The purpose of this study was to evaluate the association between dental caries and body mass index-for-age (BMI-for-age) in a 13-year-old population.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was carried out with a birth-cohort of 181 voluntary 13 year-old adolescents belonging to a grouping of schools in Castelo de Paiva. BMI-for-age, DMFT and oral hygiene habits were recorded. The Z-test, Mann–Whitney and the Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for univariate comparisons. Multivariate association between independent factors and DMFT>0 or DMFT>6 was assessed using backward stepwise binary logistic multivariate regression analysis (0.05 for covariate inclusion and 0.10 for exclusion).

ResultsThe mean DMFT was 4.04 (±2.79) with caries experience affecting 90.1% of adolescents and the majority had normal BMI-for-age (69.1%), 3.3% below normal and 27.6% had weight over normal.

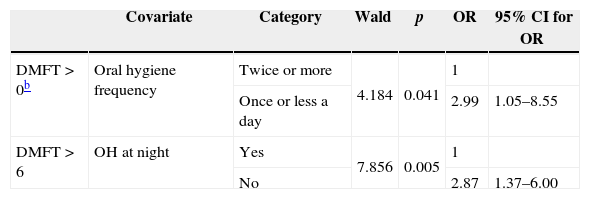

DiscussionNo significant differences were found for DMFT according to gender, school attendance, oral hygiene frequency or BMI-for-age. In multivariate analysis the oral hygiene frequency was shown to be significantly associated with DMFT higher than zero (p=0.041). For a more severe DMFT value (DMFT>6) this frequency was not statistically important, whereas the lack of performing oral hygiene at night showed to be a significant risk factor for severe DMFT (p=0.006). The oral hygiene habits showed to be a better predictor than BMI-for-age for the development of caries disease prediction.

ConclusionThis study confirms that no association could be assigned between BMI-for-age and dental caries in children especially in permanent dentition.

O objetivo deste trabalho foi avaliar a associação entre cárie dentária e índice de Massa Corporal ajustado para idade (IMC-para-idade).

MétodosEstudo transversal populacional realizado em 181 voluntários adolescentes de uma coorte de 13 anos de idade, pertencentes a agrupamentos de escolas em Castelo de Paiva. Foram registados o IMC-para-idade, o CPOD e hábitos de higiene oral. Os testes Z, Mann–Whitney e Kruskal–Wallis foram usados para comparações univariadas. Análise multivariada de fatores associados com CPOD>0 e CPOD>6 foi realizada com análise de regressão multivariada logística bivariada (0,05 para inclusão, 0,10 para exclusão de co-variáveis).

ResultadosO CPOD foi de 4,04 (±2,79), com experiência de cárie que afeta 90,1% dos adolescentes, sendo que a maioria tinha um IMC-para-idade normal (69,1%), 3,3% abaixo do normal e 27,6% tinham peso superior ao normal.

DiscussãoNenhuma diferença significativa foi encontrada para CPOD de acordo com o sexo, a frequência escolar, frequência de higiene bucal ou IMC-para-idade. Na análise multivariada a frequência de higiene oral mostrou-se associada significativamente com CPOD maior que zero (p=0,041). Para um valor de CPOD mais grave (CPOD> 6) esta frequência não foi estatisticamente importante, considerando que a ausência da realização de higiene bucal à noite mostrou ser um fator de risco significativo para CPOD grave (p=0,006). Os hábitos de higiene oral mostraram ser um melhor preditor do que o IMC-para-idade para o desenvolvimento de previsão de doença cárie.

ConclusãoEste estudo confirma que não deverá ser considerada nenhuma associação entre IMC-para-idade e cárie dentária em crianças, especialmente na dentição permanente.

Worldwide there is a growing overweight epidemic among children and teenagers.1–5 In general, the weight of the individuals is measured by means of the body mass index's (BMI). Overweight and obesity are important public health problems, associated with an increased risk for the development of future medical problems such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer and diabetes mellitus.6

Obesity has reached epidemic levels in recent years. The average obesity rate in the European Union is 15.5%, and, even more alarming, the prevalence of overweight children was estimated at 30% in 2006.7

Data on the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Portuguese children and adolescents (10–18 years old, Madeira region, and 7–14 years old, Mafra, respectively) using the CDC criteria reveal that the prevalence of overweight was between 8.3% and 16% for males and 18.9% and 35% for females, and the prevalence of obesity varied between 15% and 26% for males, and 12.2% and 20% for females.8,9

Some studies3,10 show that the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children increased in magnitude from two to five times in developed countries and up to almost four times in developing countries.

