Studies of executive function in autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability (ASD-WID) patients are contradictory. We assessed a wide range of executive functioning cognitive domains in a sample of children and adolescents with ASD-WID and compared them with age-, sex-, and intelligence quotient (IQ)-matched healthy controls.

MethodsTwenty-four ASD-WID patients (mean age 12.8±2.5 years; 23 males; mean IQ 99.20±18.81) and 32 healthy controls (mean age 12.9±2.7 years; 30 males; mean IQ 106.81±11.02) were recruited.

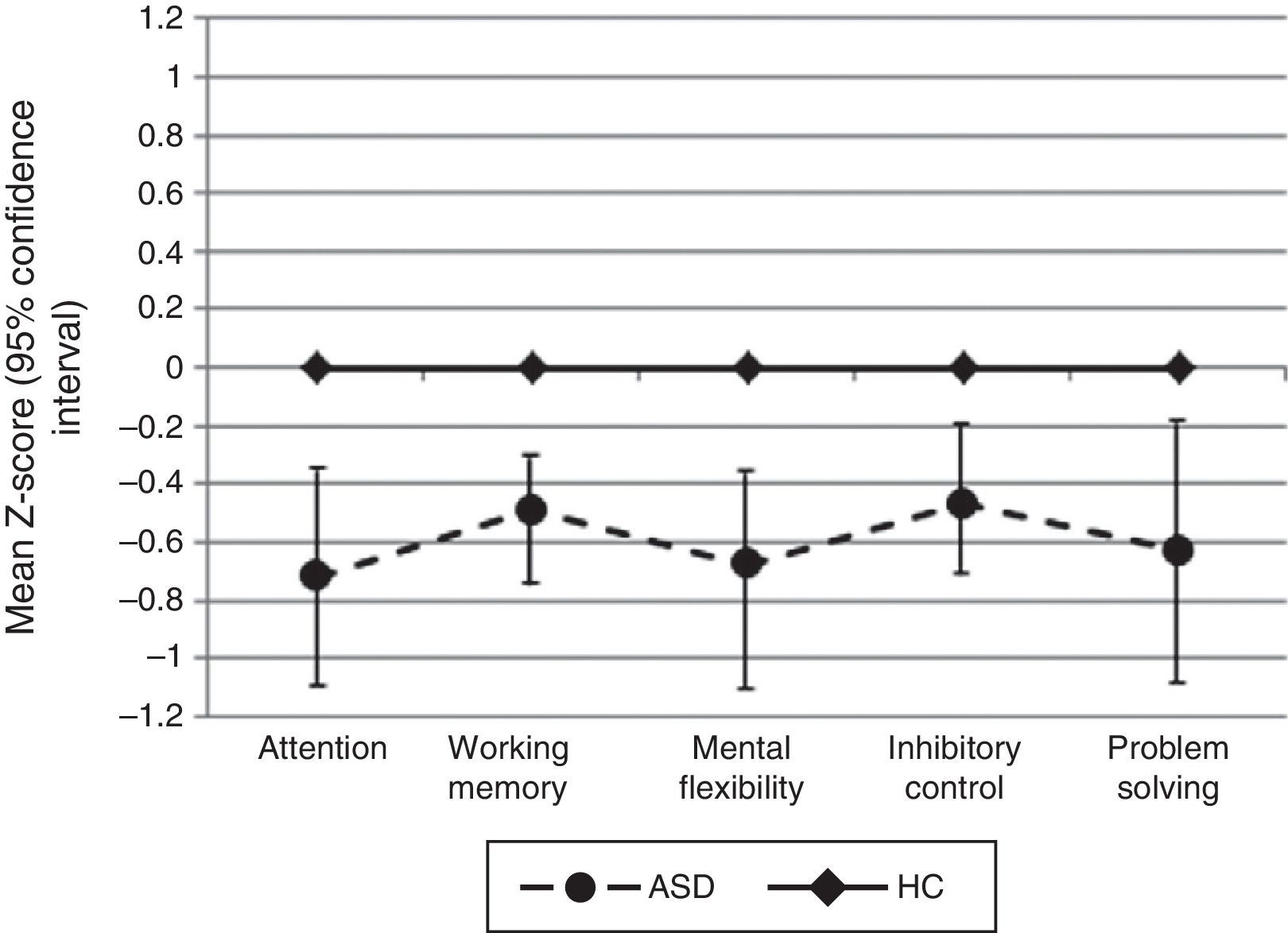

ResultsStatistically significant differences were found in all cognitive domains assessed, with better performance by the healthy control group: attention (U=185.0; p=0.0005; D=0.90), working memory (T51.48=2.597; p=0.006; D=0.72), mental flexibility (U=236.0; p=0.007; D=0.67), inhibitory control (U=210.0; p=0.002; D=0.71), and problem solving (U=261.0; p=0.021; D=0.62). These statistically significant differences were also found after controlling for IQ.

ConclusionChildren and adolescents with ASD-WID have difficulties transforming and mentally manipulating verbal information, longer response latency, attention problems (difficulty set shifting), trouble with automatic response inhibition and problem solving, despite having normal IQ. Considering the low executive functioning profile found in those patients, we recommend a comprehensive intervention including work on non-social problems related to executive cognitive difficulties.

Los estudios reflejan datos contradictorios sobre un posible deterioro en el funcionamiento ejecutivo en niños y adolescentes con trastorno del espectro autista sin discapacidad intelectual (TEA-SDI). El objetivo del estudio es evaluar el perfil cognitivo de funcionamiento ejecutivo en niños y adolescentes con TEA-SDI y compararlo con el de controles sanos pareados en sexo, edad, estatus socioeconómico, nivel educacional y cociente intelectual (CI).

