To study the influence of adolescence characteristics on asthma management.

MethodsThis was a qualitative study conducted in the city of Divinópolis, Minas Gerais, Southeast Brazil. Data were collected through semistructured interviews guided by a questionnaire with seven asthmatic adolescents followed-up in the primary public health care service of the city.

ResultsUsing content analysis, three thematic categories were observed in the adolescents' responses: 1) family relationships in the treatment of asthma in adolescence; 2) the asthmatic adolescents and their peers; and 3) the role of the school for the asthmatic adolescents.

ConclusionsThe results demonstrated that peers, family, and school should be more valued by health professionals and by health care services when treating asthmatic adolescents, as these social relationships are closely associated with the adolescent and have an important role in asthma management. Attempts to meet the demands of adolescents contribute to improve asthma management.

Conhecer a influência das características da fase da adolescência no manejo da asma.

MétodosTrata-se de um estudo descritivo de abordagem qualitativa realizado no município de Divinópolis, região centro-oeste de Minas Gerais. Os dados foram coletados por meio de entrevistas semiestruturadas orientadas por um roteiro de perguntas junto a sete adolescentes asmáticos atendidos na rede de atenção primária à saúde municipal.

ResultadosPor meio da análise de conteúdo na modalidade temática foram construídas três categorias analíticas: 1) As relações familiares no tratamento da asma na adolescência; 2) O adolescente asmático e seu grupo; e 3) O papel da escola junto aos adolescentes asmáticos.

ConclusõesOs resultados mostraram que o grupo de pares, a família e a escola devem ser mais valorizados pelos profissionais e pelos serviços de saúde, pois essas instâncias se relacionam intimamente com o adolescente e têm papéis importantes no tratamento da asma. A tentativa de atender às demandas do adolescente contribui para a melhoria do manejo da asma.

Asthma is considered a public health problem worldwide.1 According to Brazilian data, it is the most common chronic disease in adolescence and the third leading cause of hospitalization in this age group.2 An international study including several cities in Brazil demonstrated that asthma among Brazilian adolescents aged 13 to 14 years had a mean prevalence of 19%.3 Therefore, it is essential to provide expert care in health services to adolescents with asthma to better manage and control the disease, aiming at appropriate treatment adherence.4

Other investigations have shown that adherence to asthma treatment is much more than simply treating the focus of the disease. It goes beyond, comprising patient agreement and consent to the proposed treatment, which in the case of asthma involves the use of medications, control of environmental allergens and irritants, and health service monitoring. Treatment adherence takes into account the health professional-patient relationship5 and determines the recognition and appreciation of something that is much more complex than protocols, standards, and consensuses: the patients who experience the disease in their daily lives. It is of utmost importance to know how they cope with their limitations and adapt to the disease burden.

During adolescence, changes and adaptations are intense and comprehensive in the overall context of the individual's life, and can be generally aggravated when there is a preexisting diagnosis of asthma or when the diagnosis is made at this period of life. This is because, in addition to the changes and adaptations inherent to adolescence, the adolescent will have to cope with the changes caused by the disease and those required by the treatment.

In the public health care system, asthma treatment is performed at all levels of care: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary health care is considered an essential level in the treatment of asthma, as it is able to perform diagnosis, treatment, control, and monitoring of most of these patients, providing better access to care and identifying the environmental conditions in which these patients live.

Being subject to such actions in the context of health services, asthma is considered a primary care-sensitive condition, that is, a health problem that can have its risk of unnecessary hospitalization decreased through effective primary care actions.6 The decrease in the number of hospitalizations for asthma directly reflects in the costs of the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS), which, in 2010, had approximately 193,000 asthma-related admissions, generating an approximate expenditure of R$ 100.8 million.7 The comprehensive care of adolescents comprises the possibility of extending the health care professional's actions, whose concerns include the uniqueness of the subject and also the organization of services. Thus, the space once considered the “professional's place” - a place of power - becomes another, in which greater interaction is sought between professionals and the assisted population. Instead of considering that the adolescents should adjust their behaviors according to a preset model, the professional shall consider the subjects in the context of their lives as a factor of utmost importance to understand the patient's problems. The ethical dimension involved in this strategy concerns the fact that, in this relationship, the physician should consider the adolescent as an individual and not as a mere object of research.8

Considering these facts and in order to contribute to the implementation of this comprehensive care, this study aimed to evaluate the influence of the adolescence characteristics on asthma management from the perspective of the adolescents assisted in primary care.

