To establish a correlation amongst clinical, radiographic and histological characteristics of dental apical lesions at the time of diagnosis.

Material and methodsA descriptive study which undertook to establish comparison of clinical and radiographic characteristics with histopathological study of lesions. Included in the study were samples of individuals which had been previously diagnosed with periapical disease processes; samples were harvested from apicoectomies and dental extractions. In order to achieve histological diagnosis, a pathologist routinely processed and assessed all specimens.

Results50% of all samples were diagnosed as apical periodontitis, followed by periapical cysts (28.5%). An association of (p = 0.01) was found when correlating clinical characteristics such as sensitivity to percussion and spontaneous pain. The same situation arose when relating vertical bone loss to dental mobility (p = 0.023), and dental mobility with affected tooth (p = 0.036), nevertheless, no association was found with correlation of patient's symptomatic status, such as spontaneous pain, and type of predominant inflammatory infiltrate in the lesions (p = 1.4), nevertheless, association was found with the secondary infiltrate type existing in them (p = 0.057). Dental mobility was taken as diagnostic marker for granuloma and periapical cyst (p = 0.025).

ConclusionsCertain clinical markers were found with the ability to predict histological manifestation of the lesions, such as dental mobility for granuloma and periapical cyst cases. Nevertheless, exact prediction of each one of the diseases is still difficult to obtain, this is due to the lesion's dynamics and the scarce correlation existing among clinical and radiographic characteristics with the histological description of the lesions.

Establecer la correlación entre las características clínicas, radiográficas e histológicas de lesiones apicales dentales al momento de su diagnóstico.

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo en el que se realizó la comparación de las características clínico-radiográficas con el estudio histopatológico de las lesiones. Se incluyeron muestras de individuos que fueron diagnosticados con procesos de patología periapical, obtenidas a través de apicectomías y extracciones dentales. Los cortes fueron procesados rutinariamente y evaluados por patólogo para su diagnóstico histológico.

ResultadosEl 50% de las muestras fue diagnosticado como periodontitis apical, seguido por quistes periapicales (28.5%). Al correlacionar entre sí características clínicas como sensibilidad a la percusión y dolor espontáneo hubo asociación (p = 0.01). Igualmente, al relacionar la pérdida ósea vertical con movilidad dental (p = 0.023) y ésta con el órgano dentario afectado (p = 0.036). Sin embargo, no mostró asociación, la correlación entre el estado sintomático del paciente como dolor espontáneo y el tipo de infiltrado inflamatorio predominante en las lesiones (p = 1.4); pero sí la hubo, con el tipo de infiltrado secundario que existía en ellas (p = 0.057). La movilidad dental se mostró como un marcador diagnóstico para granuloma y quiste periapical (p = 0.025).

ConclusionesSe hallaron ciertos marcadores clínicos capaces de predecir la presentación histológica de las lesiones, como la movilidad dental para granuloma y quiste periapical. Sin embargo, la predicción exacta de cada una de las patologías aún se hace difícil, debido a la misma dinámica de las lesiones y a la poca correlación que existe entre las características clínico-radiográficas con la descripción histológica de las lesiones.

Apical lesions are a set of chronic inflammatory processes generally caused by microorganisms or their by-products. They reside in or invade the periapical tissue located at the root canal, and they manifest due to the defense response of the host to the microbial stimulus in the root canal system.1,2 It has been mentioned that its pathogenesis begins with the development of soft tissues’ peri-radicular destruction after bacterial infection of the dental pulp, so that components of bacteria’ s cell wall react to monocytes, macrophages, fibroblasts and other cells of the immune system. This causes production of pro-inflammatory cytokines responsible for tissue destruction an degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components, including collagen and proteoglycans, and resulting in the resorption of hard tissues as well as destruction of other periapical tissues.2,3

According to the American Association of Endodontics, from the histopathological point of view, the first changes produced at periapical level are characterized by hyperemia, vascular congestion, periodontal ligament edema and neutrophil extravasation, which are attracted to the area through chemotaxis, initially induced by tissue lesion, bacterial products, lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and C5 factor of the complement.1–5

Among factors associated to the origins of this alteration we can count mechanical type factors such as trauma and instrument-caused lesions and chemical factors such as tissue irritation caused by endodontic materials. It is worth noting that these mechanisms can trigger a mild or severe response of the host organism, which might be accompanied by clinical symptoms such as pain upon pressure on the tooth and in some cases tooth elevation.6,7

