The aim of the present work is to determine the association between unemployment and suicide, and to investigate whether this association is affected by changes in the economic cycle or other variables such as age and sex.

MethodsA time-trend analysis was conducted to study changes in the number of suicides between 1999 and 2013 in Spain. Pearson's correlation coefficients and regression models were used to find the association between unemployment and suicide.

ResultsA significant positive association was found between unemployment and suicide in the pre-crisis period in men. In that period (1999–2007), each 1% annual increase in unemployment was associated with a 6.90% increase in the annual variation of suicide in the total population, and with a 9.04% increase in the annual variation of suicide in working age men.

ConclusionsThe correlation between unemployment and suicide is significant in periods of economic stability, but has weakened during the recent financial crisis. Unemployment and suicide have a complex relationship modulated by age, sex and economic cycle.

El objetivo del presente estudio es determinar la asociación entre desempleo y suicidio e investigar si existen factores relacionados con el ciclo económico o sociodemográficos que influyan sobre la citada asociación.

MétodosRealizamos un análisis de tendencias temporales para estudiar los cambios habidos en España en el número de suicidios entre 1999 y 2013. Utilizamos el coeficiente de correlación de Pearson y modelos de regresión para valorar la asociación entre desempleo y suicidio.

ResultadosEncontramos una asociación positiva entre desempleo y suicidio en el periodo previo a la crisis en hombres. En ese periodo (1999-2007), en la población total, cada incremento del 1% en la variación anual de desempleo se asoció a un 6,90% de incremento en la variación anual de suicidio. En hombres en edad laboral, el 1% de variación anual de desempleo se asoció a un 9,04% de incremento en la variación anual de suicidio.

ConclusionesLa correlación entre desempleo y suicidio es relevante en periodos de estabilidad económica, y más débil durante la reciente crisis económica. Desempleo y suicidio tienen una relación compleja, modulada por la edad, el sexo y el ciclo económico.

Suicidal behaviour is influenced by personal (micro-socioeconomic level) and social (macro-socioeconomic level) factors.1 Among the latter, financial/economic crisis and its consequences (unemployment, low income, personal debt, mortgage foreclosures) have often been associated with increases in suicide rates.2–7 However, evidence regarding the influence of changes in the economic cycle on mental health remains ambiguous8,9 and is sometimes challenged.10–13 In particular, the association between one aspect of the financial crisis, i.e. unemployment, and suicide is weak,14 and its amplitude varies from country to country. Furthermore, the relationship is influenced by other variables such as gender, age, labour market opportunities, duration of unemployment, and level of job skills; and we know that the hypothetical effect (increase in suicide rates) and cause (increased unemployment) could not be simultaneous.15–19 Moreover, suicide data must be interpreted cautiously because the accuracy of the national suicide databases is unclear.20

Spain has been particularly hard hit by the financial crisis. Following a decade of expansion, economic growth began to slow in 2007, and gross domestic product (GDP) began to contract as of the second quarter of 2008, ushering in a recession lasting seven successive quarters.7,21,22 Since 2007, the downturn in the Spanish economy has caused job losses, home foreclosures, and a large national budget deficit.23 Between 2007 and 2014, unemployment trebled from 8.60% to 26.94% (first quarter of 2013), reaching the highest rate in the European Union. Since the onset of the financial crisis, austerity measures have included salary reductions for health care personnel, changes in drug-prescribing policies, and delays in payments to suppliers.24

This study aims firstly to determine the association between unemployment and suicide in Spain between 1999 and 2014 and secondly to investigate whether this association is affected by characteristics of the population or changes in the economic cycle.

MethodAnnual data for the number of deaths by suicide were obtained from the database of the National Statistics Institute (INE) of Spain. The annual unemployment data were obtained from the database of the National Employment Institute. All deaths by suicide between 1999 and 2014 in Spain were selected. Data from 17 Autonomous Communities of Spain were analysed, including the Autonomous Cities of Ceuta and Melilla. Suicides deaths are coded as X60-X84 (ICD-10).25 In Spain, suicides are determined by a judicial inquest, as is any death that may have a possible accidental or violent cause.

