The DSM-5 and ICD-11 classifications, the latter still under development, are aimed at harmonizing the diagnoses of mental disorders. A critical review is presented in the issues that can converge or separate both classifications regarding bipolar disorders, and those conditions –included in depressive disorders–with special relevance for bipolar (e.g. major depressive episode). The main novelties include the incorporation of dimensional parameters to assess the symptoms, as well as the sub-threshold states in the bipolar spectrum, the consideration of new course specifiers such as the mixed symptoms, the elimination of mixed episodes, and a more restrictive threshold for the diagnosis of hypo/mania.

The most noticeable points of convergence are the inclusion of bipolar II disorder in ICD-11 and the additional requirement of an increase in activity, besides mood elation or irritability, for the diagnosis of hypo/mania in both classifications. The main differences are, most likely keeping the mixed depression and anxiety disorder diagnostic category, maintaining bereavement as exclusion criterion for the depressive episode, and maintaining the mixed episode diagnosis in bipolar disorder in the forthcoming ICD-11.

ConclusionSince DSM-5 has already been published, changes in the draft of ICD-11, or ongoing changes in DSM-5.1 will be necessary to improve the harmonization of psychiatric diagnoses.

Las clasificaciones DSM-5 y CIE-11, esta última en elaboración, pretenden armonizar los diagnósticos de los trastornos mentales. En este artículo hacemos una revisión crítica de los puntos que pueden aproximar y aquellos que pueden dificultar la convergencia de los trastornos bipolares, así como de aquellas condiciones clínicas incluidas dentro de los trastornos depresivos con especial relevancia para los trastornos bipolares (p. ej., episodio depresivo mayor). Las principales novedades agregadas comprenden la incorporación de parámetros dimensionales para la evaluación de los síntomas, la posibilidad de diagnosticar cuadros subumbrales del espectro bipolar, la consideración de nuevos especificadores de curso como los síntomas mixtos, la desaparición del diagnóstico de episodio mixto, y el aumento del umbral para el diagnóstico de hipo/manía.

Las convergencias destacables son la inclusión del trastorno bipolar II en la CIE-11 y la exigencia adicional, además de la euforia o la irritabilidad, de un aumento de la energía o de la actividad para el diagnóstico de hipo/manía en ambas clasificaciones. El mantenimiento del diagnóstico de trastorno mixto ansioso-depresivo, del duelo como criterio de exclusión de depresión mayor, o el diagnóstico de episodio mixto en el trastorno bipolar, son algunas de las principales divergencias en la versión beta de la CIE-11 respecto al ya editado DSM-5.

ConclusiónDado que el DSM-5 ya ha sido publicado, serán necesarios cambios en el borrador de la CIE-11 o modificaciones del DSM-5.1 para armonizar los diagnósticos psiquiátricos.

After more than 15 years without significant changes in the classifications of mental and behavioural disorders, the new Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-V has finally been published,1 while the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) is underway and its publication is scheduled for 2017. Although these two are not going to coincide in their publication dates, the intention to harmonise the diagnoses in both classifications is real.2

Controversy and arguments have accompanied the DSM-V both during its preparation and at the moment of its official publication, with the criticisms received from the National Institute of Mental Health perhaps being the most notable.3

Just as was specified in its initial objectives,4 priority was given to the clinical usefulness of the diagnoses, even at the cost of not finally improved their validity. Other objectives, such as supporting the changes with respect to the DSM-IV based on scientific evidence, were only partially fulfilled. This has been the object of criticism, as much for seeming a priori like a fatuous objective given the current limitations of scientific knowledge,5 as for the final result, which is overly conservative, prioritising pragmatism to the detriment of a more scientific classification.6 The final preparation process was open to both the public and the professionals through processes of draft revision and suggestion submission via the website of the American Psychiatric Association. We are unaware of what final percentage of these proposals–indiscriminately evaluated, heedless of their origin–entered in the ultimate debate. Before publication of this update, field studies were likewise carried out to evaluate the viability, clinical usefulness, reliability and validity of criteria proposed.7–9 The end result is that the DSM-V, like other classifications, is only a faithful reflection of cultural system from which it emerges, adapted to medical insurance and reimbursement systems and to regulatory systems in force in the USA.10

The World Health Organisation, in its participation in the process of updating its classification of disorders in mental health and in behaviour in which it is immersed, has requested the collaboration of experts and users through the webpage http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/revision/en/.

