Inter-rater agreement is a crucial aspect in the planning and performance of a clinical trial in which the main assessment tool is the clinical interview. The main objectives of this study are to study the inter-rater agreement of a tool for the assessment of suicidal behaviour (Brief Suicide Questionnaire) and to examine whether the inter-examiner agreement when multiple ratings are made on a single subject is an efficient method to assess the reliability of an instrument.

MethodIn the context of designing a multicenter clinical trial, 32 psychiatrists assessed a videotaped clinical interview of a patient with suicidal behaviour. In order to identify those items in which a greater level of discordance existed and detect the examiners whose ratings differed significantly from the average ratings, we used the DOMENIC method (Detecion of Multiple Examiners Not in Consensus).

ResultsInter-rater agreement was between poor (<70%) to excellent (90–100%. Inter-rater agreement in Brugha's list of threatening experiences ranged from 75.5% to 100%; in the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale was 82.58%; in Beck's Suicidal Intent Scale, ranged from 67.5% to 97%; in Beck's Scale for Suicide Ideation, ranged from 63.5% to 100%; and in the Lethality Rating Scale was 88.39%. On the whole, the level of agreement among raters, both in general scores and in particular items, was appropriate.

ConclusionThe proposed design allows the assessment of the inter-rater agreement in an efficient way (only in one session). In addition, regarding the Brief Suicide Questionnaire, inter-raters agreement was appropriate.

El acuerdo entre-examinadores es un aspecto fundamental en la planificación de cualquier trabajo de investigación donde la principal herramienta diagnóstica es la entrevista clínica. El objetivo de este estudio es valorar el acuerdo entre-examinadores de un instrumento de evaluación de la conducta suicida (Protocolo Breve de Evaluación del Suicidio) utilizando las valoraciones de múltiples observadores en una sola sesión.

MétodoDurante la fase piloto de un estudio clínico multicéntrico centrado en la monitorización de intentos de suicidio, 32 examinadores evaluaron el vídeo de la entrevista clínica a un paciente simulado con conducta suicida. Para identificar los ítems en los que existía una mayor discordancia y a los examinadores cuyo criterio se alejaba más del acuerdo general, se utilizó el método DOMENIC (Detection Of Multiple Examiners Not In Consensus).

ResultadoEl acuerdo interexaminadores osciló entre pobre (<70%) y excelente (90–100%). En la Escala de Acontecimientos Vitales Estresantes el nivel de acuerdo osciló entre 48,4 y 97%; en la escala Problemas Psicosociales del DSM-IV, entre 75,5 y 100%; en la Escala de Evaluación de la Actividad Global fue de 82,58%; en la Escala de Intencionalidad Suicida, osciló entre 67,5 y 97%; en la Escala de Ideación Suicida, entre 63,5 y 100% y en la escala de Letalidad del Intento de Suicidio fue de 88,39%. En general, los examinadores mostraron un nivel de acuerdo adecuado tanto en las puntuaciones globales de cada escala como en cada ítem en particular.

ConclusionesEl diseño propuesto permite evaluar el acuerdo entre-examinadores de una forma eficiente (en una única sesión). Además, con respecto al Protocolo Breve de Evaluación del Suicidio, el acuerdo entre-examinadores fue apropiado.

Suicidal behaviour is the main cause of health resources use and mortality worldwide, especially among young people,1 and is a public health priority for the European Union. Suicidal behaviour (ideation, attempts, completed suicide) is heterogeneous due to the complex interaction of genetic, biological, psychological and environmental factors.2,28 Research on suicidal behaviour is limited by the difficulties involved in evaluating these aspects, which is why it is often studied as subordinated to the diagnosis of axis I (affective disorders and substance dependence) or axis II (border-line personality disorder) without specific assessment tools, when its clinical and health impact makes it deserve to be treated as an independent nosological entity.3

The gold standard for assessing suicidal behaviour is currently clinical assessment.4 However, using protocols and scales has proven very useful in improving the way information is documented and in increasing the thoroughness of clinical evaluation.5 The fact that clinical protocols and scales are used can also be of legal value and serve as a basis for making clinical decisions.6,7 Some recent studies, however, have revealed that the documents that accompany suicidal behaviour assessment are deficient in our environment.8,9 The Spanish group for suicidal behaviour research (GEICS is the Spanish acronym), aware of this situation, has designed a brief suicide assessment questionnaire, which includes the most widely used scales to assess the range of suicidal behaviour, from ideation up to suicide attempts,9 and examines the most important risk and protective factors (Appendix A).

