Soft tissue facial profile is one of the most important elements for orthodontic diagnosis and treatment. It is influenced by genetic factors, heritage, race, ethnicity, environmental factors (mouth breathing, atypical swallowing habits) sagittal maxillo-mandibular position, facial biotype, type of muscles among others.

ObjectiveTo correlate facial profile with dimensions and shape of the dental arches in a school population of Yucatan.

Material and methodsAn observational, prospective, analytical, cross-sectional study of models and photographs from 6-8 year-old scholars enrolled as regular students in two schools of southern Yucatan.

ResultsThe study group consisted of 88 models and photographs: 52.27% were from male subjects and 47.72% from females. The predominant facial profile was convex for both genders. OrthoForm III arch shape was the most observed. The association between facial profile and upper and lower arch shape was determined by χ2 test, showing a statistically significant relationship (p < 0.05).

ConclusionsIt would be convenient to establish specific normal values for each geographic region, taking into consideration environmental, genetic and nutritional factors as well as race, ethnicity, gender and age.

El perfil facial de los tejidos blandos es uno de los elementos importantes para el diagnóstico y tratamiento ortodóntico; se encuentra influenciado por factores genéticos, hereditarios, raza, grupo étnico, ambiental (respirador bucal, hábitos deglución atípica), posición sagital maxilo-mandibular, biotipo facial, tipo de musculatura, entre otros.

ObjetivoCorrelacionar el perfil facial con las dimensiones y la forma de los arcos dentarios en escolares de una población de Yucatán.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional, prospectivo, analítico y transversal de modelos y fotografías de escolares de 6 a 8 años inscritos como alumnos regulares en dos escuelas del sur de Yucatán.

ResultadosEl universo de estudio estuvo conformado de 88 modelos y fotografías representando el 52.27% el sexo masculino y constituyendo el 47.72% el sexo femenino. El perfil que predominó fue el convexo para ambos sexos. La forma de arco OrthoForm III fue la que más se observó. La asociación entre el perfil facial y la forma del arco superior e inferior se determinó a través de la prueba de χ2, observándose una relación estadísticamente significativa (p < 0.05).

ConclusionesSería conveniente establecer normas específicas para cada región geográfica tomando en cuenta los factores ambientales, genéticos, alimenticios, raza, grupo étnico, sexo y edad.

Facial profile is determined in the sagittal plane and may be assessed as straight, concave or convex depending on the spatial relationship or harmony between mandible and maxilla.1,2

Soft tissue facial profile is an important asset to diagnosis and treatment planning in orthodontics. It is also substantial throughout treatment since it has the ability to make it conditional. Likewise, soft tissue profile is useful in interdisciplinary work with forensic sciences, plastic surgery and aesthetics, anthropology, maxillofacial surgery, genetics and psychology.3,4

Each facial profile has particular features regarding the dental arches:

- •

Straight profile: spatial relations of bony structures in harmony.

- •

Convex profile: may be associated with narrow arches and high palatal vault.

- •

Concave Profile: dental arch relatively wide and square-shaped.1

Swlerenga et al. (1994) conducted a comparative study in Mexican-American facial profiles and found large differences between groups thus concluding that Mexican-American population presents different results when compared to other groups.5

Shape and dimensions of the dental arches is influenced mainly by genetics, although there are inter-individual variations associated with gender, race, facial biotype, dental eruption, tooth movement after eruption, bone growth, environmental influences such as habits (digital sucking, mouth breathing, atypical swallowing, lip habit) and individual growth.6,7

Agurto P. and Sandoval P. (2011) conducted a study to determine the morphology of the maxillary and mandibular arch in Mapuche and non-Mapuche population. They were able to observe a greater proportion of oval-shaped maxillary and mandibular arches both in the Mapuche and in the non-Mapuche population.6

The aim of this study was to correlate facial profile with dental arch dimension and shape in schoolchildren from a population of Yucatan.

MATERIAL AND METHODSThe design of the present study was observational, analytical, prospective and cross-sectional. Study universe consisted of 88 models and photographs of school children 6 to 8 years of age with an average of 7.39 years. 46 of them were male thus representing 52.27% of the population and 42 were female scholars which accounted for 47.72%, of the study universe. All schoolchildren were enrolled and regular in schools of the municipalities of Catmís and Tzucacab, Yucatan.

