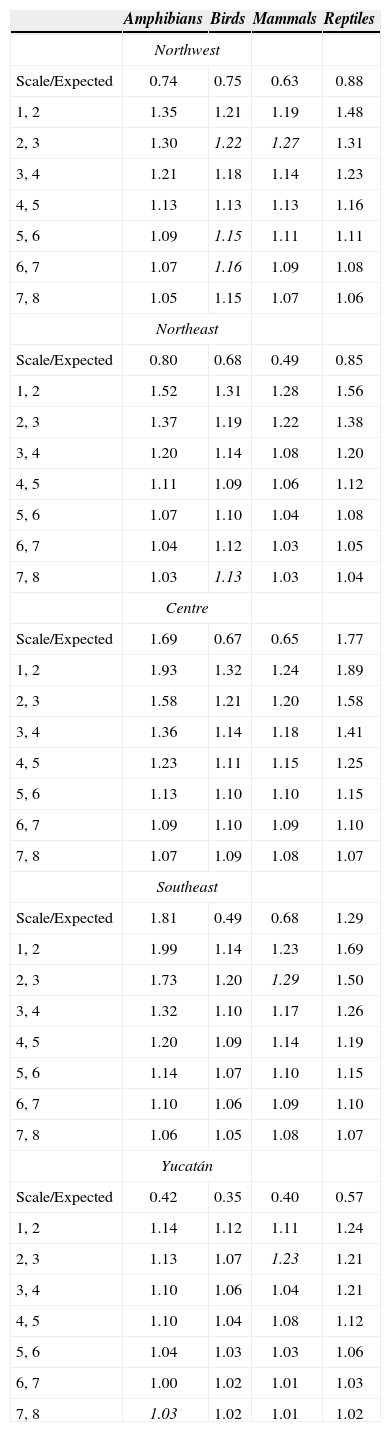

Values of beta diversity between scales. Beta diversity was calculated as the ratio of species diversity measured at adjacent scales resulting from the iterative procedure detailed in figure 2. For example 4, 5 is equal to S4average/S5average. Expected values of the self-similarity hypothesis were calculated as (S1average/S8average)/4 according to Arita and Rodríguez (2002). The highest values per scale are shown in bold and italics indicate the cases in which beta diversity resulted higher than the previous spatial scale

| Amphibians | Birds | Mammals | Reptiles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northwest | ||||

| Scale/Expected | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.88 |

| 1, 2 | 1.35 | 1.21 | 1.19 | 1.48 |

| 2, 3 | 1.30 | 1.22 | 1.27 | 1.31 |

| 3, 4 | 1.21 | 1.18 | 1.14 | 1.23 |

| 4, 5 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.16 |

| 5, 6 | 1.09 | 1.15 | 1.11 | 1.11 |

| 6, 7 | 1.07 | 1.16 | 1.09 | 1.08 |

| 7, 8 | 1.05 | 1.15 | 1.07 | 1.06 |

| Northeast | ||||

| Scale/Expected | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.49 | 0.85 |

| 1, 2 | 1.52 | 1.31 | 1.28 | 1.56 |

| 2, 3 | 1.37 | 1.19 | 1.22 | 1.38 |

| 3, 4 | 1.20 | 1.14 | 1.08 | 1.20 |

| 4, 5 | 1.11 | 1.09 | 1.06 | 1.12 |

| 5, 6 | 1.07 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.08 |

| 6, 7 | 1.04 | 1.12 | 1.03 | 1.05 |

| 7, 8 | 1.03 | 1.13 | 1.03 | 1.04 |

| Centre | ||||

| Scale/Expected | 1.69 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 1.77 |

