Patients with schizophrenia sometimes internalise social stigma associated to mental illness, and they develop personal stigma. Personal stigma includes self-stigma (internalisation of negative stereotypes), perceived stigma (perception of rejection), and experienced stigma (experiences of discrimination). Personal stigma is linked with a poorer treatment adherence, and worst social functioning. For this reason, it is important to have good measurements of personal stigma. One of the most frequently used measurements is the Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale. There is a Spanish version of the scale available, although its psychometric properties have not been studied. The main aim of this study is to analyse the psychometric properties of a new Spanish version of the ISMI scale.

Material and methodsThe new version was translated as Estigma Interiorizado de Enfermedad Mental (EIEM). Internal consistency and test–retest reliability were calculated in a sample of 69 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. The rate of patients showing personal stigma was also studied, as well as the relationship between personal stigma and sociodemographic and clinical variables.

ResultsThe adapted version obtained good values of internal consistency and test–retest reliability, for the total score of the scale (0.91 and 0.95 respectively), as well as for the five subscales of the EIEM, except for the Stigma Resistance subscale (Cronbach's alpha 0.42).

ConclusionsEIEM is an appropriate measurement tool to assess personal stigma in a Spanish population with severe mental disorder, at least in those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

En ocasiones los pacientes con esquizofrenia asumen como propio el estigma social relacionado con la enfermedad y se origina el denominado estigma personal. El estigma personal implica el autoestigma (interiorización de estereotipos negativos), el estigma percibido (percepción de rechazo) y el estigma experimentado (experiencias de discriminación). El estigma personal se relaciona con peor adherencia al tratamiento y peor funcionamiento social; por tanto, es importante contar con medidas adecuadas del estigma personal. Una de las medidas más utilizadas es la escala Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI). Esta escala está disponible en español, aunque la versión diseñada no se sometió a un análisis psicométrico riguroso. El presente estudio se plantea analizar las propiedades psicométricas de una nueva versión en español de la ISMI.

Material y métodosLa nueva versión se tradujo como Estigma Interiorizado de Enfermedad Mental (EIEM). Se calcularon la consistencia interna y la fiabilidad test-retest en una muestra de 69 pacientes diagnosticados de esquizofrenia o trastorno esquizoafectivo. También se analizó el porcentaje de pacientes que mostraban estigma, y su relación con variables sociodemográficas y clínicas.

ResultadosLa nueva versión obtuvo valores adecuados de consistencia interna y fiabilidad test-retest para el total de la prueba (0,91 y 0,95 respectivamente) y para las 5 subescalas que integran la EIEM, salvo la subescala de Resistencia al estigma (alfa de Cronbach 0,42).

ConclusionesLa EIEM parece una escala adecuada para valorar el estigma personal en población española con trastorno mental grave, al menos en personas con diagnóstico de esquizofrenia o trastorno esquizoafectivo.

One of the consequences of suffering a severe mental disorder is that individuals with schizophrenia have to face the social stigma that arises in connection with the illness. Although fighting stigma is one of the priorities of the Mental Health programmes of the World Health Organisation, different studies show that negative stereotypes are still associated with schizophrenia. These include dangerousness and unpredictability, leading to attitudes of rejection or discrimination.1–3 These findings can also be observed in our environment. Studies undertaken in the general population of Spain indicate that a certain amount of confusion exists regarding mental illness and intellectual disability, and that aggressiveness and violent behaviour are identified as characteristic symptoms of schizophrenia. Likewise, there are still certain attitudes of paternalism and over-protection regarding individuals with mental health problems.4,5

Sometimes patients themselves identify with these negative stereotypes and internalise them. This gives rise to what is known as interiorised stigma or self-stigma, which together with the perceived stigma and experienced stigma form personal stigma.6 Perceived stigma is defined as the negative beliefs and attitudes which schizophrenia patients believe society holds about them. Anticipating these attitudes contributes to the decision of patients to not connect socially and thereby increase their social isolation. In turn, experienced stigma refers to specific behaviour involving rejection, discrimination or the lack of opportunities patients have suffered due to their illness. Personal stigma is found in schizophrenia patients in different countries and cultures, at a prevalence running from 36% to 64%, depending on the study in question.6–8

Personal stigma has been associated with clinical variables such as age at onset of the illness or psychopathological state,6,9 together with sociodemographic variables such as age, educational level or socioeconomic status,10,11 although the latter data are not conclusive.9 In general there is greater agreement on the lack of relationship between gender and the level of stigma expressed by patients.9,10,12 Likewise, personal stigma has a profound impact on the lives of individuals diagnosed with a severe mental disorder. It is associated with loss of self-esteem, depression, an increase in the severity of psychotic symptoms, poor adherence to psychopharmacological treatment, worse social and professional functioning and a lower quality of life.13–17 All of this means that personal stigma hinders recovery in schizophrenia,18 and it considered to be a factor that should be included in the treatment objectives of psycho-social rehabilitation.14,19

The above remarks underline the importance of having suitable instruments to evaluate personal stigma. The Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI)20 scale is one of the most widely used instruments to evaluate stigma in different disorders and cultural contexts.21–25 The ISMI is composed of 29 items and 5 subscales, and it is available in 55 languages, including Spanish.17 A smaller version of this scale was published recently, composed of 10 items, 2 in each subscale.26 This version is offered as a fast way of evaluating personal stigma, and it can be used in broader evaluation protocols. However, it does not replace the more detailed evaluation arising from the 29 item version. In fact, the shorter version gives a single total score, and the authors advise against calculating scores in each subscale.