Name and date of birth was registered for each patient. Facial profile photographs and study models were obtained in order to determine shape and dimensions of the dental arches. Facial profile was determined by the soft tissue profile angle suggested by Arnett and Bergman: the internal angle formed by drawing a line from the following points: Glabella (G; most point prominent of the forehead), Subnasal (Sn; most posterior point of the nasal columnella) and soft tissue Pogonion (Pg’: most prominent point of the chin) was measured. Study models were classifi ed according to 3M Unitek® (OrthoForm Templates Diagnostics Set) arch shape templates which consider OrthoForm I as a triangular-shaped arch, OrthoForm II as a square-shaped one and OrthoForm III as oval.

Dimensions of the dental arches (intermolar distance, intercanine distance, palatal length and depth) were determined with the aid of 3D Mestro Ortho Studio® software.

Normality tests were conducted in order to determine the statistical test according to the values; correlation analysis was determined using the Spearman coefficient test for intermolar distance and palatal length. Pearson correlation was used for intercanine distance and palatal depth and Pearson's χ2 test, for arch form. The confidence interval was set at p = 95%.

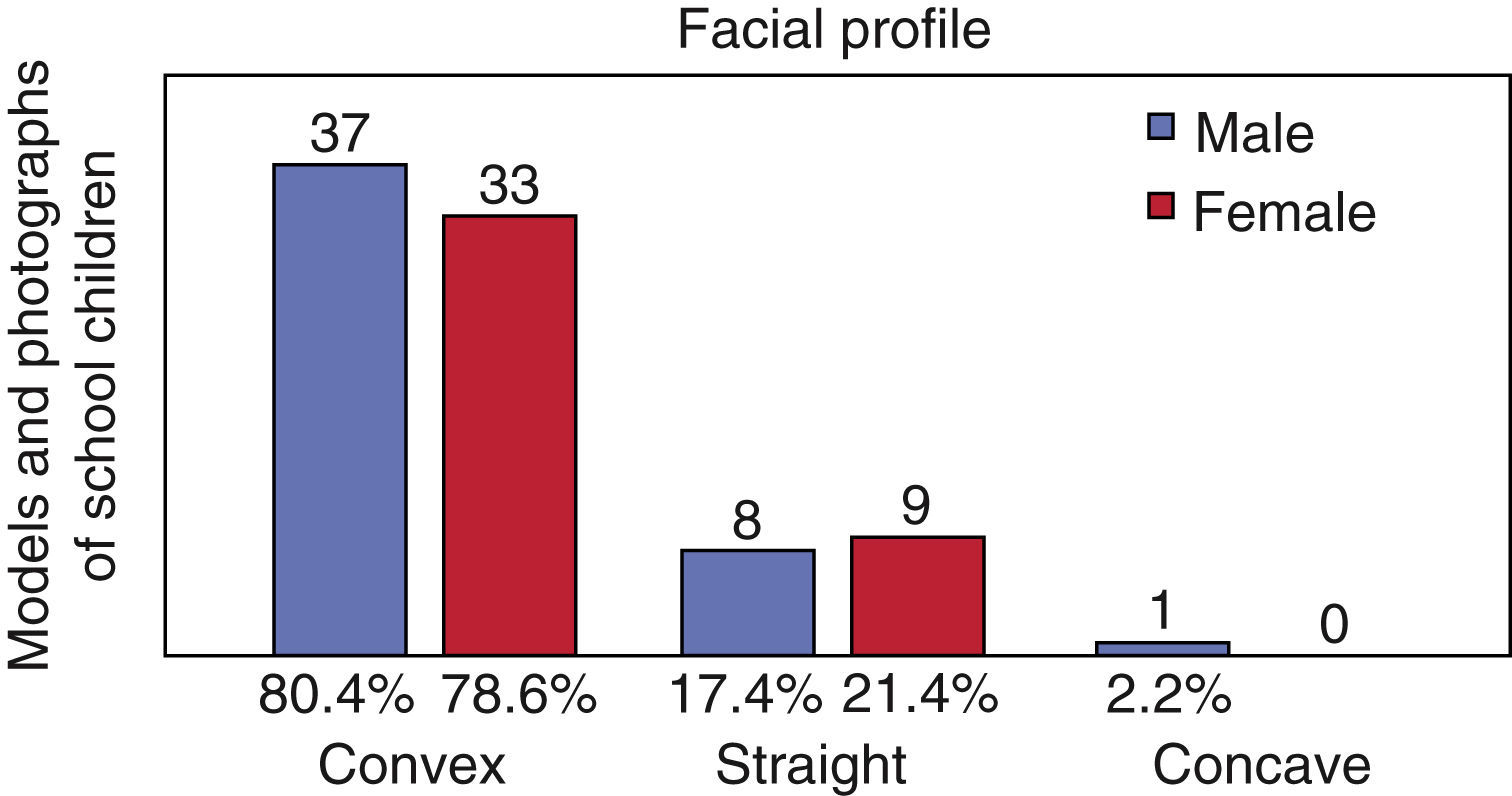

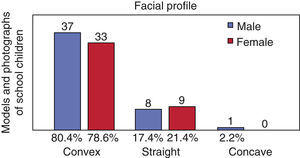

RESULTSRegarding facial profile, in males, the convex type was observed in 37 individuals (80.4%); the straight, in 8 (17.4%) and the concave in 1 (2.2%). In females a convex profile was observed in 33 individuals (78.6%), a straight one in 9 (21.4%) no concave profile was observed (Figure 1).

