We describe cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa (CBT-BN) with a Latina woman that incorporates culturally relevant topics.

MethodA single case report of a 31-year-old monolingual Latina woman with BN describes the application of a couple-based intervention adjunctive to CBT-BN.

ResultsThe patient reported no binge and purge episodes by session 20 and remained symptom free until the end of treatment (session 26). Improvement was observed in the Eating Disorders Examination (EDE) comparing baseline (EDE=5.74) with post treatment (EDE=1.25).

ConclusionsThe case illustrates how cultural adaptations such as including a family member, being flexible on topics and scheduling, and providing culturally relevant interventions can lead to successful completion of a course of therapy and facilitate ongoing interventions to ensure continued recovery.

Describimos la terapia cognitiva conductual para la bulimia nerviosa (TCC-BN) con una mujer latina incorporando tópicos que son culturalmente relevantes.

MétodoUn estudio de caso de una mujer latina monolingüe de 31 años con BN en el que se describe la incorporación de una intervención de pareja adjunta al TCC-BN.

ResultadosPara la sesión 20, la paciente no reportó atracones ni conductas purgativas y continuó libre de síntomas hasta el final del tratamiento (sesión 26). La mejoría se observó en el Eating Disorders Examination (EDE) al comparar la evaluación de base (EDE=5.74) con la evaluación post tratamiento (EDE=1.25).

ConclusiónEl caso ilustra como adaptaciones culturales como incluir a un miembro familiar, ser flexible en los tópicos y en la agenda de trabajo, y proveer intervenciones culturalmente relevantes pueden llevar a una exitosa culminación de un proceso terapéutico y facilita las intervenciones que se llevan a cabo para asegurar un continuo proceso de recuperación.

The few extant studies on eating disorders (EDs) in Latinos/as suggest prevalences on par with Caucasians in the United States (U.S.) (Alegria, Woo, Cao, Torres, Meng, & Striegel-Moore et al., 2007; Caballero, Sunday, & Halmi, 2003; Cachelin, Rebeck, Veisel, & Striegel-Moore, 2001; Hiebert, Felice, Wingard, Muñoz & Ferguson 1988). However, specialized bilingual and culturally sensitive services for EDs are scarce. The misconception that EDs only occur in white upper-middle class females and the widespread use of questionnaires that have been developed and tested primarily on Caucasian populations could contribute to clinician bias (Smolak & Striegel-Moore, 2001) or underreporting of cases. There is clearly a need for more detailed research on the assessment and treatment of EDs for the Latino population in the U.S.

Full recognition of cultural values is a key element to providing adequate treatment for EDs (Kempa & Thomas, 2000). The inclusion of cultural values has been documented to be critical in the treatment of depression (Duarte-Velez, Bernal, & Bonilla, 2010) and diabetes (Metghalchi, Rivera, Beeson, Firek, De Leon, Balcazar, & Cordero-Macintyre, 2008) in the Latino population. Although evidence-based interventions developed and tested with Caucasian individuals may be appropriate for most ethnic minority individuals, the use of protocols or guidelines that consider culture and context combined with evidence-based care is likely to facilitate engagement in treatment and has the potential to enhance outcomes (Domenech Rodriguez, Baumann, & Schwartz, 2011; Miranda, Bernal, Lau, Kohn, Hwang, & La Framboise, 2005; Shea, Cachelin, Uribe, Striegel, Thompson, & Wilson, 2012).

The case report presented in this article was part of a National Institute of Mental Health NIMH-funded research study “Engaging Latino Families in Eating Disorders Treatment” (Reyes-Rodriguez, Bulik, Hamer, & Baucom, 2013). This case was part of formative work exploring the role of the family in EDs recovery in adult Latina women. The main objective of this case study was to explore the feasibility of family involvement, the appropriateness of assessment procedures, and the need for cultural adaptation of treatment for the target population, while considering language, immigration, level of acculturation and cultural values, lack of health insurance, and coordination of medical and family support using Latino community services. Permission was obtained from the patient and family member to present de-identified information for publication. Additional protection for the anonymity was achieved by omitting specific descriptive information about the case. This study was approved by the biomedical Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Case IllustrationCase ReportReferral information. A 31-year-old monolingual Latina was referred to the PAS Project (“Promoviendo una Alimentación Saludable” or Promoting Healthy Eating) by a community mental health clinic where she had been seen for one visit but was referred due to lack of specialized ED services. The search for appropriate Spanish language ED services for this patient took seven months, during which time she received no treatment.