Theoretically, overweight and obesity can be associated with dental caries, through a greater availability of cariogenic factors, modulated by oral hygiene habits. Given the causal relation between refined carbohydrates and dental caries, it is appropriate to hypothesize that overweight might also be a marker for dental caries in children and teenagers.11–17

While the consequences of obesity will have an indirect effect on oral conditions, this alone is no justification for the disease.18 Dental caries and obesity are both multifactorial conditions with a complex aetiology and are associated with such factors as dietary habits and available nutrients, oral hygiene or saliva. A sugar-rich diet, including beverages, is associated with various health problems such as obesity and dental caries. Although the eating pattern among overweight and obese children may represent a risk of dental caries, documentation is scarce, and a systematic review has revealed contradictory results, mainly in paediatric populations5,12,16,19

Two studies conclude that overweight and obese adolescents had more caries than normal-weight individuals,16,20 a third one14 concluded that only on 12-year-old children caries was associated with BMI increase, and another21 found this association only in primary dentition. A recent study22 found, for the first time, a relationship between dental caries prevalence and body fat percentage measured by DXA and attributed this to a misclassified adiposity status of the paediatric population evaluated by BMI compared to Dual energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA).

Obesity alone was not a good predictor of dental decay, the combination between earlier obesity and caries experience being even better for the prediction of caries in permanent second molars than in the permanent first molars.23 An inverse association between caries and subsequent changes in BMI was found only among children with well-educated mothers, suggesting that high caries experience may be a marker for low future risk of overweight among the more advantaged.5

One study reports an association of high BMI and low caries in primary dentition,24 and other studies report no association between BMI and dental caries.11,24–30

The present study intends to evaluate whether there is an association between dental caries and BMI-for-age in a 13-year-old children population (HØ: Dental caries is independent of BMI).

Materials and methodsBMI evaluation in children and teenagers must account for growth and gender-specific differences as compared to adults. Child-specific BMI values are usually referred to as “BMI-for-age”.31 According to the Guidelines of Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) children are considered overweight if they are between the 85th to less than the 95th percentile of age and gender-related BMI and are considered obese if they are at or beyond the 95th percentile of age and gender-related BMI.32

A cross-sectional study was carried out with a birth-cohort of 181 voluntary 13 year-old adolescents (91% participation), belonging to the same school group (Castelo de Paiva) that cover a predominantly rural zone – Pejão and Sobrado – with some urban characteristics. The non-examined 9% were due to student school-transfer to another region or due to being home sick during the scheduled days for the clinical observations. Besides sex, date of birth and school group, anthropometric measures (weight and height) and clinical oral indicators (frequency and moments of daily oral hygiene, decayed (DT), missing (MS) and filled (FT) teeth) were registered according to the WHO criteria.33–35

Decayed, missing and filled teeth were summed, resulting in the DMFT index, and two categorizations for this variable were made: DMFT>0 and, for a more severe DMFT value, DMFT>6.

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS© vs.20.0. Counts and proportions were reported for categorical variables (Tables 1 and 2) and comparisons among those (dichotomised variables) were performed with a Z-test. DMFT data (Table 3) were described as mean values and standard deviation, and as median values and corresponding 25th and 75th percentiles (non-normally distributed variable) and minimum and maximum values. A significance level of 0.05 was considered for inferential procedures. The comparison of the median DMFT index (Table 3) by gender, schools and moment of oral hygiene was performed using the Mann–Whitney test, while the comparison by oral hygiene frequency and BMI-for-age was performed using the Kruskal–Wallis (as the assumption of normality of the DMFT distribution does not hold). Multivariate associations between DMFT higher than zero or higher than six (Table 4) were assessed using backward stepwise binary logistic multivariate regression analysis (0.05 for covariate inclusion and 0.10 for exclusion).