It has been reported that this condition mostly affects patients in their third decade of life,7 nevertheless and in spite of the fact that periapical disease has been treated for years, it has been reported that 79% of all endodontically treated teeth present a lesion of some kind. This figure is influenced by the high error rate in diagnosis and wrong treatment decisions, as well as by the high percentage of cases, which, in spite of receiving endodontic treatment could not culminate in a resolution of the condition.8,9 Jaramillo, conducted a study of 47 teeth in 2009. He reported that 87.8% of studied teeth were poorly filled, bearing in mind ideal apical seal and length. This would partly justify the high prevalence of lesions found in the population.8 This last factor, along with the existence of other factors which hinder total tissue repair such as pulp necrosis and proteolytic activity, prevent root physiological growth as well as permanent apical closure.9

With respect to clinical evaluation, Kuc et al10 reported that only 59% of clinically diagnosed cases were consistent with the histopathology, they additionally informed that about 30% of all diagnoses emitted were completely wrong.10 Radiographic evaluation was considered the most widely used method to detect periapical lesions, nevertheless, this assessment offers images in two dimensions of tridimensional structures, thus, accuracy regarding lesion size, extension and location9 might be lost along the way. Accurate clinical and radiographic diagnosis guarantees suitable endodontic treatment of teeth presenting pulp and/or periodontal lesions, without overlooking suitable crown filling or rehabilitation, therefore, this factor becomes vital.

Bearing all the aforementioned in mind, many authors suggest performing histological studies in those cases where apical lesions do not disappear, so as to determine their relationship with the clinical aspects.11,12 Nevertheless, use of histopathology, the diagnosis gold standard, is presently subject to controversy since there is no universal protocol for examining all soft tissue recovered from extracted teeth or apical surgeries.13 Walton mentioned that histological examination might be important in cases where the lesion does not disappear and implies a severe health risk for the patient, but he does not support routine use of the analysis, based on cost/benefit reasons for the patient.11–13

The aim of the present study was to determine relationship between clinical, radiographic and histopathological evaluation of dental apical lesions at the moment of their diagnosis.

MATERIAL AND METHODSThe present was a comparative, descriptive study where samples of apical lesions were taken through extraction procedures and apicoestomies of subjects treated at the undergraduate and graduate clinics of the School of Dentistry, University of Cartagena, in the period comprised between 2014-2015. Teeth presenting apical lesions of endodontic origin and soft tissue harvested by means of their curettage were included in the project.

The following were excluded: lesions not associated to endodontic condition and radiographs in poor condition (due to errors incurred when taking or developing them). In order to be suitably preserved, samples were fixated in 10% buffered formalin, later they were bathed in paraffin and histological cuts of X microns were performed, to be then examined under a light microscope.

Clinical analysisPatients were initially subjected to a clinical assessment which took into account the following variables:

Tooth mobility: this was determined according to movement exhibited by the affected tooth in horizontal or axial direction, it was classified into grade I (0.2-1mm horizontal mobility), grade II (> 1mm horizontal mobility) and grade III (crown mobility in axial direction). Presence of fistula: its assessment was conducted by means of fistulography (fistulogram) procedures as well as clinical observation. Crown fracture: was classified according to Andreasen et al which was established bearing in mind the loss of tooth substance which compromised tooth structures (enamel, dentin and pulp chamber).14

There was spontaneous pain assessed through patient history which considered type of pain as well as whether it was spontaneous in which case it would be classified as present or absent.15,16

The following variables were equally taken into account: sensitivity to percussion and facial tumefaction for assessment, inflammation of soft or facial tissues was determined by the presence of blush, pain, heat and deformation of patients’ tissues. Sensitivity to percussion was conducted with a metallic instrument by means of a vertical and horizontal soft tap into the tooth's crown.15

Type of most affected tooth: was obtained based on occurrence per type of tooth (incisor, canine, premolar or molar); age group: based on age classifying patients by age ranges; patient gender: patients were classified according to gender.6

Radiographic analysisOsorio's study7 conducted in 2008 was taken into account to conduct radiographic analysis. This analysis assessed the following variables:

Size of lesion: for size calculation, the following mathematical formula was for surface calculation used: base or diameter multiplied by height or length and then divided into two, using the area of lamina dura continuity loss as reference poin. In this sense, a lesion was considered to be large when measuring 7mm or more, and small when measuring 6mm or less.7

Lesion location: this was assessed bearing in mind the cervical, middle and apical and apical-medium third of each affected tooth.

Periodontal ligament space widening: the space was horizontally measured in mm from the root surface up to the lamina dura.

Lamina dura: was vertically measured following the radio-opaque continuity observed, from the bone crest to the point where the periapical lesion became visible.