| 1, 2 | 1.93 | 1.32 | 1.24 | 1.89 |

| 2, 3 | 1.58 | 1.21 | 1.20 | 1.58 |

| 3, 4 | 1.36 | 1.14 | 1.18 | 1.41 |

| 4, 5 | 1.23 | 1.11 | 1.15 | 1.25 |

| 5, 6 | 1.13 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.15 |

| 6, 7 | 1.09 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.10 |

| 7, 8 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 1.07 |

| Southeast | ||||

| Scale/Expected | 1.81 | 0.49 | 0.68 | 1.29 |

| 1, 2 | 1.99 | 1.14 | 1.23 | 1.69 |

| 2, 3 | 1.73 | 1.20 | 1.29 | 1.50 |

| 3, 4 | 1.32 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 1.26 |

| 4, 5 | 1.20 | 1.09 | 1.14 | 1.19 |

| 5, 6 | 1.14 | 1.07 | 1.10 | 1.15 |

| 6, 7 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.09 | 1.10 |

| 7, 8 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.08 | 1.07 |

| Yucatán | ||||

| Scale/Expected | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.57 |

| 1, 2 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.24 |

| 2, 3 | 1.13 | 1.07 | 1.23 | 1.21 |

| 3, 4 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.04 | 1.21 |

| 4, 5 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.08 | 1.12 |

| 5, 6 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.06 |

| 6, 7 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.03 |

| 7, 8 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.02 |

Beta diversity was higher at the coarsest scales (1-2, 2-3) and tended to decrease as the scale became finer in all groups. At the finest scales (5-6, 6-7, 7-8), beta diversity was relatively low for all terrestrial vertebrates (Figs. 3, 4). For example, at the coarsest scales, beta diversity of amphibians in Centre region was around 2 units; for the second-largest scales was lower (1.6 units), and at the finest scale resulted much lower (1.2 units) (Fig. 3). Overall, we observed similar trends in all the regions even in the Yucatán Peninsula region, where beta diversity was low along all spatial scales, but even lower at the finer scales.

Some exceptions to this general tendency were found in NW and NE regions, where beta diversity of the scale 23 resulted higher than the scale 1-2 for birds and mammals; in NW, beta diversity increased in 5-6 and 6-7 scales, and in NE, beta diversity increased in 7-8 scale for birds. In SE and the Yucatán Peninsula, beta diversity was higher in scales 2-3 than in previous scales for mammals. In the Yucatán Peninsula, beta diversity increased in scales 7- 8 for amphibians compared to previous scales (Fig. 3).

The results of global Chi-square tests (performed for each individual scale and including all the regions and all the groups) showed that at coarser scale, beta diversity was significantly higher that the expected: 1-2 (7.73, df= 1,p< 0.01), and 2-3 (5.52, df=1,p< 0.025). In contrast, at finer spatial scales beta diversity resulted not significantly different than expected: and 3-4 (3.07, df=1, p<0.1), 4-5 (2.18, df=1, p<0.9), 5-6 (1.65, df=1, p<0.9), 6-7 (1.41, df=1, p<0.9) and 7-8 (1.28, df=1, p<0.9), that is, it tended to be self-similar within this range of spatial scales (Table 2).

The results of individual regions Chi-square test, showed that observed beta diversity resulted higher than the expected null hypothesis in all individual cases of the NW, NW and Yucatán Peninsula. This is also the case of birds and mammals in the Centre and SE regions. In all the cases, for amphibians and reptiles the observed beta diversity resulted higher than the null hypothesis at coarser scales, but lower at finer scales (Table 2). Nonetheless, it is worth mentioning that although the values resulted higher than the null hypothesis, at lower scales the values were not significantly different according to the Chi-tests.

Reptiles and amphibians showed the highest beta diversity in most of the regions and scales, and resulted particularly notorious at coarser scales (Fig. 3). Some few exceptions were found, for example, birds showed higher beta diversity than reptiles and amphibians in NW region, in the scales 5-6, 6-7 and 7-8 in NW. When we compare the beta diversity between mammals and the birds, we obtain mixed results: mammals tended to show higher beta diversity than birds in the Centre region (at spatial scales 3-4, 4-5, 5-6, 6-7 and 7-8), and in SE and the Yucatán Peninsula region (scale 2-3) (Fig. 3).

DiscussionSelf-similarity patterns of diversity have been associated to a single process driving the scaling of diversity. Conversely, a non-self-similar pattern implies more than one driving process in the scaling of diversity (Crawley and Harral, 2001; Drakare et al., 2006). Our results provides further solid evidence that beta diversity is scale dependent in all terrestrial vertebrates in Mexico; at coarser scales, beta diversity is high, but decreases as spatial scales decreases, consequently different processes that acts at different scales are explaining the beta diversity of Mexico.

