Retained teeth are defined as non-erupted, well-formed, teeth that remain inside the jawbone. Third molars as well as upper canines are the most frequently retained teeth, athough lower second premolars and supernumerary teeth are also prone to suffer retention.

ObjectivesTo replace retained canines with first maxillary premolars by using the labial cuspid of the first maxillary premolars as canine guidance and class I molar relationship coupled to a suitable anterior guidance.

Case reportA 16 year-old male patient with bilateral molar class III, primary maxillary canines and upper and lower anterior crowding: the radiographs show two supernumerary teeth between the lateral incisors and the first upper premolars and the impaction of the permanent maxillary canines over the upper central incisors roots, with resorption of a third of the upper right central incisor root and of the apical third of the lateral incisor in the same side, as well as the central and lateral in the opposite side.

ConclusionsThe replacement of the canines by premolars, excluding the orthodontic surgery, is a viable treatment with good functional, periodontal and esthetic results, as long as there is a good orthodontic management of the final position of the anterior teeth. Nevertheless, it's not a choice for all cases.

Se conoce como dientes retenidos aquéllos que se han formado dentro del hueso pero que han fracasado en su proceso de erupción. Los dientes que presentan retenciones con más frecuencia son los terceros molares de ambas arcadas y los caninos superiores, seguidos por los segundos premolares inferiores y los dientes supernumerarios.

ObjetivosSustituir los caninos retenidos por los primeros premolares maxilares, obteniendo la guía canina con la cúspide vestibular de los primeros premolares maxilares y la relación molar clase I con una guía anterior adecuada.

Reporte del casoPaciente de sexo masculino de 16 años de edad. Presenta clase III molar bilateral, caninos primarios maxilares y apiñamiento anterior superior e inferior; radiográficamente, se observan dos dientes supernumerarios entre los incisivos laterales y primeros premolares superiores, y la impactación de los caninos maxilares permanentes sobre las raíces de los incisivos centrales superiores con reabsorción de un tercio de la raíz del incisivo central superior derecho y del tercio apical del incisivo lateral del mismo lado, así como del central y lateral del lado opuesto.

ConclusionesLa sustitución de caninos por premolares eliminando la fase quirúrgica- ortodóncica, es un tratamiento viable con buenos resultados funcionales, periodontales y estéticos siempre y cuando se tenga un adecuado manejo ortodóncico en la posición final de los dientes anteriores, sin embargo no es una alternativa utilizable en todos los casos.

Retained teeth are known as those that have formed within the bone but have failed in the process of eruption. The teeth with greater frequency of dental retention are maxillary and mandibular third molars, followed by the maxillary permanent canines with a prevalence of almost 20 times greater than the mandible. This high incidence in deviations and retentions is due to the fact that the permanent canine presents space problems in the dental arch since it is one of the last teeth to erupt, has the largest development time (11 to 13 years in the upper arch and 10 to 11 years in the lower) and a long eruption path. Due to this factors, having reached their full development, they frequently remain trapped within the maxilla maintaining the integrity of the periocoronary sac.1–9

The most studied multidisciplinary problems in dentistry are the impaction of maxillary canines, however there is no strong etiological assumption. The most viable evidence is that of an isolated phenomenon or a polygenic multifactorial inheritance.10

Prevalence of the retained canines is 0.2-2.8%, and in most cases they present in an ectopic location. In a study by Ericson and Kurol in the year 2000, of 156 canines in ectopic location, it was found that in relation to the adjacent incisor roots, the crown of 21 per cent of the canines were in a buccal position;18% were distobuccal; 27%, palatal; 23%,distopalatal; 5 per cent, apical and only 4 per cent in an apical position relative to the lateral incisor; 1% of them were in an apical position in relation to the central incisor and 6 per cent in apical position between the central and lateral incisors. Many authors have reported that there is a greater prevalence of retained canines in women than in men, two to three times, the prevalence reported by Ericson and Kurol is of 1.17% in women and 0.51% in men.2,9–13

Several factors that contribute to canine retention have been mentioned in addition to the lack of space due to insufficient development of the jaw. These are: alterations in the eruption path, agenesis of the lateral incisor, genetic factors, ectopic location of the dental germ and the distance that it has to travel in order to erupt; bone tissue density, malposition of the adjacent teeth, extended retention of the deciduous tooth, presence of cysts, odontomas or supernumerary teeth, among others,3,4,9,14 other factors include: discrepancy between dental size and arc length, presence of an alveolar fissure, anchylosis, root dilaceration, iatrogeny, trauma, or idiopathic causes.

