The present study was conducted in order to propose two angles for the assessment of the anteroposterior position of the upper and lower lips, taking as a reference stable bone structures thus avoiding soft tissue reference points that vary according to age such as the nose and chin.

Material and methods114 lateral headfilms from skeletal class I, II and III patients were traced. The proposed angles were measured. For the upper lip (LSMx), the palatal plane and the anterior nasal spine-upper stomion plane formed the angle. For the lower lip (LIMd) the angle was formed by the mandibular plane and the pogonion-lower stomion plane. Both angles were compared with the nasolabial (NSL) and the mentolabial angles (MTL) respectively.

ResultsA statistical t-Student test was conducted. The proposed angles for the upper and lower lip had lower standard deviations from the mean in comparison to similar angles in all three classes, especially skeletal class I: LSMx: 105.5° ± 5.5, LIMd: 88° ± 5.5, NSL: 104.1° ± 11.3 and MTL: 136.9° ± 12.4. The angle proposed for the lower lip showed a smaller standard deviation and a statistically significant difference compared to the mentolabial angle in the ANOVA test (p ¿ 0.05).

ConclusionsThe proposed angles for assessing lip position indicate that they have smaller deviations from the mean, in addition if there is an increase they show lip protrusion and a decrease indicates lip retrusion.

El presente estudio se realizó para proponer dos ángulos para evaluar la posición anteroposterior de los labios superior e inferior, tomando como referencia de apoyo estructuras óseas estables, evitando así tener un apoyo de tejido blando que varía de acuerdo con la edad como es la nariz y el mentón.

Material y métodosSe trazaron 114 radiografías laterales de pacientes clase I, II y III esqueletal. Se midieron los ángulos propuestos para el labio superior (LSMx) que se formaban por plano palatino y el plano espina nasal anterior-estomión superior. Para el labio inferior (LIMd) fue el ángulo formado por el plano mandibular y el plano pogonión-estomión inferior, a ambos se les comparó con los ángulos nasolabial (NSL) y mentolabial (MTL), respectivamente.

ResultadosA tales medidas se realizó una prueba estadística de t-Student. Los ángulos propuestos para labio superior e inferior obtuvieron menores desviaciones estándar de la media a comparación de sus ángulos semejantes en las tres clases esqueletales, sobre todo para clase I esqueletal: LSMx: 105.5° ± 5.5, LIMd: 88° ± 5.5, NSL: 104.1° ± 11.3 y MTL: 136.9° ± 12.4. El ángulo propuesto para el labio inferior tuvo menor desviación estándar y una diferencia estadísticamente significativa frente al ángulo mentolabial en la prueba de ANOVA (p ¿ 0.05).

ConclusionesLos ángulos propuestos para evaluar la posición de los labios indican tener menores desviaciones de la media, además, si presentan un aumento indican protrusión labial y una disminución es retrusión labial.

It is important to assess the position of the lips in the patient who seeks orthodontic treatment. The aesthetic appreciation of the lips will vary for each observer, but the indications, contours and proportions approximate to a mean or facial aesthetic standards indicate a more esthetic and harmonious facial appearance as indicated by Bergman et al.1 The lips according to their development have a position in the face according to their thickness, size and length. These can be assessed by different means already proposed by several authors such as Ricketts’ E line,2 S1 line of Steiner,3 B line of Burstone,4 Sushner's S2 line5 and the Holdaway H line.6 These lines were evaluated by Buschang et al and they found that the profile planes only determine if the lip position is adequate to the face,7 but if these same planes were used to evaluate significant changes after orthodontic treatment or growth they would not allow a significant quantification of the changes in lip position.

There are other ways to asses lip position such as the true vertical,8 the mentolabial and nasolabial angles9 and a more accurate way through projections to the pterigomaxillary vertical line, exposed by Nanda et al.10 But regarding the abovementioned references most studies have been performed in adolescents up to the age of 18, without considering that lips vary with age. Studies by Pecora et al.,11 Genecov et al.,12 Nanda et al.,10 Foley et al.13 and Bergman et al1 have shown significant changes that happen in the maturation of lips, nose and chin, as well as a significant variation in the mentolabial and nasolabial angles.