MétodosVeinticuatro pacientes con TEA-SDI (edad media 12,8±2,5 años; 23 varones; media de CI 99,20±18,81) y 32 controles (edad media 12,9±2,7 años; 30 varones; media de CI 106,81±11,02) fueron seleccionados.

ResultadosSe encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en todos los dominios cognitivos evaluados a favor de un mejor rendimiento por parte del grupo control: atención (U=185,0; p=0,0005; D=0,90), memoria de trabajo (T51,48=2,597; p=0,006; D=0,72), flexibilidad cognitiva (U=236,0; p=0,007; D=0,67), control inhibitorio (U=210,0; p=0,002; D=0,71) y solución de problemas (U=261,0; p=0,021; D=0,62). Estas diferencias se mantuvieron cuando se realizaron los análisis controlando por CI.

ConclusiónLos niños y adolescentes con TEA-SDI tienen dificultades para transformar y manipular mentalmente información verbal, presentan latencias de respuesta mayores, problemas atencionales (dificultades en el cambio del set), problemas en la inhibición de respuestas automáticas, así como en la solución de problemas, a pesar de tener un CI normal. Teniendo en cuenta las dificultades en funcionamiento ejecutivo de estos pacientes, se recomienda una intervención integral, que incluya el trabajo en este tipo de dificultades.

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have social communication deficits starting early in life and stereotyped, repetitive behaviors and/or hyper/hyporeactivity to sensory input.

The relationship between executive function (EF) and autism is much debated.1 The literature yields contradictory results about impairment or normal performance in ASD of attention,1–8 working memory,8–14 mental flexibility,2,4,8,15 inhibitory control,3–8,15–18 and problem solving tasks,4,19 all of which are generally considered part of EF. However, EF is not a unitary construct.20 The term EF often includes a set of cognitive processes such as planning, working memory, attention, problem solving, verbal reasoning, inhibition, mental flexibility, multi-tasking, and initiation and monitoring of actions,21 another way of putting it is that it is an umbrella term for neurologically-based skills involving mental control and self-regulation. In short, EFs are the higher order control processes necessary to guide behavior.22

We aimed at studying EF in patients with high functioning autism and comparing this EF with a measure of general intelligence, with the ultimate goal of reporting empirical information about the non-social deficits of this population; this would help designing appropriate neuropsychological rehabilitation programs. The specific objectives of the study were: to evaluate the EF of a homogeneous sample of children and adolescents with ASD without intellectual disability (ASD-WID), using a comprehensive neuropsychological battery, and compare their scores with those of a group of matched healthy controls (HC). We also wanted to explore whether deficits in EF correlated with daily functioning or severity of the disorder.

Our hypothesis was that children and adolescents with ASD-WID would have significantly lower scores on a range of EF tasks, i.e., attention, working memory, mental flexibility, inhibitory, control and problem solving, than an HC group matched for age, education years, and intelligence quotient (IQ).

MethodsParticipantsASD patient recruitment was conducted at the outpatient Child and Adolescent Department of Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain between May 2005 and February 2009.23 The HC group was recruited in schools with socio-demographic characteristics similar to patients (from schools in the same area and of similar socioeconomic status).

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (a) age between 7 and 18 years of age; (b) Spanish as a first mother tongue; (c) diagnosis of ASD-WID (defined in the DSM-IV as Asperger syndrome (AS)) or high functioning autism (HFA), (d) availability of a complete EF assessment. The exclusion criteria were: (a) comorbid Axis I disorder at the time of enrollment; (b) history of head injury with loss of consciousness; (c) intelligence quotient <70; (d) significant disease unrelated to ASD; (e) pregnancy and lactation; and (f) substance abuse or dependence. In the HC group, inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same, with the exception of the presence of ASD.

After receiving a full explanation of the study, all parents or legal guardians gave written informed consent, and patients gave their assent to participate. The study was approved by the Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

MeasuresDemographic and clinical dataDemographic data were collected using a structured interview with the participants and their parents or legal guardians. The Hollingshead-Redlich Scale24 was assessed to calculate parental socioeconomic status (SES).

All ASD diagnoses were made by child psychiatrists. The diagnosis procedure included a full developmental medical and psychiatric history and observation in a clinical setting. A gold standard diagnostic procedure was performed by psychiatrists of the Hospital Gregorio Marañón Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Department with more than 10 years of experience. The criteria of the Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)25 and Gillberg criteria26 were used; the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic (ADOS-G)27 was administered by ADOS research-certified clinicians when DSM-IV criteria and Gillberg criteria were inconsistent (10 patients with ASD (35.7%)). The Kiddie-SADS-Present and Lifetime Version interview (K-SADS)28 was administered to rule out comorbid psychiatric disorders in the ASD group and psychiatric conditions in HC group. Medication was recorded.

Psychosocial functioning was assessed with the Children's Global Assessment of Functioning (C-GAS) scale,29 Spanish version.30 C-GAS scores >70 are considered good.31

Severity of global symptomatology was assessed with the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI)32 in the ASD group.

Intelligence quotient assessmentGiven that Estimated Intelligence Quotient (EIQ) is not a reliable measurement in patients with ASD-WID,33 the Full Intelligence Quotient test (FIQ) was administered to the ASD group, using the Spanish translation of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Adults-third edition (WAIS-III) or the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised (WISC-R),34,35 according to age.

Intelligence profiles were estimated in the HC group using Vocabulary and Block Design subtests36 of the WAIS-III or WISC-R.

Executive function assessmentEF was assessed using a neuropsychological battery composed of the following tests:

Stroop Color and Word Test (Stroop), whose reliability has proven very consistent (ranging from 0.73 to 0.86).37,38 This is a classic verbal response inhibition task.