Bone loss: was vertically evaluated, measuring from the cervical third up to the apex of the tooth and was classified according to loss percentage into : incipient (0-22%), moderate (21-50%) and severe(≥ 51%).7–9

All X-rays were digitalized with X-ray reader WXR700 X-Ray Film Reader (KAB Dental Equipment Inc, Sterling Heights MI, USA)I to achieve standardization and greater precision when measuring all variables. This receptor was connected to a portable computer visualization device (COMPAQ mini 102_hp INC). After this, all measurements were conducted with the program VixWin Platinum (version 3.3, Gendex INC, USA)II. All X-rays had been previously gauged taking into account the real size of the tooth so as to avoid any type of distortion which might affect the research.

Histopathological analysisA macroscopic description with individual photographic documentation on high visual contrast of all obtained samples was initially undertaken; a millimetric rule was used to document lesion size. Photographs were taken with a Kodak® digital camera model EasyShare M531, with 14 megapixels and 3x optic spherical lens. Detailed description included the following aspects: shape, color, size, consistency, association to dental tissue or lack of it as well as lesion content. In order to emit macroscopic diagnosis, variables studied by Kuc and Gbolahan in 2000 and 2009 respectively were taken into account. These variables were: cell predominance, type of epithelium and inflammatory infiltrate (predominant and secondary), presence of wall, cavity and blood vessels.10–16 Finally, in order to reach final diagnosis, a correlation between macroscopic and microscopic study was established with the help of radiographic and clinical analysis.

Statistical analysisData were initially tabulated in a Excel version 2010 table for descriptive analysis, determining central tendency and dispersion measurements.

At a later stage the χ2 test was applied in order to establish correlation between qualitative variables of each of the analyses.

Finally, in order to fixate correlation between quantitative variables, the Shapiro Wilk test was first applied in order to determine data distribution or normalcy. Variables with normal distribution and same variables were correlated with the Pearson correlation test. Spearmen correlation was used to determine association in cases where no normalcy was found.

Ethical considerationsIn order to take samples, all patients were informed of the purpose and scope of the research, and detailed explanation was provided of all risks and benefits. Patients were requested to sign an informed consent form, stating their voluntary and autonomous participation in the study, as stated by the Belmont report and the Helsinki Declaration.17,18 The project was ruled by Resolution 008430 (1993) of the Social Protection Ministry of the Republic of Colombia, which classifies research with maximum-minimum risk for the patient. The project additionally counted with approval of the Ethics Committee of the University of Cartagena.

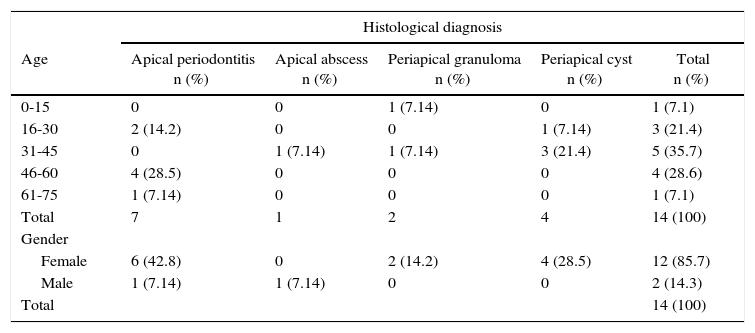

RESULTSSixteen samples were examined. Four of them were rejected due to lack of full data or suitable X-rays. Each one of the samples was associated to clinical and radiographic evaluation pertaining to each case. The group encompassing age range 35-45 years exhibited 35.7% of all analyzed samples; 86.7% were females (Table I).

Sample characteristics according to socio-demographic variables and final histological diagnosis.

| Histological diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Apical periodontitis n (%) | Apical abscess n (%) | Periapical granuloma n (%) | Periapical cyst n (%) | Total n (%) |

| 0-15 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.14) | 0 | 1 (7.1) |

| 16-30 | 2 (14.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.14) | 3 (21.4) |

| 31-45 | 0 | 1 (7.14) | 1 (7.14) | 3 (21.4) | 5 (35.7) |

| 46-60 | 4 (28.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (28.6) |

| 61-75 | 1 (7.14) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.1) |

| Total | 7 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 14 (100) |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 6 (42.8) | 0 | 2 (14.2) | 4 (28.5) | 12 (85.7) |

| Male | 1 (7.14) | 1 (7.14) | 0 | 0 | 2 (14.3) |

| Total | 14 (100) | ||||

It could be observed that apical disease most prevalent in this research were apical periodontitis (50%) and periapical cyst (28.5%). No association was found when correlating diagnosis with social and demographic variables.

