The prescribing of anti-psychotic drugs has become a normal clinical practice.

MethodsThis article presents a longitudinal, multicentre 12-months-long study conducted on 266 children and adolescents who were prescribed a first or second generation antipsychotic drug for the first time, and the baseline results of the study. The follow-up protocol had its purpose to detect the possible appearance of metabolic, cardiological, and motor changes.

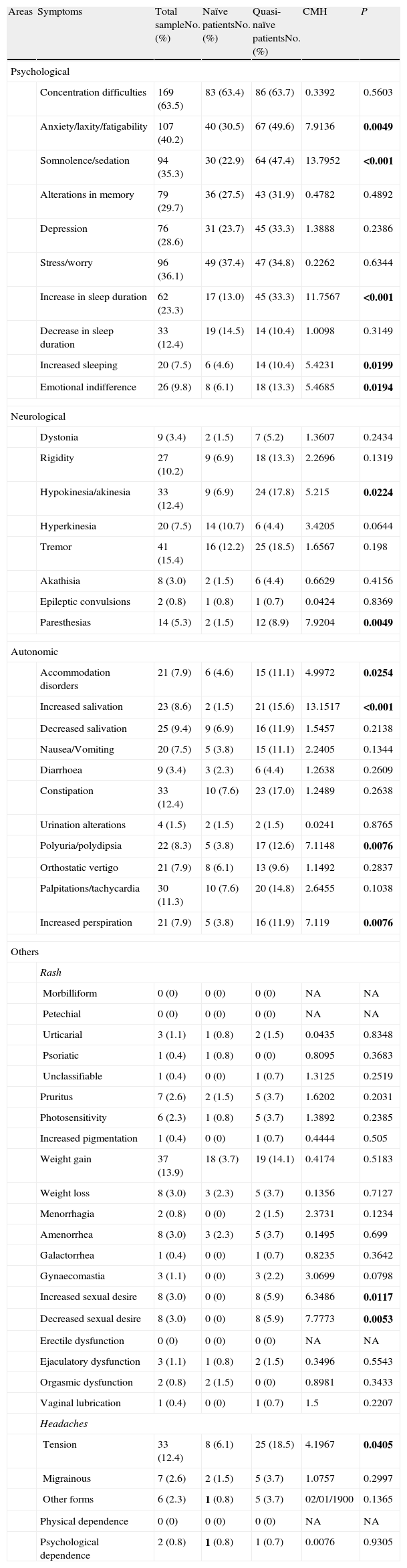

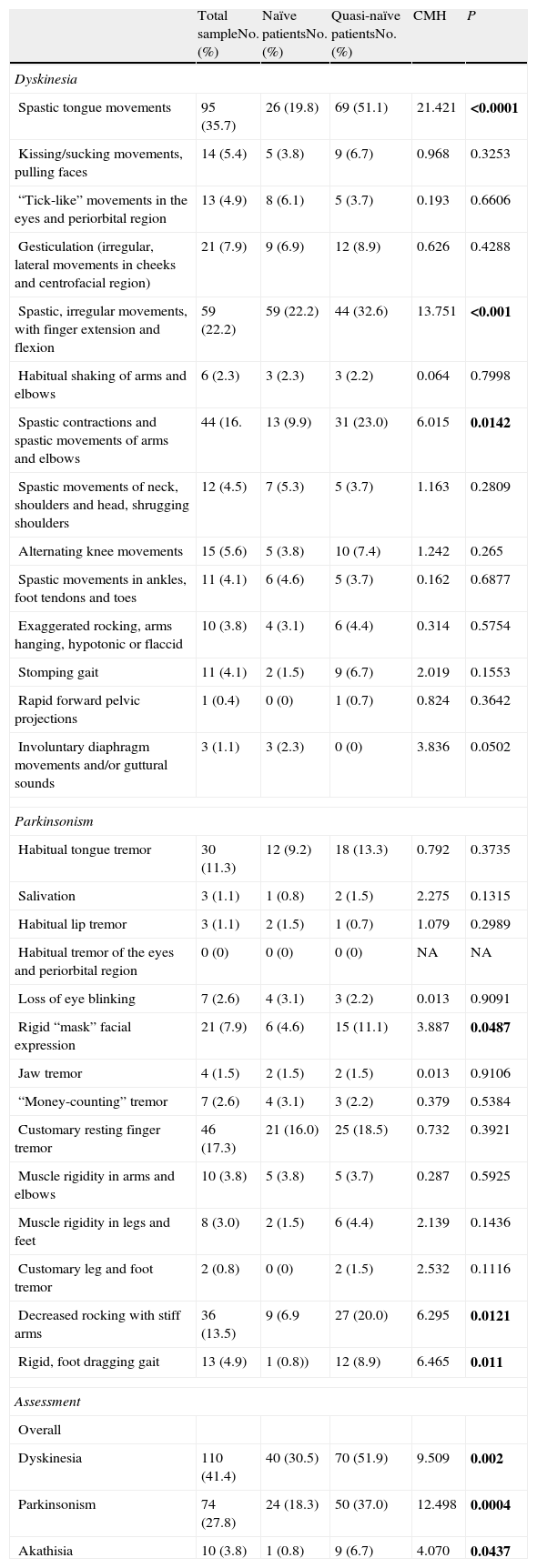

ResultsWhen the presence of side effects was evaluated using the UKU (clinical side-effects scale) statistically significant differences were found between naïve (patients who had never taken an anti-psychotic drug) and quasi-naïve patients (those who have taken anti-psychotic drugs for a period of less than 30 days), with a greater number of the latter showing symptoms of: anxiety/laxity/tiredness (P=0.0049), drowsiness/sedation (P<0.001), increase in dream duration (P<0.001), increase in dreams (P=0.0199), emotional indifference (P=0.0194), hypokinesia/akinesia (P=0.0224), paresthesias (P=0.0049), accommodation disorder (P=0.0254), increase in salivation (P<0.001), polyuria/polydipsia (P=0.0076), increase in sweating (P=0.0076), increase in sexual desire (P=0.0117), decrease in sexual desire (P=0.0053), tension headaches (P=0.0405). When the presence of extrapyramidal symptoms was assessed using the MPRC-IMS (Maryland Psychiatry Research Center-Involuntary Movement Scale), it was observed that the quasi-naïve patients had a statistically higher number of dyskinesia (P=0.002), Parkinsonism (P=0.0004) and akathisia (P=0.0437) symptoms compared to the naïve patients.

ConclusionsThese results show that, in the childhood–adolescent population, the presence of secondary effects begins to be observed from the first dose of the antipsychotic drug.

La prescripción de fármacos antipsicóticos en niños y adolescentes se ha convertido en una práctica habitual.

