The main purpose of this study was to examine the prevalence of symptoms of an emotional and behavioral nature, as well as prosocial type capabilities, measured using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, in non-clinical adolescents.

MethodThe final sample was composed of a total of 508 students, 208 male (40.9%). The age of participants ranged from 11 to 18 years (M=13.91 years; SD=1.71).

ResultsThe results show that a significant number of adolescents self-reported emotional and behavioral problems. The mean scores of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire subscales varied according the gender and age of the adolescents.

ConclusionsIn the present study, the prevalence of psychological difficulties among adolescents was similar to that reported in other national and international studies. In view of these results, there is a need to develop programs for the early detection of these types of problems in schools in children and adolescents ages.

El propósito principal del estudio fue examinar la prevalencia de los síntomas emocionales y comportamentales así como las capacidades de tipo prosocial, medidos con el Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, en adolescentes no clínicos.

MétodoLa muestra final estuvo compuesta por un total de 508 participantes españoles, 208 hombres (40,9%). La edad de los participantes osciló entre 11 y 18 años (M=13,91 años; DT=1,71).

ResultadosUn importante número de adolescentes informaron de sintomatología afectiva y comportamental. Las puntuaciones medias de las subescalas del Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire variaron de forma estadísticamente significativa en función del género y la edad de los adolescentes.

ConclusionesLa prevalencia de dificultades de tipo psicológico entre adolescentes fue similar a la informada en estudios previos, tanto en el panorama nacional como internacional. A la vista de los resultados, existe una necesidad de desarrollar programas de detección temprana de este tipo de síntomas emocionales y comportamentales en los centros escolares y/o asistenciales en población infanto-juvenil.

Mental health problems in children and adolescents seriously affect not only the individuals themselves but also the family, the school environment and the community.1 Over the last 2 decades interest in identifying children and adolescents at the risk of having some type of emotional and/or behavioral disorder has increased.2 In spite of the efforts expended on this early detection, several studies suggest that only a minority of the child and youth population with intervention needs in the area of mental health enter in direct contact with specialised services.3,4 The strategies for primary prevention (preventing the appearance of symptoms) and for secondary prevention (identifying and treating asymptomatic individuals that have developed risk factors or subclinical features, but whose clinical condition has not yet appeared) are still underdeveloped in the child and youth population.5

According to a national survey on mental health carried out in Spain,6 22.1% of Spanish children and adolescents from 4 to 15 years old present the risk of having a mental or behavioral disorder (e.g., behavior problems). Child and youth epidemiological studies also carried out in our territory yield similar prevalence rates for the different emotional and behavioral problems,7–10 which resembled those found in the general population.11,12 These results also coincide with those found in epidemiological studies in other countries. International prevalence rates for mental disorders in children and adolescents, classified according to the diagnostic criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) and/or the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (Clasificación internacional de enfermedades, 10 edición, CIE-10), are approximately 5% and 20% of the population,13–17 with the mean rate being on the order of 15%.18,19

As can be seen, a high percentage of children and adolescents present or will present a mental disorder at some time throughout their lives. This will cause a clear impact, not only on the person, academic, family and social spheres, but also at the healthcare and economic levels.14,15,20 In addition, many mental disorders seem to begin in childhood and/or adolescence. Approximately 50% start before the age of 15 years and, in many cases, this symptomatology remains stable until adulthood.13,21–23 What is more, it should be remembered that the presence of affective and behavioral symptoms at subclinical level increases the later risk of developing a serious mental disorder.24–27 Based on these prevalence data, and bearing in mind the economic and social costs that mental health problems generate in this segment of the population,14,15 it is undoubtedly highly important to perform reliable and valid detection and assessment of the emotional and behavioral symptoms in the child and youth population. Precise assessment lets us understand the prevalence rates of mental health better and makes it possible to improve the management of economic and/or healthcare resources.