MethodsThis was a descriptive qualitative study. This type of research, which has been increasingly used, allows for the understanding of beliefs and attitudes on sensitive topics, in which the intimate and truthful relationship with research subjects can provide access to data that would not be accessible through quantitative methods.9

The research was developed in the area comprehending Health Sectors 8 and 11, located in the northeastern region of the city of Divinópolis, state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The eligible study population consisted of 21 patients with persistent asthma (10 males and 11 females), aged between 10 and 19 years, who lived in this area.

The choice to study adolescents with persistent asthma was based on the chronic aspect of the disease, which, in such cases, has a higher possibility of limitations for physical activity, sleep loss, need for monitoring in health services, and routine use of medications that may result in side effects. Thus, the quality of life of individuals with persistent asthma may suffer higher impact on both the individuals and their families.

Semi-structured interviews were performed following a questionnaire. Seven interviews were performed, as there was data saturation: there were no more new theoretical insights or disclosure of new properties on the study object.10 All interviews were performed by the same investigator (AA), a faculty professor and nurse with experience in clinical care of children and adolescents with asthma, as well as in collecting and analyzing data for qualitative studies.

The interviews were recorded with a MP4 recorder. Then, they were transcribed by the researcher, and their content was compared with the recording. These data were submitted to content analysis considering the theoretical framework of Bardin,11 which recommends the following steps: pre-analysis, material assessment and processing of results, and interpretation.

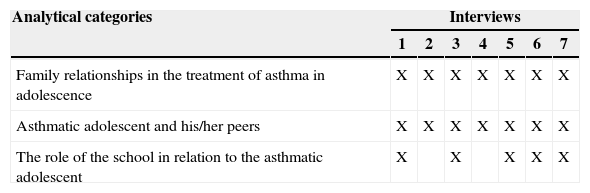

Strictly in accordance with the steps described in the procedures to verify theoretical saturation,11 record units12 were identified, i.e., the smallest clippings of speeches, chosen based on the research objectives and that means something about the addressed object of study. These record units allowed for the creation of three analytical categories (Table 1), which, in turn, were joined in the broader category: being an adolescent and living with asthma.

Distribution of analytical categories according to the origin of the log units identified during the interviews in 2011 (X = presence of log units).

| Analytical categories | Interviews | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Family relationships in the treatment of asthma in adolescence | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Asthmatic adolescent and his/her peers | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| The role of the school in relation to the asthmatic adolescent | X | X | X | X | X | ||

The study was performed from October to December of 2011, after approval by the institutional review board of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, protocol No. 435 of October 4, 2011.

Results and discussionFamily relationships in the treatment of asthma in adolescenceIn spite of all the relevance that peer groups have in the formation of adolescent identity, the family is also crucial at this stage of the individual's life, as parents are the first identification references. Adolescence does not mean a rupture with the family, but rather a transformation of childhood bonds into a more mature, independent, and tolerant (less idealized) bond with the parents.13

During this process, certain family conflicts are necessary and important, as they are related to transformation and adjustment tasks that individuals must accomplish in order to achieve full performance of their roles. Among asthmatic adolescents, the transition from dependence to independence includes accomplishing tasks beyond those typical of adolescence. It includes the treatment of asthma, which requires the use of certain medications and behaviors, as well as coping with unwanted symptoms, which demonstrate lack of disease control or poor compliance:

