To determine the degree of apical root resorption of the upper and lower anterior and posterior teeth (except molars) in orthodontically treated patients of the Orthodontics Department of the Postgraduate Studies and Research Division of the Faculty of Dentistry at the National University of Mexico (UNAM) whose treatment was finished during 2010-2012.

MethodOut of 1,125 files, fifty-five that met the criteria were selected. One of the criteria was that the files included pre and post-treatment panoramic radiographs taken with the Radiology Department's panorex. Information related with treatment was obtained such as: extraction or non-extraction treatment, treatment duration and employed technique. In all digital pre and post-treatment panoramic radiographs, the total length and the crown length of all teeth except molars were measured. The obtained data was gathered on a database to apply a formula for apical rooth resorption analysis.

ResultsUpon comparison of the mean apical root resorption it was observed that the most affected teeth were the lower central incisors followed by the upper lateral incisors. The teeth with the least amount of apical root resorption were first premolars. No association was found between the apical root resorption and extractions, employed technique and apical root resorption, gender and apical root resorption variables (p > 0.05).

ConclusionsAll teeth exhibited apical root resorption to some degree. Apical root resorption did not increase in extraction treatments in regard to non-extraction treatments. No genderrelated preference for apical root resorption was found. There was a positive correlation between sliding mechanics and apical root resorption.

Determinar el grado de reabsorción radicular de dientes anteriores y posteriores (excepto molares), superiores e inferiores en pacientes tratados en el Departamento de Ortodoncia de la División de Estudios de Postgrado e Investigación de la Facultad de Odontología de la UNAM, terminados en el periodo 2010-2012.

MétodoDe 1,125 expedientes se seleccionaron 55 que cumplieron con los criterios, uno de los cuales era que contaran con ortopantomografías pre- y post-tratamiento tomadas con el ortopantomógrafo del Departamento de Radiología. Asimismo, se recolectó información relacionada con el tratamiento: extracciones versus no extracciones, duración del tratamiento y técnica empleada. En todas las ortopantomografías digitales pre- y post-tratamiento se midió la longitud total y la longitud coronal de todos los dientes, excepto molares. La información se asentó en una base de datos para aplicar una fórmula para el análisis de reabsorción radicular.

ResultadosAl comparar el promedio de reabsorción radicular se observó que los incisivos centrales inferiores fueron los más afectados, seguidos por los incisivos laterales superiores. Los que presentaron menor cantidad de reabsorción radicular fueron los primeros premolares. No se encontró asociación entre las variables reabsorción radicular y extracción dentaria, técnica empleada y reabsorción radicular; sexo y reabsorción radicular (p > 0.05).

ConclusionesTodos los dientes presentaron reabsorción radicular en algún grado. No existe mayor grado de reabsorción radicular en el tratamiento de Ortodoncia con extracciones, respecto al tratamiento sin extracciones. No existe predisposición de género a la reabsorción radicular. Existe mayor riesgo a desarrollar reabsorción radicular en mecánicas radicular en mecánicas ortodóncicas de deslizamiento.

Sometimes, orthodontic treatment causes adverse effects that must be avoided or minimized; in order to do this, they must be identified timely to prevent its progress or that they might become irreversible.

Among orthodontic treatment adverse effects, there is the diminishment of the root length which is named root resorption (rr). It is associated with the application of forces on the teeth. In most cases only a slight root length reduction is present and it is not clinically significant; however, when rr is more severe, it compromises tooth stability.

RR identification, monitoring and management is of outmost importance in the orthodontic patient; as well as it is the orthodontist's responsibility to understand the mechanisms involved in this phenomenon.

BACKGROUNDForce application on a tooth to produce its movement has some risks, one of which is external rr. It consists in the decrease or shortening of the radicular apex1 which is a pathological process initiated by an external stimulus that progresses from the cement into the dentin and affects the external or lateral surface of a tooth.2

RR is classified as follows:

- a.

Of the surface. It is a self-limiting process that involves small areas of the root surface, where spontaneous repair occurs.

- b.

Inflammatory. Presence of multinucleated cells that colonize surfaces devoid of cement and reabsorb the dentin. It is divided into: (1) Transient. Occurs when the damage is of little magnitude or duration, usually the resulting defect is not detected radiographically and is quickly repaired; 2) Progressive: it is produced by stimuli that last for long periods.

- c.

Due to replacement. It occurs as a result of an extensive necrosis of the periodontal ligament with bone formation on the surface of the root. Bone slowly replaces the lost cement of the root surface and joins the remaining cement producing ankylosis.

Forces that are generated and transmitted in Orthodontics cause a resorption of the surface, the inflammatory, transient type.2

The first descriptions of root resorption were made by Pierre Fauchard with Orthodonticfixed appliances in the seventeenth century; but it was not until 1856, when Bytes3 mentioned rr in a permanent dentition. In 1914, Ottolengui reported the direct relationship betweenorthodontic treatment and root resoprption.4

Etiology is multifactorial and depends of individual biological characteristics, genetic predisposition, and orthodontic forces.5,6Risk factors may be categorized according to those who are patient-related or biological factors, among which there are: genetic factors7 systemic factors,8–10 age,2 nutritionalstatus,11 gender,12 ethnic group,13 medications,14,15 dentoalveolar structure,16,17 habits;18 dental morphology, size and number;17 tooth vitality,2 previous root resorption,11–23 previous dentoalveolar trauma,24 periapicalinfections,16 occlusal factors25 and specific vulnerability to the rr.15

There are also factors related to orthodontic treatment or mechanical factors which are: appliance type, 26 types of movement, 27 force kind and extent,17 treatment duration,28 severity, and type of maloclussion.17,29

RR diagnosis in Orthodontics is performedby means ofradiographs before, during and at the end of the treatment19,30,31 (6-9 months). Once the appliances are placed, it is advisable to check for rr.30,32 In those teeth with an increased risk such as teeth with blunt or pipette-shaped apex, radiographic studies every three monthsare recommended. In order to be able to compare different radiographs these have to be taken with the same radiographic technique and with a standardized method, because this is the only way in which they can be checked against.32 The main clinical implication is mobility of the affected teeth and the resulting susceptibility to occlusal trauma.33,34

There are 4 severity degrees of root resorption:35,36 in degree #1 anirregular contour root may be observed; in degree #2 there is a root shortening that does not exceed 2mm of the root's length; in degree #3 rr is between 2mm or 1/3 of the root's length; and in degree #4, root loss is more than 1/3 of the root. Without doubt, grade 4 has the worst prognosis according to the classification of Levander (1988).

