To date, there is a relative dearth of measures focusing on social anhedonia that are suitable for both patient and non-patient samples, up to date in terms of their content, and relatively brief. The goal of the present investigation was to validate the Spanish translation of the Anticipatory and Consummatory Interpersonal Pleasure Scale (ACIPS)-adult version for use with Spanish-speaking population.

MethodThe total sample included 387 nonclinical individuals from Spain (128 males). The mean age was 21.86 (SD=5.11; range 18–46 years). The ACIPS and the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) were used.

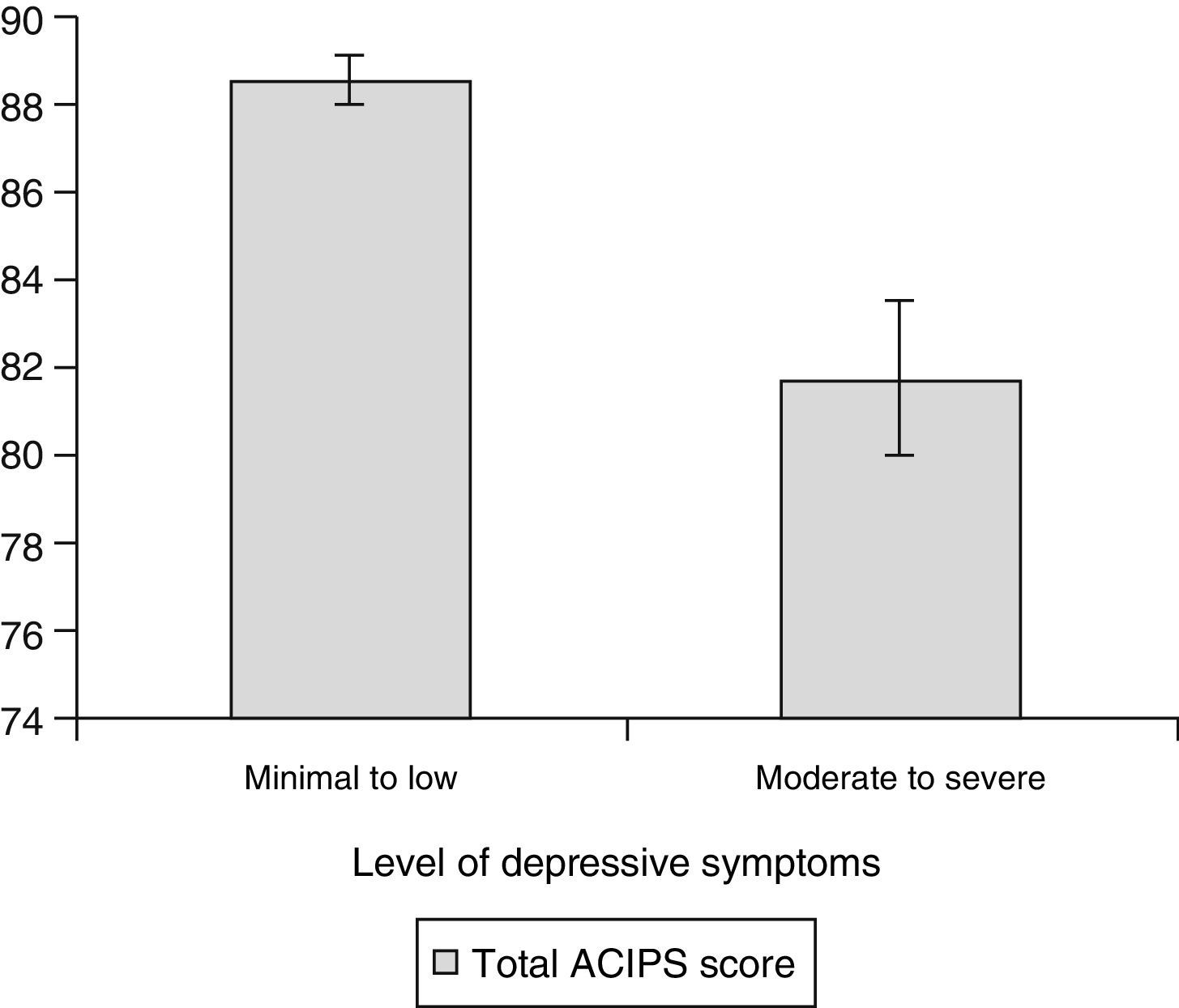

ResultsExploratory factor analysis yielded a three-factor solution which explained 79.1% of the variance (Intimate Social Interactions, social bonding in the context of media/communications, and casual socialization). The total ACIPS showed good internal consistency, estimated with ordinal alpha was 0.92, ranging from 0.76 to 0.84 for the subscales. The participants who reported a minimal to low level of depressive symptoms had significantly higher total ACIPS scores than the participants who reported experiencing moderate to severe levels of depressive symptoms. Total scores on the ACIPS were negatively associated with scores on the BDI-II (r=−0.22, p<0.001). Participants with a family history reported significantly lower total ACIPS scores than those without a family history of schizophrenia.

ConclusionsThe present results showed that the Spanish version of the ACIPS scores had adequate psychometric properties. The ACIPS may be useful in terms of helping to elucidate the ways in which individual differences in hedonic capacity for social and interpersonal relationships relates meaningfully to risk for various forms of psychopathology.

Hasta la fecha hay una relativa escasez de medidas centradas en la evaluación de la anhedonia social que sean útiles para su uso tanto en pacientes como en población general, y que al mismo tiempo sean adecuadas en cuanto a su contenido y brevedad. El objetivo de la presente investigación fue validar la traducción española de la Escala de Placer Interpersonal Anticipatorio y Consumatorio (ACIPS)-versión para adultos.

Métodola muestra total incluyó 387 participantes no clínicos (128 hombres). La media de edad fue de 21,86 (SD=5,11; rango 18–46 años). Se utilizaron la ACIPS y el Inventario de Depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II) como instrumentos de medida.

