Perinatal Mental Disorders are considered a public health problem due to the impact on both, the maternal health and the children, in the short and long term. During 2018, at the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona, the first Mother Baby Day Hospital (MBDH) in Spain was developed and implemented.

MethodThe first 150 dyads (mother and baby) attended from January 2018 to October 2021 were selected. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were described. The clinical variables studied were anxious and depressive symptoms, mother–baby relationship and maternal functionality.

ResultsThe mean age of mothers was 34 years and of babies 3.7 months. 80% had a psychiatric background and 30.7% had required some psychiatric inpatient admission. 48.7% of the patients were diagnosed with a major depressive episode and a half had some psychiatric comorbidity (54.7%). One in 3 patients admitted had a moderate–high suicidal risk and 10.7% had attempted suicide in the current episode. At discharge, significant improvements were observed in the scales of depression (EPDS), anxiety (STAI-E), mother–baby relationship (PBQ) and functionality (HoNOS).

ConclusionsThe MBDH allows us a comprehensive, intensive and multidisciplinary care for postpartum mothers with a mental disorder with good results and containment of risk behaviours. Likewise, MBDH allows us to detect and to intervene in bonding difficulties and maternal care giving.

Perinatal Mental Disorders (PMD) are considered a public health problem due to the impact on both the maternal health and quality of life their children in the short and long term. 20% of women will suffer a mental disorder throughout pregnancy and/or postpartum period.1,2 It is estimated that the cost of untreated PMD is more than 9 billion of euros per year, and 72% of this cost is attributable to the consequences on the child.3 Women with postpartum depression or severe mental illness in perinatal period may experience more stress, less responsiveness and contact with their babies and the negative perception of baby's difficult temperament with responses of anxiety or hostility.4 Some studies highlight that treatment focused solely on maternal psychopathology may be insufficient to address the negative impact of maternal mental disorder on the child development and attachment.5,6 However, outpatient mental health facilities generally do not be able to allow women to attend with their babies, nor do they address the mother–baby interaction, not even maternal care abilities. Also, for women with severe mental illness who require hospitalization it involves mother–baby separation, discontinuation of maternal care and, in many cases, the end of breastfeeding.

The International Clinical Guidelines for Perinatal Mental Health7–9 highlight the need to improve the detection, prevention, and treatment of PMD with the development of devices that integrate dyad care by specialists in perinatal mental health. United Kingdom, France, Holland, Belgium, Germany, India, Australia and USA have inpatient mother–baby psychiatric units (MBU) as well as specialized community services.

The MBUs are inpatient units conformed by multidisciplinary teams focused on treating mothers’ mental health, generating positive interactions between mothers and babies, and helping them to acquire childcare skills. Gillham y Wittkoski10 conducted a systematic review of 23 studies about psychological outcomes following MBU admission indicating positive effects on maternal mental health and the mother–infant relationship and an absence of adverse effects on child development. Moreover, patients prefer admission with their baby and MBUs ensure more family- and perinatal period-focused care, and are better equipped to fulfil women's needs.11

Until now, we have not many data on another less developed model of care, the partial hospitalization. In the United States, MBDH programs have been created and are conformed by a multidisciplinary team. The intervention model includes: emotional regulation groups, interventions targeted to the mother–baby relationship, psychoeducation activities and sessions about social skills, baby care or yoga.12–14 All of them have shown good results at discharge in the self-reported scales of depression, anxiety and maternal functioning and good acceptance by the patients. The main difference between them is the length of admission, which ranges from 20h of group therapy per week during 4 weeks13 to 2 days per week with an average of 14 weeks.14

In line with the recommendations described, in 2018, the first Mother–Baby Day Hospital (MBDH) in Spain was developed and implemented at the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona. The present study describes the characteristics of this device and resumes the most relevant data of the first 150 dyads attended.

The MBDH offers an intensive and multidisciplinary care and treatment model for PMD from birth to first postpartum year. The MBDH permit early intervention, continuity of care focused on the mother–baby dyad and favours the recovery processes of the mental health and maternal functioning. The team is composed by psychiatry, clinical psychology, nursing (specialized in mental health and paediatrics) and social work. It includes intensive intervention from Monday to Friday from 9:30a.m. to 4:00p.m. and psychopharmacological treatment, psychological therapies and nursing and social interventions are applied. Mothers are admitted with their babies and take care of them with different levels of nursing supervision, and we offered a stay of up to 60 sessions (one session=1 day). Any health professional from Catalonia could refer a woman with a mental disorder and/or a bonding disorder in the first postpartum year. Women with a history of serious perinatal mental illness and/or mental illness with a high risk of postpartum decompensation such as bipolar disorder can also benefit from MBDH. The exclusion criteria are the substance use as a primary diagnosis, the high risk of aggressive behaviours that requires psychiatric hospitalization and mothers who do not have legal custody of their babies (mainly due to the intervention of Social Services for Child Care). Referrals are assessed within 2 weeks by perinatal psychiatry. Until now, the flexibility of the dyad's attendance schedules has made it possible to serve up to 23 dyads in the same period, avoiding waiting list.