MétodosEste artículo presenta el diseño de un estudio multicéntrico longitudinal a 12 meses con 266 niños y adolescentes a los que se les prescribió por primera vez un antipsicótico de primera o segunda generación y los resultados basales del estudio. El protocolo de seguimiento tuvo como finalidad detectar la posible aparición de cambios metabólicos, cardiológicos y motores.

ResultadosCuando se valoró la presencia de efectos secundarios a través de la UKU (Udvalg für Kliniske Undersogelser) se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre pacientes naïve (pacientes incluidos que nunca habían tomado antipsicótico) y quasi-naïve (aquellos que habían tomado antipsicóticos durante un periodo inferior a 30 días), mostrando un mayor número de estos últimos síntomas de: ansiedad/laxitud/fatigabilidad (p=0,0049), somnolencia/sedación (p<0,001), aumento duración sueños (p<0,001), aumento de sueños (p=0,0199), indiferencia emocional (p=0,0194), hipocinesia/acinesia (p=0,0224), parestesias (p=0,0049), trastorno de acomodación (p=0,0254), aumento de la salivación (p<0,001), poliuria/polidipsia (p=0,0076), aumento de la sudoración (p=0,0076), aumento del deseo sexual (p=0,0117), disminución del deseo sexual (p=0,0053), cefaleas tensionales (p=0,0405). Cuando se valoró la presencia de síntomas extrapiramidales con la MPRC-IMS (Maryland Psychiatry Research Center-Involuntary Movements Scale) se observó que los pacientes quasi-naïve presentaron un número estadísticamente superior de síntomas de discinesia (p=0,002), parkinsonismo (p=0,0004) y acatisia (p=0,0437) con respecto a los naïve.

ConclusionesEstos resultados ponen de manifiesto que en población infanto-juvenil, la presencia de efectos secundarios se comienza a observar ya desde el inicio de la toma de fármacos antipsicóticos.

In the last few years, the prescription of antipsychotic drugs has increased, both for psychotic disorders as well as for other mental disorders in children and adolescents.1–5 Despite the limited indications for these treatments in this age group,6,7 this practice is becoming a habit in psychiatric clinical practice, especially in the case of the second generation [atypical] antipsychotics (SGA).8–11

Studies on the prevalence of use of antipsychotics in the paediatric population have shown a progressive decrease in the use of first generation antipsychotic (FGA) drugs,12 accompanied by a significant increase in SGA prescriptions.2,11 A UK study found a rise in SGA prescriptions in the child–adolescent population of almost 60 times (jumping from 0.01 users per 1000 patients in 1994 to 0.61 users per 1000 patients in 2005).12 Likewise, another USA study found an increase of 160% in the years from 1990 to 2000.7 This rise has been observed not only in prescriptions, but also in the period of exposure to these drugs (from 0.8 months in 1998–1999 to 1.6 months in 2001).13

The data to date have shown that the SGA as a group having fewer adverse neurological motor effects than the FGA in children and adolescents5,14; in contrast, most FGA are associated with an increase in the risk of metabolic complication (obesity, type II diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disorders).4,5,14–17

The current literature reflects a relevant aspect: the stability over time of the metabolic side effects of the various antipsychotic drugs. In a study with adolescents and adults, there was a weight increase, greater in the olanzapine group (olanzapine>risperidone>haloperidol) after 3 months’ treatment with antipsychotics (olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol).18 In contrast, when the weight gains were compared after 12 months of treatment, there were no significant differences among the 3 groups. In a study19 performed on adolescents with a first psychotic episode treated with olanzapine or quetiapine, the group treated with olanzapine had a greater weight gain after 6 months of follow-up than the group treated with quetiapine (olanzapine Δ 15.5kg; quetiapine Δ 5.5kg); the body mass index (BMI) showed similar results (olanzapine Δ 5.4 points; quetiapine Δ 1.8 points). Another study16 with children and adolescents treated with olanzapine, quetiapine or risperidone found a significant increase in weight in 50% of the sample at 6 months’ follow-up and significantly significant increases in the BMI z-score, in both the olanzapine and the risperidone groups. Similar data were obtained in another 12-month longitudinal study20 with a naïve child–adolescent population. The same effect on the BMI z-score in that study in the 3 treatment groups (olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone) at 12 months’ follow-up; this increase was significantly greater in the first 6 months of treatment.

When dealing with metabolic side effects in the paediatric population, it is important to remember that psychotic disorders represent a greater risk per se associated to the appearance of metabolic complications, as backed by studies on adults.21 In a recent study22 with children and adolescents, there was a greater incidence of overweight associated with obesity complications (hypertension, dyslipidemia and hyperglycaemia) linked to SGA treatment in naïve adolescents diagnosed with bipolar disorder than in subjects with any other diagnosis. Nevertheless, the weight gain after 3 months of SGA treatment was 5.5kg in this same study, with no differences by diagnosis. This indicates that the SGA affect the metabolic parameters of minors negatively, whatever pathology they present.

Bearing in mind that the paediatric population is more vulnerable than the adult one to side effects from antipsychotic drugs (and that it is also more sensitive to the negative impact these effects have on body image or self-esteem), the need to increase research that involves these aspects is evident.

Despite the studies carried out, there are still important data to ascertain. The majority of the research is performed with patients who have taken antipsychotics, during more or less long periods before the patients are included in the studies. This fact introduces factors of confusion in data interpretation. In addition, the studies published to date include short follow-up periods16,19,23; this constitutes a limitation in determining if the side effects become stable, improve or disappear—or if, in contrast, they continue increasing throughout the entire exposure period.

Based on the data indicated, it seems necessary to expand and explore the causal relationship between the appearance of adverse side effects and the administration of antipsychotic drugs in the paediatric population.

Our study aimed to provide the protocol for a study whose goal was to measure the possible appearance of metabolic, heart and motor changes throughout the 12 months of follow-up, in children and adolescents who had received first and second generation antipsychotics for the first time. The baseline study data were also included. Our study hypothesis was that the patients who were already taking antipsychotic treatment in the baseline visit would present a greater number of side effects characteristic of the antipsychotic medication than those that, when included in the study, were patients who had not taken antipsychotics previously.

Materials and methodsSampleThis was a naturalistic, observational, longitudinal multicentre study in which 4 Spanish hospitals participated: Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (HGUGM) and Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús in Madrid, and Hospital Clínic and Hospital Sant Joan de Déu in Barcelona. The subjects were patients treated in out-patient consultations and in-hospital patients. Recruitment was carried out between May 2005 and February 2009.