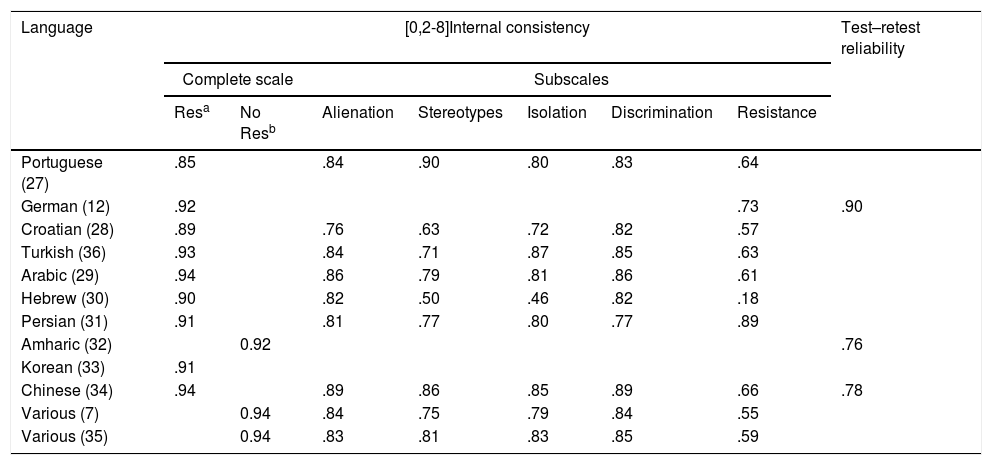

As a whole, the versions of the ISMI developed in other languages7,12,27–36 obtained suitable scores in terms of the internal consistency of scores on the complete scale (from 0.85 to 0.94). Respecting the subscales in the ISMI (see the description of the test under the heading of Instruments), the stigma resistance subscale is the one that gives the poorest scores for internal consistency (Table 1). The same results were found in the original version.7,35 Due to this, some studies have used the ISMI scale while excluding the said subscale.7,32,35 As may be seen in Table 1, test–retest reliability has been studied less in adaptations to other languages.12,32,34

Psychometric properties of versions of the scale Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI).

| Language | [0,2-8]Internal consistency | Test–retest reliability | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete scale | Subscales | |||||||

| Resa | No Resb | Alienation | Stereotypes | Isolation | Discrimination | Resistance | ||

| Portuguese (27) | .85 | .84 | .90 | .80 | .83 | .64 | ||

| German (12) | .92 | .73 | .90 | |||||

| Croatian (28) | .89 | .76 | .63 | .72 | .82 | .57 | ||

| Turkish (36) | .93 | .84 | .71 | .87 | .85 | .63 | ||

| Arabic (29) | .94 | .86 | .79 | .81 | .86 | .61 | ||

| Hebrew (30) | .90 | .82 | .50 | .46 | .82 | .18 | ||

| Persian (31) | .91 | .81 | .77 | .80 | .77 | .89 | ||

| Amharic (32) | 0.92 | .76 | ||||||

| Korean (33) | .91 | |||||||

| Chinese (34) | .94 | .89 | .86 | .85 | .89 | .66 | .78 | |

| Various (7) | 0.94 | .84 | .75 | .79 | .84 | .55 | ||

| Various (35) | 0.94 | .83 | .81 | .83 | .85 | .59 | ||

The Spanish version of the ISMI scale was developed by Doctor Brohan within the context of the GAMIAN7 study. The authors of this paper contact her, and Doctor Brohan herself stated that the “adaptation was undertaken using a simple process of translation and back-translation, and the psychometric properties of the same were not evaluated”. She therefore recommended creating a new version of the scale using more rigorous criteria in the adaptation process. This study therefore aims to create a new adaptation of the scale and to study its psychometric properties, in the original 29-item version as well as the shorter 10-item version. Doctor Boyd was requested to authorise both adaptations. The study also aimed to evaluate whether there are differences in personal stigma depending on sociodemographic variables (sex, age, educational level and socioeconomic status) or clinical variables (age at onset, years of evolution, number of admissions and patient type: outpatient vs. hospitalised).

The working hypotheses were that the scores of the new Spanish version of the ISMI scale would have suitable psychometric properties, and that differences in the level of personal stigma would be detected according to clinical and sociodemographic variables.

