To analyze the possible relationship between dementia in the elderly and the subsequent development of suicide ideation, attempts and/or completed suicides.

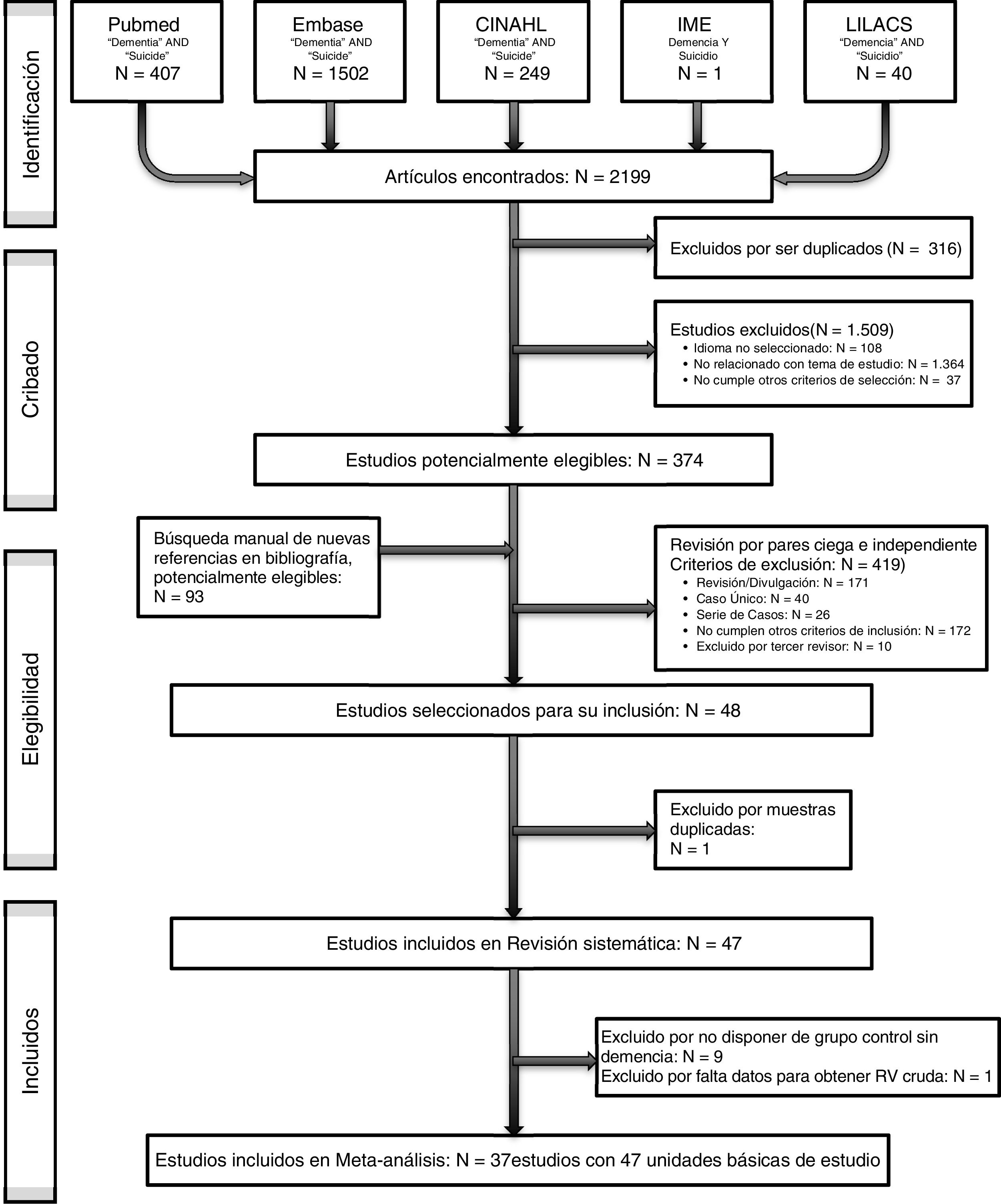

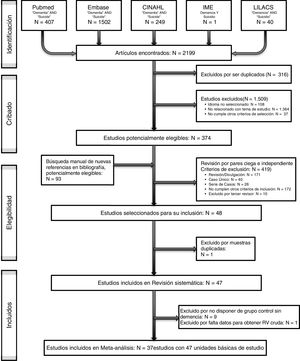

MethodsSystematic review and meta-analysis. Selection criteria: studies that analyzed the relationship between dementia and suicide. Search strategy: (i) in PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, IME and Lilacs until December 2018; (ii) manual search of the bibliography of selected articles; (iii) contact with leading authors. Article selection and data extraction according to a predefined protocol, including bias risk assessment, were performed by independent peer reviewers. The effect size index was calculated using Odds Ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (random-effects model). Heterogeneity was evaluated with forest plots, Cochran's Q and I2 index. Assessment of publication bias using funnel plots (“trim-and-fill” method) and the Egger test. The analysis of moderating variables was performed using a multiple meta-regression under a mixed-effects model.

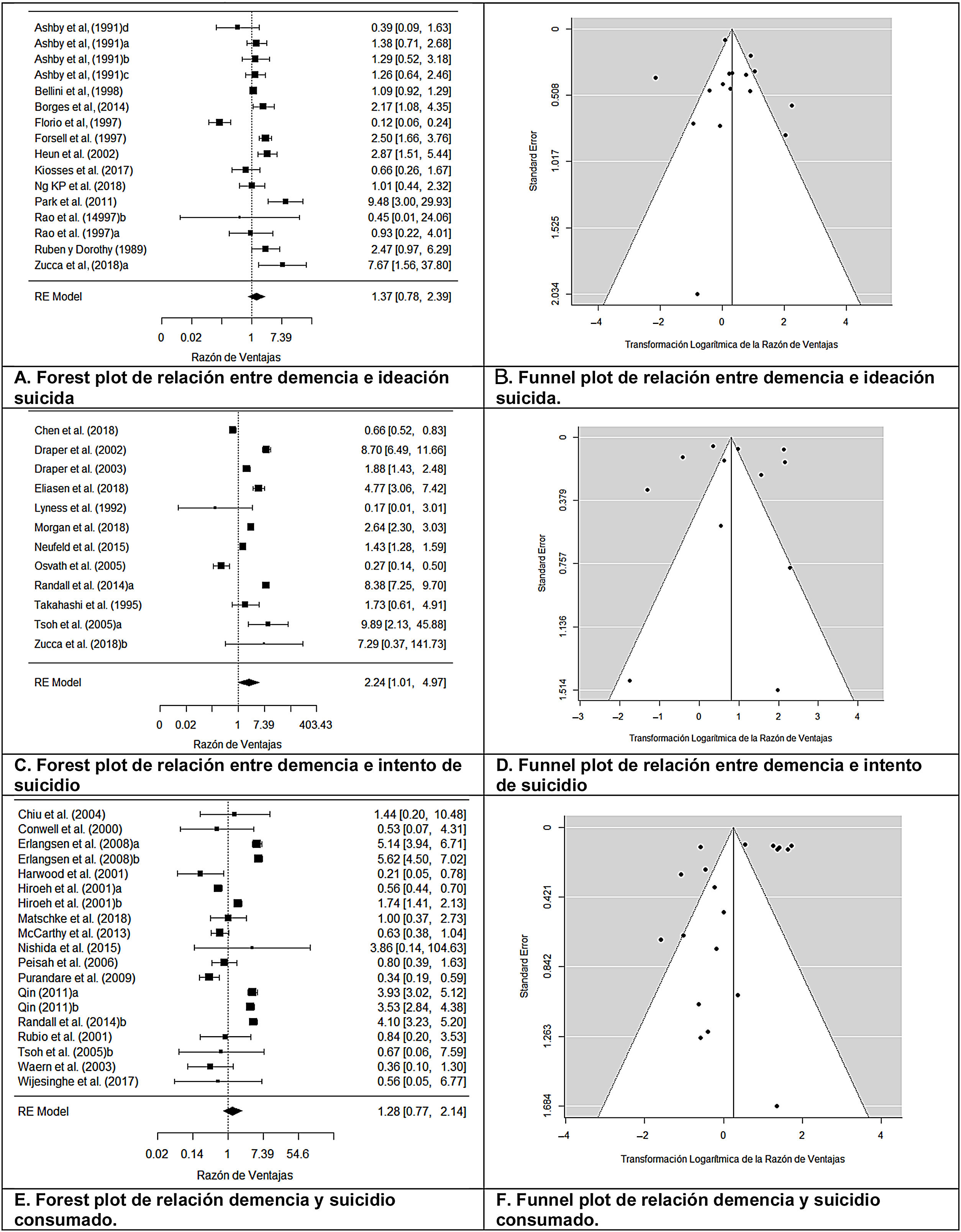

Results37 studies and 47 basic units of study were identified. Effect size of the association of dementia with: Suicidal Ideation OR=1.37 (95% CI: .78–2.39); Suicide Attempt: OR=2.24 (95% CI: 1.01–4.97); and Completed Suicide: OR=1.28 (95% CI: .77–2.14). Possible publication bias was ruled out.

