An increasing number of transgender minors are seeking help during the development of their gender identity and transitioning. Understanding their characteristics and the impact of transitioning on their mental health would be of help in the development of protocols to offer a better assistance to this population. The aim of this study was to examine the socio-demographic characteristics and clinical data related to gender identity, transitioning and persistence of transgender minors who were seen at the Gender Identity Unit (GID) of Catalonia, Spain.

Material and methodsAll underage applicants who requested clinical assistance at the specialized GID from 1999 until 2016 were retrospectively evaluated using the minors’ medical records.

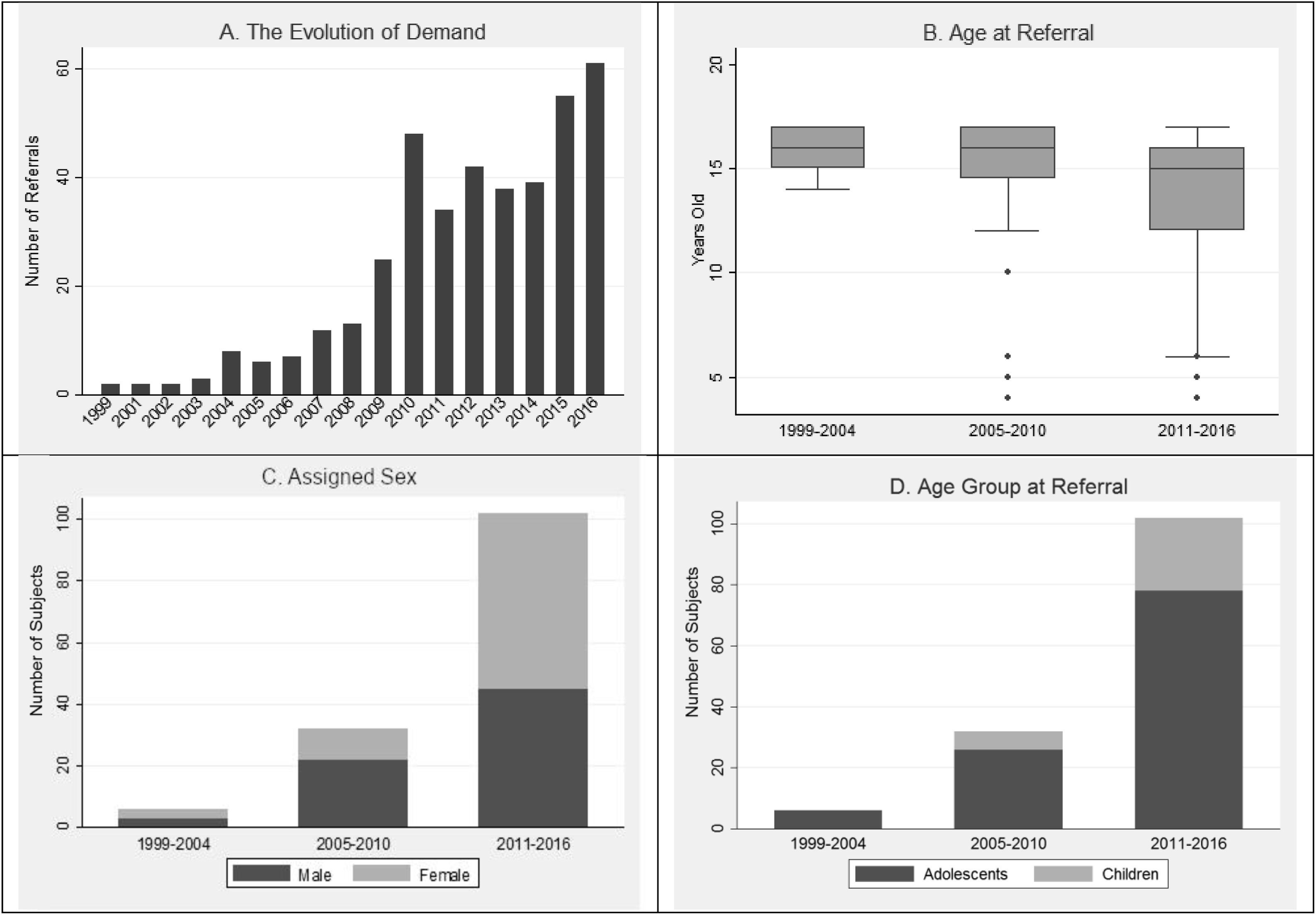

Results124 out of 140 minors were confirmed as being transgender, 83.1% of them were adolescents. The assigned male/female ratio was 1:1.2. 97.6% persisted in their transgender identity after a median follow-up time of 2.6 years. Prior to the first meeting, 48.5% were living in their affirmed role and, by the end of the study, this percentage rose to 87.1%. Yearly, the number of referrals exponentially grew whereas the age at referral decreased (rs=−0.2689, p=0.0013). Child consultations rose to a significant percentage (23.5%) over the last 6 years.

ConclusionsOver the 18-year period, the number of referrals increased considerably, more assigned natal female minors and children were seen, and more minors made the decision to go through social transition at a younger age. In contrast with other epidemiological studies conducted in this field, a consistently high rate of persistence was observed.

The American Psychological Association defines gender identity (GI) as “a person's deeply felt, inherent sense of being a boy, a man, or male; a girl, a woman, or female; or an alternative gender that may or may not correspond to a person's sex assigned at birth or to a person's primary or secondary sex characteristics”.1 Its development is established at an early age.2,3 The term “transgender” is “an umbrella term used to describe the full range of people whose GI is not fully aligned with their sex assigned at birth”.1 Readers are referred to Supplementary Table A for a list of terms and definitions that include various gender identity labels and related concepts.1,41

The role of the medical community regarding GI is to provide psychological guidance for children, adolescents, adults and their families, who experience difficulties in the development of their GI and to provide trans-specific healthcare for transgender people who decide to undergo the transitioning process.

