Mandibular fractures in children are relatively rare, not only by their anatomical and physiological aspects, but also by their social factor, which makes this group less exposed to high-impact trauma. Thus, the specific pediatric treatment, through a minimally invasive approach should also be established, avoiding future functional disorders. In our case, a female patient, a 3-year-old accident victim was affected by a domestic symphysis fracture and bilateral mandibular condyle. Surgical treatment of fractures of the mandibular symphysis was performed two days after the trauma, under general anesthesia for reduction and fixation, employing a 1.5 titanium plate system in the midline of the mandibular symphysis. The condylar fractures were treated conservatively, immediately using gruel and oral therapy to avoid complications such as temporomandibular joint ankylosis. The patient has been followed up by our staff and has no restriction in mandibular movements and no limitation of mouth opening.

Fraturas mandibulares em crianças são relativamente raras, não apenas por seus aspectos anatômicos e fisiológicos, mas pelo fator social, o que torna este grupo menos exposto ao trauma de alto impacto. Assim sendo, o tratamento pediátrico específico, por meio de uma abordagem minimamente invasiva também deve ser instituído, evitando futuros transtornos funcionais. Neste caso, uma criança com idade menor que 3 anos, vítima de acidente doméstico sofreu trauma em face resultando em fratura sinfisária e em côndilo mandibular bilateralmente. O tratamento precoce foi instituído sob anestesia geral para a redução e fixação, empregando um sistema de placa de titânio 1.5 em sínfise mandibular. Fraturas condilares foram tratadas conservadoramente, por meio de dieta líquido/pastosa e fisioterapia, para evitar complicações como a anquilose da articulação temporomandibular. A paciente está em acompanhamento pela equipe e não apresenta restrição nos movimentos mandibulares e nem limitação de abertura bucal.

Pediatric fractures are unusual when compared with fractures in adults. The reasons for this statement are based primarily on social and anatomical factors. Most often children are in protected environments, under the supervision of parents and thus less exposed to major trauma, occupational accidents or interpersonal violence, which are common causes of facial fractures in adults.1 Regarding maxillofacial fractures, a low incidence is due to the early stage of development of the facial skeleton and of the sinuses, leading to a craniofacial disproportion. The flexibility of the facial skeleton and the relative protection offered by existing fat in the subcutaneous tissue around the bones of the face also contribute to reduce the incidence of fractures, especially maxillofacial fractures.2,3

Approximately half of all pediatric facial fractures involve the mandible4 and boys are more commonly affected than girls by a ratio of 2:1 and the majority of injuries occur in teenagers.5

Although much of the relevant technology is shared, management of pediatric mandible fractures is substantially different from that of the adult injury. This is due primarily to the presence of multiple tooth buds throughout the substance of the mandible, as well as to the potential injury to future growth. Although these issues complicate the management of pediatric mandible fractures, these younger patients also have the potential for restitutional remodeling, as opposed to the sclerotic, and functional remodeling seen in adults. All of this must be taken into consideration during the evaluation of and approach to these injuries.6–8

An understanding of the surgical or treatment options is essential for making informed choices to best manage these injuries. This paper describes a case of a pediatric mandibular fracture where a conservative treatment was performed in the bilateral condyles and a rigid internal fixation was done in the region of the mandibular symphysis.9