Beta diversity is higher at coarse scalesHigh beta diversity at coarser spatial scales was observed for all groups of terrestrial vertebrates and was significantly different from the expected null hypothesis. Larger spatial scales of 2° grids (~40 000km2) likely include different vegetation types, ecoregions, and unrelated biota assemblages with contrasting biogeographic histories (Crawley and Harral, 2001; Sánchez-Cordero et al., 2005; Drakare et al., 2006; Barton et al., 2013). Thus, the trend of high beta diversity at coarse spatial scales is likely a result of a complex interplay of habitat heterogeneity, contrasting types of vegetation and biogeographic histories as area increases (Crawley and Harral, 2001; Drakare et al., 2006; Barton et al., 2013). Exceptionally high values were found in the Centre and SE, both of these regions fall within the ‘Mexican Transition Zone’ defined by Halffter (1987), a highly complex area where the Neotropical and Nearctic realms overlap. This supports the previous argument of different biogeographic histories generating high values of beta diversity.

According to previous studies (Koleff et al., 2008), beta diversity of amphibians and reptiles tended to be significantly higher than for mammals and birds. In general, low dispersal capacity and the small distributional range of the species of these groups (Ochoa-Ochoa and Flores-Villela, 2006) explains the extraordinary high beta diversity, particularly at the coarse scale. Indeed, amphibians showed the highest beta diversity in the Centre and SE regions, being congruent with the fact that in those regions amphibians have the smallest range size. Conversely, reptiles showed the highest beta diversity in NW, NE and the Yucatán Peninsula, where they have restricted distributional range sizes, in congruence with the biogeographical history and the endemism pattern of reptiles in Mexico (Marshall and Liebherr, 2000; Ochoa-Ochoa and Flores-Villela, 2006; Ochoa-Ochoa et al., 2014).

Contrarily to the pattern reported in previous analyses (Koleff et al., 2008), birds showed higher beta diversity than mammals in all the regions, except in SE. We find these results counter-intuitive, but provide a preliminary explanation. It is possible that the distributional ranges of birds tend to be ecoregion-restricted (Vázquez et al., 2009), whereas mammals can occur in 1 or more ecoregion included in the region. An alternative, but not mutually exclusive explanation, is that the relatively low beta diversity of the mammals is due to the effect of volant mammals which were not excluded from the analyses. Bats have significantly larger distributional range sizes compared to non-volant mammals (Arita, 1997). For example, it is well documented that rodents show restricted non-overlapped distributions along the western, central and eastern regions of the Transvolcanic Belt (e. g., Sánchez-Cordero et al., 2005; Escalante et al., 2007; Navarro-Sigüenza et al., 2007).

The highest beta diversity values for terrestrial vertebrates occurred in the SE region (amphibians), and Centre (birds, reptile and mammals). The SE region includes the southernmost part of the Sierra Madre Oriental, a region that holds a complex topography with highly diverse plant associations (Table 1), as for example the montane cloud forest. This type of forest contains the highest diversity of birds partly due to an exceptional number of endemism and ecologically restricted bird species in Mexico (Escalante-Pliego et al., 1998; Sánchez-González and Navarro-Sigüenza, 2009). This region has been also identified as a centre of endemism for amphibians and reptiles (Ochoa-Ochoa and Flores-Villela, 2006, 2011). The fact that amphibians always have higher beta diversity than birds, even though the former have lower gamma diversity (i. e., 148 species in SE) than the latter (433 species), does not support the idea that the higher the species richness, the higher beta diversity as reported in other studies (Gaston et al., 2007). The restricted range size of the species of amphibians that inhabit the SE region explains the extraordinary high beta diversity of this group. In other words, beta diversity is not directly associated to the species richness per se but to the size of the distribution areas.

The lowest beta diversity values at coarse spatial scales observed in the Yucatán Peninsula for all terrestrial vertebrates can be explained as the ‘Yucatán Peninsula effect’, that is the tendency of the species to have large range sizes. Indeed, in this region, the proportion of the distributional ranges between groups tend to be large (Vázquez-Domínguez and Arita, 2010; e. g., Cortés-Ramírez et al., 2012, for birds; Lee, 1980, for amphibians and reptiles; Arita and Vázquez-Domínguez, 2003, for mammals), likely as a consequence of the low environmental heterogeneity, similar vegetation types (Ibarra-Manríquez et al., 2002; White and Hood, 2004), topography and its relatively recent history (Ward et al., 1985). The species tend to occupy a high proportion of the Yucatán Peninsula, and as a consequence, beta diversity tends to be low, as previously reported for mammals (Arita and Rodríguez, 2002).

