Vascular anomalies are disorders of the endothelium and related tissue resulting in an aberrant and hamartomatous vessel growth. They are divided into vascular tumors (including haemangioma) and vascular malformations. Additionally some vascular anomalies can be acquired such as venous lakes or varix. Different modalities to treat them are available including laser therapy, steroid therapy, embolization, β-blockers therapy, sclerosant therapy, surgery or cryosurgery. This article reports the usefulness of CO2 laser and diode laser for the treatment of vascular anomalies of the oral cavity and concluded that laser is a suitable tool for the treatment of these lesions and delivers very efficient results without significant complications such as hemorrhage, pain, infection, and significant scarring.

As anomalias vasculares são alterações do endotélio e do tecido adjacente, resultando num crescimento vascular aberrante e hamartomatoso. São divididas em tumores vasculares (incluindo o hemangioma) e malformações vasculares. Adicionalmente algumas anomalias vasculares podem ser adquiridas, como os lagos venosos ou varizes. Diferentes modalidades estão disponíveis para o seu tratamento, incluindo o laser, esteróides, embolização, β-bloqueadores, esclerosantes, cirurgia ou criocirurgia. Este artigo apresenta a utilidade do laser de CO2 e do laser de diodo para o tratamento de anomalias vasculares da cavidade oral e conclui que o laser é um instrumento adequado para o tratamento destas lesões e proporciona resultados muito eficientes, sem complicações significativas como hemorragia, dor, infeção, ou cicatrizes excessivas.

Vascular anomalies are disorders of the endothelium and related tissue resulting in an aberrant and hamartomatous vessel growth.1 A number of terms have been used to describe them such as angiomas, haemangioma, vascular birthmarks but they are now divided into vascular tumors (including haemangioma) and vascular malformations.2 Additionally some vascular anomalies can be acquired such as venous lakes or varix.3

Haemangioma are the most common tumors of the infancy, occurring in 4–12% of all children.1,4 They are rarely seen at birth, but they appear after a few weeks of life, showing a proliferative phase quicker than the physical growth. Before the first years of life they slow in growth and begin the involution phase. Multifocal haemangioma can be component of PHACES syndrome (Posterior fossa brain anomalies; Haemangioma usually in cervical segment haemangioma; Arterial anomalies; Cardiac defects and coarctation of the aorta; Eye anomalies; Sterna cleft).5

Vascular malformations are classified according to the type of involved vessels such as capillary, venous, lymphatic and arteriovenous malformations. Progressive ectasia of existing vascular structures caused by sepsis, intercurrent trauma, pregnancy or puberty results in the expansion of vascular malformations. The main characteristic feature of vascular malformations is that they never show signs of involution. Vascular malformations can be categorized also according to their hemodynamic features in low flow lesions including capillary, venous and lymphatic malformations and high-flow lesions including arterial, arteriovenous malformations and arteriovenous fistulas.1 Some vascular malformations may be associated with syndromes such as Sturge–Weber syndrome, blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome or Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome.1

Varix and venous lakes are common vascular lesions caused by focal dilatation of venules, occurring more often in elderly patients. The most common oral site is the lip. Once formed they persist throughout life.3,6

Esthetic problems, hemorrhaging episodes or impairment of oral normal functions are the main reasons for the treatment of vascular anomalies. Many different treatment modalities are available including laser therapy, steroid therapy, embolization, β-blockers therapy, sclerosant therapy, surgery or cryosurgery.1,7,8

Laser therapy is a mainstay of management of mucosal and skin vascular malformations nowadays with different wavelengths, different irradiation parameters and application procedures.2,9 They can be used in photocoagulation, vaporization or excision procedures. The most used lasers are neodymium–yttrium–aluminum–garnet (Nd:YAG) laser (1064nm), potassium–titanium–phosphate (KTP) laser (532nm), diode laser (800–980nm), pulsed dye lasers (585 and 595nm), argon laser (514nm) and carbon dioxide (CO2) laser (10,600nm).1,2,10–13 They have been found to be safe and effective in the treatment of vascular anomalies.2,6,7,10,11

Our aim is to present two case reports of oral vascular anomalies showing the usefulness of laser for the treatment of these lesions.