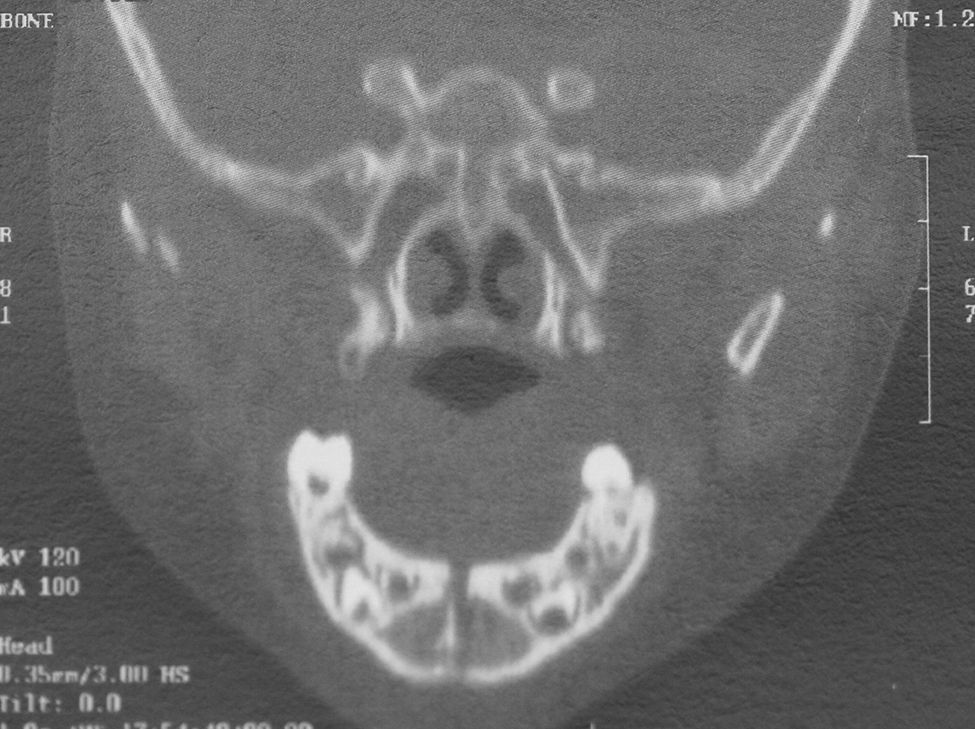

Case reportA 3-year-old was the victim of a domestic accident not suffered from a fall (Fig. 1). The mother reported no syncope, vomiting or drowsiness by the child, after discarding the neurological examination of suspected head trauma associated with brain injury. On physical examination there was local presence of the lower lip laceration, avulsion of the lateral incisor and upper right canine, extrusive luxation of the maxillary central incisors, lateral dislocation of the first molars and right and left vestibular wall bone fracture in the anterior maxilla. In addition, the child had swelling and bruising in the submentual region and mouth floor. By radiography, a bone fracture was found in the region of the mandibular symphysis and bilateral mandibular condyle fracture, confirmed by physical examination (Figs. 2 and 3).

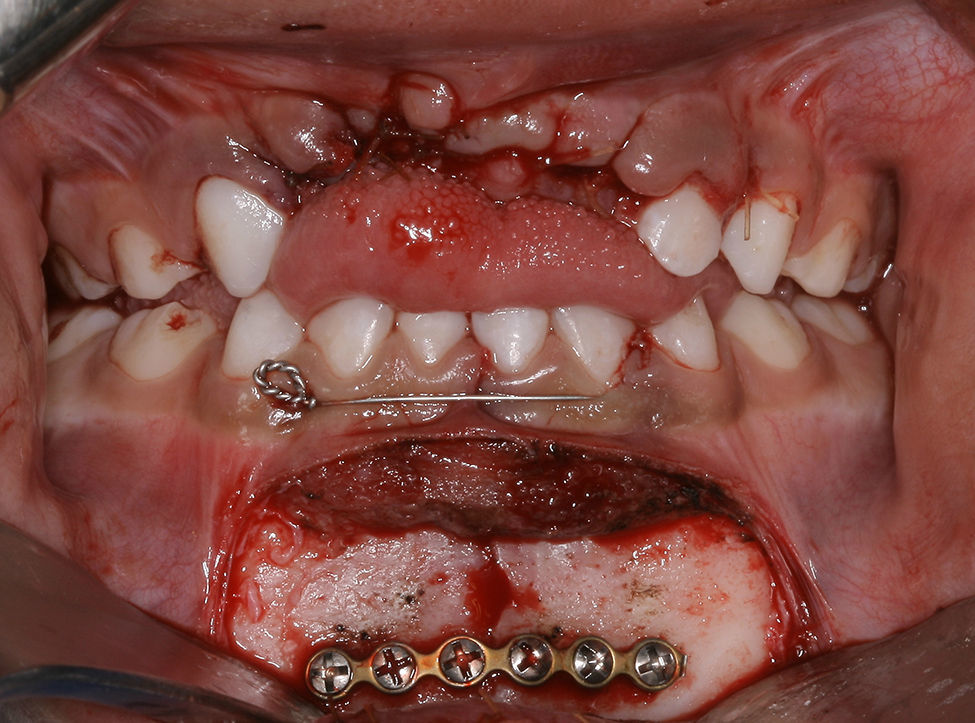

The immediate action was the suture of the lower lip and containment of the lower teeth with wire aciflex (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson Medical, Brazil) and composite resin from the right canine to the left (Fig. 4). To perform the symphysis treatment in this case, we used a rigid internal fixation (Fig. 5). However, because there is a need for minimal invasiveness, we recommended “minimally invasive” internal fixation (MIIF) where a maximum fixation becomes as important as the lowest possible level of injury. The definitive treatment was instituted surgery under general anesthesia, 36h after facial trauma to reduce the mandibular symphysis fracture with a 1.5 titanium plate system (Neortho, Curitiba, Brazil) (Fig. 6). Conservative treatment associated with immediate therapy was chosen for the left and right condylar fractures.

In the post-operative CT scan, we found that a fracture reduction did not satisfactorily occur; however, in the 6 month follow-up, the minimally invasive treatment had proven quite effective, restoring masticatory function and allowing a satisfactory mouth opening (Figs. 7–9). A follow up was done every 6 months.