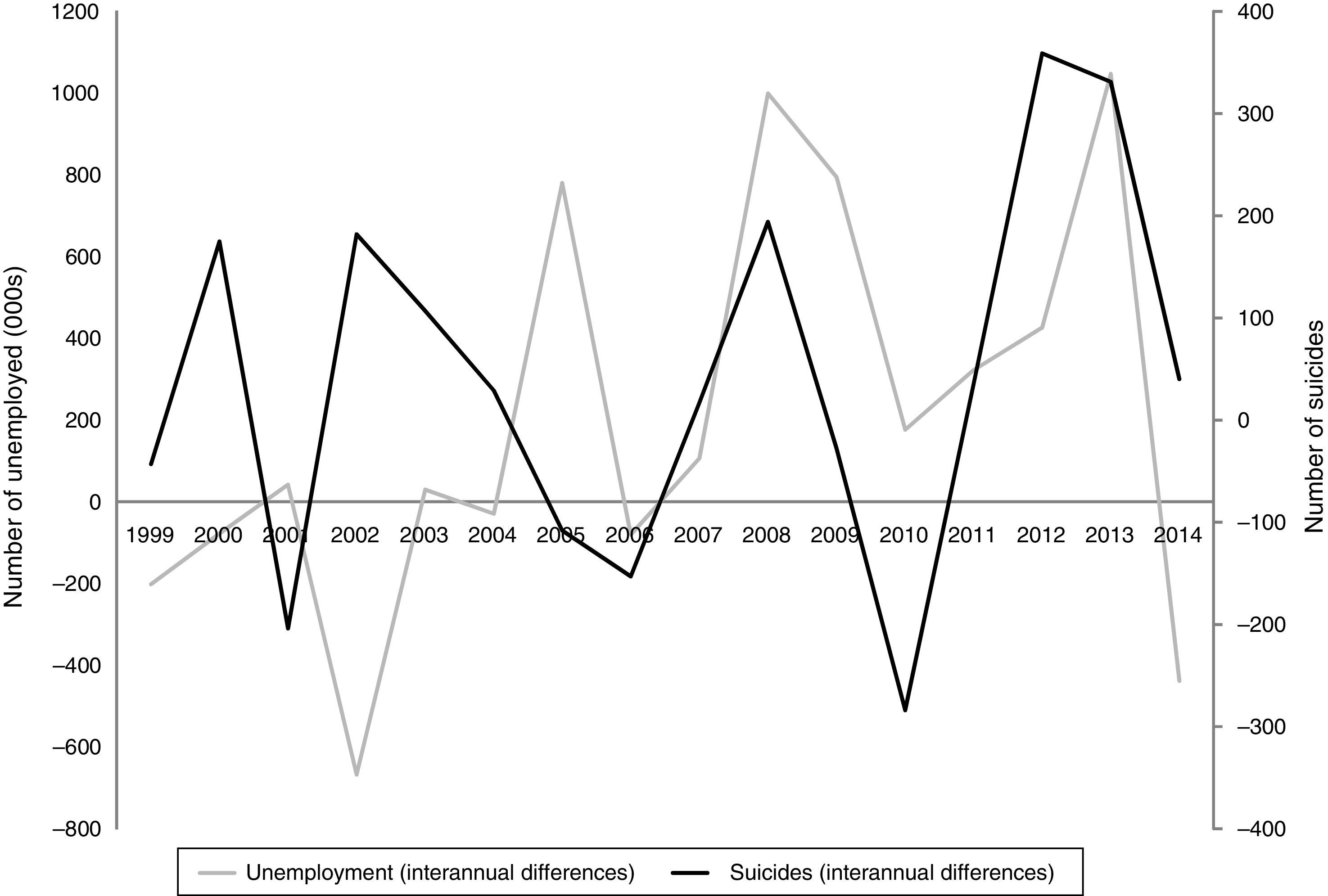

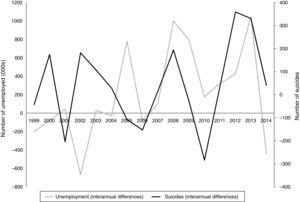

To estimate the number of suicides that may be attributed to an increase in unemployment, instead of studying the overall unemployment numbers (a combination of the long-term unemployed and those who have lost their jobs more recently), we assessed annual variations in unemployment (AVU) figures, which more accurately reflect the number of jobs lost each year, and correlated these figures with the annual variation in the number of suicides (AVS).