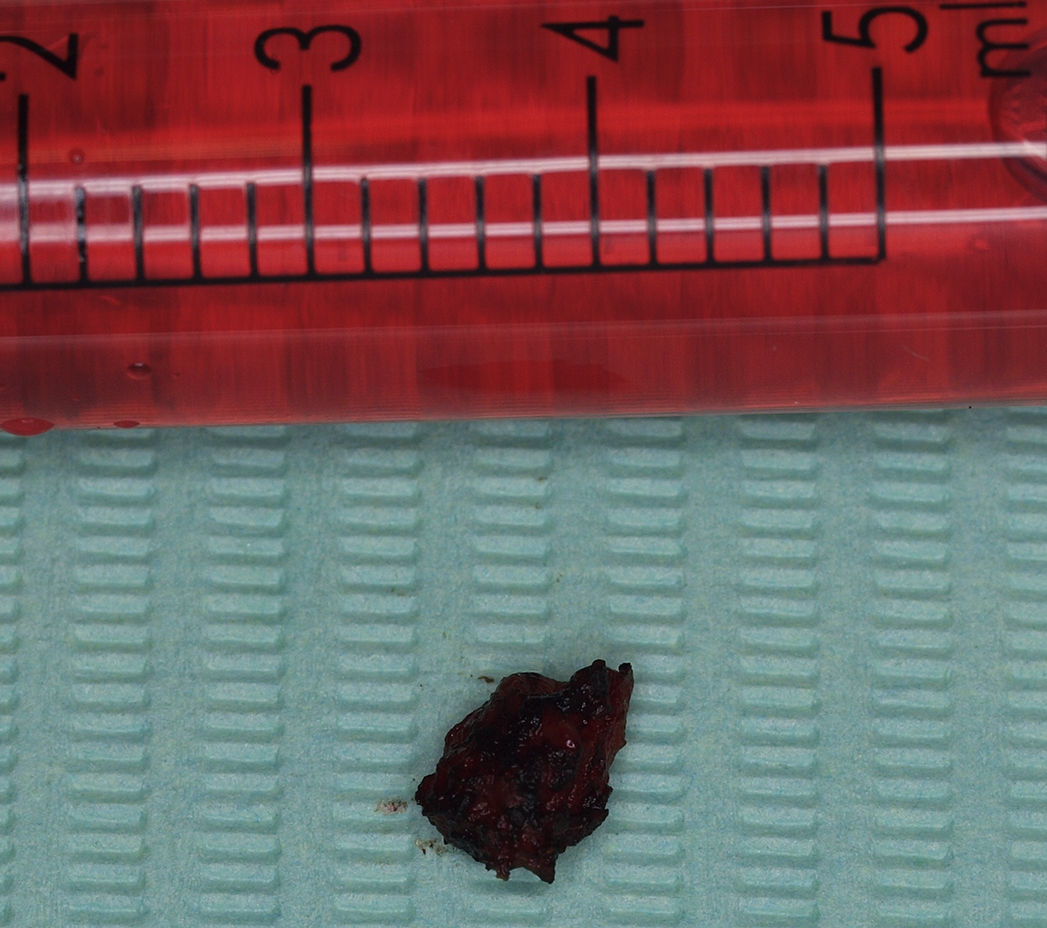

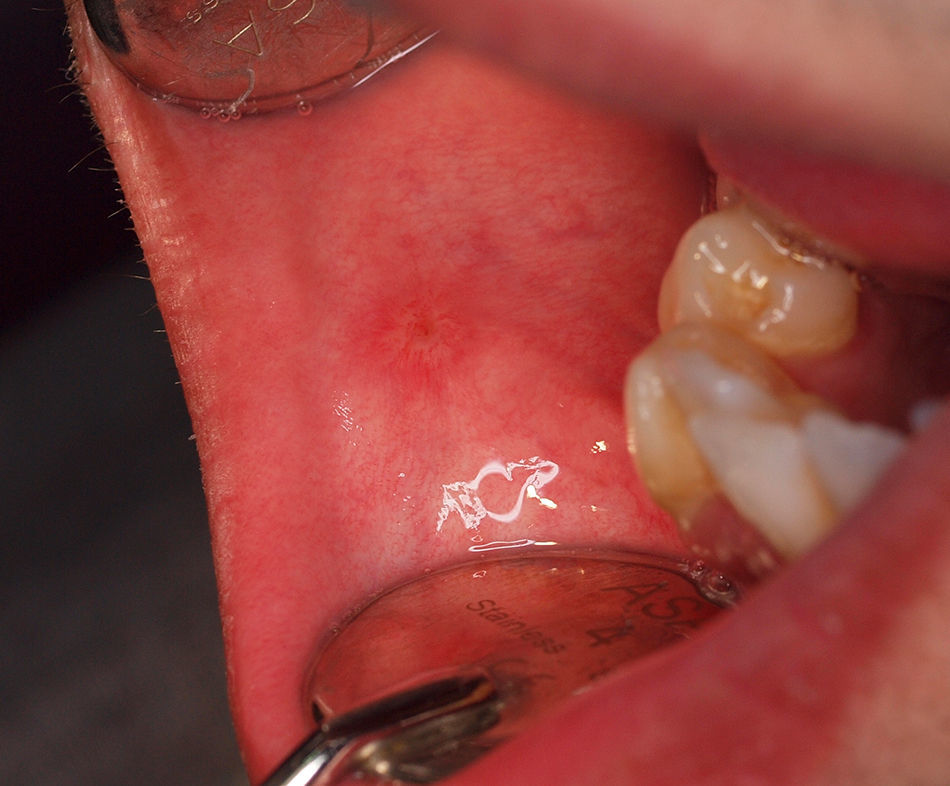

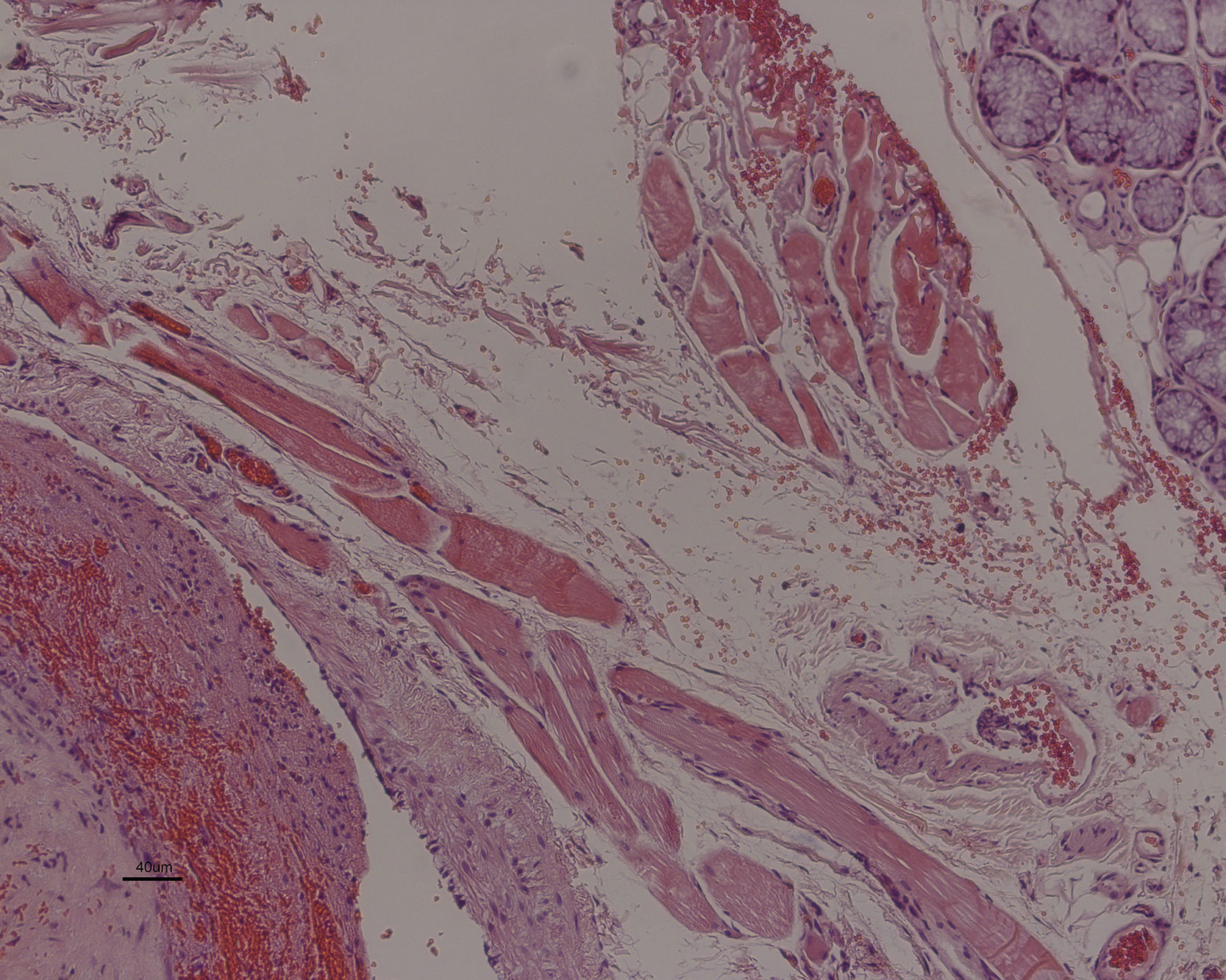

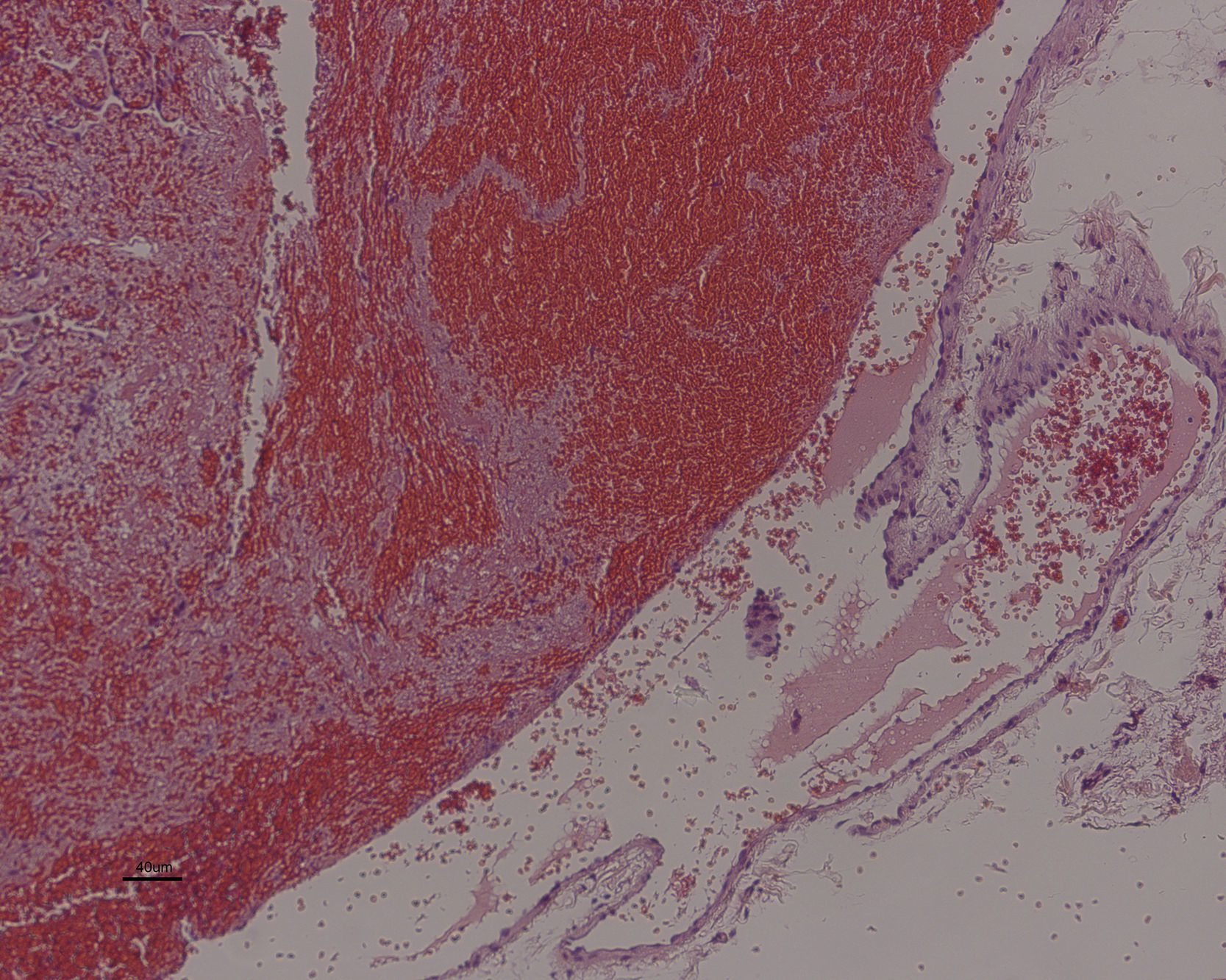

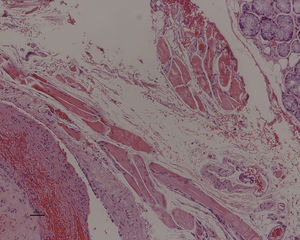

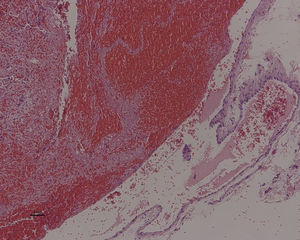

Case descriptionCase 1An 18-year-old man was referred to our department for evaluation of an oral bluish lesion. He referred having this lesion since a very young age with some periods of transient enlargement in the recent