Demographic information. The patient began treatment in November, 2010. During the study, the patient was living with a partner and two children under age five. Her highest education achieved was ninth grade. She emigrated from a Latin American country at the age of 25 to the U.S. and was undocumented. Due to her migratory status, health insurance was not available. At the time of the study in order to take care of her children, the patient did not work outside of the home.

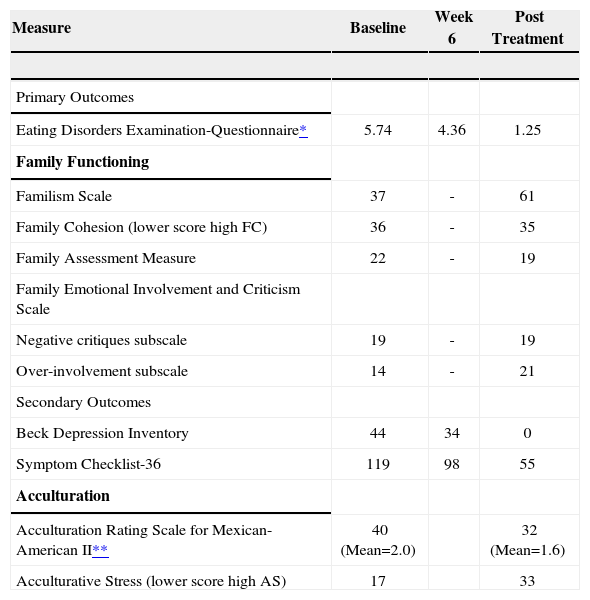

Assessment and diagnosis. A clinical diagnostic interview was conducted to assess the ED, comorbidity, family dynamics (e.g., family cohesion, family involvement), and acculturation. All measures were administered in Spanish with instruments previously validated in the Latino population. Scores obtained at baseline, week 6, and post treatment assessments are presented in Table 1.

Primary and secondary outcomes across the treatment in single case Latina woman

| Measure | Baseline | Week 6 | Post Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcomes | |||

| Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire* | 5.74 | 4.36 | 1.25 |

| Family Functioning | |||

| Familism Scale | 37 | - | 61 |

| Family Cohesion (lower score high FC) | 36 | - | 35 |

| Family Assessment Measure | 22 | - | 19 |

| Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale | |||

| Negative critiques subscale | 19 | - | 19 |

| Over-involvement subscale | 14 | - | 21 |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||

| Beck Depression Inventory | 44 | 34 | 0 |

| Symptom Checklist-36 | 119 | 98 | 55 |

| Acculturation | |||

| Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican-American II** | 40 (Mean=2.0) | 32 (Mean=1.6) | |

| Acculturative Stress (lower score high AS) | 17 | 33 |

Eating Disorders Examination (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993). The EDE, which is the gold standard measure, was used to establish the DSM-IV diagnosis of eating disorders. The EDE has been found to have high validity and reliability and is sensitive to change. We used the Spanish version of the EDE which has been adapted for use with Latina women (Reyes-Rodríguez, Rosselló, & Calaf, 2005).

Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q Fairburn and Beglin,1994). The EDE-Q was adapted by Elder and Grilo (2007) with monolingual Spanish speaking Latina women. This self-report version of the EDE-Q assesses many of the same variables as the interview. The Spanish version test-retest reliability Spearman rho ranged from 0.71 to 0.81 (Elder & Grilo, 2007). A Global score of ≥ 2.30 is used as a threshold of eating disturbances (Hilbert, de Zwaan, & Braehler, 2012).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961). The BDI evaluates the severity of depressive symptoms. This Spanish version is a reliable measure that has been used with Latinos/as in major outcome studies of depression (Bernal, Bonilla, & Santiago, 1995). The Cronbach’s alpha obtained for the BDI Spanish version was 0.88 (Bonilla, Bernal, Santos, & Santos, 2004). Levels of depression were defined using the BDI score as mild (BDI=18-19); moderate (BDI=20-26); and severe (BDI ≥ 27).