ConclusionsA trend toward suicidal events is identified, especially suicide attempts in people with dementia. Greater attention and care are recommended after a recent diagnosis of dementia, especially with adequate assessment of comorbidities, which could influence the occurrence and outcome of suicidal events.

Analizar la posible relación entre demencia en el anciano y el posterior desarrollo de ideas, intentos y/o suicidios consumados.

MétodosRevisión sistemática y metaanálisis. Criterios de selección: estudios que analizaran la relación entre demencia y suicidio. Estrategia de búsqueda: i) en PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, IME y LILACS hasta diciembre de 2018; ii) búsqueda manual de la bibliografía de artículos seleccionados; iii) contacto con principales autores. Revisión independiente por pares para la selección de artículos y extracción de datos según protocolo de registro, incluyendo la evaluación del riesgo de sesgos. Cálculo del índice del tamaño del efecto mediante razón de ventajas (RV) y su intervalo de confianza del 95% (IC 95%) (modelo de efectos aleatorios). La heterogeneidad se evaluó con forest plots, Q de Cochran e índice I2. Valoración del sesgo de publicación mediante funnel plots (método «trim-and-fill») y el test de Egger. El análisis de variables moderadoras se realizó mediante un modelo de metarregresión múltiple de efectos mixtos.

ResultadosSe identificaron 37 estudios y 47 unidades básicas de estudio. Tamaño del efecto de la asociación de demencia con: ideación suicida RV=1,37 (IC 95%: 0,78-2,39); intento de suicidio: RV=2,24 (IC 95%: 1,01-4,97); y suicidio consumado: RV=1,28 (IC 95%: 0,77-2,14). Se descartó un posible sesgo de publicación.

ConclusionesSe identifica una tendencia hacia la aparición de eventos suicidas, especialmente intento de suicidio en personas con demencia. Sería recomendable una mayor atención y cuidado tras un diagnóstico reciente de demencia, especialmente con adecuada valoración de comorbilidades, que pudieran influir en aparición y desenlace de eventos suicidas.

Suicide is the primary cause of violent death today, accounting for approximately one million deaths worldwide per year. This has become a major public health problem, and is particularly relevant in our environment due to its consequences on a personal, family, social and economic level.1–4 Suicide is among the 10 first causes of death in the general population5 and is the second/third cause of deaths in people between 15 and 44 years of age.3,5 According to the WHO reports, there is a rising trend in suicide rates, and it may account for up to 1.53 million deaths in 2020, worldwide.4,6 In Spain, between 1991 and 2008, the number of suicides was 60,176 (75.4% men), which represented .93% of deaths during this period, 8.7 per 100.000 inhabitants in 2016.7 Suicide rates are higher in men than in women.8

The suicide rate is highly variable among the different countries due to many factors such sociocultural variables and although a standardized global rate by age has been calculated for all countries of 10.5 per 100,000 inhabitants, in 2016,9 the rates ranged from figures under 5 per 100,000 inhabitants in countries like Morocco or Indonesia to figures above 17 per 100,000 in countries, such as France or Russia.7 However, it should be noted that only in 80 of the 183 Member States of the WHO were data registers of sound quality available in 2016.9

Despite the high variability, the grouping of international data published by the WHO reveals that completed suicide by age in almost all countries has been constantly increasing.10 Regarding age groups, those with the highest percentage of suicide attempts and/or completed suicide throughout life are in teenagers and young adults, where death by suicide reaches the highest absolute rates.11 However, in advanced ages, suicide rates are, in relative numbers, up to 8 times higher than in other age groups, not least because of the use of more lethal methods.8,11,12

The rate of dementia rises with age and is a prevalent disease in the eldery.13,14 Dementia is normally associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms such as depression, psychosis and anxiety,15 all of which are considered to be risk factors in suicide, but the role exercised by dementia as an independent risk factor for suicide is unknown.16 As far as we know, no meta-analyses have been published on the association between dementia and suicidal behavior. The aim of this study was to assess the magnitude of this association, and to identify the moderating variables of this association.

Material and methodsDesignSystematic review and meta-analysis. This study was written in accordance with the PRISMA declaration (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Metanalyses).17

Search strategyThe search was conducted in: Pubmed, EMBASE, CINAHL, IME and LILACS using the following search terms: [Dementia] AND [Suicide] (or [Dementia] and [Suicide] in IME and LILACS). Published articles were included up until 31st December 2018. No limits or restrictions were imposed on this search. Bibliographical references of the potentially eligible articles were analyzed and an attempt was made to contact the most relevant authors to identify additional studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaInclusion criteria were: (a) empirical study on the relationship between dementia and suicide, (b) observational analytical type study (cases and controls or cohorts) or descriptive (cross-sectional), (c) inclusion of a comparison group and (d) written in English, French, Italian, Portuguese or Spanish. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) type studies: single case, case series, reviews, or outreach articles and (b) those which do not specifically analyze the relationship between dementia and suicide. Two researchers (FJAM and PGM) reviewed the articles separately, for possible study inclusion. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus between the reviewers, and if disagreement persisted, the study was analyzed by the senior researcher (FNM and JSM), to decide whether it should be included in the review or not.

Data collectionThe studies which finally link criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis were analyzed by complete text and independently, by 2 reviewers (FJAM and PGM), for extraction of all the data collected in the previously defined recording protocol, which included: extrinsic variables: number of authors, year of publication, financing and conflict of interests; substantive variables: country and sample characteristics (total sample size and of the group with dementia, distribution by sex, by age, origin); methodological variable: design and study aims, elements of quality, elements relating to dementia diagnosis (form of diagnosis, types, stages of disease progression, presence of comorbidity) and with suicide evaluation (number of events, type of event: ideation, attempted suicide or completed suicide and form of measuring event); outcome variables: measurement of the effect size used and expression of the results using odds ratio (OR) and confidence interval (CI), directly supplied or calculated from the study. When discrepancies appeared, they were resolved by consensus, or, if they persisted, through review by a senior researcher (FNM and JSM).