This is not the first time that there has been an attempt to homogenise the two classifications; and, now that the DSM-V has finally seen the light, the task seems difficult and voices have even been raised against the fact that it has finally happened.11

In this review article, we analyse the points that can align and those that can raise obstacles to the convergence of bipolar disorders and the disorders–included within the depressive disorders–that have special relevance for bipolar disorders (for example, major depressive episode).

MethodsWe carried out a review of the DSM-V diagnostic criteria. In the case of the ICD-11, we reviewed the information contained in the beta version of the classification (http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd11/browse/l-m/en, accessed June 2014), as well as in the special supplement2 and various articles focusing on the subject in the journal World Psychiatry. Consequently, insofar as the ICD-11, the end product might change substantially from what is presented in our review.

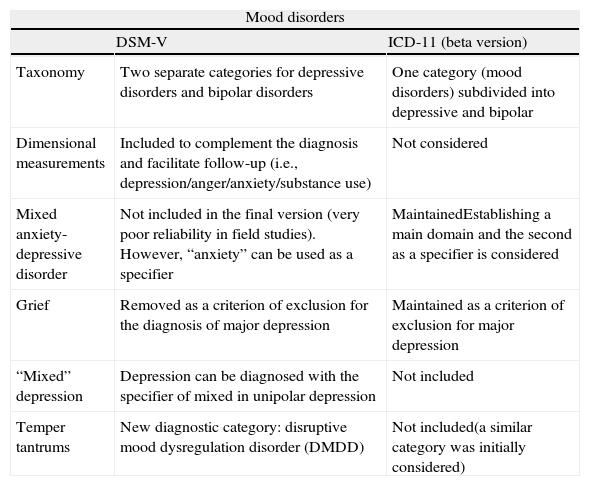

DSM-V, ICD-11 and mood disordersTable 1 offers a summary of the main differences and similarities between the DSM-V and the beta version of the ICD-11 with respect to mood disorders in general. How the diagnoses in the two classifications are organised already offers the first divergence, which is perhaps the reflection of differences in the scientific environment as to the proper place for the patients that present these complex disorders and the way help for them should be organised.12 In their initial drafts both the DSM and the ICD separated the depressive bipolar disorders. However, now that the DSM-V has been published, the beta version of the ICD-11 offers a single diagnostic category, “mood disorders”, subdivided into bipolar disorders and depressive disorders. The DSM-V creates two differentiated sections, one for “depressive disorders” and another for “bipolar and related disorders”.

Main differences and similarities between the DSM-V and the beta version of the ICD-11: mood disorders in general.

| Mood disorders | ||

| DSM-V | ICD-11 (beta version) | |

| Taxonomy | Two separate categories for depressive disorders and bipolar disorders | One category (mood disorders) subdivided into depressive and bipolar |

| Dimensional measurements | Included to complement the diagnosis and facilitate follow-up (i.e., depression/anger/anxiety/substance use) | Not considered |

| Mixed anxiety-depressive disorder | Not included in the final version (very poor reliability in field studies). However, “anxiety” can be used as a specifier | MaintainedEstablishing a main domain and the second as a specifier is considered |

| Grief | Removed as a criterion of exclusion for the diagnosis of major depression | Maintained as a criterion of exclusion for major depression |

| “Mixed” depression | Depression can be diagnosed with the specifier of mixed in unipolar depression | Not included |

| Temper tantrums | New diagnostic category: disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) | Not included(a similar category was initially considered) |

In Section III of the DSM-V there is the possibility of assessing the various transversal psychopathological domains in different diagnostic categories, as a complement to the initially assigned category diagnosis or to help in therapeutic follow-up. First-level evaluation (completed by the patients themselves or by caregivers) covers different domains such as depression, anger, anxiety, somatic symptoms and substance use, among others; a 23-item questionnaire is filled in, taking symptom seriousness and frequency into consideration as well. At the second level, a clinician should handle the assessment, offering various instruments to evaluate depressive, manic or psychotic symptoms. At the moment, adopting any dimensional measurements seems out of consideration for the future ICD-11.13

Mixed anxiety-depressive disorderAlthough the initial draft of the DSM-V included mixed anxiety-depressive disorder as a new category, in the final version it has disappeared. To the previously received criticisms,14 one can add the really poor reliability results obtained for this diagnostic category in field studies,7 which may explain its final elimination. In contrast, the specifier “with anxiety symptoms” is included, both for depressive disorders as well as for bipolar disorders. This possibility will undoubtedly reduce high comorbidity rates–perhaps artefactual–between anxiety and mood disorders, while allowing necessary assessment of signs of anxiety in bipolar disorder, which sometimes contribute to emotional decompensation.15 The diagnosis of mixed anxiety-depressive disorder, however, is still widely used by the set of professionals that deal with mental health problems around the world, which would explain its presence in the current ICD-10. For the ICD-11, there has been a proposal to code the disorder predominantly with a specifier of the opposite aspect,16 a solution adopted in the DSM-V in the end for depression, but not for anxiety.