It is known that the progression of lesions caused by orthodontic forces, once the appliances are removed, stabilizes. Even ten years after the end of the orthodontic treatment the amount of root loss estimated in the beginning does not increase.33,37

OBJECTIVESGeneral objectiveTo determine the degree of rr in anterior and posterior teeth (excluding molars) in patients treated at the clinic of the Orthodontics Department of the Postgraduate Studies and Research Division who finished treatment between 2010-2012.

Specific objectives- •

To determine the degree of rr in incisors, canines and upper and lower premolars in patients treated at the clinic of the Orthodontics Department who finished treatment in the 2010-2012 term.

- •

To determine if there is an association between rr and tooth extraction in patients treated in the Orthodontics Department during the 2010-2012 period.

- •

To determine if there is an association between the appliance prescription (Roth, MBT) and rr in patients treated in the Orthodontics Department between 2010-2012.

- •

To determine if there is an association between gender and rr in patients treated in the Orthodontics Department who completed treatment in the period 2010-2012.

The present study was conducted at the Division of Postgraduate Studies and Research of the Faculty of Dentistry of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The information was obtained from the clinical records of patients who were treated and discharged in the period 2010 to 2012. The type of study was retrospective.

1,125 Records were reviewed of which 55 were selected because they met the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria- 1.

Digital panoramic radiographs of patients treated in the Orthodontics Department who completed their treatment (with or without extractions) between the 2010-2012 period. All pre- and post-treatment panoramic radiographs were taken with the G5 Orthophos Ortopantomograph (Sirona Dental Systems, Austria) at the Department of Imaging.

- 2.

I-PP cephalometric measurement of 70 ± 5°.

- 3.

IMPA cephalometric measurement of 95° ± 5°.

- 4.

Complete permanent dentition.

- 5.

ANB angle of maximum 5° (class II, class III).

- 6.

No previous periodontal therapy.

- 1.

Records that did not meet the inclusion criteria.

- 2.

Severe skeletal discrepancy (ANB > 5°).

- 3.

Previous orthodontic treatment.

- 4.

Root canal treatments.

- 5.

Patients with a history of trauma.

The reason for selecting records of patients who finished until 2012 was due to the fact that the ortopantomograph was changed in 2013.

Demographic information such as: name, age and sex was collected; as well as information related to the treatment, e.g.: extractions vs not extractions, duration of treatment (in months) and technique used.