Among the risks associated with the presence of retained canines is root resorption of the adjacent teeth. Up to 50% of the maxillary canines cause ectopic resorptions in neighboring teeth. Commonly, the resorption appears in the middle and apical third of the root of the adjacent incisors, being the maxillary lateral incisors the most affected with a percentage of 38% and the central incisors with a 9%. Anchylosis of the impacted tooth may also occur, as well as its partial or total root resorption.2,9,11,15

MATERIALS AND METHODSCase report16-year-old male patient attends the Orthodontics Clinic of the University of Queretaro with a reason for consultation: «I want to straighten my teeth».

Clinical examinationThe facial analysis shows a brachifacial patient with a straight profile. At the intraoral clinical exploration, he presents a bilateral molar class III, maxillary primary canines, square-shaped upper and lower arch, upper and lower anterior crowding, dentoalveolar protrusion and proclination of upper and lower incisors and an overjet of 1.5mm and overbite of 1mm (Figures 1 and 2).

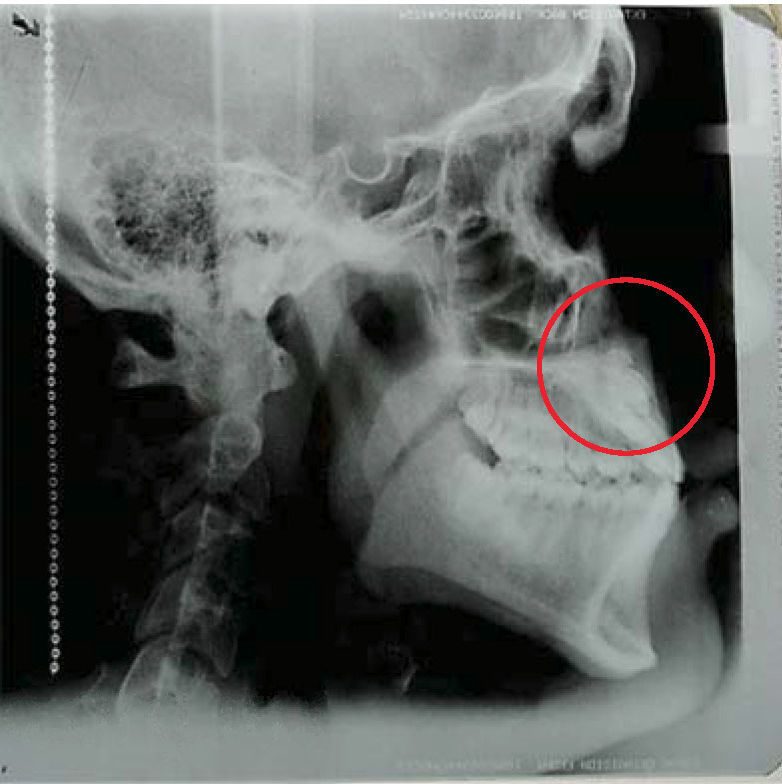

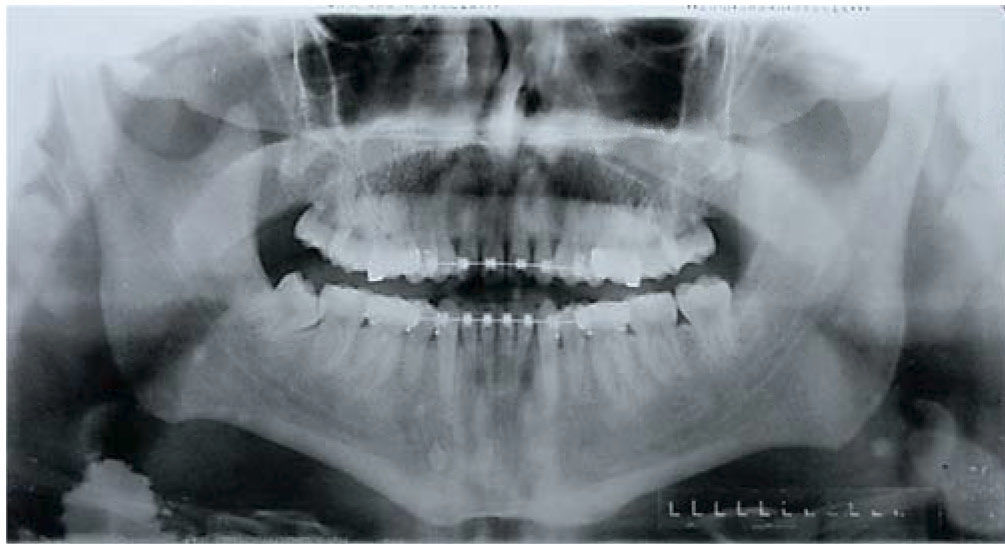

Radiographical examinationIn the panoramic radiograph two supernumerary teeth were observed between the lateral incisors and first premolars. The maxillary permanent canines were impacted over the roots of the upper central incisors. It was noted the resorption of one third of the root of the upper right central incisor and the apical thirds of the lateral incisor on the same side and of the central and lateral incisors of the opposite side. In the lateral headfilm the labial retention of the permanent canines was observed (Figures 3 and 4).