Material and methodsA total of 150 dyads attended from January 2018 to October 2021 have been included. The inclusion criteria were: (1) have a mental disorder according to DSM-5 criteria15 and/or a bonding disorder with the baby in the first postpartum year; (2) voluntary acceptance to receive treatment at MBDH; and (3) ability to answer self-administered questionnaires. The study has the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Hospital (HCB/2021/1233).

Evaluation instruments- -

MINI (Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview)16,17: Brief structured diagnostic interview that explores the main psychiatric disorders of Axis I of DSM-IV and ICD-10. Use for the evaluation of suicidal risk that is established in 4 categories according to the score obtained: (1) no risk, (2) mild, (3) moderate, (4) severe.

- -

EPDS (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale)18,19: Self-administered scale for the evaluation of depressive symptomatology in the postpartum period. It is a scale with 10 items that score from 0 to 4 and with a total score between 0 and 30. This scale is used internationally as a measurement and screening for perinatal depression. The cut-off point in the Spanish population is 11.

- -

STAI (State Trait Anxiety Inventory)20: Self-administered scale to assess anxious symptoms. It consists of two factors (state and trait); in this study, we used the first factor (state anxiety, STAI-E). The state anxiety scale consists of 20 items with 4 possible Likert-type responses (0–3).

- -

PBQ (Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire)21,22: Self-administered scale to assess the mother–baby relationship difficulties. It is a scale with 25 questions that score from 0 to 5. The cut-off point for possible bonding disorder is 13 and 18 for severe bonding disorder.

- -

HoNOS23,24: Hetero-administered instrument conformed by 4 scales designed to measure the various physical, personal and social problems associated with mental illness. The total score, between 0 and 48, represents the global severity; a higher score indicates greater severity.

- -

Bayley III25: Cognitive, language, and motor development assessment scale for children between 1 and 42 months of age.

At the first visit, sociodemographic data (maternal and baby age, country of birth, educational level, relationship with the partner, economic situation), obstetric and neonatal variables (sex of the baby, pregnancy planning, type of feeding), personal psychiatric history (previous psychiatric history, psychiatric admissions) and family history are collected. In this visit, the psychiatric diagnosis is made according to DSM-515 (main diagnosis and comorbidities) and suicidal risk is assessed (by clinical interview and by the MINI suicide risk scale). All patients completed auto-administered questionnaires (EPDS, STAI-E and PBQ) and at the first visit with mental health nurse HoNOs interview is administered. Neurodevelopment and health aspects are evaluated for all babies at admission. Paediatric nurse assess the level of maternal autonomy for the basic care of the baby through a scale developed by professionals from the MBDH. This scale, based on the observation of maternal behaviours, includes 9 domains: hygiene of the baby, bathing the baby, diaper changing, dressing the baby, feeding the baby, detection risk signs, interact with the baby (massage, sing, play), going for a walk with the baby, getting the baby to sleep. EPDS, STAI, PBQ and HoNOs at administered at discharge. Finally, all women are assessed by social worker, ensuring a holistic vision with community and family interventions if necessary.

Considering the specific characteristics of this service, treatments and interventions for PMD have been developed and/or adapted, considering the inclusion of the baby and aspects related to maternal care. Activities are mostly done in groups to facilitate modelling and improve stigma. Everyday a psychological intervention group is conducted (Unified Barlow Protocol Transdiagnostic Treatment26; Postpartum Depression Group Treatment based on Milgrom Protocol27; Mother–baby bonding Group). Subsequently, activities are carried out by the mental health nurse (psychoeducation groups, healthy habits, physical exercise, dance) and by the paediatric nurse (workshops about health care of infants, complementary feeding, and baby massage).

Perinatal psychiatrist carried out the risk-benefit assessment of psychopharmacological treatment, as well as clinical monitoring (clinical response and adverse effects) and blood levels analysis of those drugs that require it during lactation.

