The main aims of our study were to estimate the current rates and pattern of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) use in Spain, as well as exploring the causes that may be limiting its use in our country.

MethodsA cross-sectional survey was conducted covering every psychiatric unit in Spain as of 31 December 2012.

ResultsMore than half (54.9%) of the psychiatric units applied ECT at a rate of 0.66 patients per 10,000 inhabitants. There are wide variations with regard to ECT application rates between the different autonomous communities (0.00–1.39) and provinces (0.00–3.90). ECT was prescribed to a mean of 25.5 patients per hospital that used the technique and 4.5 in referral centre (P=.000), but wide differences were reported in the number of patients who were prescribed ECT from hospital to hospital.

ConclusionsAlthough the percentage of psychiatric units applying ECT in our country is among the highest in the world, the ECT application rate in Spain is among the lowest within western countries. Large differences in ECT use have been reported across the various autonomous communities, provinces and hospitals. Thus, health planning strategies need to be implemented, as well as promoting training in ECT among health professionals, if these differences in ECT use are to be reduced.

Analizar en términos cuantitativos y cualitativos la situación del uso de la terapia electroconvulsiva (TEC) en España en la actualidad, así como explorar aquellos aspectos que pudieran condicionar su utilización.

MetodologíaEncuesta transversal en todas las unidades psiquiátricas existentes en España a fecha 31/12/2012.

ResultadosEl 54,9% de las unidades estudiadas aplicaban TEC, resultando en una tasa de aplicación de 0,66 por 10.000 habitantes. Existen amplias variaciones en las tasas de aplicación entre comunidades autónomas (0,00-1,39) y provincias (0,00-3,90). La TEC se indicó en el período estudiado a una media de 25,5 pacientes en los centros que disponían de la técnica, y a 4,5 en los centros que remitían a otros para aplicarla (p=0,000), pero con amplias diferencias entre centros.

ConclusionesEl número de centros que disponen de TEC en España es uno de los más elevados entre los países occidentales, pero la tasa de aplicación de esta técnica continúa siendo una de las más bajas, existiendo además marcadas diferencias entre las distintas comunidades autónomas, e incluso entre provincias y centros hospitalarios de una misma comunidad autónoma. Parece preciso implementar estrategias de planificación sanitaria y de formación para reducir la heterogeneidad observada en la prescripción y aplicación de la TEC en España.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is one of the psychiatric treatments with the highest rates of efficacy and safety in the treatment of some severe mental disorders. In spite of this, there is a high degree of variability in usage of this technique. Worldwide the rate of use varies from 0.04 patients per 10,000 inhabitants-year in Latvia to 5.10 in the United States, with an average of 2.34 patients per 10,000 inhabitants-year.1 In Europe usage rates stand at more than 3 patients per 10,000 inhabitants-year in Belgium,2,3 the United Kingdom4,5 or the Scandinavian countries,6,7 although the rate is lower than 0.5 in Germany8 and many East European countries.9–12 Moreover, the use of ECT is prohibited in Slovenia and it is practically extinct in Italy.13

Variations in the use of ECT are not restricted to geographically distant countries with very different social and healthcare situations. Thus for example, in the United States Hermann et al.14 warned of the existence of enormous differences between different healthcare regions, as rates of ECT usage vary from 0.4 to 81.2 patients per 10,000 inhabitants-year, while in Europe wide variations have been reported, not only between neighbouring countries15,16 but also between different regions in the same country, as is the case in England,5 Norway17 or Belgium.2 Glen and Scott18 have reported variations of almost 20 times in the rates of ECT use among the different psychiatric teams in a single hospital in Edinburgh. Data on how its use has changed over time are not conclusive.1,4,7,19–28

Worldwide fewer than 50% of psychiatric centres on average have ECT. In the United States the percentage of centres which use ECT would vary from 6% in California21 to 55% in the metropolitan area of New York,29 while in Europe ECT is used in 21.5% of hospitals in Belgium,2 51% in France,30 59% in Germany,8 72% in Norway17 and 100% in Denmark.7 The reasons for this enormous degree of variability are highly diverse.1,31,32

Based on these data the warning was given that ECT may be under-used in certain countries and regions, so that some patients would have no access to the best therapeutic options for certain diagnostic indications.1,19 There seems to be no basis for fear of over-using ECT, as using it habitually is ruled out for indications other than those set in the United States.14

The first epidemiological survey on the use of ECT in Spain was published in 1978 by Barcia-Salorio and Martínez-Pardo.33 Bernardo et al.34 in 1990 and Castel et al.35 in 2000 undertook clinical-epidemiological studies on the use of ECT in hospitals. Bernardo et al. carried out the first exhaustive survey in 1996 in the province of Barcelona.36 Martínez-Amorós et al.37 recently published a study on the use of ECT in Catalonia. This concluded that usage rates had risen from 0.57 patients per 10,000 inhabitants-year in 1993 to 1.15 in 2010, an increase of 105%. Almost 15 years ago Bertolín-Guillén et al.38 undertook the first and only national survey on the use of ECT in Spain. They recorded a usage rate in 2000–2001 estimated at 0.61 patients per 10,000 inhabitants-year.