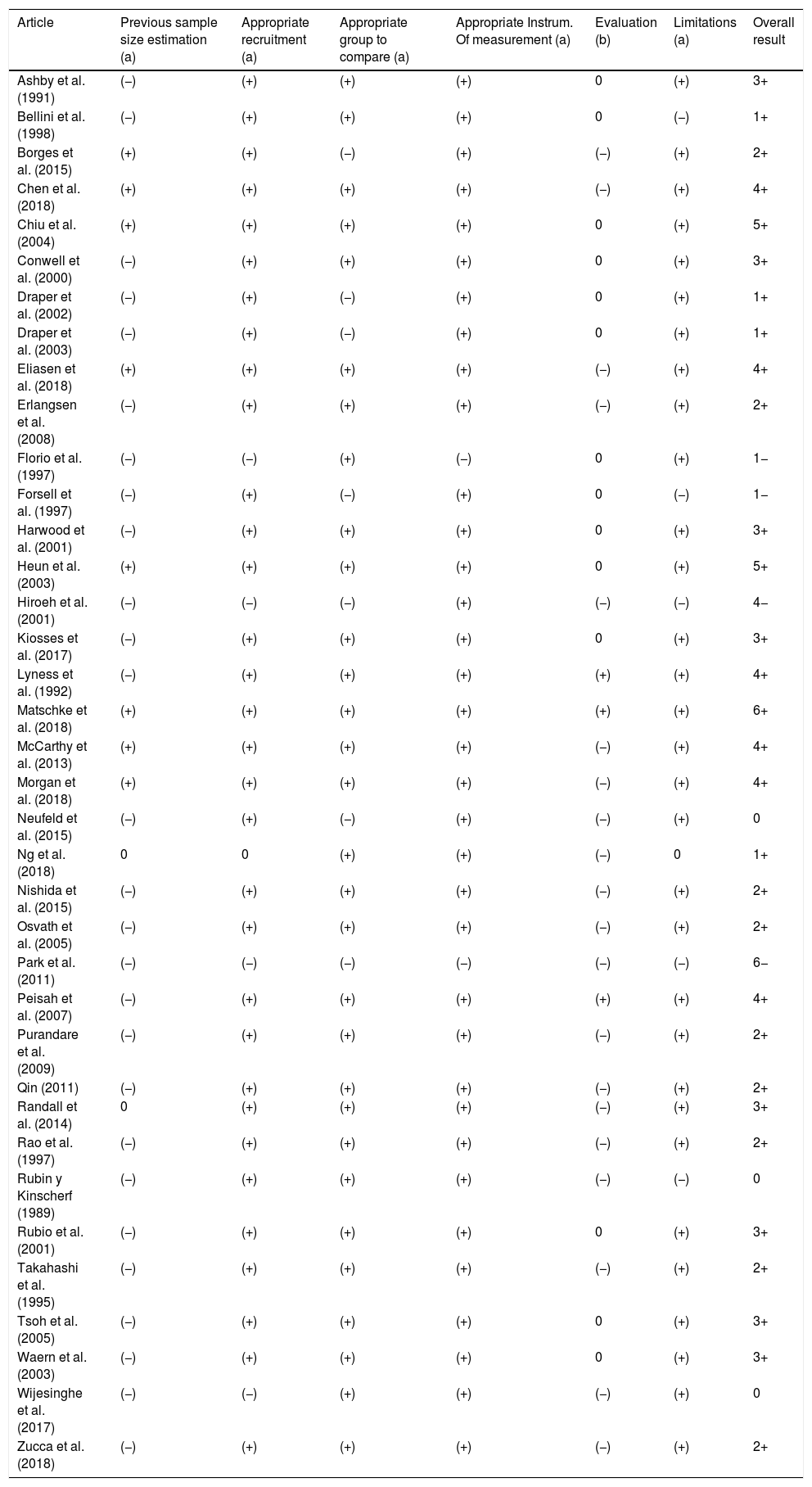

Methodological quality and bias riskTo assess quality and analyze the existence of limitations, possible bias and other factors of confusion which could have affected overall results of this study, and following the review of difference scales (STROBE, NOS, Berra et al., Jarde et al., Kmet et al.),4,18–22 an ad hoc scale was designed which was included in the data extraction protocol, to assess the presence of the following items: (a) calculation prior to sample size; (b) recruitment in keeping with the sample; (c) existence of an appropriate sample for group comparison; (d) use of appropriate instruments of measurement; (e) existence of a correct assessment (independent and/or blind); (f) discussion on possible limitations which could affect study results. The possible results of each item would be: (+) fulfills; (0) partially fulfills or does not provide said information; (−) does not fulfill. The range of study quality level would be between ±6.

Statistical analysisThree meta-analyses were conducted, one for each dependent variable studied: suicidal ideation, attempted suicide and completed suicide. The effect size index used to quantify the relationship between dementia and the 3 dependent variables studied was the OR. When the study did not directly provide the OR, it was calculated according to included data. The mean effect size (OR+), its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and its statistical significance applying the method proposed by Hartung.23,24 Prior to meta-analytic integration the OR were transformed to natural logarithm (nL) in order to normalize its distribution and stabilize its variance. After analysis, the values were again transformed to the OR metric to aid interpretation. The meta-analytical calculations were made by accepting a model of random effects, since high heterogeneity was expected in the original studies.24,25 To examine heterogeneity of side effects forest plots were constructed and Cochran's Q statistic I2.26,27 Index was calculated. To assess whether publication bias could threaten the validity of meta-analytical results, funnel plots were constructed by applying “trim-and-fill” Duval and Tweedie method28 of lost data imputation and the Egger test.29

Additional analysis consisted in examining the possible influx of quantitative and qualitative moderating variables on the OR, on the assumption of mixed effect models. For each moderating or predictor variable the F statistic was calculated to contrast its statistical significance, the QE statistic to inform of specification effort and the percentage of explained variance, R2. ANOVA was applied to examine possible association of qualitative moderating variables and meta-regressions using the improved method proposed by Knapp and Hartung30–32 for analysis of continuous moderating variables. Lastly, a multiple meta-regression model was applied to include the subset of the most relevant moderating variables which would explain the variability of the OR. All statistical analyses were performed in R with the metafor33 package.