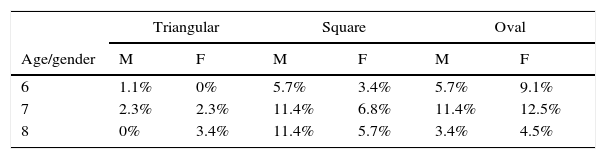

The most common shape of the upper dental arches at age 6 and 7 in males was oval and square equally (5.7% at 6 years and 11.4 at 7 years of age); in the female gender, the oval shape at 6 years (9.1%) and 7 years (12.5%) of age prevailed and at 8 years the square form was the most prevalent for both genders (11.4% males and 5.7% females) (Table I).

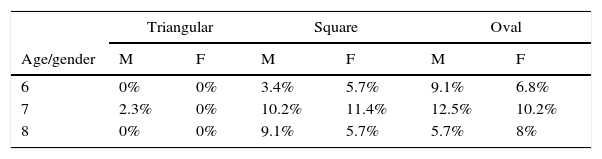

Regarding lower arch form and age, the highest prevalence at 6 years of age was the oval shape; 9.1% in males and 6.8% in females; at 7 years of age, the oval shape was most prevalent in men (12.5%) and the squared shape in women (11.4%). At the age of 8, the most prevalent arch form is the squared with 9.1% in men and 8% in women the oval shape (Table II).

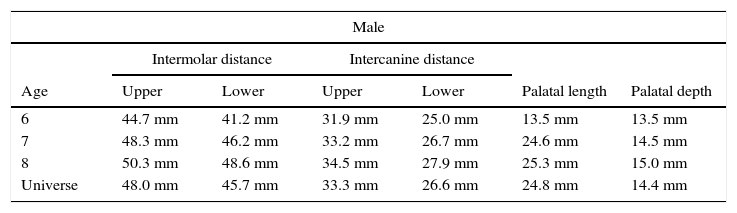

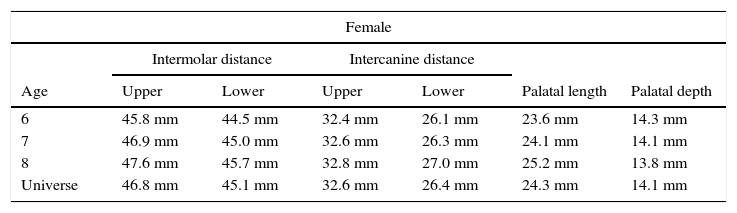

In the dental arch dimensions and intermolar distance mean values (intercanine distance palatal length and depth) an increase by age may be observed for both genders, with the exception of palatal depth which decreases 0.3mm in 8-year-old females (Tables III and IV).

Upper dental arch mean values.

| Male | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermolar distance | Intercanine distance | |||||

| Age | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Palatal length | Palatal depth |

| 6 | 44.7 mm | 41.2 mm | 31.9 mm | 25.0 mm | 13.5 mm | 13.5 mm |

| 7 | 48.3 mm | 46.2 mm | 33.2 mm | 26.7 mm | 24.6 mm | 14.5 mm |

| 8 | 50.3 mm | 48.6 mm | 34.5 mm | 27.9 mm | 25.3 mm | 15.0 mm |

| Universe | 48.0 mm | 45.7 mm | 33.3 mm | 26.6 mm | 24.8 mm | 14.4 mm |

Lower dental arch mean values.