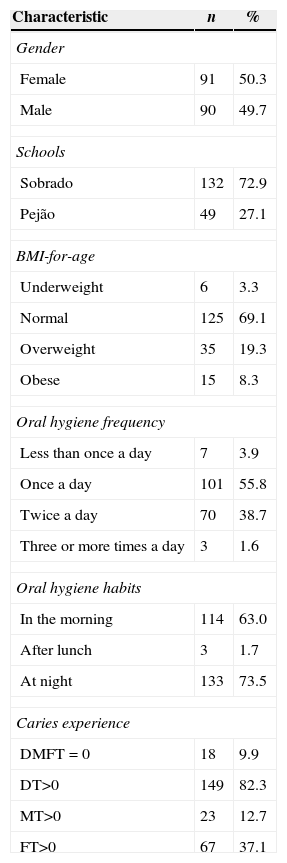

Distribution of sociodemographic and clinic characteristics of subjects.

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 91 | 50.3 |

| Male | 90 | 49.7 |

| Schools | ||

| Sobrado | 132 | 72.9 |

| Pejão | 49 | 27.1 |

| BMI-for-age | ||

| Underweight | 6 | 3.3 |

| Normal | 125 | 69.1 |

| Overweight | 35 | 19.3 |

| Obese | 15 | 8.3 |

| Oral hygiene frequency | ||

| Less than once a day | 7 | 3.9 |

| Once a day | 101 | 55.8 |

| Twice a day | 70 | 38.7 |

| Three or more times a day | 3 | 1.6 |

| Oral hygiene habits | ||

| In the morning | 114 | 63.0 |

| After lunch | 3 | 1.7 |

| At night | 133 | 73.5 |

| Caries experience | ||

| DMFT=0 | 18 | 9.9 |

| DT>0 | 149 | 82.3 |

| MT>0 | 23 | 12.7 |

| FT>0 | 67 | 37.1 |

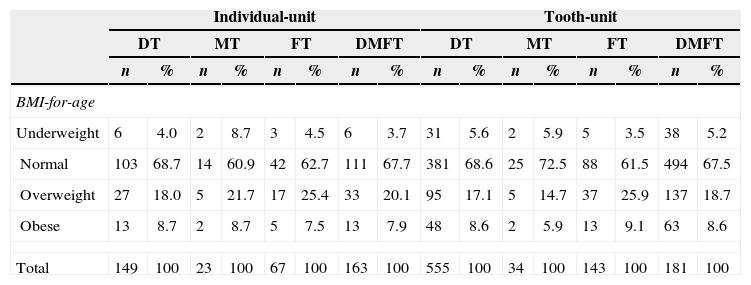

Distribution of caries experience (decayed, missing and filled tooth, and DMFT index) by BMI-for-age classes for individual-unit and tooth-unit.

| Individual-unit | Tooth-unit | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DT | MT | FT | DMFT | DT | MT | FT | DMFT | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| BMI-for-age | ||||||||||||||||

| Underweight | 6 | 4.0 | 2 | 8.7 | 3 | 4.5 | 6 | 3.7 | 31 | 5.6 | 2 | 5.9 | 5 | 3.5 | 38 | 5.2 |

| Normal | 103 | 68.7 | 14 | 60.9 | 42 | 62.7 | 111 | 67.7 | 381 | 68.6 | 25 | 72.5 | 88 | 61.5 | 494 | 67.5 |

| Overweight | 27 | 18.0 | 5 | 21.7 | 17 | 25.4 | 33 | 20.1 | 95 | 17.1 | 5 | 14.7 | 37 | 25.9 | 137 | 18.7 |

| Obese | 13 | 8.7 | 2 | 8.7 | 5 | 7.5 | 13 | 7.9 | 48 | 8.6 | 2 | 5.9 | 13 | 9.1 | 63 | 8.6 |

| Total | 149 | 100 | 23 | 100 | 67 | 100 | 163 | 100 | 555 | 100 | 34 | 100 | 143 | 100 | 181 | 100 |

