The aim of this study was to compare cephalometric results of three and two dimensional surgical predictions in patients that underwent orthognatic surgery. The study involved two groups of 15 to 30 years old patients with craniofacial anomalies. The first group of patients had orthognatic surgery from April 2004 to January 2005. Pre and post-surgical lateral cephalometric measurements were done using Simplant program, (version CMF 8.2 of Materialise, NV, Belgium). The second group of patients had orthognatic surgery from January 1999 to January 2004. Pre and post-surgical lateral cephalometric measurements were done manually. The results of this study showed a more accurate surgical prediction with the Simplant program. In group I (three-dimensional cephalometric measurement) there was not a statistically significant difference between the prediction measurements done before the surgery and those compared with the post-surgically result. In group II, (two-dimensional cephalometric measurements) on the surgical predictions done previously by hand using cut and paste mobiles taken from the patient’s Hospital records, we observed that in the SNA angle and the maxillary length measurements there was a statistically difference (p < .05). Therefore we conclude that the three-dimensional method is more accurate than the two-dimensional method in planning surgical orthognatic procedures.

El objetivo del estudio fue comparar los resultados de la predicción de la cefalometría tridimensional con la bidimensional en pacientes sometidos a cirugía ortognática. El estudio involucró dos grupos de pacientes con anomalías craneofaciales de 15 a 30 años de edad. Al grupo I correspondieron pacientes sometidos a cirugía ortognática del periodo de abril del 2004 a enero del 2005. Se realizaron mediciones cefalométricas pre y posquirúrgicas utilizando el programa Simplant, versión CMF 8.2 de Materialise, NV, Belgium). Al grupo II correspondieron pacientes que ya habían sido sometidos a cirugía ortognática del periodo de enero de 1999 a enero de 2004. Las mediciones cafalométricas se realizaron de forma manual y se tomaron de radiografías laterales de cráneo pre y postquirúrgicas. Los resultados de este estudio demostraron que existe mayor precisión quirúrgica al realizar la predicción con el uso del programa Simplant, demostrando que en el grupo I (medición cefalométrica tridimensional) no existieron diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre las mediciones de la predicción realizada antes de la cirugía al compararlas con el resultado postquirúrgico. En el grupo II (medición cefalométrica bidimensional). Las predicciones quirúrgicas ya realizadas con acetatos (móviles) de forma manual y tomadas de los expedientes clínicos, se observó que la medida del ángulo SNA y de la longitud maxilar obtuvo una p < .05. En conclusión se demostró que la precisión en la planeación del tratamiento quirúrgico por medio del método tridimensional (3D) es mejor que con el método bidimensional (2D).

Facial growth takes place in a gradual and well-ordered manner, however, there are factors that can influence or alter the facial components like bone, cartilage, the dentoalveolar complex and soft tissues.1 Considering that facial growth occurs in the three planes of space (anterior-posterior, vertical and transverse) and taking under consideration the plastic nature of bone, the possibility of remodeling by action of the soft tissues exists in facial deformities.2The limits of orthopedic-orthodontic treatment vary according to the age of the patient since growth can be redirected during its active phase and there can be more changes than the ones that can be made only by dental movement.3 When the patient’s problems are so severe that not even growth modification nor camouflage are a good solution, the only possible treatment is the surgical repositioning of the maxilla or mandible or the repositioning of the dentoalveolar segments to achieve global acceptable results.4

There are five general methods to visualize, plan and predict the surgical results: 1. Hand-tracing with «cut and paste» tracing paper,5 2. Manipulation of the patients photographs to illustrate the treatment objectives, 3. Computer-based diagnosis and treatment planning using a software that produces changes in the soft-tissue profile as a result of the manipulation of digital structures in the lateral radiograph, 4. Computer-based diagnosis and treatment plan using a software that incorporates video imaging with the patient’s lateral cephalogram to predict surgical- orthodontic procedures, visualizing facial changes and allowing the clinician and the patient to interact in relation to the results that can be achieved and 5. Tridimensional computerized technology for the planning and prediction of the orthognatic surgery.5

Bidimensional (2D) computerized programs for surgical treatment planning that combine soft and hard tissue analysis are commercially available and have been used clinically for years, among them Dolphin Imaging, FIY, Quick Ceph, E Ceph, Onyx Ceph, Ortho Vision, Dentofacial Planner, Ceph Scan, NAOL Ortho, Ortho Com and 5 Star Ortho. 2D analysis provides incomplete data by not quantifying the differences in depth and facial form particularly when used on orthognatic and craniofacial surgery.5,6

Nowadays, the uprising of a new specialty in imagenology is being discussed. In this new specialty highly sophisticated technical resources are being offered such as the attainment of the patient’s images based on computerized technologies by means of computerized axial tomography (radiographic cross-sectional views of previously selected areas), magnetic resonance (magnetic field in an emission and reception radio wave frequency system). Several groups have obtained 3D data of the human face using several methods and they have studied growth with them.7,8 In response to the need to represent the craniofacial complex in three dimensions, numerous computer programs have been created such as: Acuscape Medical Imaging System, CSPS, 3Dceph, CAD/CAM,9,10 and Orametrix, Dallas, Tx, USA.10–12 In the 80’s, a process that converted tridimensional digital data into solid objects using liquid photopolymers was developed. As with many new technologies, it was originally used in the industry and later adapted to medical applications and so stereolithographic models developed.12,13

SIM/Plant™ is a software originally designed for dental implant placement planning. It was introduced first by Columbia Scientific Incorporated in 1993 and afterwards it was commercialized by Materialise Company; the operator can create a complete planning for treatment procedures such as distraction by obtaining simultaneous sectional views in three planes of space. With this software one can perform the automatic placement of implants measuring distances, angles and bone density for positioning them in the precise location. Other software tools are surgical predictions which allow the visualization of osteotomies in a virtual model. The movement of these segments can be simulated and it is possible to obtain measurements of bone structures with tridimensional cephalometry.14,15