The Symptom Checklist-36 (SCL-36; McNeill, Greenfield, Attkison, & Binder, 1989). To explore other psychiatric symptomatology the SCL-36 was used. This measure generates six separate factor scores (depression, somatization, hostility-suspiciousness, phobic anxiety, and interpersonal sensitivity) and one global index of psychopathology. Levels of psychiatric symptoms were defined as none (SCL-36= 0-76); low (SCL-36=77-106); moderate (SCL-36= 107-136) and severe (SCL-36=≥ 137). Also, this measure was validated and tested with a Latino population, resulting in a Cronbach’s alpha of .94 (Bernal, Bonilla, & Bellido, 1995; Bonilla et al., 2004).

Familism Scale (FS; Sabogal, Marín, & Otero-Sa-bogal,1987). Family dynamics were evaluated with the FS, which measures values and attitudes toward the family, focusing on identification and attachment between the family members and feelings of family loyalty and reciprocity. The FS has 14 items and, three factors emerge from this scale: family obligations (perceived obligation to provide material and emotional support to the members of the extended family), perceived support from the family, and family as referents (behavioral and attitudinal). These factors revealed adequate reliability coefficients (0.76, 0.70, and 0.64 respectively). The scale exists in both English and Spanish and has been used with various cultural groups. Higher score represents greater familism.

The Family Cohesion scale (FC; Alegria, Vila, Woo, Canino, Takeuchi et al., 2004). The FC is a seven item measure focused on elements of family closeness and communication such as whether the respondent considers family togetherness to be very important. Higher scores represent lesser levels of family cohesion as compared to lower scores. The FC was used in the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) with a Cronbach’s alpha of .83 among the Latino population (Alegria et al., 2004).

The Family Assessment Measure (FAM; Skinner, Steinhauer, & Santa-Barbara, 1995; Skinner, Steinhauer, & Sitarenios, 2000). The FAM is a self-report instrument designed to measure family functioning. The original instrument evaluates strengths and weaknesses of functioning through 30 items divided into 9 sub-scales: task accomplishment, role performance, affective expression, control, values, norms, communication, and environment. We used the Brief FAM, which is a short version of each of the three FAM-III versions (General, Self, and Dyadic) with a Cronbach’s alpha of .93 (Skinner, Steinhauer, & Sitarenios, 2000). This measure has been used previously with Latino population (Riggs & Greenberg, 2004).

The Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale (FEICS; Shields, Franks, Harp, McDaniel, & Campbell, 1992). The FEICS was designed to measure family expressed emotion from a family member’s perspective. This scale measures perceived negative criticism and over-involvement in the family. A high score in both sub-scales implies higher criticism and higher emotional involvement, respectively. Internal consistency for the English and Spanish (Martínez & Rosselló, 1995) versions, respectively, of this instrument are 0.74 and 0.54. The internal consistency for the Emotional Involvement Intensity subscale was 0.82 and 0.71 for the Perceived Criticism subscale.

Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican-American II (ARSMA-II; Cuellar & Maldonado, 1995). The level of acculturation was assessed with ARS-MA-II. This measure is designed to assess multi-faceted integrative acculturation which includes; language use and preference, ethnic identity and classification, cultural heritage and behaviors, and ethnic interaction. ARSMA-II consist of 25 statements with a 5 point rating scale from “not at all” to “extremely often” with higher scores indicating greater frequency. The internal reliability of this measure using the Cronbach’s alpha is .88 (Cuellar & Maldonado, 1995). Acculturation is defined by Pérez, Voelz, Pettit and Joiner (2002) as the “assimilation of a different culture to one’s own culture with the ultimate goal of minimizing the differences between cultures”.