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)28 (Cuestionario de Capacidades and Dificultades), in its self-report version, is a measurement tool used for screening of behavioral and emotional symptoms, as well as for the evaluation of prosocial capacities. The use of the SDQ makes it possible to obtain reliable, valid information on the expression of emotional and behavioral symptoms; at the same time, it is a brief, simple and easily-administered questionnaire for use in the child and youth population.29,30

Emotional and behavioral symptoms assessed using the SDQ seem to vary based on gender and age of the adolescents. Similar data are found in epidemiological studies with other measurement instruments.13,33 As for gender, females obtain higher mean scores than males in emotional symptoms and prosocial behavior; in contrast, males obtain higher mean scores than females in behavior problems, hyperactivity and relationship problems.34–44 With respect to age, results are not conclusive yet. Some studies found greater emotional and behavioral symptoms as age increased,35,36,38,42 while others showed an inverse tendency,40,45 or did not find any kind of link.46

Until now, in Spain few empirical studies have been carried out that give information on the prevalence of symptoms of emotional and behavioral type measured using the SDQ. Within this research context, the main objective of this study was to examine the prevalence rates of emotional and behavioral symptomatology, using the SDQ,28 in a sample of adolescents from the general Spanish population. Likewise, we analysed the expression of the affective and behavioral symptoms and of behavior and prosocial capacities based on gender and age. Studying the prevalence rates of emotional and behavioral symptoms provides us with better understanding of child and youth psychopathology and makes it possible to improve public health systems at the level of early detection and intervention, along with improving treatment and resource management. In agreement with prior studies, we subscribed to the hypothesis that the percentage of adolescents that would self-report emotional and behavioral symptoms would be high. Likewise, we hypothesised that the behavioral and affective symptoms would vary based on the gender and age of the participants.

MethodParticipantsParticipants were selected using convenience sampling. Due to the type of sampling, and to guarantee the sample was as representative as possible, 8 state and partially funded school centres of compulsory secondary education in the autonomous communities of the Principado de Asturias and La Rioja were chosen. All the centres and classrooms chosen participated in the study. The school centres belonged to different socioeconomic strata (preferably middle level) and geographic areas (rural and urban). The final convenience sample was formed 508 students, 208 males (40.9%). Participants’ ages varied between 11 and 18 years (M=13.91; SD=1.71). Final sample distribution of age was as follows: 11 years (n=31; 6.1%), 12 years (n=95; 18.7%), 13 years (n=93; 18.3%), 14 years (n=94; 18.5%), 15 years (n=106; 20.9%), 16 years (n=55; 10.8%), 17 years (n=20; 3%) and 18 years (n=14; 2.8%).

InstrumentsWe used the self-report version of the SDQ.28 This questionnaire is composed of 25 items grouped into 5 subscales or dimensions28: Emotional problems, behavior problems, hyperactivity, peer relationship problems and prosocial abilities. The first 4 subscales make up a Total Difficulties score. The SDQ uses a 3-option Likert response format (No, never–0; Sometimes–1; Yes, always–2). The items that comprise the SDQ are formulated both positively and negatively, to avoid response bias. In all, 15 affirmations reflect problems and 10 capacities, of which 5 belong to the prosocial subscale. In addition, 5 of the items had to be recodified. The score for each subscale ranges from 0 to 10 points and the Total Difficulties score, from 0 to 40. Higher scores indicate greater emotional and behavioral symptomatology, except for the prosocial subscale. In the self-report version of the SDQ, a Total Difficulties score of 0–15 is considered as normal, a score of 16–19 is on the border-line and a score of 20–40 is considered to be abnormal or pathological (http://www.sdqinfo.com). These score cut-off points showed 80% of adolescents with a normal score, 10% in the borderline band and 10% with pathological scores in the United Kingdom,31 although other studies32 showed up to 85% of adolescents with scores in the normality band. In our study we used the version adapted and translated to Spanish, which is available on Internet (http://www.sdqinfo.com).47

ProcedureThe measuring tool was administered in groups of 15–25 participants, who had been informed previously of the confidentiality of their answers and the voluntary nature of their participation. A classroom in each school centre that had been adapted for this was used during school hours. We obtained informed consent in the centres where the data were collected. The SDQ was administered under the supervision of the researchers. Participants did not receive any monetary or other incentive. To gather the information, informed consent of the centres was obtained. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Oviedo (Spain). This study falls within the framework of a wider study whose objective is to examine the mental health of adolescents.