In 1987 Prospil compared pre and postsurgical (six months after surgery) results with cephalometric hand-tracings in tracing paper using a bidimensional measuring technique for the surgical prediction. He concluded that 60% of the predictions were imprecise when compared to the postsurgical cephalometric measurements; in 83% of the maxillomandibular surgeries and 40% of the maxillary surgeries the surgical predictions were inaccurate in the prediction of soft tissue profiles in relation to postsurgical results.16 In 1997 Kragskow et al. conducted a study in 9 dried skulls of normal persons where they demonstrated the reliability of bidimensional cephalometric radiographs in locating anatomical landmarks when compared to the location of anatomical landmarks in reconstructions of tridimensional images, both obtained with the use of computerized axial tomography (CAT). They also report that tridimensional cephalometry is indicated in patients who present severe asymmetries or craniofacial syndromes and that there are variations in the Basion anatomical landmark.17 Likewise, in 2001 Louis et al. performed a study in 15 adult patients who underwent orthognatic surgery with LeFort I maxillary advancement osteotomy and sagittal osteotomies to advance the mandible. Based on bidimensional cephalometry they demonstrated with their study that the average of the nasolabial angle decrease was not statistically significant and that there is no correlation between the degree of change in the nasolabial angle and the amount of maxillary advancement.18 Also, in 2003 Cousley et al. conducted a study in 25 patients with Class II subdivisions 1 and 2 skeletal discrepancies to whom mandibular advancement surgery was performed. They used the OPAL program (digital bidimensional program) to predict the surgical changes and concluded that the average of the SNA, SNB, LAFH, OJ, OB values were precise when compared to the postsurgical results but they reported individual variations mainly in the Wits measurement (difference between point A and point B measured upon the occlusal plane) which turned out very imprecise. In the MxP/MnP, LPFH and LAFH predictions, the measurements were overrated in relation to the final changes especially in the changes in mandibular rotation.19 However, in 2004 Smith et al. used five computerized bidimensional programs which were: Dentofacial Plann Plus, Dolphin Imaging, Orthoplan, Quick Ceph Image and Vistadent. The programs were used to simulate orthognatic surgery results in the soft tissues of ten patients who presented vertical discrepancies and were later compared with the postsurgical results. The outcome showed that when comparing the simulation with the actual surgical results, the bidimensional program Dentofacial Planner Plus was the best in 79% of the cases when compared to other programs.20 Finally, in 2004 Adams et al. mentioned that cephalometry is a standard used by orthodontists to visualize the skeletal, dental and soft tissue relations. The purpose of their investigations was to evaluate and compare the imaging system in the third dimension (tridimensional cephalometry) with the imaging system in two dimensions (conventional cephalometry). Upon that, they determined which of the two measuring techniques was more accurate and they located 33 anatomical landmarks with both methods in 9 dried skulls analyzing 72 measurements and comparing them to the same measurements taken from the skulls directly. The results showed major variations in the bidimensional method which is currently the gold standard and an over appraisal of the Zy-Gn R measurements in contrast with the tridimensional method (Sculptor Program, Glendora, California) which showed more accuracy and 4 and 5 times more reliability than the bidimensional method.21

The purpose of this investigation was to determine which results of the prediction made with tridimensional and bidimensional cephalometry are more precise when evaluated with the postsurgical result.

The justification was based upon the fact that the Estomathology-Orthodontics Division performs the presurgical evaluation and planning using bidimensional cephalometrics. This investigation was intended to improve the treatment of maxillomandibular discrepancies by comparing the usefulness of conventional bidimensional cephalometry with tridimensional and offer greater precision by introducing new measurement techniques in the orthodontic-surgical planning and treatment.

MethodsThe study design was comparative between two measurement techniques (before and after treatment), open, experimental, ambispective and cross-sectional.

The study consisted in two patient groups 15 to 30 years old with craniofacial anomalies in the Stomatology-Orthodontics Division of the General Hospital «Dr. Manuela Gea Gonzalez».

Group I. Files from patients who underwent orthognatic surgery between April 2004 and January 2005. (The cephalometric measurements and surgical predictions were applied on computer-generated pre and postsurgical tridimensional models with the assistance of the Simplant Program, CMF 8.2 version, Materialise, NV, Belgium). Group II. Files from patients who had already undergone orthognatic surgery from January 1999 to January 2004. (The cephalometric measurements were applied on pre and postsurgical lateral headfilms of already performed surgeries). Fifteen cephalometric measurements were applied to both groups.

Sample size was calculated expecting a difference of 1 mm±.75 on the degree of sliding of the group with bidimensional cephalometry (2D) against tridimensional cephalometry (3D) with an Alfa level of 0.05 and 0.95 and a power calculation of n=16 cases in each group.