Trail Making Test (TMT),39 whose reliability in clinical groups ranges from 0.69 to 0.94 for part A and from 0.66 to 0.86 for part B.40 TMT is a test of processing speed and set shifting. In this test we calculated the following score: derived score from TMT(B)=(time to complete TMT(B)−time to complete TMT(A))/time to complete TMT(A).

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST-table version) for which generalizability of the different component variables range from 0.52 to 0.71.41 WCST is a measure of concept generation, cognitive set shifting, ability to inhibit prepotent responses, attribute identification, abstract reasoning, hypothesis testing and problem solving, and sustained attention.42

Continuous Performance Test-II (CPT-II), for which internal consistency of the different component variables ranges from 0.83 to 0.94.43 This measures sustained attention, impulse control, and information processing speed.

Digit span and Letter-Number sequencing (WAIS-III), with a validity and reliability index of 0.82 and from 0.60 to 0.80, respectively.34

Digit Span Forward is an attention task and Digit Span Backward is a verbal working memory task that measures the ability to transform and mentally manipulate information. We used the span obtained by the participant in this subtest.

Letter-Number sequencing is a working memory task that measures the ability to transform and mentally manipulate information. We used the span obtained by the participant in this subtest.

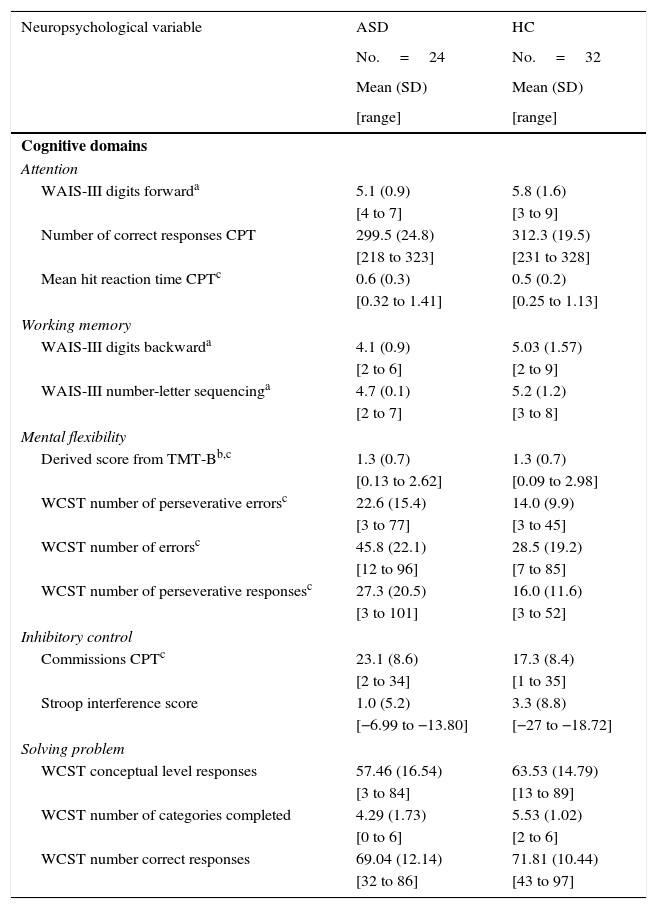

Five domains of EF (attention, working memory, mental flexibility, inhibitory control, and problem solving) were constructed by selected individual measures from the aforesaid tests. Decisions about grouping individual neuropsychological measurements of each test into cognitive domains (Table 1) were based on the cognitive functions assessed by the tests.44–46

Cognitive domains and raw scores for autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability and healthy controls.

| Neuropsychological variable | ASD | HC |

|---|---|---|

| No.=24 | No.=32 | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| [range] | [range] | |

| Cognitive domains | ||

| Attention | ||

| WAIS-III digits forwarda | 5.1 (0.9) | 5.8 (1.6) |

| [4 to 7] | [3 to 9] | |

| Number of correct responses CPT | 299.5 (24.8) | 312.3 (19.5) |

| [218 to 323] | [231 to 328] | |

| Mean hit reaction time CPTc | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.2) |

| [0.32 to 1.41] | [0.25 to 1.13] | |

| Working memory | ||

| WAIS-III digits backwarda | 4.1 (0.9) | 5.03 (1.57) |

| [2 to 6] | [2 to 9] | |

| WAIS-III number-letter sequencinga | 4.7 (0.1) | 5.2 (1.2) |

| [2 to 7] | [3 to 8] | |

| Mental flexibility | ||

| Derived score from TMT-Bb,c | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) |

| [0.13 to 2.62] | [0.09 to 2.98] | |

| WCST number of perseverative errorsc | 22.6 (15.4) | 14.0 (9.9) |

| [3 to 77] | [3 to 45] | |

| WCST number of errorsc | 45.8 (22.1) | 28.5 (19.2) |

| [12 to 96] | [7 to 85] | |

| WCST number of perseverative responsesc | 27.3 (20.5) | 16.0 (11.6) |

| [3 to 101] | [3 to 52] | |

| Inhibitory control | ||

| Commissions CPTc | 23.1 (8.6) | 17.3 (8.4) |

| [2 to 34] | [1 to 35] | |

| Stroop interference score | 1.0 (5.2) | 3.3 (8.8) |

| [−6.99 to −13.80] | [−27 to −18.72] | |

| Solving problem | ||

| WCST conceptual level responses | 57.46 (16.54) | 63.53 (14.79) |

| [3 to 84] | [13 to 89] | |

| WCST number of categories completed | 4.29 (1.73) | 5.53 (1.02) |

| [0 to 6] | [2 to 6] | |

| WCST number correct responses | 69.04 (12.14) | 71.81 (10.44) |

| [32 to 86] | [43 to 97] | |

ASD, Autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability; CPT-II, continuous performance test-II; HC, healthy controls; SD, standard deviation; TMT (A–B), trail making test (parts A and B); WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

