The objective of the present study was to determine association between orthodontic movement type and gingival recession after orthodontic treatment.

Material and methodsA series of clinical cases of 15 young patients. Circumstances of the protective periodontium of anterior upper and lower teeth were assessed before and after orthodontic treatment. Gingival recession type was assessed with Miller's classification, orthodontic movement type was classified into: vestibular inclination, protrusion, retrusion, intrusion, extrusion and combined movements.

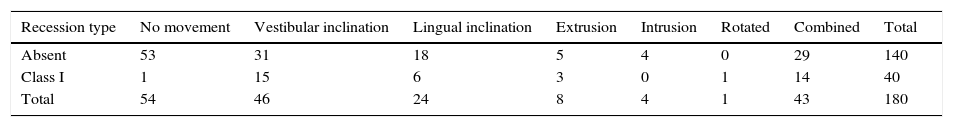

ResultsOut of 180 teeth examined, 22.2% exhibited Miller class I gingival recession; 27.5% of all gingival recessions were associated to vestibular inclination movements. No association was found between type of orthodontic movement and presence of gingival recession (p > 0.05).

ConclusionThe amount of postoperative gingival recessions observed after orthodontic treatment was negligible and did not show association with orthodontic movement type.

El objetivo del estudio fue determinar la asociación del tipo de movimiento ortodóntico y recesiones gingivales luego del tratamiento ortodóntico.

Material y métodosSerie de casos clínicos que incluyó a 15 pacientes jóvenes a quienes se evaluó la condición del periodonto de protección de los dientes anterosuperiores y anteroinferiores antes y después del tratamiento ortodóntico. El tipo de recesión gingival fue evaluado a través de la clasificación de Miller; el tipo de movimiento ortodóntico fue clasificado como: movimientos de vestibularización, protrusión, retrusión, intrusión, extrusión y movimientos combinados.

ResultadosDe un total de 180 piezas dentarias evaluadas, el 22.2% evidenció recesiones gingivales Miller clase I. El 27.5% de recesiones gingivales fueron asociadas con movimientos de vestibularización. No se encontró asociación entre el tipo de movimiento ortodóntico y la presencia de recesiones gingivales (p > 0.05).

ConclusiónLa cantidad de recesiones gingivales postoperatorias al tratamiento ortodóntico es pequeña y no posee asociación con el tipo de movimiento ortodóntico.

Recession of marginal gingival tissue is defined as the displacement of apical gingival margin towards the enamel-dentin junction with exposition of the root surface to the oral environment.1 Essential etiology of gingival recession lies with direct or triggering factors, mainly gingival inflammation, which can be caused by accumulation of bacterial plaque or mechanical means (brushing, trauma). Within the realm of indirect or predisposing factors, we can find the following: gingival biotype, thickness of bone cortical plates, amount of keratinized gingiva, root prominence and orthodontic movement.2 With respect to orthodontic treatment, it has not yet been demonstrated that it might cause gingival recession. Nevertheless, it has been reported that movement of teeth towards a vestibular direction, outside of the alveolar bone sheath, generates loss of oral cortical plate and decrease in gum thickness due to the narrowing of gingival tissue fibers.3 Vassalli4 systematic review did not find compelling evidence to support or refute relationship between orthodontic movements and onset of gingival recession. Nevertheless, he reported that clinical studies have shown that tilted teeth and incisors previously mobilized out or their socket, exhibited greater tendency to develop gingival recessions. Other authors have indeed found positive correlation between prominent roots and presence of gingival recession5 as well as between misplaced teeth and gingival recession.6 It has been clearly shown in primates that vestibular inclination, extrusion and rotation of incisors result in gingival recession and loss of clinical attachment.7 Nevertheless, the amount of labial movement, magnitude of the force, presence or absence of bacterial plate, as well as gingival inflammation might alter soft tissue during orthodontic treatment.8,9 In the present research project, association between type of orthodontic movement and presence of gingival recession was assessed, after having conducted orthodontic therapy. We hypothesized that there was no association between orthodontic movement and gingival recession in upper and lower anterior teeth.