Resultadosel análisis factorial exploratorio arrojó una solución de tres factores que explicó el 79,1% de la varianza total (Interacciones sociales íntimas, vinculación social en el contexto de los medios de comunicación y la socialización informal). El alfa ordinal para la puntuación total de la ACIPS fue 0,92, oscilando entre 0,76 y 0,84 para las subescalas. Los participantes que informaron de bajos niveles de síntomas depresivos tenían significativamente mayores puntuaciones en la ACIPS en comparación con aquellos que presentaban niveles moderados-graves. La puntuación total de la ACIPS se asoció negativamente con las puntuaciones del BDI-II (r=−0,22, p<0,001). Los participantes con historia familiar previa de esquizofrenia mostraron puntuaciones significativamente más bajas en la ACIPS comparativamente con aquellos que no tenían antecedentes familiares.

ConclusionesLos resultados parecen mostrar que la versión española de la ACIPS presenta propiedades psicométricas adecuadas. La ACIPS podría ser una herramienta útil para analizar las diferentes formas en que las diferencias individuales en la capacidad hedónica de las relaciones interpersonales se relacionan con el riesgo de padecer psicopatología.

Despite the generally rewarding nature of social relationships, hedonic capacity for interpersonal interactions is continuously distributed throughout the general healthy population. That is, although most of the population enjoys interacting with others, there is a smaller group of nonclinical individuals who do not derive pleasure from social interactions. In this way, social anhedonia, the reduced experience of pleasure from social and interpersonal interactions, can be considered to exist on a continuum.1–3 Social anhedonia is a common symptom in a variety of psychiatric disorders, including major depression, schizophrenia and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, autism, and eating disorders. Individuals with major depressive disorder frequently experience state-related social anhedonia.4 However, previous research indicates that the social anhedonia that often characterizes schizophrenia and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders is stable and trait-like in nature.4,5 Therefore, it is important and useful to have appropriate scales to assess the entire continuum of social anhedonia, i.e., from the levels that might be observed in nonclinical populations to the levels observed across various forms of psychopathology.2