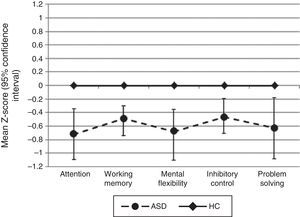

In order to obtain summary scores for each cognitive domain, individual raw scores obtained in each neuropsychological measure were transformed to z-scores (mean=0±1) based on the performance of the HC (using controls’ mean and standard deviation raw scores from each neuropsychological measure according to the formula: (z=X1−X¯2/o˜2); where X1 is the raw score of each ASD patient on the neuropsychological measure, and X¯2 and o˜2 were the HC mean and standard deviation raw score from each neuropsychological measure, respectively). The mean summary scores were calculated as the arithmetic means of the individual measurements that composed the specific cognitive domains (mean of the z-scores). All z-scores were calculated in such a way that higher scores always reflected better performance. For cognitive measures where a higher raw score was indicative of poorer performance (derived score from TMT-B, WCST number of perseverative errors, WCST number of errors, WCST number of perseverative responses, CPT error commission, CPT mean hit reaction time), the z-score sign was changed from plus to minus, and vice versa. Z-scores for individual neuropsychological measures grouped into a given functional domain were averaged to establish a summary score for each domain.

The neuropsychological battery was administered to ASD patients and HC in a quiet room. Tasks were presented in a pre-established order. All tests were administrated and scored according to published instructions by one of three experienced neuropsychologists. Prior to the study, all the neuropsychologists demonstrated good inter-rater reliability in administering and scoring all neuropsychological tests. Inter-rater reliability was calculated for vocabulary subtests (WAIS-III/WISC-R) and WCST by examining 10 cases with interclass correlation coefficients ranging 0.95–1.00 for both tests.

Statistical analysisFor descriptive purposes, mean and standard deviation are provided for continuous variables and discrete variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages.

The discrete variable (sex) was analyzed with a chi-square test (χ2), and a Fisher's exact test was used to compare race and parental socioeconomic status between groups.

After testing the assumptions of the generalized linear model of the quantitative variables (age, education years, neuropsychological measures, cognitive domains, C-GAS, and CGI) were assessed by means of a Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk, Student's t-test, or Mann–Whitney U-test for normally and not normally distributed variables, respectively.

In order to further investigate the relationship between EF and IQ, bivariate correlation analyses between the cognitive domains and FSIQ, verbal-IQ (VIQ), and manipulative-IQ (MIQ) were assessed in ASD using Spearman's or Pearson's coefficients as needed.

Although our sample was matched by IQ, we also evaluated the differences between ASD patients and HC in EF domains with a general linear model analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with group (ASD/HC) as a fixed factor, z-scores of each EF domains as dependent variables, and IQ as a covariate.

To investigate the relationship between cognitive domains and functioning and severity (C-GAS and CGI) in ASD patients, we also used Spearman's or Pearson's coefficients.

Effects sizes were calculated for all statistically significant differences. We reported them with Cohen's d coefficient (according to Cohen, 0.2 is indicative of a small, 0.5 of a medium, and 0.8 of a large effect size). Due to the relatively limited number of patients available and in order to rule out possible type II error, we also calculated statistical power in all variables for which we did not find statistical significance between groups.

A significance p-value threshold was set at <0.05. The analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 for Windows.

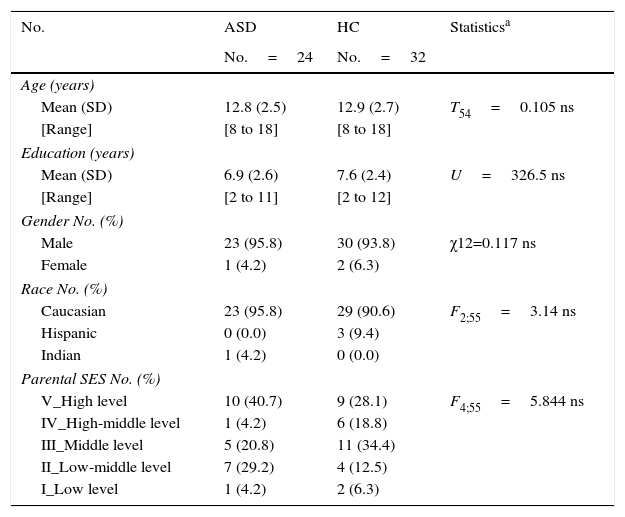

ResultsParticipantsDemographic and clinical dataTwenty-four ASD patients (22 AS and 2 HFA according to DSM-IV criteria) and 32 HC met the inclusion criteria for this study. There were no statistically significant differences in any demographic variable between ASD patients and the HC group (age, education years, sex, race, parental SES). These are shown in Table 2.

Demographic data.

| No. | ASD | HC | Statisticsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| No.=24 | No.=32 | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 12.8 (2.5) | 12.9 (2.7) | T54=0.105 ns |

| [Range] | [8 to 18] | [8 to 18] | |

| Education (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 6.9 (2.6) | 7.6 (2.4) | U=326.5 ns |

| [Range] | [2 to 11] | [2 to 12] | |

| Gender No. (%) | |||

| Male | 23 (95.8) | 30 (93.8) | χ12=0.117 ns |

| Female | 1 (4.2) | 2 (6.3) | |

| Race No. (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 23 (95.8) | 29 (90.6) | F2;55=3.14 ns |

| Hispanic | 0 (0.0) | 3 (9.4) | |

| Indian | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Parental SES No. (%) | |||

| V_High level | 10 (40.7) | 9 (28.1) | F4;55=5.844 ns |

| IV_High-middle level | 1 (4.2) | 6 (18.8) | |

| III_Middle level | 5 (20.8) | 11 (34.4) | |

| II_Low-middle level | 7 (29.2) | 4 (12.5) | |

| I_Low level | 1 (4.2) | 2 (6.3) | |

ASD, Autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability; HC, healthy controls; SD, standard deviation. SES, parental socioeconomic status, assessed using the Hollinshead Scale (ranging from 1 to 5). A rating of five corresponds to the highest SES and a rating of 1 means the lowest SES; ns, non-significative.