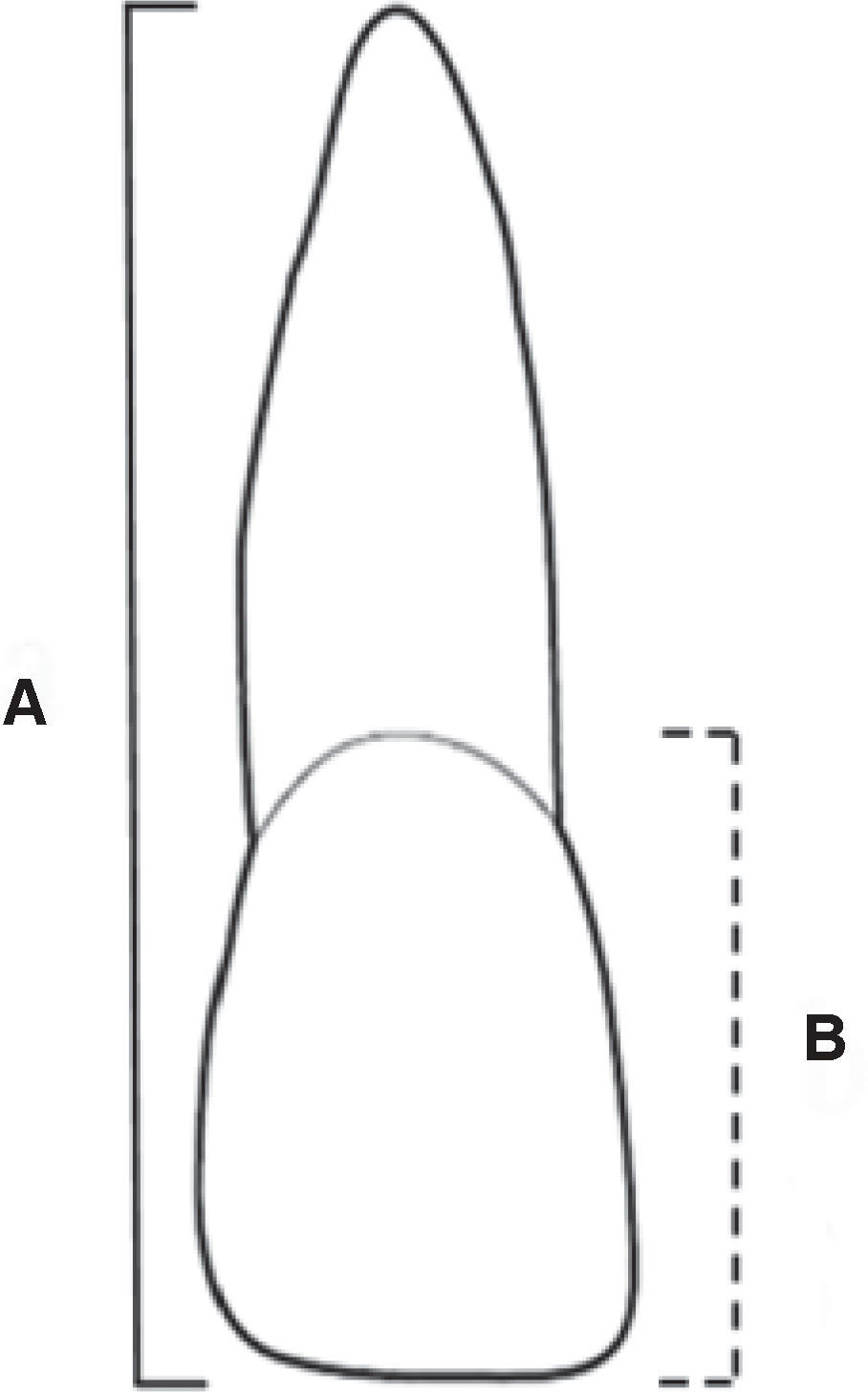

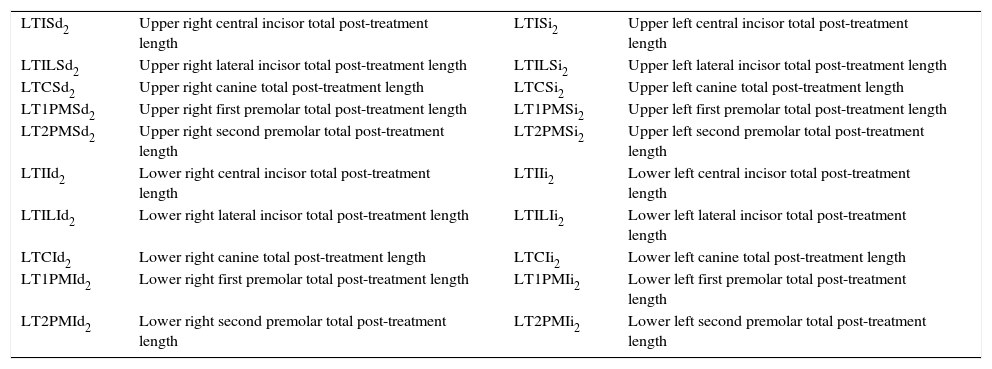

In all pre and post treatment digital panoramic radiographs, the total length and the crown length of all teeth excluding molars (Figure 1) was measured by means of the 1.51 Sidexis program (Sirona Dental Systems, Austria).

