There has been a considerable proliferation of clinical guidelines recently, but their practical application is low, and organisations do not always implement their own ones. The aim of this study is to analyse and describe key elements of strategies and resources designed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for the implementation of guidelines for common mental health disorders in adults, which are some of the most prevalent worldwide.

MethodA systematic review was performed following PRISMA model. Resources, tools and implementation materials were included and categorised considering type, objectives, target and scope.

ResultsA total of 212 elements were analysed, of which 33.5% and 24.5% are related to the implementation of generalised anxiety and depression guidelines, respectively. Applied tools designed to estimate costs and assess the feasibility of the setting up at local level are the most frequent type of resource. The study highlights the important variety of available materials, classified into 3 main strategies: tools targeting the professionals (30.6%), structural (26.4%), and organisational (24%).

ConclusionsDeveloping guidelines is not enough; it is also necessary to promote their implementation in order to encourage their application. The resources and strategies described in this study may be potentially applicable to other contexts, and helpful to public health managers and professionals in the design of programmes and in the process of informed decision making to help increase access to efficient treatments.

Pese a que la producción de guías clínicas ha proliferado considerablemente, su aplicación en la práctica es baja y muchos organismos no implementan las guías que producen. El objetivo de este estudio es sintetizar y describir elementos clave de las estrategias y recursos diseñados por el National Institute for Health and Care Excellence para la implementación de guías de trastornos comunes de salud mental en adultos, uno de los problemas más prevalentes a escala mundial.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio de revisión y compilación de recursos de implementación siguiendo el modelo PRISMA. Se localizaron y clasificaron herramientas y materiales con base en la taxonomía propuesta por el grupo EPOC de la Cochrane.

ResultadosSe analizaron 212 elementos que se asocian a la implantación de guías de ansiedad generalizada y depresión (33,5 y 24,5%, respectivamente). Destaca la importante variedad de materiales disponibles, integrados en 3 estrategias fundamentales: intervenciones dirigidas a los profesionales (30,6%), estructurales (26,4%) y organizativas (24%). Las herramientas aplicadas son el tipo de recurso más frecuente, que permiten valorar la viabilidad de la puesta en marcha a nivel local.

ConclusionesLa elaboración de guías no es suficiente para que se produzca su aplicación en la práctica. Es necesario que se lleven a cabo acciones que favorezcan su implementación. Los recursos y estrategias descritos podrían ser potencialmente aplicables a otros contextos y orientar a gestores y profesionales en el diseño de programas y en la toma de decisiones informadas, para mejorar el acceso a tratamientos eficaces en los sistemas públicos de salud.

Mental health problems constitute 5 of the 10 main causes of morbidity and disability worldwide, with important personal, social and economic costs for the individuals suffering from them.1,2 Among these, what are called common mental health disorders (CMHD), mainly anxiety and depression, are extremely prevalent in adults.3,4 This is the second most important factor linked to disability-adjusted life years globally.5

Public healthcare services need to address the important burden that these disorders represent to be able to handle healthcare requirements. This is true at both the entry treatment level and in specialised services. Many studies have assessed the efficacy of various drug and non-drug treatments to establish which intervention or combination of treatments yield the most effective approach to this problem. Because of this, evidence-based mental health models have been adopted to make providing services better.6–8 This has increased the production of clinical practice guidelines (CPG) in various sectors, from academic or research to official organisms and healthcare systems.9

The proliferation of guidelines could be considered to be a substantial advance along the path to improving care of mental health problems. However, considerable deficits still remain in making effective treatments accessible to everyone, given that (as the literature reflects) complying to and using the recommendations is limited in normal professional practice. In addition, it is recognised that the organisms and systems themselves do not take adequate steps to implement the guidelines that they themselves produce.10,11 As a result of these deficiencies in the implementation processes, there are few systems that incorporate and apply CPGs effectively in their services.

Various studies9,12 emphasise the existence of multiple barriers affecting guideline implementation. Examples of these obstacles are the professionals’ lack of confidence in guideline quality, organisational factors, the fact that both professionals and decision-making individuals lack training or knowledge, user expectations and excessive complication in guideline presentation. These aspects widen the gap between the research generating the recommendations and the professionals’ daily activities. In response to this situation, initiatives to improve implementation processes are beginning to appear, such as the adaptation to more accessible formats, reminder or support systems for decision-making, access to professional training modules and the design of evaluation programmes, among others.9,13 However, the studies on implementation models or strategies are limited, there is little formal or systematic research on applying guidelines and even less aimed at increasing knowledge about the processes of implementing clinical guidelines in the mental health setting.14–17

One of the key organisms for CPG production is the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).18 In addition to developing evidence-based recommendations, this organism offers a set of resources and tools to promote the practical implementation of the guidelines that it produces, both in general health and in mental health. Although these strategies possess achievements and limitations,11,19,20 they could constitute a model potentially applicable to other realities.

The objective of our study was to synthesise, quantify and describe the key features of the NICE-designed resources for implementing CPGs for adult CMHD treatment. Our intention was to improve the understanding of the strategies underlying guideline implementation.

MethodWe carried out a study for review and compilation of implementation resources, following several recommendations and key criteria of the Preferred Reporting Items of systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) declaration.21,22 Tools, materials and documents related to the establishment of clinical CMHD guidelines prepared by NICE were reviewed. Table 1 shows the list of guidelines23–29 included in this study and all the resources associated with each of them.