Differences were found in C-GAS between ASD and HC (ASD: mean score 53.25±12.8 (95% confidence interval (CI) [47.9–58.7]), range 35–85, and median 50; HC: mean score 92.52±5.07 (95% CI [90.6–94.5]), range 75–100, and median 91; U: 1.0, p<0.0001).

According to the CGI score, 8 patients (33.3%) were mildly ill, 9 patients (37.5%) were moderately ill, 6 (25%) were markedly ill and 1 (4.2%) was severely ill.

MedicationEight ASD patients (39.29%) were taking psychopharmacological drugs (one patient was taking aripiprazole; two were taking risperidone; one was taking risperidone and sertraline; one was taking risperidone and fluoxetine; one was taking risperidone, methylphenidate and topiramate; and two were taking methylphenidate only).

Intelligence quotient assessmentThe mean EIQ in the HC was 106.81±11.02. In the ASD group, the mean FIQ was 99.20±18.81. No statistically significant differences were found between groups.

Executive function assessmentThe mean raw scores, standard deviation, and range for ASD patients and the HC group on each of the cognitive measure are presented in Table 1.

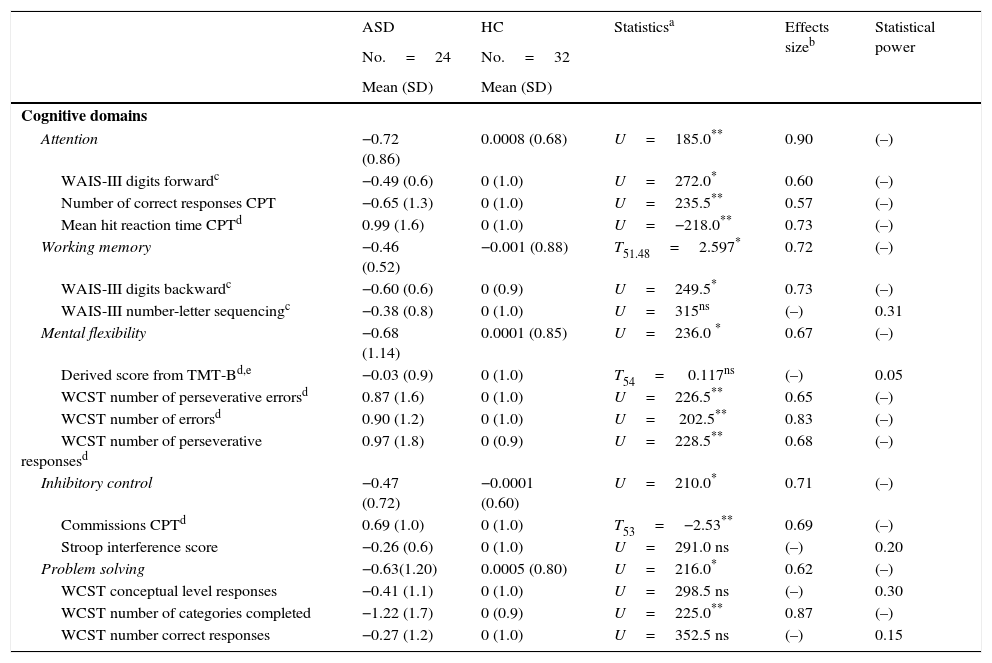

Comparing z-scores between the two groups for the five EF domains assessed (attention, working memory, inhibitory control, mental flexibility, and problem solving) revealed significant differences between patients and controls, with better performance in favor of HC. When we compared the mean z-scores for each individual cognitive measure, we found statistical differences in the following: WAIS-III Digits Forward, CPT correct responses and CPT mean hit reaction time (all measures included Attention domains); WAIS-III Digits Backward (measure included Working Memory domain); WCST number of perseverative errors, WCST number of errors, WCST number of perseverative responses (measures included Mental Flexibility domain); CPT commission errors (measure included Inhibitory Control domain); WCST number of categories completed (measure included Problem Solving domain) (Table 3).

Z-scores on neuropsychological tests for autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability compared with healthy controls.

| ASD | HC | Statisticsa | Effects sizeb | Statistical power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=24 | No.=32 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Cognitive domains | |||||

| Attention | −0.72 (0.86) | 0.0008 (0.68) | U=185.0** | 0.90 | (–) |

| WAIS-III digits forwardc | −0.49 (0.6) | 0 (1.0) | U=272.0* | 0.60 | (–) |

| Number of correct responses CPT | −0.65 (1.3) | 0 (1.0) | U=235.5** | 0.57 | (–) |

| Mean hit reaction time CPTd | 0.99 (1.6) | 0 (1.0) | U=−218.0** | 0.73 | (–) |

| Working memory | −0.46 (0.52) | −0.001 (0.88) | T51.48=2.597* | 0.72 | (–) |

| WAIS-III digits backwardc | −0.60 (0.6) | 0 (0.9) | U=249.5* | 0.73 | (–) |

| WAIS-III number-letter sequencingc | −0.38 (0.8) | 0 (1.0) | U=315ns | (–) | 0.31 |

| Mental flexibility | −0.68 (1.14) | 0.0001 (0.85) | U=236.0 * | 0.67 | (–) |

| Derived score from TMT-Bd,e | −0.03 (0.9) | 0 (1.0) | T54= 0.117ns | (–) | 0.05 |