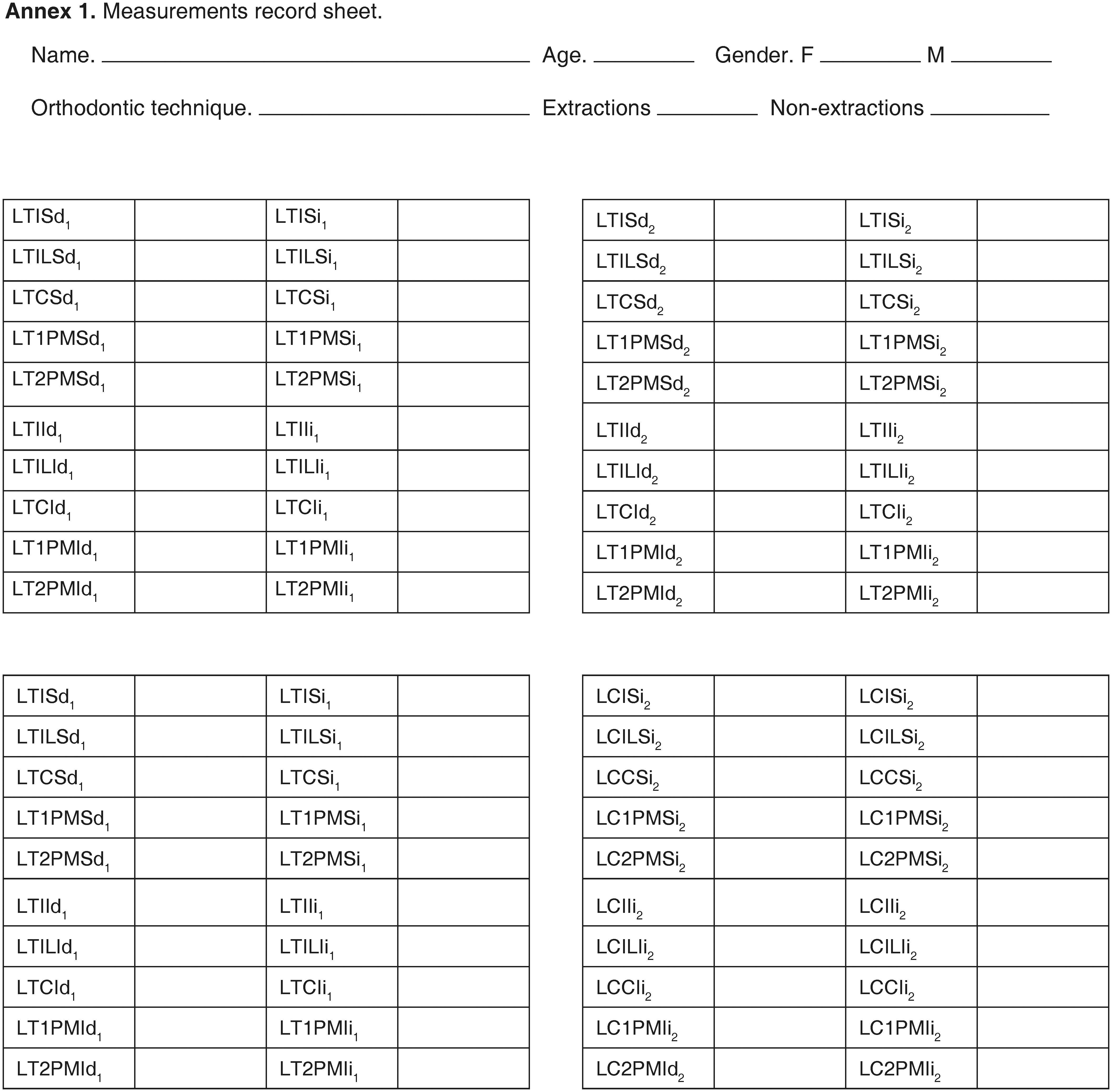

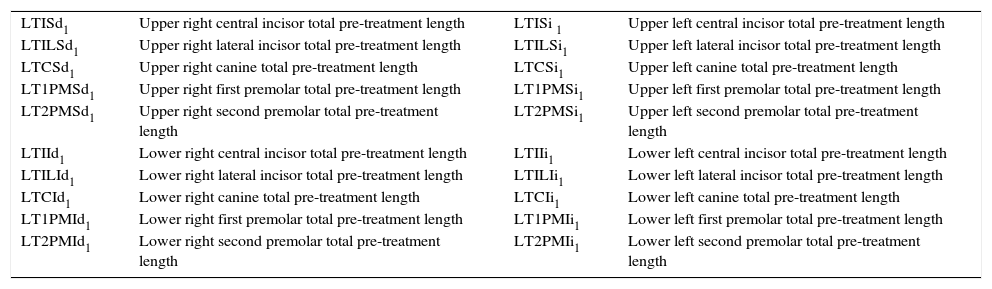

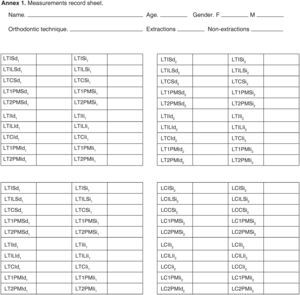

The data were transferred into a recording sheet for each patient (Annex 1) on which an identification code for each one of measurements made per tooth was assigned (Annex 2).

Subsequently, the information was recorded in a database to apply the formula proposed by Linge18 for rranalysis in panoramic radiographs, which was performed on the selected pre- and post-treatmentdigital panoramic radiographs in order to reduce magnification.

The formula proposed by Linge18 is the following:

RR = LT1(X)-LT2(X) x (C1(X)/C2(X))

RR = Root resorption.

TL1 = Pre-treatment total length.

TL2 = post-treatment total length.

C1 = Pre-treatment crown length.

C2 = Post-treatment crown length.

X = Obtained measurements

RR is the result of the product of the difference between pre-treatment total length and the posttreatment total length, and the quotient that results from dividing pre-treatment crown length between the post-treatment crown length.

RESULTSThe obtained datawere analyzed using the statistical program SPSS 18 (IBM Company, Hong Kong). Results are shown in descriptive form as means and standard deviations.

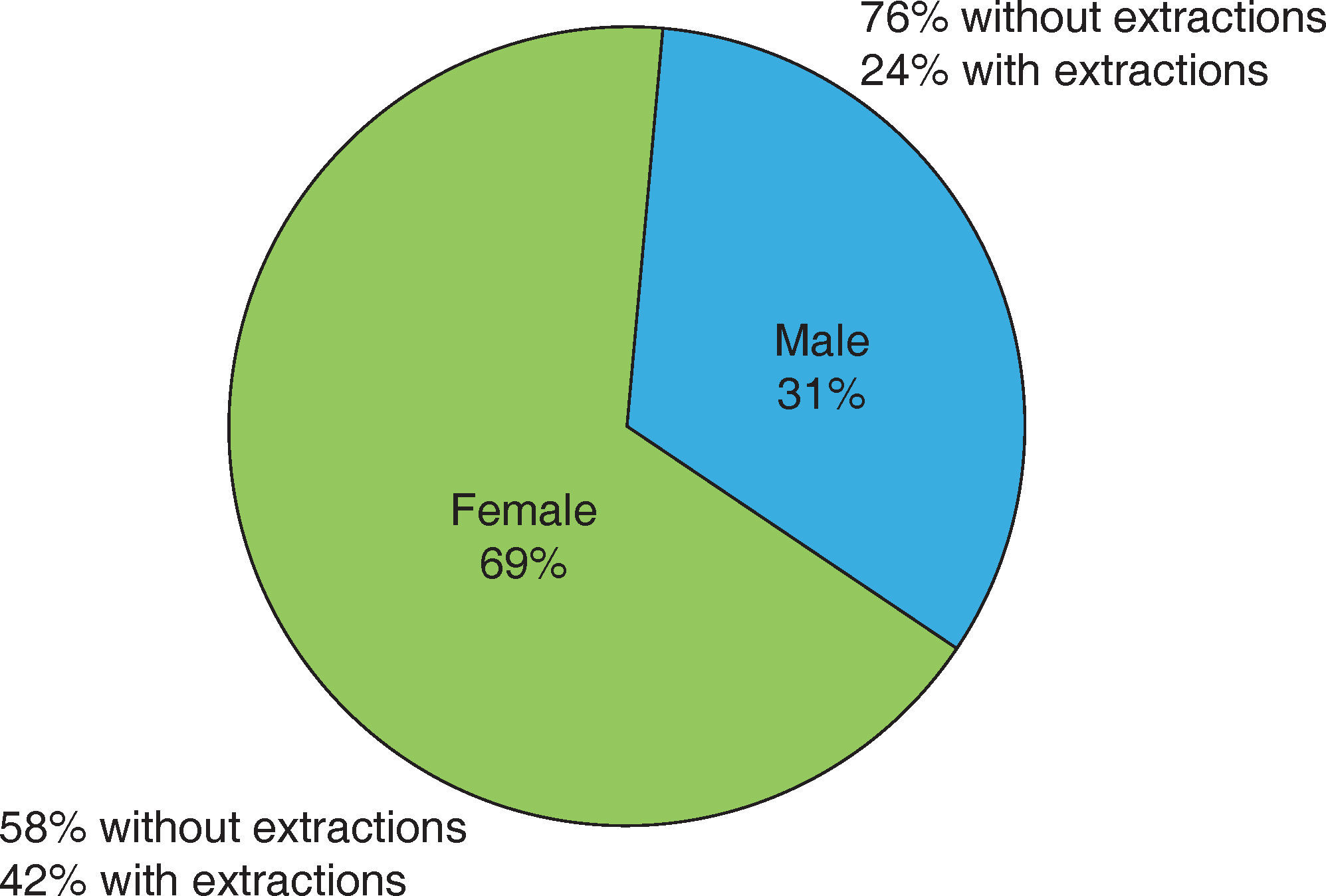

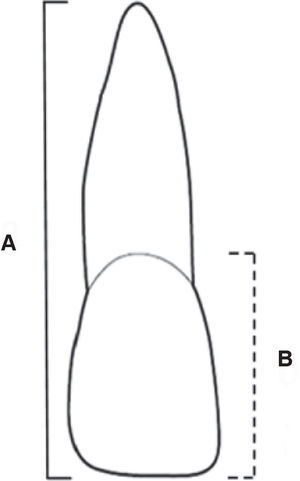

Percentage distribution by gender and treatment with or without extractionsOf the total number of reviewed files, 69% were females and 31% in males (Figure 2); the average age was 20.6 years (SD = 4.8).