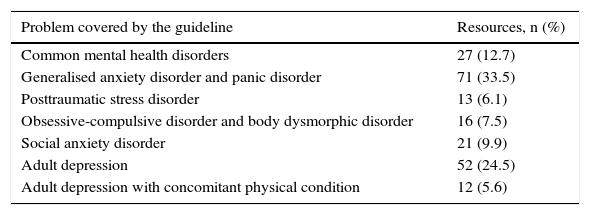

Total number and percentage of implementation resources associated with each clinical guideline.

| Problem covered by the guideline | Resources, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Common mental health disorders | 27 (12.7) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder | 71 (33.5) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 13 (6.1) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder | 16 (7.5) |

| Social anxiety disorder | 21 (9.9) |

| Adult depression | 52 (24.5) |

| Adult depression with concomitant physical condition | 12 (5.6) |

The official NICE was examined in detail. Once each clinical guideline had been identified, we opened the Tools and Resources section, which contained subsections with links to documents, materials and resources prepared or selected for implementing each of the guidelines that we intended to study.

When all of the elements were located, we eliminated the duplicates and applied the eligibility criteria.

Eligibility criteriaIncluded in this study were: (a) all resources aimed at managers, professionals, users or general public (directly or indirectly related to the implementation/establishment of adult clinical CMHD guidelines), and (b) various types of resources: clinical guidelines, scientific articles, reports, guidebooks, tools, online resources, audiovisual material and training material.

We excluded all resources that were: (a) unrelated to CMHD, (b) unrelated to implementation, (c) associated with purely legislatives or regulatory matters, or (d) aimed at children/adolescents.

Data extractionStep 1. All the elements identified were entered into a database designed to organise the following general information general: title, year of publication, language (English, Welsh, other), format (Word, Excel, PDF, PPT, audio, video, other), pages/length and references.

Step 2. All the resources fulfilling the eligibility criteria were analysed in depth based on a series of ad-hoc categories and subcategories designed on the basis of some key criteria from the taxonomies proposed in reference studies.9,13,15 These served for the extraction of specific data for each one (such as type of material, objectives, target population and scope of applicability) and for assistance in deciding about data regrouping in the following step.

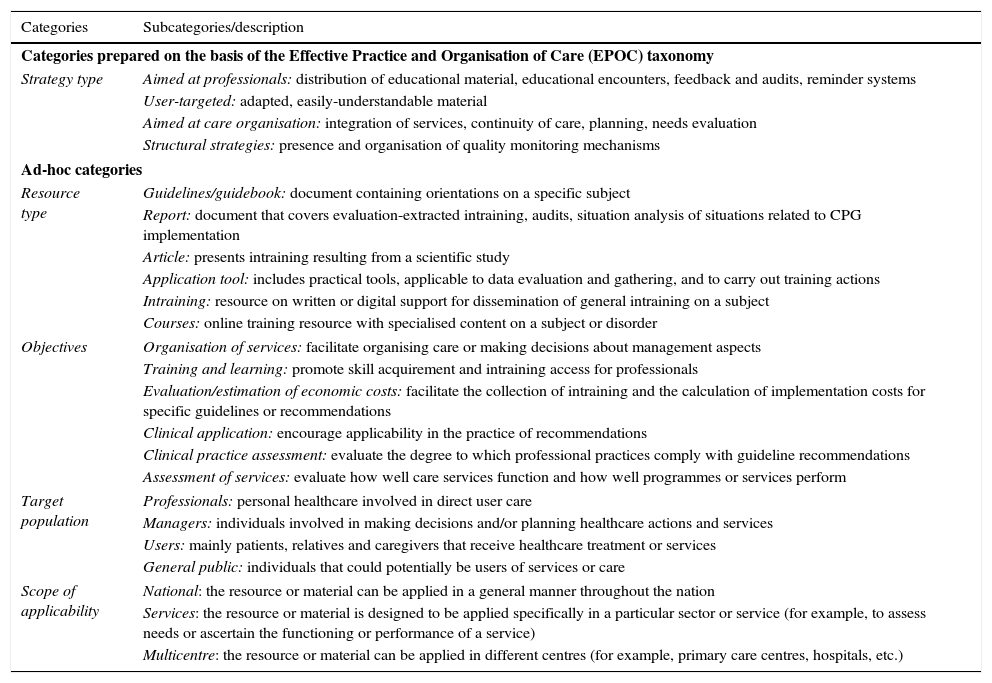

Step 3. Once the characteristics of each resource had been examined, we regrouped them in the categories of analysis defined on the basis of the taxonomy proposed by the collaborative Cochrane group Effective Practice and Organisation of Care.11,30–32 This taxonomy makes it possible to analyse a series of action steps and strategies to change clinical practices. The categories used in Steps 2 and 3, for analysing the materials included in this study, are listed and described in Table 2.