Elimination of grief as a criterion for exclusion in major depression episodeOne of the most disputed questions has arisen around the removal of grief as a criterion for exclusion for the diagnosis of major depressive episode in the DSM-V. Those who introduced grief in the DSM-IV did so to avoid false positives (normal grief). Its withdrawal rekindles the fear that the DSM-V makes it easier to consider as pathologies (and consequently susceptible to being treated) human conditions that are not in and of themselves pathological, with objectives not strictly related to good clinical practice.14 However, its advocates argue that, in the case of individuals in situations of grief who present depressive symptoms graves, the possibility of receiving a diagnosis of major depression gives them the chance to be treated appropriately and for there to be the consequent reimbursement of expenses in specific healthcare systems (which does not necessarily imply drug treatment). Arguments such as these distance the DSM from the orthodoxy of scientific classifications, for good or for bad.

In two articles on the subject, some of the authors involved in the ICD-10 revision process declared that “this could be one of the points of disagreement that make it difficult to harmonise the two classifications” and argued that there was no scientific evidence to justify the removal of grief.17,18

Hypomanic symptoms in major depressionIn the DSM-V, including the specifier “with mixed symptoms” is considered for depressive episodes in recurrent unipolar major depression. Consequently, the diagnosis of unipolar depression with subsyndromal hypomanic symptoms can be made, without considering that the patient presents a bipolar disorder. All of these changes have been considered in reviewing the ICD-10,19 but they have not been incorporated into the draft, at least not in its present phase.

Temper tantrumsAlthough this concept was not included in the chapter of the bipolar disorders in the end, but in that of depressive disorders, we are going to briefly comment on the addition of a new diagnostic category for children. It is relevant that its origin is related to the earlier diction of an increase in childhood bipolar disorder diagnoses in the USA,20 and seems to be an attempt to prevent excess diagnosing in children that presumably do not suffer bipolar disorder and run the risk of being erroneously diagnoses. It is called “disruptive mood dysregulation disorder”. It can be diagnosed in children aged under 10 years that present frequent and severe non-cyclical tantrums together with chronic persistent irritability, produced in more than 1 setting, for at least a year. The ICD-11 raised the possibility of a category with very similar criteria, el “disruptive mood dysregulation with dysphoria disorder”,21 but it does not appear as such in the latest draft of the document. An epidemiological study reveals the difficultly of distinguishing this new category from oppositional defiant disorder and from behaviour disorder, questions its diagnostic stability, and finds no association with family history of mood disorders or anxiety. The authors’ conclusion is that they doubt that this new diagnosis will be useful in the clinical population.22 The low diagnostic reliability of this category has been confirmed in field studies.9

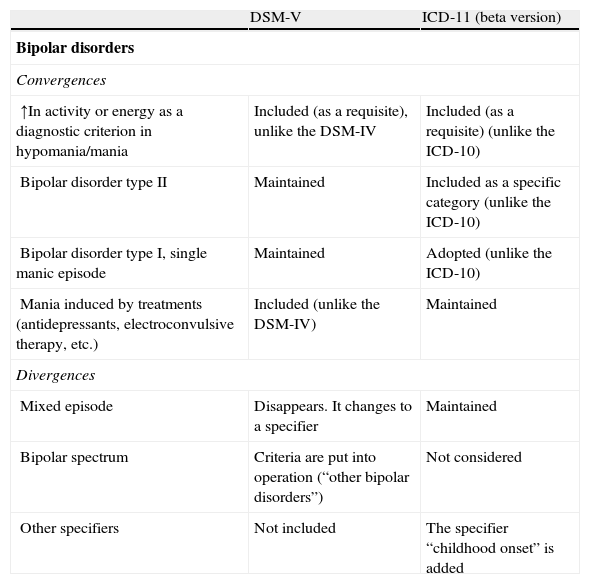

DSM-V, ICD-11 and bipolar disordersTable 2 summarises the main differences and similarities between the DSM-V and the beta version of the ICD-11 with respect to bipolar disorders.