The Acculturative Distress Scale (ADS; Alegria et al., 2004). The ADS was used to measure the stress of culture change that results from immigrating to the U.S. This scale consists of eight items and has been tested mostly with Mexican American samples and has dichotomous response categories of “yes” (1) or “no” (5). This measure was used in the NLAAS study with a Cronbach’s alpha of .70 in the Latino population. Acculturation stress results from the changes that emerge from the acculturation process and is related with mental health symptoms in diverse cultures (Perez et al., 2002).

Clinical presentationThe patient presented with BN-purging type (BN-P) with a reported frequency of one to three binge and purge episodes per day and a body mass index (BMI) of 29.1 kg/m2. Age of onset of BN was 18, and at age 22, she received one year treatment for BN in her home country. In addition to BN, the patient reported depressive and post-traumatic symptoms due to a car accident she was involved in months before starting treatment in the PAS Project. Baseline scores were 44 on the BDI (severe depression) and 119 on the SCL-36 (moderate symptomatology). Previous treatment in the U.S. included intervention for postpartum depression after her first pregnancy. Some ED behaviors (e.g., fasting and purging) were also present during her second pregnancy. After the birth of her first child, the patient was referred by her pediatrician for mental health assessment as a preventive intervention due to potential child maltreatment (she tried to strangle her child). After the second birth, because her depression symptoms recurred, she was again referred to mental health services. The patient sought treatment for her depression in the community mental health clinic where she discussed her ED behaviors for the first time in the U.S.

Family backgroundThe patient came from a large family of 8 siblings. She described constant fighting between her parents and reported a history of physical and emotional maltreatment by her mother. The patient left home at the age of 15 and reported several suicide attempts during her childhood and adolescence, using pills and running uncontrollably from her house in the hope that something bad would happen to her. She reported several sexually-related traumatic experiences throughout adolescence and during adulthood.

Acculturation level and stressThe patient and her partner were first generation immigrants in the U.S. According to the ARSMA-II scale (Cuellar & Maldonado, 1995), the patient has a Mexican-oriented bicultural orientation (mean=2.0) and although her immigration was six years prior to presentation, her level of acculturative stress at baseline was high (AS=17). Her acculturative stress was related to family isolation, problems interacting with other people because of language, difficulty finding a job, loss of the respect that she had had in her country, a sense of being mistreated by others due to her language barrier, and her fear of being deported during any contact with government agencies, including health services.

Treatment InterventionOur approach was built around a core of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Bulimia Nervosa (CBT-BN) developed by Fairburn, Marcus, and Wilson (Fair-burn & Wilson, 1993). CBT-BN is an individual, semi-structured, problem-oriented intervention, focused on the patient’s present and future rather than his or her past.

Phase I cognitive perspective about bulimia nervosa (Sessions1-8)The goal of phase I was to introduce the patient to the treatment process, structure, goals, and the cognitive model of BN. Given her considerable depression, anxiety, and insomnia, the history of psychiatric medications was discussed via consultation with the nurse practitioner; the patient was receptive to taking Prozac 20mg by session 4. This dose was maintained throughout treatment. Due to her past history of suicide attempts and her level of depression, suicidal ideation was assessed weekly throughout the treatment intervention.

During the first session, a brief history of childhood, family dynamic, traumas, and other relevant life experiences were discussed. This initial comprehensive assessment contributed to a clinical conceptualization and to personalize the cognitive BN model of symptom maintenance. The core areas addressed during the first 6 sessions were built around the preplanned eating disorders-related CBT interventions, but included additional topics, such as parenting skills, deemed necessary for the patient to engage and remain in treatment. This initial treatment plan was broadened because there were additional issues facing the patient that required immediate therapeutic attention. These were: (a) her history of traumatic events (i.e., sexually related trauma), and (b) parenting skill deficits (e.g., lack of consistency in discipline and parenting authority). Her sexual abuse and other traumatic experiences were identified as a critical issue associated with her low self-esteem, body dissatisfaction, and problems with marital intimacy. Problems with parenting skills were considered as a source of distress and a distraction from the patient’s ability to engage in CBT-BN. As such, parenting issues were included as a brief intervention which also included the partner in session 5.