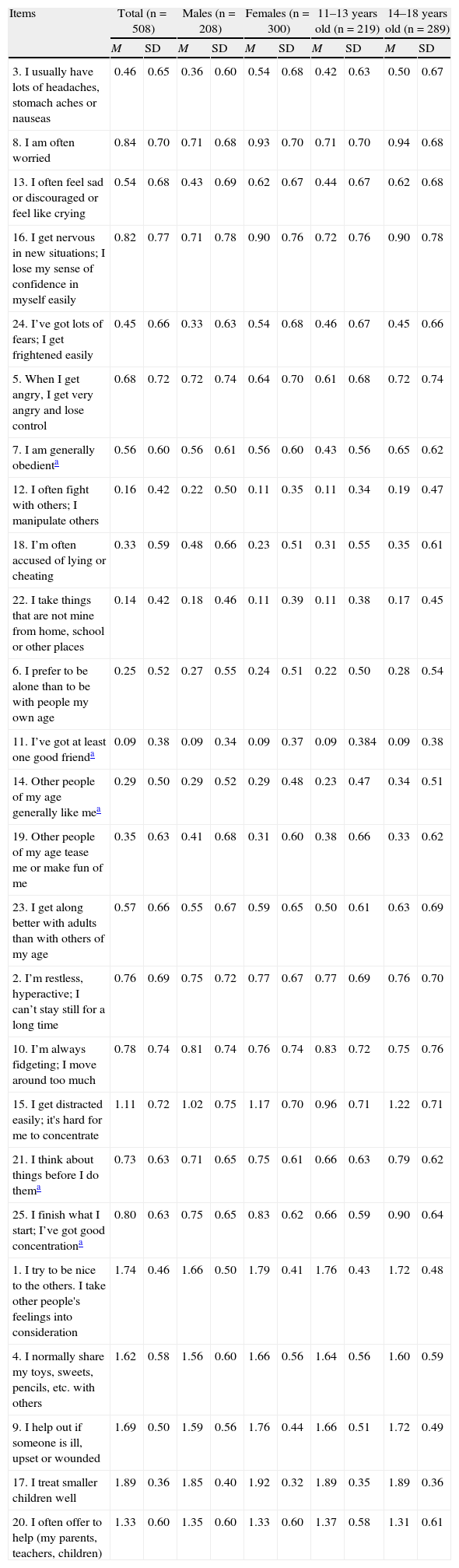

ResultsDescriptive statisticsTable 1 presents the mean scores and standard deviations of the answers to the SDQ items, with attention to both the total sample and gender, and to the 2 age groups (11–13 years and 14–18 years). The mean score for Total Difficulties for the entire sample was 10.73 (SD=5.46). Among the males, the mean score for difficulties was 10.38 (SD=5.64), with the scores varying from 1 to 26. Among the females, the mean score for difficulties was 10.98 (SD=5.32), ranging from 0 to 30. As for age, the mean score for Total Difficulties for the group of 11–13 years was 9.61 (SD=5.37), while it was 11.59 (SD=5.37) for the group of 14–18 years. The estimated cut-off points for Spanish adolescents showed that 85% obtained a score ≤16, 9% fell on the limit band between the scores 16 and 19, and 6% of the adolescents were located above the score of 20, with a maximum score of 30.

Descriptive Statistics for the Items on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ).

| Items | Total (n=508) | Males (n=208) | Females (n=300) | 11–13 years old (n=219) | 14–18 years old (n=289) | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| 3. I usually have lots of headaches, stomach aches or nauseas | 0.46 | 0.65 | 0.36 | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.68 | 0.42 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.67 |

| 8. I am often worried | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.94 | 0.68 |

| 13. I often feel sad or discouraged or feel like crying | 0.54 | 0.68 | 0.43 | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.44 | 0.67 | 0.62 | 0.68 |

| 16. I get nervous in new situations; I lose my sense of confidence in myself easily | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.78 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.76 | 0.90 | 0.78 |

| 24. I’ve got lots of fears; I get frightened easily | 0.45 | 0.66 | 0.33 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.66 |

| 5. When I get angry, I get very angry and lose control | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.74 |

| 7. I am generally obedienta | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.62 |

| 12. I often fight with others; I manipulate others | 0.16 | 0.42 | 0.22 | 0.50 | 0.11 | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.47 |