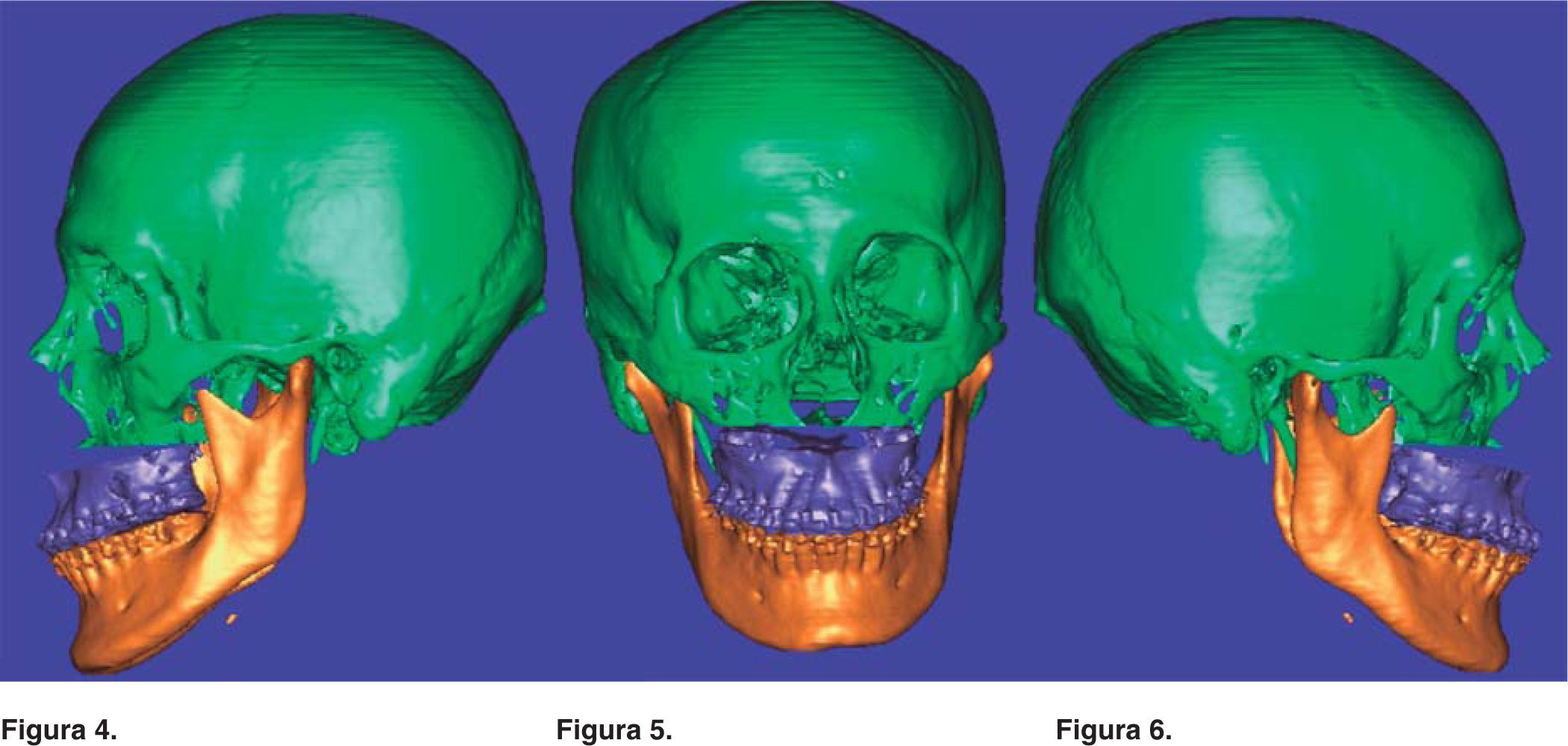

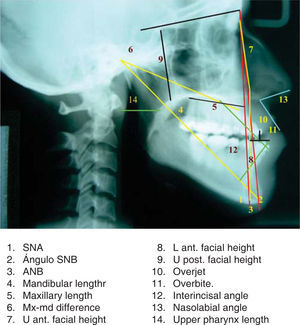

The independent variables analyzed in this study were: age, gender, surgeon, type of surgery and type of osteotomies. The dependent variables were the following cephalometric measurements: SNA angle (S-N/N-A), SNB angle (S-N/N-B), ANB angle, Co-Gn distance, Co-A distance, difference between Co-A and Co-Gn, N-Ena distance, Ena-Me distance, Se-Enp distance, B1-A1 distance, B1-A1 distance, A1 angle, A2/B1-B2 distance between the posterior contour of the soft palate and the posterior pharynx, and the nasolabial angle.