| WCST number of perseverative errorsd | 0.87 (1.6) | 0 (1.0) | U=226.5** | 0.65 | (–) |

| WCST number of errorsd | 0.90 (1.2) | 0 (1.0) | U= 202.5** | 0.83 | (–) |

| WCST number of perseverative responsesd | 0.97 (1.8) | 0 (0.9) | U=228.5** | 0.68 | (–) |

| Inhibitory control | −0.47 (0.72) | −0.0001 (0.60) | U=210.0* | 0.71 | (–) |

| Commissions CPTd | 0.69 (1.0) | 0 (1.0) | T53=−2.53** | 0.69 | (–) |

| Stroop interference score | −0.26 (0.6) | 0 (1.0) | U=291.0 ns | (–) | 0.20 |

| Problem solving | −0.63(1.20) | 0.0005 (0.80) | U=216.0* | 0.62 | (–) |

| WCST conceptual level responses | −0.41 (1.1) | 0 (1.0) | U=298.5 ns | (–) | 0.30 |

| WCST number of categories completed | −1.22 (1.7) | 0 (0.9) | U=225.0** | 0.87 | (–) |

| WCST number correct responses | −0.27 (1.2) | 0 (1.0) | U=352.5 ns | (–) | 0.15 |

ASD, Autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability; CPT-II, continuous performance test-II; HC, healthy controls; SD, standard deviation; TMT (A–B), trail making test (parts A and B); WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; ns, non-significative.

Statistics: T-Student (T) or Mann–Whitney U test (U) according to statistical characteristics of the variables.

Score used in this study: (time to complete TMT(B)−time to complete TIMT(A))/time to complete TMT(A).

For all neuropsychological measures where we did not find statistical significance between groups (WAIS-III Letter-Number sequencing, TMT-B derived score, Stroop interference score, WCST conceptual level responses, and WCST number of correct responses), we calculated the statistical power and it was not higher than 0.31 (Fig. 1).

We did not find a statistically significant difference in any EF domain between ASD-WID patients with or without treatment (attention: U=63.0, p=0.951; working memory: T22=1.026, p=0.316; mental flexibility: U=61.0, p=0.854; inhibitory control: U=53.0, p=0.501; problem solving: U=59.500, p=0.783).

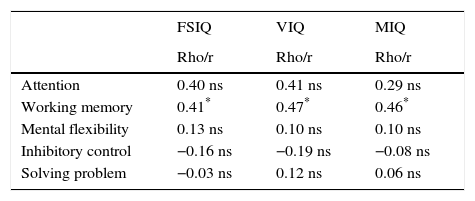

Executive function by IQWithin the ASD group, we did not find statistically significant correlations between FSIQ, VIQ, MIQ, and any of the EF domains assessed except for working memory. More details are shown in Table 4.

Bivariate correlation between intelligence quotients and executive function domains in autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability.

| FSIQ | VIQ | MIQ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rho/r | Rho/r | Rho/r | |

| Attention | 0.40 ns | 0.41 ns | 0.29 ns |

| Working memory | 0.41* | 0.47* | 0.46* |

| Mental flexibility | 0.13 ns | 0.10 ns | 0.10 ns |

| Inhibitory control | −0.16 ns | −0.19 ns | −0.08 ns |

| Solving problem | −0.03 ns | 0.12 ns | 0.06 ns |

FSIQ, full scale intelligence quotient (WAIS-III or WISC-R); MIQ, manipulative intelligence quotient; VIQ, verbal intelligence quotient; ns, non-significative.

Statistics: Pearson (r) or Spearman (Rho) according to statistical characteristics of the variables.

The differences in the EF domains after controlling for IQ were still significant: attention (F(1)=7.495, p=0.007, D=0.13), working memory (F(1)=4.452; p=0.04; D=0.07), mental flexibility (F(1)=4.804; p=0.03 D=0.08), inhibitory control (F(1)=6.638; p=0.013; D=0.11), and problem solving (F(1)=5.247; p=0.02; D=0.09).

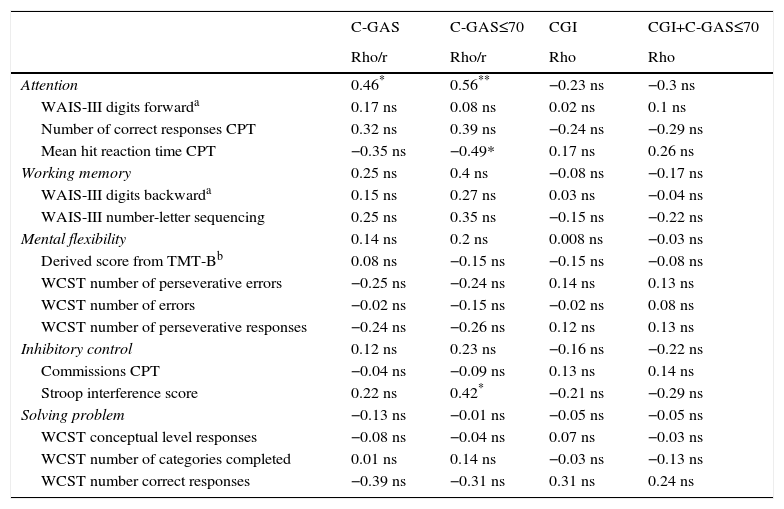

Executive function and adaptive functioningOnly the attention domain scores clearly correlate with daily life functioning as measured by the C-GAS. None of the EF domains correlates with severity (CGI). More details are shown in Table 5.