Statistical analysisData normality was checked by means of the Anderson–Darling test.26 A time-trend analysis was conducted using the Cox–Stuart test27 to determine the change in the number of suicides in the total population, in men and in women. Two types of linear regression models were then fitted to find the association between changes in unemployment levels and suicide. The first model made it possible to calculate the AVS rates as a function of the AVU rates, while the second consisted of disaggregated linear regression models for the total population of men and women, giving us information about differences in the relationship between unemployment and suicide rates before and during the crisis. Finally the study was repeated following the same pattern but using only information for men and women 20–64 years of age (working age group).

All mathematical and statistical calculations were performed in the R software28 environment for statistical computing and graphics.

ResultsThe Anderson–Darling test suggests that the number of suicide cases follows a normal distribution in the years of interest in the general population (p=0.188), men (p=0.310) and women (p=0.248), likewise in the case of the subset of suicides between 20 and 64 years of age (general population p=0.086, men p=0.460, and women p=0.089). It allows the use of an analysis of variance to compare the differences between the average number of suicides in the years before and during the economic downturn. Similar results were obtained when the normality of the number of unemployed people in the years of interest was analysed for the general population (p=0.565), men (p=0.564), and women (p=0.113).

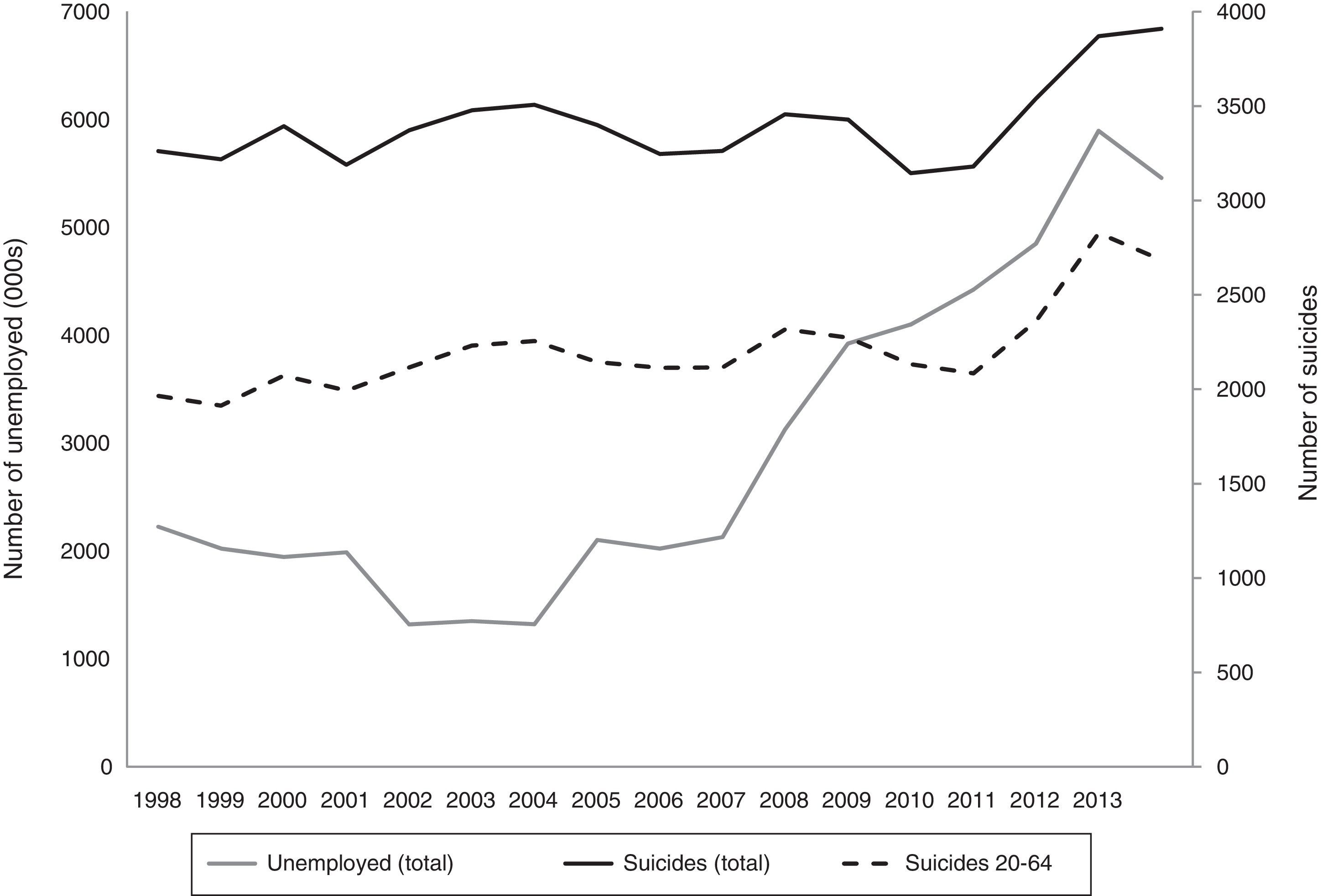

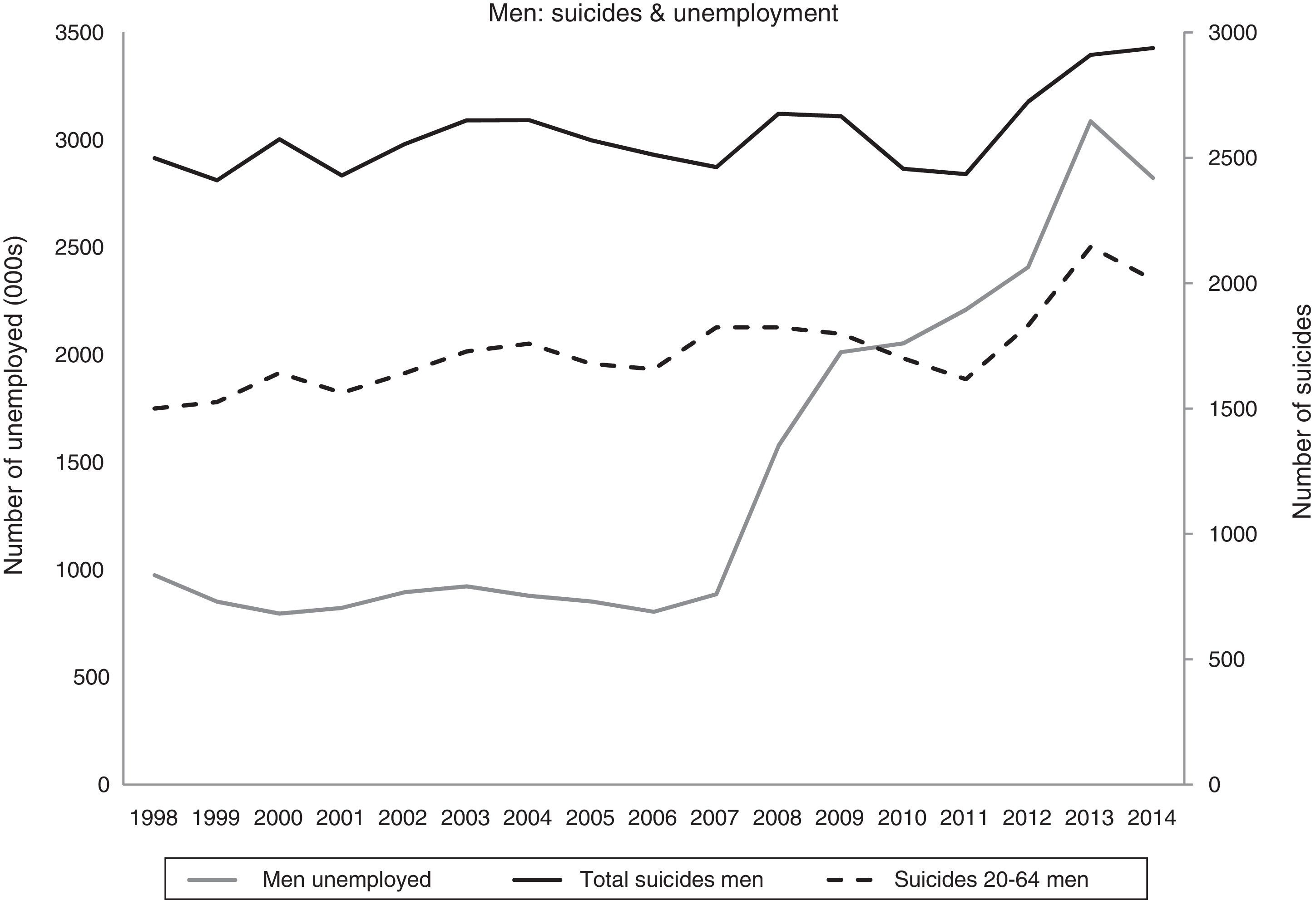

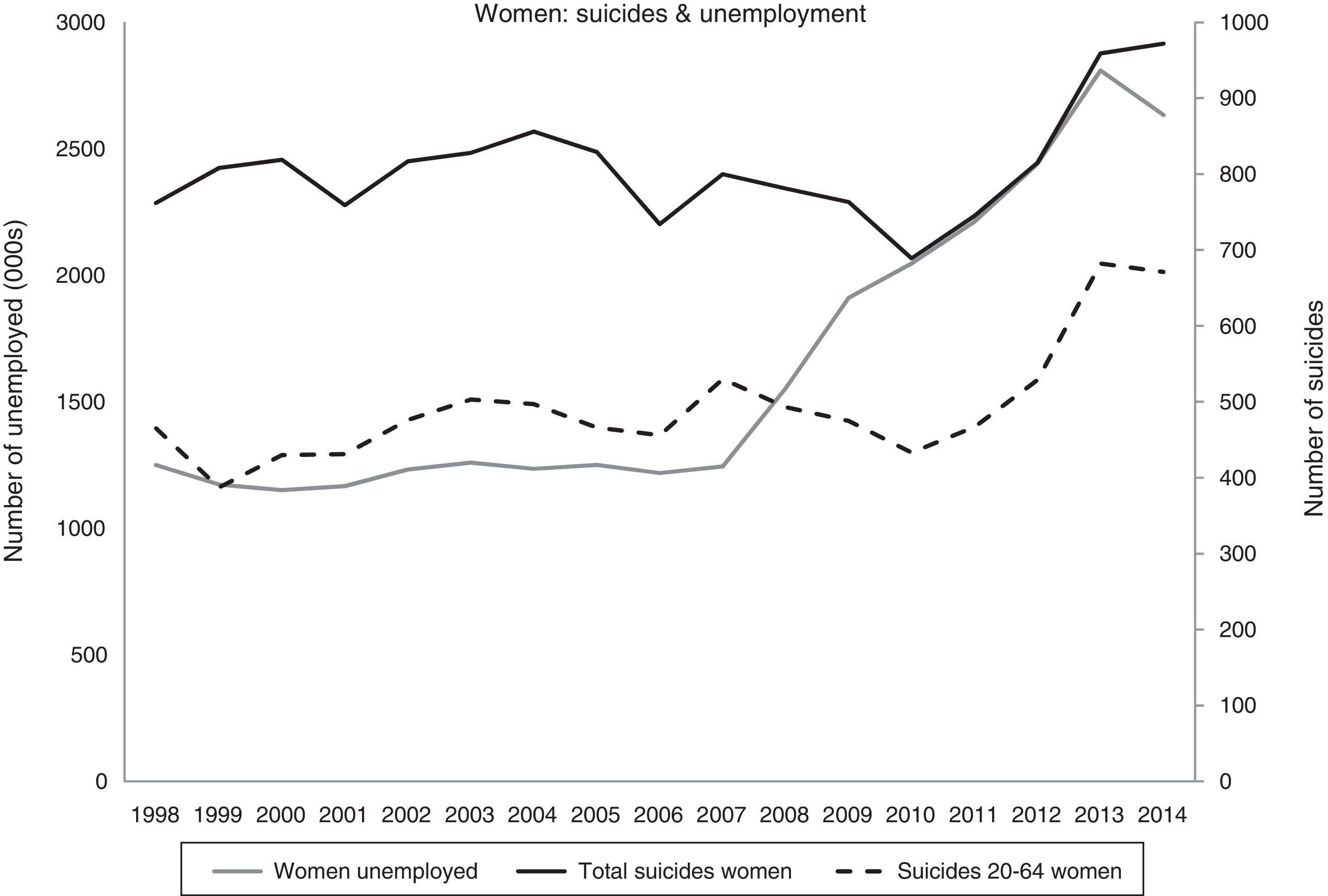

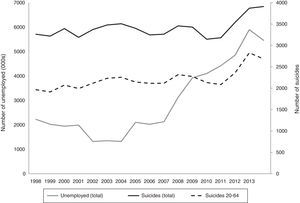

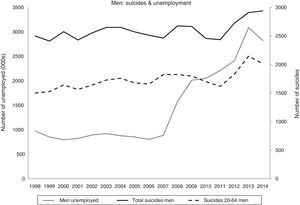