Soft tissues are constantly changing, more than the facial skeleton and into adulthood there is an increase in length and a decrease in lip thickness.14 However Bishara et al indicated that there is soft tissue stability at 25 years of age, and from the age of 30 years the chin and nose move further down and forwards.15

Therefore the question was raised as to whether it is possible to develop new angles to assess the position of the upper and lower lip with respect to a stable bony point, without the intervention of a secondary soft tissue reference point that may suffer changes through the course of life. These proposed angles should have less variability or standard deviation from the norm unlike the commonly use dangles: the nasolabial and mentolabial angles, which were included in the study in order to make a comparison.

MATERIAL AND METHODSThis analysis was conducted by means of a transverse observational study, which consisted in hand tracing and measuring lateral head films obtained from the archive of the Orthodontics Specialty of the Division of Post-Graduate Studies and Research at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The inclusion criteria for this study were: lateral head films taken in the Radiology Department of the same institution and recorded on a compact disc using with Cliendent Software during the period from November 2013 to February 2015, then printed on coated paper in a 1:1 proportion; lips at rest position; patients between the ages of 18 to 30 years; patients diagnosed as skeletal class I, II and III through the following cephalometric measurements: Jarabak's ANB, Wits of Jacobson, facial convexity of Downs and convexity of Ricketts. Exclusion criteria were: patients who have had extractions of teeth with the exception of the third molars; patients who had undergone previous orthodontic treatment and that at least one skeletal measurement did not match.

