The aim of this cross-sectional study was to investigate an association between the prevalence of root-filled teeth (RFT) or apical periodontitis (AP) and some systemic conditions or smoking habits in an adult Portuguese population.

MethodsMedical histories, including age, gender, presence of cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes mellitus (DM), allergies, smoking status, and endodontic treatment data of 421 patients (10,540 teeth) were recorded. The prevalence of root filled teeth and the periapical status were assessed through panoramic radiographies. Periapical status was classified according to the Periapical index and AP was defined as PAI-score ≥3. Statistic analysis was performed with PASW Statistics 20.0 using qui-square tests, odds-ratio and confidence intervals (95%).

ResultsThe overall prevalence of AP and RFT was 2.2% and 4.2%, respectively. RFT increased the possibility of having AP (p<0.0001). Men's group showed a higher percentage of teeth with AP (p<0.0001), less RFT (p=0.05) and more residual roots (2.3%). Smoking increased the probability of having AP (p=0.002) and RFT (p=0.045). A positive correlation was observed between RFT and DM (p=0.040). No statistically significant difference was found between AP and CVD, DM or allergies neither between RTF and CVD or allergies.

ConclusionsThe higher prevalence of AP and/or RFT in smoker subjects and in diabetic patients can suggest a relationship between oral and systemic health. More epidemiological studies are required before definitive conclusions can be made.

O objetivo deste estudo transversal foi investigar a associação entre a prevalência de dentes com tratamento endodôntico (RFT) ou periodontite apical (AP) e algumas condições sistémicas ou hábitos tabágicos numa população adulta portuguesa.

MétodosHistórias médicas, incluindo idade, género, presença de doenças cardiovasculares (CVD), diabetes mellitus, alergias e hábitos tabágicos, e registos dos tratamentos endodônticos de 421 pacientes (10.540 dentes) foram recolhidos. A prevalência de dentes com tratamento endodôntico e status apical foram avaliados através de radiografias panorâmicas. O status apical foi classificado de acordo com o índice periapical e a AP definida para valores PAI≥3. A análise estatística foi realizada através do PASW Statistics 20.0 utilizando os testes chi-quadrado, valores odds-ratio e intervalos confiança (95%).

ResultadosA prevalência da AP e RFT foi de 2,2% e 4,2%, respectivamente. RFT aumentou a possibilidade de ter AP (p<0,0001). Os homens revelaram uma maior percentagem de dentes com AP (p<0,0001), menos RFT (p=0,05) e mais raízes residuais (2,3%). Fumar aumentou a probabilidade de ter AP (p=0,002) e RFT (p=0,045). Uma relação positiva foi observada entre RFT e DM (p=0,040). Não se encontraram diferenças estatisticamente significativas entre AP e CVD, DM ou alergias nem entre RTF e CVD ou alergias.

ConclusõesUma maior percentagem de AP e/ou RFT nos fumadores e nos pacientes com diabetes sugere uma relação entre a saúde oral e sistémica. Mais estudos epidemiológicos são necessários antes de se fazerem conclusões definitivas.

Apical periodontitis (AP) is “an acute or chronic inflammatory lesion around the apex of a tooth caused by bacterial infection of the pulp and root canal system”.1 The inflammatory cells cause, among other effects, resorption of the adjacent supporting bone. The diagnosis is primarily based in the observation of a periradicular radiolucency, although it can be supported by patient’ symptoms or clinical signs in the acute phases.1,2 AP is highly prevalent, and the estimated percentage of individuals with AP, in at least one tooth, is 34–70%3-7, which can rise in older patients.8–11 Overall, the percentage of teeth with AP has been estimated to range between 1.7% and 6.6%.5,9,12 However, amongst endodontically treated teeth the percentage is significantly higher.9,11,13–16

Root canal treatment is the most frequent therapeutic option for preserving teeth with AP and to restoring perirradicular tissues’ health. Therefore, its prevalence can be linked to the presence of severe caries lesions or traumatic injuries that lead to pulp necrosis. The prevalence of individuals with, at least, one root canal treatment is between 41 and 87%.5,7,17,18 The frequency of root-filled teeth varies between 2.2% and 9.39%.5,6,9,11,15,19 This broad variation can be due to either different age stratification in the studies or variation within national health care services.