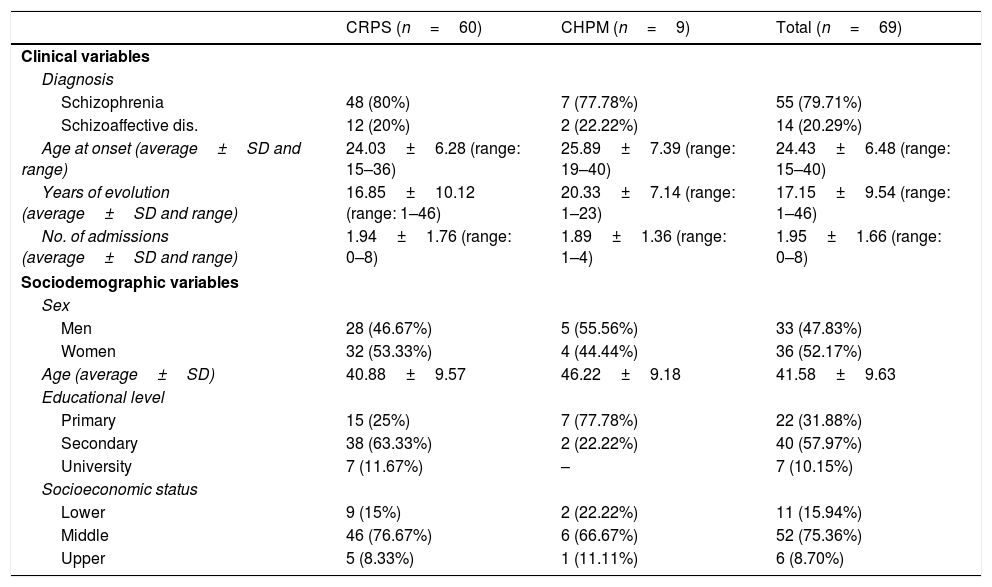

Material and methodsParticipantsSample selection criteria were a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder by the reference psychiatrists in the Cantabrian Health Service, and an age of from 18 to 65 years old. 72 patients were preselected, and 3 of them refused to take part in the study. The new Spanish version of the ISMI scale, translated as the “Estigma Interiorizado de Enfermedad Mental” (EIEM) (Annex 1), was therefore administered to a total of 69 subjects. The majority of the sample consisted of patients diagnosed schizophrenia (79.71%), outpatients (86.95%), women (52.17%), with middle socioeconomic status (75.36%), an average age of 41.58 years old and secondary education (57.97%). The average age at the onset of the illness was 24.43 years old, with 17.15 years of evolution. The sample characteristics are shown in Table 2. All of the patients were treated in the Padre Menni Hospital, Santander. The outpatients were seen in a psychosocial rehabilitation centre, while the hospitalised patients were admitted to a medium to long-stay unit in the said Hospital.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

| CRPS (n=60) | CHPM (n=9) | Total (n=69) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical variables | |||

| Diagnosis | |||

| Schizophrenia | 48 (80%) | 7 (77.78%) | 55 (79.71%) |

| Schizoaffective dis. | 12 (20%) | 2 (22.22%) | 14 (20.29%) |

| Age at onset (average±SD and range) | 24.03±6.28 (range: 15–36) | 25.89±7.39 (range: 19–40) | 24.43±6.48 (range: 15–40) |

| Years of evolution (average±SD and range) | 16.85±10.12 (range: 1–46) | 20.33±7.14 (range: 1–23) | 17.15±9.54 (range: 1–46) |

| No. of admissions (average±SD and range) | 1.94±1.76 (range: 0–8) | 1.89±1.36 (range: 1–4) | 1.95±1.66 (range: 0–8) |

| Sociodemographic variables | |||

| Sex | |||

| Men | 28 (46.67%) | 5 (55.56%) | 33 (47.83%) |

| Women | 32 (53.33%) | 4 (44.44%) | 36 (52.17%) |

| Age (average±SD) | 40.88±9.57 | 46.22±9.18 | 41.58±9.63 |

| Educational level | |||

| Primary | 15 (25%) | 7 (77.78%) | 22 (31.88%) |

| Secondary | 38 (63.33%) | 2 (22.22%) | 40 (57.97%) |

| University | 7 (11.67%) | – | 7 (10.15%) |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Lower | 9 (15%) | 2 (22.22%) | 11 (15.94%) |

| Middle | 46 (76.67%) | 6 (66.67%) | 52 (75.36%) |

| Upper | 5 (8.33%) | 1 (11.11%) | 6 (8.70%) |

CHPM: Centro Hospitalario Padre Menni, hospitalised patients; CRPS: Psychosocial Rehabilitation Centre, outpatients.

The personal and clinical data of each patient were independently recorded by 2 different evaluators, ensuring participant anonymity. The evaluators were both clinical psychologists with experience in administering and correcting psychometric tests, and who had previously been trained in how to apply the test correctly.

InstrumentsThe ISMI scale is a self-administered questionnaire composed of 29 items grouped in 5 sub-scales: Alienation, stereotype interiorisation, social isolation, experiences of discrimination and stigma resistance. The subscales correspond to interiorised stigma or self-stigma (alienation and the interiorisation of stereotypes), perceived stigma (social isolation) and experienced stigma (experiences of discrimination). The stigma resistance subscale evaluates the capacity for resilience against social stigma. All of the items are evaluated on a 4-point Likert scale according to degree of agreement: 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (agree), 4 (strongly agree). The test gives a score for each subscale as well as a total score running from 0 to 4. A score of 2.5 is considered to be the cut-off point for the presence of stigma. The items in the stigma resistance subscale score inversely, so that in this case a score under 2.5 indicates greater resilience. The ISMI has good psychometric properties in the 29 item version (internal consistency of 0.90 and test–retest reliability of 0.92 for the scale as a whole) as well as in the shorter version.26

To adapt the questionnaire into Spanish the guidelines of the International Test Commission for test adaptation were taken into account.37 As the first step, permission was obtained from the authors of the original test and the shorter version. The translation process involved 3 independent translations into the target language (by professional who specialise in mental health subjects). These were then compared and, in the case of disagreement between the translations, the form closest to the original version was selected. The Spanish version was then back-translated into English by a graduate in English philology who was independent of the first group of translators and who had not seen the original test. Some changes were made in the new version vs the Spanish version of Doctor Brohan, such as replacing the word “gente” (people) by “personas” (persons) in the majority of items. The Spanish version and the back-translated English version were revised and approved by Doctor Brohan and Doctor Boyd. The evaluators tried to ensure that the test was applied under the same conditions for all of the participants (the time and place of administration), and they also received training in how to administer the test. Lastly, and as is described below, its internal consistency was analysed together with its test–retest reliability and the degree to which each item is associated with each subscale (the discrimination scale).