| 18. I’m often accused of lying or cheating | 0.33 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.66 | 0.23 | 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.55 | 0.35 | 0.61 |

| 22. I take things that are not mine from home, school or other places | 0.14 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.46 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.11 | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.45 |

| 6. I prefer to be alone than to be with people my own age | 0.25 | 0.52 | 0.27 | 0.55 | 0.24 | 0.51 | 0.22 | 0.50 | 0.28 | 0.54 |

| 11. I’ve got at least one good frienda | 0.09 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 0.384 | 0.09 | 0.38 |

| 14. Other people of my age generally like mea | 0.29 | 0.50 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.29 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.51 |

| 19. Other people of my age tease me or make fun of me | 0.35 | 0.63 | 0.41 | 0.68 | 0.31 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.66 | 0.33 | 0.62 |

| 23. I get along better with adults than with others of my age | 0.57 | 0.66 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.69 |

| 2. I’m restless, hyperactive; I can’t stay still for a long time | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.77 | 0.67 | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.70 |

| 10. I’m always fidgeting; I move around too much | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.76 |

| 15. I get distracted easily; it's hard for me to concentrate | 1.11 | 0.72 | 1.02 | 0.75 | 1.17 | 0.70 | 0.96 | 0.71 | 1.22 | 0.71 |

| 21. I think about things before I do thema | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.79 | 0.62 |

| 25. I finish what I start; I’ve got good concentrationa | 0.80 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.90 | 0.64 |

| 1. I try to be nice to the others. I take other people's feelings into consideration | 1.74 | 0.46 | 1.66 | 0.50 | 1.79 | 0.41 | 1.76 | 0.43 | 1.72 | 0.48 |

| 4. I normally share my toys, sweets, pencils, etc. with others | 1.62 | 0.58 | 1.56 | 0.60 | 1.66 | 0.56 | 1.64 | 0.56 | 1.60 | 0.59 |

| 9. I help out if someone is ill, upset or wounded | 1.69 | 0.50 | 1.59 | 0.56 | 1.76 | 0.44 | 1.66 | 0.51 | 1.72 | 0.49 |

| 17. I treat smaller children well | 1.89 | 0.36 | 1.85 | 0.40 | 1.92 | 0.32 | 1.89 | 0.35 | 1.89 | 0.36 |

| 20. I often offer to help (my parents, teachers, children) | 1.33 | 0.60 | 1.35 | 0.60 | 1.33 | 0.60 | 1.37 | 0.58 | 1.31 | 0.61 |