With the intention of depathologizing gender non-conforming expressions and identities, the medical term “Gender Identity Disorder” has been removed from medical classifications and two new concepts have been defined in order to unify criteria in the medical field and to be able to keep providing trans-specific healthcare.5 In 2013, the DSM-5 adopted the term gender dysphoria to refer to clinically significant psychosocial stress associated with gender non-conformity, rather than the condition itself.6 For the 11th version of the ICD, the WHO recommended to rename transgender identity as gender incongruence and is defined as “a marked and persistent incongruence between an individual's experienced gender and the assign sex”.7

Deciding the best moment for minors (children and adolescents) to socially transition is a controversial issue within the medical community.8–10 More and more, minors are taking this step at a younger age. Until now, though, it has been difficult to support this decision before puberty, given that the main epidemiological studies on transgender identity persistence suggested a low rate of persistence in children into adolescence and young adulthood (12%-50%).11–13 However, these results are now being questioned1 and recent Spanish publications have reported a higher persistence rate in minors.14,15 In addition, recent studies have shown that socially transitioned transgender children have lower rates of internalizing psychopathology compared with those living according to their assigned sex.8,16

In the last two decades, there has been a substantial increase in the clinical referrals of minors to GI health services in North America17–19 and in Europe.20–22 Therefore, there is a growing scientific interest in defining the sociodemographic characteristics of transgender minors and in studying the evolution of these characteristics over time in order to provide better guidance and medical intervention strategies.

In the last 20 years, multidisciplinary Gender Identity Units (GIUs) have been developed progressively in several Spanish communities, and in the last few years, new models of attention have been established.15,23 However, at the time the study was performed,24 the GIU of Catalonia, established in the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, was the only GIU available in the public health system of the community of Catalonia, a region with approximately 1.4 minors at that time.25 This unit also offers guidance to minors and their families during the process of gender identity development and social and hormone transition when needed. By the end of 2016, 11% of attended cases in our unit were minors.