The criteria for inclusion were: (1) children and adolescents between 4 and 17 years of age; (2) any psychiatric diagnosis based on the diagnostic criteria of the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)24; (3) medical prescription of antipsychotic medication, both first and second generation drugs; and (4) a period of antipsychotic drug taking less than 30 days at the moment of including the patient in the study.

The patients included in the study who had never taken antipsychotics were classified as naïve, while patients who had taken antipsychotics for less than 30 days when they were included in the study were classified as quasi-naïve.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the Clinical Ethics and Research Committee at each of the hospitals that collaborated in recruiting. The parents/legal guardians of the participants gave written informed consent and the minors agreed, guaranteeing data confidentiality. We offered the participants and/or their legal guardians the possibility of raising any questions deemed necessary, as well as the liberty to abandon the study whenever they wished.

Study follow-upThe study follow-up period was established as 1 year, with a total of 5 visits (baseline, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months). Each of the patients was given appointments through telephone calls. The appointment for the corresponding visit could not exceed the window established for the study (a third of the inter-visit period). Specifically, the windows for the 1, 3, 6 and 12-month visits were set as: ±10, ±20, ±30 and ±60 days, respectively.

In the baseline visit, we used a structured interview, with the patients and their parents or legal representatives. The data collected were demographic data, the patient's personal medical history, family medical-psychiatric history and use of toxic substances, as well as the past history of dystonias and extrapyramidal symptoms associated with any medications. All this information, except for the family medical-psychiatric antecedents, was collected in the rest of the visits as well to control for possible changes. The diagnoses were performed by psychiatrists trained for the child-juvenile population, based on the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria.24 Personal medical information collected was as follows: recurrent streptococcal pharyngitis, rheumatic fever, traumatic brain injury (TBI) with loss of consciousness, blood transfusion, encephalitis/meningitis, convulsions/epilepsy, heart diseases, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, overweight/obesity, allergies/asthma, arthritis, foetal exposure to drugs/alcohol, current psychosis, past psychosis, prior electroconvulsive therapy, lack of medical antecedents: always healthy, computed axial tomography (CAT)/magnetic resonance (MR) (with findings) and other illnesses (specifying which).

Family medical history data collected was recurrent streptococcal pharyngitis, rheumatic fever, Huntington's disease, Parkinson's disease, Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, overweight/obesity, heart diseases, affective disorders, psychotic disorders and other family illnesses (specifying which). In all these cases, the relative affected and whether or not the pathology was present were recorded.

When the study ended, a finalisation sheet, in which the date on which the patient finished participating in the study was recorded, was filled out. If the interruption was early, we indicated the reason (lost to follow-up, lost to follow-up but continued with medication, symptom remission, patient's lack of collaboration, persistent poor compliance, intolerance, lack of clinical response/intolerance, admission to a psychiatric hospital, death (specifying the cause) and others (specifying the cause)).

Biological measurementsHeight, weight, abdominal perimeter, blood sample (including haemogram and biochemical and hormonal parameters), blood pressure and electrocardiogram (ECG) for each patient were collected by the nursing team. This protocol was applied in all the study follow-up visits, apart from the visit on the month in which all the tests except for the ECG and blood sample were performed.

The biochemical parameters obtained were fasting glucose (prior food 9h before the extraction), triglycerides, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and homocisteine. Blood glucose, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and triglycerides were determined by enzymatic procedures using the Boehringer Mannheim/Hitachi 714 automated chemistry analyser (Boehringer Mannheim Diagnostics, Inc., Indianapolis, Ind.): (1) glucose test (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany); (2) cholesterol test (Boehringer Mannheim Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Ind.). Adams HA-8186 (Menarini, Zaventem, Belgium) high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to analyse HbA1c. In addition, the Hospital Clínic obtained the homocisteine values through fluorescence immunoassay (Abbot: AXSYM). The laboratory at each of the hospitals classified the data obtained taking into consideration the normality criteria (maximum and minimum) established for each of the parameters. The hormonal parameters measured were thyrotropin or thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine (FT4), adiponectin, leptin and ghrelin. Both TSH and FT4 were measured using radioimmunoassay (Diagnostic Product Corporation, Los Angeles, CA). Adiponectin and leptin values were determined only at the HGUGM in Madrid and the Hospital Clínic in Barcelona. In the HGUGM, the adiponectin figures were obtained in duplicate using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (BioVendor, ref: RD195023100) and those of leptin using ELISA (BioVendor, ref: RD191001100). In the Hospital Clínic in Barcelona, the leptin and adiponectin were obtained by radioimmunoassay (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO). The Hospital Clínic also obtained by ghrelin measurements by radioimmunoassay (Ghrelin-Total RIA Kit; Linco Research).

Weight and height were always measured with the same sliding-weight scale at each hospital. The scales utilised by the HGUGM, Clínic, HNJ and HSJD hospitals were the Asimed S.A., SosPanduri, Soehnle, Vogel & Halke Hamburg Model 701 and SECA 220, respectively. Weight was recorded in kilograms (kg) and height in metres. From these data, the BMI was calculated, being understood as: weight in kg/height in metres squared [kg/m2]. Considering that the age range for study inclusion was very wide (4–17 years) and that the children and adolescents were still growing, we also calculated the BMI z-score del BMI, in agreement with standard Spanish tables.25

For the ECG, the patient was lying down face up, using the same electrocardiograph at each hospital. The electrocardiographs used at the HGUGM, Clínic, HNJ and HSJD hospitals were: Delta 1Plus Digital Electrocardiogram, Siemens Scard 440, Delta 1Plus Digital Electrocardiogram and Bio-Tek (Lionheart-1), respectively. The parameters obtained with the ECG were the ventricular rhythm (beats per minute, bpm), PR (ms), QRS (ms), and QTc (ms).

The abdominal perimeter was measured at all the centres based on the protocol that the Spanish Society for Obesity Study (SEEDO) used. The procedure was performed with a flexible, metrically graduated measuring tape, with the subject in a standing position, unclothed and relaxed. The upper border of the iliac crest was located and the measuring tape was put around the waist above this point, parallel to the floor, making sure that the tape was snug but without compressing the skin. The reading was taken at the end of a normal exhalation. The abdominal perimeter percentiles of all the patients were found, based on the Spanish tables for children and adolescents.26

Blood pressure was taken with the patient lying down, using the same sphygmomanometer at each hospital; the devices used at the HGUGM, Clínic, HNJ and HSJD hospitals were: OMRON M 6 (HEM-700-1E) digital blood pressure monitor; OMRON M 6 (HEM-700-1E), Vital Signs Monitor 300 series (Welch Allyn) P/No. 810-1707-00 and HARTMANN TENSOVAL monitor, respectively. Blood pressure was assessed for each patient using the percentiles proposed by the International Task Force for BP.27

TreatmentIn each of the visits, we recorded in detail the antipsychotic drug prescribed for the patient, noting both changes to the antipsychotic and changes in dose. Likewise, all the concomitant drugs received by patient (antidepressants, stimulants, benzodiazepines, mood stabilisers and anticholinergics). In each visit, the dose of the antipsychotics was converted to chlorpromazine equivalents.28 For all of the patients, we recorded the daily intake dose of antipsychotics in each visit; later, the dose accumulated during the period from one visit to the other (dose×days of exposure) was calculated.