The available information on the use of ECT in Spain as a whole is therefore incomplete and needs updating, so that it is considered to be necessary to carry out a survey covering all of the psychiatric hospital units in Spain39 to estimate the prevalence of use in the different geographical areas, describing how it is used and exploring the causes that may influence its prescription and/or use. This would make it possible to develop guidelines for measures that would help to rationalise its use and guarantee access to the technique under equal conditions.

This article contains some of the results of a survey backed by the SEPB. It centres on the description and evaluation of the use of the technique, as well as territorial variations in use of the same. Other aspects of this work in connection with indications, protocolisation, the framework for use, maintenance, technique and monitoring have been published recently.40

Material and methodsAll hospitals with a psychiatric unit in Spain were surveyed on 31/12/2012, using the 2013 National Catalogue of Hospitals41 and the 2013 Register of the National Statistics Institute.42

Of the 622 hospitals with a psychiatric unit in Spain on 31/12/2012, the only ones included were those catalogued as being for general, psychiatric, psycho-physical rehabilitation and geriatric-long stay care (547 centres). After making this selection the hospitals with a unit specifically for adult psychiatry were identified, and only these were included (222 centres). After reviewing the scientific literature a survey was designed on the use of ECT, with questions agreed by a team of 6 experts in a workgroup on ECT of the Spanish Biological Psychiatry Society. Fieldwork took place from 1/11/13 to 31/05/14 in 5 successive rounds of contacts by post, email and telephone.

Statistical analysisStudy data were recorded in a database designed for this purpose, in compliance with the stipulations of Law 15/1999 on Personal Data Protection. Descriptive analysis was first performed using totals calculation (absolute frequencies) and percentages (relative frequencies) for categorical variables and averages (with their standard deviations) and/or means (with their percentiles) for the quantitative variables. Secondly, comparative analysis was performed using chi-squared tests for qualitative variables and Kruskal–Wallis or Mann–Whitney U tests for continuous variables. Statistical analysis was undertaken using version 17 of the SPSS® statistical programme.

The methodology is described in detail in the article by Vera et al.40

ResultsThe survey was sent to 222 hospitals. The information on hospital characteristics and whether it indicated and/or used ECT was obtained telephonically, so that it is available for 100% of the hospitals. Only 207 hospitals (a response rate of 93.2%) answered the complete questionnaire in writing. As not all of the hospitals answered all of the questions in the survey the size of the sample varies for the different variables analysed.

84.2% of Spanish hospitals used ECT: 54.9% use it in the hospital itself as they have the resources for this, and 29.3% indicate it, although patients are sent to another hospital to be treated as they lack in-house resources. 15.8% did not use ECT: neither applying it nor indicating it.40 The units surveyed had been using ECT for an average of 20.3 years (SD=14.9). There was wide geographical variability in the percentage of hospitals which indicated and/or apply ECT. On the one hand, 100% of the hospitals indicated ECT in the Balearic Islands, Murcia and Cantabria, while fewer than 60% did so in Navarra or La Rioja. On the other hand, 66.7% used it in Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and the Canary Islands, vs 14% in Asturias and Extremadura. In Ceuta and Melilla ECT was neither used nor indicated. ECT was used in 63.7% of public hospitals vs 34.9% of private ones (P=.000), and in 71.9% of general hospitals vs 24.3% of psychiatric hospitals (P=.000).

Among the reasons given for sending patients to other hospitals for treatment, 52 hospitals (91.2%) mentioned lack of material resources, 17 (29.8%) lack of human resources and 6 (10.5%) mentioned the existence of referral agreements with other hospitals. In 3 hospitals (5.3%) patients are sent to another one for ECT as the technique is hardly used. Respecting the reasons given for not even considering indicating the technique, 19 hospitals (59.4%) mentioned the type of patients treated, 9 (28.1%) mentioned the lack of technical resources and 8 (25%) mentioned the lack of agreements or geographical isolation that prevent them from sending patients to other hospitals. 5 hospitals (15.7%) did not consider ECT as they do not believe it is effective.40