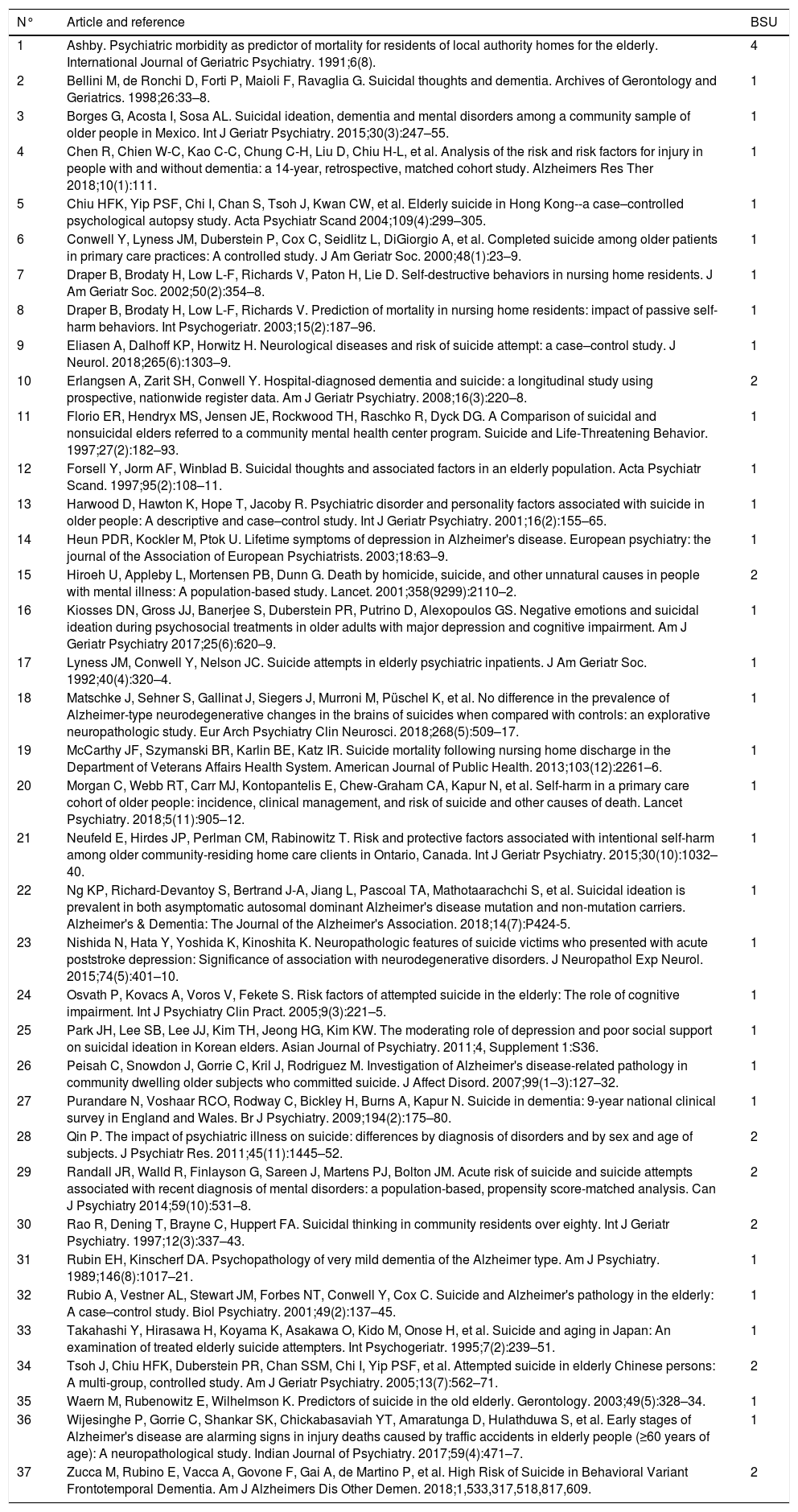

ResultsThe search and select process of articles is contained in Fig. 1. Out of the 467 potentially eligible articles (initial search, further manual review of the literature and/or contact with authors) 37 articles were finally included (Table 1). In total, the selected studies provided a total of 47 basic study units (BSU). During the selection process of articles and data extraction, agreement between reviewers was 92.48%. The remaining 7.52% was resolved by consensual discussion, and the intervention of the third reviewer was required in 4 cases of discrepancy (.067%). Mean quality of the studies was a value of +2, with a standard deviation of 2.32 (Table 2).

Articles and their basic study units (BSU) included in meta-analysis.

| N° | Article and reference | BSU |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ashby. Psychiatric morbidity as predictor of mortality for residents of local authority homes for the elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1991;6(8). | 4 |

| 2 | Bellini M, de Ronchi D, Forti P, Maioli F, Ravaglia G. Suicidal thoughts and dementia. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 1998;26:33–8. | 1 |

| 3 | Borges G, Acosta I, Sosa AL. Suicidal ideation, dementia and mental disorders among a community sample of older people in Mexico. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(3):247–55. | 1 |

| 4 | Chen R, Chien W-C, Kao C-C, Chung C-H, Liu D, Chiu H-L, et al. Analysis of the risk and risk factors for injury in people with and without dementia: a 14-year, retrospective, matched cohort study. Alzheimers Res Ther 2018;10(1):111. | 1 |

| 5 | Chiu HFK, Yip PSF, Chi I, Chan S, Tsoh J, Kwan CW, et al. Elderly suicide in Hong Kong--a case–controlled psychological autopsy study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004;109(4):299–305. | 1 |

| 6 | Conwell Y, Lyness JM, Duberstein P, Cox C, Seidlitz L, DiGiorgio A, et al. Completed suicide among older patients in primary care practices: A controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(1):23–9. | 1 |

| 7 | Draper B, Brodaty H, Low L-F, Richards V, Paton H, Lie D. Self-destructive behaviors in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(2):354–8. | 1 |

| 8 | Draper B, Brodaty H, Low L-F, Richards V. Prediction of mortality in nursing home residents: impact of passive self-harm behaviors. Int Psychogeriatr. 2003;15(2):187–96. | 1 |

| 9 | Eliasen A, Dalhoff KP, Horwitz H. Neurological diseases and risk of suicide attempt: a case–control study. J Neurol. 2018;265(6):1303–9. | 1 |

| 10 | Erlangsen A, Zarit SH, Conwell Y. Hospital-diagnosed dementia and suicide: a longitudinal study using prospective, nationwide register data. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(3):220–8. | 2 |

| 11 | Florio ER, Hendryx MS, Jensen JE, Rockwood TH, Raschko R, Dyck DG. A Comparison of suicidal and nonsuicidal elders referred to a community mental health center program. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1997;27(2):182–93. | 1 |

| 12 | Forsell Y, Jorm AF, Winblad B. Suicidal thoughts and associated factors in an elderly population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;95(2):108–11. | 1 |

| 13 | Harwood D, Hawton K, Hope T, Jacoby R. Psychiatric disorder and personality factors associated with suicide in older people: A descriptive and case–control study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(2):155–65. | 1 |

| 14 | Heun PDR, Kockler M, Ptok U. Lifetime symptoms of depression in Alzheimer's disease. European psychiatry: the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists. 2003;18:63–9. | 1 |

| 15 | Hiroeh U, Appleby L, Mortensen PB, Dunn G. Death by homicide, suicide, and other unnatural causes in people with mental illness: A population-based study. Lancet. 2001;358(9299):2110–2. | 2 |

| 16 | Kiosses DN, Gross JJ, Banerjee S, Duberstein PR, Putrino D, Alexopoulos GS. Negative emotions and suicidal ideation during psychosocial treatments in older adults with major depression and cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017;25(6):620–9. | 1 |

| 17 | Lyness JM, Conwell Y, Nelson JC. Suicide attempts in elderly psychiatric inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(4):320–4. | 1 |

| 18 | Matschke J, Sehner S, Gallinat J, Siegers J, Murroni M, Püschel K, et al. No difference in the prevalence of Alzheimer-type neurodegenerative changes in the brains of suicides when compared with controls: an explorative neuropathologic study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;268(5):509–17. | 1 |

| 19 | McCarthy JF, Szymanski BR, Karlin BE, Katz IR. Suicide mortality following nursing home discharge in the Department of Veterans Affairs Health System. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(12):2261–6. | 1 |

| 20 | Morgan C, Webb RT, Carr MJ, Kontopantelis E, Chew-Graham CA, Kapur N, et al. Self-harm in a primary care cohort of older people: incidence, clinical management, and risk of suicide and other causes of death. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(11):905–12. | 1 |

| 21 | Neufeld E, Hirdes JP, Perlman CM, Rabinowitz T. Risk and protective factors associated with intentional self-harm among older community-residing home care clients in Ontario, Canada. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(10):1032–40. | 1 |

| 22 | Ng KP, Richard-Devantoy S, Bertrand J-A, Jiang L, Pascoal TA, Mathotaarachchi S, et al. Suicidal ideation is prevalent in both asymptomatic autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease mutation and non-mutation carriers. Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2018;14(7):P424-5. | 1 |

| 23 | Nishida N, Hata Y, Yoshida K, Kinoshita K. Neuropathologic features of suicide victims who presented with acute poststroke depression: Significance of association with neurodegenerative disorders. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2015;74(5):401–10. | 1 |

| 24 | Osvath P, Kovacs A, Voros V, Fekete S. Risk factors of attempted suicide in the elderly: The role of cognitive impairment. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2005;9(3):221–5. | 1 |

| 25 | Park JH, Lee SB, Lee JJ, Kim TH, Jeong HG, Kim KW. The moderating role of depression and poor social support on suicidal ideation in Korean elders. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;4, Supplement 1:S36. | 1 |

| 26 | Peisah C, Snowdon J, Gorrie C, Kril J, Rodriguez M. Investigation of Alzheimer's disease-related pathology in community dwelling older subjects who committed suicide. J Affect Disord. 2007;99(1–3):127–32. | 1 |

| 27 | Purandare N, Voshaar RCO, Rodway C, Bickley H, Burns A, Kapur N. Suicide in dementia: 9-year national clinical survey in England and Wales. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(2):175–80. | 1 |

| 28 | Qin P. The impact of psychiatric illness on suicide: differences by diagnosis of disorders and by sex and age of subjects. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(11):1445–52. | 2 |

| 29 | Randall JR, Walld R, Finlayson G, Sareen J, Martens PJ, Bolton JM. Acute risk of suicide and suicide attempts associated with recent diagnosis of mental disorders: a population-based, propensity score-matched analysis. Can J Psychiatry 2014;59(10):531–8. | 2 |

