This review paper analyzes the state of knowledge on Telepsychiatry (TP) after the crisis caused by COVID and the resulting need to use new modalities of care. Six essential aspects of TP are addressed: patient's and mental health staff satisfaction, diagnostic reliability, effectiveness of TP interventions, cost-effectiveness in terms of opportunity cost (or efficiency), legal aspects inherent to confidentiality and privacy in particular and the attitude of professionals toward TP. Satisfaction with TP is acceptable among both patients and professionals, the latter being the most reluctant. Diagnostic reliability has been demonstrated, but requires further studies to confirm this reliability in different diagnoses and healthcare settings. The efficacy of TP treatments is not inferior to face-to-face care, as has been proven in specific psychotherapies. Finally, it should be noted that the attitude of the psychiatrist is the most decisive element that limits or facilitates the implementation of TP.

Although telepsychiatry (TP) may seem to be a novel and current concept, some authors highlighted its potential more than sixty years ago. However, the reality is that we have had to be immersed in the COVID-19 pandemic for psychiatrists to seriously consider the need to learn more about the advantages of TP. The evidence accumulated during this crisis has made it possible to draw up specific guidelines on how to implement this therapeutic approach in pandemic situations.1 Health-care sector experts predict that, regardless of the current pandemic, 50% of healthcare activity will be carried out in digital format by 2030.2

Telemedicine may be defined as the use of communications technology for the provision of quality health care regardless of location, distance or time.3 In our field, TP includes many modalities of communication such as telephone, fax, e-mail, use of the Internet and videoconferencing.4,5

Telepresence or “virtual presence” is an “illusion of non-mediation” where the psychiatrist and patient “…do not perceive or acknowledge the existence of a medium in their communication environment and respond as they would if the medium were not there”.6,7 This concept is fundamental to the success of any TP device based on a videoconferencing system.8 Experts point out that it is a phenomenon whereby technology creates an experience that allows the user to “feel as if they are present, give the appearance of being present, or have an effect in a place other than their actual location”, all of which are critical in the psychiatrist-patient relationship.9

Challenges to care through telepsychiatrySocial distancing, fear of contagion of patients and professionals due to COVID-19 are circumstances that have modified the psychiatrist's relationship with their patients. TP is not going to be a temporary solution, but is going to become a safe, effective, convenient, scalable and sustainable way of providing psychiatric care, and will be as crucial as it is inevitable.10

Based on the criteria proposed by Hubley11 we have considered six conceptual axes in which TP must face different challenges due to its novelty: satisfaction of the user, diagnostic reliability, therapeutic efficacy, cost-effectiveness in terms of opportunity-cost (or efficiency) and the legal aspects inherent to confidentiality and privacy in particular.

The challenge of patient and psychiatrist satisfactionMost studies (based on self-administered quantitative questionnaires) indicate that patients rated their experience with TP services as “good” to “excellent”, especially in rural settings compared to urban settings.12,13

Qualitative studies14,15 highlight as positive aspects the ease of use and lower cost, in terms of money and time, transportation and appointments, and as negative aspects they include concerns about privacy-confidentiality, difficulties in establishing patient–physician relationships and the technical challenge that TP poses for them.

Regarding the satisfaction of the professionals, the results are heterogeneous. On one hand, we found greater satisfaction in the field of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,16 and among Primary Care (PC) physicians, especially those in rural areas, and emergency physicians.17 On the other hand, it has been found that mental health professionals prefer the videoconference modality to the purely telephone consultation and they are concerned that in teleconsultation the patient's level of attention may decrease during the consultation and they may not respond adequately to the questions asked.18

The qualitative studies show that psychiatrists express concerns about the possible drawbacks of TP, especially regarding the therapeutic alliance and the barriers involved in adapting to technology, the lack of access to training in this field, and the lack of adequate and reliable resources.19