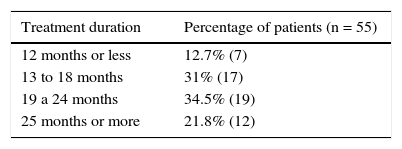

Treatment duration in monthsIt was observed that for the majority of patients treatment time was longer than 19 months (Table I).

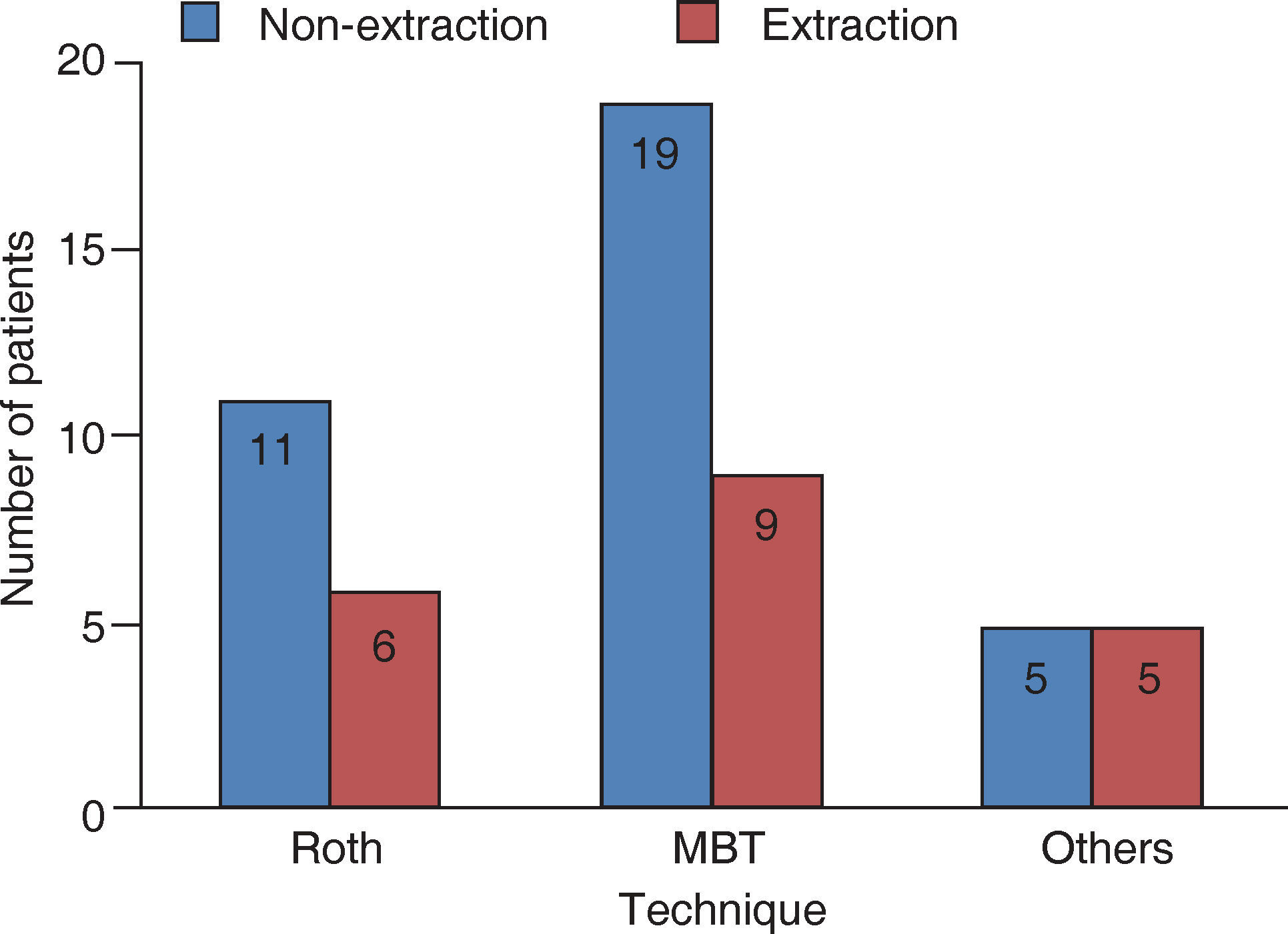

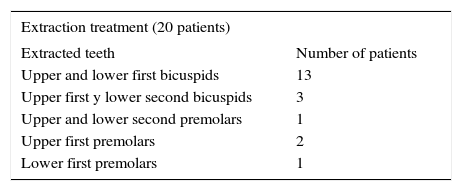

Extraction or non-extraction treatmentTreatments with extractions were a total of 20 and 35 cases were non-extraction. It was noted that the most common extraction protocol was upper and lower first bicuspids (Table II).

Patient distribution according to the selected teeth for extraction.

| Extraction treatment (20 patients) | |

|---|---|

| Extracted teeth | Number of patients |

| Upper and lower first bicuspids | 13 |

| Upper first y lower second bicuspids | 3 |

| Upper and lower second premolars | 1 |

| Upper first premolars | 2 |

| Lower first premolars | 1 |

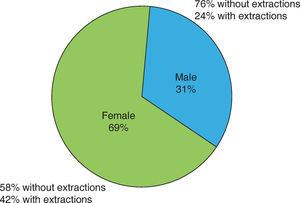

Most treatments were performed without extractions and with MBT technique (Figure 3).