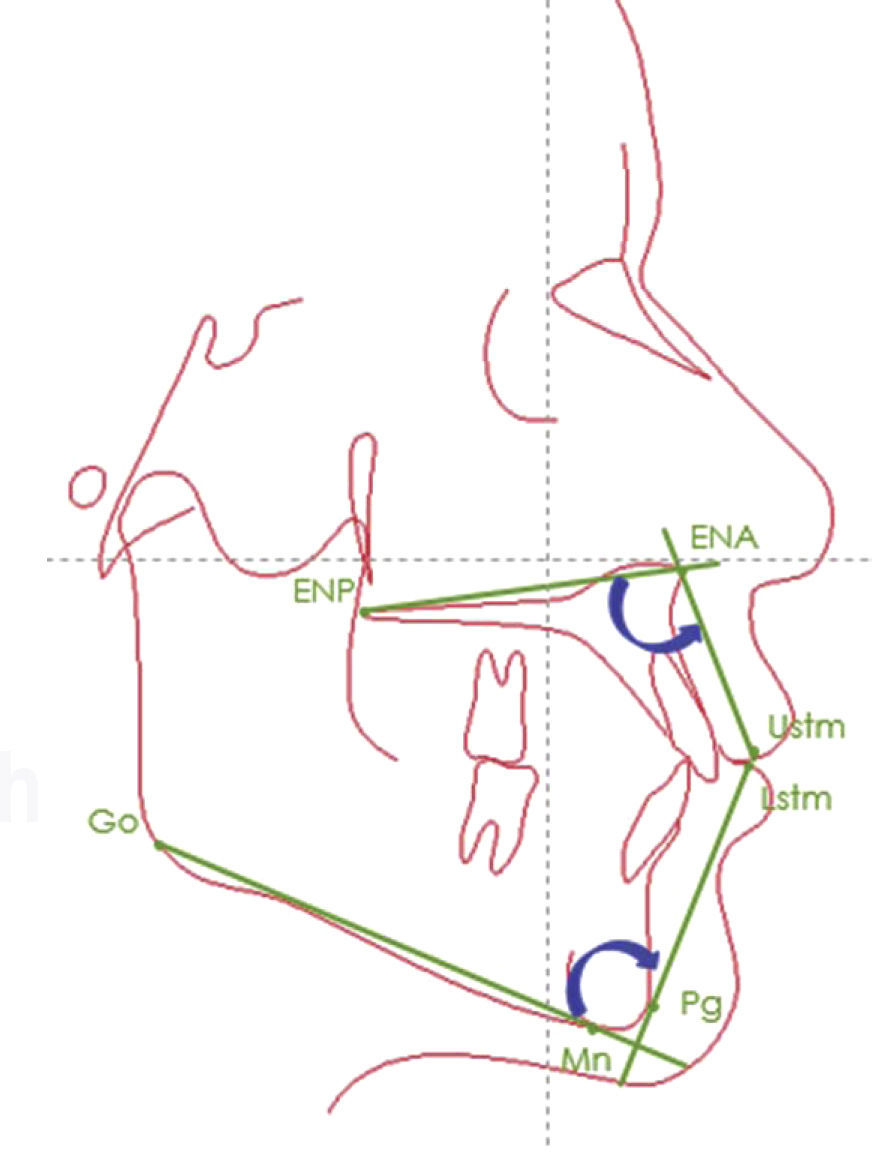

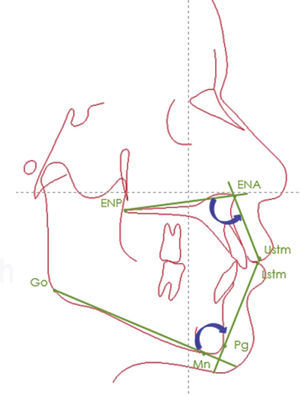

The angles proposed to evaluate the anteroposterior position of the upper and lower lips were: for the upper lip (LSMx), it would be through the lower inner corner formed by the palatal plane (ANS-PNS) and the plane formed by the points from the anterior nasal spine to estomion of upper lip (Ustm). This proposed angle was compared to the nasolabial angle (NSL). For the lower lip (LIMd) the proposal was to measure the internal top angle formed by the mandibular plane and the plane that goes from bone pogonion point to estomion point of the lower lip (Lstm), so this was compared with the mentolabial angle as well (Figure 1).

A pilot test was conducted in which out of 55 lateral head films, 15 were within the parameters of the inclusion criteria regarding the skeletal class I and in addition, the mentolabial and nasolabial angles were within their standard (7 men and 8 women). An intraobserver calibration test was performed: the same radiographs were traced two weeks later and then an interobserver calibration was performed by the co-author of this study. There were no differences in terms of the cephalometric references radiographs taken in the study.

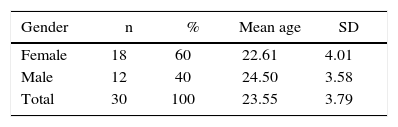

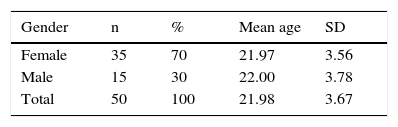

RESULTS114 lateral head films were evaluated. The mean age was 22.2 (± 3.5) years; 68.425 of the subjects were women and 31.58, men. For each skeletal class a Student's t-test for mean and standard deviation analysis was performed and thus groups were compared. Additionally the ANOVA test for statistical differences was performed (p ¿ 0.05).

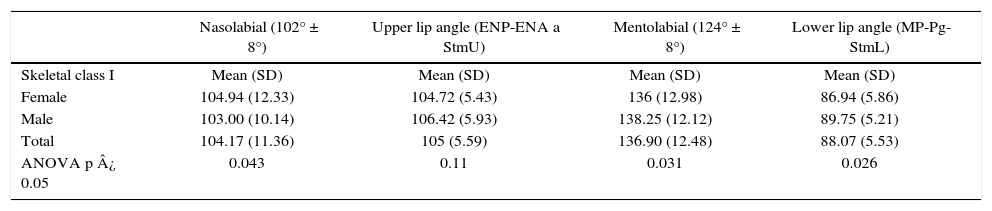

In skeletal class I there were 30 X-rays of patients with an average age of 23.5 years. The proposed angle for the upper lip had a mean of 105° ± 5.5°, compared to the nasolabial angle which had a mean of 104.1° ± 11°. In the angle proposed for the lower lip the mean was 88° ± 5.5° and the mentolabial angle was 136.9° ± 12.4° by which it can be seen that there is a smaller standard deviation of the mean in the angles proposed for each lip. The LIM dangle had a statistically significant difference compared to the mentolabial angle (Tables I and II).

