The present study aimed to obtain a short form of the Spanish version of the WAIS-IV for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia that requires about half an hour to be administered. The reduced test can be very useful in clinical and research settings when an estimation of the intelligence quotient (IQ) is required to decide about intervention programs or to describe the sample.

Materials and methodsA sample of 143 patients participated in the study, 91 out of them were the test group, and the other 52 were used for a cross-validation analysis. To increase the content validity, the decision was made to create a short form composed of a subtest of each of the four cognitive domains that the scale measures.

ResultsSeveral analyses showed that the best combination was composed of the Information, Block Design, Arithmetic, and Symbol Search subtests. Nine different criteria were calculated to evaluate the quality of the short form.

ConclusionsThe data showed very good results for the criteria: correlations, difference of means, and cross-validation. The results were satisfactory for: category agreement, band of error, clinical accuracy, and reliability.

El objetivo de este estudio ha sido obtener una forma corta de la versión española de la WAIS-IV para pacientes con diagnóstico de esquizofrenia que necesite entorno a media hora para ser administrada. Una forma abreviada puede ser muy útil en contextos clínicos y de investigación cuando se necesite una estimación del cociente intelectual (CI) de pacientes con diagnóstico de esquizofrenia para su adscripción a programas de intervención o para la descripción de la muestra.

Materiales y métodosParticipó en el estudio una muestra de 143 pacientes. 91 formaron el grupo de test, y los otros 52 se utilizaron en un análisis de validación cruzada. Para aumentar la validez de contenido, se tomó la decisión de crear una forma corta compuesta por un subtest de cada uno de los cuatro dominios cognitivos que mide la escala.

ResultadosVarios análisis mostraron que la mejor combinación era la compuesta por los subtests: Información, Cubos, Aritmética y Búsqueda de Símbolos. Se calcularon nueve criterios diferentes para evaluar la calidad de esta forma corta.

ConclusionesLos datos mostraron muy buenos resultados en los criterios basados en las correlaciones, las diferencias de medias y la validación cruzada, y resultados satisfactorios en los criterios de acuerdos en la categoría, margen de error, precisión clínica y fiabilidad.

The following are the tests routinely used for cognitive assessment in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia: MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB),1 Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS),2 Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS)3,4 and Spanish version of the Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry (SCIP-S).5 These tests are developed to assess cognitive deficits in specific areas, but do not provide a measure of intelligence quotient (IQ). However, publications such as the Report from the Working Group Conference on Multisite Trial Design for Cognitive Remediation in Schizophrenia6 state that IQ should be considered among the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the design of cognitive rehabilitation interventions. It is recommended that participants should score above 75−80. Therefore, a test such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) should be used to assess IQ, and given the length of the test, an abbreviated form is the option to use in these trials.7

The WAIS is the most widely used test for assessing intellectual performance in both clinical and non-clinical contexts.8–10 The WAIS has been revised several times to improve it and keep its contents up to date. The latest version, the WAIS-IV, appeared 10 years ago,11 but the Spanish version is more recent.12 The scale provides 2 general scores that summarise global intellectual abilities, the Full Scale IQ test (FSIQ) and the General Ability Index. The FSIQ is obtained from combining total scores or indices in 4 cognitive areas: Verbal Comprehension (VCI), Perceptual Reasoning (PRI), Working Memory (WMI), and Processing Speed (PSI), while the General Ability Index provides an estimate with less emphasis on the WMI and PSI. The scale comprises 10 main subtests and 5 optional subtests. Only 3 of these subtests are new, the remaining 12 are from the WAIS-III.13 The 10 main subtests need to be applied to obtain the FSIQ: Similarities (SI), Vocabulary (VO), and Information (IN) are the VCI subtests; Block Design (BD), Matrix Reasoning (MR), and Visual Puzzles (VP) are the PRI subtests; Digit Span (DS) and Arithmetic (AR) are the WMI subtests; and Symbol Search (SS) and Digit Symbol Coding (CD) are the PSI subtests. The optional subtests should be used when there are problems in administering the main subtests, or when the assessor wants to explore a cognitive function in more depth. The time required to administer the test can sometimes be a problem as it ranges from 60 to 90 min.11 It can take considerably longer when used in clinical populations, such as patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.14 However, assessing cognitive functioning is very important to design optimal psychosocial rehabilitation programmes for these patients. A short form (SF) of this scale could be useful, therefore, if the assessor has insufficient time or when preliminary screening of the patient is required.15,16 This is why several SFs of the test have been developed from the first to the current version.