Several epidemiological studies have found an association between chronic dental infection, cardiovascular disease (CVD)20–25, diabetes mellitus (DM)26–29 and smoking habits30,31, most of them relating to periodontal disease.

AP is, in many instances, very similar to periodontal disease regarding the microbial aetiology and the presence of elevated systemic cytokines.32,33

Patients with DM, hypertension or coronary heart disease might have decreased tissue resistance to bacterial infection and reduced ability of tissue repair after endodontic treatment. Wang et al.34 found an increased risk of tooth extraction after nonsurgical endodontic treatment in patients with these diseases. Furthermore, the association of two of those conditions was a significant predictor of extraction or poorer outcome of the endodontic treatment32,35,36. However, limited data is available on the long-term prognosis of AP and root-filled teeth, in patients with systemic diseases and smoking habits.

DM, a syndrome characterized by abnormalities in carbohydrate, lipid and protein metabolism, also affects many functions of the immune system. For instance, up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines from monocytes/polymorphonuclear leukocytes and down-regulation of growth factors from macrophages, resulting in dysregulated macrophage phagocytosis.37 Consequently, there is delay in healing process and commitment of the immune response.38,39 These events predispose to chronic inflammation, progressive tissue breakdown and diminished tissue repair capability.40–42 DM has been considered as a possible modulating factor or disease modifier in endodontic infections, in the sense that diabetic individuals, especially when poorly controlled, could be more prone to developing AP.43,44 The literature on the pathogenesis, progression and healing of endodontic pathology in diabetic patients is still scarce and show controversial results.29,43,45–47

Current evidence indicates that smoking is a significant risk factor for the inflammation of the marginal periodontium.25,48 Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies demonstrated the harmful effects of tobacco smoking on the supporting structures of the teeth.25,49 Smoking impairs the body's responses to infection, exacerbates bone loss, decreases the blood's oxygen-carrying capacity and causes vascular dysfunction.50 It can be assumed that smoking can act as a risk factor to the development AP, exerting a negative influence on the apical periodontium of endodontically compromised teeth, allowing the extension of periapical bone destruction and/or interfering with the healing and repair process after root canal treatment.25

In the recent years, there has been a high level of interest in research focused on Dentistry, namely Endodontics, related to systemic health. To date, the role of systemic conditions and health-related habits as risk factors for adverse outcome of AP has not been thoroughly explored.

The present study is aimed at exploring an association between endodontic status and systemic conditions, such as, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus or allergies, and smoking habits as possible risk factors for AP, in an adult Portuguese population.

MethodsThe sample included medical histories and endodontic treatment data of all the patients attending the clinic of the Dental Faculty of Oporto University and of the Health Sciences Faculty of Fernando Pessoa University (Oporto) for the first time in 2012. The following were used as inclusion criteria: age (at least 18 years old) and number of teeth (no less than 8 remaining teeth). 421 patients were selected, with a total of 10,540 teeth assessed. The institutional scientific committee of each of the faculties involved formally approved the present study.

Age, gender, aspects of general health (presence of CVD, DM, allergies) and health-related habits (smoking status), were recorded from the medical questionnaire. CVD, DM and allergies were assessed through a dichotomy key (yes/no). Coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension, atherosclerosis, and myocardial infarction were included in the cardiovascular disease category. Type 1, type 2 and gestational diabetes were included in the DM group. The following criteria were monitored in the allergies’ category: pollen season, asthma, atopic dermatitis, Chron's disease, rheumatoide arthritis, allergic rhinitis and allergy medication, such as penicillin.