Cephalometric analysis showed a biprotrusive skeletal class II, horizontal growth, brachifacial biotype and uppern and lower dental protrusion and proclination (Figures 5 and 7).

Diagnosis- •

Male patient of 16 years of age.

- •

Biprotrusive skeletal class II.

- •

Straight profile with increased lower third.

- •

Horizontal growth.

- •

Bilateral class III molar relationship.

- •

Presence of deciduous upper canines.

- •

Presence of supernumerary teeth between lateral incisors and first premolars on both sides.

- •

Bilateral impaction of permanent upper canines.

- •

1mm overbite and 1.5mm overjet.

- •

Upper and lower proclination and dentoalveolar protrusion.

- •

Upper and lower crowding.

- •

Replace retained canines with first premolars.

- •

Achieve canine guidance with the buccal cusp of the first premolars.

- •

Achieve class I molar relationship.

- •

Obtain anterior guidance.

- •

Maintain the facial profile.

- •

Removal of the maxillary canines and replace them with the first premolars because these had the necessary size and root shape to achieve lingual crown torque.

- •

Substitute canine guidance with premolar guidance or group function.

- •

Placement of 0.022” x 0.025” slot Roth fixed appliances.

- •

Final articulation mounting in order to perform the occlusal adjustment and for the premolars to better withstand the occlusal loads.

- •

Rehabilitation with interproximal resins in the lateral incisors and premolars to achieve an adequate periodontal health.

The patient was referred for the removal of the deciduous canine and the first lower premolars and afterwards, to the Oral Surgery Clinic for the surgical removal of the supernumerary teeth and the retained permanent canines.

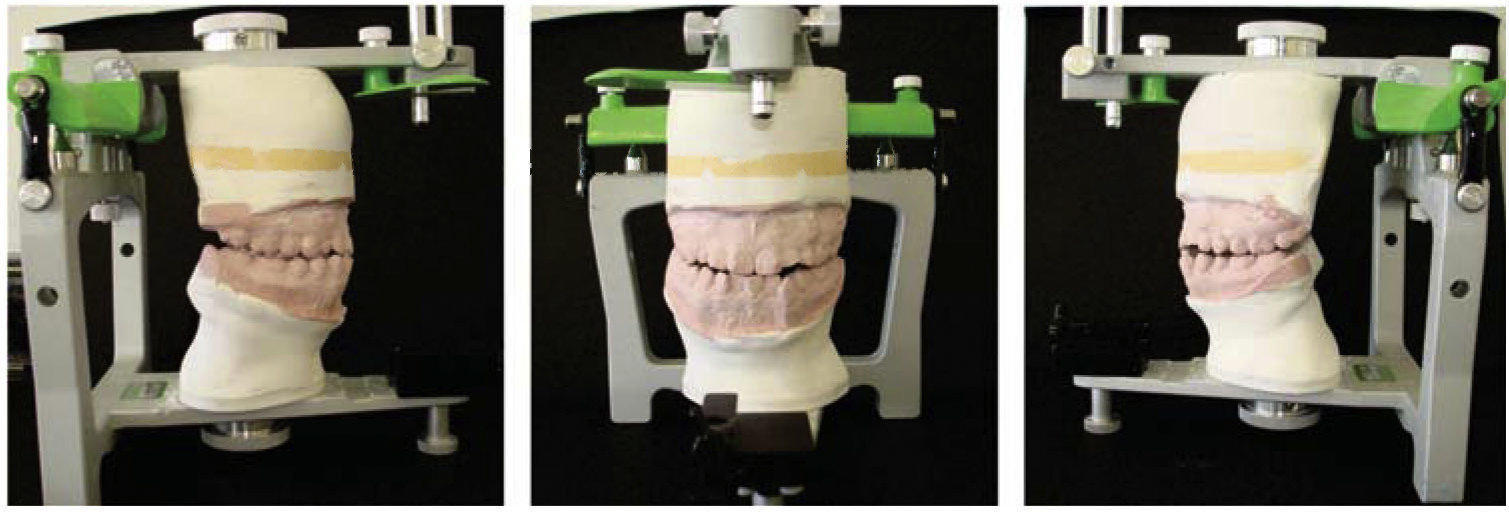

Articulator mounting was performed with the AD2 articulator to assess the discrepancy between CO and CR, which was within the acceptable standard in the sagittal, vertical and transverse relationship (Figure 8).