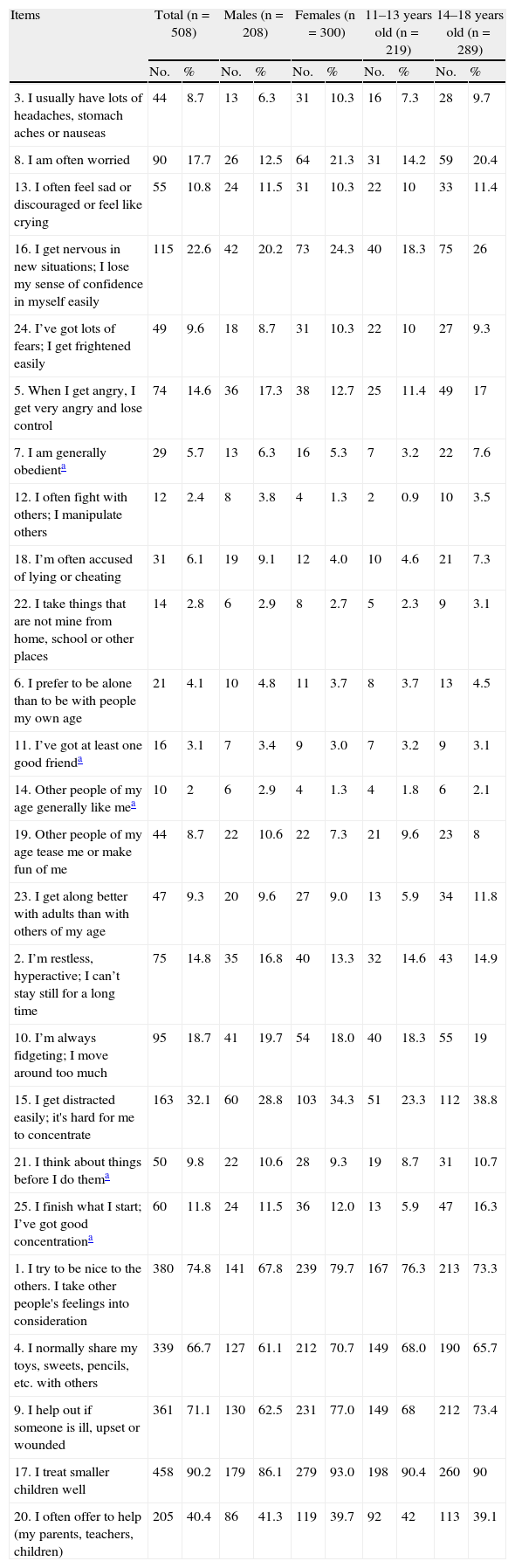

Table 2 shows the results obtained from analysing the items of the SDQ for males and females separately, and based on the 2 age groups. It includes the number and percentage of adolescents that responded affirmatively; that is, they scored “Yes, always” (2 points) in the response options of the SDQ. As for analysing the results, it should be pointed out that the items belonging to the prosocial subscale involve interpretation in a positive sense; that is, a score of 2 reflects the presence of prosocial conducts and not that of problematic. In contrast, the items formulated in a positive form that belong to the difficulty subscales have to be recoded. For example, in Item 7 “I’m generally obedient”, 5.7% of the sample chose the response option “No, never”; that is, 5.7% of the participants are generally not obedient.

Number and percentage of participants responding “Yes, always” in the response options on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ).

| Items | Total (n=508) | Males (n=208) | Females (n=300) | 11–13 years old (n=219) | 14–18 years old (n=289) | |||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 3. I usually have lots of headaches, stomach aches or nauseas | 44 | 8.7 | 13 | 6.3 | 31 | 10.3 | 16 | 7.3 | 28 | 9.7 |

| 8. I am often worried | 90 | 17.7 | 26 | 12.5 | 64 | 21.3 | 31 | 14.2 | 59 | 20.4 |

| 13. I often feel sad or discouraged or feel like crying | 55 | 10.8 | 24 | 11.5 | 31 | 10.3 | 22 | 10 | 33 | 11.4 |

| 16. I get nervous in new situations; I lose my sense of confidence in myself easily | 115 | 22.6 | 42 | 20.2 | 73 | 24.3 | 40 | 18.3 | 75 | 26 |

| 24. I’ve got lots of fears; I get frightened easily | 49 | 9.6 | 18 | 8.7 | 31 | 10.3 | 22 | 10 | 27 | 9.3 |

| 5. When I get angry, I get very angry and lose control | 74 | 14.6 | 36 | 17.3 | 38 | 12.7 | 25 | 11.4 | 49 | 17 |

| 7. I am generally obedienta | 29 | 5.7 | 13 | 6.3 | 16 | 5.3 | 7 | 3.2 | 22 | 7.6 |

| 12. I often fight with others; I manipulate others | 12 | 2.4 | 8 | 3.8 | 4 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.9 | 10 | 3.5 |

| 18. I’m often accused of lying or cheating | 31 | 6.1 | 19 | 9.1 | 12 | 4.0 | 10 | 4.6 | 21 | 7.3 |

| 22. I take things that are not mine from home, school or other places | 14 | 2.8 | 6 | 2.9 | 8 | 2.7 | 5 | 2.3 | 9 | 3.1 |

| 6. I prefer to be alone than to be with people my own age | 21 | 4.1 | 10 | 4.8 | 11 | 3.7 | 8 | 3.7 | 13 | 4.5 |

| 11. I’ve got at least one good frienda | 16 | 3.1 | 7 | 3.4 | 9 | 3.0 | 7 | 3.2 | 9 | 3.1 |

| 14. Other people of my age generally like mea | 10 | 2 | 6 | 2.9 | 4 | 1.3 | 4 | 1.8 | 6 | 2.1 |