Description of the categories and subcategories selected and designated for data extraction and analysis.

| Categories | Subcategories/description |

|---|---|

| Categories prepared on the basis of the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy | |

| Strategy type | Aimed at professionals: distribution of educational material, educational encounters, feedback and audits, reminder systems |

| User-targeted: adapted, easily-understandable material | |

| Aimed at care organisation: integration of services, continuity of care, planning, needs evaluation | |

| Structural strategies: presence and organisation of quality monitoring mechanisms | |

| Ad-hoc categories | |

| Resource type | Guidelines/guidebook: document containing orientations on a specific subject |

| Report: document that covers evaluation-extracted intraining, audits, situation analysis of situations related to CPG implementation | |

| Article: presents intraining resulting from a scientific study | |

| Application tool: includes practical tools, applicable to data evaluation and gathering, and to carry out training actions | |

| Intraining: resource on written or digital support for dissemination of general intraining on a subject | |

| Courses: online training resource with specialised content on a subject or disorder | |

| Objectives | Organisation of services: facilitate organising care or making decisions about management aspects |

| Training and learning: promote skill acquirement and intraining access for professionals | |

| Evaluation/estimation of economic costs: facilitate the collection of intraining and the calculation of implementation costs for specific guidelines or recommendations | |

| Clinical application: encourage applicability in the practice of recommendations | |

| Clinical practice assessment: evaluate the degree to which professional practices comply with guideline recommendations | |

| Assessment of services: evaluate how well care services function and how well programmes or services perform | |

| Target population | Professionals: personal healthcare involved in direct user care |

| Managers: individuals involved in making decisions and/or planning healthcare actions and services | |

| Users: mainly patients, relatives and caregivers that receive healthcare treatment or services | |

| General public: individuals that could potentially be users of services or care | |

| Scope of applicability | National: the resource or material can be applied in a general manner throughout the nation |

| Services: the resource or material is designed to be applied specifically in a particular sector or service (for example, to assess needs or ascertain the functioning or performance of a service) | |

| Multicentre: the resource or material can be applied in different centres (for example, primary care centres, hospitals, etc.) | |

To facilitate data extraction and analysis, we prepared a checklist control system. Doubts as to the categorisation of an element were resolved by consensus with a healthcare management expert, uninvolved with the research.