Root resorption per toothIn general, all patients presented rr and all teeth were affected in a greater or lesser degree.

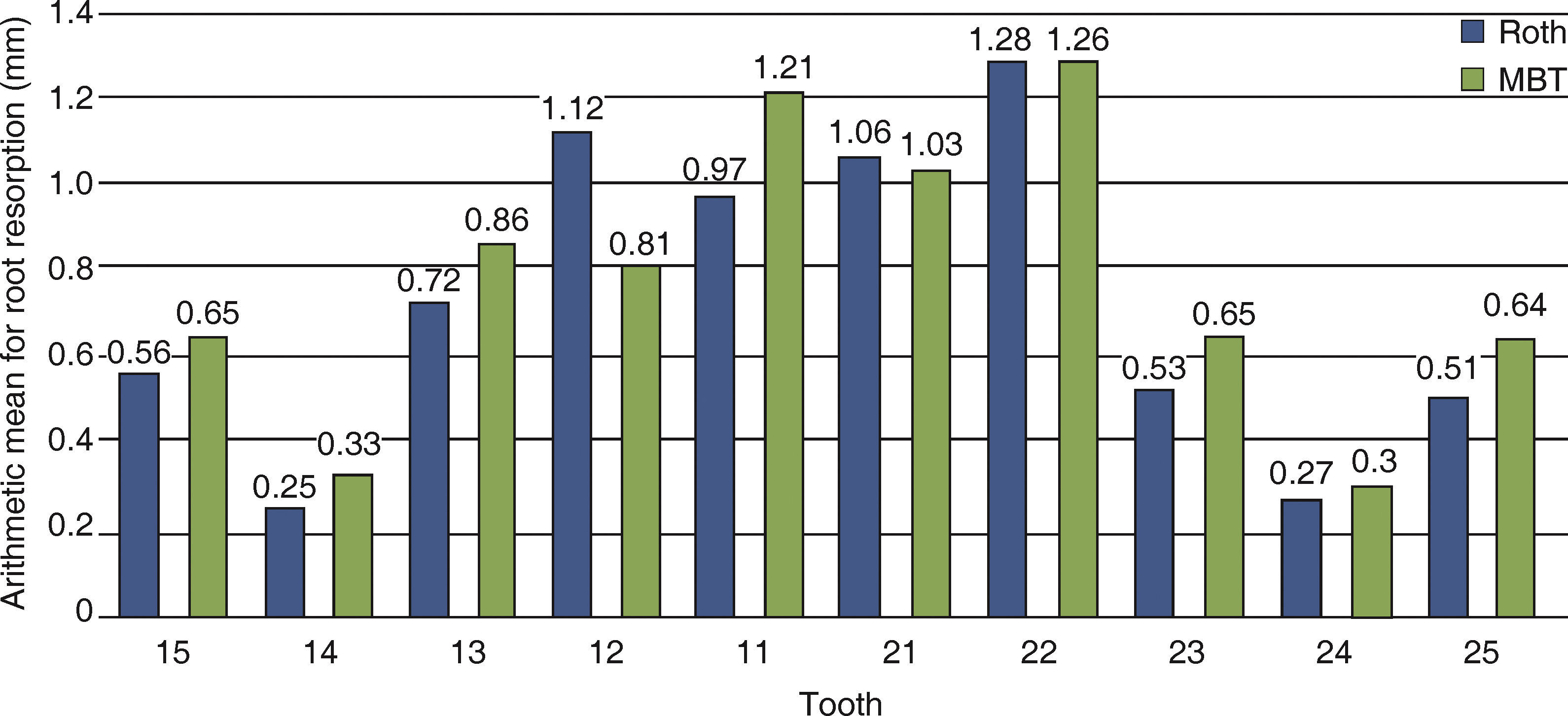

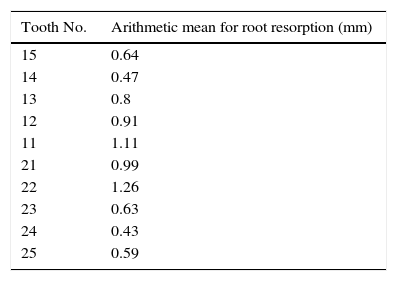

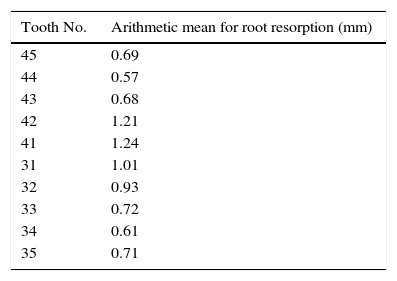

In the upper teeth, the upper left lateral incisor was the most affected by rr (Table III).