Main differences and similarities between the DSM-V and the beta version of the ICD-11: bipolar disorders.

| DSM-V | ICD-11 (beta version) | |

| Bipolar disorders | ||

| Convergences | ||

| ↑In activity or energy as a diagnostic criterion in hypomania/mania | Included (as a requisite), unlike the DSM-IV | Included (as a requisite) (unlike the ICD-10) |

| Bipolar disorder type II | Maintained | Included as a specific category (unlike the ICD-10) |

| Bipolar disorder type I, single manic episode | Maintained | Adopted (unlike the ICD-10) |

| Mania induced by treatments (antidepressants, electroconvulsive therapy, etc.) | Included (unlike the DSM-IV) | Maintained |

| Divergences | ||

| Mixed episode | Disappears. It changes to a specifier | Maintained |

| Bipolar spectrum | Criteria are put into operation (“other bipolar disorders”) | Not considered |

| Other specifiers | Not included | The specifier “childhood onset” is added |

For the diagnosis of mania or hypomania, the DSM-V includes the criteria of “increase in energy or goal-directed activities compared with the habitual in the subject”–just as various authorities in the field demand.23–25 However, it is not an independent criterion but is added to mood elevation. Consequently, the threshold for diagnosis is raised, probably improving specificity but reducing sensitivity. Increased activity is also included as a diagnostic criterion in the beta version of the ICD-11.

The diagnosis of bipolar disorder and bipolar spectrum disordersTwo of the main differences between the DSM-V and the ICD-10 refer to the lack of recognition bipolar disorder type II in the latter, as well as not considering patients with a single manic episode or patients with unipolar mania within bipolar disorder type I. Both these differences seem to have been overcome in the beta version of the ICD-11, in which bipolar disorder type II is indeed defined, and where bipolar disorder type I is defined by the presence of “1 or more mania or mixed episodes” over the course of the subject's life.

Likewise, the DSM-V acknowledges for the first time that patients without previous history of bipolar disorder under antidepressant treatment (drugs, electroconvulsive therapy, etc.) who develop a manic syndrome of sufficient intensity and duration can be considered as patients con bipolar disorder. This will undoubtedly help to coincide with the ICD-11.26

The DSM-V introduces criteria for the diagnosis of clinical states belonging to the bipolar spectrum that were previously unspecified and consequently undiagnosable. For example, under the heading “Other specific bipolar disorders and related conditions”, the possibility of identifying individuals that have had major depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes is included for cases in which they either do not fulfil the required number of hypomania symptoms, or present sufficient symptoms for a diagnosis of hypomania but it lasts only 2 or 3 days. There are other situations contemplated within the spectrum, such as episodes of hypomania without antecedents of depression, or short-lasting cyclothymia. This reduction of the threshold for the diagnosis of bipolar spectrum disorders has produced both negative responses27 and positive responses among the experts.28 Within this section for the subsyndromal symptoms, it is worthwhile noting the inclusion−in the diagnostic category of “depressed conditions not classified in another place”−of patients that have recovered from a major depressive episode but currently suffer symptoms that do not fulfil the criteria for a depressive episode. Likewise, among the headings “that require further studies”, that of “depressive episodes with short-lasting hypomanias” is included.

Insofar as the decisions that will be made for the ICD-11, some authors involved in the process of review doubt the scientific founding of the concept of spectrum, so they reject including it in the classification.26

However, in this review of both classifications it should be pointed out that the possibility of a diagnosis of mixed episode for bipolar disorders is maintained in the current draft of the ICD-11. This is one of the most relevant changes that have been produced in this field in the DSM-V.

Course specifiersOne of the most-commented novelties as to emotional disorders in the DSM-V refers to the disappearance of the category of mixed episode in bipolar disorders. The mixed nature of affective episodes becomes a course specifier. It can be applied to both depressive episodes of bipolar disorder and unipolar depression and to both manic episodes as well as hypomanic. In spite of recognising the need to change the previous strict criteria, the decision to exclude common symptoms such as irritability, distractibility or psychomotor agitation has been criticised as not very scientific and as lacking validity.29 The reviewers of the ICD-10 doubt the diagnostic usefulness and are considering keeping the criteria of mixed episode unchanged and not adopting the criteria of the DSM.19

It is also worth stressing, with reference to course specifiers, that there has been an addition of seasonal pattern for its application in hypomania/mania episodes as well (previously it was only considered for depressive episodes).