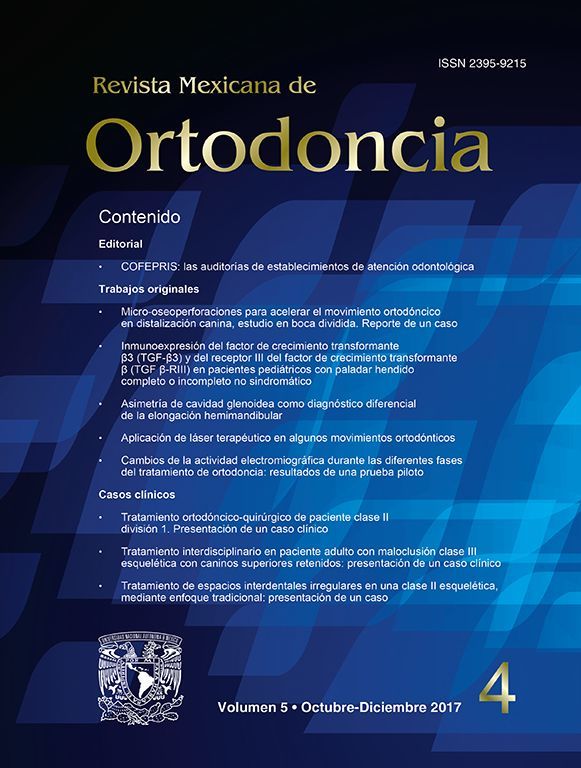

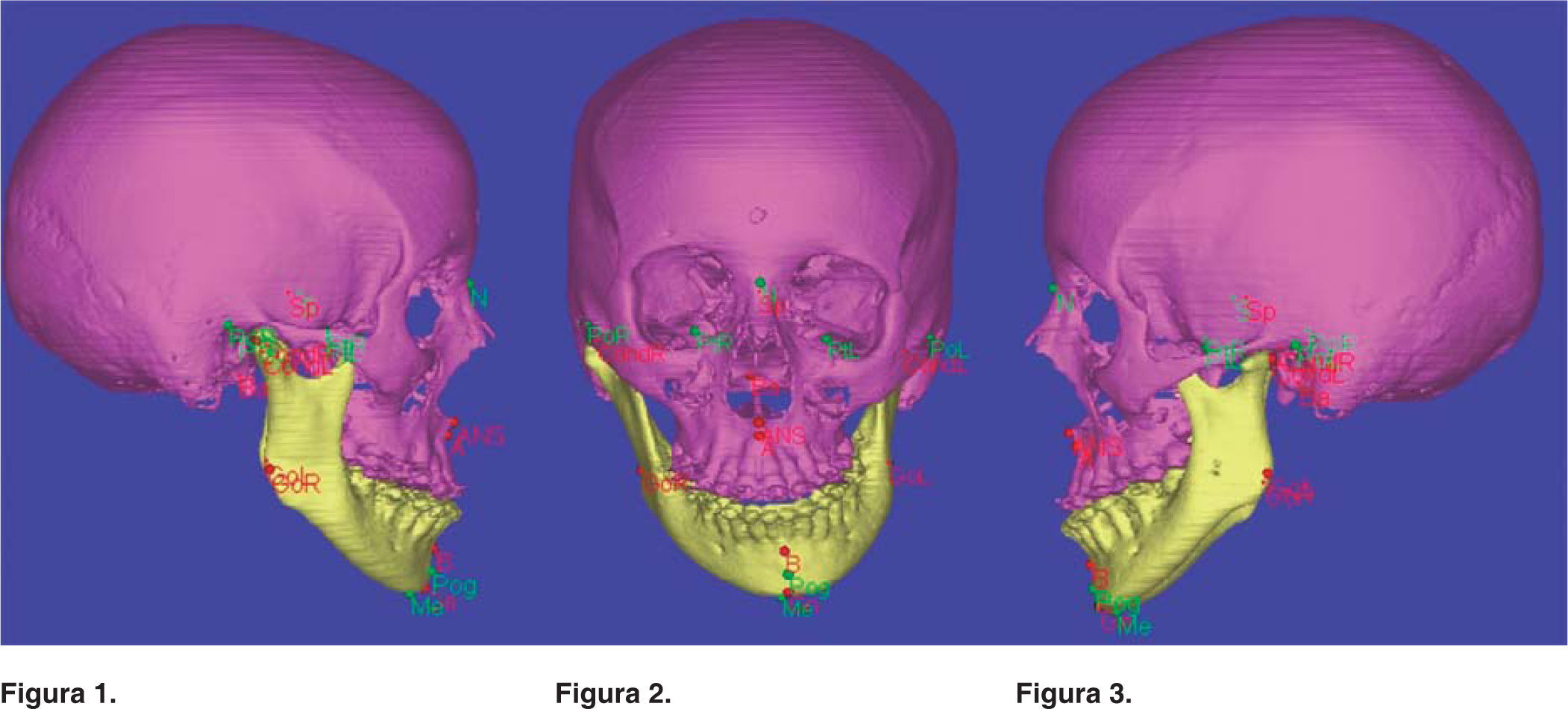

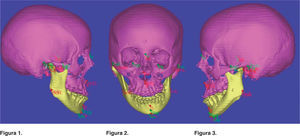

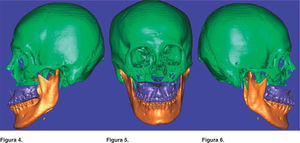

Group I. Once the patient from the study group of the tridimensional cephalometry was selected, the obtained computerized axial tomography was sent to an Imagenology diagnostic center, the information uncompressed images (non-processed information) were filed in DICOM format in a CD (compact disc). (No films are needed), the TAC images were traced and measured with aid from the Simplant program using some measurements from the Ricketts, Steiner and Bigerstaff analysis23,24(Figures 1 to 3). All obtained measurements were interpreted and the data was captured on a database. The diagnosis, surgical treatment plan and surgery virtual simulation were made based on the data base obtained from the tridimensional cephalometry and with the study models and photographs (Figures 4 to 6). The measurements of the virtual surgery were recorded and the data was captured on a database, study model surgery was performed according to the plan and surgical guides were also performed. The surgeon performed the different surgical procedures.25 The patient was sent to had another CAT taken two months after surgery; the images taken from the CAT were traced and measured again with aid from the Simplant program using some measurements from the Ricketts, Steiner and Bigerstaff analysis.23,24 The obtained measurements were collected and captured on a database. Group II. Data from selected files was obtained from the archives of the Stomatology-Orthodontics Division regarding to surgeries performed with bidimensional cephalometry. Cephalometric tracings from the previous surgical prediction taken from the files (hand-traced mobile tracing papers) and from the hand-traced postsurgical lateral cephalometries were measured using some values from the Ricketts, Steiner and Bigerstaff analysis23,24 (Figure 7). All measurements obtained from the surgical prediction and the postsurgical measurements were interpreted and captured on a database. Group I and II. The data obtained from the group in which the surgical plan was performed with tridimensional cephalometry was compared to the data obtained from the postsurgical measurements, the information obtained from files of surgical predictions already performed with bidimensional cephalometry and with data obtained from the postsurgical measurements. In the data validation the Wilcoxon sum of rank test was used, the level of significance was p < .05. All the procedures were in agreement with the Policy of the General Health Law Regarding Health Investigations. It was a mayor risk procedure so an informed consent form was made for the computerized axial tomography uptake.

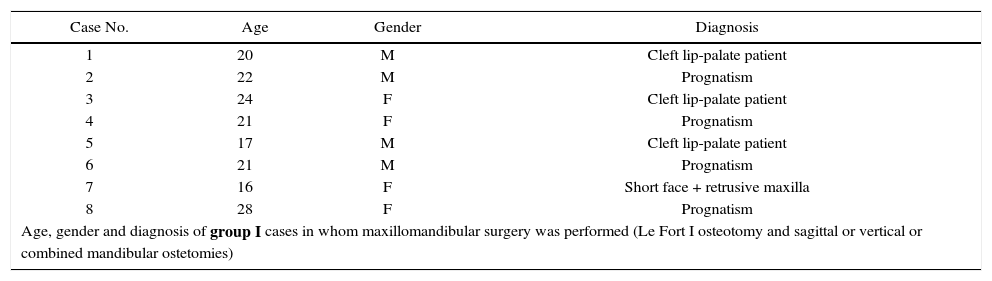

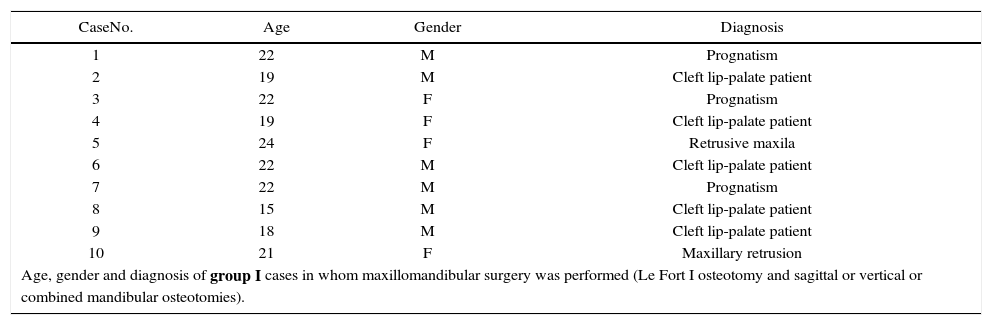

In group I the types of surgery were: eight cases with maxillary surgery (Le Fort I osteotomy) and six cases with maxillomandibular surgeries (Le Fort I osteotomies and sagittal and/or vertical mandibular osteotomies or a combination of both. In group II the types of surgeries were: 10 cases with maxillary surgery (Le Fort I osteotomy) and nine cases with maxillomandibular surgery (Le Fort I osteotomy and sagittal and/or vertical mandibular osteotomies or a combination of both) (Tables IandII).

Age, gender and diagnosis of group I cases in whom maxillary surgery was performed (Le Fort I osteotomy).

| Case No. | Age | Gender | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | M | Cleft lip-palate patient |

| 2 | 22 | M | Prognatism |

| 3 | 24 | F | Cleft lip-palate patient |

| 4 | 21 | F | Prognatism |

| 5 | 17 | M | Cleft lip-palate patient |

| 6 | 21 | M | Prognatism |

| 7 | 16 | F | Short face + retrusive maxilla |

| 8 | 28 | F | Prognatism |

| Age, gender and diagnosis of group I cases in whom maxillomandibular surgery was performed (Le Fort I osteotomy and sagittal or vertical or combined mandibular ostetomies) | |||

| Case No. | Age | Gender | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | F | Prognatism+laterognathia+maxillary retrusion |

| 2 | 26 | M | Prognatism+ laterognathia + maxillary retrusion |

| 3 | 15 | F | Prognatism+ laterognathia +maxillary retrusion |

| 4 | 21 | F | Prognatism+ maxillary retrusion |

| 5 | 17 | F | Prognatism+ laterognathia+ r maxillary retrusion |

| 6 | 18 | F | Prognatism+ maxillary retrusion |

Age, gender and diagnosis of group II cases in whom maxillary surgery was performed (Le Fort I osteotomy).

| CaseNo. | Age | Gender | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22 | M | Prognatism |

| 2 | 19 | M | Cleft lip-palate patient |

| 3 | 22 | F | Prognatism |

| 4 | 19 | F | Cleft lip-palate patient |

| 5 | 24 | F | Retrusive maxila |

| 6 | 22 | M | Cleft lip-palate patient |

| 7 | 22 | M | Prognatism |

| 8 | 15 | M | Cleft lip-palate patient |

| 9 | 18 | M | Cleft lip-palate patient |

| 10 | 21 | F | Maxillary retrusion |

| Age, gender and diagnosis of group I cases in whom maxillomandibular surgery was performed (Le Fort I osteotomy and sagittal or vertical or combined mandibular osteotomies). | |||

| Case No. | Age | Gender | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 | M | Prognatism+ laterognathia+ maxillary retrusion |

| 2 | 24 | F | Prognatism+ laterognathia+ maxil-lary retrusion |

| 3 | 20 | M | Prognatism+ maxillary retrusion |

| 4 | 16 | F | Prognatism+ laterognathia+ maxillary retrusion |

| 5 | 19 | M | Prognatism+ laterognathia + maxillary retrusion |

| 6 | 24 | F | Prognatism+ maxillary retrusion |

| 7 | 17 | F | Prognatism+ maxillary retrusion |

| 8 | 23 | M | Prognatism+ laterognathia + maxillary retrusion |

| 9 | 21 | F | Prognatism+ laterognathia + maxil- |

In group I the rank of age was from 16 to 28 years, the average was 21.12 and the standard deviation was 3.8 on patients on whom maxillary surgery was performed. The age rank was from 15 to 26 years, the average was 19.1 and the standard deviation was 3.8 on patients on whom maxillomandibular surgery was performed (Tables IandII). In group II the age rank was 15 to years old, the average was 20.4 and the standard deviation was 2.6 on the maxillary surgery cases and the age rank was 15 to 26 years old, the average was 19.8 and the standard deviation was 3.4 on the cases on whom maxillomandibular surgery was performed. Every patient was operated by the attending physicians (Tables IandII).