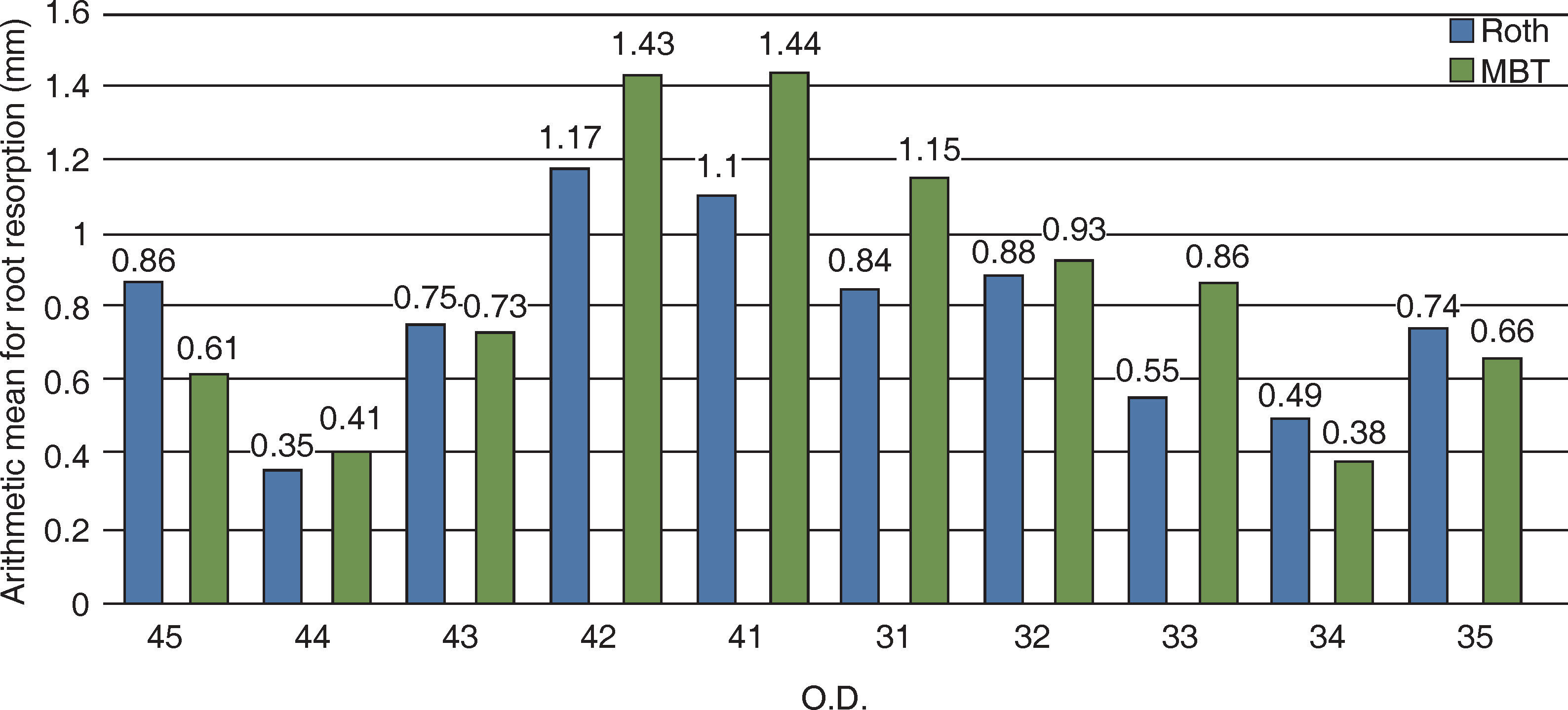

Regarding the lower teeth, the one that presented more rr was the lower right incisor (Table IV).

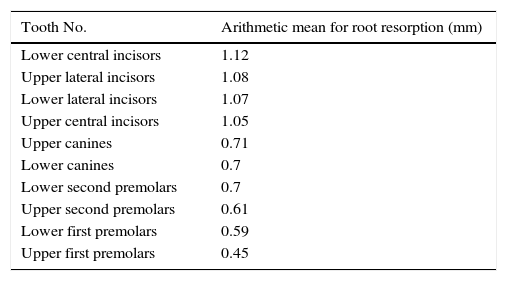

When comparing the rr average of both the upper and lower teeth, it was observed that the lower central incisors were the most affected, followed by the upper lateral incisors, with the lowest amount of rr in the upper and lower first premolars (Table V).

Arithmetic mean of rr in upper and lower teeth listed from most affected to least affected.

| Tooth No. | Arithmetic mean for root resorption (mm) |

|---|---|

| Lower central incisors | 1.12 |

| Upper lateral incisors | 1.08 |

| Lower lateral incisors | 1.07 |

| Upper central incisors | 1.05 |

| Upper canines | 0.71 |

| Lower canines | 0.7 |

| Lower second premolars | 0.7 |

| Upper second premolars | 0.61 |

| Lower first premolars | 0.59 |

| Upper first premolars | 0.45 |

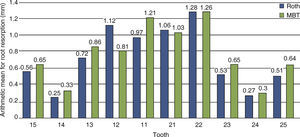

By identifying which teeth presented the highest values of rr in relation to the orthodontic technique that was used, it was observed that the upper incisors were the most affectedin both techniques, and that the least affected teeth were the first premolars (Figure 4).

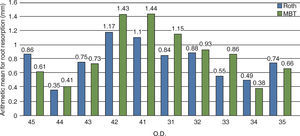

In the lower arch, more rr was present in the lower incisors with MBT appliances, especially in the right central and lateral incisors (Figure 5).

AssociationThe association between the variables was determined; in statistics it is the intention to observe the extent to which two phenomena are related in order to see whether or not there is a direct relationship between rr and certain specific factors.

The following results were observed:

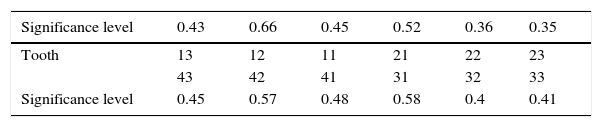

Table VI shows the significance level obtained for each tooth when calculating the association between the variables rr and tooth extraction. It should be observed that no significant difference was found (p > 0.05).

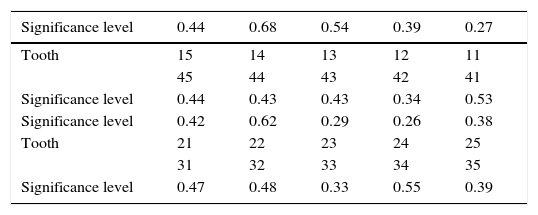

Table VII shows that no correlation was found between orthodontic techniques and rr (p > 0.05).