No, my mother is more demanding; my mother is the one that reprimands the most: “Blackberry, have you not taken the medicine yet? What did you do? You had cold drinks at night, didn't you? Did you wash your hair?” Got it? My mother is like that … She will not let me wash my hair at night, have cold drinks… It bothers me when my mother keeps talking and talking … I know what I can and what I can't do… I'm a grown up, now, I know, I know how to take care of myself since I was small, because my parents are divorced, so I learnt how to take care of myself. Even with my meds, my mother no longer needs to tell me all the time: Baby, take this… baby, take that … (Blackberry)

My mother yells all the time, for instance, when I wake up in the morning she talks to me like that: “Go make your bed, brush your teeth, and get dressed to go to school”, then I forget to make the bed! I do the other stuff, and then she starts calling me names. I wake up very tired; I stay the whole day at school. I wake up a lot during the night and that is why I am sleepy in the morning. (Cashew)

Asthmatic adolescents also reported the constant vigilance of parents, mentioning several warnings about everyday treatment. This attitude of the parents is relevant, because adolescents with persistent asthma have higher risk of death, which may be related to failure to comply with the prophylactic treatment.14

It's just that when I start sneezing and coughing, my mother starts saying: “Use the inhaler! …” All the time: “Use the inhaler, use the inhaler!” Then I go and use the inhaler … So I won't have a crisis … (Pomegranate)

[…] My father gets so worried if a window is open, if there is anything making the air humid. Then, when I'm sick, he already knows … (Blackberry)

Even with so many conflicts and reprimands, the respondents do not forget the important support from parents and families, both during crises at home and hospitalizations.

When I am wheezing, my mother has to stay awake with me, because difficulty breathing and wheezing are usually stronger at night. My mother stays up all night. (Fig)

When I was younger, everyone went crazy because I had to go to the hospital, but not anymore. And now, that is bad for me, everybody used to pamper me … and now it is over. But I deal with this. (Apple)

However, the leniency and carelessness by for some family members are also present in the daily life of asthmatic adolescents.

They don't care. They don't say anything. My dad sometimes tells me to take my medications properly, though. (Pitanga)

With the indispensable monitoring in the treatment of their children, parents greatly contribute to good self-care practices and beliefs. These individuals, who are part of the adolescents' daily life, influence behaviors that promote treatment adherence and thus, control the disease.15

The asthmatic adolescents and their peersAt other times, the adolescents emphasized group behaviors16 that may put them, whether or not consciously, in situations of risk, ranging from the contact with factors that can trigger the asthma crisis, such as dust, allergens, and cold, to group behaviors and attitudes:

I run with my cousins and play in the dirt… Our clothes become black with dust. (Orange)

Hot body in cold water, that is because I cannot control my desire. Then you see all your friends entering the water and I cannot control myself. (Fig)

If I go to the shopping mall with my friends, I have to take my inhaler because of the air conditioning there, and I don't do very well with air-conditioning. I have to take the inhaler, so I have to take a purse. Nobody is carrying a purse, and I have to carry one! I look different from other people. And, like, it's bad, because everybody's hands are free, and I'm holding my purse! I went out without a purse once and got sick. It was the last time we had the Circus and Amusement Park here in Divinópolis. I said well, I'm not taking the purse today! I took only what I could fit into my pockets: an ID and money. I left home at half past seven, at eight o'clock I started to feel sick. Then my father had to pick me up.(Blackberry).

These statements regarding the group of friends are related to chronic illness in adolescence, which appears to reorganize around the social support,17 especially from friends, in relation to the patient. The disease also appears to restrict self-disclosure and intimacy in matters directly related to the disease, on both sides.18

The role of the school in relation to asthmatic adolescentsIn addition to family and friends, the school is another very important aspect of the adolescent's life. It is within the family environment, and later at school, that the individual humanizes and socializes, as the biological, cognitive, and interpersonal needs are met. The support given by education has an impact on the establishment of personal and social projects, as that is what gives meaning to human life.19 For the adolescent who lives with a chronic illness such as asthma, the disease itself and the treatment interfere with school performance, requiring “a joint work between health professionals and educators, ensuring the maintenance of formal education and healthy social relations”.20

Among the interviewees, only one adolescent did not attend school, as she had missed many school days due to the asthma, which compromised her school year.