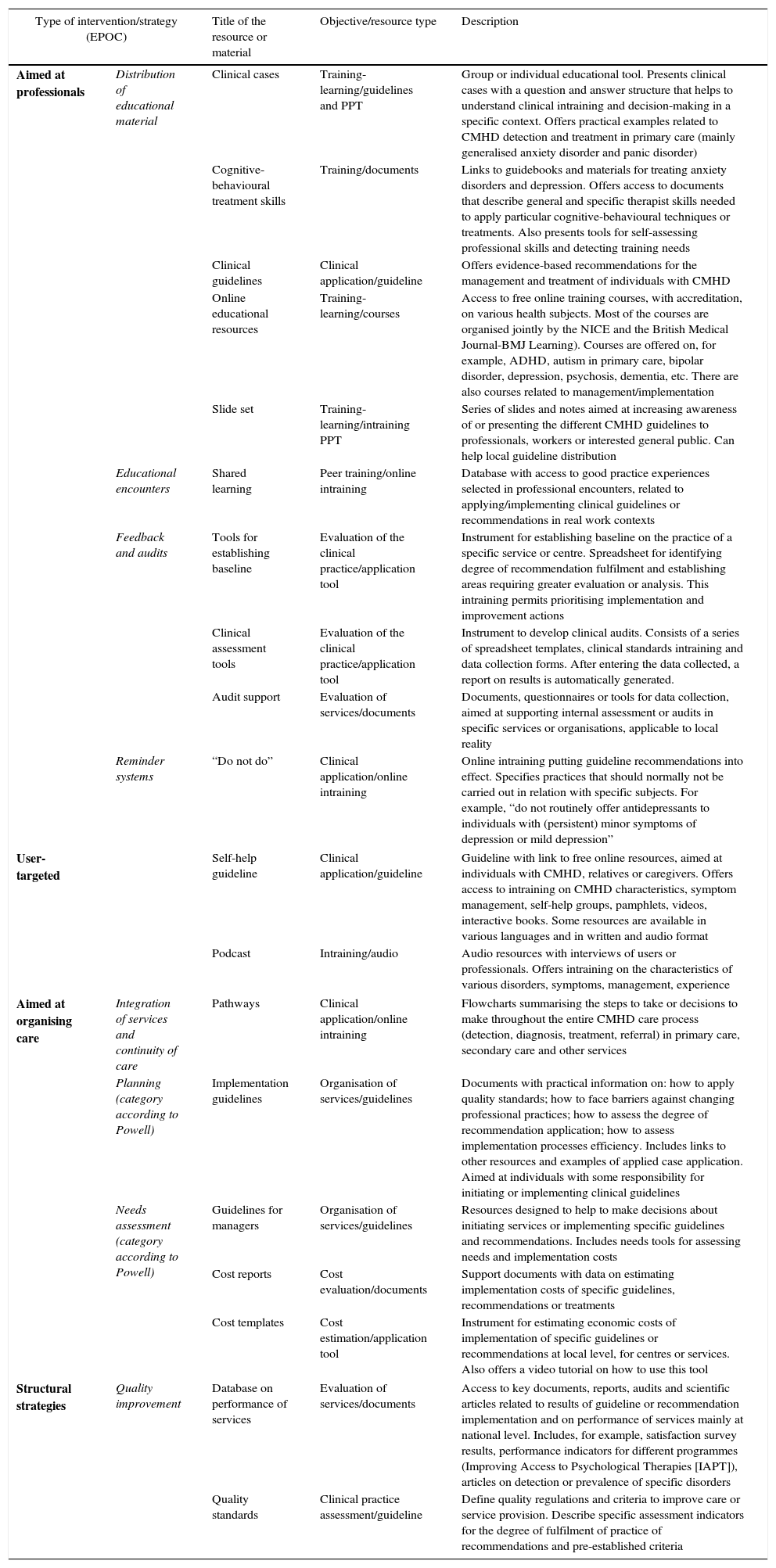

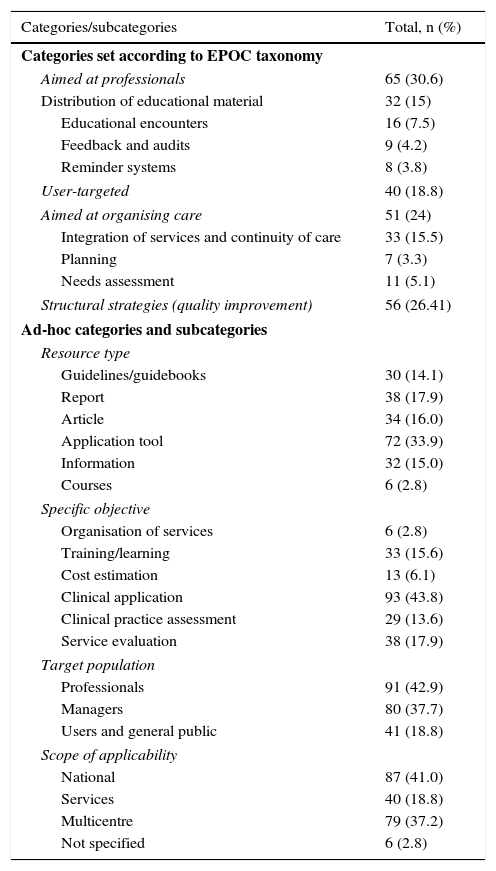

Finally, we carried out a qualitative and quantitative descriptive analysis that included measures of frequency and percentages. Table 3 shows a qualitative synthesis of the characteristics of the main resources included in this study, organised by the most relevant categories of analysis.