In group I: 4 (50%) were men and 4 (50%) were female in cases where maxillary surgery was performed and one (16.6%) was man and 5 (83%) were women where maxillomandibular surgery was performed. In group II: 6 (60%) were men and 4 (40%) were female which underwent maxillary surgery and 4 (44%) were males and 5 (55%) were female in the cases where maxillomandibular surgery was performed. All patients underwent surgery by doctors assigned (Tables IandII).

DiscussionIn this study tridimensional technology (computer-generated tridimensional models made with the Simplant program CMF 8.2 version from Materialise, NV, Belgium) was applied, the conversion of the obtained data from he computerized axial tomography in DICOM format with 1mm slices was performed and the patient was asked to sign an informed consent due to the radiation exposure. The tridimensional images have been applied o visualize the soft tissue and bone deformities and the data manipulation permits the integration of the applied knowledge to tridimensional models.26,27

The results from the study demonstrate that the two measuring techniques used for the surgical prediction are effective when compared to the postsurgical results on groups I and II (tridimensional and bidimensional cephalometry). These results coincide with the statements from Prospil, Cousley, Smith, Kragskow et al.16,17,19,20

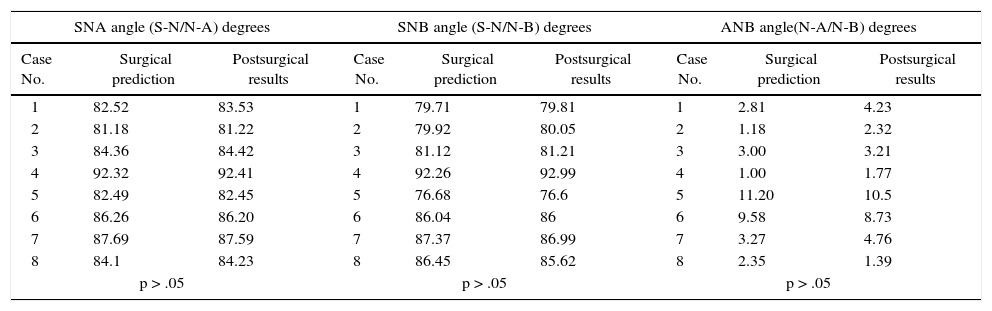

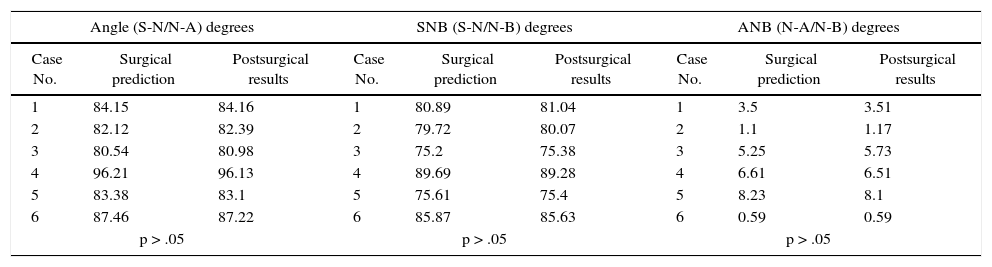

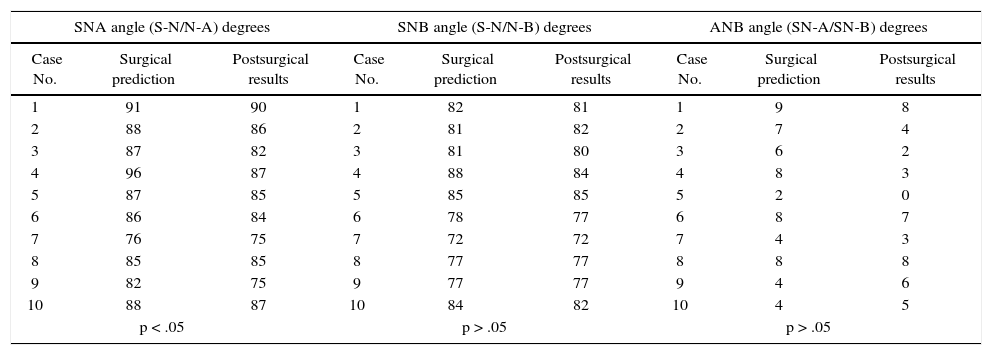

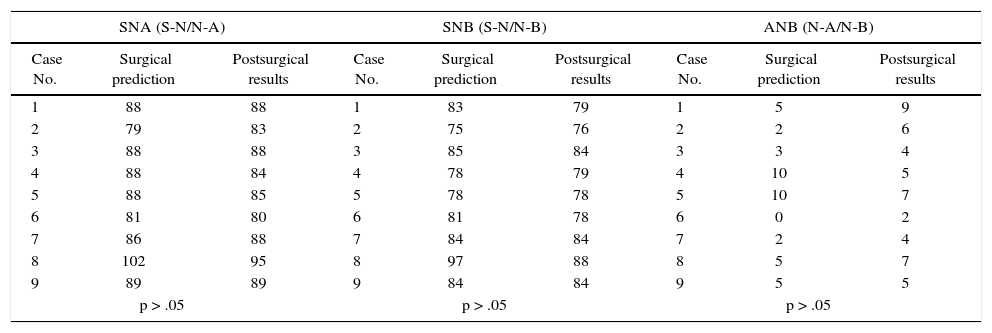

The results from our study state that there is more surgical precision when performing the prediction with the Simplant program, demonstrating that in group I (tridimensional cephalometric measurement) there were no statistically significant differences between the measurements from the prediction performed before the surgery when compared to the postsurgical result. In group II (bidimensional cephalometric measurement) when performing the prediction with (mobile) tracing papers manually it was observed that the SNA angle measurement and the effective maxillary length obtained a p < .05 significance (p is the probability that the observed difference of each group is random)21 (Tables III to VI).

