The aim was to evaluate possible associations between media influence (internalization, pressure and information) on body satisfaction in a sample of Brazilian female undergraduate students. Sample consisted of female undergraduate from 37 institutions in Brazil who answered the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-SATAQ (n=2,414) and the Stunkard's Silhouettes Scale (n=2,402). A bivariate correlation among variables was performed, and also a covariance analysis with the SATAQ score and the body satisfaction categories. Linear multiple regression was done to evaluate the influence of variables in body dissatisfaction. Results show 64.4% of students desired to be smaller, 21.8% to be equal and 13.9% to be bigger than their actual figure. The group of students who desired to be smaller had the greatest SATAQ total and all the subscales scores. According with regression analyses, the body dissatisfaction increased 0.22 for each more Body Mass Index point; 0.02 for each more unit in SATAQ Internalization-General subscale; 0.03 for each more unit in SATAQ Pressure subscale. It was concluded that media influence and body dissatisfaction were related; in addition, media Internalization and Pressure predicted body dissatisfaction for this sample. The knowledge provide by these results is important for prevention strategies.

El objetivo fue evaluar las posibles asociaciones entre la influencia de los medios de comunicación (internalización, presión e información), con relación a la satisfacción corporal en estudiantes brasileñas. La muestra incluyó mujeres universitarias de 37 instituciones de Brasil que respondieron el Cuestionario de Actitudes Socioculturales hacia la Apariencia-SATAQ (n=2,414) y la Escala de Siluetas de Stunkard (n=2,402). Se realizó un análisis de correlación bivariada entre las variables, y un análisis de covarianza entre las puntuaciones del SATAQ y las categorías de satisfacción corporal. La regresión linear evaluó la influencia de las variables en la insatisfacción corporal. Los resultados muestran que 64.4% de las estudiantes deseaban estar más delgadas; 21,8% igual y 13.9% deseaban una talla mayor que la actual. El grupo que deseaba estar más delgado, presentó puntuaciones más altas en el SATAQ y en sus subescalas. El análisis de regresión evidenció que la insatisfacción corporal aumentaba 0.22 para cada unidad del Índice de Masa Corporal; 0.02 para cada unidad en la subescala Internalización-General del SATAQ y 0.03 para cada unidad en la subescala Presión del SATAQ. Se concluye que la influencia de los medios de comunicación puede relacionarse con la insatisfacción corporal, además, la Internalización y la Presión de los medios de comunicación predijeron la insatisfacción corporal. Este conocimiento es importante para la planeación de estrategias de prevención de los trastornos de la alimentación.

Evidence from literature demonstrate that media could be an important bias in weight and eating problems, from disordered eating to clinical eating disorders. It's also well known that a frequent exposure to thin bodies, from media messages e.g. magazines and TV, could lead to body dissatisfaction. This influence is more frequent among adolescent and young women, in developing and developed countries (Cafri, Yamamiya, Brannick, & Thompson 2005; Harrison & Cantor, 1997; Stice, Schupak-Neuberg, Shaw, & Stein, 1994).

Studies about emergence of body image problems and risk factors for body dissatisfaction have shown that exposure to an idealized body – and – acceptance or internalization of this ideal contribute to the development of body dissatisfaction (Cafri, et al., 2005; Durkin, Paxton, & Sorbello, 2007; Jones, Vigfusdottir, & Lee, 2004; Monro & Huon, 2005).

A sociocultural theoretical model propose that societal standards for an unreal beauty stress the importance of thinness as well as other standards of prettiness, which are difficult to reach (Tsai, Curbow, & Heinberg, 2003). This model emphasizes that societal standard for thinness is omnipresent, and unfortunately, unachievable for most women. Indeed, although overweight and obesity has been increasing over recent years, evidence suggests that the ideal has become progressively thinner (Spypeck, Gray, & Ahrens, 2004).