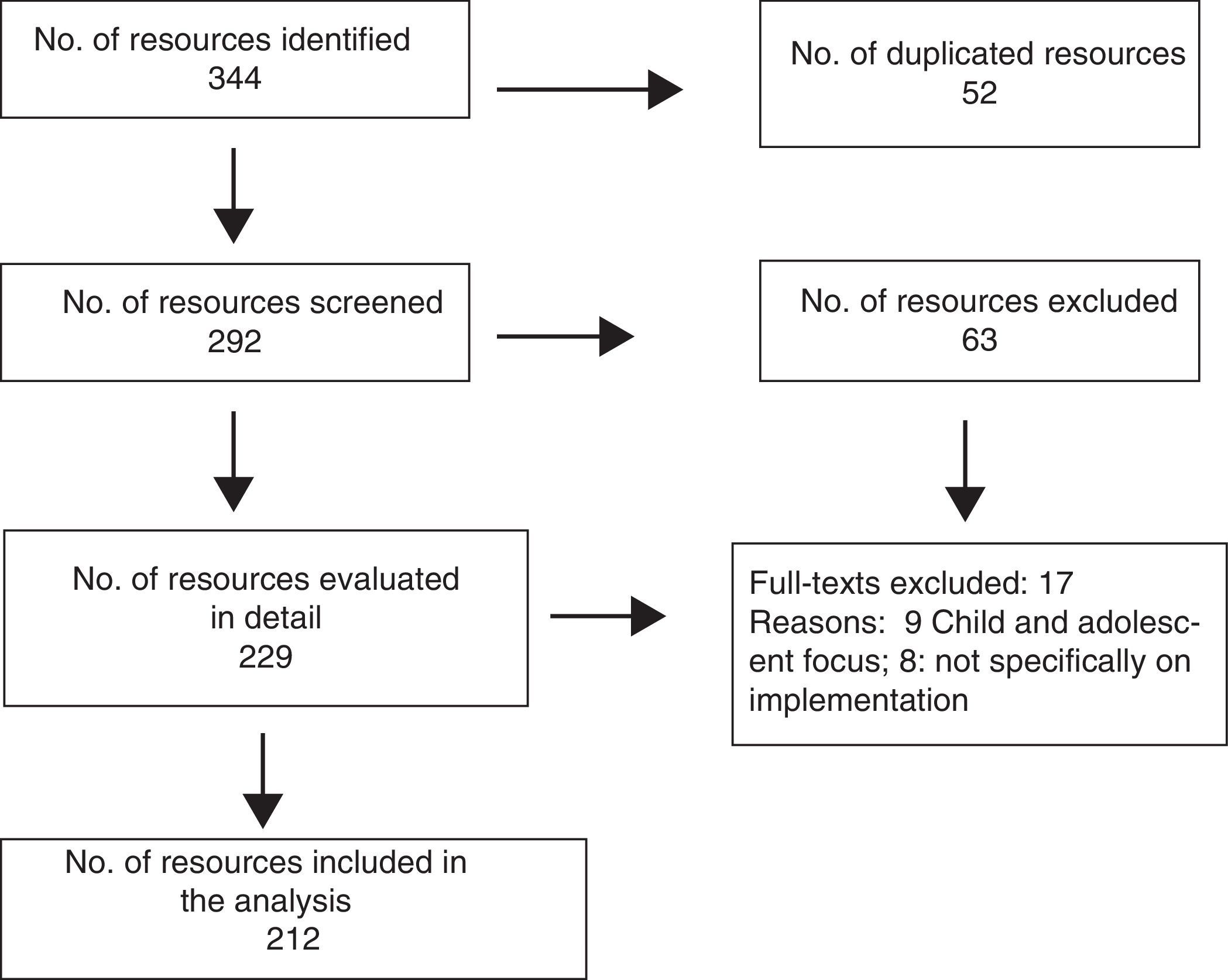

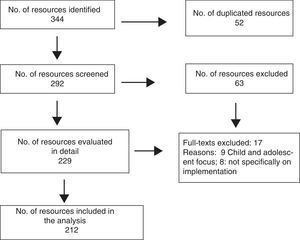

ResultsSelection processFig. 1 shows the selection process. Initially, 344 resources were identified; after eliminating the duplicate entries, 292 elements remained, which were evaluated taking the titles and abstracts into consideration. This first screening eliminated 63 documents that did not fulfil the inclusion criteria. Next, the 229 remaining resources were evaluated in depth, excluding from these 17 for the following reasons: (1) being aimed at children or adolescents, and (2) being unrelated either directly or indirectly to implementing the CMHD guidelines. In the end, 212 resources were included in the analysis.

General characteristicsOf the total of 212 elements analysed, we found that the guidelines with the most associated implementation resources were, in first place, those on generalised anxiety disorder (with 71 resources), followed by 52 resources related to depression guidelines. The guidelines with the fewest implementation resources were those on social anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic distress and depression with concomitant physical conditions (see Table 1).

Considering the classification by resource type, the most frequent were the application tools, which constituted almost 34% of the total. They included eminently practical tools applied for data assessment and collection (such as cost spreadsheet templates or questionnaires) or training tools (for example, slide sets). In second place were reports, which constituted almost 18%, followed by articles (16%). Examples of the latter would be the results of reports on provision of services, clinical audit results and cost reports, among others. Access to information and implementation guidebooks or guidelines represented similar proportions, between 15% and 14%, respectively, while courses were found significantly less frequently.

As for the scope of applicability, the most frequent was national (41%) (including materials such as guidelines, recommendations and statistical or cost reports/articles). Of the elements found, 37.2% could be applied at multicentre level; 18.8% were designed to be applied more specifically to level of services (for example, materials for carrying out clinical audits).

With respect to implementation strategies (see Tables 3 and 4), the most notable were those aimed at professionals, which contained 30.6% of the available material. In this segment, we found resources focused on promoting training and learning through the design and diffusion of educational material and access to peer information about good practice experiences; they represented 26.4% of the resources in all. There were also tools and documents for carrying out professional practice assessment at the local level and performing clinical audits, as well as reminder systems, which constituted 4.2% and 3.8%, respectively.

Classification and qualitative description of the implementation resources included in the study.

| Type of intervention/strategy (EPOC) | Title of the resource or material | Objective/resource type | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aimed at professionals | Distribution of educational material | Clinical cases | Training-learning/guidelines and PPT | Group or individual educational tool. Presents clinical cases with a question and answer structure that helps to understand clinical intraining and decision-making in a specific context. Offers practical examples related to CMHD detection and treatment in primary care (mainly generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder) |

| Cognitive-behavioural treatment skills | Training/documents | Links to guidebooks and materials for treating anxiety disorders and depression. Offers access to documents that describe general and specific therapist skills needed to apply particular cognitive-behavioural techniques or treatments. Also presents tools for self-assessing professional skills and detecting training needs | ||

| Clinical guidelines | Clinical application/guideline | Offers evidence-based recommendations for the management and treatment of individuals with CMHD | ||

| Online educational resources | Training-learning/courses | Access to free online training courses, with accreditation, on various health subjects. Most of the courses are organised jointly by the NICE and the British Medical Journal-BMJ Learning). Courses are offered on, for example, ADHD, autism in primary care, bipolar disorder, depression, psychosis, dementia, etc. There are also courses related to management/implementation | ||

| Slide set | Training-learning/intraining PPT | Series of slides and notes aimed at increasing awareness of or presenting the different CMHD guidelines to professionals, workers or interested general public. Can help local guideline distribution | ||

| Educational encounters | Shared learning | Peer training/online intraining | Database with access to good practice experiences selected in professional encounters, related to applying/implementing clinical guidelines or recommendations in real work contexts | |

| Feedback and audits | Tools for establishing baseline | Evaluation of the clinical practice/application tool | Instrument for establishing baseline on the practice of a specific service or centre. Spreadsheet for identifying degree of recommendation fulfilment and establishing areas requiring greater evaluation or analysis. This intraining permits prioritising implementation and improvement actions | |

| Clinical assessment tools | Evaluation of the clinical practice/application tool | Instrument to develop clinical audits. Consists of a series of spreadsheet templates, clinical standards intraining and data collection forms. After entering the data collected, a report on results is automatically generated. | ||