There are two methods to reduce the full scale. The first is to reduce the number of subtests, leaving the selected subtests intact. The second is to reduce the number of items in each subtest, which leaves the scale structure intact. According to research comparing these 2 reduction methods,17–19 the validity indices are similar, but reducing the subtests gives higher reliability scores than reducing the items, and some authors suggest that subtest reduction gives a more accurate estimation of the FSIQ.20 However, the administration of some subtests allows the remaining subtests to be used if a complete cognitive assessment is required. Moreover, a research study21 that analysed a proposed item reduction22 for the Spanish version of the WAIS-III comparing different populations concluded that item reduction was good for some groups, but not for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia.

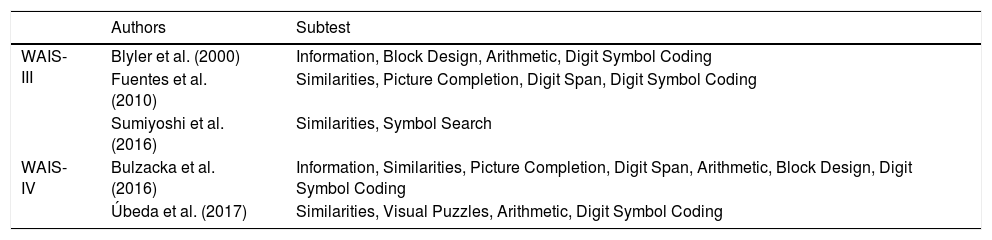

Several SFs of the WAIS have been constructed for different populations,15,23–27 including patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Research28 with the WAIS-R on these types of patients has demonstrated the quality of the Kaufman short form29 that comprises the 4 subtests: SI, AR, Picture Completion (PC) and CD. Other research30 comparing Kaufman’s proposal29 of 4 subtests with a different,31 7-subtest version concluded that the 4-subtest version is better when estimating FSIQ, but that the 7-subtest version31 had the lowest misclassification rate. Some later studies32–34 also focussing on the 7-subtest proposal31,35 have demonstrated the quality of this SF. Another study36 has shown that an SF including the VO and BD subtests is optimal for patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. For the WAIS-III, a benchmark research study1 in this field decided to choose one subtest from each of the cognitive domains, and showed that the best combination of 4 subtests was: IN, BD, AR, and CD. However, other authors,37 following this criterion, have proposed an SF made up of subtests SI, PC, DS and CD. There have also been mixed versions38 that included the CD subtest and part of the items from the BD, IN and AR subtests. Another study39 later showed that the dyad formed by the SI and SS subtests of the WAIS-III was useful for estimating IQ in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Construction of an SF of the WAIS-IV has also been attempted for patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The results of a recent research study40 that examined the psychometric properties of 4 different versions of the SF31 of 7 subtests showed good estimates of IQ, but low clinical accuracy rates for cognitive factors. For the Spanish version of the WAIS-IV, a preliminary exploratory study41 based on a sample of 35 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia showed that the SI, VP, AR, and CD subtests provided good estimates of FSIQ. The data showed a high correlation between estimated and actual IQ (.94), non-significant mean differences and 71% classification accuracy according to the WAIS categories. The results should be viewed with caution due to the small sample size. Table 1 shows the SFs based on subtest reduction obtained from applying the WAIS-III and WAIS-IV in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. We have not included earlier versions because they do not have the same 4-index structure.