To date, there is a relative dearth of measures focusing on social anhedonia that are suitable for both patient and non-patient samples, up to date in terms of their content, and relatively brief. The Anticipatory and Consummatory Interpersonal Pleasure Scale (ACIPS)6,7 satisfies all the aforementioned criteria. The ACIPS has considerable clinical utility. First, it provides an indirect measure of social anhedonia, which in its extreme form, has been observed in various clinical disorders including depression, schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, and autism spectrum disorders.1 ACIPS scores distinguish between psychiatric and nonpsychiatric patient groups, with the latter showing significantly higher scores.8 One further advantage of the ACIPS is that it is applicable to both clinical and nonclinical populations, thereby allowing a dimensional perspective and thus being consistent with a Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) perspective.9

Originally developed as an indirect measure of social anhedonia, the ACIPS scores have sound psychometric properties. For example, across different U.S. contexts, involving a variety of samples such as college undergraduates, community volunteers, and outpatients with and without psychotic symptoms, the ACIPS has shown high internal consistency. Moreover, total ACIPS scores have been negatively associated with social anhedonia and social withdrawal, and positively associated with measures of social connectedness, anticipatory and consummatory pleasure, and prosocial rewards.7,10–12 More recently, an investigation of the Chinese translation of the ACIPS13 revealed that the measure shows high internal consistency and convergent validity in nonclinical Chinese adults. Taken together, findings to date suggest that the ACIPS is a promising and valid tool for use in measuring individual differences in the experience of, and capacity for, social and interpersonal pleasure.

There are very few instruments to assess anhedonia available for use in Spanish-speaking populations.14 The Chapman anhedonia scales, namely, the revised Social Anhedonia Scale (RSAS)15 and the revised Physical Anhedonia Scale (RPAS)16 are available in Spanish, though they have been criticized for being somewhat lengthy and possibly outdated. Moreover, they are not designed to be used with samples under the age of 18. The Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale (TEPS)17 has been recently been made available in Spanish.18 However, the TEPS is not specifically focused on assessing social anhedonia, so the ACIPS fulfills a clinical and research niche. Moreover, developmentally-appropriate versions of the measure have been developed for use in healthy and high-risk adolescents (e.g., ACIPS-adolescent version) and children (e.g., ACIPS-child version).

The goal of the present investigation is to validate the Spanish translation of the ACIPS for use with Spanish-speaking populations. We hypothesized that the ACIPS would perform similarly in the Spanish culture as it does in the American culture, i.e., show a three- or four-factor structure. We also expected to observe a gender difference in terms of self-reported social and interpersonal pleasure. A secondary goal of this study was to examine the relationship between ACIPS scores and scores on a well-validated measure of depressive symptoms. We were particularly interested in exploring the usefulness of the ACIPS as a means to elucidate the ways in which these individual differences in hedonic capacity for social and interpersonal relationships relate meaningfully to risk for various forms of psychopathology. In order to do so, it is imperative that we examine the association between scores on the ACIPS and measures of clinical and subclinical symptomatology. Thus far, it appears that the ACIPS is sensitive to variations in levels of schizotypal traits. In both Western (U.S.) and Chinese nonclinical adult samples, ACIPS total scores are inversely associated with scores on the No Close Friends subscale of the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SPQ)19 and/or the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire-Brief Revised (SPQ-BR).20 These findings are consistent with prior research21,22–24 that suggests an association between schizotypal traits and social anhedonia. To date, the association between depressive symptoms and social anhedonia, as measured by the ACIPS, has not been explored. We were therefore particularly interested in examining the relationship between depressive symptomatology and capacity for social and interpersonal pleasure in a nonclinical sample of adults. Because anhedonia is often observed among depressive patients, we expected to see a relationship between ACIPS scores and BDI-II scores. A final goal was to examine whether individuals with a family history of schizophrenia would differ from those without a family history in terms of their reported enjoyment of social and interpersonal interactions. Given prior findings of an association between schizotypal traits and social anhedonia,1–3 we predicted that individuals with a family history of schizophrenia would be more likely to have schizotypal traits and thus also be more likely to differ in terms of their scores of social and interpersonal pleasure.