To construct the brief questionnaire for suicide assessment, we have used the (preferably self-administered) scales most utilised in the literature of the past 40years of suicidology. We have also used questions that encompass the socio-demographic factors that have the best descriptive and predictive capability.7

One of the essential requirements for assessment tools is their reproducibility.10 This notion overlaps with that of agreement, and is used interchangeably to talk about consistency measures (reliability, reproducibility, repeatability), which refer to the agreement between several measurements in which none are the “correct” ones, and conformity measures (validity, accuracy), which refer to the agreement between one measurement and another acting as a reference.11 The prototype design for putting inter-rater reliability to test is to use a small number of independent raters (generally 2) who evaluate a large sample of subjects (more than 30). The reliability is measured using Kappa coefficients, the weighted Kappa or interclass correlation coefficient, based on whether the type of tool is to be evaluated is a nominal qualitative, ordinal qualitative or quantitative scale.12–16 Using these indexes requires a greater sample from a single subject to perform the reliability study appropriately, given that it is impossible to calculate the chance agreement with samples from a single patient. Its statistical power depends as much on the number of raters as of subjects, which means a very significant limitation for resources.17

To estimate the inter-rater agreement of the instrument for assessing suicidal behaviour, we used the strategy of a single case evaluated by multiple researchers. To do so, we used the method proposed by Cicchetti et al.,17 which allows you to generate indexes (that can be interpreted clinically and statistically) that permit assessing the overall rater agreement for each of the items in the scales. It also allows you to identify the raters who diverge from the overall agreement global (understood to be the mean score, given that a previous standard pattern is not assumed).

MethodRatersIn this study, 32 raters−psychiatrists and clinical psychologists with at least 2years of training–participated. They assessed a video-recorded clinical interview of a prototype case, recorded in a single session. Before the interview, they received a brief explanation of the tool and each of the scales it included. This audiovisual support has been used in the evaluation of the reliability of assessment tools in psychiatry18 and, although it generally presents lower agreement than clinical histories, it is closer to reality and is more economical than using multiple interviews repeated individually.19

The interview was carried out by 2 of the study participants (LG and JAG). By using this system, we attempted to minimise the factors related to the interview and to the patient that affect any reliability study, given that having a sample from a single patient makes this source of variability disappear.20 Identifying the factors related to the raters was one of the study objectives.

Measurement toolsThe different investigative groups designed an assessment questionnaire that examined the following suicidal behaviour-related variables: triggers (stressful life events, psychosocial problems), functionality (previous activity level), objective circumstances related to the suicide attempts, characteristics of suicidal ideation and lethality of the suicide attempt. In addition to examining clinical and socio-demographic data, our brief questionnaire (Appendix A) included the following tools, all translated to Spanish6:

List of threatening experiences (LTE)21This is an inventory examining the life events experienced by the patient in the last 6months. It consists of 12 dichotomous items that allow only 2 responses (present/absent).

DSM-IV-TR. Psychosocial problems22Using this tool, we gathered information on the psychosocial and environmental problems that had been present in the 6 previous months, as described in the DSM-IV (APA, 2000).

Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) is a tool administered by others, proposed by the DSM-III-R (APA, 1987),23 which evaluates the subject's general activity level in the psychosocial, social and work environments. The scores on this scale vary from 0 to 100, in 10-point intervals. The scale is scored based on the overall activity before the suicide attempt.

Beck's Suicide Intent Scale (SIS)24This other-administered tool to assess suicide intent (SI) characteristics consists of 2 subscales. The first groups the objective circumstances in which the suicide attempt was carried out; the second evaluates the patient's attitude towards life and death and how the patient sees this attempt. For this study, we used the first section, which examines the objective circumstances related to the intention of suicide attempts.25 This section comprises 15 items with a value from 0 to 2. In the studies performed to validate the scale, the measurement of the scores for highly serious SI was 16.3; for SI of average seriousness, the score was 10.1 and for low seriousness, 6.7.25 In a later study by Baca-García et al.,7 a cut-off point of 11 was established for distinguishing the patients who, following the suicide attempt, required admission to a psychiatric unit from those who did not need such an admission.

Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI)26This is a scale that quantifies and assesses the seriousness of suicidal thought, or degree of seriousness and intensity with which someone is thinking about killing themselves. It is a scale of 19 items that have to be filled in by a rater in a semi-structured clinical interview. Divided into 4 sections, it gathers a series of characteristics related to attitude towards life/death, suicidal thoughts or desires, planning the suicide attempt and performing the planned attempt. In the last section, previous suicide attempts are examined. There are 3 alternative answers for each item, indicating an increasing degree of seriousness and/or intensity of the suicidal intentionality.

Lethality Rating Scale27The suicide attempt method used was coded according to the Lethality Rating Scale and Method Attempt Coding (LRS), which evaluates the various methods utilised and also examines the medical consequences of the attempt.

Statistical analysisWe based the process followed for our statistical analysis on the method proposed by Cicchetti et al.16 In it, global agreement is defined according to the partial agreement levels (the shorter the distance between scores, the greater the agreement). Specifically, the following indexes were calculated:

Normal overall level of inter-rater agreement. This measurement indicates the global agreement of all the raters. The reference values for its interpretation are the following: excellent agreement (a score of 90–100), good (80–89), weak (70–79) and poor agreement (less than 70).