Nasolabial, upper lip, mentolabial and lower lip angles according to gender in skeletal class I patients.

| Nasolabial (102° ± 8°) | Upper lip angle (ENP-ENA a StmU) | Mentolabial (124° ± 8°) | Lower lip angle (MP-Pg-StmL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal class I | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Female | 104.94 (12.33) | 104.72 (5.43) | 136 (12.98) | 86.94 (5.86) |

| Male | 103.00 (10.14) | 106.42 (5.93) | 138.25 (12.12) | 89.75 (5.21) |

| Total | 104.17 (11.36) | 105 (5.59) | 136.90 (12.48) | 88.07 (5.53) |

| ANOVA p ¿ 0.05 | 0.043 | 0.11 | 0.031 | 0.026 |

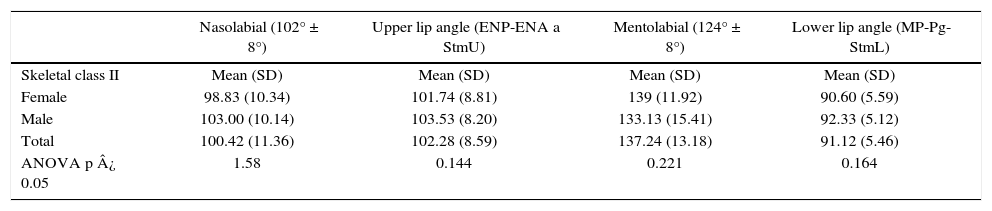

For skeletal class II patients, 50 lateral head films were obtained with a mean age of 21.9 ± 3.6 years. For the upper lip angle, the mean was 102.2° ± 8°; for the nasolabial, 100.4° ± 11°; the proposed angle for the lower lip was 91.1° ± 5.4° while the mentolabial was 137.2° ± 13.1°. Thus it is maintained that the proposed angles have a lower standard deviation from their norm, but only the LIMd angle continues to have a lower statistical difference compared to the others (Tables III and IV).

Nasolabial, upper lip, mentolabial and lower lip angles according to gender in skeletal class II patients.

| Nasolabial (102° ± 8°) | Upper lip angle (ENP-ENA a StmU) | Mentolabial (124° ± 8°) | Lower lip angle (MP-Pg-StmL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal class II | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Female | 98.83 (10.34) | 101.74 (8.81) | 139 (11.92) | 90.60 (5.59) |

| Male | 103.00 (10.14) | 103.53 (8.20) | 133.13 (15.41) | 92.33 (5.12) |

| Total | 100.42 (11.36) | 102.28 (8.59) | 137.24 (13.18) | 91.12 (5.46) |

| ANOVA p ¿ 0.05 | 1.58 | 0.144 | 0.221 | 0.164 |

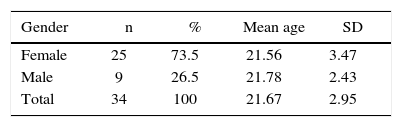

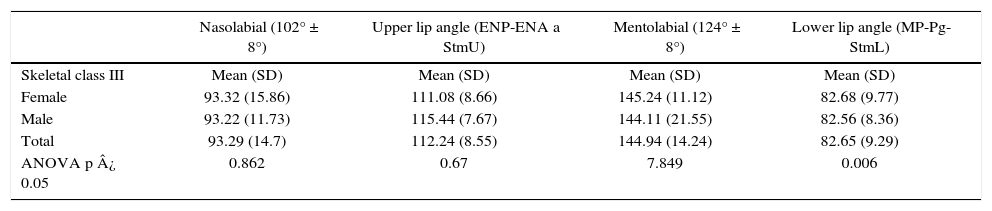

In the group for skeletal class III, there were 34 X-rays of patients with a mean age of 21.6° ± 2.9° years. The result of the angles were: for the upper lip angle, 112.2° ± 8.5°; nasolabial angle, 93.2° ± 14.7°; for the lower lip, 82.6° ± 9.2° and for the mentolabial, 144.9° ± 14.2°. The results in this group for the proposed angles despite having greater diversion from their means, remain lower than the mentolabial and nasolabial angle. The angle proposed for the lower lip is the one that remained with a statistically significant difference compared to the other angles in this group (Tables V and VI).

