The aim of this study was to evaluate clinical differences and similarities between anorexia nervosa (AN) patients with and without a history of obesity. We evaluated 108 patients (10–18 years old) with the restricting or purging subtype of AN, treated at a public referral facility in Brazil. To evaluate clinical characteristics, we used a standardized psychiatric interview, the Development and Well-Being Assessment, the Children's Global Assessment Scale, the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q), and body mass index (BMI)-for-age percentile. The mean age was 14.8±2.5 years, and 95 (88.0%) of the patients were female. Of the 108 patients evaluated, 78 (72.2%) had restrictive AN and 23 (21.3%) had a history of obesity. Patients with and without a history of obesity were similar in terms of age at onset, time from symptom onset to treatment, duration of treatment, impact of the disease on global functioning, and comorbidities. At treatment initiation, those with a history of obesity were at a higher BMI-for-age percentile and scored higher on the Weight Concern subscale of the EDE-Q. We conclude that severe cases of AN can occur in patients with and without a history of obesity with no differences in terms of the baseline characteristics and the duration of treatment. The significantly higher BMI-for-age percentiles amongst patients with a history of obesity (at treatment initiation) suggests that the urge for treatment shouldn't be based on BMI percentile only.

El objetivo de este estudio fue identificar las diferencias clínicas entre pacientes con anorexia nerviosa (AN) con y sin antecedentes de obesidad. Se evaluaron 108 pacientes (10–18 años de edad) con AN del subtipo restrictivo o purgativo, tratados en un centro público de referencia en Brasil. Para evaluar las características clínicas, se utilizaron una entrevista estandarizada psiquiátrica, el Development and Well-Being Assessment, la Children's Global Assessment Scale, el Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q), y el percentil del índice de masa corporal (IMC) para la edad. La edad media fue de 14.80±2, años, y 95 (88.00%) de los pacientes eran del sexo femenino. De los 108 pacientes, 78 (72.20%) tenían AN restrictiva y 23 (21.30%) tenían antecedentes de obesidad. Los pacientes con y sin antecedentes de obesidad eran similares en términos de edad de inicio de la enfermedad, tiempo desde el inicio de los síntomas hasta el inicio del tratamiento, duración del tratamiento, impacto de la enfermedad en el funcionamiento general y comorbilidades. Al inicio del tratamiento, los pacientes con antecedentes de obesidad estaban en un percentil más alto de IMC para la edad y puntuaron más alto en la subescala preocupación por el peso del EDE-Q. En conclusión, casos graves de AN pueden ocurrir en pacientes con y sin antecedentes de obesidad.

Childhood obesity is a public health problem that affects 30–45 million children worldwide (Stettler, 2004). According to the Household Budget Survey conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), between 1974 and 2009, the prevalence of overweight among adolescents (defined as individuals 10–19 years of age) in Brazil increased from 3.7% to 21.7% for males and from 7.6% to 19.4% for females (IBGE, 2012). Obesity is associated with a number of acute diseases that have high mortality rates, such as acute myocardial infarction, as well as with chronic progressive diseases, including diabetes and hypertension. As a result, various strategies of prevention and treatment of weight control problems have been used by health professionals and by the community. Such strategies include launching advertising campaigns; providing information on the caloric value of foods, prescribing low-calorie diets and exercise programs; and encouraging the consumption of “light” foods. Experts question the efficacy and effectiveness of these strategies, especially because they can encourage excessive concern about weight and body image, body dissatisfaction, weight gain, and poor weight control practices (Ferrari, 2011; Neumark-Sztainer, Paxton, Hannan, Haies, & Story, 2006; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2007; Neumark-Sztainer, Wall, Story & Van Den Berg, 2008). Various studies have shown that the emphasis on monitoring appearance and weight can promote disordered eating behaviors and the risk of developing an eating disorder (ED) increases in proportion to the amount of weight gained (Goldschmidt, Aspen, Sinton, Tanofsky-Kraff & Wilfley, 2008) and one of the most severe forms of such changes in behavior are eating disorders (Goldschmidt et al., 2008).