More specifically, specialized individual psychological interventions have been developed for perinatal Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and/or intrusive thoughts of infant-related harm through intensive Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) and for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) through Eyes Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR). Likewise, in some cases with severe bonding disorder, intervention with video feedback is performed.

Statistical analysisA quantitative descriptive study has been conducted with the aim of defining the sociodemographic characteristics, psychiatric history and clinical variables of the women attended. The categorical variables have been described as N (%) and the continuous variables as means with their standard deviation (SD). Paired sample t-tests were used to compare the questionnaires results at admission and discharge (EPDS, STAI, PBQ y HoNOs) considering significant a value of p less than 0.05. A linear regression analysis was performed to analyse the variables associated with the number of sessions in MBDH, introducing those variables that showed significant mean differences for the total number of sessions. All data were analysed using SPSS, version 23.

ResultsThe total sample was composed of 150 dyads (150 mothers and 151 babies). Half (52.7%) were referred from outpatient Mental Health Service, 11.3% from the emergency department or inpatient psychiatric unit, 14.7% from Obstetrics/Midwives, 11.4% from Primary Care and the rest from other devices or at the request of the patient/family. Of the 150 patients admitted to the MBDH, eight (5.3%) required admission to the inpatient Psychiatric Unit and 16 (10.7%) requested voluntary discharge from MBDH.

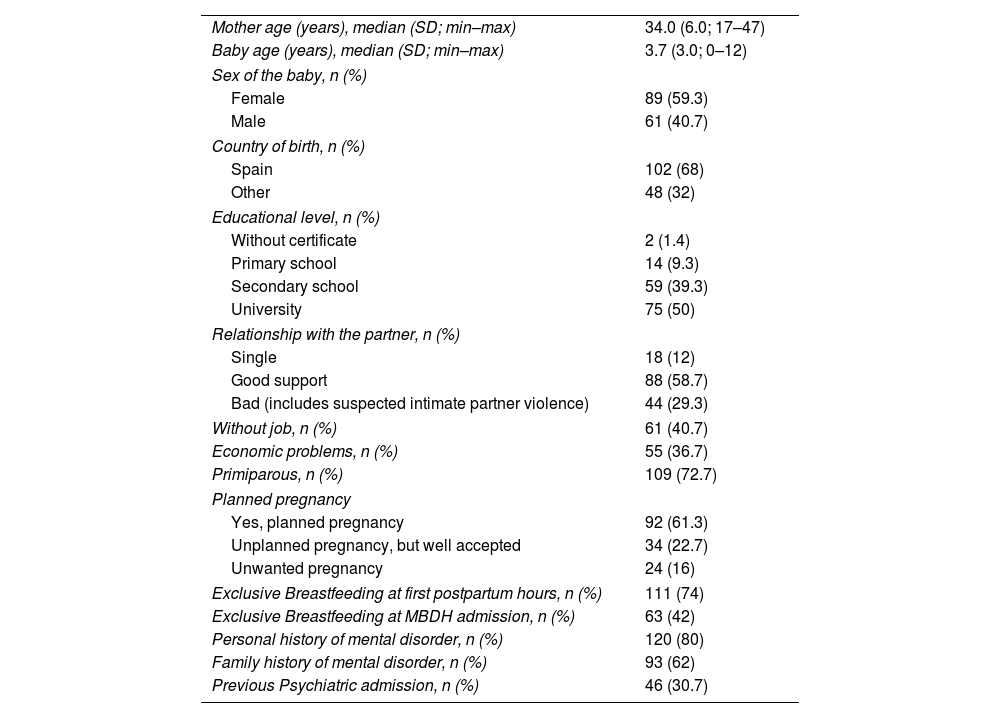

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are summarized at Table 1. Most of patients were born in Spain (68%), had a partner (88%) and had completed higher education (50%). 40.7% did not have a job and 36.7% reported economic problems. A third of the sample had unplanned pregnancy and 72.7% were primiparous. Most of women started exclusive breastfeeding after delivery and 40.7% maintained it upon admission to MBDH. 80% had a personal psychiatric history and 30.7% had had a previous psychiatric admission.