Group I, maxillary surgery results (tridimensional cephalometry).

| SNA angle (S-N/N-A) degrees | SNB angle (S-N/N-B) degrees | ANB angle(N-A/N-B) degrees | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 82.52 | 83.53 | 1 | 79.71 | 79.81 | 1 | 2.81 | 4.23 |

| 2 | 81.18 | 81.22 | 2 | 79.92 | 80.05 | 2 | 1.18 | 2.32 |

| 3 | 84.36 | 84.42 | 3 | 81.12 | 81.21 | 3 | 3.00 | 3.21 |

| 4 | 92.32 | 92.41 | 4 | 92.26 | 92.99 | 4 | 1.00 | 1.77 |

| 5 | 82.49 | 82.45 | 5 | 76.68 | 76.6 | 5 | 11.20 | 10.5 |

| 6 | 86.26 | 86.20 | 6 | 86.04 | 86 | 6 | 9.58 | 8.73 |

| 7 | 87.69 | 87.59 | 7 | 87.37 | 86.99 | 7 | 3.27 | 4.76 |

| 8 | 84.1 | 84.23 | 8 | 86.45 | 85.62 | 8 | 2.35 | 1.39 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Effective mandibular length (Co-GnL) mm | Effective maxillary length | Maxillo-mandibular difference (Co-Gn/Co-AL) mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 127.8 | 127.52 | 1 | 102.97 | 103.16 | 1 | 24.83 | 24.36 |

| 2 | 145.19 | 145.61 | 2 | 107.56 | 107.69 | 2 | 37.63 | 37.92 |

| 3 | 122.14 | 122.9 | 3 | 94.10 | 96.13 | 3 | 28.6 | 26.77 |

| 4 | 130.99 | 131.1 | 4 | 101.71 | 101.77 | 4 | 29.28 | 29.28 |

| 5 | 125.51 | 125.18 | 5 | 102.00 | 101.92 | 5 | 23.51 | 23.24 |

| 6 | 128.88 | 128.68 | 6 | 96.80 | 96.60 | 6 | 32.08 | 32.08 |

| 7 | 130.05 | 130 | 7 | 102.44 | 102.10 | 7 | 27.6 | 27.9 |

| 8 | 143.9 | 143.7 | 8 | 105.32 | 105.10 | 8 | 28.18 | 28.6 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Effective mandibular length (Co-GnL) mm | Effective maxillary length | Maxillo-mandibular difference (Co-Gn/Co-AL) mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 125.16 | 125.38 | 1 | 99.00 | 99.88 | 1 | 26.1 | 25.41 |

| 2 | 142.1 | 144.44 | 2 | 104.8 | 105.04 | 2 | 37.3 | 39.4 |

| 3 | 123.43 | 125.93 | 3 | 90.26 | 90.69 | 3 | 33.17 | 35.29 |

| 4 | 129.92 | 130.59 | 4 | 96.33 | 97.42 | 4 | 33.59 | 33.17 |

| 5 | 127.06 | 126.97 | 5 | 101.57 | 101.12 | 5 | 25.49 | 25.85 |

| 6 | 128.86 | 128.59 | 6 | 96.24 | 95.62 | 6 | 32.62 | 32.92 |

| 7 | 131.14 | 131.1 | 7 | 103.83 | 103.70 | 7 | 27.31 | 27.4 |

| 8 | 140.16 | 139.9 | 8 | 101.00 | 101.10 | 8 | 39.16 | 38.8 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Lower anterior facial height | AUpper posterior facial height (Se-Enp) mm | Anterior superior facial height | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N-Me) Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | (N-Me) Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | (N-Me) Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 59.29 | 60.27 | 1 | 37.53 | 37.73 | 1 | 64.92 | 64.88 |

| 2 | 73.11 | 73.41 | 2 | 39.44 | 38.44 | 2 | 67.68 | 67.46 |

| 3 | 71.42 | 71.63 | 3 | 34.16 | 33.06 | 3 | 57.56 | 57.82 |

| 4 | 58.96 | 59.99 | 4 | 32.52 | 32.32 | 4 | 52.31 | 52.28 |

| 5 | 72.71 | 72.51 | 5 | 31.31 | 31.23 | 5 | 65.83 | 65.67 |

| 6 | 69.09 | 68.96 | 6 | 35.48 | 35.3 | 6 | 67.38 | 67.83 |

| 7 | 62.66 | 61.84 | 7 | 31.51 | 31.11 | 7 | 55.23 | 55.12 |

| 8 | 63.54 | 63 | 8 | 39.42 | 39.21 | 8 | 66.84 | 66.82 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Overjet (B1-A1) mm | Overbite (B1-A1) mm | Interincisal angle (A1-A2/B1-B2) degrees | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 2.12 | 2.92 | 1 | 2.88 | 2.33 | 1 | 137.53 | 137.85 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2.16 | 2.12 | 2 | 118.67 | 118.86 |

| 3 | 2.96 | 2.54 | 3 | 3.13 | 2.83 | 3 | 124 | 114.6 |

| 4 | 1.68 | 1.44 | 4 | 1.94 | 2.18 | 4 | 133.26 | 109.35 |

| 5 | 2.78 | 2.26 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 121.83 | 120.04 |

| 6 | 1.88 | 2.12 | 6 | 2.13 | 1.98 | 6 | 119.74 | 116.78 |

| 7 | 2.63 | 2.98 | 7 | 2.88 | 2.34 | 7 | 124.24 | 110.35 |

| 8 | 3.33 | 2.83 | 8 | 3.12 | 2.96 | 8 | 123.25 | 117.28 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Upper pharynx Distance between the posterior contour of he soft palate and posterior pharyngeal wall | Nasolabial angle (degrees) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 6.33 | 9.83 | 1 | 80.92 | 86.80 |

| 2 | 11.69 | 16.55 | 2 | 67.29 | 61.64 |

| 3 | 6.03 | 8.43 | 3 | 76.73 | 98.01 |

| 4 | 11.67 | 15.64 | 4 | 75.82 | 77.43 |

| 5 | 6.92 | 13.36 | 5 | 114.09 | 117.11 |

| 6 | 12.02 | 16.03 | 6 | 66.73 | 71.07 |

| 7 | 10.91 | 15.90 | 7 | 50.83 | 77.09 |

| 8 | 9.24 | 17.22 | 8 | 52.38 | 81.06 |

| p < .05 | p > .05 | ||||

Group I, results of maxillomandibular surgery (tridimensional cephalometry).