This study seeks to extend the knowledge related to demographic characteristics and the clinical data related to transgender children and adolescents, their transitioning process, the persistence of transgender identity across time and its evolution by analyzing 18 years of minor-related data collected from the GIU of Catalonia.

Materials and methodsParticipantsThe study comprises a retrospective observational clinical records review of all minors (under the age of 18) who attended the Catalonian GIU between January 1999 and December 2016, and no exclusion criteria were applied. Altogether a total of 140 minors were included. The referrals were made by pediatricians, general practitioners, mental health specialists or endocrinologists from Catalonia.

ProcedureA cross-sectional retrospective study using child and adolescent’ medical records was carried out. This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clinic de Barcelona (HCB/2016/0824). Informed consent was not requested because of the retrospective nature of the study. Data collection took place in the form of a retrospective review of clinical records and a Microsoft database was created for the data extraction measures, only accessible by approved researchers. Personal data was protected by performing basic data pseudonymization.

The assessments took place in an outpatient setting and comprise of semi-structured and free format assessments and interviews with a child psychiatrist and a child psychologist. The minor and their parents/guardians were seen together and separately. Through the first interviews, specific aspects related to a transgender identity were assessed, such as if the minor expressed cognitions of belonging -or desire to belong- to a gender different to the one assigned at birth, if there were gender non-conforming behaviors, and if some social transition behaviors were present. In the follow-up, semi-structured interviews systematically included questions about the persistence of transgender identity, the evolution of the social transition, and hormonal treatment. The evolution of the social transition was assessed according to changes in appearance and name, the preferred gender pronoun, and the sharing of their affirmed gender with others.

The interest, initiation or evolution, and the type of hormonal treatment, where appropriate, were systematically assessed. All the below described measures were collected using all the material available after the assessment.

VariablesThe data described here were derived from each subject's initial and consecutive appointments at the GIU. The variables collected for the study were: (1) sociodemographic data including age, assigned sex, education level and family structure; (2) date of the first and last visit at the GIU; (3) affirmed gender (female or male); (4) transgender identity (yes/no/under evaluation) and the persistence or not of transgender identity at the end of the follow-up (yes=persister or not=desister); (5) complete social transition (yes/no) and at what age; and (6) hormonal treatment (yes/no), age at treatment initiation and type (puberty suppression with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone [GnRH] agonist or cross-sex hormones).

For this study, affirmed gender was defined as a binary variable. We use the term “transgender” to refer to minors who had a binary identity (male or female) and for whom this identity was not aligned with their assigned sex. This means assigned male minors who self-identify as females and assigned female minors who self-identify as males, regardless of whether they fulfil the diagnostic criteria for gender dysphoria in the DSM-5.16 Transgender identity was categorized as “yes”, “no”, or “under evaluation“. Reasons for being “under evaluation” included: (a) being within the gender assessment process; (b) psychiatric disorders which were affecting the gender identity development process; or (c) the experiencing of doubts about gender identity without a strong transgender identification.

A complete social transition was recorded when the transgender minor adopted the gender expression of their affirmed gender in their private, public and academic/professional lives.

A subject was considered a persister if the last clinical record showed that the minor (1) reported not identifying with the assigned sex, (2) maintained the social transition (where appropriate), and (3) maintained hormonal treatment (where appropriate). Otherwise, a subject was considered a desister if they had initially been categorized as transgender and at the end of the study: (1) the subject's gender identity did not differ from the assigned sex, (2) the subject experienced serious doubts about their gender identity leading to reverse the social transition, or (3) discontinuation of hormonal treatment. Abandoning the follow-up at the GIU was not a criterion for being considered a desister. Subjects who abandoned the follow-up were also recorded and included in the statistical analysis by taking into account the specific follow-up time of each subject.

Finally, the variable”year of referral” data were aggregated into three intervals of 6 years each for the frequency distribution analysis (1999–2004, 2005–2010 and 2011–2016).