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revised (DSM-IV-TR), diagnoses of eating disorders include anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa full and partial syndromes (known as the eating disorders not otherwise specified) (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2005). The basic characteristics of AN are extreme weight loss resulting from a restrictive diet, an unbridled quest for thinness, the use of other restrictive methods (including excessive exercise), and, in some cases, purging (by self-induced vomiting or by using laxatives, diuretics, or enemas), all of which are aimed at controlling weight and countering body image dissatisfaction (APA, 2006; World Health Organization [WHO], 1993). The restrictive subtype of AN is characterized by the absence of binge eating and purging, whereas binge eating, purging, or both are seen in the purging subtype (APA, 2005).

Among adolescents girls and adult women, the full form of AN (meeting all of the diagnostic criteria) has a prevalence of 0.40–0.90%, whereas that of the partial form (meeting only some of those criteria, the exceptions being underweight and amenorrhea) is 2.80–6.60% (APA, 2006; Fleitlich-Bilyk & Lock, 2008; Swanson, Crow, LeGrange, Swendedsen & Merikangas, 2011). Studies investigating samples of adult or adolescent patients have shown that more than half of such patients present with the partial form of AN, which is more difficult to diagnose and has the same impact as does the full form, both forms requiring appropriate treatment (Ángel & Ángel, 2003; Nicholls, 1999; Nicholls, Chater & Lask, 2000; Workgroup For Classification of Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents [WCEDCA], 2007). Medium- and long-term studies have shown that a diagnosis of AN increases the risk of premature death. The crude mortality rate among individuals with AN being 5–20%, which is 6–12.80 times higher than that reported for the general population of individuals of the same age and gender (APA, 2006; Eckert, Halmi, Marchi, Grove & Crosby, 1995; Herzog et al., 2000; Keel et al., 2003; Papadopoulos, Ekbom, Brandt & Ekselius, 2009; Pinzon & Nogueira, 2004). Among individuals with AN, there is also high morbidity, which results in significant deficits in psychological, biological and social functioning, as well as having long-term consequences, such as short stature, osteopenia, osteoporosis, and infertility. In addition, the burden of AN, on the family and on society, is high, not only in terms of the cost of treatment but also in terms of lost productivity and the consequent cost of supporting individuals with the disorder (Moya & Cominato, 2008; Prince et al., 2007). As in cases of obesity, failure to identify and treat individuals with AN at an early age increases the likelihood that the disorder will carry over into adulthood (Rohde & Banaschewski, 2008).

Despite the increasing prevalence of obesity and the severity of AN, few studies have compared AN and obesity, however, a recent study found that individuals with AN have more dysfunctional eating attitudes that individuals with obesity (Alvarenga, Koritar, Pisciolaro, Mancini, Cordás & Scagliusi, 2014). Furthermore, various authors have cited obesity as a risk factor for eating disorders, although most such studies have dealt with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder (Fairburn, Welch, Doll, Davies & O'Connor, 1997; Fairburn et al., 1998; Field et al., 2012; McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2009; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2007). Although eating disorders can increase the risk of obesity and obesity might be a risk factor for eating disorders (one perpetuating the other), eating disorders and obesity are considered distinct diseases and are most often treated independently (Ferrari, 2011; Goldschmidt et al., 2008; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2007; Neumark-Sztainer, Wall, Story & Sherwood, 2009). The scientific community is still attempting to establish the clinical features of eating disorders in youths with a history of obesity, primarily to identify the need for adjustments to the diagnostic and treatment processes. The aim of this study was to evaluate the differences and similarities between AN adolescent patients with and without a history of obesity, in terms of the diagnosis, symptoms, impact on overall functioning, age at onset of the eating disorder, time from symptom onset to treatment, nutritional status, psychiatric comorbidities, and duration of treatment.

MethodsStudy participantsThis was a cross-sectional study conducted under the auspices of the Programa de Atendimento, Ensino e Pesquisa em Transtornos Alimentares na Infância e Adolescência (PROTAD, Treatment, Education, and Research Program for Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents) of the University of São Paulo School of Medicine Hospital das Clínicas Institute of Psychiatry, located in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. The sample consisted of 108 patients diagnosed with full or partial AN, as defined in the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2005), who were enrolled in the PROTAD between November 2001 and April 2013. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of São Paulo School of Medicine Hospital das Clínicas (Protocol no. 0800/08).