years. This nodule caused discomfort especially during mastication with history of trauma. Clinical examination revealed a blue colored papule measuring 1.5cm×1cm, on the anterior right buccal mucosa (Fig. 1). At palpation, the papule felt soft, cold, without pulse and blanch with diascopic maneuver. Complete blood count and general biochemistry were within normal values. Clinically we diagnosed this lesion as a vascular malformation. Excision of the lesion was performed under local anesthesia using a CO2 laser (DEKA™ Smart US20D, Firenze, Italy), focalizing the beam for mucosal cut, on a pulse mode (50Hz), 4.5W output power, 1mm spot, power density (PD) 573.25W/cm2, fluence 11.46J/cm2, defocalizing for tissue coagulation on a continues mode, 7W output power, 2mm spot, PD 222.93W/cm2 and fluence 222.93J/cm2 (Fig. 2). Usual safety precautions for the operator, patient, and assistant were followed. The wound was allowed to repair by second intention. Excised tissue (Fig. 3) was submitted to routine histological examination with indication of a CO2 laser excision. Paracetamol 1g at 12h interval during 3 days was prescribed. After 3 weeks, wound healing was completed uneventfully (Fig. 4). He did not report any post-operatory complication such as pain or edema. On histopathology report the lesion was compatible with venous malformation (Figs. 5 and 6). The patient was seen 1 month and one year after and was free of recurrence.