In the Madrid HGUGM and in the Barcelona Hospital Clínic, compliance to antipsychotic treatment was determined by measuring the plasma levels of the antipsychotic using HPLC (Alliance 2695). The rest of the centres based this determination on the psychiatrists’ criteria, because this technique was unavailable there. Study continuation criteria were that the patients had appropriate adherence to treatment and were taking for 12 months.

Use of toxic substancesRecording the use of toxic substances was carried out through an interview designed for the study, in which we asked the patients about their use of toxic substances with respect to tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, opiates, amphetamines and derivatives, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), inhalants and other substances (specifying which). We always recorded if there had been use or not; if there had been, we also noted the patient's use pattern (daily, at the weekend, occasionally). In the case of tobacco use, the number of cigarettes a day was also noted.

Clinical scalesIn each of the visits, the patients’ pubertal development was assessed. Likewise, we assessed the presence of side effects and involuntary movements provoked by the antipsychotic drugs.

Assessment of pubertal developmentTo assess pubertal development, the tables designed by Tanner29,30 were used. These divide breast and public and genital hair development into 5 levels; they make an objective assessment of pubertal progression possible and are used universally. The patients themselves were the ones who indicated the level in which they were, except in the case of the smaller children, in which the parents or guardians/legal representatives that accompanied them provided this information.

Assessment of side effects from the antipsychotic drugsTo assess the presence of side effects, we used the UKU (Udvalg für Kliniske Undersogelser) scale.31 This is an over-all measurement of the adverse psychological and physical effects that use of psychotropic drugs produces; it is constituted by 48 items grouped as follows: adverse psychological, neurological and autonomic effects and other symptoms (dermatological, photosensitivity, weight gain/loss, hormonal, sexual, headaches physical/psychological dependence on the drug). The items are scored from 0 to 3 points to determine the severity of the symptom: 0: indicates lack or doubtful presence of the symptom; 1: slight; 2: moderate; and 3: severe; 9: not assessed. The possible causal relationship of the drug with the symptoms was assessed by from 0 to 2 points to these items (0: indicates improbable; 1: possible; and 2: probable).

The UKU scale was administered using a semi-structured interview given by trained psychologists and psychiatrists.

Assessment of involuntary movementsTo assess the presence of involuntary movements, we used the MPRC-IMS.32 This consists of 28 items structured topographically into the following corporal areas: tongue, perioral region, eyes and periorbital region, face and jaw, fingers and wrists, arms and elbows, neck, shoulders and head, thighs and knees, lower legs and feet, arm movement and tension, gait, waist and respiration.

These items measured the presence of 2 extrapyramidal symptoms (dyskinesia and parkinsonism) linked with the antipsychotic drug use. Each item was scored from 0 to 7 points (0–1: none; 2–3: slight; 4–5: moderate; 6–7: severe).

The overall assessments of dyskinesia and parkinsonism were obtained by adding up the scores of the 14 items that constituted each of the subscales. The MPRC-IMS makes an overall assessment of akathisia possible through subjective observation by the psychiatrist/psychologist throughout the examination.

To administer the MPRC-IMS, one of the psychiatrists was trained by the authors of the scale, obtaining interclass correlation coefficients (ICC) of 0.8–0.9 in the various items constituting the scale. Afterwards, the rest of the psychologists and psychiatrists that participated in the assessment passed through the same training, requiring a minimum ICC of 0.8 for each item for them to be able to administer the scale.

Statistical analysisDescriptive or frequency analyses were performed depending on whether the variables were continuous or discrete, respectively. The presence of statistically significant differences between naïve and quasi-naïve groups at baseline level in the variables of age, sex, race and diagnosis was analysed; to do so, Student's t-test was used for the age variable and χ2 for the rest (sex, race and diagnosis). We compared the presence of side effects among the naïve and quasi-naïve groups, controlling by diagnosis, using a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test. For these analyses, we used the statistical package SPSS 18.0 for Windows. The statistical tests were carried out as 2-tailed tests and statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

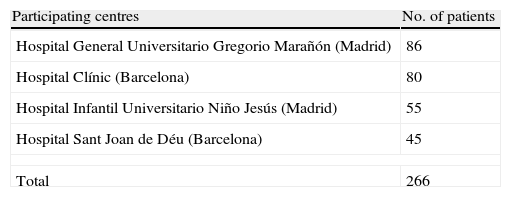

ResultsThe number of patients included in the study was 266 children and adolescents (Table 1). The descriptive sample analysis results are presented in Table 2. From the total of the sample analysed, 72.9% (n=194) were recruited during hospital admission. The rest came from external psychiatric consultations.

Baseline sample descriptors (n=266).

| Sex | |

| Males no. (%) | 148 (55.6) |

| Age | |

| Mean±SD | 14.4±2.91 |

| Race | |

| Caucasian no. (%) | 237 (89.1) |

| Diagnosis (DSM-IV criteria) no. (%) | |

| Bipolar disorder | 39 (14.7) |

| Unspecified psychosis | 38 (14.3) |

| Behaviour disorder | 38 (14.3) |

| Eating disorder | 30 (11.3) |

| Brief psychosis/Schizo-phreniform disorder | 25 (9.4) |

| Schizophrenia/Schizo-affective disorder | 17 (6.4) |

| Transient tic disorder | 13 (4.9) |

| Depression with psychotic symptoms | 13 (4.9) |

| Affective-depressive disorder without psychotic symptoms | 13 (4.9) |

| Attention hyperactivity deficit disorder | 9 (3.3) |

| Generalised development disorder | 9 (3.4) |

| Adaptive disorder | 9 (3.3) |

| Substance-related disorder | 6 (2.3) |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 4 (1.5) |

| Yes psychosis no. (%) | 150 (43.6) |

| Naïve patients no. (%) | 131 (49.2) |

| Period of previous antipsychotic use in quasi-naïve patients (days) | 5.32±7.56 |

| Mean daily dose±SD, mg/d (chlorpromazine equivalent) | 105.39±170.13 |

| Concomitant treatment | |

| Antidepressants no. (%) | 51 (19.2) |

| Benzodiazepines no. (%) | 76 (28.6) |

| Mood stabilisers (lithium/antiepileptic) no. (%) | 36 (13.5) |

| Stimulants no. (%) | 8 (3) |

| Use of toxic substances | |

| Tobacco no. (%) | 93 (35) |

| Alcohol no. (%) | 79 (29.7) |

| Cannabis no. (%) | 81 (30.68) |

| Amphetamines | 6 (2.3) |

| LSD | 2 (0.8) |

| Inhalants | 1 (0.4) |

LSD: lysergic diethylamide acid; naïve: patients who had not taken any antipsychotic drugs before being included in the study; quasi-naïve: patients who had taken antipsychotics for a period of less than 30 days before being included in the study; SD: standard deviation.