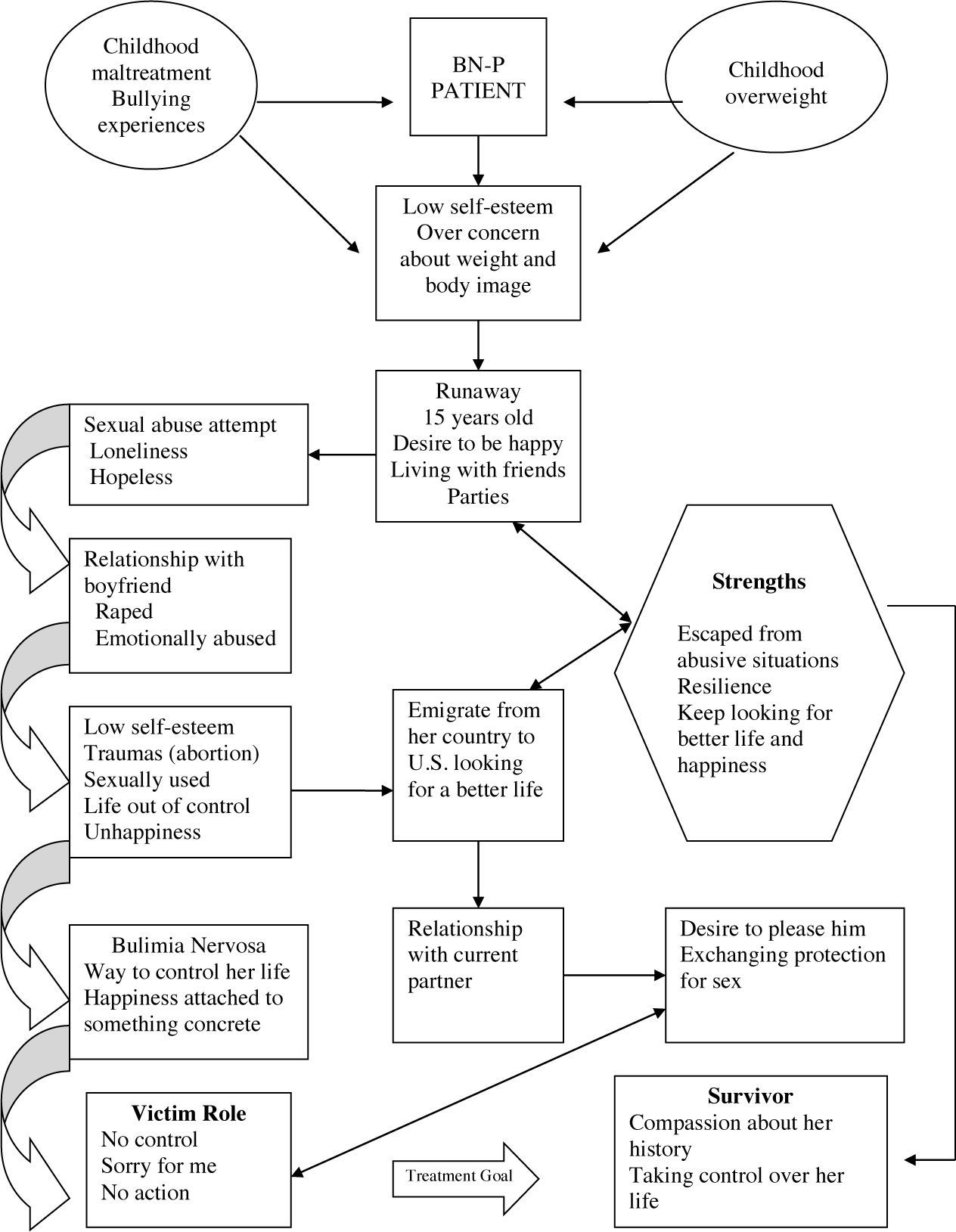

Near the end of Phase 1 (session 6), the therapist noted that the patient was challenged in understanding how all of the stressors and experiences in her life were related to her ED. Given the patient’s limited level of education and psychological sophistication, the therapist (M.L.R.) prepared a concrete diagram conceptualizing the evolution of the ED and incorporating the patient’s past experiences and current behaviors (See Figure 1). The diagram was used to help guide the patient’s understanding, as well as the therapeutic dialogue about low self-esteem, over concern about weight and shape, bulimic behaviors, and the perpetuation of the victim role. This concrete exercise assisted the patient in transitioning from a position of helplessness which was marked by the persistent question of “but why do I have an ED?” to a stance of greater understanding which seemed to enable her to participate actively in her own recovery rather than remaining a passive victim of an eating disorder. The validation of her strengths was a key element in her conceptualization and helping to build trust in her recovery process. For example, the therapist validated her strengths to make firm decisions to escape from abusive relationships and to move to another country with no resources; always looking for a better life. This conceptualization of her as a proactive, competent individual was important in order to challenge fatalism.

Couple-based sessionsThe couple-based intervention was scheduled to start at session 7 and was distributed across the three phases. Six couple-based sessions were included with a broad goal of providing the patient with support during the treatment process, along with specific emphases as noted below. Although the goal of the first couple session was intended to be a psychoeducational intervention about EDs, the patient began the session with a report of an incident of domestic violence in which the partner slapped the patient with an open hand during the past week regarding a disciplinary process with their children. According to the couple, this was the first violent incident that had ever occurred between them. The therapist changed course, conducted a safety assessment, and established a no violence commitment from both partners that was monitored throughout treatment. The therapist then