Changes not made in the DSM-VIn the last few years, various groups of experts and scientific associations (i.e., the International Society for Bipolar Disorders [ISBD]) had made several proposals designed to define the concept of bipolar spectrum, as well as suggestions aimed at improving diagnostic criteria or different aspects for better characterisation of the patient with con bipolar disorder. These have, in part, been included in the manual. We highlight below the proposals rejected that seem most relevant to us:

- •

The criterion of length of hypomanic episode is not modified. Experts in different sectors had recommended shortening the time required for the diagnosis.25,30 In exchange, it has been accepted that patients with short-lasting symptoms can fit into the category of “other bipolar disorders”, as has been commented earlier.

- •

Bipolar depression is not distinguished from unipolar. It should be mentioned that the previous model suggested by the ISBD to help to differentiate bipolar depression I from unipolar depression31 does not seem to have found the support need for incorporation into the diagnostic criteria.

- •

The diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder has not been eliminated, as had also been proposed previously.32 In contrast, it is still included in the section of “Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders”. The new criteria attempt to be somewhat more restrictive by requiring the presence of affective symptoms during the greater part of the course of the disorder. However, the final lack of an objectively based temporal criterion will probably end up perpetuating the ambiguity of the DSM-IV.

- •

Concerning the course specifiers, some authors had previously suggested the addition of aspects such as early onset or predominant polarity, given that they differentiate diagnostic subgroups and affect prognosis and treatment.33 However, in the ICD-11 it does indeed seem that the specifier of childhood onset is considered.34

Before the manual was published, the results of the field studies carried out in the USA and Canada were disclosed. With respect to the disorders analysed in this review, agreement in diagnosis is moderate35 for bipolar disorder type I (kappa: 0.56), somewhat less for type II (kappa: 0.40) and even lower for major depression (kappa: 0.28). It should be noted that the reliability of the new categories proposed, along with that of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder in childhood, is low (kappa: 0.25).

ConclusionsThe objective formulated by the scientific community of combining and homogenising the criteria for the two principal classifications of mental illness is legitimate and necessary.

In this review of the new proposals for affective disorders we have summarised the changes established in the DSM-V and have indicated the possible guidelines that will probably continue to be followed in the future ICD-11.

Without a doubt, one of the main innovations is produced in the chapter on valuation of mixed symptoms as a course specifier, which has to be researched as to its prevalence, affect on prognosis and treatment response. Some authors have expressed their fear that it might facilitate errors in diagnosing bipolar disorder.36

In our opinion, including subthreshold symptoms and other disorders considered within bipolar spectrum disorder would make it possible to improve and expand the scant current research taking place in this controversial but important field. We feel it would also enable optimising treatment of patients that are currently not identified or do not receive appropriate treatment.

The data on the reliability of the diagnoses confirm the limitations of these criteria, perhaps partially because psychiatric diagnosis is a continual process that often cannot be performed based on a single interview.37 There are other variables that the clinician has to bear in mind in the diagnostic process,33 such as family antecedents or early onset of affective episode in the case of bipolar disorders. Taking these aspects into consideration, along with the diagnostic criteria proposed, significantly increases diagnostic reliability.38,39

We would like to emphasise the distance there is between some of the criteria and modifiers present in the DSM-V and the empirical evidence. And what is worse: and in clinical practice. Consequently, if we take, for example, the case of assessing the risk of suicide, two of the markers of risk most solidly used by the clinicians–and backed by the literature–are the suicide death of a 1st degree relative and personal antecedents of suicide attempts. Neither one nor the other – we insist, sufficiently based on evidence–is included in the DSM, although it does contain modifiers totally lacking evidence behind them, such as the little prognostic or therapeutic impact of the “postpartum” marker in bipolar depression.33

The ICD-11 and the future revisions of the DSM-V in the field of bipolar disorders should be more open to incorporating new indicators and markers that help not only to increase the validity of the diagnoses, but also to improve the prediction of patient response to treatments. The advances that have been produced in the last decade in neurobiology, neuroimaging and genetics have not, in the end, been incorporated as criteria to help diagnosing in the DSM-V classification. Furthermore, we do know to what extent these advances will be incorporated in successive revisions–we should remember that it was created to become a “living document”–or in the coming ICD-11. Probably, as Kapur40 states, this is still impossible and it will be necessary to introduce some changes in research methodology to find a concept of disease (for psychiatric illnesses) that is stable and biologically valid that will make it possible to have biological tests with clinical usefulness to complement our conventional classifications.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: de Dios C, Goikolea JM, Colom F, Moreno C, Vieta E. Los trastornos bipolares en las nuevas clasificaciones: DSM-5 y CIE-11. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2014;7:179–185.