We found the agreement level for each rater individually. To do so, the raters with the same degree of agreement were grouped together and we calculated the clinical and statistical evaluation of the agreement level of each of the raters, using the agreement index, Z score (that indicates the deviation of each rater with respect to the consensus value, in this case the average of the scores).

To identify the items for which there was greater discordance and the raters with a low inter-rater reliability, we used the Detection of multiple examiners not in consensus (DOMENIC)17 method.

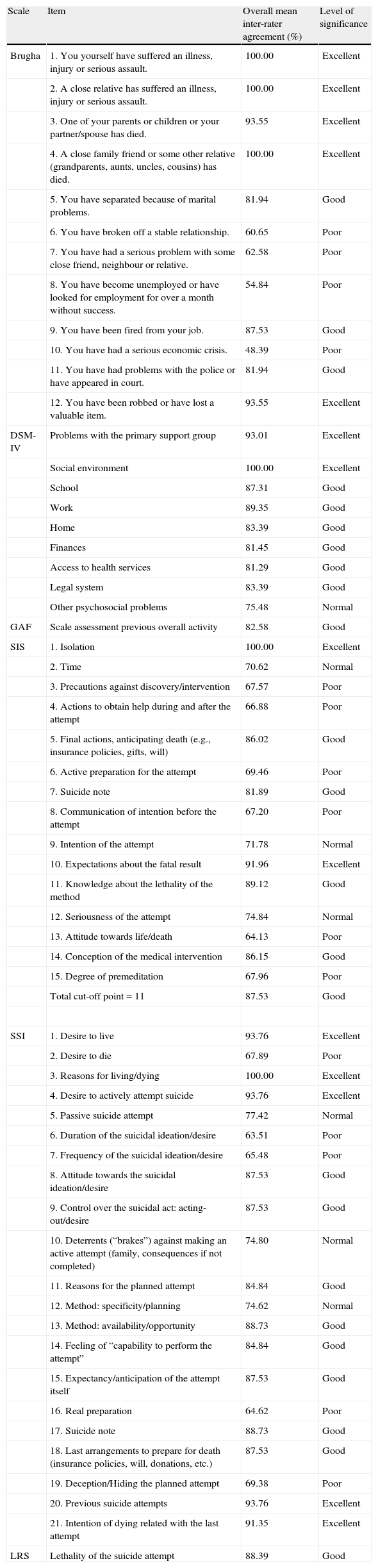

ResultsStressful life eventsThe overall mean for inter-rater agreement for each of the items ranged from 48.4% to 97% (Table 1). The agreement level principally fell between good (80%–89%) and excellent (90%–100%), except for the items 6, 7, 8 and 10 (6. You have broken off a stable relation; 7. You have had a serious problem with some close friend, neighbour or relative; 8. You have become unemployed or have looked for employment for over a month without success; and 10. You have had a serious economic crisis.) (Table 2).

Agreement on the various items of each assessment tool.

| Scale | Item | Overall mean inter-rater agreement (%) | Level of significance |

| Brugha | 1. You yourself have suffered an illness, injury or serious assault. | 100.00 | Excellent |

| 2. A close relative has suffered an illness, injury or serious assault. | 100.00 | Excellent | |

| 3. One of your parents or children or your partner/spouse has died. | 93.55 | Excellent | |

| 4. A close family friend or some other relative (grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins) has died. | 100.00 | Excellent | |

| 5. You have separated because of marital problems. | 81.94 | Good | |

| 6. You have broken off a stable relationship. | 60.65 | Poor | |

| 7. You have had a serious problem with some close friend, neighbour or relative. | 62.58 | Poor | |

| 8. You have become unemployed or have looked for employment for over a month without success. | 54.84 | Poor | |

| 9. You have been fired from your job. | 87.53 | Good | |

| 10. You have had a serious economic crisis. | 48.39 | Poor | |

| 11. You have had problems with the police or have appeared in court. | 81.94 | Good | |

| 12. You have been robbed or have lost a valuable item. | 93.55 | Excellent | |

| DSM-IV | Problems with the primary support group | 93.01 | Excellent |

| Social environment | 100.00 | Excellent | |

| School | 87.31 | Good | |

| Work | 89.35 | Good | |

| Home | 83.39 | Good | |

| Finances | 81.45 | Good | |

| Access to health services | 81.29 | Good | |

| Legal system | 83.39 | Good | |

| Other psychosocial problems | 75.48 | Normal | |

| GAF | Scale assessment previous overall activity | 82.58 | Good |

| SIS | 1. Isolation | 100.00 | Excellent |

| 2. Time | 70.62 | Normal | |

| 3. Precautions against discovery/intervention | 67.57 | Poor | |

| 4. Actions to obtain help during and after the attempt | 66.88 | Poor | |

| 5. Final actions, anticipating death (e.g., insurance policies, gifts, will) | 86.02 | Good | |