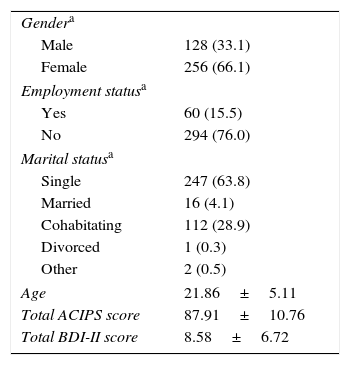

Materials and methodsParticipantsThe total sample included 387 nonclinical individuals from Spain. All the participants were enrolled in Bachelor's and Master's degree-level classes at the University of La Rioja, Department of Educational Sciences. Of them, 128 were men (33%) and nearly all of the others were women; three participants did not indicate their gender. The ages ranged from 18 to 46 years; the mean age was 21.86±5.11. Exclusion criteria included: age less than 18; IQ less than 70; and a personal history of psychosis or neurological disorder such as multiple sclerosis. Demographic statistics for the sample are provided in Table 1.

Demographic description of sample (n=387).

The Anticipatory and Consummatory Interpersonal Pleasure Scale (ACIPS) Adult version6,7 is a 17-item self-report measure that assesses individual differences in capacity to enjoy interpersonal interactions. Hedonic capacity for social and interpersonal engagement is rated on a 6-point Likert scale of 1–6, where 1=“very false for me” and 6=”very true for me”. Lower total scores reflect greater likelihood of social anhedonia.

Translation of the ACIPS was performed using the back translation procedure in accordance with international guidelines for translation of psychological measures.25,26 The (U.S.) English original version of the ACIPS6,7 was translated into Spanish by an expert in the subject matter. Subsequently, this version was translated into English by another bilingual researcher who was familiar with (American) English culture. Finally, a third researcher compared the two English versions (original and translated). The final Spanish version of the ACIPS that was used is presented in Appendix. Total scores on the ACIPS could vary from 17 to 102, with lower scores indicating greater likelihood of social anhedonia.

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)27 is a 21-item self-report instrument designed to assess the presence and severity of depressive symptoms. For each of the items, respondents must select more of the four statements, arranged in increasing severity (ranging from 0 to 3), that best describes their experience of the depressive symptom over the preceding 2 weeks. This measure is considered to have generally robust psychometric characteristics.28 We used the Spanish version of the BDI-II.29,30 Total scores on the BDI-II could vary from 0 to 63; increasing scores on the BDI-II indicate increasing levels of depressive symptomatology.

ProcedureQuestionnaires were administered in a group setting under psychologist supervision. Demographic information was obtained, including a question about participants’ family history (i.e., “Does anyone in your immediate family have schizophrenia?”). The students were not offered any incentives for participating in the study. After the goals of study were explained to them, individuals signaled their consent to participate by remaining in the classroom. Confidentiality was guaranteed by assigning participants a numeric code known only by the principal investigator. This research was approved by the ethics committee of the Department of Educational Sciences of University of La Rioja as well as the Education and Social/Behavioral Science Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Data analysesFirst, we calculated descriptive statistics for the distributions of gender, age, marital status, ACIPS, and BDI-II scores. We explored the relationship between age and ACIPS scores using Pearson correlations. We examined the ACIPS data for evidence of gender differences using the t-test for independent samples. In the case of significant findings, we computed Cohen's d to provide an estimate of the effect size of the difference. We then conducted an exploratory factor analysis on the ACIPS items in order to explore its factor structure. The method for factor extraction was Minimum Rank Factor Analysis; polychoric correlation matrix was used. We examined the internal consistency for the total ACIPS using reliability analysis, calculating the ordinal alpha coefficient based on the polychoric correlation matrix. We examined the relationship between the BDI-II and the ACIPS using Pearson correlations. Differences in total ACIPS scores between participants with and without a family history of schizophrenia were investigated using the Mann–Whitney U-test for independent samples. SPSS Version 2231 and FACTOR 9.232 were used for the analyses.

ResultsDemographic variablesNearly all of the participants (353 of 387, or 91%) reported being of Spanish origin. As indicated in Table 1, this was a generally young sample of students, who were largely unmarried full-time students, i.e. unemployed. There was no significant relationship between age and total ACIPS scores, r=−0.06, n.s. However, we noted significant gender difference, whereby females reported higher overall ACIPS scores than males, t (195)=5.27, p<0.001, d=0.60.