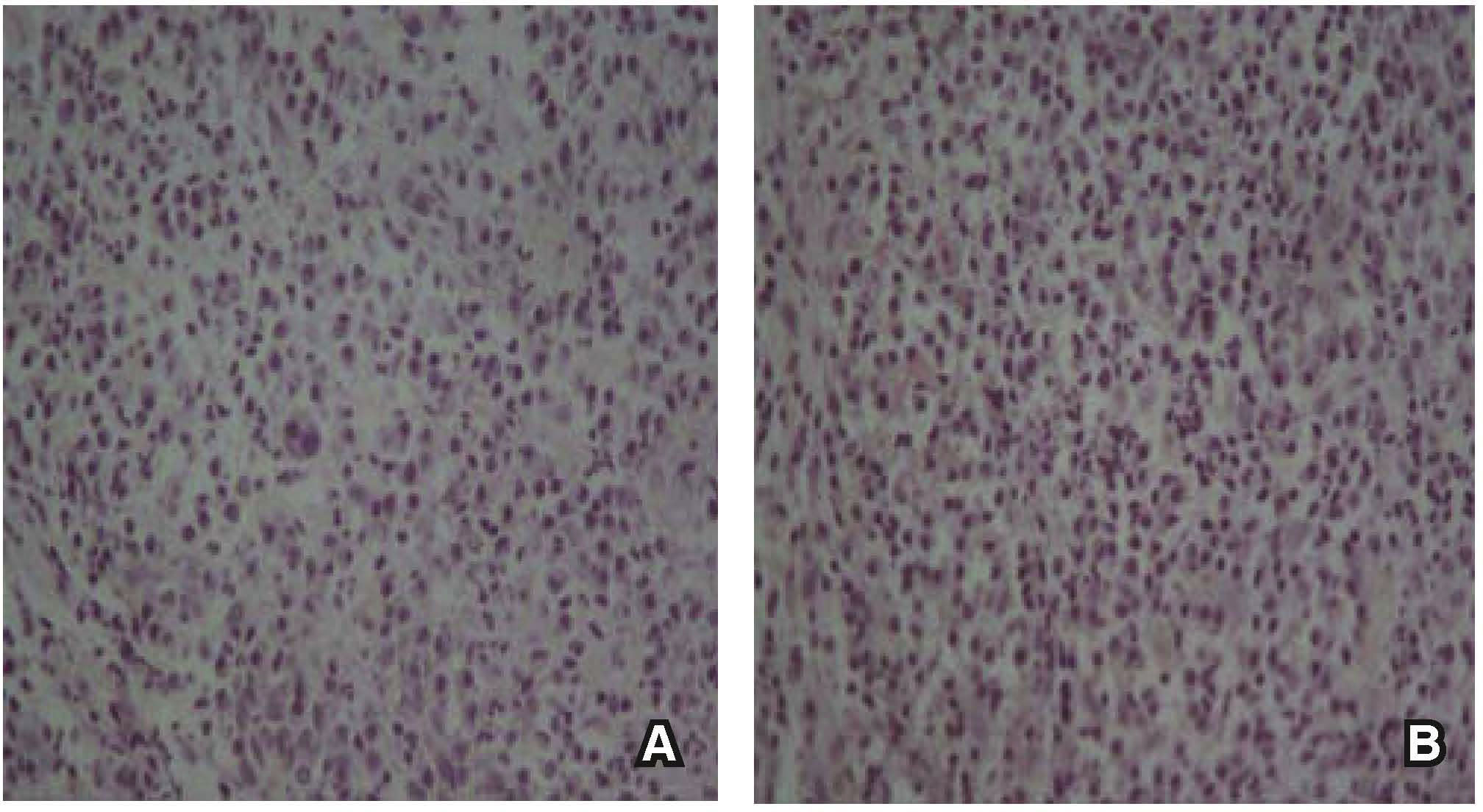

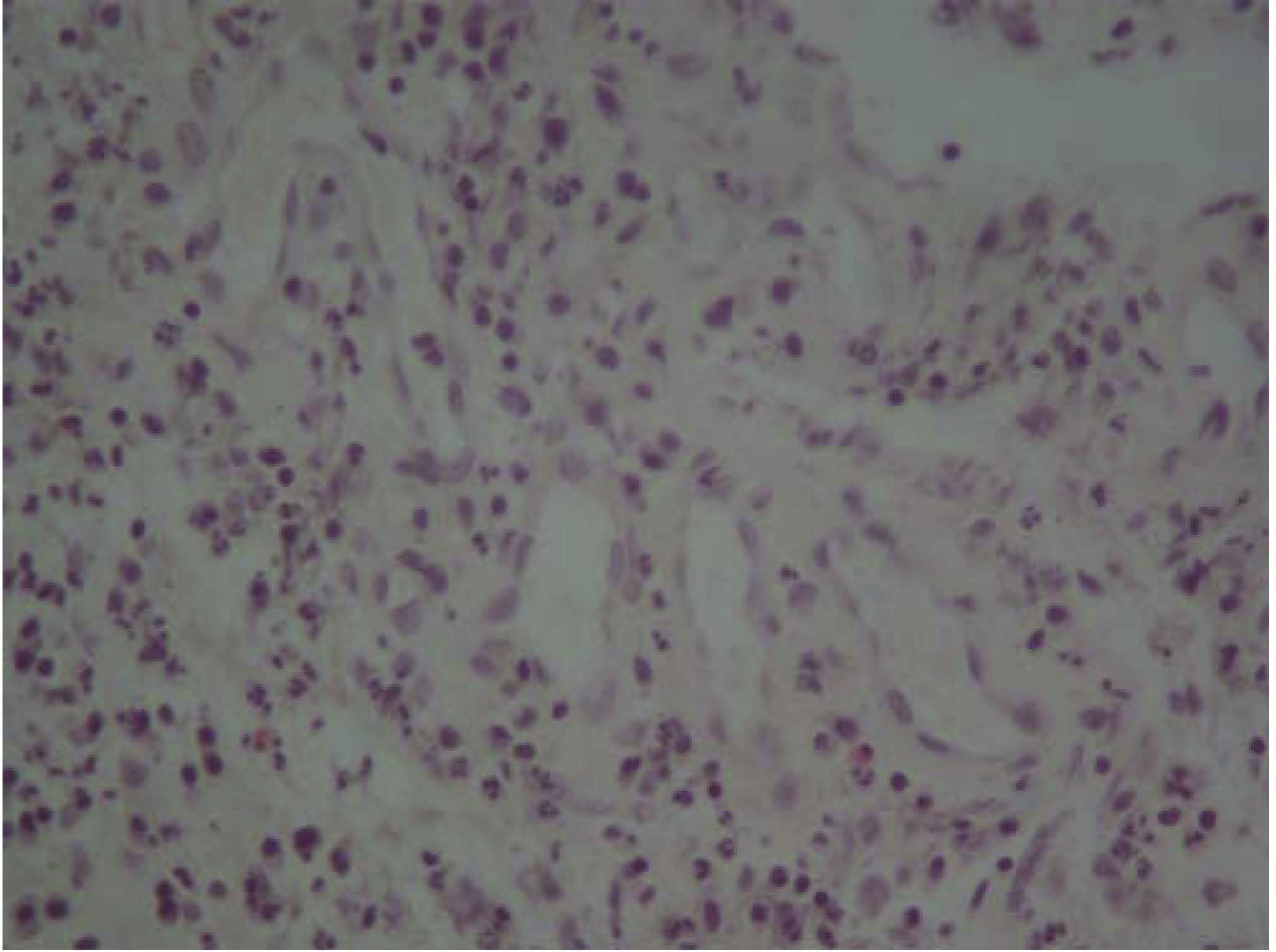

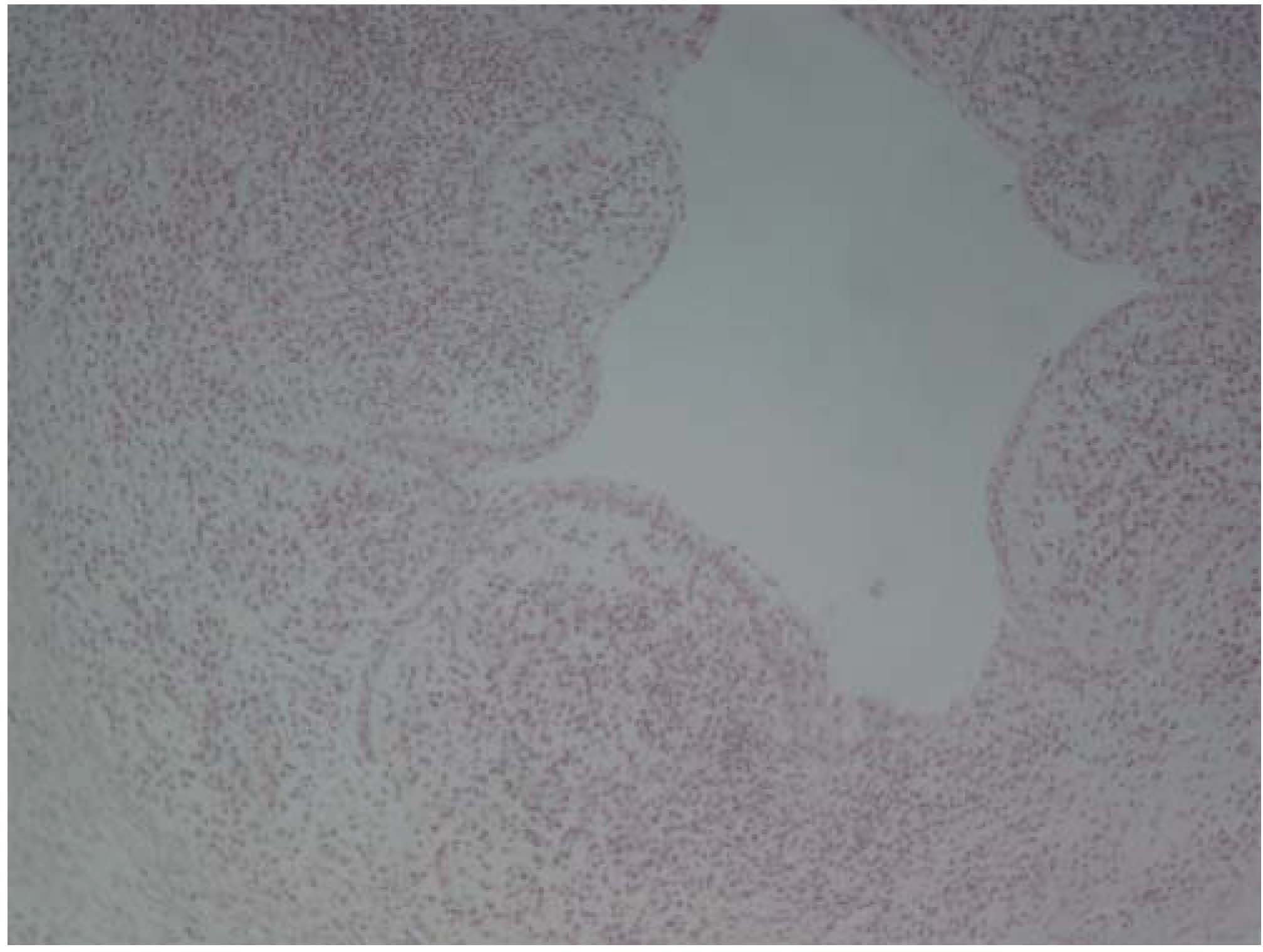

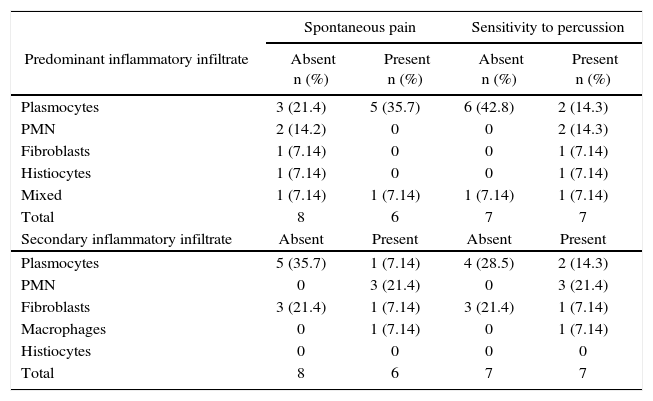

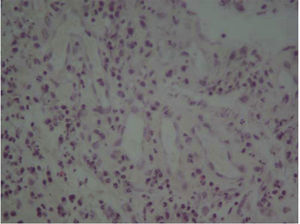

No relationship was found when spontaneous pain variable was correlated to inflammatoryinfiltrate predominance (p = 1.4), nevertheless, when this variable was correlated to secondary inflammatory infiltrate, an association between both could be determined (p = 0.057) (Table II). Likewise, correlation could be established between this variable and the neo-formation of blood vessels, finding a p value of 0.045. With respect to frequency arrangement according to the symptomatic state of patients and type of infiltrate, it could be determined that the asymptomatic group exhibited greater chronic secondary inflammatory infiltrate (plasmocytosis); the symptomatic group exhibited greatest acute inflammatory infiltrate (polymorphonuclear neutrophils) (Figures 1 to 3).