The challenge of diagnostic reliabilityWhen comparing the reliability between TP and face-to-face consultation we find that it is very high, as long as it is analyzed using specific standardized instruments or based on structured interviews such as the SCID.20 However, this reliability is lower in cases where visual information from the patient is required, as in psychogeriatrics, or when exploring the adverse effects of psychotropic drugs.21

The challenge of therapeutic efficacyTP has been applied to a wide range of conditions such as major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and bulimia, and we may basically conclude that TP achieves the same or better results than face-to-face consultation. However, we need to remind that these results cannot always be extrapolated to the general population due to the methodological heterogeneity of the studies and the large variability of the therapeutic approaches analyzed.11 Two other elements on efficacy need to be highlighted: patients are more compliant with TP appointments than with face-to-face appointments and TP does not increase the demand for face-to-face consultations either in PC or in Mental Health outpatient facilities after teleconsultations.22

The challenge of efficiencyEvaluating the cost-effectiveness of TP is difficult because the technology is evolving faster than the methods used to measure it, and there are considerable differences between studies, both with respect to their designs, the type of service offered, the population served, the physical distance from the office to home, the technology used, as well as the methods used for analysis. The evidence appears to show that TP-based interventions are similar to or even better than traditional modes of care in terms of cost-effectiveness.11

Current evidence indicates that TP increases access to high-quality mental health care for various populations, which may have lacked such care in the past. It effectively removes several barriers to care, such as distance, transportation difficulties, time constraints, costs, safety, and reduces the stigma associated with going to a psychiatrist's office.23 Consequently, TP reduces the inequalities in care faced by many patients and generates a sense of empowerment among them.

The challenge of legal and ethical aspectsLegal security of telepsychiatryIn the field of telemedicine, both the European Commission and the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that as early as 2009, legal considerations were a major obstacle to its development.24 It is therefore essential to create the legal instruments and the formal ethical guidelines for the proper implementation of TP.23

Regarding the legal responsibility for data protection, the role of the Data Protection Officer (DPO) has been proposed. This may be an individual person or a legal entity, public authority, service or other body that processes personal data on behalf of the data controller. It is advisable that the DPO is included from the beginning of the design of a TP program. A difference between our Spanish Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights (PPDGDR) and the European one, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is that the Spanish regulation mandates the certification of the DPO and, above all, lists the 16 specific situations in which it is necessary to have this role. In the case of TP, it is mandatory for healthcare centers that are legally obligated to keep medical records (within the timelines set out in the Law Patient Autonomy (LPA), except for physicians who work on an individual basis).25

At the European level, according to the GDPR, the psychiatrist will be responsible for documenting that consent was specifically provided (Article 7 of the GDPR, 2016).25 The safest option appears to be written consent, for which a computerized protocol would have to be designed, allowing clear identification of the user by means of electronic signature or double authentication processes, or by taking advantage of face-to-face presence in hybrid treatment models. Another option, although less safe legally, would be to record consent at the start of a videoconference, which would have to be stored and should include all the aspects mentioned above. Such consent should include the period of retention of personal data, based on the legally established timelines.5

For the use of videoconferencing, we recommend reviewing the availability of certifications (ISO 270001, ENS, AENOR) and security incidents, which can be consulted on the website of the National Cybersecurity Institute.26 They should also be privacy shields in place, and information should be encrypted to prevent unauthorized dissemination and include specific protocols for the detection of security incidents. Certification, privacy shielding and incident detection should be reviewed for storage systems, including those in the cloud. Some applications change these features in their paid version, so the guarantees offered by each subscription mode should be reviewed. There are guides published by various societies5,27 that provide general legal guidelines in this regard.