Nasolabial, upper lip, mentolabial and lower lip angles according to gender in skeletal class III patients.

| Nasolabial (102° ± 8°) | Upper lip angle (ENP-ENA a StmU) | Mentolabial (124° ± 8°) | Lower lip angle (MP-Pg-StmL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal class III | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Female | 93.32 (15.86) | 111.08 (8.66) | 145.24 (11.12) | 82.68 (9.77) |

| Male | 93.22 (11.73) | 115.44 (7.67) | 144.11 (21.55) | 82.56 (8.36) |

| Total | 93.29 (14.7) | 112.24 (8.55) | 144.94 (14.24) | 82.65 (9.29) |

| ANOVA p ¿ 0.05 | 0.862 | 0.67 | 7.849 | 0.006 |

The proposed angles to measure the anteroposterior position of the upper and lower lips considered more stable cephalometric bone points, without relying on soft tissue points such as those in the nose, chin or others that have considerable changes during the course of life.

Regarding the proposed upper lip angle, the palatal plane was used. This coincides with what was suggested by Brodie et al.: that it is the most stable plane in the facial skeleton since it has fewer changes during growth. He also noted that the anterior nasal spine and pogonion carry a descent and clockwise rotation with time and not in an anteroposterior direction, which also supports the choice of the pogonion point for the lower lip angle.16 In addition as Björk Arne (1963) indicated, the anterior edge of the chin remains more stable during growth.17,18

According to Jacob and Buschang (2014) in the mandibular plane there are no significant changes from the age of 17 years and a stabilization of the mandibular growth takes place around the 18 years of age.19 Besides, in adults the maxilla and the mandible have more vertical than anteroposterior changes, which favors our bony points and planes in being the support to measure the anteroposterior position of the lips.14

In terms of soft tissue points selected on the lips, Graber et al. indicate that the upper and lower stomion only suffer changes in a vertical direction.20 Additionally, Bishara et al described (1998) the changes in the lips from 25 years of age: the upper lip begins to lengthen and the lower starts going down. So these proposed angles favor having a smaller discrepancy from their mean to assess their anteroposterior position.15

With regard to the results, the sample consisted of Latin-Mexican patients. In the group of skeletal class I the nasolabial angle was 104° ± 9.5° and the mentolabial, 136.0° ± 12.5°. Therefore, these values can serve as reference for this population. Similar studies such as the one by Fitzgerald et al, which evaluated the reproducibility of the nasolabial angle in U.S. population and obtained an average of 114° ± 10° which indicated that the variability of this angle is due to the inclination of the columnella and upper labralle.21 Other studies have measured the nasolabial angle: Kohila et al. in an Hindu population and its value was 116° ± 10°; Scavone et al in Brazilians with 108° ± 11°; Loi et al. (2005) in Japanese: nasolabial 96.8° ± 10° and mentolabial is 135° ± 13°; and in the study of McNamara et al the nasolabial angle was 102° ± 8° and the mentolabial, 124° ± 8°. All of the abovementioned studies indicate that the mentolabial and nasolabial angles have a wide diversion from their averages. On the contrary our proposal to measure the upper and lower lip got little deviation from the average in the three skeletal classes, especially in the skeletal class I group. Both angles had deviations of only five degrees from their mean.22–25

This study allows us to perform comparative measurements in patients in who lip position is going to be modified such as extraction or surgical treatments and thus have a better use of the angles that have been proposed.

CONCLUSIONS- •

The proposed angles to assess lip position indicate that there are minor deviations from the mean in Skeletal class I patients.

- •

Bony points meet the requirements of being more stable for creating planes or angles to evaluate lip position.

- •

The norm of the proposed angle for the upper lip is: 105° ± 5°, and for the lower lip: 88° ± 5°. An increase indicates lip protrusion and a decrease, lip retrusion.

This article can be read in its full version in the following page: http://www.medigraphic.com/ortodoncia