Smoking status was classified as non-smoker, if the patient answer was never smoker/former smoker for more than 5 years ago, or current smoker.

The periapical status and the prevalence of root-filled teeth (RFT) were assessed using panoramic radiography. The Orthoralix® 9200 DDE (Gendex) was used in all cases. The method of viewing the radiographies was standardized: films were examined in a darkened room using a computer in which the ambient light could be controlled for the best possible contrast. Teeth were categorized as RFT, if they presented any radiopaque material in the pulpal space. Periapical status of each tooth was classified according to the Periapical Index (PAI)51 and the presence of AP was defined as PAI-score ≥3. In cases of multi-rooted teeth, the worst root score was chosen. Three observers performed the PAI assessment, after training and calibration. The coefficient Cohen's kappa was applied.

In order to characterize the oral health status of the subjects, additional clinical data such as the number of missing teeth as well as residual roots were also recorded.

Statistical analysis was performed with PASW Statistics 20.0 (version 20, SPSS®). A descriptive statistical study of the selected variables was performed. Data were analyzed by estimating frequencies in percentages. The association and the level of significance between two variables were evaluated using the qui-square test. The odds-ratio and the respective confidence intervals (95%) were obtained by association measures in 2×2-cross tabs. For statistic analysis tooth was adopted as sampling unit.

ResultsThe sample included a total of 421 patients’ records. From these 43% were male and 57% female, with a mean age of 41±16 years old (range 18–82 years). Of the 10,540 examined teeth, 2.2% had AP and 4.2% had RFT. The prevalence of AP was greater in root-filled teeth (Fig. 1 and Table 1) and in the men's group (p<0.05) (Table 2). The probability of having AP in men was almost two times higher than in women (Table 2).

Prevalence of apical periodontitis (AP) and root-filled tooth (RFT), residual roots (RR) and missing teeth (MM).

| Study’ population | AP | RFT | RR | MT | AP*RFT |

| 2.2 | 4.2 | 1.73 | 87.86 | 18.2 |

| Gender | Male | Female | ||||||

| AP | RFT | RR | MT | AP | RFT | RR | MT | |

| 2.82 | 3.9 | 2.28 | 84.45 | 1.7 | 4.7 | 1.31 | 90.4 | |

| Smoking status | Smoking | Non-Smoking | ||||||

| AP | RFT | RR | MT | AP | RFT | RR | MT | |

| 3 | 4.9 | 3.18 | 83.74 | 1.87 | 3.93 | 1.46 | 89.86 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | DM | Non-DM | ||||||

| AP | RFT | RR | MT | AP | RFT | RR | MT | |

| 2.4 | 6 | 0.98 | 100 | 2.38 | 4.27 | 1.96 | 86.6 | |

| CVD | CVD | Non-CVD | ||||||

| AP | RFT | RR | MT | AP | RFT | RR | MT | |

| 2.4 | 3.5 | 1.35 | 95.01 | 2.4 | 4.65 | 2.06 | 85.37 | |

| Allergies | Allergies | Non-allergies | ||||||

| AP | RFT | RR | MT | AP | RFT | RR | MT | |

| 1.6 | 5.5 | 1.2 | 88.9 | 2.5 | 4.26 | 2.02 | 87.1 | |

Values are presented as number (%).

Apical periodontitis (AP) and root-filled tooth (RFT) according to gender.

| OR | CI | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AP*RFT | 14.81 | 11.07–19.82 | <0.0001 |

| AP*Gender | 1.68 | 1.29–2.17 | <0.0001 |

| RFT*Gender | 0.82 | 0.676–1.00 | 0.05 |

Values are presented as odds-ratio (OR) and confidence intervals (CI 95%). Testing of group differences by *qui-square test. At bold (P) are the relationships between the variables that are significant.