Ethical aspects of telepsychiatryThe Central Deontology Commission has issued a consultation report highlighting the need to update current ethical standards in the context of spectacular technological development, especially Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), and to consider whether these technologies can serve to optimize the use of resources and improve the distributive justice of the healthcare system by improving accessibility and equity.28 However, we should not forget that many users may have difficulties both in accessing the technology and in using it appropriately, whether for socioeconomic or cultural reasons. One proposal in this regard in the field of public health would be to facilitate supervised telemedicine consultations in rural health centers, where specialized consultations may be a considerable distance away. TP would also allow for greater dynamism in the professional response, avoiding transfers or absences from work or school.29

Definitions and formats of telepsychiatryIt is important to clarify that current TP is not limited to videoconferencing but encompasses many other services such as monitoring with apps, online questionnaires, the exchange of files such as reports, prescriptions and electronic prescriptions, and the computerized recording and collection of data in the medical record.

Broadly speaking, we can categorize three types of TP according to the classification proposed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)2,30:

- -

Synchronous: Those platforms that offer live interaction, in real time or live between psychiatrist and patient (e.g., video-consultations).

- -

Asynchronous: Those communication services between the psychiatrist and the patient that differ or may differ in the time between the emission and reception of the message (e.g., chats, e-mails or SMS).

- -

Telemonitoring: There is no direct communication between psychiatrist and patient, however, these services collect continuous information, often in real time, which can be assessed in a deferred or live manner by the psychiatrist or another member of the mental health team (e.g., apps, mHealth or Ecological Momentary Assessment or EMA).31

In this review we will focus on synchronous platforms, i.e. in real time or live via video call, although many technical concepts can be extrapolated to asynchronous platforms.

Formal and technical aspects of telepsychiatry: local hardware, software, and data exchange networkThe computer or mobile device: The vast majority of TP software is based on native applications or increasingly, on cloud or web services. Therefore, they require moderate multitasking processing power when having the browser-based teleconferencing, medical records and prescription platform running, but the required encryption of the platforms may require extra-work on the part of the processor. Considering these circumstances, ideally at least 2-core computers (e.g. Intel Core 2 Duo or higher, AMD Athlon X2 or higher) and 4 GB of RAM should be preferred as a minimum to ensure a smooth environment. All main computer storage drives (or any external memory) where any information related to the visits is stored must have some form of full encryption method in place. Storing sensitive data on commercial cloud services (Dropbox, OneDrive, Google Drive or similar) that are not hosted or supported and secured by each professional's workplace should be avoided. Mobile devices (such as smartphones and tablets) can also be used, but are less recommended for technical and security reasons.

The video camera (or webcam): Can be either external or internal, built into the monitor as laptops often have. The external ones allow greater flexibility of focus and positioning. However, given the advances in technology, a minimum requirement is that they have a resolution of 640×480 or higher, at a minimum speed of 30 frames per second (or FPS).32 It is convenient that the camera has a wide angle of focus, but at eye level, or zoom out so that the psychiatrist can appear from half torso up, and if there are two people in the room, they can also enter the same image. It is important that the camera allows the non-verbal language of the doctor and the patient to be evaluated. The environment and background behind the psychiatrist should be neutral and be accompanied by adequate lighting.

The audio device (microphone/headphones/speakers): Ideally, binaural headphones should be available to allow clear hearing. Although the tele-consultation can also be done through loudspeakers, at least 7kHz full duplex with echo cancelation, the latter can be a possibility in offices with certain privacy and soundproofing. There are no specific recommendations regarding the microphone to be used. It is also possible in most computers to connect an external microphone (stand, lapel, or others) that allow greater mobility and closer contact with the transmitter's voice, which can significantly improve audio quality. There are some external microphones that can be muted with a physical switch, which can be very useful in certain circumstances. There are different wired (serial port and USB) and wireless (Bluetooth) computer technologies where both headsets and microphones can be connected. Security parameters should also be taken into account for Bluetooth technology, as they can be intercepted, ideally opting for devices that support level 4 security with ECDH (Elliptic Curve Diffie-Helllman P-256) encryption.32

The video-consultation platform is the computer program or application that allows communication with the patient through video and audio.