Three constructs related to perceived influence of social and cultural factors have received particular attention concerning their relationship with body image attitudes: awareness of a thin ideal in the media, internalization of thin ideal and perceived pressures to be thin (Durkin & Paxton, 2002; Stice, 2002; Thompson & Stice, 2001). Awareness of the thin ideal has been defined as the simple knowledge that a standard exists, as opposed to the internalization of the thin ideal, which is a profound incorporation or acceptance of the value, to the point that the ideal affects one's attitudes – body image – or personal behavior – e.g. dieting. Perceived pressures to be thin, is related to pressure that comes from family, friends, dating partners, and media (Cafri, et al., 2005; Heinberg, Thompson, & Stormer, 1995; Thompson & Stice, 2001). In the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Scale (SATAQ), the constructs evaluated to measure of societal influences are internalization (general and athlete), pressure and information (a form of evaluation of the awareness); an awareness subscale was first proposed for this instrument but dropped from the final version.

Research has demonstrated that perceived pressure to be thin and internalization may be a causal risk factor for the onset of eating and shape-related disturbances and may mediate the relationship between sociocultural influences and body dissatisfaction (Thompson & Stice, 2001; Calogero, Davis, & Thompson, 2004).

In Brazil, the magnitude of body image disturbances is not well explored; most studies are local and evaluated small samples (Bosi, Uchimura, & Raggio, 2009; Moreira, et al, 2005). Even more the media influence is rarely evaluated (Alvarenga, Dunker, Philippi, & Scagliusi, 2010; Dunker, Fernandes, & Carreira Filho, 2009).

Considering the importance of its variables for eating and body disturbances and the lack of information about their association in the Brazilian scenario, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the possible association between media influence – regarding information, pressure to be thin and internalization – and body dissatisfaction for a sample of Brazilian female undergraduate students.

MethodsDesign & SettingA sample of undergraduate female students was defined to evaluate media influence, body dissatisfaction, eating attitudes and eating disorders risk behavior in a transversal study in all regions of Brazil (Alvarenga, Scagliusi, & Philippi, 2011). It was a broad study with this sample; and for the present study we will be presenting data regarding media influence and body dissatisfaction.

In order to achieve a sample of young female subjects a partnership with public and private education institutions was sought. Formal invitations for partnership were sent through e-mail to 130 higher education institutions that had undergraduate courses in nutrition and were listed in the National Nutrition Board. Study questionnaires were forwarded to coordinators at the institutions that agreed to participate. A total of 37 (28.5%) responded and signed the research partnership agreement required.

Sample

The sample size was determined as described previously (Alvarenga, et al., 2011). Subjects were selected from nursing, psychology speech therapy, physical therapy, pharmacy and biomedicine majors, which were available in most institutions. Inclusion criteria were a) students attending the first and second year, b) being females, c) aged over 18 and under 50, d) to sign an informed consent agreeing to participate. Exclusion criteria were a) to be a dietitian or attending undergraduate studies in nutrition, b) being pregnant, c) to inform a health condition that could have an impact in eating attitudes (such as an eating disorder). Dietitians and/or those attending undergraduate studies in nutrition were not included because studies have showed that nutrition students have different eating behaviors (Alvarenga, et al., 2011).

Local coordinators received specific instructions about the questionnaires administration. Following the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the questionnaires were then auto completed in the classroom and respondents were required to provide information such as age, income, education of family head and self-reported body weight and height.

InstrumentsMedia influence was evaluated using the “Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Scale” (SATAQ). The third version of this instrument (SATAQ-3) used in this study was done after some revisions and was developed with a sample of undergrad female students (Thompson, Berg, Roehrig, Guarda, & Heinber, 2004). It has 30 Likert questions (Cronbach's Alpha .94), and 4 subscales: 1- Internalization general (9 questions and Alpha .92); 2-Internalization athletic (5 questions and Alpha .89), both assess an incorporation of appearance standards promoted by the media into one's self-identity to the point that an individual desires or strives to meet the ideals; 3-Pressure (7 questions and Alpha .94), contains items that index a subjective sense of feeling pressure from exposure to media images and messages to modify one's appearance; and 4-Information (9 questions and Alpha .94), acknowledgment that information regarding appearance standards is available from media sources. The answers options are: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree and strongly disagree (5, 4, 3, 2 e 1 points respectively). The Portuguese version was prepared with the author's agreement after a translation and back translation process at time of the study (Alvarenga, Dunker, et al., 2010) and it had appropriate internal consistency in this evaluation with undergrad students (Cronbach's Alpha .91).