| Audit support | Evaluation of services/documents | Documents, questionnaires or tools for data collection, aimed at supporting internal assessment or audits in specific services or organisations, applicable to local reality | ||

| Reminder systems | “Do not do” | Clinical application/online intraining | Online intraining putting guideline recommendations into effect. Specifies practices that should normally not be carried out in relation with specific subjects. For example, “do not routinely offer antidepressants to individuals with (persistent) minor symptoms of depression or mild depression” | |

| User-targeted | Self-help guideline | Clinical application/guideline | Guideline with link to free online resources, aimed at individuals with CMHD, relatives or caregivers. Offers access to intraining on CMHD characteristics, symptom management, self-help groups, pamphlets, videos, interactive books. Some resources are available in various languages and in written and audio format | |

| Podcast | Intraining/audio | Audio resources with interviews of users or professionals. Offers intraining on the characteristics of various disorders, symptoms, management, experience | ||

| Aimed at organising care | Integration of services and continuity of care | Pathways | Clinical application/online intraining | Flowcharts summarising the steps to take or decisions to make throughout the entire CMHD care process (detection, diagnosis, treatment, referral) in primary care, secondary care and other services |

| Planning (category according to Powell) | Implementation guidelines | Organisation of services/guidelines | Documents with practical information on: how to apply quality standards; how to face barriers against changing professional practices; how to assess the degree of recommendation application; how to assess implementation processes efficiency. Includes links to other resources and examples of applied case application. Aimed at individuals with some responsibility for initiating or implementing clinical guidelines | |

| Needs assessment (category according to Powell) | Guidelines for managers | Organisation of services/guidelines | Resources designed to help to make decisions about initiating services or implementing specific guidelines and recommendations. Includes needs tools for assessing needs and implementation costs | |

| Cost reports | Cost evaluation/documents | Support documents with data on estimating implementation costs of specific guidelines, recommendations or treatments | ||

| Cost templates | Cost estimation/application tool | Instrument for estimating economic costs of implementation of specific guidelines or recommendations at local level, for centres or services. Also offers a video tutorial on how to use this tool | ||

| Structural strategies | Quality improvement | Database on performance of services | Evaluation of services/documents | Access to key documents, reports, audits and scientific articles related to results of guideline or recommendation implementation and on performance of services mainly at national level. Includes, for example, satisfaction survey results, performance indicators for different programmes (Improving Access to Psychological Therapies [IAPT]), articles on detection or prevalence of specific disorders |

| Quality standards | Clinical practice assessment/guideline | Define quality regulations and criteria to improve care or service provision. Describe specific assessment indicators for the degree of fulfilment of practice of recommendations and pre-established criteria | ||

Quantitative results if the 212 implementation resources classified and included in the analysis.

| Categories/subcategories | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Categories set according to EPOC taxonomy | |

| Aimed at professionals | 65 (30.6) |

| Distribution of educational material | 32 (15) |

| Educational encounters | 16 (7.5) |

| Feedback and audits | 9 (4.2) |

| Reminder systems | 8 (3.8) |

| User-targeted | 40 (18.8) |

| Aimed at organising care | 51 (24) |

| Integration of services and continuity of care | 33 (15.5) |

| Planning | 7 (3.3) |

| Needs assessment | 11 (5.1) |

| Structural strategies (quality improvement) | 56 (26.41) |

| Ad-hoc categories and subcategories | |

| Resource type | |

| Guidelines/guidebooks | 30 (14.1) |

| Report | 38 (17.9) |

| Article | 34 (16.0) |

| Application tool | 72 (33.9) |

| Information | 32 (15.0) |

| Courses | 6 (2.8) |

| Specific objective | |

| Organisation of services | 6 (2.8) |

| Training/learning | 33 (15.6) |

| Cost estimation | 13 (6.1) |

| Clinical application | 93 (43.8) |

| Clinical practice assessment | 29 (13.6) |

| Service evaluation | 38 (17.9) |

| Target population | |

| Professionals | 91 (42.9) |

| Managers | 80 (37.7) |

| Users and general public | 41 (18.8) |

| Scope of applicability | |

| National | 87 (41.0) |

| Services | 40 (18.8) |

| Multicentre | 79 (37.2) |

| Not specified | 6 (2.8) |

In second place, we identified materials associated with 2 key strategies: structural (26.4%) and organisational (24%) interventions. For structural interventions, we found resources such as database access and quality standards. As for the organisation of patient care, 1 of the main elements designed to facilitate integration and continuity were care pathways, which represented 15.5%. We also found 5.1% of tools and reports for cost estimation, and 3.3% of resources focused on improving planning actions by designing manager-specific guidelines.

The strategy with the least implementation resources associated was the user-focused, which included only 18.8% of the materials available.