Statistical analysesThe total scale and each one of the 5 subscales in the EIEM were analysed for internal consistency using Cronbach's alpha, while Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to examine its test–retest reliability by administering the test twice in a 15 day interval. Six subjects refused the administration of the test for the second time, so that analysis of test–retest reliability took place in a sample of 63 patients. No lost value imputation was considered. As was pointed out in the introduction, the internal consistency and test–retest reliability of the shorter version composed of 10 items were also analysed.

Likewise, and taking the restriction due to sample size into account, confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA) was used to check the underlying dimensional structure of the scale scores. 2 models were tested. On the one hand, a model with a single general factor and on the other, a model with the 45 factors into which the scale is divided. In both cases the covariance matrix was used.

Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to analyse the relationship of the EIEM with the sociodemographic variable of age, while the t-test was used for independent samples for the sex variable and single factor ANOVA was applied to educational level.

Lastly, the association of the EIEM with the clinical variables of age of onset, years of evolution and number of admissions was analysed using Pearson's correlation coefficient. The t-test for independent samples was used to evaluate the differences between outpatients and those who were hospitalised.

Version 19 of the SPSS programme was used for statistical analysis except for CFA, which was undertaken using lessR and lavaan of the R statistics programme.

Ethical aspectsThe study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Cantabria. All of the subjects who took part received an information sheet describing the study objectives, and they signed an informed consent document giving their authorisation to take part in the study. The participants were not paid and nor were they given any other type of incentive to take part in the study.

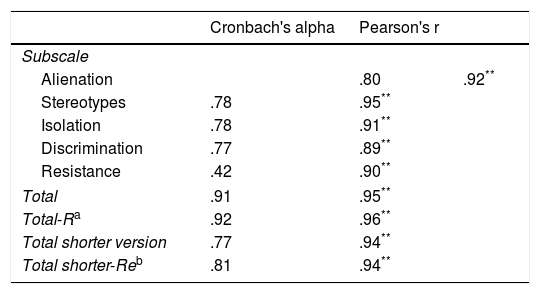

ResultsInternal consistency and stabilityThe 29 item version of the EIEM obtained a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.91. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.77 for the shorter 10 item version. Table 3 shows the internal consistency data for each one of the 5 subscales in the EIEM. As can be seen in this table, all of the subscales have acceptable internal consistency values except for the stigma resistance subscale, which obtained a coefficient of 0.42.

Cronbach's alpha and test–retest reliability for the subscales of the scale Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI).