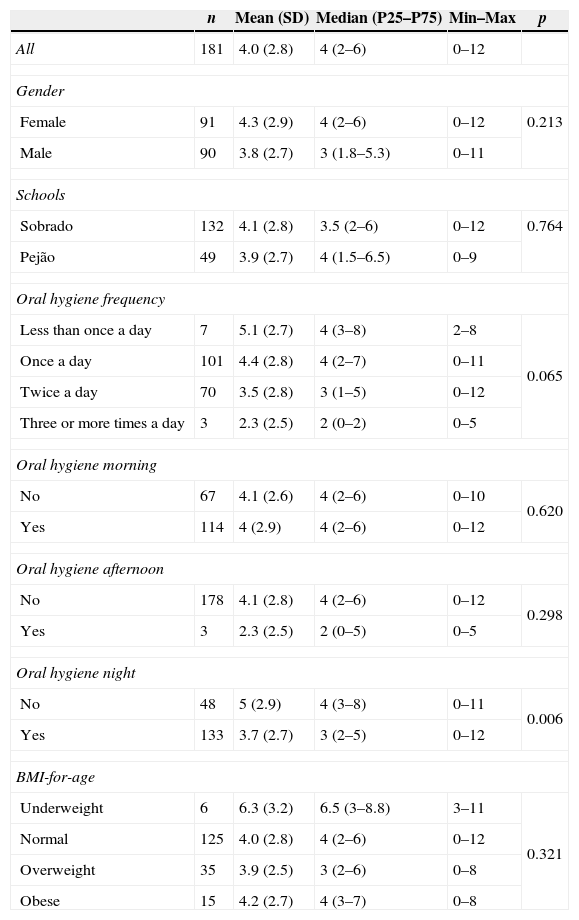

DMFT distribution according to several variables.

| n | Mean (SD) | Median (P25–P75) | Min–Max | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 181 | 4.0 (2.8) | 4 (2–6) | 0–12 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 91 | 4.3 (2.9) | 4 (2–6) | 0–12 | 0.213 |

| Male | 90 | 3.8 (2.7) | 3 (1.8–5.3) | 0–11 | |

| Schools | |||||

| Sobrado | 132 | 4.1 (2.8) | 3.5 (2–6) | 0–12 | 0.764 |

| Pejão | 49 | 3.9 (2.7) | 4 (1.5–6.5) | 0–9 | |

| Oral hygiene frequency | |||||

| Less than once a day | 7 | 5.1 (2.7) | 4 (3–8) | 2–8 | 0.065 |

| Once a day | 101 | 4.4 (2.8) | 4 (2–7) | 0–11 | |

| Twice a day | 70 | 3.5 (2.8) | 3 (1–5) | 0–12 | |

| Three or more times a day | 3 | 2.3 (2.5) | 2 (0–2) | 0–5 | |

| Oral hygiene morning | |||||

| No | 67 | 4.1 (2.6) | 4 (2–6) | 0–10 | 0.620 |

| Yes | 114 | 4 (2.9) | 4 (2–6) | 0–12 | |

| Oral hygiene afternoon | |||||

| No | 178 | 4.1 (2.8) | 4 (2–6) | 0–12 | 0.298 |

| Yes | 3 | 2.3 (2.5) | 2 (0–5) | 0–5 | |

| Oral hygiene night | |||||

| No | 48 | 5 (2.9) | 4 (3–8) | 0–11 | 0.006 |

| Yes | 133 | 3.7 (2.7) | 3 (2–5) | 0–12 | |

| BMI-for-age | |||||

| Underweight | 6 | 6.3 (3.2) | 6.5 (3–8.8) | 3–11 | 0.321 |

| Normal | 125 | 4.0 (2.8) | 4 (2–6) | 0–12 | |

| Overweight | 35 | 3.9 (2.5) | 3 (2–6) | 0–8 | |

| Obese | 15 | 4.2 (2.7) | 4 (3–7) | 0–8 | |

Multivariate analysisa: statistical significant independent factors associated with DMFT>0 and DMFT>6.

| Covariate | Category | Wald | p | OR | 95% CI for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMFT>0b | Oral hygiene frequency | Twice or more | 4.184 | 0.041 | 1 | |

| Once or less a day | 2.99 | 1.05–8.55 | ||||

| DMFT>6 | OH at night | Yes | 7.856 | 0.005 | 1 | |

| No | 2.87 | 1.37–6.00 |

Variables entering the first step of both models: schools (Sobrado vs Pejão), sex (female vs male), oral hygiene frequency (twice or more vs once or less a day), oral hygiene in the morning (yes vs no) oral hygiene at night (yes vs no), and BMI (underweight, normal, at risk of overweight, overweight).

The inherent ethical procedures for the study were approved and safeguarded all principles of the Helsinki Declaration, and the study was part of the normal activities of the Primary Health Centre at school health education. All participants were informed about the study and their legal representatives signed an informed consent.