The body dissatisfaction was evaluated using Stunkard's Silhouettes Scale (Stunkard, Sorensen, & Schlusinger, 1983) which evaluates: body size and shape perception, ideal shape and body dissatisfaction. The scale has nine figures (numbered from 0 to 8), from the thinner to a heavier one. The respondent chose one figure that represents his actual body (“I figure”) and the desired figure (“Desired figure”). Desire-score was obtained from the difference between the perception and desired (I figure minus Desired figure), in which positive values mean a wish to be smaller, and negative values a wish to be bigger.

The scale was adapted for females in Brazil and it was found it is a valid measure of body image (Scagliusi, et al., 2006). An appropriate general validity for the Silhouettes Scale was found and proper test-retest reliability (r=.71) was found latter evaluating women (Thompson & Altabe, 1991).

AnalysisStatistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 17.0 (Statistical Package for Social Science Inc., Chicago, Illinois USA). The significance level adopted was .05. Variables distribution normality was tested by means of Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

The number of the figure chosen as Actual, Desired and Desire-score at Stunkard's Silhouettes scale was analyzed (frequency of each number chosen from 0 to 8; and difference from actual and desired). The number of students (and frequency) that chose a figure equal, smaller and bigger than their actual one was also evaluated. A correlation between SATAQ scores and those dissatisfied with body image (analyzed as numeric variable, using Desire-score values) was performed using Person coefficients (also age and BMI).

A covariance analysis was performed with the SATAQ score and the body satisfaction categories: 1) students that desire to be equal than their actual figure, 2) students that desire to be smaller and 3) students that desire to be bigger than their actual figure. Covariables age, Body Mass Index – BMI (kg/m2), income and education of family head was used to verify influence in the results. Pairwise comparisons were performed using Bonferroni's post-hoc test.

A linear multiple regression analysis with Stepwise process to select variables was performed to evaluate the influence of media (SATAQ's subscales scores), age and BMI in the body dissatisfaction (evaluated as Desire-score, that means body dissatisfaction when value is different than zero).

All students signed a free informed consent form. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Public Health School – University of São Paulo (COEP 211/06 protocol 1351).

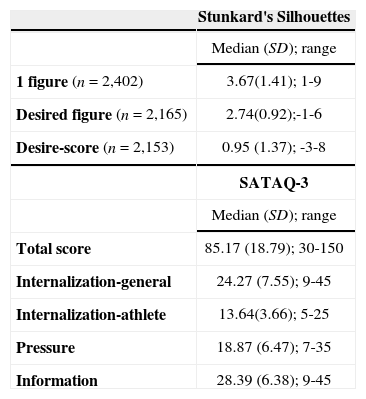

ResultsThe number of students that properly answered the Stunkard's Silhouettes were 2,402; and 2,414 properly answered the SATAQ-3. The scores at these instruments are shown at Table 1. The students were 23.5 years old (SD=6.1) and had an average BMI of 22.0 Kg/m2 (SD=3.5).

Figures chosen as actual and desired and desire-score at Stunkard's Silhouettes and SATAQ-3 (n=2414) total and subscales scores of Brazilian undergraduate female students.

| Stunkard's Silhouettes | |

| Median (SD); range | |

| 1 figure (n=2,402) | 3.67(1.41); 1-9 |

| Desired figure (n=2,165) | 2.74(0.92);-1-6 |

| Desire-score (n=2,153) | 0.95 (1.37); -3-8 |

| SATAQ-3 | |

| Median (SD); range | |

| Total score | 85.17 (18.79); 30-150 |

| Internalization-general | 24.27 (7.55); 9-45 |

| Internalization-athlete | 13.64(3.66); 5-25 |

| Pressure | 18.87 (6.47); 7-35 |

| Information | 28.39 (6.38); 9-45 |

Note: SATAQ-3 = Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire (3rd revision). The total valid n for each category is indicated since not all students reported all information.

The students chose in average Figure 4 as representative of their actual body (“I figure”), the figures more commonly chosen were number 4 (29.9%), 3 (21.3%) and 2 (19.8%). In average they desired as a figure one number smaller than their actual, the figures more commonly chosen as “desired” were number 3 (38.4%) and 2 (33.3%).

The range of Desire-score varied from 3 bigger figures and 8 smaller figures (−3 to +8). It was found that 64.4% of students desired to be smaller, 21.8% desired to be equal and 13.9% to be bigger than their actual figure.