In the scope of an Institution there is always the doubt of developing its own platform or contracting with one of the existing services. The cost of developing a proprietary platform is significant in comparison with the adaptability that can be offered by the various platforms currently available to suit your needs.32

As for the data exchange network via the Internet, a connection of at least 5 Megabytes (MB) per second both downstream and upstream with low latency rates, as well as stability, is recommended. The connection between the computer and the router should preferably be made via Ethernet cables (network) with 1000BASE-X standards to ensure the efficiency, security and stability of the connection,33 thus avoiding wifi connections whose stability and speed are influenced by more factors, including climatic ones. This bandwidth should be dedicated almost exclusively for the duration of the tele-consultation (thus avoiding technical problems).

In the event that the connection is interrupted or breached, an alternative contingency communication media plan should be in place to re-establish communication with the patient should something happen, such as access to a telephone and the patient's number. This plan should be communicated and tested prior to the start of the tele-consultation.34

Disorders approached through telepsychiatry- A.

Depressive and anxiety disorders:

There are several studies that compare face-to-face care with TP in different depressive and anxiety disorders, with no significant differences.35 This approach has been used both in PC and in mental health and social services, demonstrating an adequate level of clinical efficacy.36

A significant improvement in depressive symptoms has been demonstrated through TP intervention as measured by scores on the Hamilton Depression Scale and Beck Depression Inventory, regardless of the type of psychopharmacological treatment received. These results suggest that this intervention modality is comparable to face-to-face treatment.37

Patients suffering from certain anxiety disorders, such as agoraphobia, may particularly benefit from TP, especially in acute situations, avoiding the exacerbation of symptoms due to travel to outpatient clinics.36 In the case of simple phobias, virtual exposure scenarios have been proposed that show symptomatic improvement after three months of follow-up.35

- B.

Bipolar disorder (BD) and other affective psychoses:

The application of videoconferencing at the clinical level in the case of Bipolar Disorder (BD) can establish collaborative treatment models necessary for therapeutic management.38

Significant improvements in manic symptoms, depressive symptoms and behavioral disturbances, as well as in psychological quality of life, have been observed with TP programs for BD. However, no improvements have been observed in physical health or in subjective feelings of well-being, risk of self-injury or alcohol consumption, which would indicate that TP may be limited when certain symptoms are to be treated.38

- C.

Psychotic disorders:

In the case of schizophrenia, TP can be useful as it has been shown to improve adherence and maintain stability in response to treatment, filling the gap that exists for some patients’ access to psychiatric treatment.39 Among the aspects that benefit the most are patient's communication with attending staff, improvement in positive symptomatology, reduction in visits to the emergency room and reduction in average hospital stay.39

In addition, adequate levels of satisfaction have also been found in both patients and clinicians who have used TP in the therapeutic management of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

- D.

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD):

Establishing a therapeutic relationship with patients with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) can be particularly challenging. Internet technologies offer us a way to interact with patients who are reluctant or unable to attend for face-to-face clinical evaluation.40

It is worth noting that high levels of satisfaction have been evidenced in parents of patients with ASD who have used TP because despite the drawbacks in capturing nonverbal information in TP, this therapeutic modality may be more accepted by adolescents and patients with ASD.40

- E.

Substance use disorders:

The literature is very limited when it comes to TP in substance use disorders. In terms of effectiveness, however, there are no studies that consider TP to be inferior to face-to-face treatment. TP may be especially promising in the management of opioid dependence, although more randomized studies are needed.41

Telepsychiatry with children and adolescentsFrom the pioneering study carried out in 2003 by Nelson et al.42 in childhood depression, we have seen in recent years the appearance of randomized clinical trials with TP and comparative pre–post treatment studies on various disorders. Although mostly with small samples, these studies have shown promising results specifically in patients with ASD and moderate–severe behavioral problems, and have demonstrated that tele mental intervention with parents significantly reduced disruptive behaviors compared to treatment as usual,43 in patients with Attention Deficit Disorder.44 In general, the literature shows that a wide variety of disorders such as anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, tics and behavioral disorders have been successfully treated with TP in both children and adolescent populations.45