| 30 | Rao R, Dening T, Brayne C, Huppert FA. Suicidal thinking in community residents over eighty. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12(3):337–43. | 2 |

| 31 | Rubin EH, Kinscherf DA. Psychopathology of very mild dementia of the Alzheimer type. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146(8):1017–21. | 1 |

| 32 | Rubio A, Vestner AL, Stewart JM, Forbes NT, Conwell Y, Cox C. Suicide and Alzheimer's pathology in the elderly: A case–control study. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(2):137–45. | 1 |

| 33 | Takahashi Y, Hirasawa H, Koyama K, Asakawa O, Kido M, Onose H, et al. Suicide and aging in Japan: An examination of treated elderly suicide attempters. Int Psychogeriatr. 1995;7(2):239–51. | 1 |

| 34 | Tsoh J, Chiu HFK, Duberstein PR, Chan SSM, Chi I, Yip PSF, et al. Attempted suicide in elderly Chinese persons: A multi-group, controlled study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(7):562–71. | 2 |

| 35 | Waern M, Rubenowitz E, Wilhelmson K. Predictors of suicide in the old elderly. Gerontology. 2003;49(5):328–34. | 1 |

| 36 | Wijesinghe P, Gorrie C, Shankar SK, Chickabasaviah YT, Amaratunga D, Hulathduwa S, et al. Early stages of Alzheimer's disease are alarming signs in injury deaths caused by traffic accidents in elderly people (≥60 years of age): A neuropathological study. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;59(4):471–7. | 1 |

| 37 | Zucca M, Rubino E, Vacca A, Govone F, Gai A, de Martino P, et al. High Risk of Suicide in Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2018;1,533,317,518,817,609. | 2 |

Analysis of the quality of studies included in meta-analysis.

| Article | Previous sample size estimation (a) | Appropriate recruitment (a) | Appropriate group to compare (a) | Appropriate Instrum. Of measurement (a) | Evaluation (b) | Limitations (a) | Overall result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashby et al. (1991) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 0 | (+) | 3+ |

| Bellini et al. (1998) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 0 | (−) | 1+ |

| Borges et al. (2015) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 2+ |

| Chen et al. (2018) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 4+ |

| Chiu et al. (2004) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 0 | (+) | 5+ |

| Conwell et al. (2000) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 0 | (+) | 3+ |

| Draper et al. (2002) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 0 | (+) | 1+ |

| Draper et al. (2003) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 0 | (+) | 1+ |

| Eliasen et al. (2018) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 4+ |

| Erlangsen et al. (2008) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 2+ |

| Florio et al. (1997) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | 0 | (+) | 1− |

| Forsell et al. (1997) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 0 | (−) | 1− |

| Harwood et al. (2001) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 0 | (+) | 3+ |

| Heun et al. (2003) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 0 | (+) | 5+ |

| Hiroeh et al. (2001) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (−) | 4− |

| Kiosses et al. (2017) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 0 | (+) | 3+ |

| Lyness et al. (1992) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 4+ |

| Matschke et al. (2018) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 6+ |

| McCarthy et al. (2013) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 4+ |

| Morgan et al. (2018) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 4+ |

| Neufeld et al. (2015) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 0 |

| Ng et al. (2018) | 0 | 0 | (+) | (+) | (−) | 0 | 1+ |

| Nishida et al. (2015) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 2+ |

| Osvath et al. (2005) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 2+ |

| Park et al. (2011) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | 6− |

| Peisah et al. (2007) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 4+ |

| Purandare et al. (2009) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 2+ |

| Qin (2011) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 2+ |

| Randall et al. (2014) | 0 | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 3+ |

| Rao et al. (1997) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 2+ |

| Rubin y Kinscherf (1989) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | 0 |

| Rubio et al. (2001) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 0 | (+) | 3+ |

| Takahashi et al. (1995) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 2+ |

| Tsoh et al. (2005) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 0 | (+) | 3+ |

| Waern et al. (2003) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 0 | (+) | 3+ |

| Wijesinghe et al. (2017) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 0 |

| Zucca et al. (2018) | (−) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (+) | 2+ |

(a) (+)=Yes, (0)=Not indicated/not required; (−)=Not undertaken.

(b): (+)=Blind and independent, (0)=Blind or independent, (−)=None/Not specified.

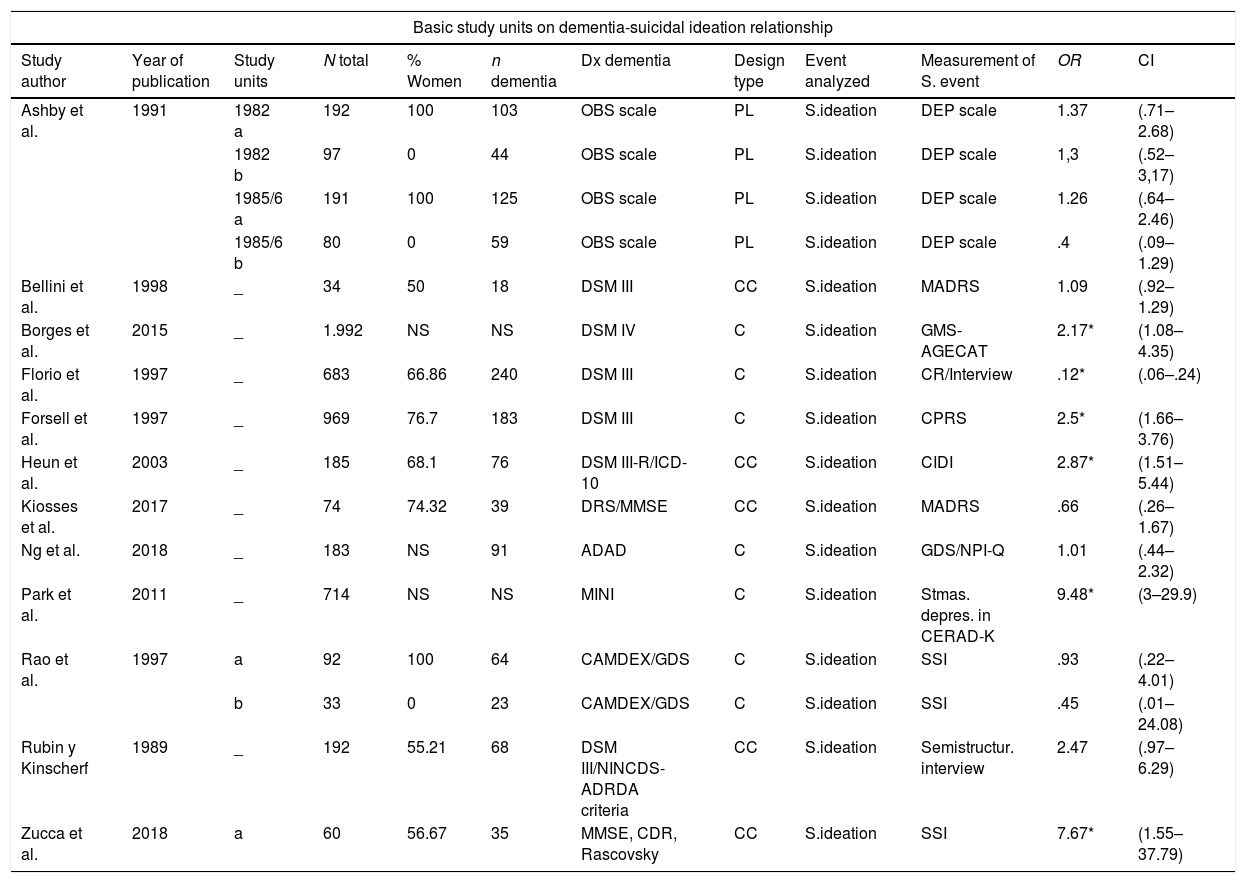

Twelve studies (from which a total of 16 BSU were obtained) analyzed the relationship between dementia and suicidal ideation (Table 3). The designs used were: 6 cross-sectional, 5 case–controls and one prospective longitudinal. Mean effect size was OR+=1.366 (95% CI: .780–2.390), indicating that, on average, the dementia groups presented with a suicidal ideation probability 1.366 times greater than the control groups, with this relationship being interpreted as low magnitude,4 although this relationship was not statistically significant, t(15)=1.186;, p=.254. Heterogeneity was observed between the studies, Q (15)=86.025; p<.0001; I=88.81%, also apparent in the forest plot (Fig. 2A). Through a funnel plot (Fig. 2B), the trim-and-fill technique and the Egger test, which did not acquire statistical significance: t(14)=−.064; p=.949, publication bias was ruled out as a threat against the validity of results obtained.