Summary of the short forms of the WAIS-III and WAIS-IV developed for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia.

| Authors | Subtest | |

|---|---|---|

| WAIS-III | Blyler et al. (2000) | Information, Block Design, Arithmetic, Digit Symbol Coding |

| Fuentes et al. (2010) | Similarities, Picture Completion, Digit Span, Digit Symbol Coding | |

| Sumiyoshi et al. (2016) | Similarities, Symbol Search | |

| WAIS-IV | Bulzacka et al. (2016) | Information, Similarities, Picture Completion, Digit Span, Arithmetic, Block Design, Digit Symbol Coding |

| Úbeda et al. (2017) | Similarities, Visual Puzzles, Arithmetic, Digit Symbol Coding |

The aim of this study was to obtain an abbreviated version of the WAIS-IV for use in the population diagnosed with schizophrenia. There has been a previous proposal40 for an SF, but it seems too long because the full scale is only shortened by 30%. Our goal is an SF that can be administered in 30 min or less. For the SF to maintain the structure of the full scale and provide information in all 4 cognitive areas, we will look for an SF that contains 4 of the main subtests, one from each of the cognitive domains assessed. This criterion has been used by several authors,8,38 and is a way of obtaining content validity.42 The definition of the construct could be affected if any domain is omitted.

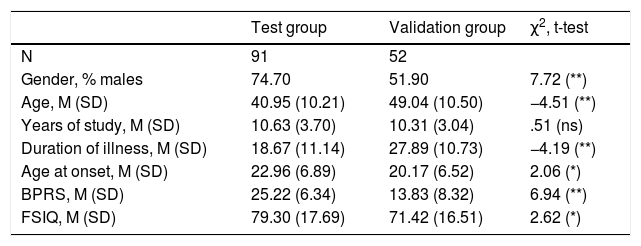

Materials and methodsPatientsA total of 143 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were included in the study. They were inpatients and outpatients from the Psychosocial Rehabilitation Centres of Sueca and Segorbe, the Malvarrosa Mental Health Unit, the Miguel Servet Day Hospital, and the State Psychosocial Care Referral Centre for people with mental illness, all of which are in the Valencian Community. The patients met the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia. Diagnoses were confirmed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID).43 Inclusion criteria were aged 18–65 years, no substance or alcohol dependence, neurological disorders, or a perceptual impairment that made it difficult to understand the WAIS-IV instructions. All the participants were clinically stable, with no exacerbation of symptoms for at least 3 months prior to assessment. They attended the centre regularly and adhered to pharmacological treatment with antipsychotics. They provided their informed consent to participate in the study. The research was approved by the ethics committees of the centres participating in the study, and followed the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients from the latter 3 centres (n = 91) formed the test group, and the remaining 3 (n = 52) were used as the validation group. Table 2 lists the main sociodemographic, clinical, and cognitive characteristics of the patients.

Sociodemographic, clinical, and cognitive variables of the test group and crossed validation group.

| Test group | Validation group | χ2, t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 91 | 52 | |

| Gender, % males | 74.70 | 51.90 | 7.72 (**) |

| Age, M (SD) | 40.95 (10.21) | 49.04 (10.50) | −4.51 (**) |

| Years of study, M (SD) | 10.63 (3.70) | 10.31 (3.04) | .51 (ns) |

| Duration of illness, M (SD) | 18.67 (11.14) | 27.89 (10.73) | −4.19 (**) |

| Age at onset, M (SD) | 22.96 (6.89) | 20.17 (6.52) | 2.06 (*) |

| BPRS, M (SD) | 25.22 (6.34) | 13.83 (8.32) | 6.94 (**) |

| FSIQ, M (SD) | 79.30 (17.69) | 71.42 (16.51) | 2.62 (*) |

ns: not significant.

BPRS: Brief psychiatric rating scale; FSIQ: full scale intellectual quotient.