Despite not being implemented in our country, the use of TP in schools is an area of rapid growth in recent years in the United States, where it is gaining acceptance due to its cost-effectiveness and convenience for patients and families.46 A recent study that analyzed the use of TP in schools indicated that it was more efficient than face-to-face services, saving around 28h per month in travel time.47

Another of its main benefits lies in the reduction of parental requests for leave from work, as well as a reduction in children's absences from school, resulting in fewer canceled appointments compared to usual practice.46

Group telepsychiatryWith respect to the face-to-face model, the telematic group option may favor the inclusion of patients who would not usually attend group therapy due to incompatibility of schedules, difficulty in traveling to the place of therapy, symptoms specific to their illness or embarrassment to express their suffering in a face-to-face manner. In a telematic format, it is not advisable to have more than 10–12 people, since the possibility of interaction and bonding would be insufficient. It is necessary to order the interventions to avoid continuous interruptions. The connection should start 10–15min before, in order to assist those who, have technical problems. In the telematic format, the shyer participants may go unnoticed more easily, so therapists should make an extra effort to be aware of all participants. A climate of trust and a feeling of belonging to the group should be created.48

Telepsychiatry and researchWe can affirm that there are not many differences when carrying out clinical research projects between a face-to-face and a virtual context. A specific element in research using videoconferencing is that great care is required to maintain consistency in the technological conditions of the connection to ensure that the results can be extrapolated to other populations.49

A clear utility of TP is that it can decrease the variability of observations in clinical studies involving multiple centers. The use of a small number of remote centralized assessors, blind to any other elements of the protocol, can increase the reliability of the results, decreasing interobserver variability and reducing potential biases.

There is evidence that remote assessment of patients via videoconferencing in clinical trials by assessors blind to treatment and other elements of the research protocol can improve sensitivity and control for placebo response.50 This methodology has already been used successfully in terms of differentiating between an effective active drug and a placebo in clinical trials with hundreds of patients in both schizophrenia,51 and major depression.52

Despite all the advantages listed above, we should not forget that TP can present some difficulties and reluctance. In Table 1 we have summarized the main advantages and disadvantages of the application of TP in the management of mental illnesses.

Advantages and disadvantages of the use of Telepsychiatry in the clinical setting.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Telemedicine can be especially useful in the field of psychiatry since we do not need to perform a physical examination.2 | Difficult to implement in patients who are violent, unstable, impulsive, manipulative, or at immediate risk of suicide or at high risk of suicide or very dangerous |

| May be useful in patients who prefer to be treated at home, saving the need to visit an outpatient medical center. | Caution should be exercised when using it to assess a symptom profile that may be exacerbated by the use of technology. |

| Higher level of user satisfaction.12,13 | May not be useful in patients with auditory, visual, or cognitive deficits that limit the patient's ability to interact coherently with the technology used |

| Especially useful for patients residing in rural or isolated areas.17,19 | Difficult to use in the event that decisions have to be made against the patient's wishes involuntary treatment, decision to admit, etc.). |

| May improve response time for patients requiring urgent care.17 | Lack of experience and knowledge on the part of the professionals who must implement TP.34,53 |

| May be of choice in child and adolescent psychiatry.18,42–45 | Possible difficulty in adopting a correct therapeutic relationship.14,15 |

| It has demonstrated similar levels of reliability between TP and face-to-face consultations.11 | Patients need to have access to new technologies, which could increase inequality.23 |

| It has demonstrated its efficacy in different diseases (major depression, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, attention deficit disorder, eating disorders…).11,35–40 | Greater difficulties in safeguarding privacy and confidentiality.15 |

| Lower cost and transportation than face-to-face.14 | TP may have more difficulty in applying scales or instruments that require objective observational data.21 |

| Proved useful in geriatric population. | Reluctance on the part of professionals to implement TP services. |

| Access to technology by patients is similar to that of the rest of the general population. | There are great difficulties in integrating and implementing digital technologies in routine clinical practice in mental health. |