| 6. Active preparation for the attempt | 69.46 | Poor | |

| 7. Suicide note | 81.89 | Good | |

| 8. Communication of intention before the attempt | 67.20 | Poor | |

| 9. Intention of the attempt | 71.78 | Normal | |

| 10. Expectations about the fatal result | 91.96 | Excellent | |

| 11. Knowledge about the lethality of the method | 89.12 | Good | |

| 12. Seriousness of the attempt | 74.84 | Normal | |

| 13. Attitude towards life/death | 64.13 | Poor | |

| 14. Conception of the medical intervention | 86.15 | Good | |

| 15. Degree of premeditation | 67.96 | Poor | |

| Total cut-off point=11 | 87.53 | Good | |

| SSI | 1. Desire to live | 93.76 | Excellent |

| 2. Desire to die | 67.89 | Poor | |

| 3. Reasons for living/dying | 100.00 | Excellent | |

| 4. Desire to actively attempt suicide | 93.76 | Excellent | |

| 5. Passive suicide attempt | 77.42 | Normal | |

| 6. Duration of the suicidal ideation/desire | 63.51 | Poor | |

| 7. Frequency of the suicidal ideation/desire | 65.48 | Poor | |

| 8. Attitude towards the suicidal ideation/desire | 87.53 | Good | |

| 9. Control over the suicidal act: acting-out/desire | 87.53 | Good | |

| 10. Deterrents (“brakes”) against making an active attempt (family, consequences if not completed) | 74.80 | Normal | |

| 11. Reasons for the planned attempt | 84.84 | Good | |

| 12. Method: specificity/planning | 74.62 | Normal | |

| 13. Method: availability/opportunity | 88.73 | Good | |

| 14. Feeling of “capability to perform the attempt” | 84.84 | Good | |

| 15. Expectancy/anticipation of the attempt itself | 87.53 | Good | |

| 16. Real preparation | 64.62 | Poor | |

| 17. Suicide note | 88.73 | Good | |

| 18. Last arrangements to prepare for death (insurance policies, will, donations, etc.) | 87.53 | Good | |

| 19. Deception/Hiding the planned attempt | 69.38 | Poor | |

| 20. Previous suicide attempts | 93.76 | Excellent | |

| 21. Intention of dying related with the last attempt | 91.35 | Excellent | |

| LRS | Lethality of the suicide attempt | 88.39 | Good |

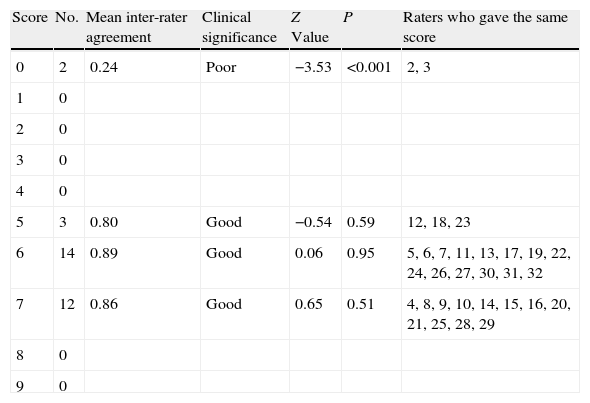

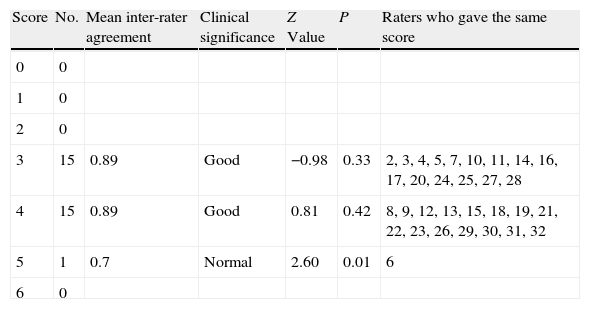

Inter-rater agreement on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale.

| Score | No. | Mean inter-rater agreement | Clinical significance | Z Value | P | Raters who gave the same score |

| 0 | 2 | 0.24 | Poor | −3.53 | <0.001 | 2, 3 |

| 1 | 0 | |||||

| 2 | 0 | |||||

| 3 | 0 | |||||

| 4 | 0 | |||||

| 5 | 3 | 0.80 | Good | −0.54 | 0.59 | 12, 18, 23 |

| 6 | 14 | 0.89 | Good | 0.06 | 0.95 | 5, 6, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 22, 24, 26, 27, 30, 31, 32 |

| 7 | 12 | 0.86 | Good | 0.65 | 0.51 | 4, 8, 9, 10, 14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 25, 28, 29 |

| 8 | 0 | |||||

| 9 | 0 |

The overall mean for inter-rater agreement for each of the items ranged between 75.5% and 100% (Table 1). The agreement level was mainly good to excellent, except for the item “Other psychosocial problems”, in which agreement was weak.

Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) for previous overall activityThe score agreement on this scale was good (82.58%). Only 2 raters (numbers 2 and 3) presented statistically poor agreement (P<.001) compared to the mean of the total scores (reference pattern).

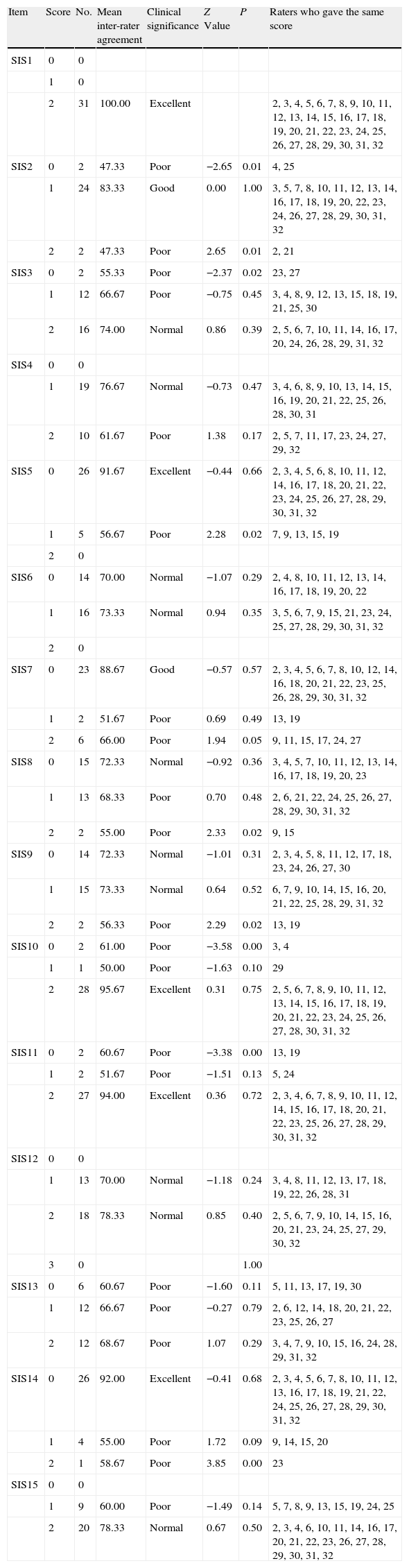

Beck's Suicide Intent Scale Part I: objective circumstances related to the intention of suicideThe overall mean for inter-rater agreement in each of the items ranged from 67.5% to 97% (Table 1). The agreement level for most of the items varied from good to excellent, except for the items 3, 4, 6, 8, 13 and 15 (3. Precautions against discovery/intervention; 4. Actions to obtain help during and after the attempt; 6. Active preparation for the attempt; 8. Communication of intention before the attempt; 13. Attitude towards life/death; and 15. Degree of premeditation), for which significant divergence was detected. The raters whose scores differed most from the others, in each of the items, were raters 5 and 7 (Table 3). Agreement with the total scale score, using a cut-off point of 11, was good (87.5%).

Inter-rater agreement on the items in Beck's Suicide Intent Scale Part I: objective circumstances related to suicide attempt.

| Item | Score | No. | Mean inter-rater agreement | Clinical significance | Z Value | P | Raters who gave the same score |

| SIS1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 1 | 0 | ||||||

| 2 | 31 | 100.00 | Excellent | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |||

| SIS2 | 0 | 2 | 47.33 | Poor | −2.65 | 0.01 | 4, 25 |

| 1 | 24 | 83.33 | Good | 0.00 | 1.00 | 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |

| 2 | 2 | 47.33 | Poor | 2.65 | 0.01 | 2, 21 | |

| SIS3 | 0 | 2 | 55.33 | Poor | −2.37 | 0.02 | 23, 27 |

| 1 | 12 | 66.67 | Poor | −0.75 | 0.45 | 3, 4, 8, 9, 12, 13, 15, 18, 19, 21, 25, 30 | |

| 2 | 16 | 74.00 | Normal | 0.86 | 0.39 | 2, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 14, 16, 17, 20, 24, 26, 28, 29, 31, 32 | |

| SIS4 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 1 | 19 | 76.67 | Normal | −0.73 | 0.47 | 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21, 22, 25, 26, 28, 30, 31 | |

| 2 | 10 | 61.67 | Poor | 1.38 | 0.17 | 2, 5, 7, 11, 17, 23, 24, 27, 29, 32 | |

| SIS5 | 0 | 26 | 91.67 | Excellent | −0.44 | 0.66 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

| 1 | 5 | 56.67 | Poor | 2.28 | 0.02 | 7, 9, 13, 15, 19 | |

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| SIS6 | 0 | 14 | 70.00 | Normal | −1.07 | 0.29 | 2, 4, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22 |