Relationship between symptomatic state of the patient and predominant inflammatory infiltrate type in the tissue.

| Spontaneous pain | Sensitivity to percussion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predominant inflammatory infiltrate | Absent n (%) | Present n (%) | Absent n (%) | Present n (%) |

| Plasmocytes | 3 (21.4) | 5 (35.7) | 6 (42.8) | 2 (14.3) |

| PMN | 2 (14.2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (14.3) |

| Fibroblasts | 1 (7.14) | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.14) |

| Histiocytes | 1 (7.14) | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.14) |

| Mixed | 1 (7.14) | 1 (7.14) | 1 (7.14) | 1 (7.14) |

| Total | 8 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Secondary inflammatory infiltrate | Absent | Present | Absent | Present |

| Plasmocytes | 5 (35.7) | 1 (7.14) | 4 (28.5) | 2 (14.3) |

| PMN | 0 | 3 (21.4) | 0 | 3 (21.4) |

| Fibroblasts | 3 (21.4) | 1 (7.14) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (7.14) |

| Macrophages | 0 | 1 (7.14) | 0 | 1 (7.14) |

| Histiocytes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 8 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

With respect to the patient’ s symptomatic status, it could be established that those who exhibited spontaneous pain also presented clinical characteristics of sensitivity to percussion, therefore, an association between variables could be established (p = 0.01).

Statistical significance was found (p = 0.023) when establishing a correlation between the mobility variable and vertical bone loss, it must be noted that dental mobility was present only in those cases where bone loss was at a severe or moderate stage. Likewise, statistical significance was found when correlating variables of affected teeth and vertical bone loss (p = 0.036), most affected teeth were those located at the lower posterior quadrant; 85.7% of all affected teeth exhibited complex crown fracture and lamina dura discontinuity.

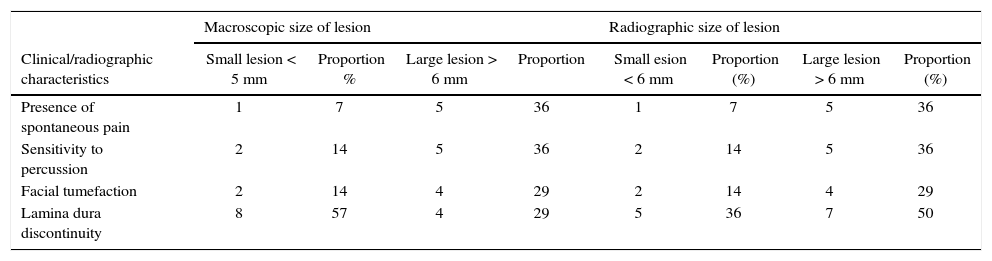

No correlation was found between radiological size of lesion and macroscopic size. Association was found when correlating macroscopic size of lesion with spontaneous pain (p = 0.01) and with sensitivity to percussion (p = 0.019), likewise, association was found when relating it to the state of the lamina dura (p = 0.05) (Table III).

Relationship between size of lesion and clinical characteristics.

| Macroscopic size of lesion | Radiographic size of lesion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical/radiographic characteristics | Small lesion < 5 mm | Proportion % | Large lesion > 6 mm | Proportion | Small esion < 6 mm | Proportion (%) | Large lesion > 6 mm | Proportion (%) |

| Presence of spontaneous pain | 1 | 7 | 5 | 36 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 36 |

| Sensitivity to percussion | 2 | 14 | 5 | 36 | 2 | 14 | 5 | 36 |

| Facial tumefaction | 2 | 14 | 4 | 29 | 2 | 14 | 4 | 29 |

| Lamina dura discontinuity | 8 | 57 | 4 | 29 | 5 | 36 | 7 | 50 |

With respect to location, it was proven that the lower posterior quadrant was the most affected, exhibiting a 42.9% frequency, followed by upper posterior quadrant which exhibited 35.7% frequency (Table III). With respect to lesion location according to tooth thirds, the apical third was the most affected exhibiting a 71.4% ratio.

No association was found between previous clinical diagnosis with histopathological diagnosis (p = 0.40). The marker «dental mobility» is found to be associated to the final histological diagnosis of periapical cyst and periapical granuloma, p value = 0.025.

No relationship was found between inflammatory infiltrate of obtained samples and presence of tumefaction.