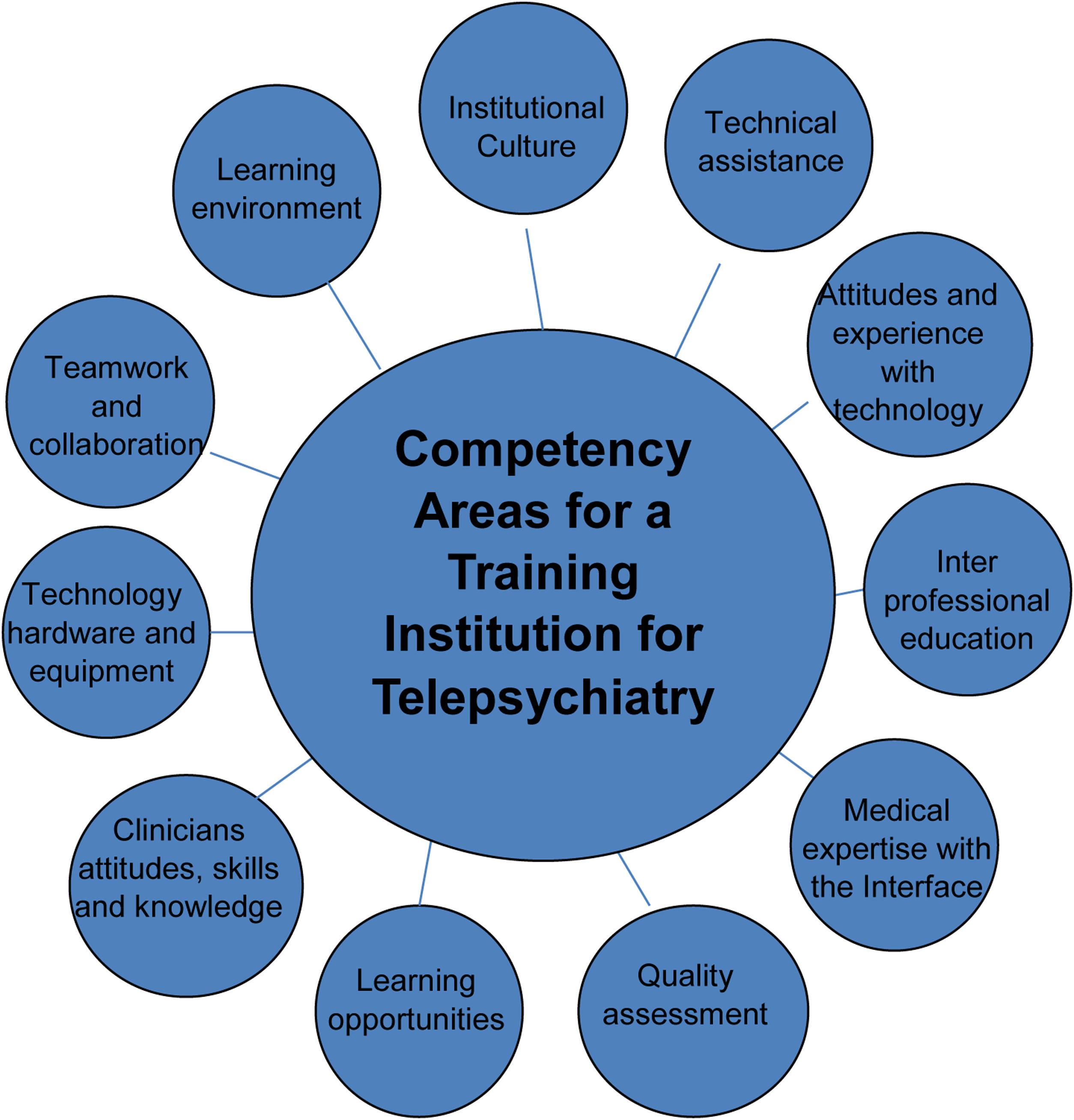

Any ambitious project that aims to implement a TP program with a minimum standard of quality in its application involves a training and communication plan. TP training should focus on four pillars summarized with the acronym AKAS: Awareness (to be aware of its existence and usefulness), Knowledge (to know what it is for and how it is carried out), Attitude (what are the best attitudes the physician should have to get the most out of it) and Skills (what communication skills we should have to put it into practice). For the elaboration of this section we have relied on the online TP tool developed by the American Psychiatric Association34 and on the survey elaborated by Zayapragassarazan in 2016.53 In Table 2 we summarize the main questions to be answered when we want to implement an ambitious training program while in Fig. 1 we point out the main skills and competencies to be developed in it.

AKAS (Awareness, Knowledge, Attitude and Skills) model for implementing training in Telepsychiatry.33,52

| Area of interest | Items evaluated |

|---|---|

| Awareness | Are we aware of the advantages of TP?Do we evaluate the possibilities for patients to be cared for by this method?Do we believe that TP is as effective as face-to-face care?Do we show anxiety or serious reluctance about the use of technology in the health care setting?Do we ask what degree of knowledge and use our patients have of information technologies? |

| Knowledge | Do we health professionals know how to implement TP?Have we received specific training to carry it out?Do we have experience that will allow us to solve the practical difficulties we will encounter? |

| Attitudes | What is our general attitude toward TP?Do we have personal drawbacks when it comes to putting it into practice?Do we demand that our decision-makers and managers develop programs to implement it?How do we propose to our patients that they can be cared for by this new modality? |

| Skills | What are the main skills that a practitioner who wants to start TP should have?Is it necessary to train any particular talent to be able to carry it out?Are there any personal conditions that make it inadvisable to implement TP approaches? |

Competency areas and skills that must be developed to improve the quality of Telepsychiatry.