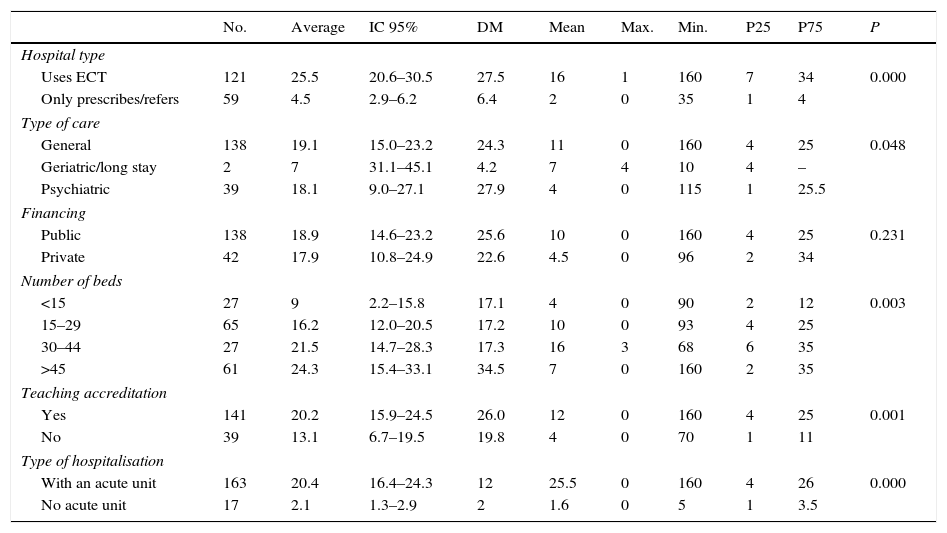

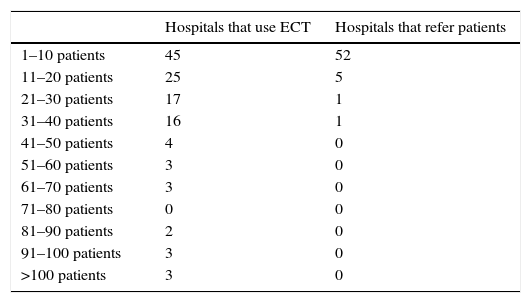

ECT was indicated for an average of 18.7 patients per hospital in 2012 (IC 95% 15.0–22.3). In the hospitals that used ECT the average number of indications per hospital was 25.5 patients (IC 95% 20.6–30.5), and for hospitals that refer patients, 4.5 (IC 95% 2.9–6.2) (P=.000). Nevertheless, the fact that the number of indications by the hospitals that applied ECT included those corresponding to the referring hospitals must be taken into account. Statistically significant differences exist in the number of patients for whom ECT was indicated depending on the autonomous community in question (P=.005), the aim of treatment (P=.048), the number of beds (P=.003), the type of hospitalisation (P=.000) and teaching accreditation (P=.001); this was not the case for type of financing (P=.231). Table 1 shows the number of patients per hospital who were prescribed ECT according to several descriptive variables, and Table 2 shows the number of hospitals where ECT was used or those which refer their patients to receive the treatment.

Number of patients per hospital prescribed electroconvulsive therapy according to several variables (n=180).

| No. | Average | IC 95% | DM | Mean | Max. | Min. | P25 | P75 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital type | ||||||||||

| Uses ECT | 121 | 25.5 | 20.6–30.5 | 27.5 | 16 | 1 | 160 | 7 | 34 | 0.000 |

| Only prescribes/refers | 59 | 4.5 | 2.9–6.2 | 6.4 | 2 | 0 | 35 | 1 | 4 | |

| Type of care | ||||||||||

| General | 138 | 19.1 | 15.0–23.2 | 24.3 | 11 | 0 | 160 | 4 | 25 | 0.048 |

| Geriatric/long stay | 2 | 7 | 31.1–45.1 | 4.2 | 7 | 4 | 10 | 4 | – | |

| Psychiatric | 39 | 18.1 | 9.0–27.1 | 27.9 | 4 | 0 | 115 | 1 | 25.5 | |

| Financing | ||||||||||

| Public | 138 | 18.9 | 14.6–23.2 | 25.6 | 10 | 0 | 160 | 4 | 25 | 0.231 |

| Private | 42 | 17.9 | 10.8–24.9 | 22.6 | 4.5 | 0 | 96 | 2 | 34 | |

| Number of beds | ||||||||||

| <15 | 27 | 9 | 2.2–15.8 | 17.1 | 4 | 0 | 90 | 2 | 12 | 0.003 |

| 15–29 | 65 | 16.2 | 12.0–20.5 | 17.2 | 10 | 0 | 93 | 4 | 25 | |

| 30–44 | 27 | 21.5 | 14.7–28.3 | 17.3 | 16 | 3 | 68 | 6 | 35 | |

| >45 | 61 | 24.3 | 15.4–33.1 | 34.5 | 7 | 0 | 160 | 2 | 35 | |

| Teaching accreditation | ||||||||||

| Yes | 141 | 20.2 | 15.9–24.5 | 26.0 | 12 | 0 | 160 | 4 | 25 | 0.001 |

| No | 39 | 13.1 | 6.7–19.5 | 19.8 | 4 | 0 | 70 | 1 | 11 | |

| Type of hospitalisation | ||||||||||

| With an acute unit | 163 | 20.4 | 16.4–24.3 | 12 | 25.5 | 0 | 160 | 4 | 26 | 0.000 |

| No acute unit | 17 | 2.1 | 1.3–2.9 | 2 | 1.6 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 3.5 | |

DM: diabetes mellitus; IC: interval of confidence; ECT: electroconvulsive therapy.