| Female | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermolar distance | Intercanine distance | |||||

| Age | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Palatal length | Palatal depth |

| 6 | 45.8 mm | 44.5 mm | 32.4 mm | 26.1 mm | 23.6 mm | 14.3 mm |

| 7 | 46.9 mm | 45.0 mm | 32.6 mm | 26.3 mm | 24.1 mm | 14.1 mm |

| 8 | 47.6 mm | 45.7 mm | 32.8 mm | 27.0 mm | 25.2 mm | 13.8 mm |

| Universe | 46.8 mm | 45.1 mm | 32.6 mm | 26.4 mm | 24.3 mm | 14.1 mm |

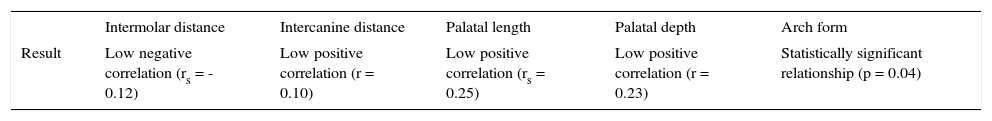

The Spearman's Rho was obtained to determine the association between facial profile and upper and lower intermolar distance, obtaining a low negative correlation (rs = -0.12) but with no statistical significance.

To determine the association between facial profile and upper and lower intercanine distance, the Pearson's correlation coefficient was obtained, which showed a low positive correlation (r = 0.10), but with no statistical significance.

To determine the association between facial profile and palatal length, the Spearman's Rho was obtained which showed a low positive correlation, although without statistical significance.

A low non-significant positive correlation was observed between facial profile and palatal depth.

The association between facial profile and shape of the upper and lower arch was determined through the χ2 test which demonstrated a statistically significant correlation (p < 0.05) (Table V).

Correlation.

| Intermolar distance | Intercanine distance | Palatal length | Palatal depth | Arch form | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Low negative correlation (rs = -0.12) | Low positive correlation (r = 0.10) | Low positive correlation (rs = 0.25) | Low positive correlation (r = 0.23) | Statistically significant relationship (p = 0.04) |

The convex facial profile was predominant in our study which coincides with the results from Swlerenga et al. (1994), who in a comparative study between Mexican-American subjects, white Americans and black Americans, found that the convex facial profile prevailed in Mexican-American subjects and in white Americans, a straight profile prevailed, demonstrating once again that there are no universal standards for determining facial profile.5

In this investigation it was observed that oval shape (OrthoForm III) was the one that prevailed (46.6%) in the upper dental arch and in the lower dental arch (52.3%). These results coincide with those of Agurto P. and Sandoval P. who compared two groups: Mapuche and non-Mapuche in Chile, in 75 children between 10 and 14 years of age and determined that OrthoForm III shape as predominant in both study groups.6 Rivera et al also studied shape and size of the dental arches in an Amazonian indigenous population between the ages of 6 and 12 years and found that 86% of the population had oval-shaped maxillary arches and the remaining 14%, a square arch form in the maxilla. In the mandibular arch, 75% was oval and 25% squared; no data was found for the triangular shape.8

On the other hand, Kook et al. in a study to determine dental arch form between two populations, one Korean and the other white American, observed a square shape in 46.7% of the cases followed by the oval shape with 34.5% and the triangular one with 18.8% in Koreans. The white American group presented more frequently the triangular shape with 43.8%, followed by the oval with 38.1% and the square with 18.1%, thus suggesting a difference between the groups,9 unlike what was found in this investigation where the predominant arch form was oval.

Dental arch dimensions and palatal length increased according to age, approximately 0.5mm per year. This finding coincides with what was reported by Cassidy et al. in a study of 320 subjects between 10 and 19 years of age,10 Rastegar-Lair et al. in a population from Kuwait between 13 to 14 years,11 and Lara-Carrillo et al. in 12 to 17 year-old Mexicans.12

However, Rivera and cols. in a population of Amazonian indigenous peoples between 6 and 12 years of age found no variation in dental arch dimensions which remained stable; attributing this fact to age range.8

CONCLUSIONSIn a population of southeastern Yucatan the most predominant profile was the convex profile for both genders. In a general way dimensions of the dental arches increased in males and remained stable in females. The results may have great clinical importance in the making of good diagnosis and adequate orthodontic treatments in our patients since dental arch form cannot be general. Dental arch form must be determined and identified in order not to modify its shape substantially.

To the administrative and academic authorities of the Faculty of Odontology of the UADY for the facilities provided for conducting this research.

Department of Orthodontics and Dentomaxillofacial Orthopedics. Faculty of Odontology.

This article can be read in its full version in the following page: http://www.medigraphic.com/ortodoncia