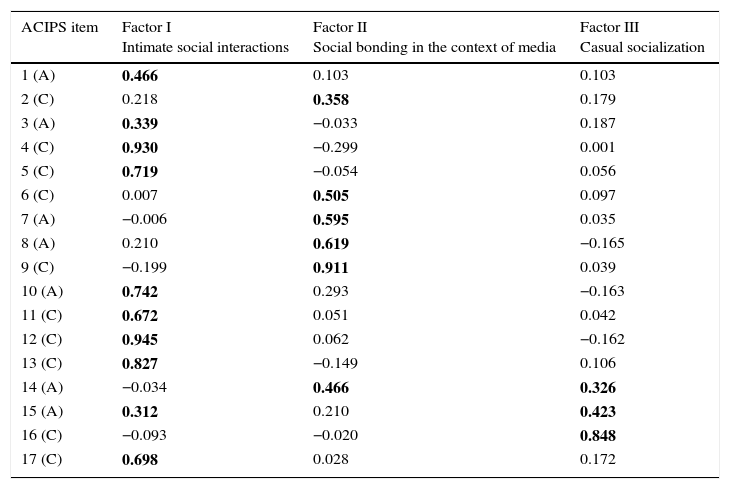

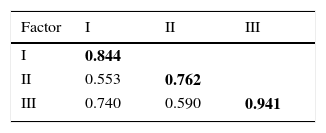

Factor structure of the Spanish translation of the ACIPSParallel analysis33 based on minimum rank factor analysis using polychoric correlation matrices yielded a three-factor solution, which explained 79.1% of the variance. All three factors assessed both anticipatory and consummatory aspects of pleasure (see Table 2). Eight of the seventeen items loaded onto the first factor (Intimate Social Interactions), which accounted for 44.2% of the common variance. The second factor, social bonding in the context of media/communications, accounted for 22.5% of the common variance. The third factor, casual socialization, accounted for 12.3% of the total common variance. Table 3 provides the intercorrelations between each of the factors.

Factor structure and estimated factor loadings of the ACIPS.

| ACIPS item | Factor I Intimate social interactions | Factor II Social bonding in the context of media | Factor III Casual socialization |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (A) | 0.466 | 0.103 | 0.103 |

| 2 (C) | 0.218 | 0.358 | 0.179 |

| 3 (A) | 0.339 | −0.033 | 0.187 |

| 4 (C) | 0.930 | −0.299 | 0.001 |

| 5 (C) | 0.719 | −0.054 | 0.056 |

| 6 (C) | 0.007 | 0.505 | 0.097 |

| 7 (A) | −0.006 | 0.595 | 0.035 |

| 8 (A) | 0.210 | 0.619 | −0.165 |

| 9 (C) | −0.199 | 0.911 | 0.039 |

| 10 (A) | 0.742 | 0.293 | −0.163 |

| 11 (C) | 0.672 | 0.051 | 0.042 |

| 12 (C) | 0.945 | 0.062 | −0.162 |

| 13 (C) | 0.827 | −0.149 | 0.106 |

| 14 (A) | −0.034 | 0.466 | 0.326 |

| 15 (A) | 0.312 | 0.210 | 0.423 |

| 16 (C) | −0.093 | −0.020 | 0.848 |

| 17 (C) | 0.698 | 0.028 | 0.172 |

Note: Rotated component matrix for the Spanish translation of the adult ACIPS. Parallel analysis with minimum rank factor extraction and weighted varimax rotation; variance explained=79.1%. In bold there are specified the articles that loaded in every factor.

The total ACIPS showed good internal consistency, with ordinal alpha=0.92. The internal consistency estimates for each of the ACIPS factors are provided on the diagonal in Table 3. The anticipatory pleasure items were correlated with the consummatory pleasure items on the ACIPS (r=0.77, p<0.05).

Relationship between social/interpersonal pleasure and depressive symptomsCorrelation analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between hedonic capacity for social and interpersonal interactions, as measured by the ACIPS, and presence of depressive symptoms, as measured by the BDI-II. Table 1 provides the means and standard deviations for the ACIPS and the BDI-II total scores. Total scores on the ACIPS were negatively associated with scores on the BDI-II, r=−0.22 (p<0.001).