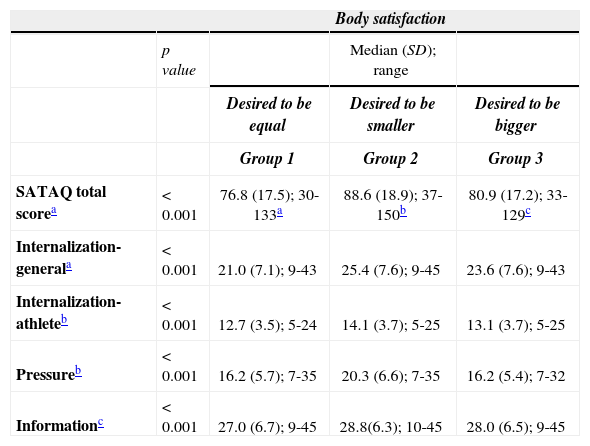

The results on SATAQ-3 total and subscales scores according with this classification (desire to be equal, smaller or bigger than student's actual figure) are shown at Table 2.

Brazilian Female Undergraduate Students SATAQ-3 Total and Subscales Score According with the Desire to Be Equal (n=456), Smaller (n=1,350) or Bigger (n=288) than Actual Figure – Evaluated Using Stunkard's Silhouettes.

| Body satisfaction | ||||

| p value | Median (SD); range | |||

| Desired to be equal | Desired to be smaller | Desired to be bigger | ||

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | ||

| SATAQ total scorea | < 0.001 | 76.8 (17.5); 30-133a | 88.6 (18.9); 37-150b | 80.9 (17.2); 33-129c |

| Internalization-generala | < 0.001 | 21.0 (7.1); 9-43 | 25.4 (7.6); 9-45 | 23.6 (7.6); 9-43 |

| Internalization-athleteb | < 0.001 | 12.7 (3.5); 5-24 | 14.1 (3.7); 5-25 | 13.1 (3.7); 5-25 |

| Pressureb | < 0.001 | 16.2 (5.7); 7-35 | 20.3 (6.6); 7-35 | 16.2 (5.4); 7-32 |

| Informationc | < 0.001 | 27.0 (6.7); 9-45 | 28.8(6.3); 10-45 | 28.0 (6.5); 9-45 |

Note: SATAQ-3 = Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire (3rd revision).

The impact of covariables was evaluated and after adjustments it was found that the group of students that desired to be smaller (group 2) had the greatest SATAQ – total an all the subscales score. This group scores were significantly different from the other groups for all subscales except for Information – where those who want to be smaller and bigger were not different. For the Information subscale any variable had influence in the results, and the analysis was performed with ANOVA.

Students who wanted to be bigger (group 3) were not different from those wanting to be equal regarding Internalization-athlete, Information and Pressure. This group scores were significantly different from “equal group” just for SATAQ total score and Internalization-General.

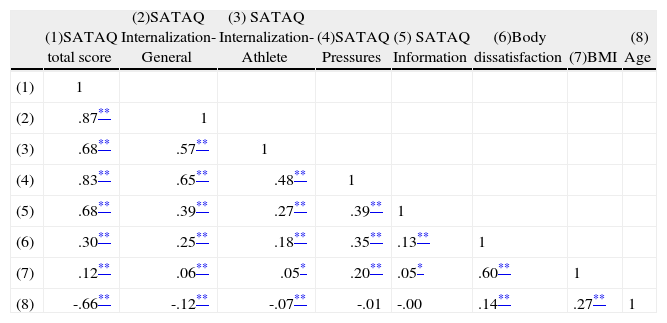

The bivariate correlation showed that BMI was strongly correlated with body dissatisfaction (.60); and age was strongly negatively correlated (.66) with SATAQ total score (Table 3). It was found that body dissatisfaction had a moderate correlation with SATAQ total (.30) and Pressure (.35) scores.