So it was proceeded to place 0.022” × 0.025” slot Roth appliances and begin the alignment with the following sequence of Nickel-Titanium thermal arch wires: 0.014”, 0.016”, 0.018”, 0.016” × 0.022” Super Elastic for 5 to 6 weeks each arch wire. The leveling stage was performed with rectangular 0.019” × 0.025” Nickel-Titanium thermal arch wires (Figure 9). Subsequently a 0.019” × 0.025” SS was placed before designing the closure arch wires.

Space closure was achieved with 0.019” × 0.025” TMA arch wires with T loop bends in the upper arch and a vertical loop with helix in the lower arches (Figure 10). After the spaces were closed the case was re-leveled with a 0.018” × 0.025” Nickel-Titanium thermal arch wires and a control panoramic radiograph was obtained for assessing root parallelism (Figure 11).

Brackets were re-positioned from lower canine to canine and a 0.016” Nickel-Titanium thermal arch wirewas placed, continuing with a 0.016” × 0.025” Super Elastic and afterwards, with a 0.017” × 0.025” stainless steel arch wire. The remaining spaces in the upper arch were closed with Nickel-Titanium springs over a 0.019” × 0.025” stainless steel arch wire (Figure 12).

Prior to the finishing stage, models were obtained and mounted on an articulator to perform an occlusal adjustment and improve the occlusal loads during masticatory function (Figure 13). Finishing and detailing was performed with 0.018” × 0.025” braided arch wires. Finally interproximal resins were placed in the lateral incisors and premolars to compensate for the dental discrepancy (Figure 14).

RESULTSWith this alternative treatment it was managed to establish a class I molar relationship on both sides, the dental midline was centered and anterior guidance was achieved by establishing an ideal overbite and overjet. Group function was achieved with the premolars replacing the impacted canines. A good periodontal health was obtained and the profile was improved as well as the patient's smile (Figures 14 and 15).

DISCUSSIONThe anatomical features of the canine turn it into a key tooth for function and occlusal harmony; acting as a guide in mandibular movements, it stabilizes and protects the joint by reducing the action of the masseter muscles during excentric contacts and given its position in the dental arch, it supports greater occlusal loads. The canine also contributes to the aesthetics of the smile giving support to the upper lip and favoring the facial contour.2,3,5,16,17 Complications of canine traction are: anchylosis, cysts, root resorption of the canine or neighboring teeth, displacement and loss of vitality of the adjacent incisors, recurrent pain, internal resorption, loss of periodontal bone support or the combination of these, which justifies the removal of the canines and its replacement by premolars.1,7,9

Erickson and Kurol mentioned that resorption of the adjacent teeth is a major concern and the most common sequelae in the treatment of impacted canines resulting in the loss of teeth. The case hereby presented was diagnosed as a severe impaction of the maxillary canines and the alternative of orthodontic- surgical traction was not viable since it compromised the integrity of the incisors. In this case report, the surgical removal of the impacted maxillary canines was decided thus eliminating the effects associated with the canines traction and were replaced by the first premolars because they had the size and shape characteristics needed to provide canine guidance by means of premolar guidance or groupfunction. Treatment time was reduced and a good functional, periodontal and aesthetic stabilization was achieved. 3,9,18

In previous results Mirabella reported large differences of aesthetic satisfaction among patients who underwent orthodontic treatment for canine traction, where only 6.5% were dissatisfied. However upon clinical evaluation by the orthodontists satisfaction was only found in a 57%.9

Different authors such as Rosa and Zachrisson recommend the intrusion of the first premolars at the level of the gingival margins and restore them with resins and/or veneer crowns to mimic natural canines and obtain balanced a smile.9 In the case hereby presented, it was chosen group function through first premolars extrusion, deciding to leave a slight discrepancy at the level of the gingival margin by means of a conservative treatment instead of restorative treatments and taking advantage of the fact that the premolars crowns were long with prominent buccal cusps and suitable mesiodistal space.

CONCLUSIONSTreatment of impacted maxillary canines is a great challenge because it involves a multidisciplinary area. However, the option of replacing the canines with the premolars thus eliminating the orthodontic-surgical phase is a viable treatment with good functional periodontal and aesthetic results given that there is an adequate orthodontic management of the final position of the anterior teeth. However, it is not an alternative that can be used in all cases.

This article can be read in its full version in the following page: http://www.medigraphic.com/ortodoncia