We will follow a procedure like that used by Ringe et al.44 to ensure that the SF can be generalised to the maximum. These authors compared the quality of 4 dyadic forms of the WAIS-III in part of a sample of patients (75% of the sample) with psychiatric or neurological disorders. They then performed the same calculations on the remaining 25% of the sample to verify that the results were similar. In their study, both samples were randomly selected from the full group. We will use a different cross-validation criterion in our research study. Our purpose is to study whether the SF works well in schizophrenic patients with different cognitive impairment profiles, and we will use two groups. The first (test group, TG) with a typical profile (standard deviation below normal controls), and the second (validation group, VG) with more severe cognitive impairment. Thus, the SF could be used in different clinical contexts. As can be seen in Table 2, the two groups differed in all demographic and clinical characteristics analysed except for years of study. As they are not equivalent samples, the validation is easier to generalise.

Each patient was assessed individually by a clinical psychologist over 2 sessions. In the first session, each participant was informed about the study, and relevant demographic and clinical data were collected along with their informed consent. Symptoms were assessed using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).45 In the second session, each participant completed the 10 core tests of the WAIS-IV according to the standard procedure described in the manual,12 under appropriate acoustic and visual conditions.

Data analysisIBM SPSS Statistics version 20 was used for the analyses. Each patient’s FSIQ was calculated following the scoring guidelines of the WAIS-IV technical manual12: the direct scores of the 10 tests were converted into scalar scores, totalled and the final FSIQ was obtained using the manual's conversion table. Then the normality of the FSIQ distribution in the sample was checked. The same procedure was used to calculate the 4 indices. The first calculations, performed only on the test group data, were to obtain the subtest that best represented each index. Two types of analyses were performed: a) sum of the scalar scores for each cognitive domain, and b) stepwise regression to explain VCI, PRI, WMI and PSI using the subtests of each index as factors. With the selected subtests, 2 estimates of the FSIQ were made using 2 prorating methods for the scores. The last step was to determine the quality of both estimates by calculating indicators following the procedure proposed by Bulzacka et al.,40 who used 9 different criteria selected from key studies in this field:24,33,46,47

- 1)

Spearman correlation coefficients: based on some previous studies,32 it was assumed that correlations over .90, are sufficiently high, given that the 2 correlated scores (obtained FSIQ and estimated FSIQ) were from the same administration of the full scale and, therefore, the correlation may be over-dimensioned

- 2)

Comparison of means: by calculating t-tests for dependent samples, and calculating effect size using Cohen's d indicating the clinical significance of the difference

- 3)

Difference in mean scores (complete version-short version): to eliminate systematic over- or underestimations.

- 4)

Category agreement analysis: the patients’ FSIQ is classified into 7 categories following the criteria of the WAIS-IV12 manual: Very low (up to 69), Borderline (70–79), Low Normal (80–89), Medium (90–109), High Normal (110–119), Superior (120–129) and Very Superior (130 or more). In addition, the classification is also made with the estimated FSIQ and the agreement rate between the two classifications is calculated. According to Bulzacka et al.,40 an agreement of more than 80% is considered acceptable.

- 5)

Error margin analysis: to detect relevant estimation errors, an error margin of 2 standard errors of measurement (SEM) was established around the FSIQ. According to the technical manual (Spanish edition, p. 46), the mean SEM is 3.45 points. The percentage of cases within this range is calculated, and 80% is again set as the minimum acceptable threshold.

- 6)

Clinical accuracy: percentage of cases achieving at least one of the 2 previous criteria, i.e., category agreement and/or error margin.

- 7)

Time saving: since different ways are compared of estimating the FSIQ, not different versions, this criterion is only descriptive. The calculations indicate the reduced time of the SF compared to the full scale. Calculation is based on the time measurements used for the WAIS-III subtests14,48 because, to our knowledge, no studies have been conducted with the WAIS-IV.

- 8)

Reliability (internal consistency): the minimum desirable is .90.46

- 9)

Criterion validity: Some authors40 calculate this index using a measure of functional outcome, the Social Autonomy Scale, and duration of illness as external criteria. In their findings, neither the actual FSIQ nor their estimates were related to functional outcome or duration of illness. As we sought a different measure of validity in this study, we changed the procedure for assessing validity: cross-validation of the SF with a different sample, the VG. Recent articles uphold the importance of the cross-validation approach as a replicability mechanism in psychology.49 The other 8 criteria were also calculated for this second sample.