Characteristics and results from the basic study units included in the meta-analysis.

| Basic study units on dementia-suicidal ideation relationship | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study author | Year of publication | Study units | N total | % Women | n dementia | Dx dementia | Design type | Event analyzed | Measurement of S. event | OR | CI |

| Ashby et al. | 1991 | 1982 a | 192 | 100 | 103 | OBS scale | PL | S.ideation | DEP scale | 1.37 | (.71–2.68) |

| 1982 b | 97 | 0 | 44 | OBS scale | PL | S.ideation | DEP scale | 1,3 | (.52–3,17) | ||

| 1985/6 a | 191 | 100 | 125 | OBS scale | PL | S.ideation | DEP scale | 1.26 | (.64–2.46) | ||

| 1985/6 b | 80 | 0 | 59 | OBS scale | PL | S.ideation | DEP scale | .4 | (.09–1.29) | ||

| Bellini et al. | 1998 | _ | 34 | 50 | 18 | DSM III | CC | S.ideation | MADRS | 1.09 | (.92–1.29) |

| Borges et al. | 2015 | _ | 1.992 | NS | NS | DSM IV | C | S.ideation | GMS-AGECAT | 2.17* | (1.08–4.35) |

| Florio et al. | 1997 | _ | 683 | 66.86 | 240 | DSM III | C | S.ideation | CR/Interview | .12* | (.06–.24) |

| Forsell et al. | 1997 | _ | 969 | 76.7 | 183 | DSM III | C | S.ideation | CPRS | 2.5* | (1.66–3.76) |

| Heun et al. | 2003 | _ | 185 | 68.1 | 76 | DSM III-R/ICD-10 | CC | S.ideation | CIDI | 2.87* | (1.51–5.44) |

| Kiosses et al. | 2017 | _ | 74 | 74.32 | 39 | DRS/MMSE | CC | S.ideation | MADRS | .66 | (.26–1.67) |

| Ng et al. | 2018 | _ | 183 | NS | 91 | ADAD | C | S.ideation | GDS/NPI-Q | 1.01 | (.44–2.32) |

| Park et al. | 2011 | _ | 714 | NS | NS | MINI | C | S.ideation | Stmas. depres. in CERAD-K | 9.48* | (3–29.9) |

| Rao et al. | 1997 | a | 92 | 100 | 64 | CAMDEX/GDS | C | S.ideation | SSI | .93 | (.22–4.01) |

| b | 33 | 0 | 23 | CAMDEX/GDS | C | S.ideation | SSI | .45 | (.01–24.08) | ||

| Rubin y Kinscherf | 1989 | _ | 192 | 55.21 | 68 | DSM III/NINCDS-ADRDA criteria | CC | S.ideation | Semistructur. interview | 2.47 | (.97–6.29) |

| Zucca et al. | 2018 | a | 60 | 56.67 | 35 | MMSE, CDR, Rascovsky | CC | S.ideation | SSI | 7.67* | (1.55–37.79) |

| Basic study units on dementia-attempted suicide relationship | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study author | Year of publication | Study units | N total | % Women | n dementia | Dx dementia | Design type | Event analyzed | Measurement of S. event | OR | CI |

| Chen et al. | 2018 | _ | 455.630 | 47.78 | 91,126 | ICD-9 | Ch | Attempted S. | Register | .66* | (.52–.83) |

| Draper et al. | 2002 | _ | 610 | 74.6 | 361 | BEHAVE-AD/FAST | C | Attempted S. | HBS/HDRS | 8.7* | (6.49–11.66) |

| Draper et al. | 2003 | _ | 593 | 73.2 | 272 | BEHAVE-AD/FAST | C | Attempted S. | HBS/HDRS | 1.89* | (1.43–2.48) |

| Eliasen et al. | 2018 | _ | 98.714 | 63 | 90 | ICD-10 | CC | Attempted S. | Register | 4.77* | (3.06–7.42) |

| Lyness et al. | 1992 | _ | 167 | 73.6 | 14 | DSM III | C | Attempted S. | Register (RRR) | .17 | (.01–3.01) |

| Morgan et al. | 2018 | _ | 51.375 | 59.6 | 2301 | ICD-10 | Ch | Attempted S. | Register | 2.64* | (2.3–3.03) |

| Neufeld et al. | 2015 | _ | 204.797 | 64.1 | 31,682 | Register (CPS) | C | Attempted S. | Register (ISH) | 1.43* | (1.28–1.59) |

| Osvath et al. | 2005 | _ | 214 | 70.09 | 124 | DSM IV/MMSE | CC | Attempted S. | Structured interview | .27* | (.14–.5) |

| Randall et al. | 2014 | a | 34.564 | 62.9 | 933 | Register (MRHA) | CC | Attempted S. | Register | 8.38* | (7.25–9.69) |

| Takahashi et al. | 1995 | _ | 100 | 60 | 18 | DSM III-R | CC | Attempted S. | Clinical interview | 1.73 | (.61–4.91) |

| Tsoh et al. | 2005 | a | 157 | 60.5 | 14 | DSM III-R | CC | Attempted S. | Register/SCID | 9.89* | (2.13–45.88) |

| Zucca et al. | 2018 | b | 60 | 56.67 | 35 | MMSE, CDR, Rascovsky | CC | Attempted S. | SSI | 7.29 | (.37–141.74) |

| Basic study units on dementia-completed suicide relationship | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study author | Year of publication | Study units | N total | % Women | n dementia | Dx dementia | Design type | Event analyzed | Measurement of S. event | OR | CI |

| Chiu et al. | 2004 | _ | 170 | 55.9 | 4 | PA (DSM III-R) | CC | Completed S. | Register | 1.44 | (.2–10.48) |

| Conwell et al. | 2000 | _ | 238 | 54.6 | 10 | PA (DSM III-R) | CC | Completed S. | Register | .53 | (.06–4.31) |

| Erlangsen et al. | 2008 | a | 10,103,643(z) | 100 | 52,513(z) | Register (ICD) | PL | Completed S. | Register | 5.14* | (3.94–6.71) |

| b | 8,545,231(z) | 0 | 34,888(z) | Register (ICD) | PL | Completed S. | Register | 5.62* | (4.5–7.02) | ||

| Harwood et al. | 2001 | _ | 108 | 63.89 | 15 | PA (ICD-10) | CC | Completed S. | Register | .2* | (.05–.78) |

| Hiroeh et al. | 2001 | a | 2,332,584 | 100 | 50,767 | Register (ICD-8) | C | Completed S. | Register | .56* | (.44–.7) |

| b | 4,787,163 | 0 | 36,271 | Register (ICD-8) | C | Completed S. | Register | 1.74* | (1.41–2.13) | ||

| Matschke et al. | 2018 | _ | 324 | 33.33 | 16 | PA | CC | Completed S. | Register | 1 | (.37–2.73) |

| McCarthy et al. | 2013 | _ | 180.876 | 3.1 | 85,990 | Register (MDS) | C | Completed S. | Register | .63 | (.38–1.04) |

| Nishida et al. | 2015 | _ | 24 | 41.7 | 1 | PA (CDR) | C | Completed S. | Register | 3.86 | (.14–104.65) |