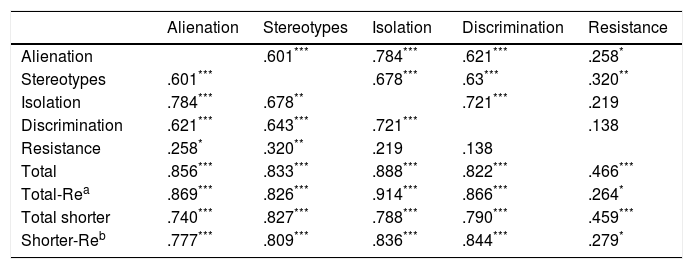

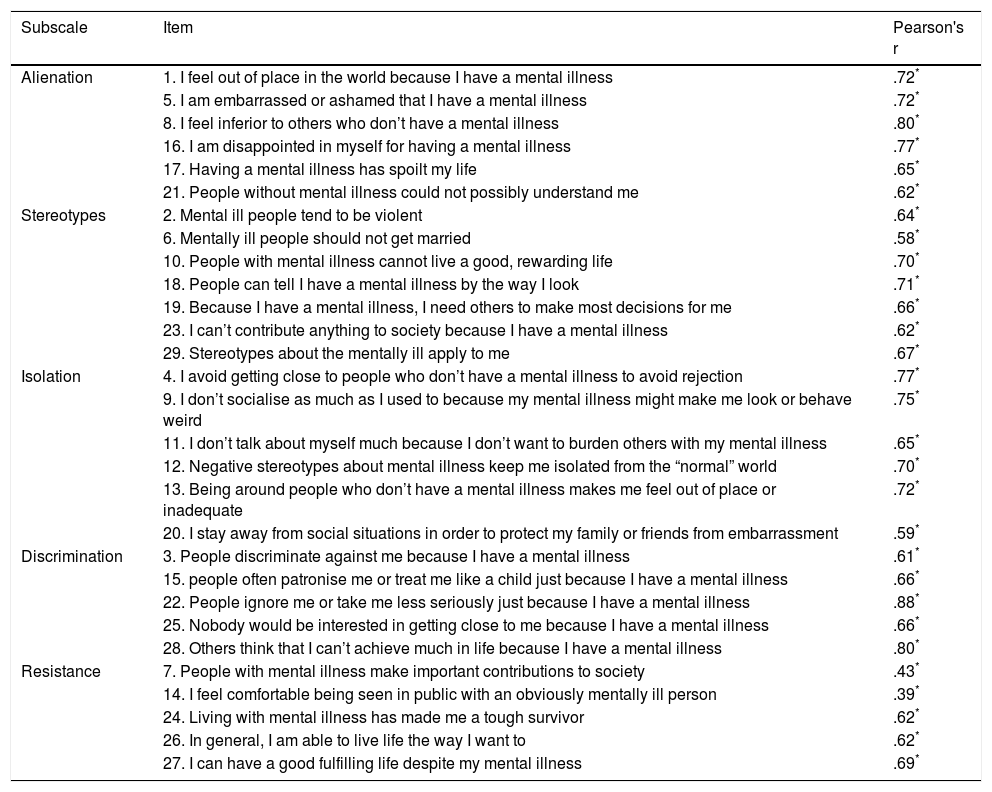

Table 4 shows the correlation between the subscales as well as how they correlate with the total score in the 29 item version as well as in the shorter one. All of the subscales correlate with each other, except for the stigma resistance subscale. The latter only correlates with Alienation and Stereotype Interiorisation, and it obtains no statistically significant correlation with the Social isolation and Discrimination experience subscales. Table 5 shows the discrimination scores of the items in each subscale.

Correlation coefficient between the subscales of the scale Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI).

| Alienation | Stereotypes | Isolation | Discrimination | Resistance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alienation | .601*** | .784*** | .621*** | .258* | |

| Stereotypes | .601*** | .678*** | .63*** | .320** | |

| Isolation | .784*** | .678** | .721*** | .219 | |

| Discrimination | .621*** | .643*** | .721*** | .138 | |

| Resistance | .258* | .320** | .219 | .138 | |

| Total | .856*** | .833*** | .888*** | .822*** | .466*** |

| Total-Rea | .869*** | .826*** | .914*** | .866*** | .264* |

| Total shorter | .740*** | .827*** | .788*** | .790*** | .459*** |

| Shorter-Reb | .777*** | .809*** | .836*** | .844*** | .279* |

Discrimination scores of the items in each subscale.

| Subscale | Item | Pearson's r |

|---|---|---|

| Alienation | 1. I feel out of place in the world because I have a mental illness | .72* |

| 5. I am embarrassed or ashamed that I have a mental illness | .72* | |

| 8. I feel inferior to others who don’t have a mental illness | .80* | |

| 16. I am disappointed in myself for having a mental illness | .77* | |

| 17. Having a mental illness has spoilt my life | .65* | |

| 21. People without mental illness could not possibly understand me | .62* | |

| Stereotypes | 2. Mental ill people tend to be violent | .64* |

| 6. Mentally ill people should not get married | .58* | |

| 10. People with mental illness cannot live a good, rewarding life | .70* | |

| 18. People can tell I have a mental illness by the way I look | .71* | |

| 19. Because I have a mental illness, I need others to make most decisions for me | .66* | |

| 23. I can’t contribute anything to society because I have a mental illness | .62* | |

| 29. Stereotypes about the mentally ill apply to me | .67* | |

| Isolation | 4. I avoid getting close to people who don’t have a mental illness to avoid rejection | .77* |

| 9. I don’t socialise as much as I used to because my mental illness might make me look or behave weird | .75* | |

| 11. I don’t talk about myself much because I don’t want to burden others with my mental illness | .65* | |

| 12. Negative stereotypes about mental illness keep me isolated from the “normal” world | .70* | |

| 13. Being around people who don’t have a mental illness makes me feel out of place or inadequate | .72* | |

| 20. I stay away from social situations in order to protect my family or friends from embarrassment | .59* | |

| Discrimination | 3. People discriminate against me because I have a mental illness | .61* |

| 15. people often patronise me or treat me like a child just because I have a mental illness | .66* | |

| 22. People ignore me or take me less seriously just because I have a mental illness | .88* | |

| 25. Nobody would be interested in getting close to me because I have a mental illness | .66* | |

| 28. Others think that I can’t achieve much in life because I have a mental illness | .80* | |

| Resistance | 7. People with mental illness make important contributions to society | .43* |

| 14. I feel comfortable being seen in public with an obviously mentally ill person | .39* | |

| 24. Living with mental illness has made me a tough survivor | .62* | |

| 26. In general, I am able to live life the way I want to | .62* | |

| 27. I can have a good fulfilling life despite my mental illness | .69* |

Taking the results of the stigma resistance subscale into account, it was decided to do all statistical analyses in duplicate, including and excluding the said subscale.

ReliabilityThe test–retest reliability of the EIEM was 0.95 (P<.001) and .94 (P<.001) for the 29 and 10 item versions, respectively. Table 3 shows the test–retest reliability data for each one of the 5 subscales in the EIEM.

Confirmatory factorial analysisWhen all of the statistical analyses were performed including or excluding the stigma resistance subscale, 3 models were actually tested using CFA. For the model with a single general factor the adjustment index values were: CFI=.71, TLI=.69 and RMSEA=.08. The values for the 5 factor model were: CFI=.81, TLI=.79 and RMSEA=.07. When the Stigma resistance subscale was excluded these values improved: CFI=.87, TLI=.85 and RMSEA=.06. Although in the 4 factor model the adjustment indexes are close to satisfactory values, they remained under the reference value of .90, and this may be due to the size of the sample.