Sociodemographic, obstetrical and clinical characteristics.

| Mother age (years), median (SD; min–max) | 34.0 (6.0; 17–47) |

| Baby age (years), median (SD; min–max) | 3.7 (3.0; 0–12) |

| Sex of the baby, n (%) | |

| Female | 89 (59.3) |

| Male | 61 (40.7) |

| Country of birth, n (%) | |

| Spain | 102 (68) |

| Other | 48 (32) |

| Educational level, n (%) | |

| Without certificate | 2 (1.4) |

| Primary school | 14 (9.3) |

| Secondary school | 59 (39.3) |

| University | 75 (50) |

| Relationship with the partner, n (%) | |

| Single | 18 (12) |

| Good support | 88 (58.7) |

| Bad (includes suspected intimate partner violence) | 44 (29.3) |

| Without job, n (%) | 61 (40.7) |

| Economic problems, n (%) | 55 (36.7) |

| Primiparous, n (%) | 109 (72.7) |

| Planned pregnancy | |

| Yes, planned pregnancy | 92 (61.3) |

| Unplanned pregnancy, but well accepted | 34 (22.7) |

| Unwanted pregnancy | 24 (16) |

| Exclusive Breastfeeding at first postpartum hours, n (%) | 111 (74) |

| Exclusive Breastfeeding at MBDH admission, n (%) | 63 (42) |

| Personal history of mental disorder, n (%) | 120 (80) |

| Family history of mental disorder, n (%) | 93 (62) |

| Previous Psychiatric admission, n (%) | 46 (30.7) |

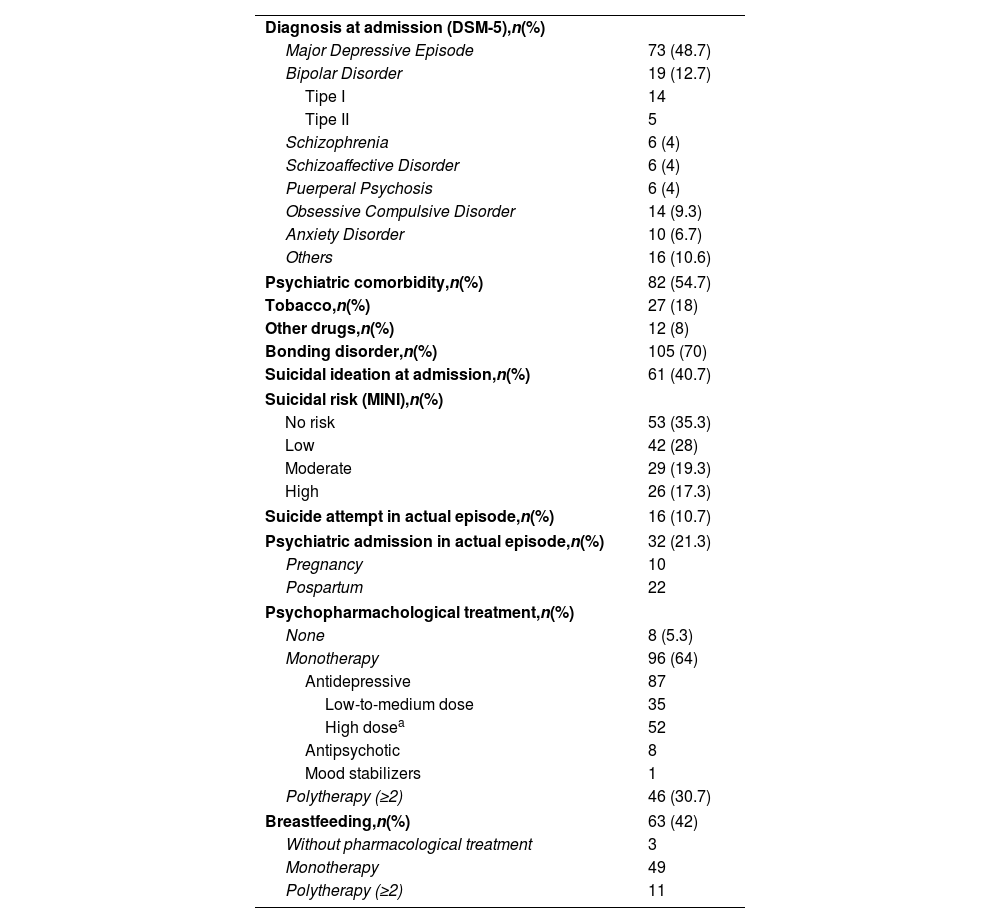

Table 2 shows the main sample clinical characteristics. Almost half of the women had a perinatal onset major depressive episode (48.7%) and 54.7% had at least one comorbidity, mainly anxiety disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder. 70% had a diagnosis of bonding disorder. At admission, 42% reported suicidal ideation in the clinical interview and suicidal risk was detected in 64.7% of women using the MINI scale.