identified crucial areas of intervention that the couple needed to address in order to free the patient to focus on recovery from BN. These family and couple issues included the disciplinary process with the children, couple communication, expression of affection and love, and intimacy issues (e.g., her perception of being used sexually by her partner). Both partners agreed with these goals, and couple sessions were planned every two weeks interspersed with individual sessions.

In the remaining couple sessions, one meeting was devoted to psychoeducation about EDs (e.g., what is an eating disorders, etiological factors, treatment and prognosis, how to support the patient in recovery); this focus was viewed as important so that the partner could understand the patient’s behaviors and how to support recovery. Four additional sessions were devoted to teaching and practicing couple communication skills (e.g., being an active listener, communicating in short and clear ideas, expressing needs and emotions). Communication is the single best predictor of long term couple functioning (Karney & Bradbury, 1995) and was seen as important for helping the couple address the patient’s BN as well as other couple concerns. Finally, one session focused on parenting skills (e.g., establishing family rules, developing consistent disciplinary methods, family structure at home).

Phase II establishing healthy eating patterns (Sessions 9-16)In this phase, all interventions were focused on establishing healthy eating patterns. During this phase, the frequency of binge eating and purging behaviors reduced to an average of three times per week from an initial level of one to three times per day. Three nutritional counseling sessions with a dietitian focused on developing a meal plan that considered affordable food that was preferred by the patient and her family and congruent with her ethnic background (e.g., beans and tortillas). An open discussion about the accessibility of specific food such as vegetables and fruits and the type of food that they usually consume was important in order to draft a tailored and realistic meal plan for the patient. Other interventions included mindful eating exercises, relaxation techniques, and continuing cognitive-behavioral approaches, incorporating decision-making processes to evaluate the pros and cons of having an eating disorder.