| 19. Other people of my age tease me or make fun of me | 44 | 8.7 | 22 | 10.6 | 22 | 7.3 | 21 | 9.6 | 23 | 8 |

| 23. I get along better with adults than with others of my age | 47 | 9.3 | 20 | 9.6 | 27 | 9.0 | 13 | 5.9 | 34 | 11.8 |

| 2. I’m restless, hyperactive; I can’t stay still for a long time | 75 | 14.8 | 35 | 16.8 | 40 | 13.3 | 32 | 14.6 | 43 | 14.9 |

| 10. I’m always fidgeting; I move around too much | 95 | 18.7 | 41 | 19.7 | 54 | 18.0 | 40 | 18.3 | 55 | 19 |

| 15. I get distracted easily; it's hard for me to concentrate | 163 | 32.1 | 60 | 28.8 | 103 | 34.3 | 51 | 23.3 | 112 | 38.8 |

| 21. I think about things before I do thema | 50 | 9.8 | 22 | 10.6 | 28 | 9.3 | 19 | 8.7 | 31 | 10.7 |

| 25. I finish what I start; I’ve got good concentrationa | 60 | 11.8 | 24 | 11.5 | 36 | 12.0 | 13 | 5.9 | 47 | 16.3 |

| 1. I try to be nice to the others. I take other people's feelings into consideration | 380 | 74.8 | 141 | 67.8 | 239 | 79.7 | 167 | 76.3 | 213 | 73.3 |

| 4. I normally share my toys, sweets, pencils, etc. with others | 339 | 66.7 | 127 | 61.1 | 212 | 70.7 | 149 | 68.0 | 190 | 65.7 |

| 9. I help out if someone is ill, upset or wounded | 361 | 71.1 | 130 | 62.5 | 231 | 77.0 | 149 | 68 | 212 | 73.4 |

| 17. I treat smaller children well | 458 | 90.2 | 179 | 86.1 | 279 | 93.0 | 198 | 90.4 | 260 | 90 |

| 20. I often offer to help (my parents, teachers, children) | 205 | 40.4 | 86 | 41.3 | 119 | 39.7 | 92 | 42 | 113 | 39.1 |

An important number of adolescents reported emotional and/or behavior symptoms. Specifically, 22.6% of the adolescents indicated “I get nervous in new situations; I lose my sense of confidence in myself easily” (Item 16), while 14.6% stated that “When I get angry, I get very angry and lose control” (Item 5). Likewise, 11.8% of the sample said “I finish what I start; I’ve got good concentration” (Item 25) and 3.1% that “I’ve got at least one good friend” (Item 11). These replies should be interpreted, once the values have been recoded, as indicating that, generally speaking, 11.8% of the adolescents do not finish what they start and 3.1% do not have a good friend, respectively. The figures for the items that reflect difficulties ranged from “I get distracted easily; it's hard for me to concentrate” (Item 15) with 32.1% and “Other people of my age generally like me” (Item 14), with 2%. This should be interpreted, the same as in the previous cases, as 2% are not generally liked by the other people of their age.

Putting our attention on the prosocial subscale, higher scores reference greater prosocial capacity. The values on this subsale for the entire sample varied between the 90.2% that stated that “I treat smaller children well” (Item 17) and the 40.4% that declared “I often offer to help (my parents, teachers, children)” (Item 20).

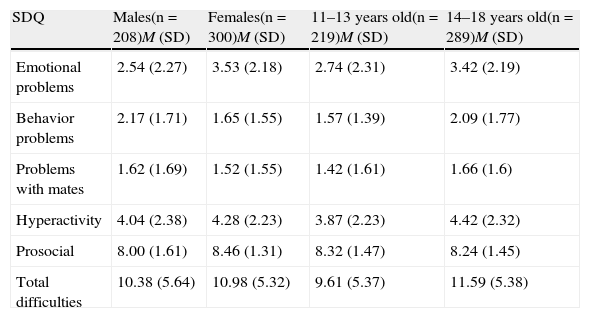

Comparisons of the mean scores on the subscales and the total difficulties score on the Strengths and Difficulties QuestionnaireNext, to examine the relationship between the different prosocial difficulties and capacities and the gender and age of the participants, we performed a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Gender and age (recoded into 2 groups: 11–13 years and 14–18 years) were selected as the fixed factors. The subscales and the Total Difficulties score on the SDQ were considered as dependent variables. To estimate the possible significant differences in all the dependent variables taken together, the value of Wilks lambda (λ) was used. To calculate the size of the effect, we used the statistic partial eta-squared (partial η2).