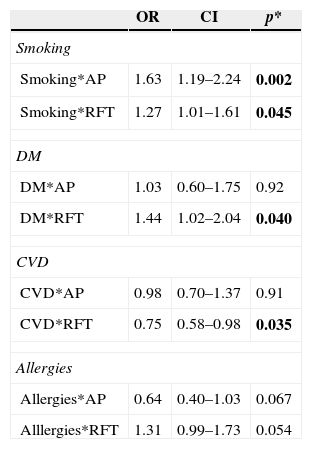

A significant association was observed between smoking status, AP and RFT (Table 3). RFT were more prevalent in DM and CVD groups (p<0.05) (Table 3). No significant association was found between AP and CVD, DM or allergies groups, neither between RFT and allergies (Table 3).

Apical periodontitis (AP) and root-filled tooth (RFT) in smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), cardiovascular disease (CVD) or allergies’ groups.

| OR | CI | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | |||

| Smoking*AP | 1.63 | 1.19–2.24 | 0.002 |

| Smoking*RFT | 1.27 | 1.01–1.61 | 0.045 |

| DM | |||

| DM*AP | 1.03 | 0.60–1.75 | 0.92 |

| DM*RFT | 1.44 | 1.02–2.04 | 0.040 |

| CVD | |||

| CVD*AP | 0.98 | 0.70–1.37 | 0.91 |

| CVD*RFT | 0.75 | 0.58–0.98 | 0.035 |

| Allergies | |||

| Allergies*AP | 0.64 | 0.40–1.03 | 0.067 |

| Alllergies*RFT | 1.31 | 0.99–1.73 | 0.054 |

Values are presented as odds-ratio (OR) and confidence intervals (CI 95%). Testing of group differences by *qui-square test. At bold (P) are the relationships between the variables that are significant.

Regarding the number of absent teeth, there was no significant association between the different systemic diseases, habits or gender (p>0.05) (Table 1). Similarly, no significant association was found between the number of residual roots in the different groups (p>0.05) (Table 1).

DiscussionThe total prevalence of AP (2.2%) recorded in this study is in agreement with other European countries.60,9,11 Similar values of RFT (4.2%) were also found in other epidemiological studies, with prevalence's ranging between 1.3% and 4.8%.9,11,15,19,52,53 By contrast, others authors have reported values ranging between 34% and 87%. Differences in health care services and socioeconomically related factors34 may account for this discrepancy (1.3% till 34%)7,9,11,15,19,34,52,54–56 The present results point out that AP is less prevalent in women than in men. Women might be more health conscious and seek dental care more often.9,57 In fact, in the present study women showed less residual roots and more RFT, although not statistically significant.

The higher prevalence of AP in RFT confirms previous observations linking AP to endodontic treated teeth.9,27,49,56,58–61 Paradoxically, in some studies, the prevalence of AP may appear very low and not so closely associated to root filled teeth due to a lower number of remaining teeth, suggesting that those affected by AP may have been extracted, resulting in an unknown proportion of root canal treated teeth being lost to follow-up.1,58

Other considerations, as the quality of root canal treatment, not considered in this study, may also significantly influence the perirradicular status of endodontic treated teeth.62

Despite some limitations of conventional radiography for detection of periapical bone lesions, panoramic radiographs are still used in epidemiological studies.6,7,9,19,63 Moreover, cost-effectiveness of high-resolution Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) images, in clinical routine and research, should be weighed.64 Additionally, the PAI index has been widely used in endodontic literature allowing for comparison with previous studies.6,7,11,19,35,63,65 The reproducibility of the PAI index between the observers has been found.

Present data revealed a statistically significant association between smoking habits and the prevalence of AP and RFT, in agreement with others studies.35,36,66,67 Besides, Krall et al.50 reported a significant dose dependent relationship between the number of cigarettes smoked and the risk of having RFT. In the present study, we couldn’t identify the number of cigarettes smoked being only considered current/former smokers and non-smokers subjects.