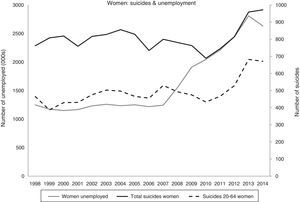

Figs. 1–4 show the changes in the numbers of suicides and unemployed people in Spain during the period 1999–2014, for the overall population (Fig. 1) and disaggregated for males (Fig. 2) and females (Fig. 3). We can see a clear increase in the number of unemployed from 2007 onwards, and an increase in the number of suicides of both sexes beginning with a delay of three years in women and four years in men.

According to the results of the Cox–Stuart tests, before the start of the economic crisis in 2008, the number of suicides was stable without any upward or downward trend in the overall population (p=0.0625), men (p=0.3125), or women (p=0.3125). In the total analysis for the entire period (1999–2014), we found similar results, i.e. there were no significant trends in the total population (p=0.1445), men (p=0.1445), or women (p=0.3633). Nor were there significant differences between the numbers of suicides in the years before the crisis (1999–2007) and the subsequent period (2008–2014).

To determine the possible influence of the business cycle on the association between unemployment and suicide, we separately studied the period of years prior to the start of the crisis (1998–2007) and the years during the crisis (2008–2014). The average AVU in Spain between 2008 and 2014 was 4.85% and the average AVS in the same period was 2.83%.

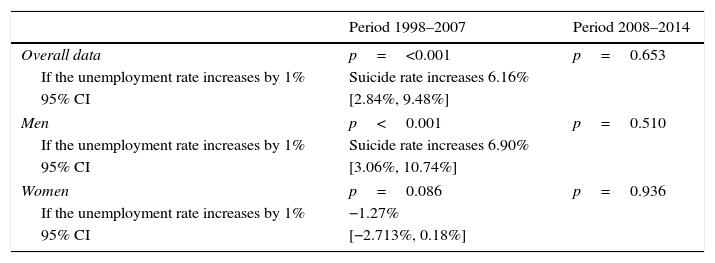

The results obtained are shown in Table 1 and they confirm the existence of a significant association between AVU and AVS, but only in the period before the economic crisis (1998–2007). In the period between 1998 and 2007, on analysing the total population, we found that each annual 1% increase in the unemployment rate was associated with a 6.16% increase in the suicide rate (95% CI 2.84–9.48%; p=<0.001). A disaggregated analysis shows a positive correlation in men and a negative one in women.