| 1 | 16 | 73.33 | Normal | 0.94 | 0.35 | 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 15, 21, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| SIS7 | 0 | 23 | 88.67 | Good | −0.57 | 0.57 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

| 1 | 2 | 51.67 | Poor | 0.69 | 0.49 | 13, 19 | |

| 2 | 6 | 66.00 | Poor | 1.94 | 0.05 | 9, 11, 15, 17, 24, 27 | |

| SIS8 | 0 | 15 | 72.33 | Normal | −0.92 | 0.36 | 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 23 |

| 1 | 13 | 68.33 | Poor | 0.70 | 0.48 | 2, 6, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |

| 2 | 2 | 55.00 | Poor | 2.33 | 0.02 | 9, 15 | |

| SIS9 | 0 | 14 | 72.33 | Normal | −1.01 | 0.31 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 11, 12, 17, 18, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30 |

| 1 | 15 | 73.33 | Normal | 0.64 | 0.52 | 6, 7, 9, 10, 14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22, 25, 28, 29, 31, 32 | |

| 2 | 2 | 56.33 | Poor | 2.29 | 0.02 | 13, 19 | |

| SIS10 | 0 | 2 | 61.00 | Poor | −3.58 | 0.00 | 3, 4 |

| 1 | 1 | 50.00 | Poor | −1.63 | 0.10 | 29 | |

| 2 | 28 | 95.67 | Excellent | 0.31 | 0.75 | 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 30, 31, 32 | |

| SIS11 | 0 | 2 | 60.67 | Poor | −3.38 | 0.00 | 13, 19 |

| 1 | 2 | 51.67 | Poor | −1.51 | 0.13 | 5, 24 | |

| 2 | 27 | 94.00 | Excellent | 0.36 | 0.72 | 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |

| SIS12 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 1 | 13 | 70.00 | Normal | −1.18 | 0.24 | 3, 4, 8, 11, 12, 13, 17, 18, 19, 22, 26, 28, 31 | |

| 2 | 18 | 78.33 | Normal | 0.85 | 0.40 | 2, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 27, 29, 30, 32 | |

| 3 | 0 | 1.00 | |||||

| SIS13 | 0 | 6 | 60.67 | Poor | −1.60 | 0.11 | 5, 11, 13, 17, 19, 30 |

| 1 | 12 | 66.67 | Poor | −0.27 | 0.79 | 2, 6, 12, 14, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27 | |

| 2 | 12 | 68.67 | Poor | 1.07 | 0.29 | 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, 15, 16, 24, 28, 29, 31, 32 | |

| SIS14 | 0 | 26 | 92.00 | Excellent | −0.41 | 0.68 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

| 1 | 4 | 55.00 | Poor | 1.72 | 0.09 | 9, 14, 15, 20 | |

| 2 | 1 | 58.67 | Poor | 3.85 | 0.00 | 23 | |

| SIS15 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 1 | 9 | 60.00 | Poor | −1.49 | 0.14 | 5, 7, 8, 9, 13, 15, 19, 24, 25 | |

| 2 | 20 | 78.33 | Normal | 0.67 | 0.50 | 2, 3, 4, 6, 10, 11, 14, 16, 17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

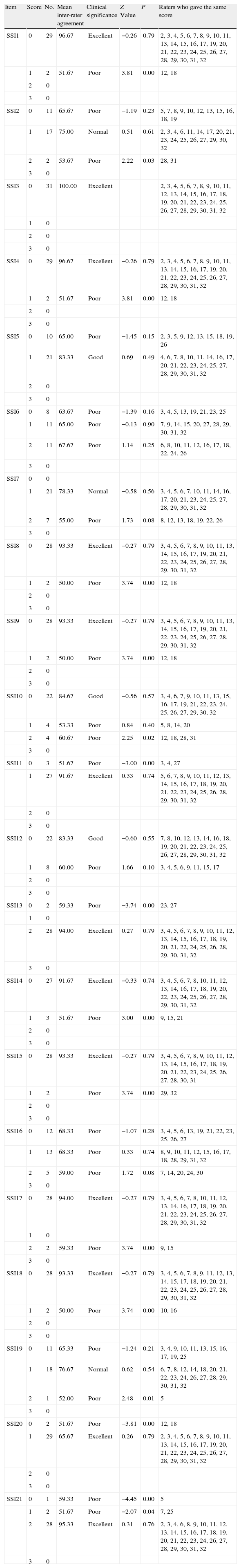

The overall mean for inter-rater agreement in each of the items ranged between 63.51% and 100% (Table 1). The agreement level fell principally between good and excellent, except for the items 2, 6, 7, 16 and 19 (2. Desire to die; 6. Duration of the suicidal ideation/desire; 7. Frequency of the suicidal ideation/desire; 16. Expectation/Anticipation of the actual attempt; and 19. Suicide note), for which there was significant divergence. The raters whose scores differed most from those of the others in each of the items were numbers 12 and 18 (Table 4).