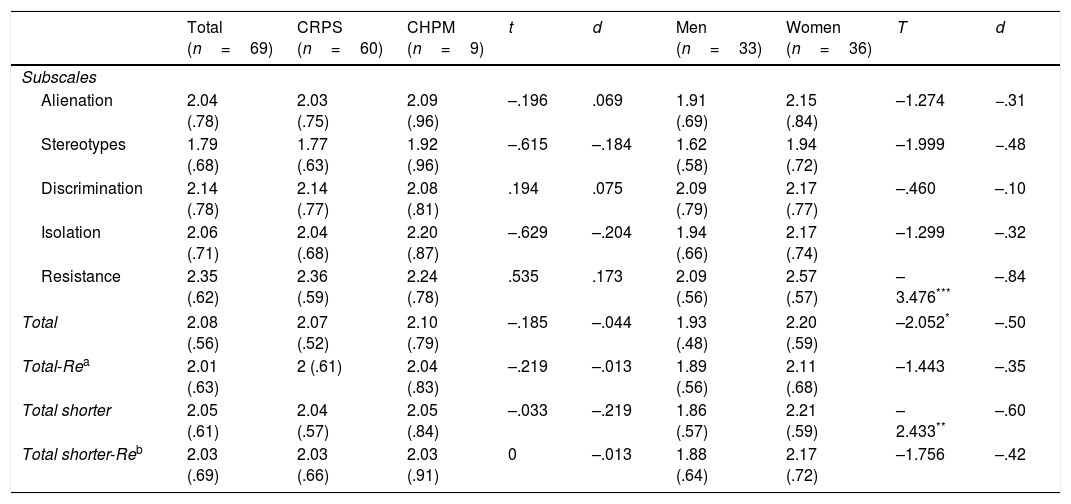

Association with sociodemographic variablesIn terms of their relationship with the sociodemographic variables, the comparison between men and women showed statistically significant differences in the Stigma resistance subscale (t=−3.476, gl=67, P=.001), and in the total score of the scale. This was so in the complete version (t=−2.052, gl=67, P=.044) as well as in the shorter version (t=−2.433, gl=67, P=.018). In all cases the average score of the women was significantly higher than the men's score. Nevertheless, when the Stigma resistance subscale is excluded the differences between men and women are annulled (Table 6). Neither age nor educational level showed any statistically significant correlation with any of the EIEM subscales.

Average scores and standard deviations in the subscales of the scale Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI).

| Total (n=69) | CRPS (n=60) | CHPM (n=9) | t | d | Men (n=33) | Women (n=36) | T | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subscales | |||||||||

| Alienation | 2.04 (.78) | 2.03 (.75) | 2.09 (.96) | –.196 | .069 | 1.91 (.69) | 2.15 (.84) | –1.274 | −.31 |

| Stereotypes | 1.79 (.68) | 1.77 (.63) | 1.92 (.96) | –.615 | –.184 | 1.62 (.58) | 1.94 (.72) | –1.999 | −.48 |

| Discrimination | 2.14 (.78) | 2.14 (.77) | 2.08 (.81) | .194 | .075 | 2.09 (.79) | 2.17 (.77) | –.460 | –.10 |

| Isolation | 2.06 (.71) | 2.04 (.68) | 2.20 (.87) | –.629 | –.204 | 1.94 (.66) | 2.17 (.74) | –1.299 | –.32 |

| Resistance | 2.35 (.62) | 2.36 (.59) | 2.24 (.78) | .535 | .173 | 2.09 (.56) | 2.57 (.57) | –3.476*** | –.84 |

| Total | 2.08 (.56) | 2.07 (.52) | 2.10 (.79) | –.185 | –.044 | 1.93 (.48) | 2.20 (.59) | –2.052* | –.50 |

| Total-Rea | 2.01 (.63) | 2 (.61) | 2.04 (.83) | –.219 | –.013 | 1.89 (.56) | 2.11 (.68) | –1.443 | –.35 |

| Total shorter | 2.05 (.61) | 2.04 (.57) | 2.05 (.84) | –.033 | –.219 | 1.86 (.57) | 2.21 (.59) | –2.433** | –.60 |

| Total shorter-Reb | 2.03 (.69) | 2.03 (.66) | 2.03 (.91) | 0 | –.013 | 1.88 (.64) | 2.17 (.72) | –1.756 | –.42 |

CHPM: Centro Hospitalario Padre Menni, hospitalised patients; CRPS: Psychosocial Rehabilitation Centre, outpatients.

No statistically significant correlation was found between the clinical variables analysed (age at onset, years of evolution, number of admissions and patient type) and the EIEM scores. This was the case in the total score as well as in the subscales it contains.

For the sample as a whole as well as when it is divided according to patient type the average score in all of the subscales was below the cut-off point (Table 6). The percentage of patients above this score in the total sample was as follows: alienation: 33.3%; stereotype interiorisation: 17.4%; social isolation: 36.2%; experiences of discrimination: 34.8%; stigma resistance: 37.7%; total: 26.1%, and for the shorter version: 26.1%.

DiscussionThe aim of this study was to validate a Spanish version of the ISMI scale, translated as the “Estigma Interiorizado de Enfermedad Mental” (EIEM). EIEM scores were found to have good psychometric properties in the 29 item version as well as in the shorter 10 item version. Appropriate test–retest reliability and Cronbach's alpha internal consistency values were found in both cases. Based on these results, the EIEM seems to be a suitable scale for evaluating personal stigma in the Spanish population with a severe mental disorder, at least in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. As Doctor Boyd herself recommends,26 it should be kept in mind that although both versions give similar scores, the shorter version of the EIEM should only be used as a fast screening technique for the existence of personal stigma, and that it is not possible to use it to replace the more detailed evaluation offered by the complete scale.