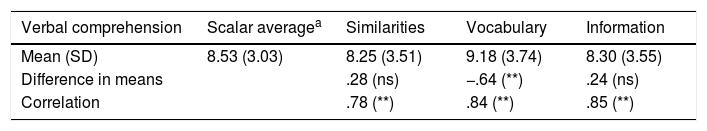

To select the subtests that best represent each index, the sum of the scalar scores for each index was divided by the number of subtests making up the index (2 or 3) to obtain the scalar average. The differences between the means in the scales and the scalar average were calculated and correlations were calculated (Table 3).

Comparison of each subtest with the scalar average of each cognitive domain.

| Verbal comprehension | Scalar averagea | Similarities | Vocabulary | Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 8.53 (3.03) | 8.25 (3.51) | 9.18 (3.74) | 8.30 (3.55) |

| Difference in means | .28 (ns) | −.64 (**) | .24 (ns) | |

| Correlation | .78 (**) | .84 (**) | .85 (**) |

| Perceptual reasoning | Scalar average | Block Design | Matrices | Visual Puzzles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 7.19(2.81) | 7.53 (3.11) | 6.47 (3.20) | 7.56 (3.50) |

| Difference in means | −.33 (ns) | .72 (**) | −.37 (ns) | |

| Correlation | .87 (**) | .86 (**) | .85 (**) |

| Working memory | Scalar average | Digit symbols | Arithmetic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 7.10 (2.55) | 6.87 (2.83) | 7.34 (3.02) |

| Difference in means | .24 (ns) | −.24 (ns) | |

| Correlation | .86 (**) | .88 (**) |

| Processing speed | Scalar average | Symbol Search | Digit Symbol Coding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (DT) | 5.79 | 6.14 (2.96) | 5.44 (2.78) |

| Difference in means | (2.69) | −.35 (*) | .35 (*) |

| Correlation | .94 (**) | .93 (**) |

ns: not significant.

The most appropriate subtest to represent each cognitive domain will show the smallest difference between means and the highest correlation with the scalar average. The subtests IN, BD, AR and SS best met these criteria. To ensure that these subtests were the most appropriate and that they were good estimates of the indices, several stepwise linear regressions were calculated to estimate the 4 indices, using the subtests as factors. In the regression to predict the VCI, the analysis showed that the first model had a single predictive factor, IN scores, explaining 72.3% of the variance. When the PRI, was estimated, the best model had the BD subtest as the only factor, explaining 75.6% of the variance. In the case of WMI, the most predictive subtest was AR, explaining 77.5% of the variance. Finally, for PSI, the best subtest was SS, explaining 88.7% of the variance. The 2 types of analysis resulted in the selection of the same subtests.

Bulzacka et al.40 compared 4 FSIQ estimates based on the combination of 2 forms31,50 of 7 subtests and 2 estimation methods: a) prorated scores and b) linear regression scores. With the prorating method, the formula ((IN + SI + BD + PC + DS + AR + CD)/7) × 10 is calculated to obtain an estimate of the mean scalar score (sum of the 10 subtests), which is then converted into the FSIQ according to the conversion tables in the manual. The regression-based method directly estimates the FSIQ from the scalar scores of the 7 subtests using a linear regression equation. The authors of this paper recommend using the prorating method due to its better psychometric properties. In addition, the regression coefficients vary for different samples.8 It is also important to bear in mind that practitioners demand simplicity. Calculation of the prorating method is simpler than the calculation of a regression equation and allows practitioners to follow the usual process to obtain the FSIQ as indicated in the technical manual,12 except that the sum of the scalar scores is not achieved by including 10 scores, but by prorating the scores of 4 subtests. Based on all this information, we decided to use the prorating method to obtain the estimated FSQT. There are 2 possible prorating procedures: weighting or unweighting the scores of the subtests. In the first method, with weighting (PRO1), each scalar score is multiplied by 3 or by 2, depending on the index in question (3 × IN + 3 × BD + 2 × AR + 2 × SS). In the second method, without weighting (PRO2),8,40 all scalar scores have the same weight in the calculation of the final score. For a 4-subtest SF, the formula is ((IN + BD + AR + SS)/4) × 10, i.e., (IN + BD + AR + SS) × 2.5. The first option better represents the internal structure of the test, but the second requires a simpler calculation. The 2 FSIQ estimates will be compared to assess which is better.