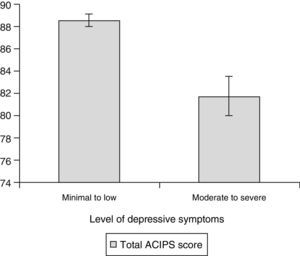

Approximately 91% (354 of 387) of the participants scored below the cutoff score for a moderate level of depression on the Spanish adaptation of the BDI-II (i.e., below a total score of 19). We compared the participants who reported a moderate or severe level of depressive symptoms to the remainder of the sample in terms of their total ACIPS scores. The participants who reported a minimal to low level of depressive symptoms had significantly higher total ACIPS scores than the participants who reported experiencing moderate to severe levels of depressive symptoms, t (385)=3.50, p<0.01, Cohen's d=0.65. Fig. 1 depicts the mean difference in total ACIPS scores.

The effect of family history of schizophreniaStudy participants were asked whether they had a family history of schizophrenia. Relatively few participants (n=5, 1.3%) reported a family history of schizophrenia, and nearly 5% of the sample (n=16) opted not to respond. We compared the participants with and without a family history of schizophrenia in terms of their social/interpersonal pleasure, as measured by the ACIPS. Participants with a family history reported significantly lower total ACIPS scores (M=70.80±27.8) than those without a family history of schizophrenia (M=88.13±10.35), one-sided p=0.023, r=0.10.

DiscussionThe main purpose of this study was to validate the Spanish translation of the adult version of the ACIPS for use with Spanish-speaking populations. We identified three factors via exploratory factor analysis, namely, “intimate social interactions”, “social bonding”, and “casual socialization”. The three factors we observed correspond to three different levels of social connectedness, ranging from relatively intimate to more casual, which is consistent with prior findings based upon U.S. samples.7,10–12 As expected, we found a gender difference in terms of self-reported social and interpersonal pleasure, whereby women had higher total ACIPS scores than the men. This gender difference in hedonic capacity was previously observed among U.S. college populations,7,10–12 community-derived adults,12 and nonclinical Chinese adults.13

The present results showed that the Spanish version of the ACIPS had good reliability, consistent with what was observed with the English (U.S.) version of the ACIPS. We also explored ways in which individual differences in hedonic capacity for social and interpersonal relationships related meaningfully to risk for depression by examining the association between total ACIPS scores and level of depressive symptomatology. We found evidence for a small but significant negative association between ACIPS scores and BDI-II scores, whereby individuals with higher BDI-II scores were more likely to have lower total ACIPS scores. Indeed, when we divided our sample according to their BDI-II scores, individuals with minimal levels of depressive symptoms reported significantly greater enjoyment of social and interpersonal interactions than individuals with moderate to severe levels of depressive symptoms.

The present study is characterized by several strengths. First, we included the Spanish translation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II, a well-validated measure of depression, and used culturally-based norms.30 However, one of the limitations of the present study is restriction of range. Relatively few of the individuals in our sample reported experiencing a moderate or severe level of depressive symptoms at the 2-week period that they were participating in the study. Future research would be enhanced by inclusion of a group of patients with depression, in order to further explore the association between social and interpersonal pleasure, as measured by the ACIPS, and depressive symptoms. It would be especially intriguing to include a group of healthy individuals with a past history of depression, compared to a group of depressed patients and a healthy comparison group.

Another strength of the present study is the fact that we queried the participants about their family history of schizophrenia. This enabled us to explore ways in which individual differences in hedonic capacity for social and interpersonal relationships related meaningfully to risk for schizophrenia. Specifically, we accomplished this goal by comparing the total ACIPS scores of participants with versus without a family history of schizophrenia. Given the small number of participants with a family history of schizophrenia, this aspect of our investigation was exploratory in nature. Nonetheless, we observed that the family history positive group reported significantly less enjoyment of social and interpersonal interaction than the rest of the sample, who did not have a family history of schizophrenia. These findings, albeit preliminary, are consistent with prior research11 that indicates an association between schizotypal traits and lowered enjoyment of social and interpersonal interactions, as measured by the ACIPS.