Smoking interferes with the wound healing process by affecting the fibroblasts growth, the microvasculature and the immune's system normal functioning48,68 Nicotine has been linked to thicker Streptococcus mutans biofilms, suggesting that smoking can increase the development of caries.69 Socio-economical factors, prevalence of dental caries, regularity of dental care or even association with other systemic conditions35 were not taken into consideration, in the present study. Root canal treatment is only one of the possible options for the treatment of teeth with AP, and we didn’t considerer other therapeutics70–72. However, there was no association with number of absent teeth or prevalence of residual roots with the smoking status.

In the present study a range of cardiac pathologies, like coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension, atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction were included in the CVD group. This was due to the non-specific records of the medical cardiac conditions. Hypertension leads to shortened life expectancy and, if persistent, is an important risk factor for coronary heart disease, stroke or heart failure.73 No statistically significant association was found between AP and CVD (p<0.05). Segura-Egea35 found a significant association between hypertension and AP, but only within smokers. There must be considered some confounding factors in the interpretation of these results. Aleksejuniene et al.’s observations65 suggest that dentists, in some countries, are more radical and prefer to extract teeth with AP in patients displaying cardiovascular problems. Moreover, these individuals may be generally more health concerned and seek dental care more often.

Marotta et al.29 found that AP was significantly more prevalent in teeth of diabetic individuals than in non-diabetic controls. Nevertheless, this only occurred in untreated teeth. Another study showed that worse periapical status correlates with poorer glycemic control levels in diabetic patients.74 On the other hand, Wolle et al.46 showed that the extension of the periapical lesion in type 2 diabetes was similar to that seen in control, non diabetic, animals. Since diabetes is the third most prevalent condition in medically compromised patients seeking dental treatment75, dentists should be aware of the possible relationship between endodontic infections and DM. In the Segura-Egea et al.’s review32 DM was associated with a higher prevalence of AP, greater size of osteolityc lesions, greater likelihood of asymptomatic infections and worse prognosis of RFT. Our study failed to associate a higher prevalence of AP in diabetic patients (p=0.918). Similar to what succeeded with the CVD group, that included a range of cardiac pathologies we were unable to distinguish between type 1, 2 or gestational diabetes.

Fouad43 found a poorer treatment outcome of teeth with pre-operative AP, for diabetic as compared with non-diabetic patients, suggesting that some bacterial species may be more prevalent in necrotic pulps of diabetic than in non-diabetic patients.

Our results, although without association between AP and DM, show that RFT were more prevalent in the DM’ group according to previous data published.76 These patients may be more prone to develop caries77 as wells as severe caries lesions78 with a direct negative effect on dental pulp integrity, specially in non-controlled patients.79

Several risk factors have already been identified80 that can affect the severity, prognosis and the outcome of the endodontic treatment of teeth with AP. Allergies, an immune response to foreign substances, might also be considered an AP’ modifier, through the present results. An interesting and borderline link was found between AP and allergies, however not statistically significant (p=0.067). More studies are required to confirm this association.

In the present investigation the tooth was the unit of study. Many authors refer the same methodology. Furthermore, Lopez-Lopez76 showed similar results when considering the tooth or the individual respecting some systemic conditions

Results of cross-sectional studies should be interpreted with caution, preventing the accurate assessment of which of the endodontically treated teeth recorded as having AP, actually represent a treatment failure or a lesion in a healing process. Other uncontrolled variables, namely the presence of AP pre-operatively and the time elapsed since the respective treatment can introduce bias in the results. Additional studies that provide long-term observations and randomized clinical trials are needed to clarify the prevalence of AP and related risk factors.

ConclusionThe influence of related risk factors over the prognosis of apical periodontitis is a valid tool for the clinician’ treatment decision. The data in the present study suggest an association between some systemic diseases, as CVD, DM, allergies and smoking status with RTF and AP, which must be further explored.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.