Wilks λ value revealed the presence of statistically significant differences based on the factors of gender (λ=0.890; F(5.500)=12.377; P≤.001; partial η2=0.110) and age (λ=0.961; F(35.2055)=4.010; P≤.001; partial η2=0.039). Specifically, the results of the univariate analysis showed statistically significant differences based on the gender factor in the subscales of emotional problems, behavior problems and prosocial relationships. Females had higher mean scores on the subscales of emotional problems (F(1.504)=19.38; P≤.001; partial η2=0.037) and prosocial (F(1.504)=5.45; P≤.001; partial η2=0.028) compared to the males. In contrast, the males had higher scores on the behavioral problems subscale (F(1.504)=16.84; P≤.001; partial η2=0.032) when compared with the females.

As for the variable age, the 14–18 year group obtained significantly higher scores on the subscales of emotional problems (F(1.504)=6.32; P=.012; partial η2=0.012), behavioral problems (F(1.504)=17.90; P≤.001; partial η2=0.034), hyperactivity (F(1.504)=7.11; P=.008; partial η2=0.014) and Total Difficulties score (F(1.504)=15.48; P≤.001; partial η2=0.030) compared with the younger group. Table 3 shows the mean scores and standard deviations of the 4 groups of participants based on gender and age on the different subscales and on the Total Difficulties score on the SDQ. No statistically significant difference was found in the interaction of gender with age in the subscales analysed.

Descriptive statistics in the subscale and total difficulty scores on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) by gender and age.

| SDQ | Males(n=208)M (SD) | Females(n=300)M (SD) | 11–13 years old(n=219)M (SD) | 14–18 years old(n=289)M (SD) |

| Emotional problems | 2.54 (2.27) | 3.53 (2.18) | 2.74 (2.31) | 3.42 (2.19) |

| Behavior problems | 2.17 (1.71) | 1.65 (1.55) | 1.57 (1.39) | 2.09 (1.77) |

| Problems with mates | 1.62 (1.69) | 1.52 (1.55) | 1.42 (1.61) | 1.66 (1.6) |

| Hyperactivity | 4.04 (2.38) | 4.28 (2.23) | 3.87 (2.23) | 4.42 (2.32) |

| Prosocial | 8.00 (1.61) | 8.46 (1.31) | 8.32 (1.47) | 8.24 (1.45) |

| Total difficulties | 10.38 (5.64) | 10.98 (5.32) | 9.61 (5.37) | 11.59 (5.38) |

The main objective of this study was to analyse the prevalence of emotional and behavioral symptomatology in Spanish adolescents, along with the capacities for relationships, in Spanish adolescents as measured using the SDQ in its self-report version.28 We also examined the relationship between gender and age, and the emotional and behavioral problems and the prosocial capacities. The results obtained emphasise that an important number of adolescents self-reported emotional and behavioral symptoms and that these were expressed in different forms based on gender and age. Given the results found, it could be interesting to develop programmes of early identification of this type of emotional and behavioral symptoms in school or healthcare centres (e.g., primary care). Likewise, using psychopathological screening measures, such as the SDQ, could improve the assessment and detection of emotional and behavioral symptomatology in this segment of the population. This would, in turn, make it possible to optimise the management of resources at multiple levels. In this sense, themes related to mental health are beginning to be one of the main strategies in the healthcare policies of governments.

If the total set of all the adolescents that participated in the study are considered, it can be seen that between 8.7% and 22.6% of the participants reported symptoms of an emotional type, while between 2.4% and 14.6% showed symptoms of a behavioral type. Likewise, between 2% and 9.3% of the adolescents declared having some type of problem in peer relationships, and between 9.8% and 32.1% reported symptoms related to hyperactivity. The results arising from this study agree with those obtained in previous research, at both the national and international level, which places the prevalence rates of problems of this type at between 5% and 20%,13–17,34 with the mean rate being on the order of 15%.33,48 All of these studies, beyond the diversity of instruments for gathering information, samples and analysis techniques, seem to show convergent results that indicate that emotional and behavioral symptoms are common in adolescence.