A limitation of the current study is that the study was not population-based. The findings were obtained from a convenience sample recruited from a university with a high percentage of female participants. As such, our results may not generalize to all young adults in the general Spanish population. It would be advisable to replicate these findings with a community-derived sample to determine their external validity. Another limitation of the present investigation is that participants were not screened for current emotional distress or past or present treatment of psychopathology. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that psychopathology may have influenced some of the participants’ responses. Furthermore, we relied entirely upon self-report methodology. This study would have been strengthened by the inclusion of corroborative information, such as diagnostic interviewing. Similarly, it might have been helpful to include an infrequency scale, to rule out random responding. However, we do not think that random responding or acquiescence bias was a major problem in this investigation, given prior findings that the ACIPS is relatively unaffected by social desirability bias.12

Despite these limitations, this study demonstrates that the Spanish version of the adult ACIPS is suitable for assessment purposes in Spanish-speaking settings. The ACIPS can measure a construct that overlaps with but is independent from depressive symptomatology. Through its unique focus on the characterization of social and interpersonal pleasure, the ACIPS may be useful in terms of helping to elucidate the ways in which individual differences in hedonic capacity for social and interpersonal relationships relates meaningfully to risk for various forms of psychopathology. Future studies need to replicate these findings in new clinical and nonclinical samples in Spanish populations. Research would also be enhanced by studying the relationship between social anhedonia and social cognition, negative symptoms, and/or drug abuse. This line of research would be further enriched by inclusion of other methodologies such as brain imaging techniques.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Lee cada afirmación cuidadosamente y decide qué grado de verdad tienen para ti en general. En el caso de que nunca hayas tenido la experiencia descrita, piensa en la experiencia más parecida que hayas tenido y marque la opción que más se aproxime. No te preocupes acerca de ser totalmente coherente en todas tus respuestas. Elije entre las siguientes seis opciones de respuesta e indique su respuesta en el espacio a la derecha de cada ítem.

1=Totalmente falsa para mí; 2=Moderadamente falsa para mí; 3=Ligeramente falsa para mí; 4=Ligeramente verdadera para mí; 5=Moderadamente verdadera para mí; 6=Totalmente verdadera para mí.

Por favor responde a todas las afirmaciones. Muchas gracias por tu colaboración.

| 1. Estoy deseando ver a la gente cuando voy de camino a una fiesta o a quedar con otras personas. |

| 2. Disfruto mirando fotografías de mis amigos y familia. |

| 3. Realmente no me gustan las reuniones familiares o las tertulias (reuniones con otras personas). |

| 4. Disfruto bromeando y hablando con un amigo o un compañero de trabajo. |

| 5. Una buena comida siempre tiene mejor sabor cuando comes con un amigo cercano. |

| 6. Me gusta cuando la gente llama o manda mensajes de texto sólo para decir hola. |

| 7. Cuando algo bueno me pasa, no puedo esperar a compartirlo con otros. |

| 8. Si conociera un grupo donde las personas compartieran los mismos intereses que yo, estaría interesado en unirme a ellos. |

| 9. Disfruto viendo películas sobre la amistad o relaciones, con mis amigos. |

| 10. Me imagino que sería muy divertido ir de vacaciones con un amigo o alguien a quien amas. |

| 11. Valoro mucho cuando me invitan a quedar con gente que conozco después del colegio o del trabajo. |

| 12. Estoy feliz cuando veo un amigo o alguien a quien amo que no he visto en mucho un tiempo. |

| 13. Disfruto haciendo actividades grupales, como ir a eventos deportivos o conciertos con mis amigos. |

| 14. Me gusta ver mis programas favoritos de televisión con mis amigos. |

| 15. Me emociono cuando un amigo que no he visto en un tiempo me llama para hacer planes- |

| 16. Me gusta hablar con otros mientras espero en una fila. |

| 17. Disfruto cuando charlo con un amigo sobre cosas importantes. |

Please cite this article as: Gooding DC, Fonseca-Pedrero E, Pérez de Albéniz A, Ortuño-Sierra J, Paino M. Adaptación española de la versión para adultos de la Escala de Placer Interpersonal Anticipatorio y Consumatorio. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2016;9:70–77.