Association between prescriptions (Roth, MBT) and rr.

| Significance level | 0.44 | 0.68 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tooth | 15 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 |

| 45 | 44 | 43 | 42 | 41 | |

| Significance level | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.53 |

| Significance level | 0.42 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.38 |

| Tooth | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | |

| Significance level | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.55 | 0.39 |

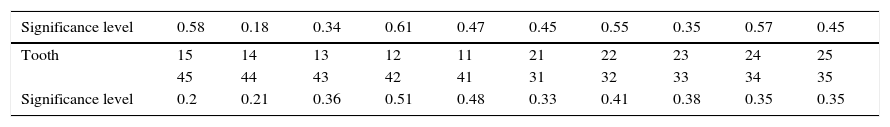

The variables gender and rr were cross-related for each tooth and like the previous cases, no association was found (p > 0.05) (Table VIII).

DISCUSSIONThe majority of the rr studies that have been conducted have documented rr only in upper incisors;16,38,39,40 or in upper and lower incisors;41,42 only a few have been performed in premolars and canines.13,43

in this study, more rr was found in incisors than in premolars, possibly due to an increased time or movement complexity required for the correction of the malocclusion; for example: the correction of anterior crowding requires more movements in the three planes of the space, which coincides with the studies conducted by De Freitas et al. (2013);43 as well as the research by Sameshima et al. (2001).13

Upon determining whether there was a relationship between an extraction or non-extraction treatment and rr, no significant difference was found, as in the studies of Kocadereli et al. (2011),6 Sameshima et al. (2001),13 Linge et al. (1991),18 Jiang et al. (2010),27 Nigul et al. (2006),38 Motokawa et al. (2012),39 De Freitas et al. (2013),43 Kaley et al. (1997);44 in addition to the one by Baumrind et al. (2006);45 where it is explainedthat the reason for this may be that the greater amount of space created when performing extractions is consumed as the crowding is resolved, therefore retraction is reduced in terms of millimeters to close and the roots are not so affected, as one might have imagined.

No relationship was found between gender and rr, as in the reports of Kocadereli et al.,6 Sameshima et al.,13 Linge et al.,18 Jiang et al.,27 Pandis et al.;34 and De Freitas et al.43

In regard to treatment time and rr, no relationship was found between these variables. This coincides with the studies of Kaley et al.,44 Baumrind et al.;45 and also with Zahed et al.46

Although no association was found between the employed orthodontic technique and rr, when analyzing the results, it was found that with MBT techniquethere was more rr compared to the Roth technique. This is probably due to the fact that MBT is a sliding mechanics technique where frictional resistance plays an important role and may therefore be related with rr. The abovementioned techniques had not been previously compared, however, in 1998 Parker et al. found no difference in rr between Edgewise, Begg and Roth.47 In a study published in 2013, Zahed et al. compared the MBT and Edgewise techniques, determining that MBT caused more rr.46

CONCLUSIONSAccording to this study's criteria:

- 1.

All teeth showed some degree of apical root resorption.

- 2.

The more susceptible teeth to rr were the upper and lower right incisors.

- 3.

There is no greater degree of rr in teeth subjected to orthodontic treatment with extractions in relation to teeth treated with a non-extraction approach.

- 4.

There is no gender predisposition for apical root resorption.

- 5.

There is a greater risk to develop rr in sliding mechanics orthodontic techniques possibly due to frictional resistance.

- 6.

The most commonly used extraction protocol was upper and lower first premolars.

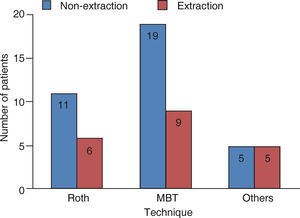

| LTISd1 | Upper right central incisor total pre-treatment length | LTISi 1 | Upper left central incisor total pre-treatment length |

| LTILSd1 | Upper right lateral incisor total pre-treatment length | LTILSi1 | Upper left lateral incisor total pre-treatment length |

| LTCSd1 | Upper right canine total pre-treatment length | LTCSi1 | Upper left canine total pre-treatment length |

| LT1PMSd1 | Upper right first premolar total pre-treatment length | LT1PMSi1 | Upper left first premolar total pre-treatment length |

| LT2PMSd1 | Upper right second premolar total pre-treatment length | LT2PMSi1 | Upper left second premolar total pre-treatment length |

| LTIId1 | Lower right central incisor total pre-treatment length | LTIIi1 | Lower left central incisor total pre-treatment length |

| LTILId1 | Lower right lateral incisor total pre-treatment length | LTILIi1 | Lower left lateral incisor total pre-treatment length |

| LTCId1 | Lower right canine total pre-treatment length | LTCIi1 | Lower left canine total pre-treatment length |

| LT1PMId1 | Lower right first premolar total pre-treatment length | LT1PMIi1 | Lower left first premolar total pre-treatment length |

| LT2PMId1 | Lower right second premolar total pre-treatment length | LT2PMIi1 | Lower left second premolar total pre-treatment length |

| LTISd2 | Upper right central incisor total post-treatment length | LTISi2 | Upper left central incisor total post-treatment length |

| LTILSd2 | Upper right lateral incisor total post-treatment length | LTILSi2 | Upper left lateral incisor total post-treatment length |

| LTCSd2 | Upper right canine total post-treatment length | LTCSi2 | Upper left canine total post-treatment length |

| LT1PMSd2 | Upper right first premolar total post-treatment length | LT1PMSi2 | Upper left first premolar total post-treatment length |

| LT2PMSd2 | Upper right second premolar total post-treatment length | LT2PMSi2 | Upper left second premolar total post-treatment length |

| LTIId2 | Lower right central incisor total post-treatment length | LTIIi2 | Lower left central incisor total post-treatment length |

| LTILId2 | Lower right lateral incisor total post-treatment length | LTILIi2 | Lower left lateral incisor total post-treatment length |

| LTCId2 | Lower right canine total post-treatment length | LTCIi2 | Lower left canine total post-treatment length |

| LT1PMId2 | Lower right first premolar total post-treatment length | LT1PMIi2 | Lower left first premolar total post-treatment length |

| LT2PMId2 | Lower right second premolar total post-treatment length | LT2PMIi2 | Lower left second premolar total post-treatment length |

This article can be read in its full version in the following page: http://www.medigraphic.com/ortodoncia

Student of the Orthodontics Specialty, Faculty of Dentistry (FO), National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).