Annual variation of unemployment and suicide. Disaggregated linear regression models for total population, men, and women.

| Period 1998–2007 | Period 2008–2014 | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall data | p=<0.001 | p=0.653 |

| If the unemployment rate increases by 1% | Suicide rate increases 6.16% | |

| 95% CI | [2.84%, 9.48%] | |

| Men | p<0.001 | p=0.510 |

| If the unemployment rate increases by 1% | Suicide rate increases 6.90% | |

| 95% CI | [3.06%, 10.74%] | |

| Women | p=0.086 | p=0.936 |

| If the unemployment rate increases by 1% | −1.27% | |

| 95% CI | [−2.713%, 0.18%] | |

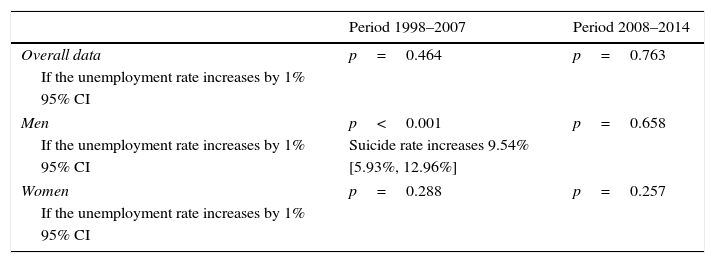

For working age people (Table 2), we can see that before the crisis there is a positive association between the increase in suicide and unemployment in men only, but we did not find a significant correlation during the crisis period. In working age men, in the pre-crisis period, each annual 1% increase in the unemployment rate was associated with a 9.54% increase in the suicide rate (95% CI 5.93–12.96%; p=<0.001).

Annual variation of unemployment and suicide. Disaggregated linear regression models for total population, men, and women ages 20–64.

| Period 1998–2007 | Period 2008–2014 | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall data | p=0.464 | p=0.763 |

| If the unemployment rate increases by 1% | ||

| 95% CI | ||

| Men | p<0.001 | p=0.658 |

| If the unemployment rate increases by 1% | Suicide rate increases 9.54% | |

| 95% CI | [5.93%, 12.96%] | |

| Women | p=0.288 | p=0.257 |

| If the unemployment rate increases by 1% | ||

| 95% CI | ||

In the study of the relationship between unemployment and suicide in Spain, we found variations in the results depending on the characteristics of the analysis. First, in the time period analysed (1999–2014), there was a sharp increase in unemployment beginning in 2007 and a non-significant increase in suicide rates in the last years of the period. Secondly, analysing the correlation between AVU and AVS, we observed a significant association between suicide that varies in intensity and even in sign depending on variables such as sex, age, and economic cycle. The correlation is positive in men in the pre-crisis period and is even stronger in working age men. Particularly striking is the lack of correlation between suicide and unemployment during the crisis in any age or sex group. This could be due to an asynchrony effect of the crisis. The economic downturn would produce an immediate, sharp rise in unemployment, while its effect on suicide would be delayed for years.29

It is difficult to compare our data with the data from different studies because of differences in methodology and other aspects such as the geographical variability in suicide.30,31 Characteristics of the population (social support or family structure) may explain differences between countries, but the use of certain data (total suicide rates) could also obscure the magnitude of a specific association, i.e. rise in suicide rates in working age men, as they seem to be more directly affected by the financial crisis.2,32