Inter-item Correlations Between Media Influence, Body Satisfaction, Weight Status and Age.

| (1)SATAQ total score | (2)SATAQ Internalization-General | (3) SATAQ Internalization-Athlete | (4)SATAQ Pressures | (5) SATAQ Information | (6)Body dissatisfaction | (7)BMI | (8) Age | |

| (1) | 1 | |||||||

| (2) | .87** | 1 | ||||||

| (3) | .68** | .57** | 1 | |||||

| (4) | .83** | .65** | .48** | 1 | ||||

| (5) | .68** | .39** | .27** | .39** | 1 | |||

| (6) | .30** | .25** | .18** | .35** | .13** | 1 | ||

| (7) | .12** | .06** | .05* | .20** | .05* | .60** | 1 | |

| (8) | -.66** | -.12** | -.07** | -.01 | -.00 | .14** | .27** | 1 |

Note: SATAQ-3 = Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire (3rd revision); BMI = Body Mass Index.

Body dissatisfaction evaluated as Desire-score (actual body figure minus desired body figure) on Stunkard's Silhouettes.

Sample size for SATAQ-3, BMI and age = 2,414; and for Body dissatisfaction = 2,402.

For the regression analysis all variables were considered in the first model. SATAQ total score was not evaluated in this model because it had high correlation with all subscales (see Table 3). In the sequence the significant ones for the model (that explain body dissatisfaction) was included. The model was well adjusted to explain the independent variables that elucidate the increase in body dissatisfaction (R2=.606; p<0.001).

Fixing the other variables, it was found, that in relation to the body dissatisfaction: for each one more year old, the Desire-score (that is, the dissatisfaction) increased .015; for each more BMI point, the Desire-score increased .221; for each more unit in SATAQ subscale 1 (Internalization-general), the Desire-score increased .022; and for each more unit in SATAQ subscale 3 (Pressure), the Desire-score increased .032. Could be inferred that BMI was the strongest predictor of body dissatisfaction – followed by the scores of subscales Pressure and Internalization-general.

DiscussionThis study evaluated the association of media influence on body dissatisfaction among Brazilian female students and found there was a relation between these factors, such as, those more influenced by media desired to be smaller than their actual body figure – and could be considered more dissatisfied.

First of all, it was found that the magnitude of body dissatisfaction was expressive and besides that, even normal weight students desired to be smaller (Alvarenga, Philippi, Lourenço, Sato, & Scagliusi, 2010); this result attest the normative discontent of younger women nowadays. Regarding the media influence, it was found that the scores on SATAQ were higher than other population around the world (Alvarenga, Dunker, et al., 2010), also that the younger and overweight students were the most influenced by media.

Results showed that media influence was higher for the students that desired to be smaller than their actual body, and it was different for the ones that desired to be equal (the “satisfied” ones) for general media influence and all subscales on SATAQ. Besides that, the “satisfied” ones were also different from those who wanted to be bigger for general media influence and for Internalization-general – showing that media influences most all who desired to be different (smaller or bigger), or vice versa.

On other hand, for Internalization-athlete, Information and Pressure the influence was not different for the “satisfied” and those wanted to be bigger – just from those who desired a smaller body. This result proved that the pressure of media is truly concentrated on losing weight message.

At last, for Information the ones who wanted to be smaller and bigger were similar – difference was found just between the “satisfied” compared with those who desired a smaller body. Therefore those who desire to be smaller or bigger are influenced in the same level for information available from media sources regarding appearance standards, but those who wanted to be smaller are more influenced than individuals satisfied.

Correlation between BMI and body dissatisfaction is known elsewhere and is related to the result of more media pressure for those with higher BMI in this sample (Alvarenga, Philippi et al., 2010). BMI was the strongest predictor of body dissatisfaction for this group of young women. Even considering that weight and height were self-reported in the present study the result is valid and reliable since a meta-analysis concluded that self-reported measures are good estimates of actual ones (Bowman & De Lucia, 1992), and Brazilian studies found high consistency between self-reported and measured data for epidemiological studies (Fonseca, Faerstein, Chor, & Lopes, 2004; Peixoto, Benicio, & Veiga, 2006).

It is known that overweight is highly stigmatized, and is easily observed that media portraits the weight loss searches and the pursuit of the “ideal body” as popular themes. This reality predisposes to increased worry about weight, and use of diets and compensatory methods – which helps to understand why those more far from the cultural “ideal body” are more unsatisfied. Regarding age, the result of negative correlation with total media influence makes sense when it is known that older students had less chance to be influenced by media (Alvarenga, Dunker, et al., 2010). The younger seems to accept and adhere more to non realist aesthetic ideals (Internalization) and this result is similar with other studies (Groez, Levine, & Murner, 2002; Madanat, Hawks, & Brown, 2006).