The results of analysing the personal medical histories recorded in the baseline visit of all of the patients were as follows: 43.6% with no medical antecedents, always healthy; 38% current psychosis; 24.1% allergies/asthma; 19.5% having received a CAT/MR at some time; 11.3% recurrent streptococcal pharyngitis; 8.3% TBI with loss of consciousness; 7.9% overweight/obesity; 7.1% past psychosis; 4.5% convulsions/epilepsy; 3% encephalitis/meningitis; 2.6% rheumatic fever; 2.6% heart diseases; 1.1% blood transfusion; 0.8% dyslipidemia; 0.8% foetal exposure to drugs/alcohol; 0.4% diabetes mellitus; 0.4% arthritis.

The family medical antecedents recorded at the baseline visits of all the patients (expressed in percentages) include at least 1 relative with the following pathologies: 42.49% affective disorders; 24.43% heart diseases; 23.68% diabetes; 22.18% overweight/obesity; 15.41% psychotic disorders; 12.78% recurrent streptococcal pharyngitis; 4.14% Parkinson's; 3.53% dyslipidemia; 3.38% rheumatic fever; 1.5% Tourette syndrome; and 0.36% Huntington's disease.

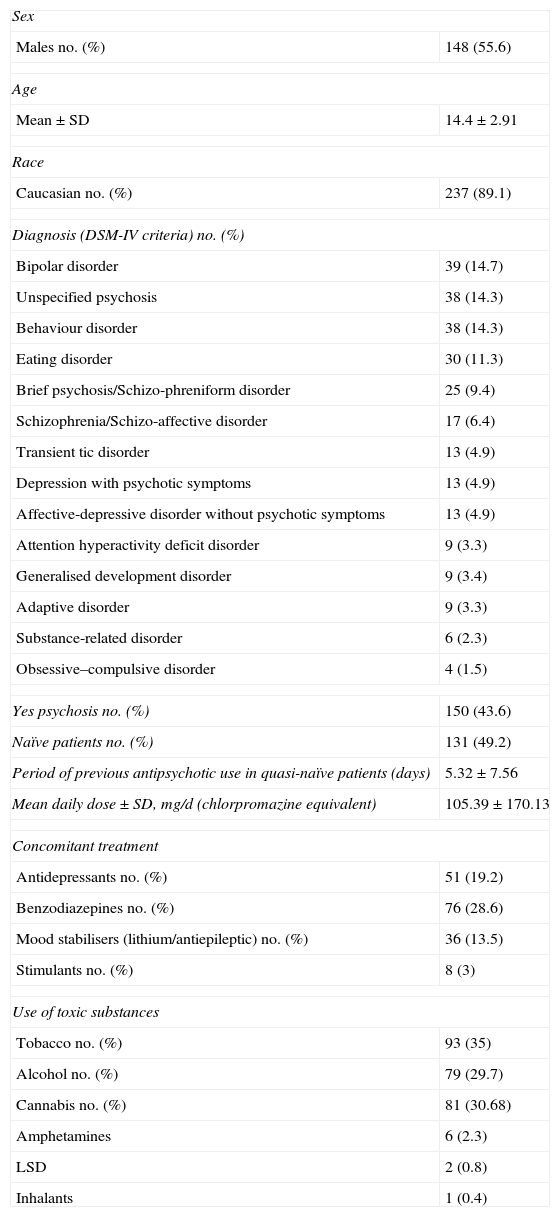

Biological measurementsThe mean and standard deviation (SD) value of the baseline sample BMI was 20.22±3.59kg/m2, and that of the abdominal perimeter was 74.61±10.71cm. In the case of blood pressure, the mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) at baseline level was 113.43±16.31mmHg, while the diastolic (DBP) was 65.19±12.00mmHg.

Table 3 presents the means and SD of the biochemical and haematological data from the blood extractions.

Baseline biochemical and haematological results.

| Mean±SD | Normal range | |

| Biochemical analyses | ||

| Glucose | 82.98±10.99 | 60–100mg/dL |

| Total cholesterol | 156.74±36.29 | <200mg/dL |

| HDL | 52.98±13.18 | 40–60mg/dL |

| LDL | 88.38±25.60 | <130mg/dL |

| Triglycerides | 70.22±39.75 | 50–150mg/dL |

| HbA1c | 4.72±0.57 | 4.0–6.0% |

| Haematological | ||

| Red blood cells | 4.79±0.46 | 4.60–5.70E6/μL |

| Haemoglobin | 14.06±1.40 | 13.0–17.5g/dL |

| Haematocrit | 41.33±3.96 | % |

| Leucocytes | 6.96±1.760 | E3/μL |

| Platelets | 263.03±65.12 | 140–400E3/μL |

| Hormones | ||

| TSH | 2.18±1.95 | 0.5–4.5U/ml |

| FT4 | 1.16±0.35 | 0.6–1.4ng/dL |

FT4: free thyroxine; HbA1c: glycated haemoglobin; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; SD: standard deviation; TSH: thyroid stimulating hormone.

Baseline leptin was collected by the HGUGM and Hospital Clínic in 122 patients, whose mean and SD was 9.91±12.92ng/mL; for adiponectin in 101 patients at these hospitals, the mean and SD was 11.43±4.64μg/mL. The baseline ghrelin and homocisteine were collected by the Hospital Clínic in 35 and 61 patients, respectively. The means and SD obtained for both parameters were 1095.94±408.15pg/mL in the case of ghrelin and 9.7±5.68μmol/l for homocisteine. Six visits by 6 patients, in which the absence of plasma antipsychotic levels was shown, were eliminated.

TreatmentAt the commencement of the study, 49.2% (n=131) were antipsychotic-naïve patients. The rest of the patients (50.8%), called quasi-naïve, received treatment with first generation (haloperidol=3, pimozide=1 and chlorpromazine=3) or second generation antipsychotics (risperidone=79, olanzapine=29, quetiapine=19 and aripiprazole=1). We measured the plasma levels of antipsychotics in 87 children and adolescents (32.7%) to check whether they had good adherence to the antipsychotic treatment prescribed, which all the patients analysed did. In the group of quasi-naïve patients, the mean number of days of exposure to antipsychotics before study inclusion was less than 6 days (Table 2). With a mean dose of chlorpromazine equivalents of the second antipsychotic prescribed of 361.59±265.87mg; 2.3% of the patients received combined treatment using 2 antipsychotics.