Bivariate correlation between neuropsychological and clinical variables in autism spectrum disorders.

| C-GAS | C-GAS≤70 | CGI | CGI+C-GAS≤70 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rho/r | Rho/r | Rho | Rho | |

| Attention | 0.46* | 0.56** | −0.23 ns | −0.3 ns |

| WAIS-III digits forwarda | 0.17 ns | 0.08 ns | 0.02 ns | 0.1 ns |

| Number of correct responses CPT | 0.32 ns | 0.39 ns | −0.24 ns | −0.29 ns |

| Mean hit reaction time CPT | −0.35 ns | −0.49* | 0.17 ns | 0.26 ns |

| Working memory | 0.25 ns | 0.4 ns | −0.08 ns | −0.17 ns |

| WAIS-III digits backwarda | 0.15 ns | 0.27 ns | 0.03 ns | −0.04 ns |

| WAIS-III number-letter sequencing | 0.25 ns | 0.35 ns | −0.15 ns | −0.22 ns |

| Mental flexibility | 0.14 ns | 0.2 ns | 0.008 ns | −0.03 ns |

| Derived score from TMT-Bb | 0.08 ns | −0.15 ns | −0.15 ns | −0.08 ns |

| WCST number of perseverative errors | −0.25 ns | −0.24 ns | 0.14 ns | 0.13 ns |

| WCST number of errors | −0.02 ns | −0.15 ns | −0.02 ns | 0.08 ns |

| WCST number of perseverative responses | −0.24 ns | −0.26 ns | 0.12 ns | 0.13 ns |

| Inhibitory control | 0.12 ns | 0.23 ns | −0.16 ns | −0.22 ns |

| Commissions CPT | −0.04 ns | −0.09 ns | 0.13 ns | 0.14 ns |

| Stroop interference score | 0.22 ns | 0.42* | −0.21 ns | −0.29 ns |

| Solving problem | −0.13 ns | −0.01 ns | −0.05 ns | −0.05 ns |

| WCST conceptual level responses | −0.08 ns | −0.04 ns | 0.07 ns | −0.03 ns |

| WCST number of categories completed | 0.01 ns | 0.14 ns | −0.03 ns | −0.13 ns |

| WCST number correct responses | −0.39 ns | −0.31 ns | 0.31 ns | 0.24 ns |

ASD, Autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability; C-GAS, children's global assessment of functioning; CGI, Clinical Global Impression Scale; CGI+C-GAS≤70, CGI scores in patients with C-GAS≤70; CPT-II, continuous performance test-II; SD, standard deviation; TMT (A–B), trail making test (parts A and B); WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; ns, non-significative.

Our results show that children and adolescents with ASD-WID have impaired EF. Despite having a normal full IQ, the cognitive profile of our sample is characterized by significant deficits in the five EF domains assessed (attention, working memory, flexibility, inhibitory control, and problem solving). Moreover, the EF results do not correlate with IQ in this sample of ASD patients.

During the past three decades, numerous studies support an executive impairment in autism.47–56 However, most studies have reported a more limited evaluation of executive functioning. Firstly, in the attention domain, our results suggest difficulties in sustained and selective attention tasks, and longer response latency in ASD. Similar problems have been shown in the literature.1–3,57 Kilinçaslan et al. did not find differences between the ASD and control groups in a sustained attention task, but did when the ASD group had a comorbid ADHD.4 It is remarkable that, although none of our patients had a comorbid ADHD disorder, they probably had some subthreshold attention symptoms, as previous research has demonstrated.58 In fact, given the importance of attention for academic performance, for planning of intervention programs, attention difficulties should be taken into account in child/adolescent ASD populations, even when they do not have a comorbid ADHD diagnosis.

Secondly, problems with inhibition of automatic responses were found in our study, in line with previous studies.3–5,7,8,13,15,18 This deficit shows that ASD patients have difficulties inhibiting prepotent responses, implying longer times to process information and perform tasks. This result is in line with previous studies in ASD patients, studies that demonstrate processing speed problems across the lifespan in individuals with ASD.59–63 Slower processing speeds have been associated with severe communication symptoms in high functioning children with ASD61 and were found to be predictive of educational achievements in math, reading, and writing.64

Problems with mental flexibility have also previously been reported,4,7,8,15,17,65 with some exceptions, as in Kaland et al., who used a computerized version of the WCST2 to assess mental flexibility in ASD patients. Their results are in line with some studies that had reported better performance with this computerized task in ASD patients.16,66 Poor cognitive flexibility is manifested by perseverative and stereotyped behavior and difficulties in the regulation and modulation of motor acts.48 In fact, although correlations between repetitive behavior, insistence on sameness, and cognitive perseveration have not been clearly established, insistence on sameness is a characteristic that has been included in the core symptoms of autism by some of the most preeminent authors.67–69 In the recently published DSM 5,70 fulfillment of a B criterion that comprises insistence on sameness together with other repetitive or stereotyped behaviors and/or sensory anomalies is mandatory for a diagnosis of ASD.

Furthermore, the deficits in verbal working memory reported in our study are in line with previous studies in the literature that indicate that ASD patients have difficulty retaining and manipulating verbal and visual information.7–9,13–16 Cui et al. assessed and compared verbal and working memory and found children with ASD had better performance in verbal working memory and worse performance in visual working memory tasks, suggesting a possible imbalance of working memory development in ASD children.12 Taking into account these results and Baddeley's model71 of working memory, our data does not help us understand whether patients have a central executive problem that in turn affects both phonological and visuospatial processing, or whether these abnormalities are independent.