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was conducted using Stata for Windows (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13). For the descriptive statistics, means and standard deviations were calculated for normally distributed continuous variables while medians and interquartile range (IQR) were used for the not normally distributed ones. Frequencies and percentages were generated for nominal and categorical variables.

Univariate differences in clinical data were calculated with the Mann–Whitney non-parametric test. Comparisons of proportions between groups were conducted applying the chi-squared test.

Furthermore, Spearman correlation models were used to analyze potential lineal correlations of the changes in clinical characteristics across time.

ResultsSociodemographic characteristics of the sampleOut of 140 minors initially included, 124 were confirmed transgender minors, 7 were under evaluation at the end of the study (6 of whom were children), 7 were not transgender, and 2 abandoned the follow-up before the assessment was completed.

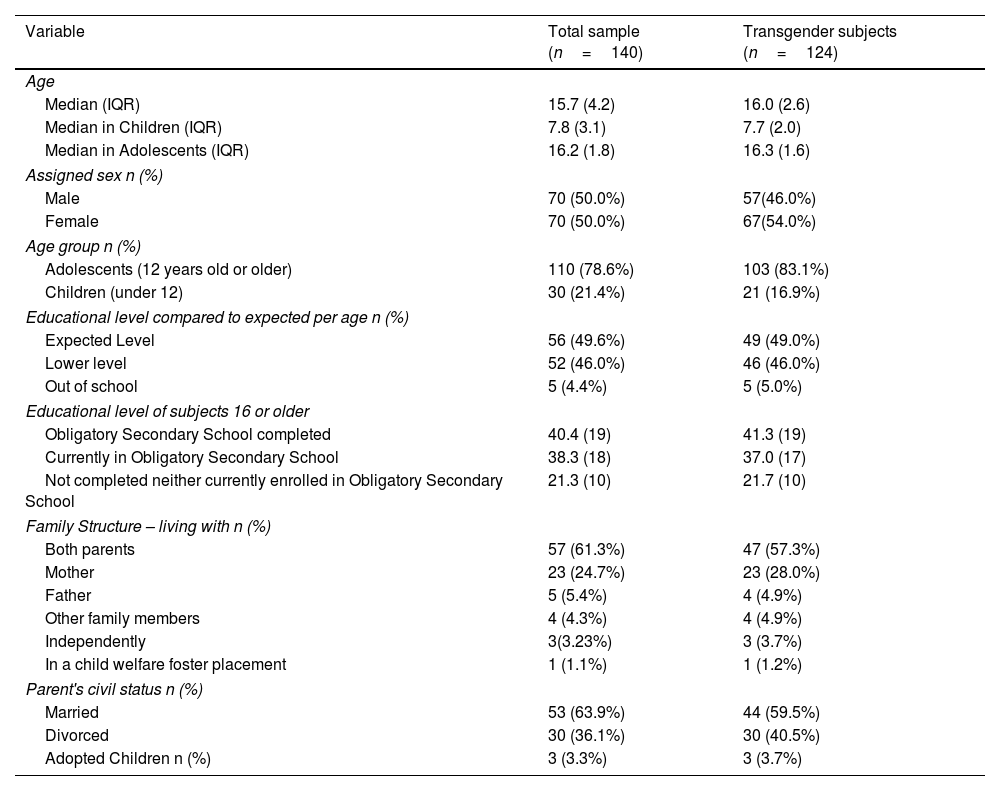

As shown in Table 1, out of 124 transgender minors, 103 (83.1%) were adolescents (aged 12–17.9) and 21 were children (under the age of 12). The assigned male/assigned female sex ratio was 1:1.2, without significant differences between age groups. However, taking the whole sample of 140 minors, the specific assigned sex ratio was 2:1 in children and 1:1.2 in the adolescent group.