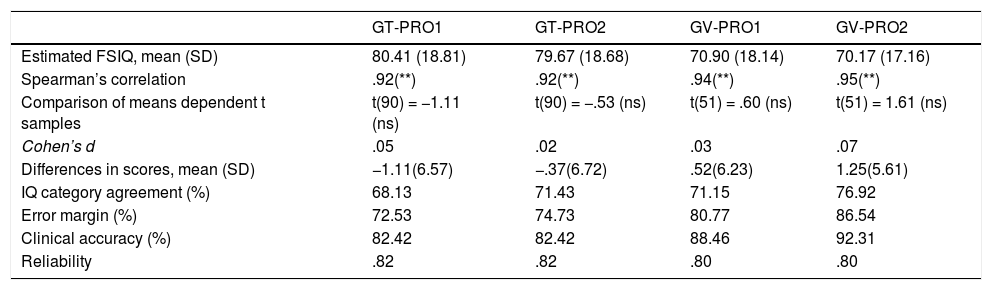

Table 4 shows the criteria40 that were calculated. When the analyses in the TG were looked at, some of the required thresholds were met, but not all. The correlation coefficients between the actual and estimated FSIQ are good for the 2 prorating methods. The comparison of means is not statistically significant in any of the 2 methods, but the smallest difference is for PRO2, as shown in the mean differences between scores. Neither the category agreements nor the error margin reached the desired 80%, but PRO2 obtained higher percentages in both indicators. Clinical accuracy and Spearman-Brown reliability are acceptable, with similar values for the 2 pro-rating methods. The calculations with the VG data showed excellent results, with better indices than in the TG. Of note are the good results of PRO2, with percentages of agreement in the IQ categories above 75%, error margin above 85% and clinical accuracy above 90%. Therefore, we can conclude that the cross-validation was satisfactory. Furthermore, according to different estimates14,48 the time saved is between 53% and 59%.

Comparison of the FSIQ of the 2 SFs (PRO1 and PRO2) and that of the full scale in the 2 groups of patients: test group (TG; N = 91) and cross-validation group (VG; N = 52).

| GT-PRO1 | GT-PRO2 | GV-PRO1 | GV-PRO2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated FSIQ, mean (SD) | 80.41 (18.81) | 79.67 (18.68) | 70.90 (18.14) | 70.17 (17.16) |

| Spearman’s correlation | .92(**) | .92(**) | .94(**) | .95(**) |

| Comparison of means dependent t samples | t(90) = −1.11 (ns) | t(90) = −.53 (ns) | t(51) = .60 (ns) | t(51) = 1.61 (ns) |

| Cohen’s d | .05 | .02 | .03 | .07 |

| Differences in scores, mean (SD) | −1.11(6.57) | −.37(6.72) | .52(6.23) | 1.25(5.61) |

| IQ category agreement (%) | 68.13 | 71.43 | 71.15 | 76.92 |

| Error margin (%) | 72.53 | 74.73 | 80.77 | 86.54 |

| Clinical accuracy (%) | 82.42 | 82.42 | 88.46 | 92.31 |

| Reliability | .82 | .82 | .80 | .80 |

ns: not significant.