MATERIAL AND METHODSDesignThe present study was of an observational, prospective and longitudinal nature (series of clinical cases).

PopulationFifteen patients participated in the present study. Patients were systemically healthy, ages ranging 18-30 years, and had attended the Dental Clinic Orthodontic Service at the Faculty of Dentistry, San Marcos University (Universidad Mayor de San Marcos) during 2013-2015. Sample was selected in a non-probabilistic, convenience fashion.

Bioethical considerationsStudy protocol and informed consent were approved by the ethics committee of the School of Dentistry, National University of San Marcos, and were developed according to ethical norms of the Helsinki Declaration.10

Selection criteriaAll patients were questioned with respect to treatment requirements in order to correct tooth malposition or malocclusion in upper and lower sectors. Subjects required to exhibit probing depths lesser than 4mm aqs well as being non smokers (considered as ASAI). At study initiation they had to show efficient dental plaque control with Oral Hygiene Index (OHI) lesser than 20%. Patients had to be diagnosed with mild to moderate malocclusions in anterior sectors without need of complex orthodontic treatment.

Exclusion criteriaThe following patients were excluded: patients with systemic diseases (ASA II, III, IV), pregnant females, smokers, alcoholics, patients in a treatment plan including complex surgical procedures in the anterior section (considered class II and III), patients with diagnosis of deep open- or cross-bite in the anterior section, as well as those patients who could not exhibit a suitable and correct control of dental plaque.

Variable recordingPreoperative data were assessed before initiating orthodontic treatment. Main variables recorded were: Presence of gingival recession (GR), such as apical migration of the gingival margin with respect to the enamel-cement junction line and catalogued according to Miller's classification (class I, II, III, and IV).11 Gingival recession and gingival biotypes were assessed with a 15mm WHO millimetric periodontal probe. Evaluation was conducted at the level of anterior upper and lower teeth. The same data were re-assessed at the end of orthodontic treatment, additionally, the type of orthodontic movement was recorded according to appliances and treatment plan selected by the orthodontist. Types of movement were catalogued as: vestibular inclination, lingual inclination, intrusion, extrusion, protrusion, retruded version, rotated version, combined movements and lack of movement. Each movement was assessed in all teeth, if modification of movement was found during the 2-3 years of the orthodontic treatment, movement was considered of a combined nature.

Data analysisStatistical package SPSS 21 for data analysis was used. Qualitative variables were expressed in function of graphs and frequency tables. McNemar's test was used to determine significance levels of clinical changes between two times. Association between variables was achieved with χ2 test and Fisher's exact test. P < 0.05 was accepted for refutation of the null hypothesis.

RESULTSFifteen patients were evaluated: seven males and eight females, average age 22 ± 3.75 years; 180 anterior upper and lower teeth were assessed from the whole group of patients, (from canine to canine).