ResultsThere were a small majority of female participants (50.3%) (Table 1). The mean (SD) DMFT was 4.04 (2.79), with a range between 0 and 12 teeth affected, 90.1% of the youths had experienced caries disease with a high rate of untreated disease. The majority of individuals in this sample had normal BMI-for-age (69.1%), 3.3% below normal and 27.6% presented weight above normal.

As to oral hygiene habits, 108 individuals (59.7%) reported to brush their teeth once a day or less, a significantly higher percentage when compared with those who had more frequent habits (twice or more) (Z-test, p=0.012).

Only 9.9% of the sample presented a zero value for DMFT (Table 2), with decayed teeth being a very high proportion of cases contributing to the DMFT value. The distribution and severity of the DMFT by BMI-for-age classes are represented in Table 2 for both individual-unit and tooth-unit registration levels.

No significant differences were found for DMFT according to gender, school, oral hygiene frequency, oral hygiene in the morning or in the afternoon, or BMI-for-age (Table 3). Those who execute oral hygiene in the evening (at night) have significantly smaller DMFT (Mann–Whitney test, p=0.006). However, in a multivariate analysis (Table 4), the oral hygiene frequency showed to be significantly associated with DMFT higher than zero, while for a more severe DMFT value, DMFT higher than 6, this frequency was not significant, whereas the lack of the habit of performing oral hygiene at night showed to be significantly associated and constituted a risk factor for severe DMFT.

DiscussionAlthough overweight and oral health are globally leading health problems, particularly in children and adolescents, the research into the relationship between obesity and the frequency of caries in Portuguese children has been neglected; however, obesity and oral diseases share many common risk factors.

We believe this was one of the first studies that could provide data on the relationship between the nutritional status and oral health among Portuguese school children.

The aim of this study was to evaluate as well as to evaluate if there is an association between dental caries and BMI-for-age in 13-year-old Portuguese children. The main finding in the present study was the absence of association between DMFT and BMI-for-age, and the cross-sectional characteristics of this study do not allow an evaluation of causal relationship between factors.

In this group dental caries was a highly prevalent disease. Most adolescents had normal BMI; however, about 27.6% had an excess of body fat related to lean mass (19.3% overweight and 8.3% obese). This observation is consistent with other studies.8,11–13,24–28

The relationship between adolescent obesity and dental caries was not statistically significant, and this is similar with other studies11,24–30 whereas the oral hygiene habits had more statistical importance in this relation between BMI-for-age and DMFT, so the conflicting results published over time, may in part be conditioned by the frequency and time of execution of daily oral hygiene habits.

DMFT did not differ significantly between schools (p=0.764; Table 3), assuming a similar group of nutritional characteristics for teenagers in the region.

In relation to the distribution of severity of the DMFT along BMI-for-age classes, the low number of cases in extreme quartiles may make it difficult to find any correlation, and this is also valid for any independent component of DMFT.

These results are in accordance with previous findings in other studies11,24–30 in different populations were no association, between obesity and dental caries was found in the permanent dentition. Our analyses provide no evidence to suggest that overweight 13-year-old children are at increased risk for dental caries.

These findings could be surprising assuming that overweight should be associated with dental caries, as obesity and caries are, in principle, influenced by similar factors.

A possible limitation of the study was that the pubertal developmental stage (13 years-old) of adolescents was not evaluated, assuming the evidence36 that childhood obesity could induce to a precocious puberty.

Other studies will be needed, mainly prospective studies and with other groups at different ages. Although appropriate health policies should be established, with a transdisciplinary perspective to minimize the impact of these two pathological conditions affecting young teenagers, preventive programmes must be developed including effective strategies for nutrition control in order to avoid obesity as well as dental caries.

ConclusionThere was no significant difference in the DMFT for the 4 BMI-for-age classes in this population, therefore no association between dental caries and body mass index-for-age in this 13-year-old population group.

The oral hygiene habits are a better predictor than BMI-for-age for the presence of caries disease.

These findings confirm that no association could be assigned between BMI-for-age and dental caries so further investigation could be important to address what factors specific to overweight in children might be protective against dental caries especially in permanent dentition.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of people and animalsThe authors state that the procedures followed were in accordance with regulations established by the management of the Clinical and Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and written consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The author MC Manso thanks the financing of EU funds (ERDF, through the COMPETE) and national funds (Foundation for Science and Technology) by the project Pest-C/EQB/LA0006/2013.