The usefulness of short versions of the WAIS for a general estimation of cognitive functioning in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia has been extensively demonstrated. However, only 2 studies have been published on the SF of the WAIS-IV for this population. One,41 like our study, uses a subtest of each cognitive domain (SI, VP, AR, DS); however, it is a pilot study based on a small sample of 35 patients, and the results are merely exploratory. The other study40 is a relevant reference in this field. It is based on a sample of 70 patients (49 with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and 21 with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder). The authors studied the quality of 2 of the SFs of 7 Ward subtests using 2 different methods to estimate FSIQ: prorating vs. regression. The conclusion was that all 4 SFs compared provide good estimates of FSIQ, the prorated forms providing better predictions. The present paper uses that study as a basic reference for planning the calculations; therefore, the 9 indices that they calculated were studied in this work. The only exception was the validity indicator, because in their study they found no relationship between some measures of global functioning (clinical remission and duration of illness) and both estimated and actual FSIQ, and therefore we decided to use a different method to obtain validity. We conducted a cross-validation study with a non-random sample of more cognitively impaired patients from psychosocial rehabilitation centres. The aim was to test whether the SF we proposed is useful in patients with different degrees of cognitive impairment. The values shown in Table 3 mean we can conclude that the 4-subtest SF studied is a good tool for estimating FSIQ as most of the indicators meet the minimum desired criteria. Those of category agreement and error margin do not achieve the desired percentages, but these results are consistent with those of other research studies8,44 that show percentages ranging from 46% to 67%. In addition, as highlighted by some authors,35 SFs should not be used to categorise for the purpose of diagnosis. Reliability is slightly lower than in the study by Bulzacka et al.,40 but we must bear in mind that they used 7 subtests, and reliability is related with the length of the scales.

The present SF shares 3 of the 4 subtests of the SF of Blyler et al.,8 as the CD subtest is replaced by the SS subtest. In the initial regression conducted to obtain the subscale with the highest predictive power over the PSI, the variance explained by SS was slightly higher than the variance explained by CD.

To decide the best prorating option, we must consider a recent research study51 that shows a high percentage of administrative, scoring and recording errors when the Wechsler test was administered by psychologists or graduate students; simplicity, therefore, is a factor to be considered. Considering that PRO2 is simpler than PRO1, and that the indicators are slightly better, we believe that the second prorating method is the better choice. The last point for the final decision is the study of the results in the validation sample. Table 3 shows that the quality indicators are adequate in both methods, highlighting the significant increase observed in category agreement, error margin, and clinical accuracy in PRO2. Therefore, the validation sample confirms the suitability of this method. It would be very interesting to conduct further research focusing on the relationship between daily functioning and cognitive functioning in chronic patients,52,53 as well as in first episodes,54 as in previous studies39 conducted with the WAIS-III.

ConclusionsIn all, for our proposed reduced-form WAIS-IV, the second prorating method and the 4 subtests studied showed very good results for some indicators, such as correlations, mean difference, and cross-validation, and moderate results for category agreement, error margin, clinical accuracy, and reliability. The percentage of time saved is adequate, and we achieved the aim of achieving an SF that can be administered in less than half an hour. For each patient, the procedure that the practitioner should follow is: (a) obtain the direct scores on the 4 subtests, (b) convert the direct scores into scalar scores for the corresponding age (administration and scoring manual), (c) estimate the sum of the subtests in the full scale with this calculation ((IN + BD + AR + SS) × 2.5), and (d) look up the FSIQ estimate in the corresponding table in the manual. Caution is needed when using the SF for clinical screening due to its moderate level of accuracy in classifying into categories. The estimated time for administration of the WAIS-IV subtests, indices and SF will help the practitioner to decide whether to use the full test or a SF. The 7-subtest FC of Bulzaka et al.40 is an option, but it is a "long" SF, and therefore the current proposed SF with 4 subtests may be a suitable option when time is more limited.

FundingThis study was funded by the Dirección General de Universidades, Investigación y Ciencia del Gobierno de la Comunidad Valenciana, Spain [project number: GV/AICO/2016/070].

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors would like to thank the users and staff of the Sueca and Segorbe Rehabilitation and Social Integration Centres, the Malvarrosa Mental Health Unit, the Miguel Servet Day Hospital, and the State Reference Centre for Psychosocial Care in Valencia.

Please cite this article as: Dasí C, Fuentes-Durá I, Ruiz JC, Navarro M. Forma corta de cuatro subtest de la WAIS-IV para la evaluación de pacientes con diagnóstico de esquizofrenia. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2021;14:139–147.