A turning point in therapy occurred in session 16 when the patient reported increased hair loss and became fearful of losing her hair secondary to BN. The patient showed body image issues associated with her EDs; however, a marked over-concern about her beauty was found (e.g., expressing jealousy because she thought her children were more beautiful than her). Her hair loss exacerbated her distress and contributed to a new cognitive distortion as the patient became frustrated with her perceived failure to change her behaviors. That is, she interpreted her hair loss as fatalism, and with an increased sense of helplessness, she began using laxatives in the form of “Tres Bailarinas,” a laxative tea. Her distorted belief that she would never overcome the bulimia (“ya para qué” or “what for”) became a central focus of treatment. Although such feelings of helplessness could emerge in EDs patients of any race or ethnicity, the fatalism in Latinos/as could contribute to a greater sense of inefficacy and a greater expectation of external control. Usually beliefs related to fatalism are presented in a rooted way and are more related to a collective cultural worldview. In addition to the cognitive behavioral techniques used to challenge distorted cognitions, it is important to create the awareness about the roots of their beliefs (e.g., religious, family patterns, cultural) in order to help the patient to acknowledge the nature of their beliefs and therefore overcome them. Being aware of this cultural belief in Latinos/as can help therapists who are not familiar with Latino culture contextualize distorted beliefs. Clarification and thorough discussion of this cognitive distortion and ongoing emphasis on the importance of recovery for both her and her children (pros and cons) led to a renewed commitment to recovery which continued during phase three.

Phase III relapse prevention (Sessions 17-26)In the final phase of the therapy, the patient began reporting several changes including improved interactions with her children (e.g., having fun and playing, consistent discipline) and with her partner (e.g., expressing affection, improved communication). The patient started taking active steps toward her own recovery (e.g., participating in a community exercise group, making notes to herself to remind her of positive thoughts). Interventions focused on assertive communication, control over eating when dining out, strategies for relapse prevention, and development of a termination plan. By session 20, the patient reported no binge or purge episodes and remained symptom free until the end of treatment (session 26). Also, substantial improvements were reported in depression symptoms (BDI=0) and other psychiatric symptomatology (SCL-36=55). On the family measures, changes were observed in the over-involvement subscale from FEICS (more family involvement) (Shields, Franks, Harp, McDaniel, & Campbell, 1992) and in the Familism Scale (Sabogal, Marín, & Otero-Sabogal,1987), which measures values and attitudes toward the family, focusing on identification and attachment between the family members, and feelings of family loyalty and reciprocity. Less acculturative stress was reported at the end of treatment compared with baseline. Areas of improvement included a sense of respect, willingness to seek help from government and health care agencies and realistic perceptions about how others treat her. Areas that were still sources of stress were language barriers in interactions with others and challenges in finding a job.

At the end of treatment, the patient enumerated future goals to learn English and return to school in order to assist her children in their school tasks. The validation of her strengths and her willingness to talk about her past traumas contributed to her recovery process. After completion of the treatment protocol, the patient was referred to a community mental health clinic to optimize her full recovery and prevent relapse.

DiscussionThis case represents a unique presentation of a monolingual, undocumented, uninsured, and poorly educated Latina woman eating disordered patient. This type of patient is rarely represented in typical clinical trials (Poker & Sharp, 2004), but with increasing numbers of undocumented monolingual individuals in the U.S., she may represent a population in need of intervention with unique challenges for the health care system.

Consistent with our previous experience with Latina women in Puerto Rico, this case showed the basic feasibility and the acceptability of CBT-BN in adult Latina women. Although no major changes in the core content of the CBT-BN intervention were necessary for this Latina woman patient, the integration of cultural values in the delivery of the intervention appeared to facilitate her engagement and retention into treatment. Familism is a strong value for Latinos/as and the inclusion of her partner and incorporation of parenting goals were factors that contributed to her treatment adherence. Her partner provided instrumental support by driving her to all appointments and looking after the children during sessions. On another level, her partner’s participation in couple sessions allowed for some basic but important improvements in their communication, parenting skills, and his understanding of EDs and the recovery process. This contributed to the patient’s experience that they were addressing her BN together as a couple rather than her attempting to address this confusing and overwhelming problem by herself which helped to elevate her sense of hope of recovery. Other factors that contributed to treatment adherence for both the patient and partner were the matching on ethnicity and language across the therapist, dietitian, and patient. This helped the patient feel heard and understood, thus, facilitating the therapeutic alliance and contributing to culturally sensitive interventions. Research on effects of racial/ ethnic matching of clients and therapists is not consistent; however, Latinos/as show strong preference for same ethnic therapists, especially when their level of acculturation is low (Cabral & Smith, 2011).