Sociodemographic characteristics of referrals according to all subjects and transgender minors.

| Variable | Total sample (n=140) | Transgender subjects (n=124) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Median (IQR) | 15.7 (4.2) | 16.0 (2.6) |

| Median in Children (IQR) | 7.8 (3.1) | 7.7 (2.0) |

| Median in Adolescents (IQR) | 16.2 (1.8) | 16.3 (1.6) |

| Assigned sex n (%) | ||

| Male | 70 (50.0%) | 57(46.0%) |

| Female | 70 (50.0%) | 67(54.0%) |

| Age group n (%) | ||

| Adolescents (12 years old or older) | 110 (78.6%) | 103 (83.1%) |

| Children (under 12) | 30 (21.4%) | 21 (16.9%) |

| Educational level compared to expected per age n (%) | ||

| Expected Level | 56 (49.6%) | 49 (49.0%) |

| Lower level | 52 (46.0%) | 46 (46.0%) |

| Out of school | 5 (4.4%) | 5 (5.0%) |

| Educational level of subjects 16 or older | ||

| Obligatory Secondary School completed | 40.4 (19) | 41.3 (19) |

| Currently in Obligatory Secondary School | 38.3 (18) | 37.0 (17) |

| Not completed neither currently enrolled in Obligatory Secondary School | 21.3 (10) | 21.7 (10) |

| Family Structure – living with n (%) | ||

| Both parents | 57 (61.3%) | 47 (57.3%) |

| Mother | 23 (24.7%) | 23 (28.0%) |

| Father | 5 (5.4%) | 4 (4.9%) |

| Other family members | 4 (4.3%) | 4 (4.9%) |

| Independently | 3(3.23%) | 3 (3.7%) |

| In a child welfare foster placement | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| Parent's civil status n (%) | ||

| Married | 53 (63.9%) | 44 (59.5%) |

| Divorced | 30 (36.1%) | 30 (40.5%) |

| Adopted Children n (%) | 3 (3.3%) | 3 (3.7%) |

IQR=interquartile range.

By the end of the study, 97.6% of transgender minors persisted in their identity, with a median follow-up time of 2.6 years (IQR 4.7). 56.4% of transgender minors had been followed for at least 2 years and 29.8% for at least 5 years. In the sample composed of transgender children all of them persisted in their affirmed gender, with a follow-up period of at least 2 years in 38.1% (n=8) of the sample and of at least 5 years in 23.8% (n=5) of the sample. Three of the transgender children became adolescents and one reached adulthood during the follow-up period.

DesistersThere were three desisters, all of whom were assigned male at birth. Two expressed their doubts regarding being transgender during adolescence: one of them during the second year of the follow-up and after initiating hormonal treatment; and the other during the third year of the follow-up, without having initiated hormonal treatment. Neither had socially transitioned. Confusion regarding both their GI and their sexual orientation was observed in these adolescents. The third one experienced doubts during adulthood, after more than five years of follow-up and a completed transition (socially, hormonally and surgically). At the end of the follow-up, the subject was ambivalent about their GI, which resulted in low adherence to hormonal treatment.

Social transitionPrior to the first meeting, 48.5% had already completed their social transition. During the first year of the follow-up, this percentage increased to 75.2%, and, by the end of the study, to 87.1%. One adolescent reversed their social transition due to desisting in their transgender identity. 24% went through their social transition before puberty.

The median age for social transition was 15.7 years old (IQR: 4.5; range: 4.3–27.8). It mainly occurred around the ages of 8 and 16 in children and adolescents, respectively.

The proportion of affirmed females who had socially transitioned at the end of the study is statistically higher compared to the proportion of affirmed males who had socially transitioned (Pearson χ2=8.3481, p=0.004). However, there is no significant difference in the age of transitioning between genders (z=1.179, p=0.2383, Two-sample Mann–Whitney test), nor in the age at first referral (z=−1.368, p=0.1712, two-sample Mann–Whitney test).

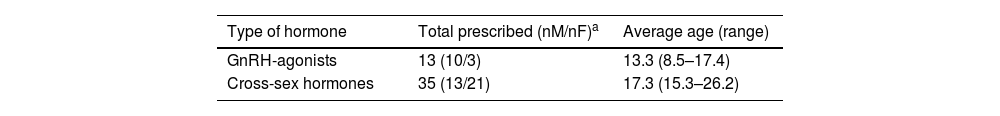

Hormonal treatmentThe type of hormonal treatment (puberty suppression with GnRH analogues and cross-sex hormones) is summarized in Table 2.