Clinical and treatment characteristics of episode.

| Diagnosis at admission (DSM-5),n(%) | |

| Major Depressive Episode | 73 (48.7) |

| Bipolar Disorder | 19 (12.7) |

| Tipe I | 14 |

| Tipe II | 5 |

| Schizophrenia | 6 (4) |

| Schizoaffective Disorder | 6 (4) |

| Puerperal Psychosis | 6 (4) |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 14 (9.3) |

| Anxiety Disorder | 10 (6.7) |

| Others | 16 (10.6) |

| Psychiatric comorbidity,n(%) | 82 (54.7) |

| Tobacco,n(%) | 27 (18) |

| Other drugs,n(%) | 12 (8) |

| Bonding disorder,n(%) | 105 (70) |

| Suicidal ideation at admission,n(%) | 61 (40.7) |

| Suicidal risk (MINI),n(%) | |

| No risk | 53 (35.3) |

| Low | 42 (28) |

| Moderate | 29 (19.3) |

| High | 26 (17.3) |

| Suicide attempt in actual episode,n(%) | 16 (10.7) |

| Psychiatric admission in actual episode,n(%) | 32 (21.3) |

| Pregnancy | 10 |

| Pospartum | 22 |

| Psychopharmachological treatment,n(%) | |

| None | 8 (5.3) |

| Monotherapy | 96 (64) |

| Antidepressive | 87 |

| Low-to-medium dose | 35 |

| High dosea | 52 |

| Antipsychotic | 8 |

| Mood stabilizers | 1 |

| Polytherapy (≥2) | 46 (30.7) |

| Breastfeeding,n(%) | 63 (42) |

| Without pharmacological treatment | 3 |

| Monotherapy | 49 |

| Polytherapy (≥2) | 11 |

Sixteen patients had attempted suicide during the current episode and 32 had required psychiatric admission in the perinatal period. More than half of the mothers (56.7%) had difficulties with autonomy in caring for the baby in 3 or more of the areas evaluated at admission. Of the babies evaluated, 14% had scores below the 80th percentile on some Bayley-III scale (cognitive, language, or motor).

Almost 100% of the mothers received psychopharmacological treatment (8 patients rejected pharmacological treatment), and 30.7% two or more drugs (excluding anxiolytics). 2/3 of the patients receiving antidepressant monotherapy at high doses (equivalent to ≥40mg/d of paroxetine28). After risk-benefit assessment with psychiatrist all lactating women decided to continue breastfeeding together with the prescribed psychopharmacological treatment.

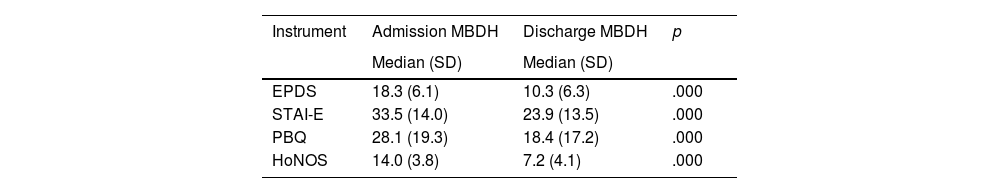

Table 3 shows the scores of the scales at admission and discharge from the MBDH. Significant improvement was observed in all areas evaluated: symptoms of anxiety and depression (STAI-E, EPDS), mother–infant relationship (PBQ), and functionality (HoNOS).

Mean (SD) changes in EPDS, STAI-E, PBQ and HoNOS at admission and discharge of Mother Baby Day Hospital (MBDH).

| Instrument | Admission MBDH | Discharge MBDH | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (SD) | Median (SD) | ||

| EPDS | 18.3 (6.1) | 10.3 (6.3) | .000 |

| STAI-E | 33.5 (14.0) | 23.9 (13.5) | .000 |

| PBQ | 28.1 (19.3) | 18.4 (17.2) | .000 |

| HoNOS | 14.0 (3.8) | 7.2 (4.1) | .000 |

Abbreviations: EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; STAI-S: State Trait Anxiety Inventory-State; PBQ: Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire; HoNOS: Health of the Nation Outcome Scales.

The mean of assistance was 33.7 sessions (SD: 23.16), considering one session the equivalent of one day attending MBDH. A higher number of sessions were significantly associated with a higher EPDS score at admission (beta .338, Sig .001), a history of sexual abuse in adulthood (beta .265, Sig .005) and presence of suicidal ideation in the current episode (beta .231, Sig .021).