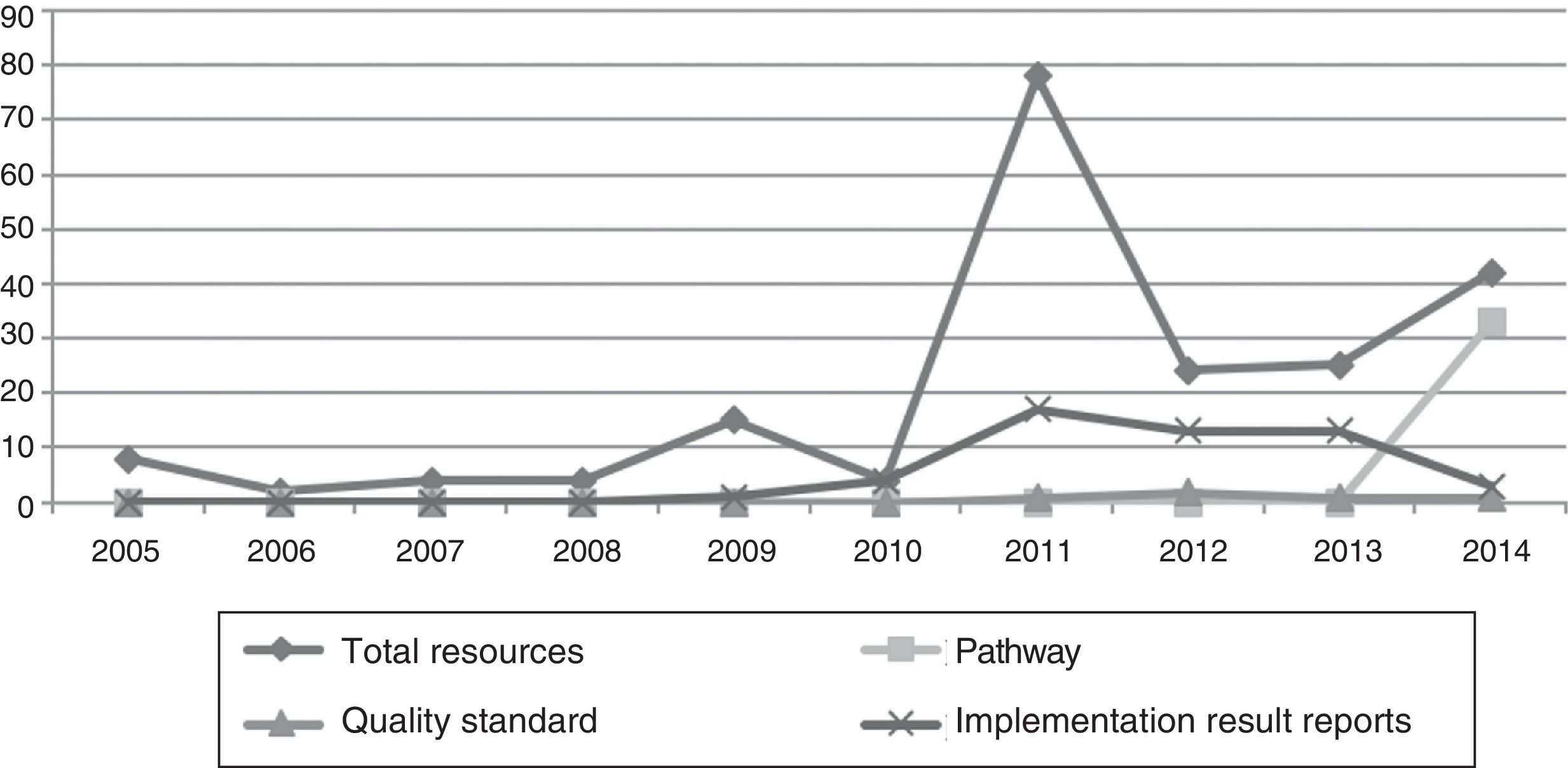

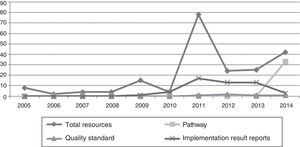

Development over time in the publication of resourcesFig. 2 shows the trend over time in the implementation resource production and publication from 2005 (when the publication of currently existing resources began) to 2014 (time of the review). Significant differences were found in the amount of material published over this period. There were 3 key moments: an initial period, from 2005 to 2010; an increase in resource publication in 2011; and a third period, from 2012 to 2014. The least production occurred during this first period, with a mean of 6.1 resources published per year and a minimum–maximum range of 2–15. There was a production peak in 2011, with a rise to 78 resources published. After 2012 (although there was a drop then with respect to the previous year), the rising trend continued until 2014 and general production increased, with a mean of 30.3 publications per year and a minimum–maximum range of 24–42 resources.

A tendency in the type of resources published over time was also found. The resources that were developed most in the first period were implementation cost reports, “do not do” reminders and tools for assessing clinical and economic audits. This type of resources is normally produced and disseminated together with the clinical guidelines with which they are associated. Reports on implementation results or on the use of services began to appear in the second period, from 2010, with a significant increase in 2011. In the third period, quality standards were produced and published (mainly in 2011 and 2012), while care pathways began being distributed in 2014.

DiscussionAs a fundamental aspect, we can point out the important amount of resources, materials and documents designed and used by the NICE to help to implement CMHD treatment guidelines. There is also great variety within the study elements compiled. Some of them can be considered complementary or of a multilevel or multifaceted nature, such as care pathways, quality standards or assessment tools, among others. In some cases, this caused difficulties in our categorisation process due to overlap in objectives or scope. However, the ad-hoc categories designed made it possible to analyse each type of material more deeply and facilitate the classification process.

More specifically, we were able to synthesise the main findings reached in the following key elements.