Hormonal treatment regarding gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH-agonists) and cross-sex hormones.

| Type of hormone | Total prescribed (nM/nF)a | Average age (range) |

|---|---|---|

| GnRH-agonists | 13 (10/3) | 13.3 (8.5–17.4) |

| Cross-sex hormones | 35 (13/21) | 17.3 (15.3–26.2) |

The number of referrals yearly exponentially grew (Fig. 1A) and the age at referral decreased (Fig. 1B). An increase in assigned female minors, particularly during the last period, was observed (Fig. 1C). There were no referrals of assigned female children until the last period (2011–2016), when ten were seen, which represents 41.7% of child referrals in the last period. Another remarkable change is that, in the last years, children represent a significant proportion of the sample (Fig. 1D).

Evolution of the sample over the 18-year period. A. Number of referrals (N=140). B. Age at referral according to the three periods of time (N=140). C. Comparison of assigned sex across time (N=140). D. Proportion of children and adolescents at referral according to the three periods of time (N=140).

The percentage of minors who socially transitioned prior to contact with the unit remained around 50% over time. However, none of the children had socially transitioned before contacting the unit until the third period, when a total of seven children were already living in their affirmed gender expression at the time of their first visit. Over the years, minors referred to our clinic were more willing to socially transition at younger ages (rs=−0.2689, p=0.0013).

Regarding hormonal treatment, the percentage of subjects who underwent cross-sex hormone therapy from 2005 to 2016 remains consistent. In contrast, puberty suppression was mainly prescribed during the last six years. However, the average age for initiating GnRH treatment did not significantly differ between the final two periods, being around 13.5 years in both. In our sample only one child began the treatment before the age of twelve.

DiscussionThis retrospective study is the first to provide demographic and clinical data on transgender minors assessed at a GIU in Catalonia. Some relevant demographic changes have been observed from 1999 to 2016. A significant increase in the proportion of natal girls and a decrease in the age of referral and the social transition has been reported over the years. In addition, this study provides data about transgender persistence in minors that contrasts with other epidemiological studies conducted in this field.12 After a median follow-up time of 2.6 years, a consistently high rate (97.6%) of persistence of transgender identity in minors was observed.

Extending previous studies,20,26 this study found an increase in the number of minors seeking attention in our GIU and at younger ages. A possible explanation for this change could be that pediatricians and mental health professionals have received more medical training and are more aware of the importance of access to specialized care in improving patients’ well-being that, regardless of the clinical approach, is often complex and requires interventions involving families and social environments.27 In addition, the fact that the main increase in referrals coincided with the creation of the specifically for minors GIU in our hospital (in 2008) may suggest, as has been observed in other countries,28 that providing specialized units with trained professionals for this process may help to ensure access to these services.

Regarding sex differences, as the studies of Cohen-Kettennis et al. (2003)29 and Di Ceglie et al. (2002)30 have shown, assigned male minors and their families sought help at younger ages, to the extent that in our unit, the number of assigned male children is twice the number of assigned female children. However, the sex ratio of the whole sample approaches 1-to-1 due to the larger number of assigned female adolescents. The 2-to-1 ratio has also been observed by other authors,15,31 although 1-to-1 sex ratio prevalence in adolescents has also been reported.28

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the number of assigned female minors attending our clinic, in both adolescent and child age groups. This overrepresentation of natal girls has also been reported by few other GIU, mainly in the adolescent group.31,32 Although the reason for this demographic change is unknown, it has been hypothesized that, since cross-gender behaviours in assigned female individuals are more socially accepted than in assigned male individuals, transgender men experienced less gender dysphoria through social transition than transgender women.33 Therefore, we assume that it is not until barriers to care are lowered that transgender male seeks a more complete resolution of their dysphoria.