Symptom reduction was observed across the treatment protocol; however, the longer time course of change was not consistent with reports of early changes predicting good treatment outcome (Fernan-dez-Aranda et al., 2009; Le Grange, Peter, Ross, & Eunice, 2008). Consistent with our previous experience with the cultural adaptation in Puerto Rico, ED symptoms typically start showing improvement during the second phase of the treatment (9-16 sessions). It will be of value to determine whether the course of treatment differs in Latina women, and whether early response to treatment is similarly predictive of good outcome as has been observed in primarily Caucasian samples.

Three key lessons were gleaned from this formative case. First, consistent with other studies (Smyth, Heron, Wonderlich, Crosby, & Thompson, 2008; Ta-gay, Schlegl, & Senf, 2010), assessment of trauma in patients with EDs is relevant and necessary. Furthermore, interventions directly focusing on past traumas that interfere with treatment progress should be integrated into the broader treatment plan. Second, to ensure treatment adherence and medical compliance, the therapist’s role was not only as a psychologist but also as a care manager (e.g., calling to remind patient of appointments, coordinating and helping patient navigate the health care system, coordinating with other providers, exploring side effects of medication, etc.). This approach is consistent with a collaborative care model (combining evidence-based treatment and care management) and with the Latino cultural value of personalism. The collaborative model has been shown to overcome access barriers to mental health services in Latinos (Vera, Pérez-Pedrogo, Huertas, Reyes-Rabanillo, Juarbe at al., 2010). Personalism is a key cultural value in which Latinos promote close relationships, especially with those who demonstrate respect, caring, and well-meaning. The therapist, by adopting a care manager role, allowed the patient to experience a profound sense of validation (e.g., “You make me feel important”). Seemingly small efforts such as meeting the couple in the lobby to assist them with finding the clinic, or providing directions to parking personally rather than referring them to an assistant, are somewhat time-consuming, but valuable components of the intervention that are congruent with the value of personalism, promote a strong therapeutic relationship, and may assist with retention of Latinos in treatment. Third, plain words and concrete exercises are necessary for patients with low levels of education, and careful attention to nuanced differences in Spanish language concepts and words across different Latin cultures are important to ensure that all information and directions are understood.

As a single case, this report cannot be expected to generalize to other Latina women. In the absence of an evidence base, it illustrates the implementation of an evidence-based intervention and the flexible integration of culturally sensitive adaptations. The implementation of the intervention in a group of Latina women from diverse countries of origin is planned for the future phase of the project, which will then be well-positioned to address generalizability.

ConclusionThis case study represents the first step in the development of a treatment model for Latina women with eating disorders in the U.S. It demonstrates the challenges of providing an evidence-based intervention to a patient with multiple disadvantages (i.e., low education, no documentation, and a lack of health insurance). It also illustrates how adaptations such as including the partner, being flexible on topics addressed and scheduling, adhering to cultural values of personalism and familism, and providing culturally relevant interventions can lead to successful completion of a course of therapy and also facilitate ongoing interventions to ensure continued recovery. Consistent with a previous study (Ishikawa, Carde-mil, & Falmagne, 2010), this case demonstrates the integration of personal, family, and cultural factors in shaping the conceptualization of suffering and healing. The therapist’s alignment with the client’s world view, such as therapist multicultural competence, is a key factor in treatment outcomes (Cabral & Smith, 2011). This case provides an example of the cultural adaptation process of evidence-based intervention in Latinos/as, which is applicable to other mental health conditions.

This research has been supported by NIMH grant (K-23-MH087954) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The NIMH had no further role in the study design;in collection; analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. We express our gratitude to the patient and family who participated in this research. We are grateful to Dr. Millie Maxwell for her thoughtful comments on a previous draft of this manuscript.