DiscussionThis study describes the functioning and characteristics of the dyads attended at the first Mother Baby Day Hospital (MBDH) in Spain and its efficacy in postpartum women with a moderate-severe mental disorder. Mothers treated at the MBDH present a significant clinical improvement in both anxious and depressive symptoms (STAI-E and EPDS), as well as in difficulties on the mother–baby relationship (PBQ) and maternal functionality (HoNOs).

The women admitted to the MBDH have severe mental disorders similar to those of some women admitted to mother–baby units. On the one hand, at admission to MBDH, the patients showed scores on the self-administered scales similar to those of women admitted to mother–baby psychiatric hospitalization units (MBU).29–31 On the other hand, the women admitted have indicators of complexity like: 54.7% of psychiatric comorbidity, 30.7% of previous psychiatric hospitalization, 21.3% of psychiatric hospitalization in current pregnancy/postpartum, 40.7% had suicidal ideation at admission and 10.7% had a suicide attempt in current episode. At discharge, significant improvements have been observed in all evaluations such as those described in the studies of MBU10 or other partial hospitalization devices.12–14

Almost half of the patients were admitted for diagnosis of major depressive episode. Both in the MBU29–32 and partial hospitalization studies,12–14 depression is the main diagnosis of patients, and the presence of comorbidity is common. These findings are expected considering that depression is the most common mental disorder in the perinatal period, with prevalence around 13% in general population studies.1 The median for complete remission of postpartum depressive episode is almost one year,33 and more than half of depressed mothers had bonding.32 Thus, the impact on health and motherhood that occurs with consequences on maternal functioning is reasonable. Therefore, this impact on health and motherhood may require a more intensive intervention for recovery than those that outpatient services could be offered.

Furthermore, 40.7% of the patients had suicidal ideation at admission and 10.7% had attempted suicide in current episode. Suicide is one of the main causes of death in postpartum women. The main diagnoses associated with maternal suicide are severe depression (21%), substance use disorder (31%) and psychosis (38%).34 Studies on postpartum affective disorders describe the presence of suicidal or self-harm ideation in about 17–20% of women.35,36 In our sample the rates of suicidal ideation are higher. Probably because patients with high clinical severity are referred to our unit as it is the only specialized service. It is important to explore suicidal ideation and treat the underlying mental disorder, usually a depressive disorder, not only because of the risk for woman, but also because of the risk to the baby in the short term (injuries, negligence in the care, infanticide) and in the medium-long term.37

Therefore, we considered the need to include babies as at-risk subjects that require early assessments and, in some cases, specific interventions. 14% of the babies evaluated at MBDH had scores below the 80th percentile in some area of neurodevelopment. The relationship between maternal mental disorder and effects on offspring has been explained through different mechanisms, such as genetic factors, the effects of psychopathology on foetal neurodevelopment37 or the impact that maternal mental disorder has on the mother caregiving behaviour or attachment, among others.37,38 Appropriate interventions aimed at promoting positive parenting and establishing secure attachment in the postnatal period are needed, not only to improve maternal capacities but also to reduce risks to infants.

Regarding the number of sessions at MBDH, the patients stay a median of 34 sessions, like those found in the study by Geller et al.14 where they described a median of two days a week for 14 weeks (equivalent to 28 sessions). The possibility of carrying out adaptable sessions according to the needs of each dyad allows us to personalize the intervention and prolong the admission consolidating the clinical improvement and favouring the transition to community devices. Follow-up studies at discharge of the MBU show a high risk of worsening in the first three months on both the relationship with the baby and the maternal psychopathology.39,40 The recovery of women with a perinatal mental disorder cannot be only consider the acute symptomatology but should include the ability to self-care and training for the care of the baby. By achieving this functionality, the transition to the community and to your family and work life will occur more easily.

The principal limitation of this study is that it is an observational study, and we cannot stablish the effect of the interventions separately.

ConclusionsBased on clinical experience and preliminary results, the MBDH model of care allows us an intensive and multidisciplinary intervention for women with a perinatal mental disorder with the possibility to avoid, in some cases, psychiatric hospitalization with mother–baby separation. More specifically, it allows us to observe the relationship of the mother with her baby as well as maternal care behaviours. Also, allow us to direct intervention through observational learning processes (modelling), support for breastfeeding and training in positive parenting. Early intervention in these dyads aims not only to reduce the symptoms but also to improve the autonomy and functionality of the mothers, as well as to carry out prevention for the neurodevelopment of these babies.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.