The relation of SATAQ's subscales and body image disturbances was described previously (Cafri et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2004). In the present study all SATAQ's scores was found to be correlated with body dissatisfaction; and specifically the Internalization-general and Pressure predicted the dissatisfaction. This result is coherent with the fact that Internalization subscale significantly predicts body image disturbance and eating disordered behavior (Heinberg, et al., 1995).

Besides the relation with body image, it is also affirmed that SATAQ's subscales have strong relation with weight control practices (Cafri et al., 2005). In this line of thought, the media strongly influences the individual tendency to adopt disordered eating attitudes and behaviors (O'Riordan & Zamboanga, 2008).

Focusing specifically on media internalization, it is affirmed that it could be a casual risk factor for eating and weight problems (Thompson & Stice, 2001). A metaanalytic review across 33 studies, found large to medium effect size for Internalization of thin ideal on body image (Cafri, et al., 2005); and a direct effect of media exposure in eating disorders symptoms of college women was found – with the internalization of the stereotyped ideal body having a mediation role in this mechanism (Stice, et al., 1994). Perhaps most importantly, was affirmed that it is possible to modify internalization and this change appears to be related to alteration in levels of body dissatisfaction and eating disturbance (Stice & Hoffman, 2004).

The use of the Brazilian version of SATAQ must be considered as a limitation of this study since the instrument was just translated and not validated for the Brazilian scenario at that time – nowadays a semantic equivalence and internal consistency study was done (Amaral, Cordás, Conti, & Ferreira, 2011). Nevertheless the internal consistency obtained in this evaluation was adequate (total score= 0.91; subscale 1 Internalization-general = 0.86; subscale 2 Internalization-athlete = 0.68; subscale 3 Pressure = 0.87; subscale 4 Information = 0.77) and similar to the original study of SATAQ's development (Thompson et al., 2004). In addition, SATAQ has been used in different countries for body image and eating disorders studies, presenting good internal consistency and proper convergent validity in clinical and non clinical samples (Cafri et al., 2005).

It is essential to identify risk factors for body dissatisfaction and disordered eating since mass media has a crucial role in the formation and reflection of public opinion, and its claimed that media internalization could be the causal risk factor for the beginning of eating and weight issues (Thompson & Stice, 2001). So, the present results and discussion could add to this issue in Brazilian – and others countries – scenario.

Body dissatisfaction is associated with depressive symptoms, stress, low self-esteem, eating restraint and physical activity avoidance (Anton, Perri, & Riley, 2000; Johnson & Wardle, 2005; Markey & Markey, 2005). Body image disturbances – that are related with media influence – are well known factors for the development of clinical and sub clinical eating disturbances; and body dissatisfaction strongly influences the diet practices and other restrictive strategies (van den Berg, Thompson, Obremski-Brandon, & Coovert, 2002; Thompson & Smolak, 2001). Understanding the mechanism involved in the media exposure's influence is critical in the development and implantation of effective prevention programs (Calado, Lameiras, Sepulveda, Rodríguez, & Carrera, 2010; Thompson, et al., 2004).

Media literacy training could represent a promising approach in eating and body disturbances prevention; it is based in cognitive behavioral theory and aims to decrease risk factors for disordered eating and body hatred using interactive activities to help the adoption of a critical view about media, proposing alternatives for the cultural ideals presented (Wilksch, Tiggemann, & Wade, 2006).

ConclusionThere was a relation between media influence and body dissatisfaction in this sample of Brazilian undergrad students: those more influenced by media desired to be smaller than their actual body figure, and considered more dissatisfied. BMI was the strongest predictor of body dissatisfaction and specifically the Internalization-general and Pressure subscales of SATAQ predicted dissatisfaction.

Since body dissatisfaction and media influence are important factors for the development of clinical and sub clinical eating disturbances, a better knowledge of the system involved in the media exposure's influence is decisive for development and implantation of effective disordered eating prevention programs.

Research support: FAPESP – Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São (process 06/56850-9).

Authors would like to thank the significant collaboration of nutrition courses coordinators and their partners in the data collection at institutions which participated in the research.