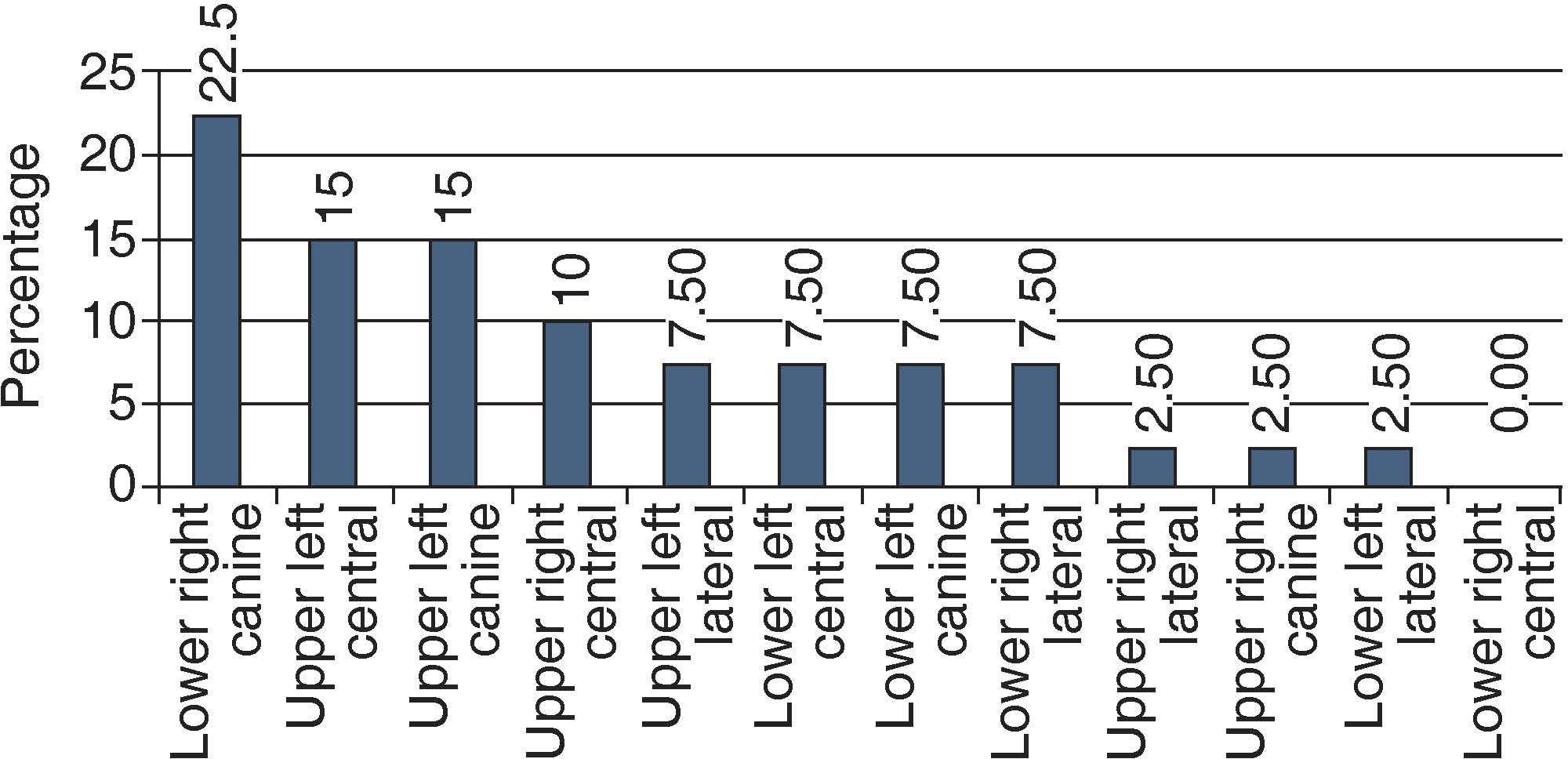

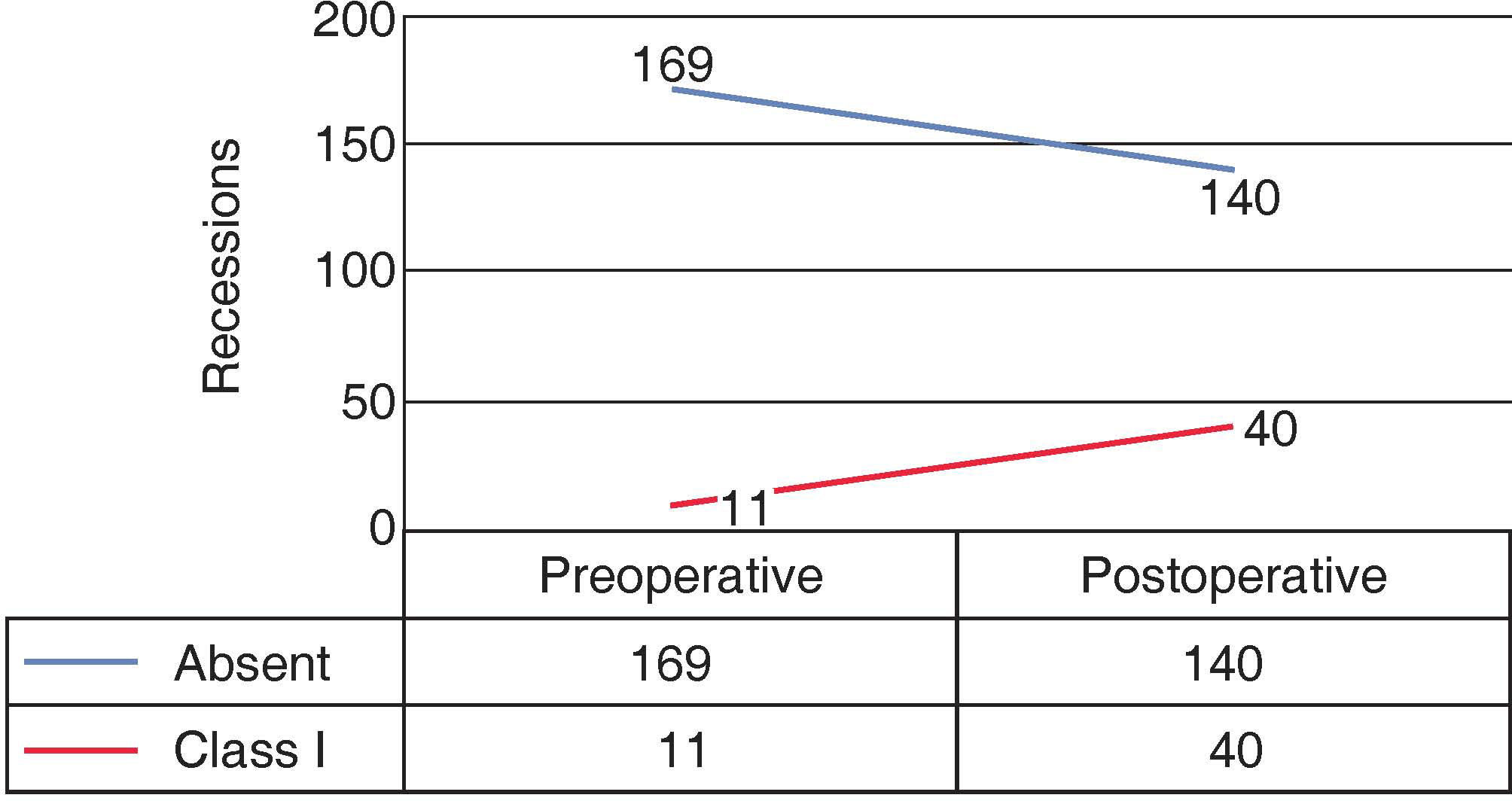

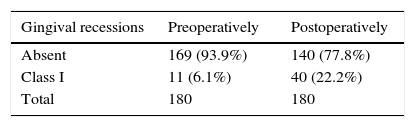

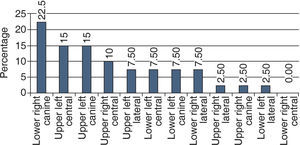

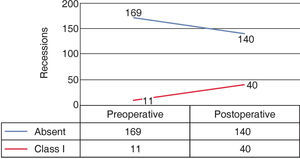

At a preoperative level, 169 teeth (93.9%) did not show gingival recession; 11 cases (6.1%) exhibited class I recession. At postoperative level, 140 teeth (77.8%) did not show gingival recession and 40 teeth (22.2%) exhibited class I recession. Most cases of gingival recession corresponded to lower right canines (22.5%) (Table IandFigure 1).

Fifteen teeth (37.5%) exhibited gingival recession subjected to vestibular inclination movements, 14 teeth (35%) showed recession caused by combined movements. Intrusion movements did not cause postoperative gingival recession (Table II). No association was found between type of gingival recession and orthodontic movement (Fisher exact test = 0.94; p > 0.05).

None of the studied teeth, neither preoperatively, nor postoperatively. Showed class II, III and IV gingival recession.