| Peisah et al. | 2006 | _ | 161 | 30.69 | 42 | PA (ICD-10/DSM-IV/NIA-Reagan criteria) | CC | Completed S. | Register | .8 | (.39–1.65) |

| Purandare et al. | 2009 | _ | 590 | 47 | 118 | PA (ICD-10) | CC | Completed S. | Register | .34* | (.2–.61) |

| Qin | 2011 | a | 157,245 | 100 | 410 | Register (ICD 8 y 10) | CC | Completed S. | Register | 3.93* | (3.024–5.11) |

| b | 287,052 | 0 | 649 | Register (ICD 8 y 10) | CC | Completed S. | Register | 3.53* | (2.84–4.38) | ||

| Randall et al. | 2014 | b | 8400 | 25.85 | 288 | Register (MRHA) | CC | Completed S. | Register | 4.1* | (3.23–5.2) |

| Rubio et al. | 2001 | _ | 84 | 39.3 | 10 | PA (DSM III) | CC | Completed S. | Register | .84 | (.2–3.53) |

| Tsoh et al. | 2005 | b | 158 | 55.66 | 3 | PA (DSM III-R) | CC | Completed S. | Register/Informant | .67 | (.06–7.59) |

| Waern et al. | 2003 | _ | 238 | 45.9 | 17 | PA (DSM IV) | CC | Completed S. | Register/Informant | .36 | (.1–1.3) |

| Wijesinghe et al. | 2017 | _ | 18 | 44.44 | 5 | Autopsia cerebro | CC | Completed S. | Register | .56 | (.05–6.77) |

ADAD: Autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease mutation; PA: Psychological autopsy; BEHAVE-AD: Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease Rating Scale; CAMDEX: Cambridge Examination for Mental Disorders of the Elderly; CDR: Clinical Dementia Rating Scale; CERAD-K: Development of the Korean version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Packet; CIDI: Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CPRS: Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale; CPS: Cognitive Performance Scale; DEP: Depression scale; DRS: Dementia Rating Scale; DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; Dx: Diagnostic method; FAST: Functional Assessment Staging; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; GMS-AGECAT: Geriatric mental scale-automated geriatric examination for computed assisted taxonomy; HBS: Harmful Behaviors Scale; CR: Clinical record; HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; CI: 95% Confidence Interval; ICD: International Classification of Diseases; ISH: Intentional self-harm; MADRS: Montgomery-Asberg depression scale; MDS: Minimum Data Set; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; MRHA: Manitoba Regional Health Authority; N: sample size; n: subsample size; NIA: National Institute on Aging-Reagan Institute; NINCDS-ADRDA: National Institute of Neurologic, Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association; OBS scale: Organic Brain Syndrome scale; RRR: Risk-Rescue Rating; OR: odds ratio; S: Suicide; SCID: Structured Clinical Interviewfor DSM; SSI: Scale for Suicidal Ideation.

Designs: CC: Case–control/PL: Prospective longitudinal/C: Cross-sectional; NS: Not specified.

(z): People/year.

*p<.05.

With regard to the variables relating to the sample characteristics under study, the mean age of the subjects diagnosed with dementia presented a statistically significant association with the OR and a very high percentage of explained variance, bj=−.046; F(1, 2)=22.453; p=.040; k=4; R2=.99, so that the lower the age of the subjects diagnosed the greater the probability of experiencing the suicidal ideation event (supplementary information (SI)Table A1, inAppendix A additional material appendix). However, this result should be treated cautiously, since it may be highly unstable due to the low study number. Notwithstanding, the type of method used to carry out the dementia diagnosis was marginally significant, F(2, 13)=3.749; p=.052, with a percentage of explained variance of moderate magnitude, R2=24%. It may therefore be stated that the type of method used to diagnose dementia presented with a relationship with effect size, with this being greater when clinical diagnosis was used (OR+=4.945; k=3), followed by the “mixed” category (OR+=1.117; k=6) and finally by the use of scales or tests (OR+=.933; k=7) (IS Table A2 inAppendix A additional material appendix).

Analysis on the dementia-attempted suicide relationshipIn 11 studies (12 BSU) there was a relationship between dementia and attempted suicide (Table 3). The designs used were as follows: 5 case–control, 4 cross-sectional, and 2 cohorts. The mean effect size was OR+=2.239 (95% CI: 1.009–4.966), indicating that, on average, in the groups with dementia the probability of suicide attempts was 2.239 times higher than in the control groups, and this relationship could be interpreted as medium magnitude.34 Said relationship was statistically significant, t(11)=2.227; p=.048. Raised heterogeneity was observed in the studies, Q(11)=635.114; p<.0001; I2=98.81%, and also apparent in the forest plot (Fig. 2C). Through a funnel plot (Fig. 2D), the trim-and-fill technique and the Egger test, t(10)=−.298; p=.772, publication bias was ruled out as a threat against the validity of meta-analysis results obtained.

Moderating variables analysisResults showed that none of the moderating variables analyzed were statistically related to the effect size (IS Tables A4, A5 and A6 inAppendix A additional material appendix).

Analysis dementia-completed suicide relationshipThe relationship between dementia and completed suicide (Table 3) was analyzed in 16 studies (19 BSU). The designs used were: 12 case–control, 3 cross-sectional and one prospective longitudinal. Mean effect size was OR+=1.285 (95% CI: .771–2.140), indicating that in the group with dementia there was a 1.285 times greater probability of completing suicide than in the control group, with this relationship being interpreted as low magnitude,34 although it was not statistically significant, t(18)=1.031; p=.316. Notable heterogeneity was observed in the studies: Q(18)=410.484; p<.0001; I2=96.30%, also apparent in the forest plot (Fig. 2E). Through the funnel plot (Fig. 2F), the trim-and-fill technique and the Egger test, t(17)=−1.894; p=.075, publication bias was ruled out as a threat against the validity of meta-analysis results obtained.

Moderating variables analysisOf the variables relating to the characteristics of the subjects under study, the type of sample reached a statistically significant result, F(2. 16)=4.842; p=.023, with a percentage explained variance of 35% (R2=.35), with the mean effect in the community sample being higher (OR+=5.379; k=2), followed by the mixed sample (OR+=1.635; k=6),and finally by that obtained using the autopsy register (OR+=.866; k=11) (IS Table A8 inAppendix A additional material appendix).

With regard to the methodological type moderating variables, the form of measuring completed suicide showed a statistically significant relationship with the effect size, F(1, 17)=4.480; p=.049; R2=.20, with effect size being higher when registers were used (OR+=1.656; k=14) (IS Table A8 inAppendix A additional material appendix). Another statistically significant moderating variable was the measurement of the effect size used, F(1, 17)=4.812; p=.042; R2=.22, with greater effect being reached when the measurement was indirect (OR+=1.601; k=16) than when it was direct (OR+=.397; k=3) (IS Table A8 inAppendix A additional material appendix). Lastly, the study design presented a marginally significant result, F(2, 16)=3.585; p=.052, with a percentage of explained variance of 23%. Specifically, the effect found was greater when the study design was prospective longitudinal (OR+=5.378; k=2), followed by cases and controls (OR+=1.078; k=13), then lastly by studies with a cross-sectional study design (OR+=.947; k=4) (ISTable A8 inAppendix A additional material appendix).