With regard to communication, there are three areas on which we should focus our efforts: the technical staff (not only the physicians but the entire multidisciplinary team), the managers (both those responsible for the agenda and those responsible for clinical management) and the patients. If any of these three actors does not know that TP is being carried out in our service, then it cannot be properly implemented.

In conclusion, we can affirm that the COVID-19 pandemic has brought with it the possibility of developing and improving the use of TP in our country. Having had to use this service on a mandatory basis, as it has become the only method of communication we had with our patients, we have taken away our fear and discovered that it can become a powerful clinical tool in the health-care sector. TP has been shown to have similar levels of validity, efficacy and effectiveness to face-to-face care, which is why some experts point out that the enhancement of TP will be key in the future.53,54 In order to implement it properly, we must comply with a minimum of audiovisual technical means and good connectivity, without forgetting that this technique must take into account aspects related to privacy and security. TP opens up new possibilities in the field of care and treatment of most mental conditions, being especially useful in the child and adolescent area, in the field of research and in the care of patients living in rural and isolated areas.

In the light of the review, there is a need for a training plan, including technical, regulatory and ethical aspects, to resolve the doubts of providers and users and to give us the necessary impetus to advance in this clinical field in our country.

Funding statementFunding for open access charge: Universidad de Granada/CBUA.

Conflict of interestL. Gutiérrez-Rojas has received consultancy and/or lecture honoraria from Lundbeck, Pfizer, Novartis, Janssen, Neuraxpharm, and Otsuka in the last 5-years, none of them with direct relation to this work. IG has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following identities: Angelini, Casen Recordati, Janssen Cilag, and Lundbeck, Lundbeck-Otsuka, Luye, SEI Healthcare, FEDER, Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement (2017SGR1365), CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI16/00187, PI19/00954).

The authors would like to thank the collaboration of Spanish Society of Psychiatry.