| Angle (S-N/N-A) degrees | SNB (S-N/N-B) degrees | ANB (N-A/N-B) degrees | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 84.15 | 84.16 | 1 | 80.89 | 81.04 | 1 | 3.5 | 3.51 |

| 2 | 82.12 | 82.39 | 2 | 79.72 | 80.07 | 2 | 1.1 | 1.17 |

| 3 | 80.54 | 80.98 | 3 | 75.2 | 75.38 | 3 | 5.25 | 5.73 |

| 4 | 96.21 | 96.13 | 4 | 89.69 | 89.28 | 4 | 6.61 | 6.51 |

| 5 | 83.38 | 83.1 | 5 | 75.61 | 75.4 | 5 | 8.23 | 8.1 |

| 6 | 87.46 | 87.22 | 6 | 85.87 | 85.63 | 6 | 0.59 | 0.59 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Effective mandibular length (Co-GnL) | Effective maxillary height (Co-AL) mm | Maxillo-mandibular difference (Co-Gn/Co-AR) mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 127.46 | 127.67 | 1 | 97.12 | 97.47 | 1 | 30.34 | 30.2 |

| 2 | 122.92 | 123.14 | 2 | 93.97 | 94.17 | 2 | 28.95 | 28.97 |

| 3 | 118.98 | 119.08 | 3 | 95.36 | 95.65 | 3 | 23.62 | 23.43 |

| 4 | 137.07 | 136.99 | 4 | 101.65 | 101.43 | 4 | 35.42 | 35.56 |

| 5 | 126.38 | 126.28 | 5 | 103.35 | 103.21 | 5 | 23.03 | 23.07 |

| 6 | 123.92 | 123.84 | 6 | 90.27 | 89.92 | 6 | 33.65 | 33.92 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Effective mandibular length | Effective maxillary height | Maxillo-mandibular difference (Co-Gn/Co-AR) mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Surgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 120.45 | 120.65 | 1 | 90 | 90.94 | 1 | 30.45 | 29.81 |

| 2 | 121.18 | 121.71 | 2 | 94.92 | 95.13 | 2 | 26.26 | 26.58 |

| 3 | 121.56 | 121.62 | 3 | 95.5 | 95.82 | 3 | 26.06 | 25.8 |

| 4 | 135.93 | 135.53 | 4 | 102.46 | 102.42 | 4 | 33.47 | 33.11 |

| 5 | 124.43 | 124.12 | 5 | 101.33 | 101.33 | 5 | 23.1 | 22.79 |

| 6 | 124.12 | 123.95 | 6 | 90.1 | 89.99 | 6 | 34.02 | 33.96 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Anterior upper facial height (N-Ena) mm | Lower anterior facial height (Ena-Me) | Upper posterior facial height (Se-Enp) mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 50.35 | 50.55 | 1 | 72.23 | 72.85 | 1 | 35.94 | 35.84 |

| 2 | 61.72 | 61.69 | 2 | 69.56 | 71.17 | 2 | 30.28 | 30.14 |

| 3 | 65.58 | 65.43 | 3 | 66.99 | 67.4 | 3 | 38.67 | 38.57 |

| 4 | 64.89 | 64.99 | 4 | 70.9 | 71.7 | 4 | 27.59 | 27.46 |

| 5 | 53.97 | 53.78 | 5 | 73.2 | 73.37 | 5 | 27.38 | 27.06 |

| 6 | 60.43 | 60.23 | 6 | 71.7 | 71.19 | 6 | 39.36 | 39.54 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Overbite (B1-A1) mm | Overbite (B1-A1) mm | Interincisal angle(A1-A2/B1-B2) degrees | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.Case | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | No.Case | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | No.Case | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 2.96 | 2.54 | 1 | 2.28 | 2.13 | 1 | 112.76 | 128.5 |

| 2 | 2.34 | 2.26 | 2 | 2.65 | 2.43 | 2 | 122.94 | 119.43 |

| 3 | 1.17 | 2.12 | 3 | 3.23 | 2.31 | 3 | 117.66 | 108.96 |

| 4 | 1.95 | 2.34 | 4 | 2.67 | 3.12 | 4 | 127.86 | 109.64 |

| 5 | 3.2 | 3.13 | 5 | 3.43 | 2.97 | 5 | 105.75 | 117.81 |

| 6 | 2.87 | 2.76 | 6 | 2.67 | 3.17 | 6 | 107.23 | 122.7 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Upper pharynx Distance between the posterior contour of the soft palate and the posterior phayingeal wall | Nasolabial angle (degrees) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 7.37 | 8.77 | 1 | 80.83 | 95.31 |

| 2 | 14.03 | 10 | 2 | 78.53 | 83.28 |

| 3 | 9.32 | 11.92 | 3 | 99.67 | 104.88 |

| 4 | 9.19 | 10.73 | 4 | 108.65 | 121.17 |

| 5 | 8.15 | 11.11 | 5 | 95.29 | 100.36 |

| 6 | 10.21 | 13.82 | 6 | 106.13 | 115.48 |

| p > .05 | p < .05 | ||||

Group II, results of maxillary surgery (bidimensional cephalometry).

| SNA angle (S-N/N-A) degrees | SNB angle (S-N/N-B) degrees | ANB angle (SN-A/SN-B) degrees | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 91 | 90 | 1 | 82 | 81 | 1 | 9 | 8 |

| 2 | 88 | 86 | 2 | 81 | 82 | 2 | 7 | 4 |

| 3 | 87 | 82 | 3 | 81 | 80 | 3 | 6 | 2 |

| 4 | 96 | 87 | 4 | 88 | 84 | 4 | 8 | 3 |

| 5 | 87 | 85 | 5 | 85 | 85 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| 6 | 86 | 84 | 6 | 78 | 77 | 6 | 8 | 7 |

| 7 | 76 | 75 | 7 | 72 | 72 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| 8 | 85 | 85 | 8 | 77 | 77 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 9 | 82 | 75 | 9 | 77 | 77 | 9 | 4 | 6 |

| 10 | 88 | 87 | 10 | 84 | 82 | 10 | 4 | 5 |

| p < .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Efective maxillary length (Co-A) mm | Maxilo-mandibular difference (Co-Gn/Co-A) mm | Upper anterior face height (N-Ena) mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 82 | 80 | 1 | 34 | 35 | 1 | 59 | 62 |

| 2 | 80 | 77 | 2 | 29 | 33 | 2 | 61 | 59 |

| 3 | 71 | 72 | 3 | 32 | 34 | 3 | 62 | 60 |

| 4 | 69 | 75 | 4 | 33 | 35 | 4 | 48 | 54 |

| 5 | 76 | 74 | 5 | 35 | 41 | 5 | 57 | 54 |

| 6 | 82 | 80 | 6 | 26 | 30 | 6 | 69 | 70 |

| 7 | 80 | 83 | 7 | 27 | 21 | 7 | 60 | 59 |

| 8 | 71 | 75 | 8 | 29 | 20 | 8 | 60 | 57 |

| 9 | 82 | 80 | 9 | 41 | 31 | 9 | 58 | 66 |

| 10 | 66 | 67 | 10 | 22 | 30 | 10 | 59 | 55 |

| p < .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Lower anterior face height (Ena-Me) mm | Upper posterior face height (Se-Enp) mm | Overjet (B1-A1) mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 82 | 80 | 1 | 53 | 55 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | 80 | 77 | 2 | 51 | 50 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | 71 | 72 | 3 | 45 | 47 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | 69 | 75 | 4 | 46 | 50 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 5 | 76 | 74 | 5 | 48 | 47 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| 6 | 82 | 80 | 6 | 54 | 41 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| 7 | 80 | 83 | 7 | 47 | 47 | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| 8 | 71 | 75 | 8 | 47 | 43 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| 9 | 82 | 80 | 9 | 50 | 50 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| 10 | 66 | 67 | 10 | 47 | 44 | 10 | 2 | 2 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Overbite (B1-A1) mm | Interincisal angle (A1-A2/B1-B2) degrees | Upper pharynx Distance between the posterior contour of the soft palate and posterior pharyngeal wall mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 128 | 129 | 1 | 11 | 20 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 126 | 123 | 2 | 15 | 18 |