I stopped studying this year, in the first year of high school. And now I'm not studying. I stopped because I was wheezing; I missed the months of July and August. I even went after that, but it was hard to follow. You want to do something, you try, but you can't deal with it! But I will go back to school at night. (Pitanga)

School absenteeism21 is a constant in the life of asthmatic adolescents due to the crises, which usually do not require frequent hospitalization, as in childhood, but home treatment.

I only miss classes when I have to. In October I had to, I had to go to the doctor, at another Primary Health Care Center. I went to see him because of my asthma. (Pomegranate)

When I was younger, I missed a lot of classes because I was at the hospital. And now because of the disease, I stay at home. This year I missed a lot of classes! Four times in one month! I have not missed any classes this month of November; I had to take my examinations. When I feel sick, I don't go to school. (Apple)

Being an extension of the home, the school must be included and participate in the required care of the student with asthma. The school environment is not always appreciated as important for the continuity of home care, such as the student's condition and treatment, which may, at some point, involve physical activity restriction, allergen control, use of new drugs, and following treatment schedules, among others.

I do the usual activities, physical education, I run at recess. (Orange)

At school, there were many children who also missed classes, like that. And they [school] asked that when the person had the flu, bronchitis, they should not to go to school. They said that we should not go. We have to take our meds correctly. (Pitanga)

I take the inhaler to school, because when it is time to use it, I have to do so. (Fig)

School participation can contribute to the understanding of the educational needs of adolescents and establish collaborative individualized measures for prevention, identification, and treatment of crises. Asthmatic adolescents have difficulties related to access to and use of their medications during school hours, which can impair adequate disease management. Thus, it is necessary to establish school health protocols tailored to the needs of these students, developed together with the adolescents, parents, and health and school professionals.22

Final considerationsThe results of this study demonstrate that adequate asthma management among adolescents demands more attention from health professionals and health services that goes beyond the use of medications, allergen control, and attendance of medical appointments. The statements from adolescents with asthma demonstrated that there are differences and specificities in the treatment of asthma that stem from the uniqueness of the subject and their stage of life: adolescence.

The realization that the peer group has a dubious role in the daily life of the asthmatic adolescent is crucial, as while it stimulates collective behaviors that can cause crises, it also supports coping with the disease and provides the necessary adolescent identity to the subject. Exploring the group trend of this phase of life through the strategy of an educational group with asthmatic adolescents can contribute to the care of this specific population.

The acknowledgement that family conflicts related to asthma treatment in adolescents are based on the process of becoming independent favors the understanding that skills and expertise in asthma care are mediated by the health professionals caring for the adolescent and his family. It is the professional's responsibility to identify and recognize aptitudes, difficulties, and potentialities of those involved in the asthma management tasks without disturbing the fulfillment of their distinct roles in family dynamics: what the adolescent can do on his own and what he/she need the help of his/her parents to accomplish.

It is also necessary to consider the school as an integral part of the asthmatic adolescent care network. Getting teachers and school officials acquainted with their student's condition might be easy, but to get involved in care demands a greater effort, in which the school/family/health service relationship needs to be closer. In this field, the establishment of means of communication and referrals, as well as training school workers regarding some aspects of asthma in adolescence, is crucial to provide care to the asthmatic adolescent at school.

However, it is necessary that the results of this study are considered and addressed effectively in health care services for the adequate care of asthmatic adolescents. It is essential, for better adherence to asthma treatment, to understand that it is during adolescence that the individual acquires better knowledge of the disease. Thus, overcoming the challenge of comprehensive care for adolescents corroborates to treatment adherence.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.