Number of hospitals which use or refer patients for electroconvulsive therapy per patient number.

| Hospitals that use ECT | Hospitals that refer patients | |

|---|---|---|

| 1–10 patients | 45 | 52 |

| 11–20 patients | 25 | 5 |

| 21–30 patients | 17 | 1 |

| 31–40 patients | 16 | 1 |

| 41–50 patients | 4 | 0 |

| 51–60 patients | 3 | 0 |

| 61–70 patients | 3 | 0 |

| 71–80 patients | 0 | 0 |

| 81–90 patients | 2 | 0 |

| 91–100 patients | 3 | 0 |

| >100 patients | 3 | 0 |

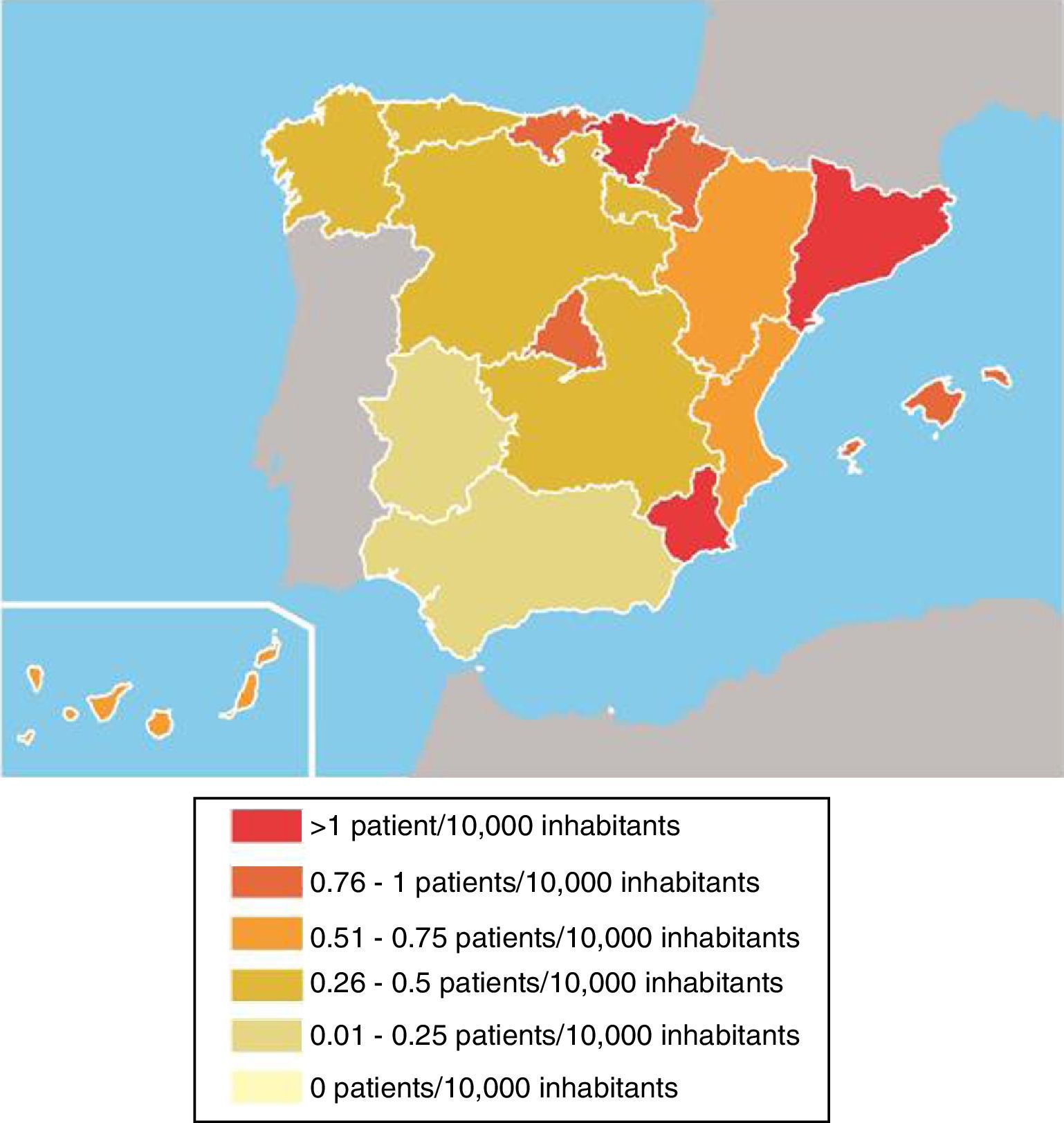

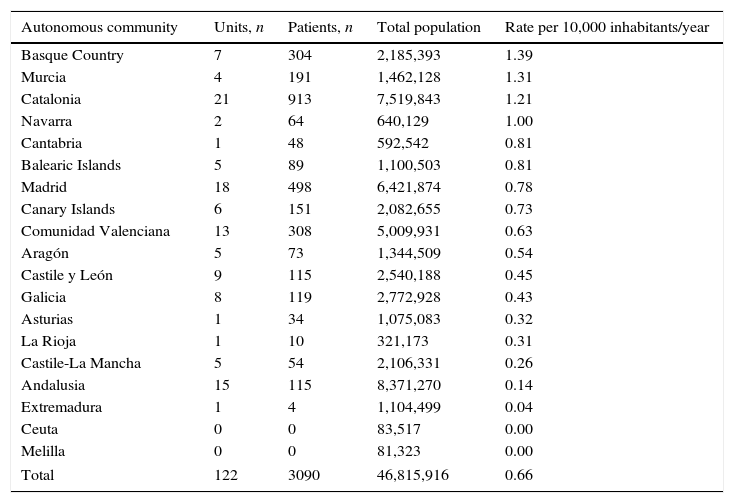

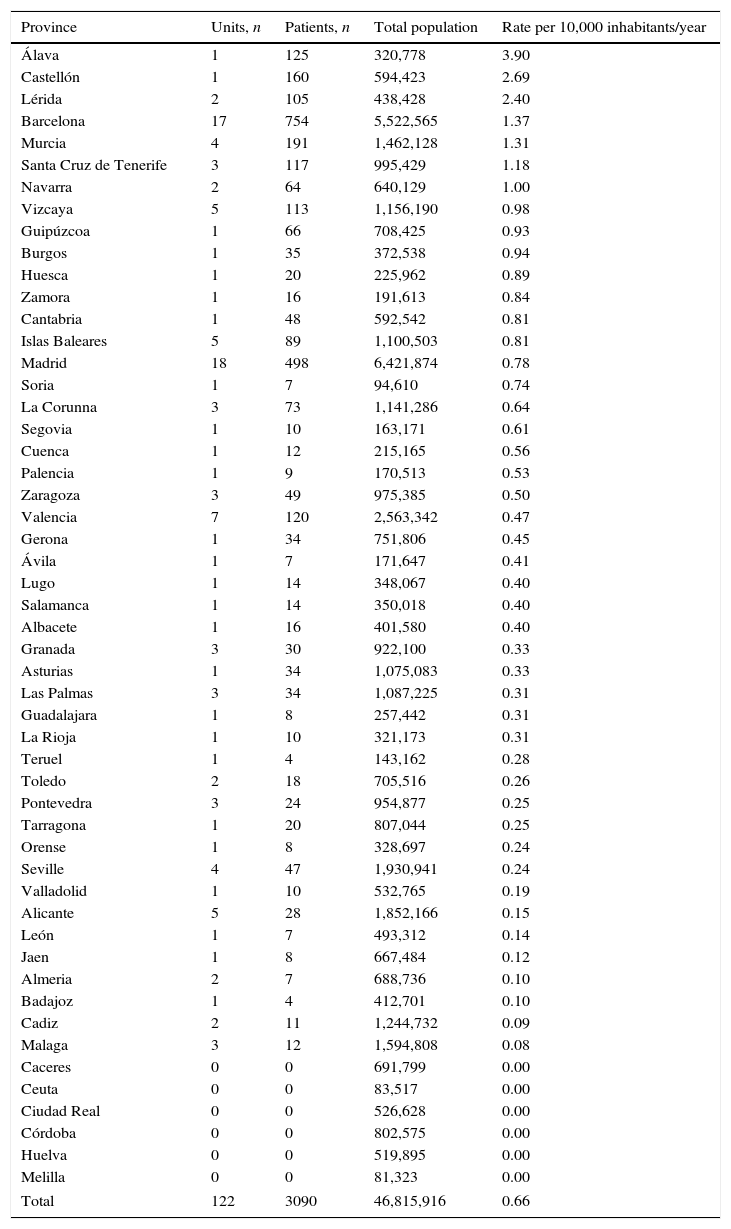

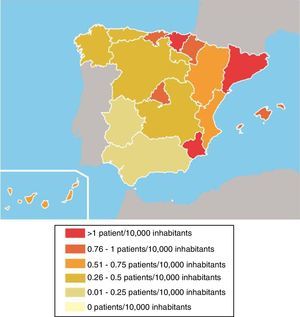

3090 patients were treated using ECT in Spain in 2012, giving a rate of usage of 0.66 patients per 10,000 inhabitants-year. This rate differs significantly between the different autonomous communities. Thus in the Basque Country, Murcia and Catalonia more than 1.2 patients per 10,000 inhabitants-year received ECT, vs fewer than 0.3 in Andalusia, Castile-La Mancha and Extremadura (Table 3 and Fig. 1). There are also marked differences between provinces in terms of rates of ECT usage. Thus for example, more than 2.3 patients per 10,000 inhabitants-year received ECT in 2012 in Álava, Castellón or Lérida, while ECT was not used in Caceres, Córdoba, Ciudad Real, Huelva or the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla (Table 4).