Initially, 11 teeth were found with gingival recession; 40 gingival recessions were found after orthodontic treatment (2.5 years was average length of treatment), this represented a change for 29 teeth with class I recession, as well as significant difference according to McNemar’ s test (p < 0.01) (Figure 2).

DISCUSSIONMovement of anterior teeth outside alveolar bone has been studied for years as a source of gingival recession.12 Clinical appreciation of vestibular inclination must not automatically pre-suppose existence or progression of a future gingival recession process. Our study did not find association between type of orthodontic movement and presence of gingival recession. Recession was more common in teeth subjected to vestibular inclination movements, nevertheless, this figure was not ample enough to infer an association. Other factors might bear influence in this association: poor oral hygiene, gingivitis, fine gingival biotype, as well vestibular inclination of incisors; all the aforementioned factors might elicit certain degree of gingival recession.13,14 All cases requiring orthodontic treatment must begin with a periodontal diagnosis. It is important for the orthodontist to be able to accurately diagnose presence of a periodontal problem at initial stages, thus preventing evolution to other phases with irreversible effects.15 Assessment of the periodontium's circumstances (width of the gingiva and gingival biotype) before initiating orthodontic treatment will allow to count with prognosis of the evolution of periodontal and muco-gingival conditions.

In our study, significant differences in gingival recession were found at preoperative and postoperative levels. Postoperative level recessions were treble the amount of those found at basal level (40 cases, versus 11 cases), this would prove that preoperative circumstances of the periodontium, unrelated to orthodontic movement, might bear influence in the onset of further gingival recession.

It is worth mentioning that the study targeted assessment of association types between recessions and orthodontic movement. It is possible to establish even more associations, such as amount of gingiva, gingival biotype, vestibular cortical thickness and type of orthodontic movement. These associations are a recommended subject for further research projects. Coatoam,12 in a retrospective study of 100 patients, found that teeth exhibiting scarce amounts of keratinized gums before orthodontic treatment did not form gingival tissue after treatment. A 6.1% full loss of keratinized gingival tissue was found in teeth with less than 2mm of keratinized gums. Joss-Vassalli,4 in his systematic review exposed that teeth with protrusion tendency suffer higher probabilities to develop recessions. He stresses the fact that there are very few studies conducted in humans to support this conclusion. A periodontal parameter to consider from the orthodontic point of view is the amount of existing attached or keratinized gingiva. In the case of reduced keratinized gingival tissue, displacement of a tooth must imply periodontal surgery techniques before the treatment, these techniques can be based on flaps, or grafts, before undertaking orthodontic movement. Proinclination or protrusion of a tooth decreases attached gingiva; finally, surgery should be conducted before initiating orthodontic treatment. Conversely, dental retro-inclination and extrusion foster formation of attached gingiva, therefore, mucogingival surgery should be postponed.16 Since appliances hinder tooth cleansing, it is of the utmost importance to motivate and instruct patients in oral hygiene programs before and during treatment. As part of this program, it is recommended for the periodontal specialist to conduct bi-monthly reviews which must include prophylaxis whenever needed.17 In spite of the study's limitations, we could summarize that orthodontic dental movement by itself does not cause soft tissue recession, nevertheless, a thin gingiva which might be the consequence of vestibular inclination movement of the teeth could well be a site of lesser resistance to the development of soft tissue defects when in presence of bacterial plaque and/or trauma caused by an inadequate brushing technique. Before initiating orthodontic treatment, it must be carefully pondered whether the bucco-lingual thickness of soft tissues in the pressure side of the teeth should be increased. Moreover, suitable instructions on plaque control measures must be provided and controlled before, during and after orthodontic therapy completion in order to avoid unnecessary trauma to the marginal tissue.

CONCLUSIONS- •

The amount of gingival recession after orthodontic treatment is low, exhibiting a 22% incidence.

- •

Vestibular inclination movement is the main orthodontic force causing gingival recession after treatment.

- •

There is no association between type of orthodontic movement and type of gingival recession after orthodontic treatment.

DDS.

This article can be read in its full version in the following page: http://www.medigraphic.com/facultadodontologiaunam