A 52-year-old man was referred to our department for evaluation of a bluish blister on the lip with three years of evolution. This papule caused labial discomfort and esthetic problems. He had arterial hypertension and was medicated with captopril 25mg. Clinical examination revealed a dark blue colored papule measuring 0.5cm×1cm, in the lower lip (Fig. 7). On palpation, the papule was soft and blanch with diascopic maneuver. Clinically we diagnosed this lesion as an acquired vascular lesion (venous lake). Under local anesthesia we performed a photocoagulation of the lesion using a diode laser 975nm (LaserHF™, Hager & Werken, Duisburg, Germany) in non-contact mode (2mm of focal distance) with a 350μm fiber, continues mode, 3W power, during 10seconds with a fluence of 20J/cm2 (Figs. 8 and 9). Usual safety precautions of the operator, patient, and assistant were followed. The wound was allowed to repair by second intention. Paracetamol 1g at 12h interval during 3 days was prescribed. After 2 weeks, wound healing was completed uneventfully (Fig. 10). He did not report any post-operatory complications such as pain or edema. The patient was seen 1 month and one year after and was free of recurrence.

The first anatomic-pathological classification of vascular lesions was developed by Virchow,14 classifying vascular tumor into angiomas and lymphangiomas, which were then characterized as simplex, cavernosum and racemosum. In 1982, Mulliken and Glowacki15 clarified the field of vascular anomalies by categorizing these lesions based on their clinical behavior and cellular kinetics in haemangioma and vascular malformations. Nowadays, they are divided into vascular tumors (including infantile haemangioma and congenital haemangioma) and vascular malformations (including capillary, lymphatic, venous, arterial and combined malformations).2 Acquired vascular anomalies include venous lakes or varix.3,6 In the present work, history and clinical characteristics favored the diagnosis of small vascular anomalies, a venous malformation in the first case and venous lake in the second case.

In the cases of large vascular lesions, warm, with palpable thrill or of uncertain diagnosis imagiologic studies are routinely indicated. Doppler ultrasound or angiography may show the type and density of the vessels.16 Magnetic resonance or computed tomography is useful to delineate the extent of a lesion prior to any surgery.1

Although many different treatment modalities have been used in vascular anomalies the use of high-power lasers is considered one of the greatest technologies advances in this field.7,8,12 This is related with the laser advantages such as elimination of vascular lesion without significant hemorrhage, disinfection of the surgical wound, no need for sutures, less scaring, and less post-operative complications in comparison with conventional surgery.12,17 We used two different lasers: CO2 and diode laser. CO2 laser emits energy with a 10.6μm wavelength in the infrared zone that is absorbed by water. The high water content of the oral soft tissues makes this laser one of the most used in oral soft tissue surgery with high precision cut and excellent haemostasis.17 However, it only coagulates vessels smaller than 0.5mm diameters. In well-circumscribed and small low-flow vascular malformation CO2 laser has been used successfully as seen in the first case of an excision procedure.10 The diode laser (800–980nm) is poorly absorbed in water and selectively absorbed by hemoglobin. As result this laser penetrates deeply in the tissue (4–5nm) and emits heat in contact with hemoglobin in blood vessels causing coagulation tissue deeper than 7–10nm, in a process designated by photocoagulation. These characteristics make this laser ideal for the photocoagulation technique as a non-invasive procedure.1,7 The disadvantage of this technique comparing to CO2 laser excision is the lack of specimen for histopathological report. However, as we observed in the second case, small and low-flow venous anomalies can be successfully and easily treated by photocoagulation. Azevedo et al.6 treated effectively 17 venous lakes of the lip with photocoagulation using diode laser without complications. This happened also in our cases. Pain, scarring, hemorrhage and edema were not observed in our cases and complete cicatrisation was observed in approximately 2–3 weeks.

In conclusion, vascular venous anomalies of small dimensions can easily be treated with CO2 laser excision or diode laser photocoagulation. Laser is a suitable tool for the treatment of vascular malformations of the oral cavity and delivers very efficient results without complications such hemorrhage, pain, infection, and significant scarring.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.