An ecological study that analysed Spanish data on suicide between 1981 and 2008 using a Bayesian Lee-Carter model31 showed an increase in suicide mortality in 2007and 2008, which was blamed on the economic crisis. Another study of Spanish suicide data between 2005 and 2010 showed an 8% increase in the suicide rate above the underlying trends since the financial crisis, concluding that the financial crisis in Spain has been associated with a relative increase in suicides, with males and those of working age at particular risk.7 That study has differences with ours both in time series and in methodology (segmented regression with a seasonally adjusted quasi-Poisson model). Furthermore, it is questionable whether the financial crisis should be considered an abrupt event for purposes of determining the time of onset of the crisis and concerning the study of the association between unemployment and suicide.33

The relationship between unemployment and suicide has been evidenced in several other recent studies, both in analysing pooled data from the European Union (EU) and analysing the situation of individual countries (UK, USA). One European study fitted with a multivariate regression, correcting for population ageing, past mortality, and employment trends, and country-specific differences in health-care infrastructure, found that a one percentage point rise in unemployment was associated with a rise in the suicide rate of 0.79% (95% CI 0.16–1.42; p=0.016).34 Another European study covering the period between 2000 and 2010 found that unemployment and suicide rates are globally statistically associated in several western European countries; however, it found a weaker association and a variable sensitivity to the ‘crisis effect’ among countries. The authors conclude that this inconsistency provides arguments against its causal interpretation.14 The last European study employing a panel dataset of 245 regions in 29 countries over the period 1999–2010 shows that unemployment does have a significantly positive influence on suicides, and that influence varies among gender and age groups, males of working age being particularly sensitive.35 The UK study performed a time-trend analysis and reached two major conclusions: first that between 2008 and 2010 about 1000 excess suicides (846 among men and 155 among women) were associated with the economic recession and secondly that each 10% increase in the number of unemployed men was associated with a 1.4% (0.5–2.3%) increase in male suicides.2 The US study using time-trend regression models to assess excess suicides occurring during the economic crisis found that a one percentage point rise in unemployment was associated with a 0.99% increase in the suicide rate (95% CI 0.60–1.38; p<0.0001), which is closer to the association estimated when there was no labour market protection (1.06%).36 Our data confirm the association between suicide and unemployment, highlighting the importance of considering annual variations and variables such as gender and age and economic cycle. The relationship between unemployment and suicide is a complex one and the economic cycle and sociodemographic variables could act as modulators.

Previous data show that the impact of unemployment on suicide is strongly affected by the level of unemployment protection37 so that some countries have been able to avoid increasing suicides rates during economic downturns.11,38,39 This highlights the need to implement social policies to prevent deaths by suicide in vulnerable populations in periods of rising unemployment.36,39–41 Reducing suicide rates or at least preventing their rise are challenges not only for mental health professionals but for society as a whole.9 Future research should explore other risk factors including personal and economic (foreclosures, financial losses) factors and access to means of self-harm36,42 as well as possible delayed effects of economic changes on suicide.29

Our findings have some limitations. The analysis of our data did not take into account the employment status of suicide victims, so we cannot study the potential differences between employed and unemployed groups. We measured unemployment based on the number of claimants, which may differ from the true number of unemployed. The unemployment rate is not disaggregated by sex, so the overall unemployment rate explains the suicides of both men and women. Data about suicides should be interpreted with caution because of the difficulties in registration and classification. In Spain there are significant discrepancies as the official suicide figures provided by the National Institute of Statistics are lower than those obtained directly from those who conduct autopsies of suicides, medical examiners at the Institute of Legal Medicine. It should also be considered that the overall Spanish results are not valid for each of the autonomous communities, as variations have been detected in changes in suicide rates among the different regions. Finally in 2014 the crisis was still ongoing in Spain, so any conclusions may be premature.

ConclusionsThe correlation between unemployment and suicide is strong in periods of economic stability, but has weakened during the recent financial crisis; and unemployment and suicide have a complex relationship modulated by age, sex and economic cycle.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments on human beings or on animals have been performed for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Iglesias-García C, Sáiz PA, Burón P, Sánchez-Lasheras F, Jiménez-Treviño L, Fernández-Artamendi S, et al. Suicidio, desempleo y recesión económica en España. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2017;10:70–77