Number of units that use electroconvulsive therapy, number of patients who received it and usage rate per autonomous community.

| Autonomous community | Units, n | Patients, n | Total population | Rate per 10,000 inhabitants/year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basque Country | 7 | 304 | 2,185,393 | 1.39 |

| Murcia | 4 | 191 | 1,462,128 | 1.31 |

| Catalonia | 21 | 913 | 7,519,843 | 1.21 |

| Navarra | 2 | 64 | 640,129 | 1.00 |

| Cantabria | 1 | 48 | 592,542 | 0.81 |

| Balearic Islands | 5 | 89 | 1,100,503 | 0.81 |

| Madrid | 18 | 498 | 6,421,874 | 0.78 |

| Canary Islands | 6 | 151 | 2,082,655 | 0.73 |

| Comunidad Valenciana | 13 | 308 | 5,009,931 | 0.63 |

| Aragón | 5 | 73 | 1,344,509 | 0.54 |

| Castile y León | 9 | 115 | 2,540,188 | 0.45 |

| Galicia | 8 | 119 | 2,772,928 | 0.43 |

| Asturias | 1 | 34 | 1,075,083 | 0.32 |

| La Rioja | 1 | 10 | 321,173 | 0.31 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 5 | 54 | 2,106,331 | 0.26 |

| Andalusia | 15 | 115 | 8,371,270 | 0.14 |

| Extremadura | 1 | 4 | 1,104,499 | 0.04 |

| Ceuta | 0 | 0 | 83,517 | 0.00 |

| Melilla | 0 | 0 | 81,323 | 0.00 |

| Total | 122 | 3090 | 46,815,916 | 0.66 |

Number of hospitalisation units that use electroconvulsive therapy, number of patients who received it and application rate per province.

| Province | Units, n | Patients, n | Total population | Rate per 10,000 inhabitants/year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Álava | 1 | 125 | 320,778 | 3.90 |