First of all, we saw that most of the implementation resources are associated with clinical guidelines on mental disorders that are highly prevalent in Europe and around the world, and that involve elevated impact at the healthcare level.5,33 Consequently, it is evident that evaluating the impact and costs associated with each type of disease would be a key point in orienting decision-making about resource distribution. Such evaluation would also affect the development of strategies to improve access to effective treatments within the public healthcare system.

Secondly, we feel that the resources compiled would represent the highest level of NICE implementation strategy realisation, given that they are tools that are practical and easily accessed and applied. They are also designed specifically and aimed at different collectives. Consequently, professionals, managers and users play clearly defined and complementary roles within the guideline implementation process. Although it is true that the resources for professionals and managers are the most numerous, user-focused materials can also be found. Their goal is to help patients, relatives and caregivers to manage symptoms, through videos, books, information or links. Although we found few materials of this type in our study, the literature supports the actions that include the users as essential elements in the implementation process.9 That is why we consider that going deeper into this matter could be of interest for future studies.

In line with the analysis on resource characteristics, we found that the most frequent materials were the application tools. The objective of most of these tools is to evaluate the costs of implementing the guidelines, detect needs or ascertain how different centres or services are working. Joint application of these tools makes it possible to improve understanding of the characteristics of the local reality and estimate the impact that implementing a specific guideline or recommendation would mean in that particular context. Along these lines, various studies consider that actions aimed at increasing knowledge of a situation itself are potentially effective,11,13 because they promote implementing guidelines more flexibly, adjusted to the needs and resources of each context; in this way, the barriers to the applicability of those guidelines are reduced. Other authors emphasise that more actions of this type need to be developed, ones aimed at generating proactive attitudes by professionals and managers, for assessing costs and evaluating local implications of local implementation.9,10,19,20 This strategy is complemented with the publication of reports, articles and guidebooks that improve understanding of global reality and support implementation.

A third axis of analysis is related to the implementation strategies used by NICE. It should be pointed out that the resources are not put forward or designed in isolation; they are integrated in a series of key strategies aimed at reducing internal (mainly from the professionals), organisational and structural barriers that make implementing evidence-based treatments more difficult.11,12 We wish to emphasise 3 fundamental strategies. First of all, the strategy of interventions aimed at professionals, which focus on distributing materials and information to improve training and management of recommendations, and to promote making evidence-based decisions in daily practice. Along with, actions are carried out to adapt the format of guideline presentation, to make it clearer, simpler and more accessible. This type of actions reduces the barriers and encourage professionals to change their practices.11,20 In this way, in addition to the traditional CPG presentation in written format on paper or in PDF, online summaries and short references on “do not do” in typical care of certain disorders are also offered.

In second place, we find the structural and organisational strategies. We believe that these should be analysed together, because the actions and materials designed for them can be applied and act in a synergic, complementary manner in practice. Within these, we emphasise the role that pathways play, showing the steps and decisions to follow throughout the entire care process graphically and quickly. They are presented in digital format, in PDF and as smartphone apps. Although some authors demonstrate that this resource has some limitations and requires improvements, these flow diagrams are considered capable of facilitating the application of recommendations, increasing access to non-drug treatments and improving coordination among levels.34–36 Together, interventions focused on evaluating the needs and performance of the services are applied. This is complemented with assessment strategies and constant quality improvement, both of which define a series of standards and indicators to measure how much the professionals adjust their actions to guideline recommendations. The goal is to optimise monitoring of service practice and functioning.

Finally, we have seen that the chronological development in resource publication is not presented as a simple increase in the amount of material produced; there is a complex implementation process, with stages in resource design and strategy application, consistent with the recommendations of the most recent studies.13,14 We find that initially, together with the publication of each guideline, a series of basic tools are distributed. The main objectives of these tools are to provide information about tool content and facilitate estimating the costs that their implementation in a specific service or context would involve. In the next stage, the emphasis is placed on publishing reports about the results of implementing guidelines and services; there is also a commitment to defining and disseminating a series of quality standards that accompany each of the clinical guidelines. At present, the most recent trend is the design and publication of care pathways, attempting to encourage integrating CMHD treatment in the context of stepped care in various services.

ConclusionsApproaching CMHD is complex and involves coordination and interaction among professionals and levels. This makes clinical guideline application variable and has multiple barriers for effective implementation. Throughout this study, we have seen that simply preparing guidelines is insufficient for bringing about their transfer to daily practice. In addition, there has to be an active and directed incorporation of models, strategies and resources that increase the chances of real application of the guidelines available.

The synthesis implementation strategies and resources presented in this study are potentially applicable to other contexts and services. Likewise, they could orient professionals and managers in making informed decisions, and be used in planning and designing actions adjusted to specific realities. In this way, they could promote the applicability of clinical guidelines and improve access to effective treatments in public healthcare systems.

FundingThis study has been developed thanks in part to the funding of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Competitiveness (Project PSI2014-56368-R).

AuthorshipEliana María Moreno designed the study and its protocol; carried out the bibliographic search, the data extraction, the initial analysis and interpretation; and wrote the first version of the manuscript. Juan Antonio Moriana collaborated in the study design and the result analysis and interpretation, reviewed the article and gave final approval for its publication. Both authors participated in the critical review of the article and made important intellectual contributions.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Moreno EM, Moriana JA. Estrategias para la implementación de guías clínicas de trastornos comunes de salud mental. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2016;9:51–62.