DISCUSSIONPeriapical lesions are the most common chronic inflammatory processes found in the jaws; they are the outcome of a pulp infection which causes tissue necrosis and invades the apical region producing inflammation.19

Results obtained in this research project showed that the most affected population was composed of subjects in their third and fourth decades of life; this concurs with other reports in literature. Likewise, female gender represented the greatest population with periapical disease, showing 85% predominance in the samples.18

With respect to lesion location, Osorio,7 in 2008, reported that 83% of studied samples exhibited the apical third as the most affected, and in this study it represented 71%. This same author reported that vertical bone loss was the most frequent (50%); this figure is related with percentages found in the present research (57%).7

With respect to symptoms exhibited by the patients, no correlation was found between this variable and predominant inflammatory infiltrate, nevertheless correlation existed between the variable and secondary infiltrate (0.023), which leads to suppose that predominant inflammatory state is not related to patient's symptomatology. Conversely, secondary infiltrate would be connected to the development of clinical symptoms in the patient, such as pain, this could be explained by the exacerbation of chronic inflammatory lesions. Due to its dynamism, this characteristic is important in periapical pathological processes, since it can traverse different stages in a short time and can be influenced by the great amount of irritant agents which are present in the periapical tissue such as fragments and bacterial toxins, pulp tissue degradation products and microorganisms, as well as external factors which might influence the process such as systemic conditions.3–21

In the present study it could be observed that most processes with acute secondary inflammatory infiltrate presented spontaneous pain and pain to percussion, this was not the case for mixed and chronic processes. This could be explained due to the fact that neutrophil granulocytes (PMN) are primarily responsible for degradation of periapical tissue although their function might embody to be a protecting cell. Upon their death, they release proteolytic enzymes which degrade tissue's structural elements and extracellular matrix. This fact, combined with their short life, provokes their massive accumulation causing bone tissue breakdown and degradation in the acute phases of apical periodontitis.20

With respect to relationship of variables corresponding to symptomatology, such as sensitivity to percussion and spontaneous pain and tumefaction, it was found that sensitivity to percussion (50%) and facial tumefaction (42%) were present in half the cases; this would indicate a direct relationship with the number of cases reported with spontaneous pain (42.8%).

Among clinical markers indicating association with a diagnosis, dental mobility has been related to granuloma and periapical cyst (p = 0.025). Omoregie15 in 2009, identified carious teeth, mandibular lymphadenopathy and clinical diagnosis of dentoalveolar abscess as markers suggesting presence of an apical abscess as histological diagnosis. Likewise he found that the central incisor was the sole indicative of possible histological diagnosis of apical cyst; in this he differed from results of the present study in which upper posterior teeth were the most affected.15

The correlation existing between size of lesion and symptomatology expressed by patients should be noted. It must be stressed that patients with lesions surpassing 6mm diameter were reporting some kind of pain, this leads us to believe that lesions of greater size are related to symptom development in patients. Carrillo21 in 2008 reported the existence of correlation between the size of lesion with histological diagnosis, showing that greater sized lesions corresponded to periapical cysts, nevertheless, in the present study, this association was not found. The same author reported that 68% of all lesions was present in the upper jaw, whereas in the present study it was found that both jaws were equally affected.21

The lack of association between clinical and histopathological diagnoses as well as the absence of clinical markers which might correctly identify final diagnosis of the lesions contribute to their inadequate diagnosis and treatment. Nevertheless, this situation is also influenced by the multiple proposed classifications and their scarce practicality. Classifications such as that of Weine and Seltzery Bender, based on histopathological and clinical criteria22 widely encompass all lesions, nevertheless it lacks practicality, since great amounts of variations and terminology must be employed; this hinders its application in the everyday clinic practice and leads to confusion and uncertainty.22,23

This type of disparities causes persistence of disputes and lack of consensus on the terminology to be used, This is based firstly on the impossibility of knowing and routinely diagnosing histopathological lesions, and secondly on the semantic problem which confuses dentists and specialists alike, due to the different terminologies and classification published, which have caused controversy and hindered clinical application, when what is really needed is to establish a rational treatment plan targeting a specific pathological entity.22,23

As part of the limitations encountered in the present research paper we find the absence of a representative sample, therefore we would beg to suggest achieving further research with a larger sample.

CONCLUSIONSBearing in mind research limitations, results obtained suggested that dental mobility was identified as a possible granuloma and periapical cyst marker. Nevertheless, the absence of additional clinical markers to indicate presence of any kind of lesions as well as the dynamism characterizing these processes hinders accurate clinical diagnoses.

Association between type of lesion and symptom characteristics suggest that greater sized lesions are those eliciting some sort of symptom in the patients.

With respect to pain and histological findings we might suggest that periapical processes follow their evolution according to the secondary inflammatory infiltrate they might exhibit, and this situation favors presence or absence of symptoms.

This article can be read in its full version in the following page: http://www.medigraphic.com/facultadodontologiaunam