Inter-rater agreement on the Scale for Suicide Ideation items.

| Item | Score | No. | Mean inter-rater agreement | Clinical significance | Z Value | P | Raters who gave the same score |

| SSI1 | 0 | 29 | 96.67 | Excellent | −0.26 | 0.79 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

| 1 | 2 | 51.67 | Poor | 3.81 | 0.00 | 12, 18 | |

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI2 | 0 | 11 | 65.67 | Poor | −1.19 | 0.23 | 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 19 |

| 1 | 17 | 75.00 | Normal | 0.51 | 0.61 | 2, 3, 4, 6, 11, 14, 17, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32 | |

| 2 | 2 | 53.67 | Poor | 2.22 | 0.03 | 28, 31 | |

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI3 | 0 | 31 | 100.00 | Excellent | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | ||

| 1 | 0 | ||||||

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI4 | 0 | 29 | 96.67 | Excellent | −0.26 | 0.79 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

| 1 | 2 | 51.67 | Poor | 3.81 | 0.00 | 12, 18 | |

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI5 | 0 | 10 | 65.00 | Poor | −1.45 | 0.15 | 2, 3, 5, 9, 12, 13, 15, 18, 19, 26 |

| 1 | 21 | 83.33 | Good | 0.69 | 0.49 | 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 14, 16, 17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI6 | 0 | 8 | 63.67 | Poor | −1.39 | 0.16 | 3, 4, 5, 13, 19, 21, 23, 25 |

| 1 | 11 | 65.00 | Poor | −0.13 | 0.90 | 7, 9, 14, 15, 20, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |

| 2 | 11 | 67.67 | Poor | 1.14 | 0.25 | 6, 8, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18, 22, 24, 26 | |

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI7 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 1 | 21 | 78.33 | Normal | −0.58 | 0.56 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 14, 16, 17, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |

| 2 | 7 | 55.00 | Poor | 1.73 | 0.08 | 8, 12, 13, 18, 19, 22, 26 | |

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI8 | 0 | 28 | 93.33 | Excellent | −0.27 | 0.79 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

| 1 | 2 | 50.00 | Poor | 3.74 | 0.00 | 12, 18 | |

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI9 | 0 | 28 | 93.33 | Excellent | −0.27 | 0.79 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

| 1 | 2 | 50.00 | Poor | 3.74 | 0.00 | 12, 18 | |

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI10 | 0 | 22 | 84.67 | Good | −0.56 | 0.57 | 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13, 15, 16, 17, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32 |

| 1 | 4 | 53.33 | Poor | 0.84 | 0.40 | 5, 8, 14, 20 | |

| 2 | 4 | 60.67 | Poor | 2.25 | 0.02 | 12, 18, 28, 31 | |

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI11 | 0 | 3 | 51.67 | Poor | −3.00 | 0.00 | 3, 4, 27 |

| 1 | 27 | 91.67 | Excellent | 0.33 | 0.74 | 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI12 | 0 | 22 | 83.33 | Good | −0.60 | 0.55 | 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

| 1 | 8 | 60.00 | Poor | 1.66 | 0.10 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 11, 15, 17 | |

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI13 | 0 | 2 | 59.33 | Poor | −3.74 | 0.00 | 23, 27 |

| 1 | 0 | ||||||

| 2 | 28 | 94.00 | Excellent | 0.27 | 0.79 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI14 | 0 | 27 | 91.67 | Excellent | −0.33 | 0.74 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

| 1 | 3 | 51.67 | Poor | 3.00 | 0.00 | 9, 15, 21 | |

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI15 | 0 | 28 | 93.33 | Excellent | −0.27 | 0.79 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 30, 31 |

| 1 | 2 | Poor | 3.74 | 0.00 | 29, 32 | ||

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI16 | 0 | 12 | 68.33 | Poor | −1.07 | 0.28 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 13, 19, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27 |

| 1 | 13 | 68.33 | Poor | 0.33 | 0.74 | 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 28, 29, 31, 32 | |

| 2 | 5 | 59.00 | Poor | 1.72 | 0.08 | 7, 14, 20, 24, 30 | |

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI17 | 0 | 28 | 94.00 | Excellent | −0.27 | 0.79 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

| 1 | 0 | ||||||

| 2 | 2 | 59.33 | Poor | 3.74 | 0.00 | 9, 15 | |

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI18 | 0 | 28 | 93.33 | Excellent | −0.27 | 0.79 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

| 1 | 2 | 50.00 | Poor | 3.74 | 0.00 | 10, 16 | |

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI19 | 0 | 11 | 65.33 | Poor | −1.24 | 0.21 | 3, 4, 9, 10, 11, 13, 15, 16, 17, 19, 25 |

| 1 | 18 | 76.67 | Normal | 0.62 | 0.54 | 6, 7, 8, 12, 14, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |

| 2 | 1 | 52.00 | Poor | 2.48 | 0.01 | 5 | |

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI20 | 0 | 2 | 51.67 | Poor | −3.81 | 0.00 | 12, 18 |

| 1 | 29 | 65.67 | Excellent | 0.26 | 0.79 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | ||||||

| SSI21 | 0 | 1 | 59.33 | Poor | −4.45 | 0.00 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 51.67 | Poor | −2.07 | 0.04 | 7, 25 | |

| 2 | 28 | 95.33 | Excellent | 0.31 | 0.76 | 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |

| 3 | 0 |

The agreement reached in the score for this scale was good (88.39%). There was only a single rater (number 6) who presented an average level of agreement with the mean for the total scores (standard pattern) (Table 5).