All of the internal consistency and rest–retest reliability scores in the EIEM subscales were suitable, except for those of the Stigma resistance subscale which displayed weak internal consistency. This datum was also found in previous studies of the original scale7,20 as well as adaptations in other languages.28–30,36 Ritsher et al.20 state that it is necessary to study the use of this subscale within the EIEM as a whole, given that in their study 4 of the 5 items in the Stigma resistance subscale showed low correlation with the interiorised stigma construct. In line with these results, and also based on the low correlation of this subscale with the others, it has been suggested that the concept of stigma resistance is a different construct that is differentiated from personal stigma.12,38 The CFA results obtained in this study seem to support this conclusion, as when the Stigma resistance subscale is excluded, and taking the limited sample size into account, the CFA data improved and approached satisfactory levels, even though they remained below recommended values.

Unlike previous studies, which locate the prevalence of personal stigma in schizophrenia patients at levels from 36% to 64%,6–8 this study detected a prevalence of 26.1%. Analysis of the percentages obtained in each subscale makes it possible to check that, except for the stereotype interiorisation subscale, in the others at least 33% of the sample score above 2.5. The results in these subscales are more similar to those obtained in other studies, and they make it possible to state that at least one third of patients say that they feel ashamed of having the illness, expect to be rejected by society and experience or have experienced discrimination due to their sickness. As was pointed out above, and in agreement with previous studies,7,12,39 negative stereotypes are the least interiorised. I.e., the majority of these patients do not identify with the stereotypes associated with schizophrenia or accept them as their own. These stereotypes include dangerousness, unpredictability or an inability to reach decisions independently. The low percentage of patients in the sample who identify with these stereotypes may be explained by the fact that the majority of them attend a psychosocial rehabilitation clinic where specific programmes treat this field.

The results obtained in this study in connection with the sociodemographic variables support the hypothesis that the level of personal stigma is independent of the age and educational level of the patients.12,40 Contrary to this conclusion, 2 previous studies found that there is an inverse relationship between age and personal stigma; i.e., that older patients express less stigma than younger ones.11,41 Nevertheless, these studies included subjects over the age of 65 years old, so that their results are not comparable with those of our study, as the latter contains no subjects above this age. It must also be pointed out that the study by Sirey et al.41 was undertaken in individuals diagnosed with depression. Respecting the association between the sex and stigma variables, unlike previous studies12,40 women were found to have a higher level of stigma in the Stigma resistance subscale. It may therefore be concluded that women have less resilience against stigma, and that their ability to live a satisfactory life is more affected by this. Statistically significant differences were also detected between men and women in terms of their total score in the complete and shorter versions of the EIEM. However, these differences disappear when the Stigma resistance subscale is excluded. It therefore seems that once the difference due to this subscale is eliminated, men and women do not differ in the level of interiorised stigma they perceive or experience.

No statistically significant association was detected regarding the clinical variables, as no relationship was found between the study variables and the EIEM subscales. These data do not agree with those of previous studies6,9; however, it must be pointed out that the majority of patients in this study are in a psychosocial rehabilitation programme, and this may affect the data obtained.

Lastly, the outpatients were found to express more personal stigma than those who were hospitalised.22,42 Segalovich et al.43 attribute this to the fact that patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital are in an environment where their peers have a similar mental disorder, so that the experience or possibility of being labelled as or feeling inferior is less probable than is the case when they live in the community. Our study found no differences between stigma level in outpatients and those who were hospitalised. This difference in comparison with previous studies may be due to the low percentage of hospitalised patients in the sample studied (13.05%), and this may not be representative of the typical profile of patients admitted to medium to long-term units. Another explanation may arise due to the different cultural context in which the said studies were conducted, as one took place in India22 and the other in Israel.42 In any case, this result has to be accepted cautiously, and further studies will be necessary to evaluate this difference and supply more conclusive data.

The chief limitation of this study arises due to the size and characteristics of the sample used. Respecting its size, statistical analysis was undertaken using samples of 69 and 63 subjects, depending on the statistic used, so that it would be necessary to repeat them in a larger sample to gain more representative data. Regarding the sample characteristics, as the majority of patients attend a psychosocial rehabilitation centre where some programmes centre specifically on stigma, the results obtained may not be representative of patients with other characteristics, above all in the case of their first episodes. Likewise, the fact that only 9 patients in the total sample were hospitalised means that the lack of difference in stigma between outpatients and those who were hospitalised has to be accepted with caution. This is also the case for the lower resilience in the case of the women, given that this datum is not confirmed by other studies.

Lastly, in future studies it would be of interest to check the validity of the EIEM in evaluating personal stigma in the case of other diagnoses, as well as in psychotic patients with characteristics other than those of the sample in this study. Thus recently Bernardo et al.44 studied the clinical and neurophysiological characterisation of patients in their first psychotic episode. It would be of interest to include measurements such as the EIEM in studies of this type, to evaluate the presence and evolution of personal stigma from the first phases of psychosis.

To conclude, the results of this study indicate that EIEM scores have suitable internal consistency and reliability values. A 26% prevalence of personal stigma was found in the sample used and, taken as a whole, the data obtained support the hypothesis that the presence of stigma is independent of sociodemographic as well as clinical variables.

Ethical disclosuresThe protection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments took place in human beings or animals for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their hospital regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this paper.