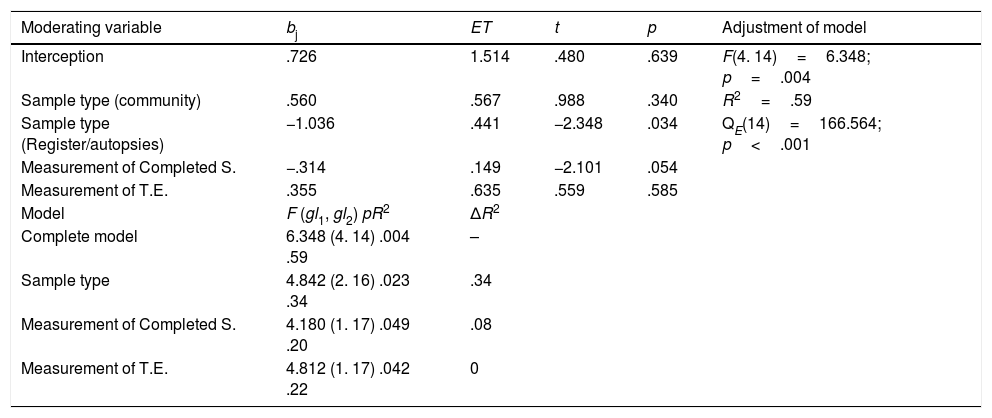

Predictive modelTo propose a subset of study characteristics able to explain a good part of the variability of the relationship found between dementia and completed suicide, the multiple meta-regression model was applied. The moderating variables included were: (a) the type of sample: community (2 studies), register of autopsies (11 studies) and mixed (6 studies); (b) measurement of completed suicide: registers (14 studies) and mixed (5 studies); and measurement of effect size: direct (3 studies) and indirect (16 studies). Due to the moderating “sample type” variable being formed by 3 categories, 2 predictors were generated using a fictitious code.

On application of simple meta-regressions, the “sample type” variables, “measurement of completed suicide” and “measurement of effect size” had statistically significant results (p=.023; p=.049 and p=0.042, respectively (see Table 4).

Results of the multiple meta-regression mixed effects model.

| Moderating variable | bj | ET | t | p | Adjustment of model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interception | .726 | 1.514 | .480 | .639 | F(4. 14)=6.348; p=.004 |

| Sample type (community) | .560 | .567 | .988 | .340 | R2=.59 |

| Sample type (Register/autopsies) | −1.036 | .441 | −2.348 | .034 | QE(14)=166.564; p<.001 |

| Measurement of Completed S. | −.314 | .149 | −2.101 | .054 | |

| Measurement of T.E. | .355 | .635 | .559 | .585 | |

| Model | F (gl1, gl2) pR2 | ΔR2 | |||

| Complete model | 6.348 (4. 14) .004 .59 | – | |||

| Sample type | 4.842 (2. 16) .023 .34 | .34 | |||

| Measurement of Completed S. | 4.180 (1. 17) .049 .20 | .08 | |||

| Measurement of T.E. | 4.812 (1. 17) .042 .22 | 0 |

bj: Partial regression coefficient; SE: Standard statistical error t; F: Overall statistical adjustment of the model; p: Level of probability of each contrast statistic; gl1, gl2: Degrees of freedom associated with the statistic F; QE: Contrast statistic of model specification; R2: Proportion of explained variance; t: Contrast statistic of the significance of each predictor. ΔR2: Increase in R2 because of including the predictor in the model once the other predictors have already been introduced.

When these 3 variables were introduced into the meta-regression model, the complete model was statistically significant, F(4, 14)=6.348; p=.004, with a 59% explained variance. The model did not reach a suitable specification level, QE(14)=166.564; p<.001, which indicated the existence of other moderating variables that could have influenced the relationship between dementia and completed suicide. Of the 4 predictors included in the model, only the “type of autopsy register sample” presented a statistically significant relationship with effect size (p=.034), once the sway of the other predictors had been biased.

Table 4 also shows the increase in the proportion of explained variance by each moderating variable included in the model once the other variable had already been introduced. The increase in R2 when the “sample type” variable was included in the model was 34%, whilst the “measurement of completed suicide” variables and the “measurement of effect size” variables provided an increase of 8% and 0%, respectively.

DiscussionThe results obtained from this meta-analysis show that people with dementia are at greater risk of experiencing suicidal events, and particularly attempted suicides. These results are consistent with the description made by other authors on the possible association of suicidal events with life threatening situations, such as dementia (Draper 2015 and Serafini et al. 2016).35,36 The increase in dementia cases with advancing age13,14 could account for the higher risk (1.5 times) of committing suicide described for people over 65 years of age, with an even higher risk from 85 years upwards, compared with younger people.37

In the analysis of moderating variables which could impact the appearance of a suicide event in people with dementia, a higher effect size was found in middle age and community sample variables. People diagnosed with dementia who were younger presented with a greater probability of having experienced suicidal ideation. These results were in keeping with other previous studies.16,35,38–42 The initial stages of dementia would be a higher risk period as the person would perceive of higher threat to their life, with progressive physical and cognitive impairment, increasingly higher levels of dependence and concern on becoming a burden for their family, both emotionally and financially,39 whilst at the same time preserving certain intellectual and volitive capacities they would need for the planning and carrying out of suicidal events.

Furthermore, in the case of the community sample a positive correlation was found between dementia and completed suicide. Regarding the sample obtained from the autopsy register, the correlation was negative. We could interpret that in dementia, especially in early phases, where information from the person, family members and their environment is needed to confirm the diagnosis, which would otherwise go undetected, there is an increase in suicidal events. Also, this would be supported by other events found in the study, such as the association with a younger aged diagnosed subjects and a higher association found in the case of the longitudinal study used, which led to the initial detection and evolution of dementia symptoms. In the case of autopsy registers and findings, where data collection was more timely and limited, cases were more associated with advanced stages of dementia, since detection and collection of early symptoms did not apply. This would concur with the fact that advanced dementias could present with a certain protective effect from suicidal events.

Suicidal behavior may be considered the tip of the iceberg, the final result of interaction between many different factor described in the literature and related to elderly people, and which may become particularly exacerbated in the case of dementia.10,43 These may include religious factors,44 cultural, ethnic and immigration factors4,5–47 as well as financial factors.48,49 These factors could explain the differences found between the different countries in relation to suicide rates in general.9 Two systematic reviews have recently been published on qualitative studies focused on self-harming in older adults where risk factors such as the sensation of the loss of control, loneliness, isolation, feeling a burden or suffering from impairment in functional capacity stand out as the most relevant factors.50,51

Among the strengths of this study the following are outstanding: (i) low probability of having passed over relevant studies, due to the exhaustive search of articles relating to the study theme in 5 different databases with no restrictions placed on them, to increase their power, plus subsequent manual review of the bibliography of articles included and contact with the authors; (ii) independent review in both study screening and coding; (iii) design and review of a coding manual and an ad hoc quality scale for objective and meticulous analysis of the articles and (iv) removal of publication bias as a threat to meta-analysis results.

The limitations of this study may be grouped together into those included in the level of studies and those of review itself. The following may be emphasized for the former: (i) the majority of studies are of cross-sectional or case–control design, which limits the possibility of causal links between findings; (ii) great variability in aspects such as: mode of sample obtainment, form of dementia diagnosis, subtype analysis and/or evolutionary stage, comorbidity report, psychosocial variables analyzed, assessment of suicide event (measurement, data source and type of register). The main limitations for review itself included: (i) some studies did not present with sufficient data to be included in the statistical analysis; (ii) the low number of studies finally included in the meta-analysis advised cautious interpretation of the results obtained; (iii) impossibility of analysing the impact of psychosocial factors, due to the fact that many included studies were not examined and in those that were, the items considered were highly variable between the different studies.

ConclusionsDementia, particularly in its early stages, constitutes a risk situation for the appearance and development of suicidal events. We would recommend paying greater attention and care to those people with recent diagnoses of dementia and providing them with suitable suicide risk assessment. In future research studies we would advise assessing the interrelationship between dementia, age at diagnosis, medical comorbidities and the impact of psychosocial variables, with the appearance of the suicide phenomenon in its diverse entities, preferably in longitudinal studies.

Conflict of interestsThis study did not receive any specific grants from public sector agencies, commercial sector agencies or not-for-profit entities.

Regarding the authors who participated in the study, Dr. Navarro-Mateu reported non-financial support from Otsuka outside the presented study, and the other authors did not report any other conflicts of interests.

Please cite this article as: Álvarez Muñoz FJ, Rubio-Aparicio M, Gurillo Muñoz P, García Herrero AM, Sánchez-Meca J, Navarro-Mateu F. Suicidio y demencia: revisión sistemática y metaanálisis. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2020;13:213–227.