| Castellón | 1 | 160 | 594,423 | 2.69 |

| Lérida | 2 | 105 | 438,428 | 2.40 |

| Barcelona | 17 | 754 | 5,522,565 | 1.37 |

| Murcia | 4 | 191 | 1,462,128 | 1.31 |

| Santa Cruz de Tenerife | 3 | 117 | 995,429 | 1.18 |

| Navarra | 2 | 64 | 640,129 | 1.00 |

| Vizcaya | 5 | 113 | 1,156,190 | 0.98 |

| Guipúzcoa | 1 | 66 | 708,425 | 0.93 |

| Burgos | 1 | 35 | 372,538 | 0.94 |

| Huesca | 1 | 20 | 225,962 | 0.89 |

| Zamora | 1 | 16 | 191,613 | 0.84 |

| Cantabria | 1 | 48 | 592,542 | 0.81 |

| Islas Baleares | 5 | 89 | 1,100,503 | 0.81 |

| Madrid | 18 | 498 | 6,421,874 | 0.78 |

| Soria | 1 | 7 | 94,610 | 0.74 |

| La Corunna | 3 | 73 | 1,141,286 | 0.64 |

| Segovia | 1 | 10 | 163,171 | 0.61 |

| Cuenca | 1 | 12 | 215,165 | 0.56 |

| Palencia | 1 | 9 | 170,513 | 0.53 |

| Zaragoza | 3 | 49 | 975,385 | 0.50 |

| Valencia | 7 | 120 | 2,563,342 | 0.47 |

| Gerona | 1 | 34 | 751,806 | 0.45 |

| Ávila | 1 | 7 | 171,647 | 0.41 |

| Lugo | 1 | 14 | 348,067 | 0.40 |

| Salamanca | 1 | 14 | 350,018 | 0.40 |

| Albacete | 1 | 16 | 401,580 | 0.40 |

| Granada | 3 | 30 | 922,100 | 0.33 |

| Asturias | 1 | 34 | 1,075,083 | 0.33 |

| Las Palmas | 3 | 34 | 1,087,225 | 0.31 |

| Guadalajara | 1 | 8 | 257,442 | 0.31 |

| La Rioja | 1 | 10 | 321,173 | 0.31 |

| Teruel | 1 | 4 | 143,162 | 0.28 |

| Toledo | 2 | 18 | 705,516 | 0.26 |

| Pontevedra | 3 | 24 | 954,877 | 0.25 |

| Tarragona | 1 | 20 | 807,044 | 0.25 |

| Orense | 1 | 8 | 328,697 | 0.24 |

| Seville | 4 | 47 | 1,930,941 | 0.24 |

| Valladolid | 1 | 10 | 532,765 | 0.19 |

| Alicante | 5 | 28 | 1,852,166 | 0.15 |

| León | 1 | 7 | 493,312 | 0.14 |

| Jaen | 1 | 8 | 667,484 | 0.12 |

| Almeria | 2 | 7 | 688,736 | 0.10 |

| Badajoz | 1 | 4 | 412,701 | 0.10 |

| Cadiz | 2 | 11 | 1,244,732 | 0.09 |

| Malaga | 3 | 12 | 1,594,808 | 0.08 |

| Caceres | 0 | 0 | 691,799 | 0.00 |

| Ceuta | 0 | 0 | 83,517 | 0.00 |

| Ciudad Real | 0 | 0 | 526,628 | 0.00 |

| Córdoba | 0 | 0 | 802,575 | 0.00 |

| Huelva | 0 | 0 | 519,895 | 0.00 |

| Melilla | 0 | 0 | 81,323 | 0.00 |

| Total | 122 | 3090 | 46,815,916 | 0.66 |

The survey included all of the psychiatric hospitalisation units in Spain that were working during the period studied. 100% of the hospitals included supplied the information on hospital characteristics by telephone, as well as whether the hospital indicated and/or used ECT, giving the results of our study firm internal and external validity. Nevertheless, the information was obtained using a survey rather than a clinical audit, so that this may limit data reliability.29

The percentage of hospitals with psychiatric hospitalisation that use ECT in Spain as a whole increased from 46.4% in 2000–200138 to 54.9% in 2012. Spain is therefore among the countries with a higher percentage of units with ECT and a tendency to increase, as opposed to international data as a whole.1 In Catalonia the percentage of hospitals that use ECT also increased, from 60% in 199336 to 80% in 2012.37 Geographical access to the treatment would be another decisive factor in the percentage of hospitals which refer cases to other units for ECT, and this has remained relatively stable in Spain. ECT was therefore available for 84.2% of hospitals in Spain in 2012, as opposed to 74.7% in 2000–2001.38

In spite of this high proportion of hospitals with ECT, the rate of use in Spain remains among the lowest in Western countries,1,3–7,17,43,44 and its increase in one decade was minimum: from 0.61 patients per 10,000 inhabitants-year in 2000–200138 to 0.66 in 2012. Worldwide evidence seems to indicate that its use is declining in regions where ECT had been widely used beforehand,4,20,21,45,46 although it would have stabilised or even increased in regions where it hardly been used beforehand,26,28,37 reducing variability between neighbouring regions.7,27,47,48 In recent years the publication of conclusive reports on the efficacy and safety of ECT for specific clinical indications may be contributing to slowing down this fall in its use.25 It would be desirable to clarify the degree to which the ECT usage rate in our country corresponds to the optimum frequency of use of this technique.

The reasons for not indicating ECT are similar to those previously mentioned in our area.8,17,38,49 The main reason given for not prescribing it was the lack of a clinical indication in hospitals that only treat chronic patients (59.4%), followed by the lack of human and/or material resources (28.1%). However, although this is a plausible explanation for not using the technique, this is not the case for prescribing it and referring patients to be treated elsewhere. This may therefore be more of a euphemistic answer than it is a real difficulty.37 If this flow of patients with a clinical indication really is an administrative problem (referred to explicitly by 1 of every 4 Spanish hospitals) then this is a serious resource management problem. 15.7% of the hospitals that do not consider the technique because they do not believe that it is effective display a serious problem in their level of information.

In any case, it is clear that the frequency with which this procedure is indicated is notably lower in hospitals that lack ECT facilities. Thus in almost 70% of these hospitals fewer than 5 patients per year were referred for ECT treatment, and none were referred in almost 15% of these hospitals. This low number of referrals may be due to a real lack of patients with indications for ECT. This would have led these hospitals to opt for referring them due to reasons of cost-effectiveness, but only 5.3% of the hospitals in our study mentioned this reasons for not using the technique. It is therefore more probable that the lack of available ECT in these hospitals means that it is reserved as a last line treatment for patients after the failure of all other therapeutic options, leading to a sub-optimum use of this treatment.

Regarding the degree to which there is equal access to the technique, notable variations between regions were found in rates of ECT usage. This is also the case in other countries in our area.2,5,14,17 Thus for example, a Basque citizen would have 35 times more probability of receiving ECT than someone in Extremadura; and while ECT was used to treat more than 100 patients in provinces that are not densely populated such as Álava, Castellón or Lérida in 2012, in others such as Caceres, Córdoba, Ciudad Real, Huelva, Ceuta or Melilla, ECT was not given to a single patient. This variability is notable even among the different provinces in a single autonomous community. Thus for example the ECT usage rate would amount to 2.69 patients per 10,000 inhabitants-year in Castellón, vs 0.15 in Alicante; 2.40 en Lérida vs 0.41 in Gerona, or 1.18 in Santa Cruz de Tenerife vs 0.31 in Las Palmas.