DiscussionFacial fractures in the pediatric age group generally account for about 5% of all fractures and this percentage drops considerably in those less than the age of 5. Their incidence rises as children begin school and also peaks during puberty and adolescence. A male dominance exists in all age groups.9 Haug and Foss 2000 report that less than 1% of all fractures occur in patients younger than 5 years and 1–14.7% in patients younger than 16 years.10

After the age of 5–7 years, rapid progression of neuromotor development results in a general desire for independent activity, more frequent social interactions with other children, and a wider range of activities outside of the house, with less stringent parental and adult supervision. These factors result in increased opportunity for direct facial trauma. In the study of Atilgan et al. 2010,11 falls were the most common cause of maxillofacial injuries in young patients, and the second most common cause was road traffic accidents. However, studies from other parts of the world have reported that road traffic accidents were the leading cause of facial fractures in young adult patients.12 In our case, the reason for the pediatric trauma was a domestic accident not related to a fall.

For treatment of these accidents, Davison et al. 200112 said that the risks of facial growth disturbance in the ORIF has not been supported. In contrast, no treatment in unrecognized mandibular fractures leads to a high incidence of orthognathic surgery and craniofacial treatment. The potential damage to tooth roots and follicles can be minimized with a careful technique, which places bicortical screws in the lower mandibular border with monocortical screws placed in the more superior plates. Zimmerman et al. 200613 said that open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) provides stable three-dimensional reconstruction, promotes primary bone healing, shortens treatment time and eliminates the need for or permits early release of maxillomandibular fixation (MMF).

As reported in the surgical technique, the principles of our open treatment of symphysis were those of a minimally invasive rigid internal fixation by means of plate and screws in the monocortical mandibular, much like Cole et al. 2009.14 Posnick 1994, also corroborates with the conduct and then adds that it does not recommend placing signs in the area of tension.15 Unlike Cole, the plate was placed on the system with 1.5mm screws plus four 3.5mm screws. No work exists in the literature comparing the two fastening systems mentioned above, used in pediatric fractures in children younger than 5 years old; however, we believe the choice of a minimally invasive fixation should always be recommended to treat children younger than 5 years of age, whereas we obtained with this system of fixing, the same success reported by other authors, specifically in this type of fracture. This metallic osteosynthesis system is looked on as the ‘gold standard’. However, this metallic system has an important disadvantage; in all cases, plate and screw removal is recommended, particularly in young children, such as in this case. If not removed, Bos 2005,16 reported that the metal implants may cause stress shielding with local osteoporosis and possible re-fracture after removal. Removal is recommended for all young patients.

The usual recommended treatment of fractures of the mandibular condyle has been conservative, with re-establishment of normal occlusion with or without maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) followed by physiotherapy.12 To observe late clinical changes in patients treated with the closed method, there are those that indicate the open method in certain cases with direct exploration of the site of fracture reduction and osteosynthesis.1 In the closed treatment, a short period of MMF, for no more than 7–10 days, is observed. MMF is usually followed by a period of physical therapy consisting of mandibular opening exercises guided by elastics to promote remodeling of the condylar stump and prevent ankylosis.15,17

Although open reduction of condylar fractures avoids MMF and may improve the functional outcome, most authors recommend a closed reduction. Minimally invasive techniques like ORIF of condylar fractures under endoscopic visualization may gain acceptance, anatomical reduction, occlusal stability, rapid function, maintenance of vertical support, avoidance of facial asymmetry, less postoperative TMJ disorder incidence and no maxillomandibular fixation.18,19

In this case report, in addition to surgical treatment, a conservative treatment was instituted for the condylar fractures. The closed treatment of ramus, body, and symphysis fractures may require extended periods of MMF from 3 to 5 weeks. This can become an aggravating factor when it comes to the treatment of pediatric patients, since the level of cooperation is greatly reduced.

For the bilateral condylar fracture, a conservative treatment was instituted, followed by guidelines for initiation of therapy as early as possible. According to Norholt et al. 1993, isolated condyle fractures have been successfully treated with closed functional therapy. Several studies have recommended the use of prefabricated acrylic splints as a treatment for pediatric mandibular fractures. Theses splints are more reliable than open reduction or MMF techniques with regard to cost effectiveness, ease of application and removal, reduced operation time, maximum stability during the healing period, minimal trauma for adjacent anatomic structures and comfort for young patients.20

The treatment of pediatric fractures is perhaps one of the themes explored by the oral and maxillofacial surgery and one of the most contradictory. We believe that regardless of the methodology, minimized injuries should always be the choice. In our case, we chose a conservative treatment in condylar fractures and in the symphysis region, a surgical treatment by anatomic reduction and minimally invasive rigid internal fixation, restoring occlusion with a maximum of fixation while preserving the tooth germs by means of smaller functional monocortical screws.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.