Materials and instrumentsPatient data were collected at PROTAD enrollment. Eating disorders and other psychiatric comorbidities were diagnosed by means of a psychiatric interview and the application of the Brazilian Portuguese-language version of the Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA). The English-language version of the DAWBA has previously been used in the evaluation of children and adolescents (Goodman, Ford, Richards, Gatward & Meltzer, 2000). The DAWBA comprises a set of questionnaires and interviews, the objective of which is the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence, based on the criteria established in the DSM-IV (APA, 2005) and in the tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (Fleitlich-Bilyk & Goodman, 2004).

The impact that such disorders had on the overall functioning of the patients was measured by the Children's Global Assessment Scale (Schaffer et al., 1983).

To assess the frequency and severity of eating disorder symptoms in the last month, we used the version translated to Portuguese and back translated to English of Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) with validation in progress, which consists of 28 questions, distributed among four subscales: Eating Concern; Shape Concern; Weight Concern; and Restraint. From the sum of the scores on the four subscales, we obtain a global score, which is an indicator of disordered eating behavior (Fairburn, 2008; Fairburn & Beglin, 1994).

Nutritional status at the initiation of treatment was assessed by the body mass index (BMI)-for-age percentile and was classified as underweight, normal weight, overweight or obese, according to World Health Organization criteria (De Onis et al., 2007). Data related to a history of obesity (prior to diagnosis of the eating disorder) were obtained from patient health records or from the reports of patients or their legal guardians.

The age at onset of the eating disorder was defined as the month in which the symptoms first appeared. The time from symptom onset to treatment (i.e., to enrollment in the PROTAD) was calculated in months. The duration of treatment, also calculated in months, was defined as the interval between enrollment in the PROTAD and discharge from treatment. The clinical, psychiatric, nutritional, and family histories, compiled through the use of standardized PROTAD questionnaires, assisted in obtaining additional information or in cases in which there are missing data.

Statistical analysisFor the statistical analysis, we used the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 14.0 (SPSS). Values of p≤.05 were considered statistically significant. Continuous variables are reported as means and standard deviations, whereas categorical variables are reported as absolute and relative frequencies. To assess associations between dichotomous categorical variables, we used Fisher's exact test when two such variables were compared and the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test when three or more such variables were compared, whereas we used the chi-square to identify associations between non-dichotomous categorical variables. In the analysis of the EDE-Q scores, we used t-tests to compare pairs of numerical variables and two-way analysis of variance to compare three or more numerical variables.

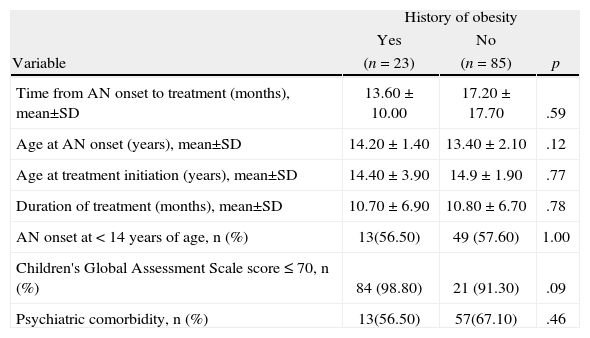

ResultsWe surveyed 108 patients diagnosed with AN, 78 (72.20%) with the restrictive subtype and 30 (27.80%) with the purging subtype. The mean age was 14.80±2.50 years, and 95 (88.00%) of the patients were female. Of those 108 patients, 23 (21.30%) had a history of obesity prior to receiving the diagnosis of AN. We found no statistically significant difference between the patients with and without a history of obesity (p=.58), regardless of the AN subtype (restrictive or purging). Table 1 shows the comparison between the AN patients with and without a history of obesity, in terms of the baseline characteristics and the duration of treatment.