At baseline level, there were no statistically significant differences found between the naïve and quasi-naïve groups in the variables of age (t: 1.342; P=0.181), sex (χ2: 0.048; P=0.827) and race (χ2: 5.157; P=0.524). However, there was such a difference in diagnosis (χ2: 24.845; P=0.036), with there being a greater number of patients with a psychosis diagnosis in the quasi-naïve group. No significant differences were detected between both groups in weight, BMI and the SBP or DBP. In the analytical parameters, the only differences found were in prolactin (naïve group, 19.8, SD 13.1, vs quasi-naïve group, 37.7, SD 23.8; t=6.8, P<0.001).

The psychotropic drugs administered as concomitant treatment were antidepressants, mood stabilisers (lithium and antiepileptics), benzodiazepines and stimulants (Table 2).

Use of toxic substancesAs for the use of toxic substances, 35% (n=93) used tobacco at the moment of the baseline visit; the mean was 4.46 cigarettes/day and the most frequent use pattern was that of the weekend (n=44; 16.5%). The mean period of use before the baseline visit was 6.48±12.6 months.

The use of the rest of toxic substances recorded was as follows: cannabis, 30.68%, with the most frequent use pattern being daily use (16.66%); cocaine, 6.8%, with occasional being the most frequent use pattern (4.1%); amphetamines, 2.3%; LSD, 0.8%; and inhalants, 0.4%. The last 3 toxic substances (amphetamines, LSD and inhalants) were used with an occasional pattern. No patient indicated use of opiates.

Clinical scalesAssessment of the side effects from the antipsychotic drugsTable 4 presents the baseline results in the UKU scale for all the patients who obtained a score of at least slight in the symptoms assessed. For greater detail, analyses were performed on both the complete sample and differentiating between naïve and quasi-naïve patients controlled by baseline diagnosis.

Baseline scores for the UKU (Udvalg für Kliniske Undersogelser) scale.

| Areas | Symptoms | Total sampleNo. (%) | Naïve patientsNo. (%) | Quasi-naïve patientsNo. (%) | CMH | P |

| Psychological | ||||||

| Concentration difficulties | 169 (63.5) | 83 (63.4) | 86 (63.7) | 0.3392 | 0.5603 | |

| Anxiety/laxity/fatigability | 107 (40.2) | 40 (30.5) | 67 (49.6) | 7.9136 | 0.0049 | |

| Somnolence/sedation | 94 (35.3) | 30 (22.9) | 64 (47.4) | 13.7952 | <0.001 | |

| Alterations in memory | 79 (29.7) | 36 (27.5) | 43 (31.9) | 0.4782 | 0.4892 | |

| Depression | 76 (28.6) | 31 (23.7) | 45 (33.3) | 1.3888 | 0.2386 | |

| Stress/worry | 96 (36.1) | 49 (37.4) | 47 (34.8) | 0.2262 | 0.6344 | |

| Increase in sleep duration | 62 (23.3) | 17 (13.0) | 45 (33.3) | 11.7567 | <0.001 | |

| Decrease in sleep duration | 33 (12.4) | 19 (14.5) | 14 (10.4) | 1.0098 | 0.3149 | |

| Increased sleeping | 20 (7.5) | 6 (4.6) | 14 (10.4) | 5.4231 | 0.0199 | |

| Emotional indifference | 26 (9.8) | 8 (6.1) | 18 (13.3) | 5.4685 | 0.0194 | |

| Neurological | ||||||

| Dystonia | 9 (3.4) | 2 (1.5) | 7 (5.2) | 1.3607 | 0.2434 | |

| Rigidity | 27 (10.2) | 9 (6.9) | 18 (13.3) | 2.2696 | 0.1319 | |

| Hypokinesia/akinesia | 33 (12.4) | 9 (6.9) | 24 (17.8) | 5.215 | 0.0224 | |

| Hyperkinesia | 20 (7.5) | 14 (10.7) | 6 (4.4) | 3.4205 | 0.0644 | |

| Tremor | 41 (15.4) | 16 (12.2) | 25 (18.5) | 1.6567 | 0.198 | |

| Akathisia | 8 (3.0) | 2 (1.5) | 6 (4.4) | 0.6629 | 0.4156 | |

| Epileptic convulsions | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.7) | 0.0424 | 0.8369 | |

| Paresthesias | 14 (5.3) | 2 (1.5) | 12 (8.9) | 7.9204 | 0.0049 | |

| Autonomic | ||||||

| Accommodation disorders | 21 (7.9) | 6 (4.6) | 15 (11.1) | 4.9972 | 0.0254 | |

| Increased salivation | 23 (8.6) | 2 (1.5) | 21 (15.6) | 13.1517 | <0.001 | |

| Decreased salivation | 25 (9.4) | 9 (6.9) | 16 (11.9) | 1.5457 | 0.2138 | |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 20 (7.5) | 5 (3.8) | 15 (11.1) | 2.2405 | 0.1344 | |

| Diarrhoea | 9 (3.4) | 3 (2.3) | 6 (4.4) | 1.2638 | 0.2609 | |

| Constipation | 33 (12.4) | 10 (7.6) | 23 (17.0) | 1.2489 | 0.2638 | |

| Urination alterations | 4 (1.5) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.5) | 0.0241 | 0.8765 | |

| Polyuria/polydipsia | 22 (8.3) | 5 (3.8) | 17 (12.6) | 7.1148 | 0.0076 | |

| Orthostatic vertigo | 21 (7.9) | 8 (6.1) | 13 (9.6) | 1.1492 | 0.2837 | |

| Palpitations/tachycardia | 30 (11.3) | 10 (7.6) | 20 (14.8) | 2.6455 | 0.1038 | |

| Increased perspiration | 21 (7.9) | 5 (3.8) | 16 (11.9) | 7.119 | 0.0076 | |

| Others | ||||||

| Rash | ||||||

| Morbilliform | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | |

| Petechial | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | |

| Urticarial | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.5) | 0.0435 | 0.8348 | |

| Psoriatic | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0.8095 | 0.3683 | |

| Unclassifiable | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 1.3125 | 0.2519 | |

| Pruritus | 7 (2.6) | 2 (1.5) | 5 (3.7) | 1.6202 | 0.2031 | |

| Photosensitivity | 6 (2.3) | 1 (0.8) | 5 (3.7) | 1.3892 | 0.2385 | |

| Increased pigmentation | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 0.4444 | 0.505 | |