The percentage of transgender minors in our sample who persisted in their transgender identity was notably high. These findings are in line with the results reported by other GIUs of Spain,14,15 where 97%; n=136 and 95%; n=45 transgender minors persisted in their transgender identity. Nonetheless, our persistence rates starkly contrast with the main literature, in which a minority of children (12–50% across studies) will continue to persist in their affirmed gender into adolescence and adulthood.11,12,34 Different reasons may explain this considerable difference between our results and the previous literature. We argue that, unlike our study, previous studies on gender identity in minors considered as “transgender minors” not only those whose affirmed gender was different from the assigned sex, but also those minors who merely presented socially unaccepted gender behaviours in accordance with their assigned sex. Furthermore, in those studies, about 30–62% of minors who abandoned the follow-up were classified as desisters, even if their GI was unknown.12,35 In this study, abandonment of the follow-up was not a criterion for being considered a desister because it was not known whether the reasons for abandonment were related to desistence or other causes.

There is a remarkable increase in the number of children who are willing to socially transition and of those who have gone through this process prior to their first contact with our GIU.16,36 It should be taken into account that “coming out” is related to social and cultural context.37,38 Therefore, greater visibility and more permissive social attitudes with respect to gender diversity may have facilitated the expression of non-conforming GI in society.39,40

Regarding hormonal treatment, a decrease in the referral age in the final period is allowing more minors to undergo puberty suppression, which could positively impact physical outcomes. Developing a greater awareness and understanding of one's gender identity can be a difficult and confusing process, particularly during the adolescent development period. Thus, puberty suppression may give the adolescent time to explore their gender identity without developing irreversible secondary sex characteristics. However, in our view, in cases where the GI is well established such delays are not necessary before further medical decisions are taken. In addition, even though affective disorders can influence self-identity, in the presence of gender dysphoria steps towards transitioning could lead to mood stability and be of help in clarifying their GI.16

Study findings should be interpreted alongside several limitations. First, the retrospective nature of the study is subject to common limitations of this research design. This is a cross-sectional study and therefore no conclusions can be drawn about changes over time. Second, the median follow-up time of 2.6 years may be considered a relatively short follow-up period to assess long-term persistence. Third, we defined the GI as a binary variable and other possible identities were not taken into consideration. However, in Olson's 2016 study, only ten out of 151 adolescents defined their gender outside the binary system, and all transgender children had binary identities.16 Finally, youth in this study were seeking care at an urban community-based mental health service; thus, only contains data from a single unit and findings may not generalize to other clinic settings and geographic locations.

On the other hand, the strengths of this study should also be considered. To our knowledge, the majority of previous studies only recruited adolescents, and here we present one of the largest samples of transgender minors which also includes a child group. This is one of the few studies concerning transgender identity in minors where the specific follow-up period of each individual has been registered. In our opinion, it is essential that this variable is recorded in order to determine the reliability of the persistence data.

Although prospective and long-term studies are needed to further examine the factors associated with the persistence and need for psychological support of transgender minors, this observational and naturalistic approach has the advantage of reflecting the daily clinical practice.

ConclusionsIn summary, our results highlight a significant increase in the incidence of minors seen in the GIU, an increase of the proportion of natal girls and a decrease in age at referral. In addition, transgender minors are more willing to go through social transition at younger ages. Qualitative research taking transgender population's perspective is necessary to better understand these demographics changes. To our knowledge, this is the study which reports the highest persistence of transgender identity in minors.

Ethical approvalEthical approval was granted by the local Ethics Committee (2016/0824).

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestsDr. Solerdelcoll receives grant support from the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All persons who made significant contributions to this study and the manuscript are included in the author list.

The authors would like to thank Anthony Burr, M.Ed. who provided writing assistance and language editing. We would also like to offer special thanks to the staff of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. Poster has been presented at the 23rd World Congress of the International Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions (IACAPAP) on July 23–27, 2018, Prague, Czech Republic.

Present address: Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King's College London, London, UK.

Present address: Department of Medicine, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.