The percentage of adolescents that scored above the cut-off points established in the United Kingdom31 was slightly less in this study, both for the border-line band of scores sand for the abnormal or pathological scores. Establishing these cut-off points is highly useful insofar as it makes establishing objective comparisons of prevalence rates with other countries possible. Previous studies carried out in Spain with the SDQ34 did not permit establishing these cut-off points because a 5-option Likert format for the response was used (from complete disagreement to complete agreement), which made it hard to compare these results with other types of studies using the SDQ.

The self-reported emotional and behavioral symptoms of the adolescents varied based on gender and age. Looking at our results, females presented more emotional difficulties and higher scores in the prosocial subscale, while males reported more problems in conduct. These results coincide with the majority of the studies carried out to date,34–36,38,39,41–45,49 which indicate a greater presence of internalising issues among females and externalising among males, with higher prosocial scores for the females. For example, in the study of Svedin and Priebe39 with a sample of 1015 Swedish adolescents, statistically significant differences were found based on gender, with males scoring higher than women in behavioral problems and peer relationships, while females presented more emotional problems and greater prosocial behavior than males. At the national level, the results obtained by Fonseca-Pedrero et al.34 with a representative sample of Spanish adolescents were also similar to those found in this study, although more hyperactive symptoms and problems with peer relationships were found among the males in comparison with the females.

As for age, our results reveal that the older group (aged 14–18 years) presented higher mean scores in emotional, behavioral and hyperactive symptoms and in the Total Difficulties score comparing this group to the lower-aged group. Previous studies found similar results.34–36,42 For example, Giannakopoulos et al,35 using a sample of 1194 Greek adolescents, found that the group aged 15–17 years presented a higher score in the hyperactivity and behavioral problems subscales on the SDQ, in comparison with the group aged 11–14 years; nevertheless, other previous studies found that the youngest subjects obtained higher scores when they were compared with the older, in both the self-reported version of SDQ and in the version for parents and/or teachers,43,45,49,50 and even found an absence of relationship.46 The results found in the different investigations analysed did not show conclusive results with respect to the influence of age on the phenotypic expression of emotional and behavioral symptoms. Consequently, continued analysis of the role of age is of interest.

When interpreting the results obtained in our study, it is necessary to mention some possible limitations. First of all, the study focuses on the self-report version of SDQ for adolescents. It should be remembered that there are inherent limitations in self-reports, such as possible lack of understanding and interpretation of the items or response bias. It would have been interesting to obtain information from other informants, for example, the parents and/or teachers. Specifically, the multi-informant system could be of special relevance in detecting symptoms of a behavioral nature, as well as those related to prosocial behavior, given that they are the ones that can be affected to a greater degree by bias from the self-report format itself, such as social desirability. In the second place, the transversal nature of the study precluded establishing cause–effect inferences. In the third place, the participant sample was selected by convenience sampling, so caution should be used in generalising the results. Finally, no information was gathered on possible psychiatric morbidity, either for the participants or close relatives, which could affect the results found in the study.

Future studies of a longitudinal type would make it possible to determine the development of emotional and behavioral problems precisely, as well as the expression of capacities of a prosocial type. This would facilitate establishing possible risk factors and protective factors in the expression of the issues of psychological disorders in adulthood. Likewise, it would be interesting to include different mental health tests to enable evaluation of emotional and behavioral difficulties and capacities, with other self-reports51 and/or clinical variables. Equally, using the SDQ in other regions would make it possible to compare the prevalence rates in various areas and zones within the country, as well as the management of healthcare and research resources.52

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on human beings or on animals for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in the article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained informed consent from the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. This document is in the power of the corresponding author.

FundingThis research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICINN), by the institute Carlos III and Centre for Biomedical Research in Mental Health Network (CIBERSAM). Project references: PSI 2011-28638 and PSI 2011-23818.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ortuño-Sierra J, Fonseca-Pedrero E, Paíno M, Aritio-Solana R. Prevalencia de síntomas emocionales y comportamentales en adolescentes españoles. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2014;7:121–130.