| Weight gain | 37 (13.9) | 18 (3.7) | 19 (14.1) | 0.4174 | 0.5183 | |

| Weight loss | 8 (3.0) | 3 (2.3) | 5 (3.7) | 0.1356 | 0.7127 | |

| Menorrhagia | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.5) | 2.3731 | 0.1234 | |

| Amenorrhea | 8 (3.0) | 3 (2.3) | 5 (3.7) | 0.1495 | 0.699 | |

| Galactorrhea | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 0.8235 | 0.3642 | |

| Gynaecomastia | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.2) | 3.0699 | 0.0798 | |

| Increased sexual desire | 8 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 8 (5.9) | 6.3486 | 0.0117 | |

| Decreased sexual desire | 8 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 8 (5.9) | 7.7773 | 0.0053 | |

| Erectile dysfunction | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | |

| Ejaculatory dysfunction | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.5) | 0.3496 | 0.5543 | |

| Orgasmic dysfunction | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 0.8981 | 0.3433 | |

| Vaginal lubrication | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 1.5 | 0.2207 | |

| Headaches | ||||||

| Tension | 33 (12.4) | 8 (6.1) | 25 (18.5) | 4.1967 | 0.0405 | |

| Migrainous | 7 (2.6) | 2 (1.5) | 5 (3.7) | 1.0757 | 0.2997 | |

| Other forms | 6 (2.3) | 1 (0.8) | 5 (3.7) | 02/01/1900 | 0.1365 | |

| Physical dependence | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | |

| Psychological dependence | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.7) | 0.0076 | 0.9305 | |

CMH: Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel; NA: not applicable; naïve: patients who had not taken any antipsychotic drugs before being included in the study; P: significance<0.05; quasi-naïve: patients who had taken antipsychotics for a period of less than 30 days before being included in the study.

Figures in bold indicate that the difference is statistically significant.

We found statistically significant differences in favour of a greater number of quasi-naïve patients in the following symptoms: in the psychological area, anxiety/laxity/fatigability, somnolence/sedation, increase in the duration of sleep, increased sleeping and emotional indifference; in the neurological area, hypokinesia/akinesia and paresthesias; in the autonomic area, accommodation disorders, increased salivation, polyuria/polydipsia and increased perspiration; and, finally, in the area others, increased sexual desire, decreased sexual desire and tension headaches.

Assessment of involuntary movementsTable 5 shows the baseline results on the MPRC-IMS scale for all the patients who obtained at least a score of slight for the symptoms assessed. The results are presented both considering the entire sample assessed and considering the scores obtained by the 2 groups that constituted the sample (naïve and quasi-naïve patients), controlling the latter by the baseline diagnosis.

Baseline scores for the MPRC-IMS (Maryland Psychiatry Research Center Involuntary Movement Scale).

| Total sampleNo. (%) | Naïve patientsNo. (%) | Quasi-naïve patientsNo. (%) | CMH | P | |

| Dyskinesia | |||||

| Spastic tongue movements | 95 (35.7) | 26 (19.8) | 69 (51.1) | 21.421 | <0.0001 |

| Kissing/sucking movements, pulling faces | 14 (5.4) | 5 (3.8) | 9 (6.7) | 0.968 | 0.3253 |

| “Tick-like” movements in the eyes and periorbital region | 13 (4.9) | 8 (6.1) | 5 (3.7) | 0.193 | 0.6606 |

| Gesticulation (irregular, lateral movements in cheeks and centrofacial region) | 21 (7.9) | 9 (6.9) | 12 (8.9) | 0.626 | 0.4288 |

| Spastic, irregular movements, with finger extension and flexion | 59 (22.2) | 59 (22.2) | 44 (32.6) | 13.751 | <0.001 |

| Habitual shaking of arms and elbows | 6 (2.3) | 3 (2.3) | 3 (2.2) | 0.064 | 0.7998 |

| Spastic contractions and spastic movements of arms and elbows | 44 (16. | 13 (9.9) | 31 (23.0) | 6.015 | 0.0142 |

| Spastic movements of neck, shoulders and head, shrugging shoulders | 12 (4.5) | 7 (5.3) | 5 (3.7) | 1.163 | 0.2809 |

| Alternating knee movements | 15 (5.6) | 5 (3.8) | 10 (7.4) | 1.242 | 0.265 |

| Spastic movements in ankles, foot tendons and toes | 11 (4.1) | 6 (4.6) | 5 (3.7) | 0.162 | 0.6877 |

| Exaggerated rocking, arms hanging, hypotonic or flaccid | 10 (3.8) | 4 (3.1) | 6 (4.4) | 0.314 | 0.5754 |

| Stomping gait | 11 (4.1) | 2 (1.5) | 9 (6.7) | 2.019 | 0.1553 |

| Rapid forward pelvic projections | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 0.824 | 0.3642 |

| Involuntary diaphragm movements and/or guttural sounds | 3 (1.1) | 3 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 3.836 | 0.0502 |

| Parkinsonism | |||||

| Habitual tongue tremor | 30 (11.3) | 12 (9.2) | 18 (13.3) | 0.792 | 0.3735 |

| Salivation | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.5) | 2.275 | 0.1315 |

| Habitual lip tremor | 3 (1.1) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | 1.079 | 0.2989 |

| Habitual tremor of the eyes and periorbital region | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

| Loss of eye blinking | 7 (2.6) | 4 (3.1) | 3 (2.2) | 0.013 | 0.9091 |

| Rigid “mask” facial expression | 21 (7.9) | 6 (4.6) | 15 (11.1) | 3.887 | 0.0487 |

| Jaw tremor | 4 (1.5) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.5) | 0.013 | 0.9106 |

| “Money-counting” tremor | 7 (2.6) | 4 (3.1) | 3 (2.2) | 0.379 | 0.5384 |

| Customary resting finger tremor | 46 (17.3) | 21 (16.0) | 25 (18.5) | 0.732 | 0.3921 |

| Muscle rigidity in arms and elbows | 10 (3.8) | 5 (3.8) | 5 (3.7) | 0.287 | 0.5925 |

| Muscle rigidity in legs and feet | 8 (3.0) | 2 (1.5) | 6 (4.4) | 2.139 | 0.1436 |

| Customary leg and foot tremor | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.5) | 2.532 | 0.1116 |

| Decreased rocking with stiff arms | 36 (13.5) | 9 (6.9 | 27 (20.0) | 6.295 | 0.0121 |

| Rigid, foot dragging gait | 13 (4.9) | 1 (0.8)) | 12 (8.9) | 6.465 | 0.011 |

| Assessment | |||||

| Overall | |||||

| Dyskinesia | 110 (41.4) | 40 (30.5) | 70 (51.9) | 9.509 | 0.002 |

| Parkinsonism | 74 (27.8) | 24 (18.3) | 50 (37.0) | 12.498 | 0.0004 |

| Akathisia | 10 (3.8) | 1 (0.8) | 9 (6.7) | 4.070 | 0.0437 |

CMH: Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel; NA: not applicable; naïve: patients who had not taken any antipsychotic drugs before being included in the study; P: significance<0.05; quasi-naïve: patients who had taken antipsychotics for a period of less than 30 days before being included in the study.