Beta diversity is lower at finer scalesBeta diversity was low at finer spatial scales for all terrestrial vertebrates. Further, beta diversity was, in general, higher but not significantly different from the expected null hypothesis, that is, it tended to be self-similar but with higher values.

At these spatial scales, the pattern of beta diversity ranging: mammals> birds> reptiles> amphibians, does not hold in all the regions. Surprisingly, at finer spatial scales, birds showed the highest beta diversity values among terrestrial vertebrates in NE, NW, and the Centre. This unexpected trend can be explained as an artifact due to the fact that only resident birds were considered in the study. The distribution of the resident birds limits in both NE and Centre regions and, as a consequence, at finer spatial scales several sites do not contain species, mirroring in low mean alpha diversity and then in high beta diversity.

Our results suggest that at finer scales (beyond 2 500km2; 0.5° lat-long) beta diversity is more influenced by ecological than historical factors (Crawley and Harral, 2001; Barton et al., 2013). The ecological interactions and dynamics are probably more related to the complex topography of the country (Ferrusquia-Villafranca, 1993). Environmental heterogeneity allows different vegetation types to share a reduced geographical region; however, the effect of environmental heterogeneity depends on the taxa and the scale. For example, a landscape unit from the human perspective may be defined from 30 to 300km2 (Fischer and Lindenmayer, 2007), for an amphibian it is probably around 100km2 (Gardner et al., 2007), but for a beetle a landscape unit can be restricted to a few square meters (Wiens and Milne, 1989). Differences in the patterns of diversity between taxonomic groups could be associated with species’ different spatial scale perceptions of environmental heterogeneity.

Other possible factors that explain beta diversity at fine scales come from the Species-Area relationship (SAR) topology. Recently, Triantis et al. (2012) showed that when the spatial range analyzed exceeds 3 orders of magnitude (as does this study ~10km2 to 160 000km2), SAR are best represented by a sigmoid curve (Lomolino et al., 2010) with 3 main slopes with different values, equivalent to different values in beta diversity. Factors proposed to explain this pattern referred as “small-island effect” (Lomolino and Weiser, 2001), are resources availability, dispersal abilities, and degree/time of isolation. Some of these factors might contribute to the fact that the Centre and SE regions have a high proportion of endemic and range restricted species, increasing the possibility of recording high beta diversity.

The low beta diversity at finer spatial scales can also be explained as an extension the ‘Yucatán Peninsula effect’, mentioned above, that is the tendency of the species to have large range sizes. At the finer scales (i. e., squares of 3.12 x 3.12km, 6.25 x 6.25km, 12.5 x 12.5km), the species tend to occupy a high proportion of the squares in which the region was subdivided, mirroring in low values of beta diversity in all the groups.

At these finer spatial scales, an additional and related explanation to the effect describe above is proposed. The sources of information used in our study (species range distribution generated using climatic niche models) are restrained by the spatial autocorrelation of the environmental variables used for producing species distribution models. Thus, distributions tend to over-fill areas, whereas at a landscape scale, distributions would be more fragmented. It is possible that some of the detailed habitat preferences are not captured by our modeling approach resulting in an underestimation of beta diversity values. We assumed that all terrestrial vertebrates are affected similarly at finer scales, which is highly unlikely.

Scale dependence of Beta diversityThis study provides further solid evidence that beta diversity is scale dependent in all terrestrial vertebrates in Mexico; at coarser scales, beta diversity is high, but decreases as spatial scales decreases. Scale dependency of beta diversity was also observed by Lira-Noriega et al. (2007) with the resident avifauna of central Mexico. As far as we know, there are no other studies attempting to analyses beta diversity for all of Mexico and along the large range of scales considered in this study.