Comparison between AN patients with and without a history of obesity.

| History of obesity | |||

| Yes | No | ||

| Variable | (n=23) | (n=85) | p |

| Time from AN onset to treatment (months), mean±SD | 13.60±10.00 | 17.20±17.70 | .59 |

| Age at AN onset (years), mean±SD | 14.20±1.40 | 13.40±2.10 | .12 |

| Age at treatment initiation (years), mean±SD | 14.40±3.90 | 14.9±1.90 | .77 |

| Duration of treatment (months), mean±SD | 10.70±6.90 | 10.80±6.70 | .78 |

| AN onset at < 14 years of age, n (%) | 13(56.50) | 49 (57.60) | 1.00 |

| Children's Global Assessment Scale score ≤ 70, n (%) | 84 (98.80) | 21 (91.30) | .09 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity, n (%) | 13(56.50) | 57(67.10) | .46 |

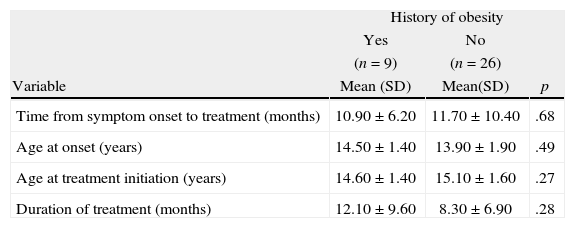

At treatment initiation, the BMI-for-age percentile was significantly higher among the patients with a history of obesity than among those without (p=.01). Only 44 (40.7%) of the patients completed the EDE-Q. Regardless of the subtype of AN, there were no statistically significant differences between patients who completed the EDE-Q with those who did not for any of the variables evaluated, except for time from symptom onset to treatment, which was significantly longer among those who completed the questionnaire (p=.04). Due to the small number of patients diagnosed with the purging type of AN (n=9), our analysis of the EDE-Q scores in order to compare the patients with and without a history of obesity included only the patients with the restrictive type of AN (n=35). Among the patients with the restrictive type of AN who completed the EDE-Q, there were no significant differences between those with and without a history of obesity, in terms of the age at onset, time from symptom onset to treatment, age at treatment initiation, and duration of treatment (Table 2).

Comparison between patients with and without a history of obesity among those with the restrictive subtype of AN who completed the EDE-Q.

| History of obesity | |||

| Yes | No | ||

| (n=9) | (n=26) | ||

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Mean(SD) | p |

| Time from symptom onset to treatment (months) | 10.90±6.20 | 11.70±10.40 | .68 |

| Age at onset (years) | 14.50±1.40 | 13.90±1.90 | .49 |

| Age at treatment initiation (years) | 14.60±1.40 | 15.10±1.60 | .27 |

| Duration of treatment (months) | 12.10±9.60 | 8.30±6.90 | .28 |

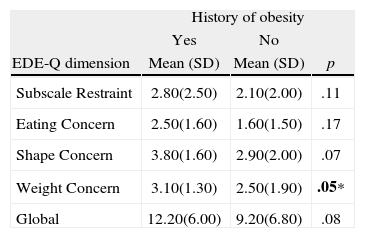

The EDE-Q scores of the patients with the restrictive type of AN (subscale and global scores) are shown in Table 3. One notable finding is that only the score on the Weight Concern subscale differed significantly between the patients with and without a history of obesity (p=.05).

Comparison between patients with and without a history of obesity among those with the restrictive subtype of AN, in terms of the EDE-Q scores.

| History of obesity | |||

| Yes | No | ||

| EDE-Q dimension | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p |

| Subscale Restraint | 2.80(2.50) | 2.10(2.00) | .11 |

| Eating Concern | 2.50(1.60) | 1.60(1.50) | .17 |

| Shape Concern | 3.80(1.60) | 2.90(2.00) | .07 |

| Weight Concern | 3.10(1.30) | 2.50(1.90) | .05* |

| Global | 12.20(6.00) | 9.20(6.80) | .08 |

In the present study, patients with the restrictive type of AN predominated, accounting for 72.20% of the sample. Younger patients are more likely to have restrictive eating symptoms (McVey, Tweed & Blackmore, 2004) and our study sample was relatively young (mean age, 14.8 years).