| 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 117 | 122 | 3 | 17 | 17 |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 136 | 135 | 4 | 12 | 21 |

| 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 140 | 143 | 5 | 14 | 15 |

| 6 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 141 | 133 | 6 | 15 | 19 |

| 7 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 144 | 147 | 7 | 12 | 14 |

| 8 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 133 | 134 | 8 | 10 | 17 |

| 9 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 132 | 134 | 9 | 8 | 11 |

| 10 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 123 | 120 | 10 | 9 | 15 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p < .05 | ||||||

| Nasolabial angle (degrees) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 105 | 105 |

| 2 | 90 | 94 |

| 3 | 77 | 90 |

| 4 | 32 | 71 |

| 5 | 89 | 53 |

| 6 | 80 | 87 |

| 7 | 89 | 84 |

| 8 | 110 | 96 |

| 9 | 140 | 70 |

| 10 | 87 | 85 |

| p > .05 | ||

Grupo II, results maxilo-mandibular surgery (bidimensional cephalometry).

| SNA (S-N/N-A) | SNB (S-N/N-B) | ANB (N-A/N-B) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical results |

| 1 | 88 | 88 | 1 | 83 | 79 | 1 | 5 | 9 |

| 2 | 79 | 83 | 2 | 75 | 76 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| 3 | 88 | 88 | 3 | 85 | 84 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 88 | 84 | 4 | 78 | 79 | 4 | 10 | 5 |

| 5 | 88 | 85 | 5 | 78 | 78 | 5 | 10 | 7 |

| 6 | 81 | 80 | 6 | 81 | 78 | 6 | 0 | 2 |

| 7 | 86 | 88 | 7 | 84 | 84 | 7 | 2 | 4 |

| 8 | 102 | 95 | 8 | 97 | 88 | 8 | 5 | 7 |

| 9 | 89 | 89 | 9 | 84 | 84 | 9 | 5 | 5 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Effective mandibular length (Co-Gn) mm | Effective maxillary height (Co-A) mm | Maxilo-mandibular difference (Co-Gn/Co-A) mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical result | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical result | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical result |

| 1 | 147 | 145 | 1 | 104 | 105 | 1 | 33 | 30 |

| 2 | 125 | 125 | 2 | 93 | 100 | 2 | 32 | 25 |

| 3 | 142 | 142 | 3 | 102 | 100 | 3 | 40 | 42 |

| 4 | 118 | 126 | 4 | 86 | 87 | 4 | 32 | 39 |

| 5 | 135 | 136 | 5 | 102 | 101 | 5 | 33 | 35 |

| 6 | 141 | 135 | 6 | 94 | 90 | 6 | 47 | 45 |

| 7 | 131 | 124 | 7 | 89 | 92 | 7 | 42 | 32 |

| 8 | 140 | 140 | 8 | 107 | 108 | 8 | 33 | 32 |

| 9 | 126 | 121 | 9 | 92 | 90 | 9 | 34 | 31 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Upper anterior facial height (N-Ena) mm | Lower anterior facial height (N-Me) mm | Upper posterior facial height (Se-Enp) mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical result | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical result | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical result |

| 1 | 66 | 68 | 1 | 82 | 82 | 1 | 56 | 55 |

| 2 | 61 | 63 | 2 | 78 | 80 | 2 | 45 | 43 |

| 3 | 69 | 67 | 3 | 85 | 90 | 3 | 57 | 59 |

| 4 | 65 | 59 | 4 | 75 | 80 | 4 | 51 | 53 |

| 5 | 67 | 66 | 5 | 85 | 92 | 5 | 51 | 53 |

| 6 | 61 | 63 | 6 | 82 | 77 | 6 | 48 | 67 |

| 7 | 53 | 54 | 7 | 81 | 84 | 7 | 54 | 51 |

| 8 | 33 | 32 | 8 | 76 | 81 | 8 | 50 | 51 |

| 9 | 56.5 | 54 | 9 | 76 | 79 | 9 | 48 | 50 |

| p > .05 | p > .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Overjet (B1-A1) mm | Overbite (B1-A1) mm | Interincisal angle (A1-A2/B1-B2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical result | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical result | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical result |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 123 | 134 |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 121 | 133 |

| 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 120 | 126 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 123 | 142 |

| 5 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 137 | 126 |

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 132 | 135 |

| 7 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 135 | 136 |

| 8 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 145 | 146 |

| 9 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 145 | 136 |

| p < .05 | p < .05 | p > .05 | ||||||

| Upper pharynx Distance between the posterior contour of the soft palate and posterior pharyngeal wall mm | Nasolabial angle (degrees) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical result | Case No. | Surgical prediction | Postsurgical result |

| 1 | 18 | 18 | 1 | 90 | 104 |

| 2 | 15 | 17 | 2 | 90 | 110 |

| 3 | 15 | 19 | 3 | 115 | 127 |

| 4 | 14 | 16 | 4 | 70 | 69 |

| 5 | 18 | 22 | 5 | 100 | 115 |

| 6 | 10 | 15 | 6 | 75 | 90 |

| 7 | 13 | 15 | 7 | 107 | 118 |

| 8 | 13 | 20 | 8 | 100 | 96 |

| 9 | 15 | 19 | 9 | 85 | 102 |

| p < .05 | p < .05 | ||||

In relation to the evaluation of soft tissue pre and postsurgical changes, the measurements of the nasolabial angle from groups I and II increased significantly in patients on whom maxillomandibular surgery was performed (p < .05) when compared to the measurements of the postsurgical result. Other measurement that was significantly increased in group I is the length of the upper pharynx wall in patients on whom maxillary surgery was performed (p < .05) when compared with the post-surgical result’s measurements, it was also observed that in group II the measurements of the upper pharynx wall increased significantly in patients who underwent maxillary and mandibular surgery (p < .05). This corresponds to the studies performed by Louis et al.18

ConclusionsThis study demonstrated that the precision in surgical treatment planning is greater with the use of tridimensional prediction (3D) than with bidimensional method (2D).

In analyzing the presurgical soft tissues and comparing them with the postsurgical results an increase in length of the upper pharynx was observed. There was also an increase in the nasolabial angle with both methods.

The present study introduced the use of computerized digital models, adding a new dimension for evaluating and planning more accurately the surgical treatment by providing presurgical manipulation of all the facial components and analyzing facial harmony of patients with craniofacial anomalies.