In contrast to the pattern found here, other studies reported the opposite pattern, that is, lower beta diversity at coarse scales (Vellend, 2001; Qian, 2009; Qian and Ricklefs, 2000, 2012; Keil et al., 2012; Calderón-Patrón et al., 2013). Keil et al. (2012) reported that dissimilarity decreases when increasing spatial scale using dissimilarity/ distance metrics with plants, birds, herps and butterflies in Europe. In a study situated in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, southern Mexico, for vertebrates, Calderón-Patrón et al. (2013), reported higher values of dissimilarity at fine grain, while a coarse grain returns lower values of dissimilarity. The apparent contradiction of the results can be explained mainly by differences in conceptual terms and, in consequence, in the methods applied to measure beta diversity. The studies that focus on the ‘differentiation’ aspect of beta diversity (Tuomisto, 2010; Moreno and Rodríguez, 2010, 2011) use indices based on the dissimilarity/distance family. The number of species shared between 2 squares increases as the resolution decreases (i. e., larger areas), and occurs mainly because larger areas have more species or because the degree of aggregation of species is reduced (Gaston et al., 2007). In contrast, when the study of beta diversity is focused in the ‘proportional’ aspect of beta diversity (Moreno and Rodríguez, 2010), the indices used are, for example, the Species- Area relationship (the method used in this study is based on the SAR). Scale in this case is the size of the area and, the slope of the SAR unavoidably became steeper with increasing the area (i.e. scale), or, as the exception found in this study, in the Yucatán Peninsula, practically z does not increases with increasing the area.

Implication for conservation of biodiversityOur results suggest that the spatial scale to perform complementarity analysis for conservation purposes needs to be taken into consideration. Overall, there is a break in the values of beta diversity at the spatial scale 4-5 (from 50 x 50km to 25 x 25km), where beta diversity decreases drastically and become similar along the remaining finer spatial scales. Thus, the optimal scale to capture the maximum dissimilarity across communities using models of species distributions are squares of 625km2.

Large protected areas are more suitable for conservation, such as Calakmul or Sian Ka’an in the Yucatán Peninsula; conversely, conservation area networks are more suitable in regions holding high beta diversity, as in the Centre or SE regions. Moreover, recent approaches of rarity-complementarity for selecting priority areas for conservation of terrestrial vertebrates can be adjusted to an adequate spatial scale as proposed in our study.

This study presents the first set of analyses of beta diversity across a wide range of 7 spatial scales (from ~160 000km2 to ~10km2) for the Mexican terrestrial vertebrates. The simultaneous analyses for 5 different regions allowed us to make suggestions about the generality of the pattern of scaling of beta diversity and, more importantly, to generate specific predictions regarding the factors that might explain the patterns of diversity in Mexico.

Our study showed that beta diversity varies among regions and spatial scales, suggesting some processes that act differentially between spatial scales and taxonomic groups. Drivers of beta diversity vary along spatial scales, and both historical and ecological processes shape the patterns of biological diversity of vertebrates of Mexico. At coarser spatial scales, complex interplay of habitat heterogeneity, contrasting types of vegetation and biogeographic histories as area increases seem to be important to explain the extraordinary beta diversity, whereas, in turn, at finer spatial scales ecological processes related to topography, environmental heterogeneity and in general the local environmental conditions seem to be the important to explain the beta diversity. Also, the information used in the study (niche models) and other decisions, such as considering resident birds only, might also affect the results.

Beta diversity of each group contributes to the megadiversity of Mexico in different ways. Amphibians and reptiles are important at coarse scale, whereas, surprisingly, birds contribute to high values of beta diversity at finer scales. The general pattern of beta diversity found at the scale of 2 500km2 following the dispersal capacity of the 4 groups, amphibians > reptiles > mammals> birds (Koleff et al., 2008), does not hold at other scales, opening new and interesting question to be investigated.

Findings of this study set the basis for more elaborated hypotheses that need to be tested regarding the biogeographic affinity of these taxonomic groups in spatially explicit ways, and with respect to the environments in which their species occur. Finally, our study may help to determine the spatial scale which is better suited for the assessment and design of protected areas in the context of the diversity patterns of the 4 taxonomic groups evaluated.

AcknowledgmentsL. Ochoa-Ochoa, A. Lira-Noriega and M. Munguía doctoral studies’ were supported by Conacyt, L. Ochoa- Ochoa was also supported by SEP, and currently is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from DGAPA- UNAM. We are very thankful for the support and technical assistance of many people and institutions, particularly to the Lab of Geospatial Analyses from the Instituto de Geografía (UNAM). We are grateful to Rafa de Villa Magallón and R. J. Whittaker for their helpful advice and comments. We are thankful to Ella Vázquez and one anonymous reviewer for their comments that helped to improve this manuscript.