In our sample, regardless of the prevalence of obesity among adolescents in Brazil to be similar between females and males (IBGE, 2012), the percentage of women is higher than men, according to the literature of the expected prevalence ratio of TAs man: women ranging from 1:6 to 1:10 (APA, 2006).We found that the frequency of a history of obesity among the AN patients with the restrictive subtype was similar to that observed among those with the purging subtype. The small number of patients diagnosed with the purging subtype might explain why this finding differs from those of other studies, in which AN patients with a history of obesity have been shown to be more likely to exhibit purging behaviors (Fairburn et al., 1997; Fairburn et al., 1998; Field et al., 2012; McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2009; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2007). In addition, most of the studies on the relationship between obesity and eating disorders have involved patients with bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder (Fairburn et al., 1997; Fairburn et al., 1998; Field et al., 2012; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2007), as if those were the most common eating disorders among obese individuals. In the present study, we demonstrated that obese youths may also develop AN. When youths present with weight loss, clinicians should attempt to determine whether that weight loss is being achieved by inappropriate eating behaviors, which can be accompanied by guilt, fear, and anxiety, and is motivated by the relentless pursuit of an ever lower body weight. As an isolated finding, weight loss would not be a good indicator of health (Fairburn et al., 1997; Fairburn et al., 1998; Field et al., 2012; Hebebrand & Herpertz-Dahlmann, 2008; McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2009; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2007; Neumark-Sztainer, 2012), which calls attention to the dangers of obesity prevention campaigns that focus on weight loss or on achieving an ideal weight.

Another important finding of the present study was that the AN patients with a history of obesity were at a higher BMI-for-age percentile than were those without such a history. In clinical trials, such patients may go unnoticed and not be diagnosed or treated properly. In the literature, a downward trend in the BMI-for-age percentile curve, especially when there are more than two lines, even within a wide percentile range of normality, indicates acute pathology and an increased risk of developing an eating disorder (Nicholls, 1999; Nicholls et al., 2000; WCEDCA, 2007). This information is so important that, in the new diagnostic classification of eating disorders, in the DSM-V (APA, 2013), the parameters of weight loss or percentage of weight loss have been replaced by an emphasis on restrictive eating behavior that would result in weight loss or failure to achieve the weight expected for the age, sex and height of the individual (APA, 2013). Low body weight or low BMI at the initiation of treatment plays no proven role in the course of AN (Fichter & Quadflieg, 1999; Gowers & Doherty, 2007; Herzog, Nussbaum & Marmor, 1996;Steinhausen, Seidel & Metzke, 2000; Steinhausen, 2002; Strober, Freeman & Morrel, 1997). However, patients with a history of obesity can have an apparently normal nutritional status when they present for treatment of an eating disorder, which can mask the potential severity of the disorder and risk of death, leading clinicians to believe that the treatment of such cases will be simple.

More than half of the individuals in our sample, regardless of the history of obesity, developed the eating disorder before 14 years old. Eating disorders that begin before 14 years of age are designated early-onset eating disorders (Ángel & Ángel, 2003; Bryant-Waugh & Lask, 1995, 2007; Cooper, Watkins, Bryant-Waugh & Lask, 2002). Individuals with early-onset eating disorders tend to lose a large amount of weight in a short time, imposing drastic dietary restrictions, as well as using formal and informal exercise regimens, to achieve their “target” weight (Pinzon, Turkiewicz, Monteiro, Koritar & Fleitlich-Bilyk, 2013). This indicates that such individuals, regardless of their nutritional status, can engage in such harmful behavior at an early age. In parallel, the age at onset of AN appears to be associated with the severity of the disease. The occurrence of eating disorders in the prepubertal period appears to worsen the prognosis (Bryant-Waugh & Lask, 2007; Fichter & Quadflieg, 1999; Gowers & Doherty, 2007; Herzog et al., 1996; Hoek, 2002; Overas, Winje & Lask, 2008). It is important not to underestimate the risk posed by restrictive diets, excessive exercise and harmful weight control behaviors in this age group, even among obese patients.

In our study sample, the time from symptom onset to treatment was similar between the patients with and without a history of obesity and was in agreement with the 11–15 months reported in studies conducted in developed countries (Couturier & Lock, 2006; Herpertz-Dahlmann, Müller, Herpertz & Heussen, 2001; Lock, Agras, Bryson & Kraemer, 2005; Zonnevylle-Bender et al., 2004). A longer time from symptom onset to treatment seems to be associated with unfavorable outcomes, including mortality (Fichter & Quadflieg, 1999; Herzog et al., 1996; Herzog et al., 2000; Steinhausen et al., 2000; Steinhausen, 2002; Treat et al., 2005). Because weight loss is desirable in obese patients, weight change related to an eating disorder could go unnoticed or even be encouraged in such patients, thereby delaying their entry into treatment for the latter. Among the patients evaluated in the present study, it seems that harmful weight control behaviors and an abrupt change in nutritional status (with its clinical consequences) were identified by family members and health professionals, even in the patients with a history of obesity.