The number of patients who receive ECT also varies widely between different hospitals. It was therefore used for more than 100 patients per year in 3 hospitals, more than 75 patients in 8 hospitals and more than 50 patients in 14 hospitals. It is probable that this can be explained by greater compliance with the recommendation in clinical practice guides (CPG) and/or the centralisation of ECT use in certain hospitals, although the need to rule out the over-use of ECT in specific teams of professionals has also been raised.14 On the contrary, ECT was used in a very low number of patients in the majority of the hospitals: fewer than 5 patients per year in 21 hospitals and fewer than 10 in 45 hospitals. These data show that discussion is required with all of the necessary care and also the greatest possible clarity about the efficiency and level of technical training in units with low levels of activity.

We therefore find a high proportion of hospitals with ECT in Spain as a whole, although they are distributed in an enormously heterogeneous way among autonomous communities and provinces. Additionally, the majority of the large number of hospitals where the technique is available use it infrequently, giving rise to rate of usage far lower than levels that are usual in similar countries.

It seems to be necessary for the bodies in charge of planning healthcare to determine how many units and professionals are needed to meet the demands for ECT in each region (as has normally been done in Spain for services and referral unit for other specialities and techniques), while clearly defining the mechanisms for referral from hospitals which are unable to apply the technique. The aim will be to improve the cost-effectiveness ratio of the procedure by ensuring universal accessibility and equal opportunities for the whole population, while also – following the above-mentioned model – increasing the level of training in the units established. It has been suggested that regional ECT units would make it possible to reduce the costs of using it, while also favouring a higher level of professional specialisation and experience.39,45,50 Together with the implementation of ECT unit accreditation processes, this would make it possible to ensure compliance with minimum quality standards when applying ECT, as is the case in other countries in our area.39

The variability described in the use of ECT, even between geographically close regions with very similar healthcare and social situations, and even different hospitals in the same region, means that it is improbable that the cause of this lies in differences between populations. Differences in the prevalence of psychiatric disorders, different forms of organising healthcare services or economic inequalities can also be ruled out. Given the absence of legal restrictions that govern the use of the technique in our country, the variation in usage of the same may be due to the high level of heterogeneity in psychiatrists’ criteria for using ECT vs other psychiatric treatments.10,14 This may be connected with the lack of updated knowledge about ECT that continues to exist among healthcare professionals.37,51 In our study about 15% of the hospitals continued to base their refusal to prescribe it on its lack of clinical efficacy, in spite of the firm evidence now available for the effectiveness of ECT for certain indications. CPG therefore emerged as an attempt to make the use of ECT uniform and optimise clinical practice, with the final aim of improving patient care quality. A CPG was recently published in Catalonia,52 but the Spanish Consensus on ECT53 was approved 15 years ago. It therefore seems pertinent to reach consensus on the available evidence in a new CPG promoted by all healthcare authorities and relevant scientific associations, as well as publishing the approved recommendations to facilitate their implementation by psychiatrists.39

Likewise, it is necessary to encourage and protocolise training in ECT for all of the professionals involved in prescribing and/or using it, given that the implementation of specific training programmes is effective for improving knowledge about ECT and making attitudes to it more positive among professionals.36,37,54–57

To summarise, the percentage of hospitals that use ECT has risen during recent years in Spain. Nevertheless, it is still hardly used, and the rate of usage here is one of the lowest in western countries. Distribution and access to the technique vary extremely widely, and this together with the variability of training and usage criteria of professionals does not guarantee equality in access to the technique among the patients who fulfil the criteria for this indication. It therefore seems necessary to implement healthcare planning measures to optimise the cost-effectiveness ratio of the procedure and ensure it is equally accessible in different regions, as well as developing accreditation procedures for ECT units, reaching agreement on the evidence in a new CPG and continuing to train all of the professionals involved in prescribing it and/or applying it.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments with human beings or animals took place for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data are shown in this paper.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data are shown in this paper.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors would like to thank the Spanish Biological Psychiatry Society for the logistic help in undertaking this study, Dr. Nerea Egües Olazábal for her contribution to the statistical analysis of the data, and all of the professionals who patiently answered the survey; this work would not have been possible without them.

Please cite this article as: Sanz-Fuentenebro J, Vera I, Verdura E, Urretavizcaya M, Martínez-Amorós E, Soria V, et al. Patrón de uso de la terapia electroconvulsiva en España: propuestas para una práctica óptima y un acceso equitativo. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2017;10:87–95