Likewise, our ASD patients had difficulty with the problem-solving domain. Along the same lines, Troyb et al. found that HFA were less efficient in planning and problem-solving tasks.72 Some authors explain this impairment as the consequence of deficient global processing in autism.73–75

These results show that ASD-WID patients have important executive dysfunctions. We have also shown that EF dysfunctions do not correlate with IQ in our sample of children and adolescents with ASD. The possible correlation of EF with IQ in ASD patients is under debate.7,76–78 We have previously shown that IQ profiles assessed with the WAIS-III and the WISC-R follow a similar distribution,33 although patients who were administered the WAIS-III obtained a larger number of subtests scores falling below the normal range. In our sample, we found only a positive correlation between intelligence measures and working memory, suggesting higher intelligence scores correlated with better performance in the working memory domain. This result should be interpreted with caution because in our study, the working memory domain was composed of two subtests included in the IQ measures (WAIS-III Digits Backward and WAIS-III Letter-Number Sequencing), which may explain the correlation found. It would be necessary to study this relationship with other working memory tasks in order to confirm or refute the results obtained in our study. Moreover, when ASD-WID patients are compared with HC controlling for IQ, we also found statistically significantly worse performance in the ASD group. In the same vein as our results, in an ASD sample compared with a non-IQ-matched control group, Narzisi et al. found that deficits in EF were still significant after removing the effects of verbal IQ and that neuropsychological linguistic abilities favor a primary dysfunction of EF in ASD-WID.7 In their study, they used the NEPSY-II battery79 to explore the neuropsychological profile in ASD-WID, which includes EF. Although we used a different neuropsychological battery to assess EF in ASD-WID, our results were similar in all domains, even when compared with groups well matched for IQ, as in our study.

A recommendation derived from these results is that comprehensive executive functioning assessments should be conducted as part of the global assessment in ASD patients, as in other psychiatric pathologies,80 especially for the purpose of designing interventions, as measurement of global intelligence is not enough to give an idea of the patient's cognitive abilities. The recent classification of mental disorders (DSM-5) allows for clinical specifiers to be added to the diagnosis of ASD in order to give a more comprehensive picture of the patient clinical profile and to guide interventions. We would argue that an evaluation of executive functioning should be part of the basic comprehensive evaluation for therapeutic purposes; having only data on general cognitive functioning may overestimate the capacity of ASD subjects. A neuropsychological assessment of EF should include the cognitive domains of attention, working memory (verbal and visual–spatial), inhibitory control, mental flexibility, planning, and problem solving. To ensure that global processing abilities do not interfere with specific EF performance, the specific tasks should be selected according to level of cognitive complexity, considering that some authors have found ASD-WID patients have deficits specifically associated with increasing cognitive load,77,81–84 along with selected computerized tasks, as studies have indicated that ASD patients perform better on computerized tasks.16,66 Our results show no correlation with adaptive functioning or severity as measured by CGAS and CGI. However, these are not subtle measures of academic or vocational performance, very important aspects of long-term prognosis. Therefore, from a clinical perspective, it would be interesting to explore how performance on executive functioning tests correlates with executive functioning questionnaires in reported real life by parents and teachers, such as the behavior rating inventory of EF (BRIEF),85 or with other measures of real-life performance.

Given that ASD are usually diagnosed during childhood development, changes in EF impairment according to age should be considered in treatment plans.7,15,86 Along this line, studies have found age-related differences in working memory, organization, and initiation,86 inhibition, planning, and flexibility86 in children and adolescents with ASD according to parent reports.

The results of the present study should be interpreted with caution due to some methodological limitations. Firstly, the sample size of ASD-WID patients was small. However, we found statistically significant differences among principal study variables (EF domains). Secondly, we used the table version of the WCST, and studies indicate that ASD patients perform better on the WCST using the computer version.16,66 Thirdly, although the cognitive assessment was performed using an extensive EF battery, we did not evaluate visual and spatial working memory, or phonological or semantic fluency. The strengths of this study include an exhaustive assessment of an extensive range of EF domains in a well matched, homogeneous sample of patients with ASD-WID and HC. These five domains were evaluated with a comprehensive neuropsychological battery composed of different tests specifically designed for evaluation of EF.

Future studies should consider examining executive dysfunction in TEA patients who also present with a psychiatric comorbidity.

In conclusion, children and adolescents with ASD-WID have difficulty retaining and mentally manipulating verbal information, longer response latency, attention shifting problems, lack of inhibition of automatic responses, and problem-solving difficulties, despite having a normal IQ. Considering the low EF profile found in our group, we suggest a comprehensive intervention including complementary rehabilitation programs in the non-social domains.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors must have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence must be in possession of this document.

FundingThis work was carried out with the support of Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Institute of Salud Carlos III, CIBERSAM, the Community of Madrid (Supports R&D office in Biomedi-S2010/BMD-2422 AGES) and Structural Funds of the European Union, the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation, la Fundación Mutua Madrileña and ERA-NET NEURON (Network of European Funding for Neuroscience Research) Foundation.

Conflict of interestJessica Merchán-Naranjo declares no conflict of interest.

Leticia Boada declares no conflict of interest.

Ángel King-Mejias declares no conflict of interest.

María Mayoral has received a research grant from Madrid (predoctoral fellowship) Institute of Carlos III and Health and the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness.

Cloe Llorente declares no conflict of interest.

Celso Arango has been a consultant and has received fees or grants from Abbot, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-MyersSquibb, Caja Navarra, CIBERSAM, Alicia Koplowitz Foundation, Institute of Carlos III, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Merck, Ministry of Science and Innovation, Ministry of Sanidad, Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Mutua Madrileña, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Shire, Schering-Plough and Takeda.

Parellada Mara has received grants for training and travel of the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation and Otsuka.

Thanks to the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Carlos III Health Institute, CIBERSAM, Madrid and Structural Funds of the European Union, Alicia Koplowitz Foundation and Mutua Madrileña Foundation and ERA-NET NEURON (Network of European Funding for Neuroscience Research).

Please cite this article as: Merchán-Naranjo J, Boada L, del Rey-Mejías Á, Mayoral M, Llorente C, Arango C, et al. La función ejecutiva está alterada en los trastornos del espectro autista, pero esta no correlaciona con la inteligencia. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2016;9:39–50.