We found no statistically significant difference between the patients with and without a history of obesity in terms of the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity.

Both groups showed a high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity, as has previously been demonstrated in patients with AN, as well as in patients with obesity (APA, 2006; Berkman, Lohr & Bulik, 2007; Marcos & Wildes 2009; Milos, Spindler & Schnyder, 2004; Swanson et al., 2011; Wentz, Gillberg, Gillberg & Rastam, 2001). An interesting study would be one comparing the profiles, in terms of psychiatric comorbidities, of patients with obesity; patients with obesity and an eating disorder; and non-obese patients with an eating disorder. Psychiatric comorbidity is considered a risk factor for poor prognosis in patients with an eating disorder (APA, 2006; Berkman et al., 2007; Milos et al., 2004; Swanson et al., 2011; Wentz et al., 2001), as was found to be the case in the present study, regardless of the history of obesity.

We found that AN had a significant impact on the overall functioning of the patients evaluated here, regardless of psychiatric comorbidities and the history of obesity, as represented by scores lower than 70 on the Children's Global Assessment Scale. That cut-off score indicates at least a moderate degree of functional impairment in most social areas or severe functional impairment in a specific area (Schaffer et al., 1983). Satisfaction with weight loss, which typically leads to improved overall functioning in obese patients, does not occur in those who develop AN. Patients with AN that goes untreated remain permanently dissatisfied with their weight, which has broad and profound effects on their quality of life. Despite perhaps having played a role in resolving the obesity, this persistent dissatisfaction results in functional deficits and can serve as a parameter that allows health professionals to identify patients with AN.

One of the great challenges of treating AN in adolescence is to restore normal development, with remission or complete resolution of the disordered eating behaviors. That is the criterion for discharge from the PROTAD, which provides multidisciplinary treatment. Within this treatment model, the patients evaluated in the present study, regardless of the history of obesity, required an average of 11 months of treatment in order to achieve symptom remission and resume their normal development. It could be assumed that in the imagination of previously obese patients, improving the symptoms of the AN would cause them to return to being overweight, resulting in a resurgence of their eating disorder. However, we found that having had the actual experience of obesity did not increase the duration of treatment. This might be due to the fact that the PROTAD uses therapeutic strategies tailored to each patient. However, it is important to help patients to recognize and differentiate between a real fear of becoming obese and the exaggerated fear associated with AN, seeking a new health status together with patients and their families.

Studies indicate that overweight and obese individuals score 30–40% higher on the Weight Concern and Shape Concern subscales of the EDE-Q (Aardoom, Dingemans, Sot Op't Landt & Van Furth, 2012; Ro, Reas & Rosenvinge, 2012). In this study, when we applied the EDE-Q in order to evaluate the symptoms of the restrictive subtype of AN in patients with and without a history of obesity, we found that the two groups differed significantly only in their scores on the Weight Concern subscale. This difference might be attributable to a greater fear of regaining weight among the patients with a history of obesity. A fear of becoming obese again is common among previously obese individuals.

Despite the limitations of the present study (the small number of patients diagnosed with the purging subtype and the small size of the sample as a whole), our results show that AN patients with and without a history of obesity are, in general, quite similar. This underscores the idea that a history of obesity has no ameliorating effect on the severity, symptomatology, and prognosis of AN. It is essential that health professionals pay close attention to patients with a history of obesity, conducting systematic evaluations of their behaviors, thoughts, and feelings over the course of treatment, in order to identify behaviors that put them at risk for developing AN (i.e., behaviors not focused solely on weight loss). Fear of gaining weight despite resolution of obesity, permanent body dissatisfaction, and deficits rather than gains in social functioning, as well as maintenance or progression of a restrictive diet accompanied by excessive exercise, should result in patient referral for evaluation by an eating disorder specialist.

There is a need for further studies comparing eating disorder patients with and without a history of obesity, in terms of their clinical characteristics. Such studies should evaluate that distinction not only by AN subtype but also by the type of eating disorder, comparing bulimia nervosa with AN.