Inter-rater agreement on the Lethality Rating Scale (LRS) for suicide attempts.

| Score | No. | Mean inter-rater agreement | Clinical significance | Z Value | P | Raters who gave the same score |

| 0 | 0 | |||||

| 1 | 0 | |||||

| 2 | 0 | |||||

| 3 | 15 | 0.89 | Good | −0.98 | 0.33 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, 11, 14, 16, 17, 20, 24, 25, 27, 28 |

| 4 | 15 | 0.89 | Good | 0.81 | 0.42 | 8, 9, 12, 13, 15, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 26, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

| 5 | 1 | 0.7 | Normal | 2.60 | 0.01 | 6 |

| 6 | 0 |

The objective of this study was to evaluate the reliability of a questionnaire for assessing suicidal behaviour (Brief Suicide Questionnaire) for its research use in a multi-centre project using the assessments of multiple raters on a sample from a single patient. Our study results make it possible to state that the clinical scales that compose this questionnaire have reliability. What is more, the reliability observed is attributable to specific raters and, in the case of the scales with more than 1 item, it is related to the fact that some raters left some of the item answers blank.

It should not be forgotten that, as this is a design with only 1 patient, it may not be possible to generalise the results on tool reliability to the population from which the patient was selected. Faced with constructing a tool applicable to clinical situations, the approach to estimating its reliability would be different. That would require assessing various videotaped patients (approximately 10 for each observer included) and using other statistical parameters like the weighted Kappa or the interclass coefficient of correlation or quantitative or ordinal scales. Our study might let developers of such a project know where the areas of low consistency of these tools are and which areas could initially be eliminated in consequence.

The sole-case design controls the sources of variability related to the exam and to patient assessment; in this way, assessment variability is reduced to the factors depending on the rater. In fact, as has been indicated earlier, identifying raters whose assessments differed most from the group was one of our study objectives. In the preparation stage of all types of multi-centre studies (including clinical trials), using this kind of design (agreement of multiple assessors on a single patient) has proved useful for detecting areas of low consistency and identifying assessors who differ from the group.17 Nevertheless, it is important to note that this design type is rare in the literature, principally due to the complexity of the statistical treatment that it involves.16 Solving this problem with the procedures proposed by Cicchetti and Showalter,16 the procedure that we describe here can make the preparation stage more efficient for multi-centre study researchers. One of the most important characteristics of this preparation is training the examiners until appropriate inter-rater reliability can be guaranteed. Identifying items and raters with low levels of reliability, followed by specific training in the most conflictive items, could help to correct potential sources of variability in assessing the participants in a clinical trial. This would, in turn, contribute to increasing design strength without having to enlarge study sample size.17

In summary, as the results of this study manifest, the technique developed by Cicchetti et al.16 helps to meet these objectives efficiently, because it requires a very small sample size (1 subject), a single assessment session that can be pre-recorded, and it does not require all of the researchers to assess the subject at the same time, given that the indexes can be calculated later on. In addition, the new technologies (like videoconferences) allow the assessments to take place at the same time but from different places. With respect to the Brief Suicide Questionnaire, we can conclude that it presents appropriate inter-rater agreement for research purposes while identifying the areas of low agreement and the raters who distance themselves from the overall agreement. To use this tool with greater reliability, measures for investigator training have been implemented.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: Concepción Vaquero Lorenzo.

Corporación Sanitaria Universitaria Parc Taulí de Sabadell, Barcelona: Gemma García-Parés, María Giró Batalla, M. Garrido.

Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, CIBERSAM: M. Aragues.

Hospital Carlos Haya and Fundación IMABIS, Málaga: E. Martín, M. Alba, M.I. Gómez, A. González, M. Maté, M. Romero and N. Cantero.

Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona, CIBERSAM: J. Hernández and S. Durán Sindreu.

Universidad de Oviedo, CIBERSAM: Maria Teresa Bascarán, Julio Bobes, Manuel Bousoño and P. Burón, Luis Jiménez Treviño.

The group members are listed in Appendix A.

Please cite this article as: García-Nieto R, et al. Protocolo breve de evaluación del suicidio: fiabilidad interexaminadores. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2012;5:24–36.