Figures in bold indicate that the difference is statistically significant.

Among the 3 areas assessed, in the case of dyskinesia, statistically significant differences in favour of a greater number of quasi-naïve patients were found in the following symptoms: spasmodic tongue movements, irregular spasmodic movements, with finger extension and flexion, and spasmodic arm and elbow contractions and movements; in parkinsonism, rigid “mask” facial expression, decreased rocking with stiff arms and rigid gait dragging the feet.

In the overall assessments of dyskinesia, parkinsonism and akathisia, a statistically significant greater number of quasi-naïve patients were likewise observed with these symptoms.

DiscussionThis article describes the design and baseline results of a study carried out in 4 Spanish hospitals with children and adolescents for which a first or second generation [atypical] antipsychotics was prescribed. We present the follow-up protocol throughout 12 months of treatment, assessing the safety and tolerance of using these drugs in a child–adolescent population. Likewise, we present the assessment tools used.

From the total quasi-naïve patients, 98.4% were prescribed SGA (risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine or aripiprazole) and only 7 patients were prescribed a FGA (haloperidol, pimozide or chlorpromazine). These data are in keeping with studies on the prevalence of antipsychotics use in children and adolescents, studies that describe the significant increase that has been produced in SGA prescriptions to the detriment of FGA.2From the quasi-naïve patients, only 1.9% were receiving combined antipsychotic treatment; this is a very low percent compared with what normally occurs in the adult population, in which polypharmacy is a general practice (especially in the United States) despite the fact that what is recommended is antipsychotic monotherapy.33–35

Many studies mention the relationship between antipsychotic dose and the appearance of side effects, an aspect also observed regularly in clinical practice. In spite of this, the data that exist up to now provide contradictory results.36–38 Our detailed record-keeping for the drugs, as well as the lengthy 12-month patient follow-up, will make it possible for us to analyse this and to attempt to provide clarifying data.

The patients included in the study had prescriptions for, along with the antipsychotics, other psychotropic drugs (benzodiazepines, antidepressants, mood stabilisers [lithium and antiepileptics] and stimulants); this should be remembered when attributing the appearance of side effects to the action of the antipsychotics or to third-line drugs.39 An example of this is a previous study by our team16 that found a possible protective effect of antidepressants in SGA weight increase.

The areas in which the greatest number of patients presented symptoms when the side effects were analysed using the UKU scale were the psychological, neurological and autonomic areas. A subanalysis differentiating between naïve and quasi-naïve patients revealed a significantly greater number of the latter with these symptoms. In assessing extrapyramidal symptoms, we found similar results, with statistical significance for the greater number of quasi-naïve patients who presented symptoms of dyskinesia, parkinsonism and akathisia. The length of the studies carried out up to now has not been more than 12 weeks40; consequently, this study will also let us see possible changes as well as the development of the extrapyramidal symptoms over longer periods of time. These results obtained at baseline level show that in child–adolescent populations both the appearance of side effects and of extrapyramidal symptoms are already observed from the start of antipsychotic exposure.

Our results should be interpreted bearing in mind a series of limitations. In the first place, the study was carried out in hospital centres, so 72.9% of the sample consisted of patients with hospital admission. This skews the severity of the pathology and includes a bias when attempting to generalise the results obtained with those from other, out-patient samples. In the second place, despite the fact that we measured treatment adherence using objective techniques, this analysis could not be performed in the entire sample because not all of the centres had the techniques available. In the third place, measurements of the severity of the illness were not included; these would have made it possible to assess the efficacy balance between efficacy and side effects. Such measurements should be considered in future studies.

Among the strong points of our study, we can highlight the following: firstly, as far as we know this is the first study with naïve or quasi-naïve children and adolescents, with such a large sample size, in which they have had 12 months of follow-up on antipsychotic treatment, assessing clinical and biological variables to enable early detection of the possible appearance of side effects. Secondly, practically half of the sample consisted of children and adolescents that had never received antipsychotic treatment and the rest had minimal exposure. Thirdly, this study will make it possible to assess directly in child–adolescent populations the safety and tolerance of these drugs. Based on the results obtained in adults, it is impossible to infer their safety and tolerance in individuals still in their growth period; an example of this is the studies showing that the side effects of the SGA are more evident in children than in adults.41–43 In fourth place, one of the interests of clinicians is to establish the differential profile of the antipsychotics. With respect to side effects, the antipsychotics present very heterogeneous profiles, for example, that the weight increase differs from some SGA to others.19 This study will make it possible to provide information on the differential and longitudinal behaviour of the antipsychotics, especially of the SGA. Finally, this study is in agreement with the laws of the FDA (US Food and Drug Administration) and the EMA (European Medicines Agency) – which require studies designed for children and adolescents–that enable the confirmation of the use of these drugs, providing more information on their safety and tolerance in this population.

The main objective of this article was to present a protocol designed to enable early detection of severe side effects from the use of antipsychotic drugs in the child–adolescent population. After the results that are obtained and once their usefulness has been demonstrated, we hope that they facilitate the development and implementation in standard clinical practice of specific follow-up protocols for children and adolescents with antipsychotic treatment.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that the procedures followed conformed to the ethical standards of the human experimentation committee in charge and were in agreement with the World Medical Organisation and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their work centres about the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained informed consent from the patients and/or subjects included in the article. This document is filed with the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank the Centre of Biomedical Research in the Mental Health Network (CIBERSAM), Madrid (Spain); for partial funding, the following: the Spanish Ministry of Health, Instituto de Salud Carlos III «Health Research Fund» (F.I.S.-PI04/0455); Madrid Mental Health Association («Miguel Angel Martín» Research Grant); «NARSAD 2005: Independent Investigator Award»; Alicia Koplowitz and Mutua Madrileña foundations; and the Ministries of Science and Innovation, Community of Madrid, Biomedical R&D funding S2010/BMD-2422 AGES (Madrid) for their support.

Please cite this article as: Merchán-Naranjo J, et al. Efectos secundarios del tratamiento antipsicótico en niños y adolescentes naïve o quasi-naïve: diseño de un protocolo de seguimiento y resultados basales. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2012;5:217–28.