FundingBorja Santos-Zorrozúa receives a grant from the Programa Predoctoral de Formación de Personal Investigador No Doctor of the Basque Government Department of Education, Linguistic Policy and Culture.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors would like to thank the philologist Sandra Peredo for her work in back-translating the scale.

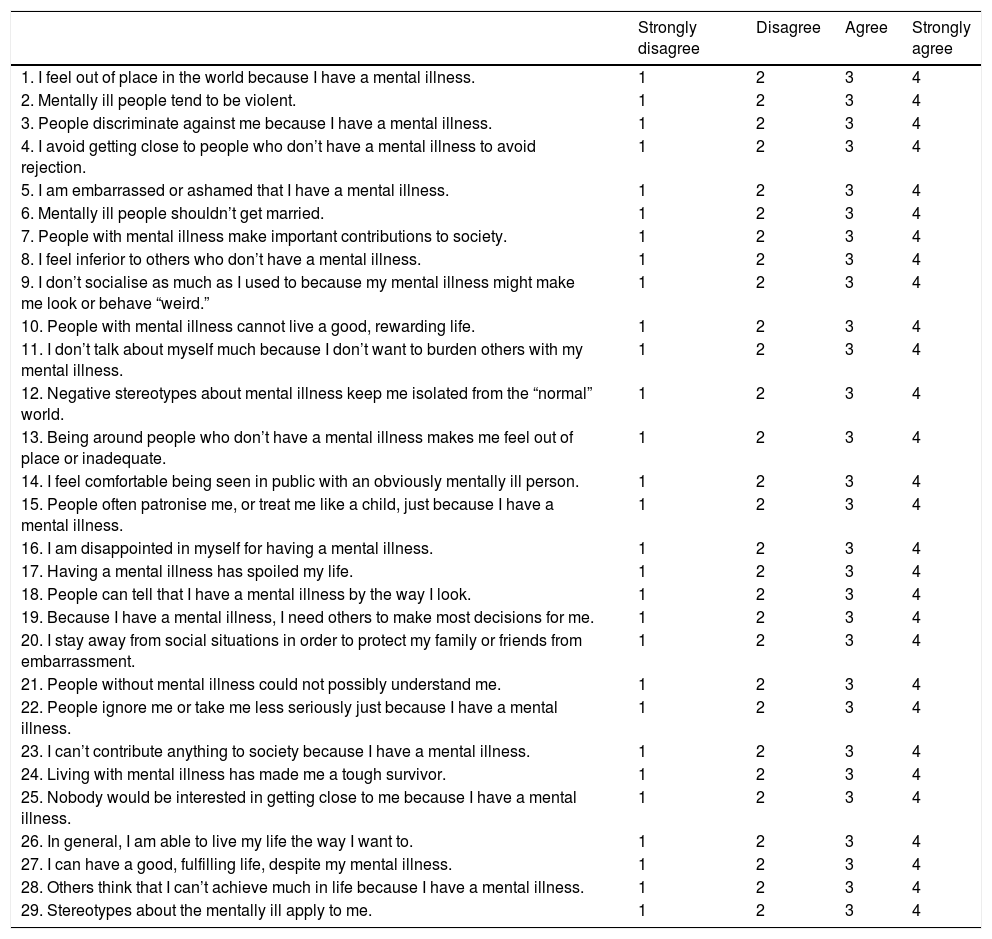

Name: Date:

We are going to use the term “mental illness” in the rest of this questionnaire, but please think of it as whatever you feel is the best term for it.

For each question, please mark whether you strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), agree (3), or strongly agree (4).

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I feel out of place in the world because I have a mental illness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. Mentally ill people tend to be violent. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. People discriminate against me because I have a mental illness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. I avoid getting close to people who don’t have a mental illness to avoid rejection. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. I am embarrassed or ashamed that I have a mental illness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. Mentally ill people shouldn’t get married. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7. People with mental illness make important contributions to society. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8. I feel inferior to others who don’t have a mental illness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9. I don’t socialise as much as I used to because my mental illness might make me look or behave “weird.” | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10. People with mental illness cannot live a good, rewarding life. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11. I don’t talk about myself much because I don’t want to burden others with my mental illness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12. Negative stereotypes about mental illness keep me isolated from the “normal” world. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13. Being around people who don’t have a mental illness makes me feel out of place or inadequate. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 14. I feel comfortable being seen in public with an obviously mentally ill person. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 15. People often patronise me, or treat me like a child, just because I have a mental illness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 16. I am disappointed in myself for having a mental illness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 17. Having a mental illness has spoiled my life. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 18. People can tell that I have a mental illness by the way I look. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 19. Because I have a mental illness, I need others to make most decisions for me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 20. I stay away from social situations in order to protect my family or friends from embarrassment. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 21. People without mental illness could not possibly understand me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 22. People ignore me or take me less seriously just because I have a mental illness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 23. I can’t contribute anything to society because I have a mental illness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 24. Living with mental illness has made me a tough survivor. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 25. Nobody would be interested in getting close to me because I have a mental illness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 26. In general, I am able to live my life the way I want to. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 27. I can have a good, fulfilling life, despite my mental illness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 28. Others think that I can’t achieve much in life because I have a mental illness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 29. Stereotypes about the mentally ill apply to me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Please cite this article as: Bengochea-Seco R, Arrieta-Rodríguez M, Fernández-Modamio M, Santacoloma-Cabero I, Gómez de Tojeiro-Roce J, García-Polavieja B, et al. Adaptación al español de la escala Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness para valorar el estigma personal. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2018;11:244–254.